Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The Burberry Case highlighted a plethora of challenges that a company can and will face in branding, especially one that was founded 150+ years ago and is currently operating in a world that is very different than the one it was founded in and grew up in. The actions of Rose Marie Bravo and her team show the way a company can stay true to its history and leverage those cognitive associations while also rebranding to position itself in customer's minds in a refreshed and desirable light.

From targeting "accessible luxury", to slashing the number of SKUs, to taking stricter control of their licensing agreements… these decisions felt incredibly intentional and focused.

As I think about our team's branding lab, at first there's not a lot of similarities between a 150+ year old clothing & accessory brand and a our project focused on developing the brand for a rural mountain region in Italy looking to attract remote working families. But what we can take away from this case is the importance of controlling the image, not trying to be too many things to too many people, and most importantly of all, being intentional.

It is tempting for us to try to paint the picture of Monti Prenestini as a place for everyone. But in many ways a place for everyone is a place for no one. From our understanding the region wants to attract young remote-working families and as such we need to make sure we position the brand of this region accordingly. We need to better understand what these families really want and need. Aspects such as reliable infrastructure (e.g. internet), ample childcare options, a great education system, family focused activities on the weekends, etc. will be important to put forward. Perhaps more so than other wonderful but less family oriented things Italy is known for such as great restaurants or shopping.

Monti Prenestini won't have the challenges (or benefits) of being a 150+ year old brand, but it's important that the cognitive associations with the country of Italy are considered in the branding of this specific region. Monti Prenestini will always be in Italy, and as such needs to be position as the "ideal place for a young remote-working family" looking to move to Italy or to/within Europe more broadly (but are open to the idea of Italy).

0 notes

Text

When reading Professor Gosline's article on the need for more friction in AI Customer Journey's, my mind kept coming back to the central need of simply asking questions and the importance of doing so. Yes, there is a inherently a massive value proposition in showing a customer what they want without them having to tell you what it is that they want. In many ways that's the holy grail. But at the same time, we as human beings also like to have say in there decisions - most want some degree of control. And that's where the good friction, specifically in the form of asking questions or providing information comes into play. It is so tempting and it is become so easy to use AI and take automation decisions too far. But as we risk taking this new technology and implementing it so pervasively in our lives, customers feeling like they have some degree of control is essential. And truthfully it's not only control, but even more importantly it's building trust. Trust that an algorithm is taking into consideration the factors that I as a customer value. Good friction can help build trust with a customer.

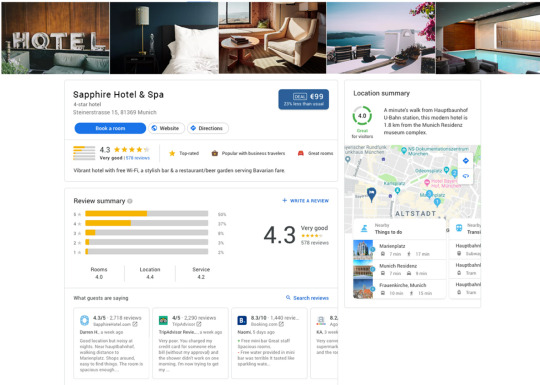

As I relate this to my group's branding lab, where were are thinking about how a rural village in Italy should be positioning itself to attract short term tourists and/or potential remote-working families, we need to ensure that we are focusing on the core mission of building trust between a potential tourist and the location. Whenever someone is searching for a vacation destination, they are bombarded with lists and list of potential locations, hotels, and activities. Targeted or not, it's hard to know what to trust and what not to.

Maybe you find a hotel with great looking photos at a steal of a price, but it's hard not to worry "is this too good to be true?". When we think about visiting a new place, inherently there is a leap of faith. Whether trusting a friends recommendation or a review from a google search, when we venture to a new location, whether it be to visit or to move there, we are taking a leap of faith. There is no substitute for actually experiencing that new place. As such, anything we can do to help foster that trust that our branding is authentic and that the reality will meet expectations is essential. Now the question is how can we create points of good friction with the customer where they feel that they are looking at a destination that actually fits what they are looking for.... this will be a fun one for our team to continue to tackle across the next few weeks!

0 notes

Text

Between the Concha y Toro case and the California vs North Dakota study, I couldn't help but think of how generously clueless I feel when walking into a wine shop and picking out a bottle. If you asked me how much I know about wine I would respond with "very little", but I do quite enjoy wine. And truthfully I would think I fall right around average. I have some familiarity with regions that are known for their wine. I have a general sense of different types of wine and which ones I prefer. But when I walk into a wine store... I feel excited when I see a bottle I've seen before as it makes me feel like I'm not totally clueless.

