Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

Steven Universe Season 3 Episode 3: Same Old World

993 notes

·

View notes

Photo

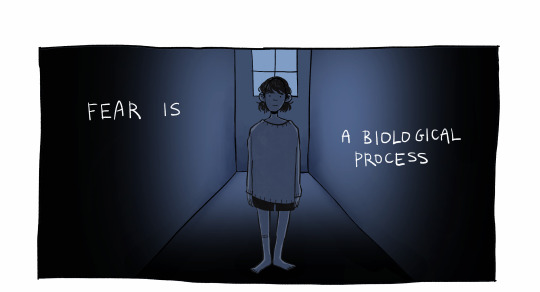

little comic for the digital salt and citrus zine vol 1.5, “fear”! i also drew the cover hehe you can see all that here (x)

(i also did a little interview if you want to read that too)

[id: a two-page comic in shades of blue and grey. the first page reads, broken up among the panels, “fear is a biological process designed to help us survive; to be safe.” the panels show a young girl at the end of a hallway, in front of a window. she is sweating profusely and her hands are shaking as she gazes at a door at the other end of the hall; below the door, a red glow can be seen.

the second page shows the young girl slowly approaching the door until she puts her ear against it, listening. she cups her hand around her mouth and whispers to the door, “should i be afraid?” hearing no response, she walks away from the door; the viewer sees, however, the narrative text that reads, “oh, darling. always,” and a ghastly figure creeping behind the door with sunken eyes and a gaping mouth, unseen by the girl. end id.]

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

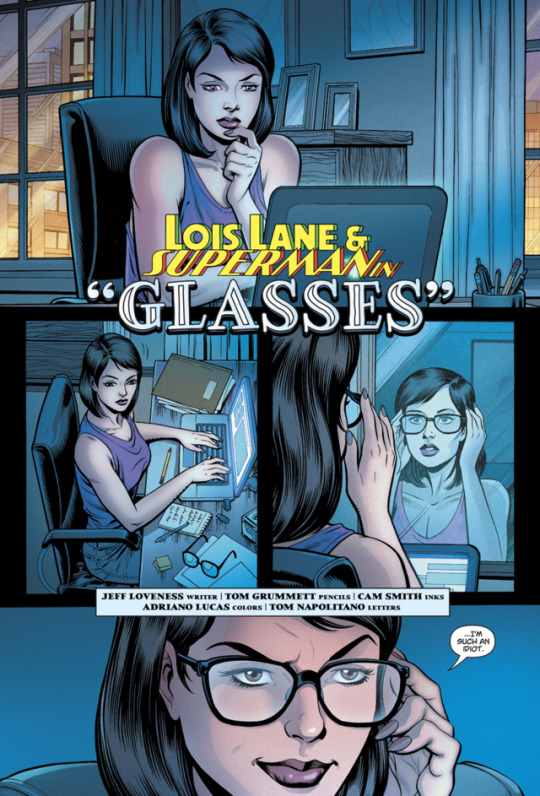

Mysteries of Love in Space #1 - “Glasses” (2019)

written by Jeff Loveness art by Tom Grummett & Cam Smith

73K notes

·

View notes

Photo

one of my grandparents’ kittens taking a nap inside a toy truck

137K notes

·

View notes

Text

Bonus Characters

You may have noticed during play that there is one window on each level that looks different to all the other windows. Let’s call it the special window.

This window is special for a couple of reasons. Firstly, if you take too long on a level a monster will appear in the special window and spit fireballs at you. Not good. Secondly, if you play well enough a bonus character will appear in the special window at the end of certain levels and award you with a massive point bonus. These bonuses are key to big scores.

Exactly when these characters appeared and why was a mystery. All manner of hypotheses were put forward, but nobody knew exactly what was happening. Until now.

Huge thanks to Phil Bennett of the MAME team for his expertise in reverse-engineering Flicky and exposing the finer details of how things work. Hip hip hooray!

