🥀 She/Her | 21 | Artist 🍓A blog dedicated to history and art

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

For those who are wondering what took me so long to post this. My reasons are because I was incredibly busy and burnout from school. At the same time, I worked on some techniques that helped improve my art. Like the shading for example, the story and the color contrast. I apologize for my delays and I hope to post more content soon. I am sorry if I took longer than anticipated. Tysm for your understanding.

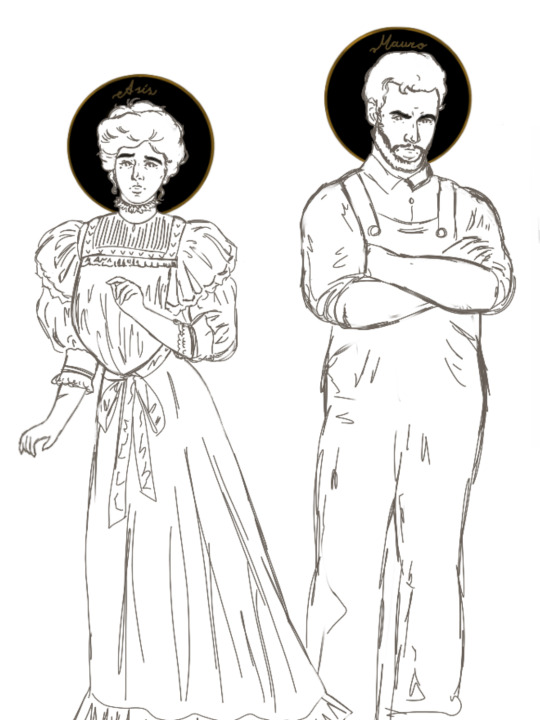

The Queen Mother's Farewell (Charles II, Maria Anna of Nueburg and Mariana of Austria Fanart)

Authors note: A story based on fact

1696 was a challenging year for Charles II of Spain, as repeated tragedies struck him in ways from which he could not recover. The king’s health began to deteriorate further, and Europe grew restless as he had yet to declare a successor to his throne. At this point, Charles, without descendants of his own, had to decide between José Fernando of Bavaria (the son of Maria Antonia of Austria and Maximilian II Emanuel of Bavaria), Philip of Anjou (the future Philip V of Spain), or Charles of Austria (the son of Leopold). Opinions varied on which candidate would succeed Charles II and be named in his will.

Mariana of Austria wanted José Fernando of Bavaria to be Charles II’s successor. In contrast, Maria Anna of Neuburg, Charles II’s second wife, opposed this idea and tried to persuade Charles to favor her nephew, Charles of Austria, believing he would be a better candidate than José Fernando. This conflict resulted in a competition between the two queens for Charles’s attention and favor. Caught in the middle, Charles was uncertain about whom to choose as his successor, realizing that the decision could either save or destroy Spain. He understood that he could not decide alone. In desperation, Charles II approached the person he loved and trusted the most: his mother, Mariana of Austria. He sought her advice on whether José Fernando was the rightful successor to the throne.

She held Charles’s hand, glanced at him, and said, “José Fernando is the best option we have. He is what’s left of Antonia, your niece, and Margarita. He is her grandson and a good fit for the succession, following the will of your father, Philip IV, which states that if you cannot sire an heir, then the succession shall pass to your sister or her descendants.” Despite his mother’s reassurance, Charles remained uncertain about naming José Fernando as heir in public. However, he did consider him a good candidate. Grateful for his mother's guidance, he was ready to leave when Mariana suddenly screamed in pain, clutching her chest. Charles II quickly sat her down and asked if she was all right. Mariana shrugged it off, assuring her son that she was well. Believing her, Charles advised her to rest for now.

Meanwhile, Mariana wrote pleading letters to Maximilian Emanuel of Bavaria: “May God preserve him for the comfort of your Highness and myself, for I carry that child in my heart, as it’s the only thing I have left of my daughter.” As she wrote, the pain in her chest tormented her, refusing anyone who dared to offer help.

Mariana despite her hidden pain is determined to perform her duties even if tensions grew between her and her daughter-in-law. Who at this time demanded more pension and control at court.