In my opinion, not many families of products have as much trouble with brand recognition as wine does. Yeah there are some bottom shelf wine brands that many people know (e.g. Yellow Tail) but generally speaking consumers of wine have much stronger associations with regions, price, or even the look of a wine label than any individual brand. My mind wonders what it is about wine that creates this phenomenon. The case seemed to make a mention of the way consumers of wine like to explore/experiment and I think this is certainly a major part of it. When experimentation is inherently a part of the wine experience for both experienced and inexperienced wine drinkers, it creates a phenomenon where consumers want bounds they can choose within (region and/or price point). Specific brands/vineyards simply don't offer enough choice. It seems to suggest that the Concha y Toro model as an umbrella brand over other brand name wines has the potential to be successful. Someone like myself might find themselves liking having a umbrella brand that I feel comfortable buying within, especially if it delivers on the perception of low price, high quality. This also feels like a recipe to get a customer like myself to maybe enter at a lower price range but be willing to take a step up for a special occasion or as my means allow because of trust I have in the quality of the umbrella brand. With keeping the challenges of a "bottom-up" strategy in mind, coming to the market with a range of brands under a parent company/brand and establishing themselves across the price ranges seems like a potentially viable way to establishing themselves. But then again, you can't be all things to all people and focusing on a customer segment is important. Wine truly poses a unique challenge for brands.

As a funny aside, recently in an effort to keep airline status for one more year, I took advantage of a miles sign up bonus for a wine delivery membership. $80 total for 14 wines... $5.71 a bottle. What a steal. While so far I've only worked through a few of the bottles, there's actually been quite a few I've really enjoyed. But as much as I enjoyed them, it's incredibly unlikely I make any effort to purchase any of those wines again. Not out of lack of enjoying them, but just because that's not how I and many others purchase wine.

0 notes

Text

My biggest takeaway from the two readings was how clearly nudging and experimentation go together. With 12 different types of nudges and a plethora of behaviors to encourage or discourage, without setting up an experiment, it's hard to argue that nudging wouldn't simply be shooting in the dark based on intuition. At the very least it feels like a massively missed opportunity to not build marketing experimentation and analytics around any set of implemented nudges.

With that being said, throughout the reading on experimentation my mind kept going back to some lessons from the Marketing Analytics class I took last Spring with Dean Eckles here at Sloan and pitfalls. While encouraging a do-it-yourself, grass roots experimentation culture has value, there are certain pitfalls to this that need to be avoided. Some that come to mind are ensuring experiments have sample sizes that have enough statistical power to identify statistically significant changes and ensuring the sampling and groups are split in a way that will maximize the cuts that can be analyzed. Most importantly though I think is ensuring that there is visibility across the organization so that various teams can learn from each others experiments and/or leverage and potentially repurpose the data from those experiments. Just as the article cites not missing out on "natural experiments", I also can't help but think it's important not to miss out on planned and well executed experiments going on within your own organization simply because of a lack of communication or visibility. Creating a culture of experimentation is essential, but ensuring the organization has visibility to that experimentation is really what takes it to the next level.

0 notes

Text

Is Premium Beer an Oxymoron?

I'll admit I was quite surprised to learn of Heineken's top position in the US as far as imported bears go. I cannot tell you a single friend or family member that I know that would pick up a case of Heineken for any sort of social gathering. When I think of Heineken, I think of the mini-keg that my roommates and I used solely to replace the broke leg of a couch in our summer apartment in DC (true story). The same cannot be said for Corona as I myself have picked up a case or two of Corona in my life. When I think of Corona, I'm not sure "premium" is what comes to mind, but what does come to mind is a something "different" and a bit more fun and enjoyable than Bud or Miller. I think Corona's Marketing is pretty spot on with the associations they've made to the beach and sort of life style. One challenge with this association though is the risk of Corona feeling seasonal. While the case exhibits didn't highlight seasonal trends, it feels weird to be drinking Corona on a cold winter night just as it feels weird to be drinking a Guinness on the beach. The larger mass-market beers such as Bud have created a brand around a beer that is for any time of day and day of the year. Heineken has definitely posited itself similarly. Corona may want to regionally shift its advertising away from the focus on on the association with the beach in areas such as the Mid-West or Northeast where those associations might make a customer less inclined to pick up a case of Corona during the colder half of the year.

One of the biggest things that jumped out to me in this case as is Heineken's campaign themed "Just being the best is enough". Beer, by it's very nature as a drink, is the most down to earth of all the groups of alcohol in my mind. While positioning a brand as the best has potential in theory, I wouldn't expect this to drive the most sales for the average beer drinking. It should be noted that the rise of craft breweries has changed the attitude towards bear to an extent in recent years, but a person that wants a craft beer from a local brewery is not the same person that will be buying a case of Heineken. I think Heineken was and is right to shift away from their positioning of arrogance and being "the best" and focus more on a perception of simply quality brewed beer.

1 note

·

View note