A bonus character may appear at the end of rounds 10, 18, 26, 34, 42 and 50. Their presence is determined by your performance over the previous 7 rounds. On each round you must:

1) Save all 8 piopio at once. 2) Finish in under the following time limits:

Rounds Time Limit (seconds) 4-10 30 12-18 35 20-26 40 28-34 50 36-42 60 44-50 60

The points awarded for each character appearance are:

Round Bonus (points) Character 10 10,000 Girl (waving) 18 50,000 Pengo (dancing) 26 100,000 Female Flicky (dancing) 34 500,000 Rabbit (dancing) 42 1,000,000 Girl (winking) 50 1,000,000 Girl (waving)

Your performance during the so-called bonus rounds has no effect on the whether or not a bonus character appears.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Sega Arcade Revolution: A History in 62 Games

Flicky (September 1984)

Maze games were very popular during the first half of the 1980s. Hits like Pac-Man had made large sums of money for Sega’s rivals, and though the video arcade industry was no longer moving at the same speed it had during its early years, the genre was still popular enough that publishers kept up a steady rhythm of releases. Sega looked to its R&D division to come up with something that could keep pace with Namco and Bally/Midway. What it got was a little blue bird named Flicky.

Flicky’s development team was led by Youji Ishii, a Sega designer who would one day be responsible for the classic game Fantasy Zone. Having joined Sega in April 1978 after graduating with a degree in electrical engineering, Ishii was interested in creating games that were bright and colorful, and he believed that his works should be happy experiences for players. He started working on sound effects for games like Deep Scan and Zaxxon and got his first chance at design with 1983’s Up’n Down, a pseudo–3D arcade driving game. It sold enough for Sega to assign him to another title, one that was likely more important to Ishii’s career as it was to his employer’s bottom line. Sega meant for Flicky to be its response to Namco’s Mappy, emulating the time-based maze dynamic that was popular at the time. The visual style and gameplay Ishii had in mind would give Sega the competitor it wanted (Derboo, “Flicky”; “Fantasy Zone—2014”).

Flicky put players in the role of a blue sparrow who must rescue her chick friends, called Chirps (In Japan, they were called “Piopio,” a misspelling of the Japanese word “pyopyo” which means “baby bird”). The chicks had run amok inside an apartment building, and Flicky had to gather them all and guide them to the exit. Hungry cats called “Tiger” in the Western version and “Nyannyan” in Japanese actively chased the chicks, as did an iguana named Iggy (Choro in Japan). Touching the chicks put them in line behind Flicky, who had to avoid enemies while bringing all the chicks to the door. Items such as cups and trumpets were scattered throughout the stages, and Flicky could shoot these items at the cats and iguana to temporarily incapacitate them. The Nyannyan couldn’t hurt the baby birds, but they could kill Flicky with a single touch. The game lasted 48 stages before looping with a harder difficulty (Derboo, “Flicky”).

Ishii’s adorable character designs were brought to life by the talented hand of Yoshiki Kawasaki, a young artist who had joined the company because it was the closest job offer to his home. He had been a big fan of pinball and driving games, playing in the dark arcades of Hibiya, Japan, so the chance to join Sega was an exciting opportunity for him. Kawasaki was hired at Sega in 1976 as a designer. Though he was an artist, he started out in the purchasing department, and he spent many an hour playing Head-On. His work soon came to the attention of Hideki Sato, who recognized his talent and moved him over to the visual design division of Sega’s research and development department. His first assignment was the SG-1000 version of Golgo 13. After working on the laserdisc game Albegas and another release called Sinbad Mystery, Kawasaki began to long for something more interesting. He got his chance when he was handed the proposal for Flicky from the game’s lead designer. Kawasaki would finally have his big chance to put his programming abilities to greater use (“Interview: Yoshiki Kawasaki”).