For months,The Queen Mother performed her duties as usual, helping Charles onpolicies and political decisions, doing charity work, visiting monasteries, wrote important letters, and praying. Though her daughter-in law was still a problem to her, Charles did not seem to notice anything strange from his mother.'

Tragically, the secret that Mariana had tried to conceal caught up with her as her condition worsened. The Queen struggled to sleep and endure her pain. On the morning of March 1696, She summoned the royal physician and showed him her tumor. The doctor was horrified seeing it. The size and color of the tumor shocked him. He thought to himself, “I didn’t expect Her Majesty’s condition to worsen.” Tears ran down the queens eye’s, as she laid still in her bed, helpless. Meanwhile, within the opulent walls of the Alcázar Palace, Charles was deep in conversation with his minister, the Duke of Oropesa about the ritual, This ritual was performed by this month to rid of evil humours accumulated during the winter, The preparations are well advanced at the palace, the barbers where ready to perform when suddenly a messenger burst into the room with alarming news.

“Your Majesty, the Queen Mother wishes to inform you that she is gravely ill,” he declared. The shock hit Charles, leaving him momentarily paralyzed by disbelief. “This cannot be! She was perfectly well just days ago,” he thought in anguish, his heart racing. As Maria Anna gently touched his shoulder, offering silent support, he instinctively embraced her, and amid the turmoil. They both went to the El Palacio de Duque de Uceda, Mariana of Austria lay in her dimly lit chamber, casting long shadows over her frail form. Pain pulsed through her body, the tumor within her an ever-growing curse.

She clenched her trembling hands, her voice barely above a whisper. “God has abandoned me,” she murmured bitterly. Tears welled in her eyes, spilling down her pale cheeks. “He took my children especially my Margarita. He denied my son the joy of fatherhood. Every night, I close my eyes to nothing but suffering.”

The priests stood at the foot of her bed, murmuring prayers, but she turned away from them, her heart too heavy with grief to seek their solace. The door creaked open, and Carlos, her son, entered the room. His face bore the solemn weight of both duty and love. Seeing his mother in such despair cut him deeply. He knelt beside her bed, wept, taking her cold, fragile hand in his own.

“Oh, my son!” Mariana whispered, gazing at him with weary eyes. “Upon my death, I ask only one thing of you. Make José Fernando your heir. He is our last hope.” Her voice wavered, but her resolve remained. “There is nothing left for me in this world. A new one awaits.”

Carlos gently pressed her hand, his own eyes glistening with tears. “My dear mother,” he said softly, “do not let sorrow steal your faith. If you abandon it now, how will you ever find paradise? Believe in God, and He will lift the burden of your pain.”

Mariana touched his left cheek, smiled at him, then closed her eyes, exhaling a shaky breath. Whether comforted or resigned, she did not say. Carlos spoke to his mother's physician,��inquiring about her condition. The physician told the king that they have to examine the Queen further to provide a proper diagnosis. With the permission of the King and Queen Mother herself, The physicians at last are permitted to examine her.

“Why was I informed about this now?!” Carlos asked, tears streaming down his face. “The Queen ordered us not to utter a word to you,” the physician replied.

Carlos was shocked and could hardly believe that his mother had kept her illness a secret from him for so long. He went back to his mother’s room and confronted her.

“My Mother, My lady, why? Why must you keep your suffering from me? Why must you suffer for me!?” Carlos asked.

“Because I could not bear to be part of your burdens, I would rather die than lose another son," Mariana muttered, her voice barely above a whisper as the weight of sorrow pressed upon her.

On April 5th 1696, In Madrid, The doctor’s officially certify the Queen's condition and release the information to the public.

“Six days ago, Most High Queen showed us her tumor that she has in her left breast of the magnitude and size of a newborn's head. Although it is not located between the ribs, it has its roots in them, and it advances, extending outward, with five or six hard growths visible on its surface. The whole surface of the tumor is hard and purple, and it causes pains that sometimes reach the ribs and prevent Her Majesty from sleeping at night. Veins swollen with bilious blood and purple spots like those produced by trauma can be observed in the tumor.

Its shape is irregular and horrible to look at, from all of which it can be deduced that it is a cancer of the kind spoken of by Galen, and which Cornelius Celsus calls “carcinoma.” It has not yet spread, but its color and the pain it causes suggest that it will spread soon. An attempt is being made to cure it by the preservative and palliative method, with the consent of the Venerable Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons, and efforts are being made to prevent the tumor from growing by using attenuating and evacuating medicines, that is, by eliminating the fibrous humors and trying to reduce them. May God, Optimus, and Maximus, restore Her Majesty's health and prolong her life for many years ”

The physicians tried to cure the Queen by resorting to supernatural remedies, transporting the bodies of San Isidro and the Virgin of Atocha to the Royal Alcazar, to which the royal family was very devoted. Carlos on the other hand, prayed for his mother’s recover. His wife Maria Anna prayed with him. Maria Anna tried her best concealing her her hatred for the Queen Mother. Maria Anna did wrote a letter to her family that Mariana of Austria had lost faith to the Venerable Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons, and her court doctors. Asking for the best German specialist available. Lancier, The bavarian ambassador wrote to the Elector that Mariana could live longer if, the doctors did not complicate her illness with their treatment, which alas, they were already doing, Their dosing made her vomit and increased her fever and had no good effect on her whatsoever.

Despite the doctors best efforts, By the month of May 1696, The tumor opened up and reached a more than considerable size (the head of a seven-year-old child).

The doctors brought a shaman from La Mancha to perform a ritual on the Queen Mother. By May 10 1696, It’s clear that the Queen’s end is near. The ritual of royal beds began to be performed.

She received the Viaticum in the presence of Carlos and Maria Anna. She bid farewell to Carlos and Maria Anna, though her farewell to her was less affectionate. Mariana could feel the end approaching, a cold certainty settling in her bones. Carlos clutched her frail hand, his fingers trembling. Tears welled in his eyes, spilling onto his cheeks as he whispered, "Mother, please, don't leave me." Mariana's gaze softened as she looked at her son, the boy she had fought for, the king she had raised. With the last of her strength, she squeezed his hand and managed a weak smile.

"You must be strong, Carlos," she said. "For Spain… for our family…" Carlos sobbed, resting his forehead against her hand, unwilling to let go. The room was silent except for his quiet cries. Carlos eventually let go of his mother’s hand and left. She then sent her confessor into the crowded antechamber to ask forgiveness to those she offended. She wrote a will and signed it with seven grandees as witness. The body of San Isidro arrived, still intact thanks to her, and the miraculous image of Our Lady of Atocha. The cross of Pope Puis V was placed on her hand and she waited for her death. But death did not come until six days later on May 16, 1696.

40 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi

Im, mahmoud , Palestine /gaza. person trying to satisfy his hunger and thirst with a little to a person with a compassionate and tender heart. Imagine waking up to find yourself sleeping in the streets of a ruin. 💔💔 This is my situation and the situation of my family. The war has destroyed all my dreams and ambitions and broken everything inside me. 🥺💔 Help me so that I can stand on my feet and sleep in a safe place. Help me, even with a little, so that I can eat the least amount of food, as I sit for hours without a single bite. 💔 The war has left me without food or shelter. 😔💔 I can barely wear the most worthless things. The least you can do for me can be a lot. 💔 I am waiting for your donation🥺

https://chuffed.org/project/127680-help-mahmoud-survive-in-gaza

✅️Vetted by @gazavetters, ( #564)✅️

I will share tysm

0 notes

Text

The Queen Mother's Farewell (Charles II, Maria Anna of Nueburg and Mariana of Austria Fanart)

Authors note: A story based on fact

1696 was a challenging year for Charles II of Spain, as repeated tragedies struck him in ways from which he could not recover. The king’s health began to deteriorate further, and Europe grew restless as he had yet to declare a successor to his throne. At this point, Charles, without descendants of his own, had to decide between José Fernando of Bavaria (the son of Maria Antonia of Austria and Maximilian II Emanuel of Bavaria), Philip of Anjou (the future Philip V of Spain), or Charles of Austria (the son of Leopold). Opinions varied on which candidate would succeed Charles II and be named in his will.