When Kawasaki was assigned to Flicky, all that existed was a simple four-page proposal. There was to be a labyrinth and a simple game character. The concept was just a derivation of Namco’s Pac-Man, where players would collect dots in the maze. Ishii liked maze games, and he knew he wanted the game to follow that motif. He was certain of one thing: Flicky would not penalize players for falling through the floors as Mappy did. This was the starting design premise for the game and the reason why a bird was chosen as the main character (“Fantasy Zone—2014”). The problem was that nothing was detailed; there wasn’t even a description of the game’s background. The character profiles were also incredibly vague, reading “since the maze can be simple lines, the characters can look simple too. You can leave the background black.” Kawasaki based the main character, Flicky, on a lyric from a popular 1977 song called “Densen Ondo,” which referred to three sparrows on an electric line. Kawasaki wondered why birds would move on electric lines when they could simply fly. He figured that perhaps they jumped, so he decided to have Flicky jump (or “heroically jump,” as he put it) instead of fly. The Chirps were an evolution of the dots in the maze. Kawasaki revealed how he developed the little birds in an interview for Sega of Japan’s website:

The dots were originally really just dots. When you collected one it would disappear. But then, I thought it would be interesting if the dots didn’t disappear but instead line up. So, I made the dots line up behind Flicky. That’s when I really started fleshing things out. I asked if I could make the dots 8 × 8 pixels big, but in the end, I couldn’t do anything with 8 × 8 pixels. Then I thought: If they were little birds, I could do it [“Interview: Yoshiki Kawasaki”].

At first, he simply had the Chirps follow their bird friend back to the exit door. That was too simple, so he had them scatter when touched by a cat. When it proved too easy to gather up all the Chirps, Kawasaki spiced things up by having some of them race off in different directions. He gave these “Bad Chirps” sunglasses so that players would be able to recognize them (“Interview: Yoshiki Kawasaki”).

Creating those cute little chicks with attitude wasn’t very easy; none of the character models were. Kawasaki had to use a rudimentary tool that was similar to Sega’s TV Oekaki, a tablet-like device that came with a light pen. It plugged directly into televisions and was made available commercially for Sega’s SG-1000 in 1985. Using such a simple tool was problematic, particularly getting it to draw single pixels. It would often draw three or four at once (“Interview: Yoshiki Kawasaki”).

Kawasaki’s original level design had horizontal lines on the screen that resembled power lines. These lines were to act as the maze walls; however, once Flicky’s characters were completed, Kawasaki found the lines to be dull and unengaging. It was only after gazing out the window at an apartment building across the street from his third-floor window in Sega’s R&D annex building that Kawasaki found the perfect setting. Why not have the action take place in an apartment building? The residential setting let Kawasaki insert household items, like cups and baby bottles—things that would be found in a home with children. They would also help Flicky fight off Tiger and Iggy (“Interview: Yoshiki Kawasaki”).

Flicky played differently than most games of its type, most notably in the way the main character jumped. The control was very floaty and heavy with inertia. Players had to time their jumps correctly, particularly when coming down from the top of the screen. Ishii believed this was the product of the hardware limitations of the System 1 arcade board. These restrictions also influenced the design of the labyrinth stages, which did a decent job of creating the illusion of size. Ishii commented about this challenge in a 2014 interview with STG Gameside. “With Flicky, we challenged ourselves to make the stages feel like wide, expansive spaces despite the tiny memory available” (“Fantasy Zone–2014”).

Ishii was also able to make Flicky seem larger than it really was using free-scrolling stages. Players could move either left or right almost indefinitely, giving the stages a larger sense of scale. The inspiration for this design came from two sources: Williams Electronics’ 1981 smash Defender and a far-lesser known Commodore 64 title named Drol, which involved a flying and shooting robot. “Basically,” Ishii explained to Shooting Gameside in 2014, “I just like that style. I like how you can rush forward, then turn around really quick and retreat if you need to.” Ishii would revisit this design for his 1986 hit, Fantasy Zone (“Fantasy Zone—2014; Ishii).