Mariana of Austria wanted José Fernando of Bavaria to be Charles II’s successor. In contrast, Maria Anna of Neuburg, Charles II’s second wife, opposed this idea and tried to persuade Charles to favor her nephew, Charles of Austria, believing he would be a better candidate than José Fernando. This conflict resulted in a competition between the two queens for Charles’s attention and favor. Caught in the middle, Charles was uncertain about whom to choose as his successor, realizing that the decision could either save or destroy Spain. He understood that he could not decide alone. In desperation, Charles II approached the person he loved and trusted the most: his mother, Mariana of Austria. He sought her advice on whether José Fernando was the rightful successor to the throne.

She held Charles’s hand, glanced at him, and said, “José Fernando is the best option we have. He is what’s left of Antonia, your niece, and Margarita. He is her grandson and a good fit for the succession, following the will of your father, Philip IV, which states that if you cannot sire an heir, then the succession shall pass to your sister or her descendants.” Despite his mother’s reassurance, Charles remained uncertain about naming José Fernando as heir in public. However, he did consider him a good candidate. Grateful for his mother's guidance, he was ready to leave when Mariana suddenly screamed in pain, clutching her chest. Charles II quickly sat her down and asked if she was all right. Mariana shrugged it off, assuring her son that she was well. Believing her, Charles advised her to rest for now.

Meanwhile, Mariana wrote pleading letters to Maximilian Emanuel of Bavaria: “May God preserve him for the comfort of your Highness and myself, for I carry that child in my heart, as it’s the only thing I have left of my daughter.” As she wrote, the pain in her chest tormented her, refusing anyone who dared to offer help.

Mariana despite her hidden pain is determined to perform her duties even if tensions grew between her and her daughter-in-law. Who at this time demanded more pension and control at court.

For months,The Queen Mother performed her duties as usual, helping Charles onpolicies and political decisions, doing charity work, visiting monasteries, wrote important letters, and praying. Though her daughter-in law was still a problem to her, Charles did not seem to notice anything strange from his mother.'

Tragically, the secret that Mariana had tried to conceal caught up with her as her condition worsened. The Queen struggled to sleep and endure her pain. On the morning of March 1696, She summoned the royal physician and showed him her tumor. The doctor was horrified seeing it. The size and color of the tumor shocked him. He thought to himself, “I didn’t expect Her Majesty’s condition to worsen.” Tears ran down the queens eye’s, as she laid still in her bed, helpless. Meanwhile, within the opulent walls of the Alcázar Palace, Charles was deep in conversation with his minister, the Duke of Oropesa about the ritual, This ritual was performed by this month to rid of evil humours accumulated during the winter, The preparations are well advanced at the palace, the barbers where ready to perform when suddenly a messenger burst into the room with alarming news.

“Your Majesty, the Queen Mother wishes to inform you that she is gravely ill,” he declared. The shock hit Charles, leaving him momentarily paralyzed by disbelief. “This cannot be! She was perfectly well just days ago,” he thought in anguish, his heart racing. As Maria Anna gently touched his shoulder, offering silent support, he instinctively embraced her, and amid the turmoil. They both went to the El Palacio de Duque de Uceda, Mariana of Austria lay in her dimly lit chamber, casting long shadows over her frail form. Pain pulsed through her body, the tumor within her an ever-growing curse.

She clenched her trembling hands, her voice barely above a whisper. “God has abandoned me,” she murmured bitterly. Tears welled in her eyes, spilling down her pale cheeks. “He took my children especially my Margarita. He denied my son the joy of fatherhood. Every night, I close my eyes to nothing but suffering.”

The priests stood at the foot of her bed, murmuring prayers, but she turned away from them, her heart too heavy with grief to seek their solace. The door creaked open, and Carlos, her son, entered the room. His face bore the solemn weight of both duty and love. Seeing his mother in such despair cut him deeply. He knelt beside her bed, wept, taking her cold, fragile hand in his own.

“Oh, my son!” Mariana whispered, gazing at him with weary eyes. “Upon my death, I ask only one thing of you. Make José Fernando your heir. He is our last hope.” Her voice wavered, but her resolve remained. “There is nothing left for me in this world. A new one awaits.”

Carlos gently pressed her hand, his own eyes glistening with tears. “My dear mother,” he said softly, “do not let sorrow steal your faith. If you abandon it now, how will you ever find paradise? Believe in God, and He will lift the burden of your pain.”

Mariana touched his left cheek, smiled at him, then closed her eyes, exhaling a shaky breath. Whether comforted or resigned, she did not say. Carlos spoke to his mother's physician, inquiring about her condition. The physician told the king that they have to examine the Queen further to provide a proper diagnosis. With the permission of the King and Queen Mother herself, The physicians at last are permitted to examine her.

“Why was I informed about this now?!” Carlos asked, tears streaming down his face. “The Queen ordered us not to utter a word to you,” the physician replied.

Carlos was shocked and could hardly believe that his mother had kept her illness a secret from him for so long. He went back to his mother’s room and confronted her.

“My Mother, My lady, why? Why must you keep your suffering from me? Why must you suffer for me!?” Carlos asked.

“Because I could not bear to be part of your burdens, I would rather die than lose another son," Mariana muttered, her voice barely above a whisper as the weight of sorrow pressed upon her.

On April 5th 1696, In Madrid, The doctor’s officially certify the Queen's condition and release the information to the public.

“Six days ago, Most High Queen showed us her tumor that she has in her left breast of the magnitude and size of a newborn's head. Although it is not located between the ribs, it has its roots in them, and it advances, extending outward, with five or six hard growths visible on its surface. The whole surface of the tumor is hard and purple, and it causes pains that sometimes reach the ribs and prevent Her Majesty from sleeping at night. Veins swollen with bilious blood and purple spots like those produced by trauma can be observed in the tumor.

Its shape is irregular and horrible to look at, from all of which it can be deduced that it is a cancer of the kind spoken of by Galen, and which Cornelius Celsus calls “carcinoma.” It has not yet spread, but its color and the pain it causes suggest that it will spread soon. An attempt is being made to cure it by the preservative and palliative method, with the consent of the Venerable Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons, and efforts are being made to prevent the tumor from growing by using attenuating and evacuating medicines, that is, by eliminating the fibrous humors and trying to reduce them. May God, Optimus, and Maximus, restore Her Majesty's health and prolong her life for many years ”

The physicians tried to cure the Queen by resorting to supernatural remedies, transporting the bodies of San Isidro and the Virgin of Atocha to the Royal Alcazar, to which the royal family was very devoted. Carlos on the other hand, prayed for his mother’s recover. His wife Maria Anna prayed with him. Maria Anna tried her best concealing her her hatred for the Queen Mother. Maria Anna did wrote a letter to her family that Mariana of Austria had lost faith to the Venerable Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons, and her court doctors. Asking for the best German specialist available. Lancier, The bavarian ambassador wrote to the Elector that Mariana could live longer if, the doctors did not complicate her illness with their treatment, which alas, they were already doing, Their dosing made her vomit and increased her fever and had no good effect on her whatsoever.

Despite the doctors best efforts, By the month of May 1696, The tumor opened up and reached a more than considerable size (the head of a seven-year-old child).

The doctors brought a shaman from La Mancha to perform a ritual on the Queen Mother. By May 10 1696, It’s clear that the Queen’s end is near. The ritual of royal beds began to be performed.

She received the Viaticum in the presence of Carlos and Maria Anna. She bid farewell to Carlos and Maria Anna, though her farewell to her was less affectionate. Mariana could feel the end approaching, a cold certainty settling in her bones. Carlos clutched her frail hand, his fingers trembling. Tears welled in his eyes, spilling onto his cheeks as he whispered, "Mother, please, don't leave me." Mariana's gaze softened as she looked at her son, the boy she had fought for, the king she had raised. With the last of her strength, she squeezed his hand and managed a weak smile.