The stages themselves weren’t random scenery. There was an overall theme to them that was very close to the team, particularly Kawasaki. As the gameplay centered on the concept of saving children, Kawasaki’s group wanted this objective to be Flicky’s driving theme. It wasn’t just about bringing some birds to a door for points; there was more to it than that. Kawasaki wanted players to feel the maternal instinct of protecting defenseless children from predators. He felt they could sympathize, even though the chicks were merely game characters on a screen. After all, Flicky was a sparrow, not a chicken, and while she was only the chicks’ friend and not their mother (despite being labeled as such in the SG-1000 port of the game) she could still want to protect them. “Children face a variety of dangers when they go outside,” he commented in a 2016 interview, “and the feeling of ‘wanting to return them safely to the nest’ is something that I think is experienced 80 The Sega Arcade Revolution by not just parents, but anyone who is around children. And it’s that emotion that drives Flicky, a sparrow, to protect the chicks, even though their parents are actually chickens.” Examples of this design are present throughout the game. The bicycle and balloons (which symbolize dreams) on the title screen, the apartment resident in the bonus stage windows—all were meant to drive the point home that the chicks were children who were in mortal danger. The later stages developed this narrative. For example, the outer space background represented the future, one that would be cut short if Tiger and Iggy got their way. Such themes were not uncommon to games made by Kawasaki. None of his games featured characters dying, and he preferred to make friendlier and cuter games to counteract the bad reputation arcades had in Japan at the time (“Interview: Yoshiki Kawasaki”; Szczepaniak).

In development for a year, Flicky could have been much larger than it finally was. The design team had around 100 stages done but few backgrounds, and there was very little memory space left. Kawasaki opted to keep only four backgrounds, differentiating them by color, and the stages were reduced to a total of 40. After playtesting the game, the team added a monster that would appear in windows and breathe fire. Iggy was also conceived at this point, primarily to keep players from standing still in a stage. He ran throughout the level, making it unsafe to remain too long in a single spot. Kawasaki wasn’t too fond of the lizard because he was added at the end of development. He had wanted Iggy to be an insect, but his lack of motivation for the character made the design look more reptilian. During Flicky’s development, Kawasaki developed something of a reputation for taking such shortcuts, a behavior that earned him the humorous nickname “Sabori Kawasaki,” or “Slacker Kawasaki” (“Interview: Yoshiki Kawasaki”)

Flicky changed names twice during development. The original title of Busty was switched to Flippy due to a trademark issue in the U.S. (Bally/Midway also noted that “busty” was American slang for women with large breasts). The next choice, Flippy, was eventually deemed to sound too much like Mappy, so the title was changed again (“Interview: Yoshiki Kawasaki”; Szczepaniak). The game—with its final title of Flicky—was released in Japan in May 1984 and worldwide that September. A decent seller, it would sadly never receive a sequel. Ports of Flicky were released on multiple home consoles and later in compilations, and Flicky herself has made several cameos in other Sega games but has otherwise been forgotten as a character. The closest she’s come to fame has been in Sega’s Sonic the Hedgehog series as one of the animals released when Sonic defeated Eggman and cleared a zone. All the bird friends that Sonic rescues are called “flickies” and resemble her (“Flicky”).

While it’s unfortunate that Flicky has not been given a second chance, the original game remains an important step for both Ishii and Sega. Much of what Ishii learned from making Flicky would manifest itself in a major way in his masterpiece Fantasy Zone only two years later. His experience with Flicky would also be influential in his later work on other platformers like Teddy Boy Blues (both arcade and Master System versions) and Ristar (Genesis). Sega, on the other hand, got a solid maze-chase game that provided valuable experience to someone who would become one of its most talented and prolific producers. Ishii was part of a major pool of talent that would explode over the next few years, soaring to incredible heights on the wings of a little blue bird.

6 notes

·

View notes

Audio

There was a version of Flicky for the unsucessful Wondermega console, notable for its inclusion of a CD-Audio reworking of the main Flicky theme.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay but any TikTok this guy makes is gold but especially this one

30K notes

·

View notes

Text

youknow when kittens meow and their eyes get a bit smaller cos theur faces r so little they cant have their mouth and eyes all the way open at the same time I think about it so muxh

157K notes

·

View notes

Photo

do you think butch hartman knows how many eggs he cracked with this

130K notes

·

View notes

Text

My current favourite tiktok trend is the one where people wrap presents to look like something they're not and some people get ridiculous with it

Like:

✨The dedication ✨

165K notes

·

View notes

Text

i really am fascinated with the db cooper case both bc of the unsolved mystery aspect and because its very, very, very likely that the dude actually just fucking died on his way down and it would be objectively very funny if someone stumbled across his remains, ideally the parachute still cartoonishly attached and the sunglasses on

49K notes

·

View notes