"You must be strong, Carlos," she said. "For Spain… for our family…" Carlos sobbed, resting his forehead against her hand, unwilling to let go. The room was silent except for his quiet cries. Carlos eventually let go of his mother’s hand and left. She then sent her confessor into the crowded antechamber to ask forgiveness to those she offended. She wrote a will and signed it with seven grandees as witness. The body of San Isidro arrived, still intact thanks to her, and the miraculous image of Our Lady of Atocha. The cross of Pope Puis V was placed on her hand and she waited for her death. But death did not come until six days later on May 16, 1696.

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Queen Mother's Farewell (Charles II, Maria Anna of Nueburg and Mariana of Austria Fanart)

Authors note: A story based on fact

1696 was a challenging year for Charles II of Spain, as repeated tragedies struck him in ways from which he could not recover. The king’s health began to deteriorate further, and Europe grew restless as he had yet to declare a successor to his throne. At this point, Charles, without descendants of his own, had to decide between José Fernando of Bavaria (the son of Maria Antonia of Austria and Maximilian II Emanuel of Bavaria), Philip of Anjou (the future Philip V of Spain), or Charles of Austria (the son of Leopold). Opinions varied on which candidate would succeed Charles II and be named in his will.

Mariana of Austria wanted José Fernando of Bavaria to be Charles II’s successor. In contrast, Maria Anna of Neuburg, Charles II’s second wife, opposed this idea and tried to persuade Charles to favor her nephew, Charles of Austria, believing he would be a better candidate than José Fernando. This conflict resulted in a competition between the two queens for Charles’s attention and favor. Caught in the middle, Charles was uncertain about whom to choose as his successor, realizing that the decision could either save or destroy Spain. He understood that he could not decide alone. In desperation, Charles II approached the person he loved and trusted the most: his mother, Mariana of Austria. He sought her advice on whether José Fernando was the rightful successor to the throne.

She held Charles’s hand, glanced at him, and said, “José Fernando is the best option we have. He is what’s left of Antonia, your niece, and Margarita. He is her grandson and a good fit for the succession, following the will of your father, Philip IV, which states that if you cannot sire an heir, then the succession shall pass to your sister or her descendants.” Despite his mother’s reassurance, Charles remained uncertain about naming José Fernando as heir in public. However, he did consider him a good candidate. Grateful for his mother's guidance, he was ready to leave when Mariana suddenly screamed in pain, clutching her chest. Charles II quickly sat her down and asked if she was all right. Mariana shrugged it off, assuring her son that she was well. Believing her, Charles advised her to rest for now.

Meanwhile, Mariana wrote pleading letters to Maximilian Emanuel of Bavaria: “May God preserve him for the comfort of your Highness and myself, for I carry that child in my heart, as it’s the only thing I have left of my daughter.” As she wrote, the pain in her chest tormented her, refusing anyone who dared to offer help.

Mariana despite her hidden pain is determined to perform her duties even if tensions grew between her and her daughter-in-law. Who at this time demanded more pension and control at court.

For months,The Queen Mother performed her duties as usual, helping Charles onpolicies and political decisions, doing charity work, visiting monasteries, wrote important letters, and praying. Though her daughter-in law was still a problem to her, Charles did not seem to notice anything strange from his mother.'

Tragically, the secret that Mariana had tried to conceal caught up with her as her condition worsened. The Queen struggled to sleep and endure her pain. On the morning of March 1696, She summoned the royal physician and showed him her tumor. The doctor was horrified seeing it. The size and color of the tumor shocked him. He thought to himself, “I didn’t expect Her Majesty’s condition to worsen.” Tears ran down the queens eye’s, as she laid still in her bed, helpless. Meanwhile, within the opulent walls of the Alcázar Palace, Charles was deep in conversation with his minister, the Duke of Oropesa about the ritual, This ritual was performed by this month to rid of evil humours accumulated during the winter, The preparations are well advanced at the palace, the barbers where ready to perform when suddenly a messenger burst into the room with alarming news.

“Your Majesty, the Queen Mother wishes to inform you that she is gravely ill,” he declared. The shock hit Charles, leaving him momentarily paralyzed by disbelief. “This cannot be! She was perfectly well just days ago,” he thought in anguish, his heart racing. As Maria Anna gently touched his shoulder, offering silent support, he instinctively embraced her, and amid the turmoil. They both went to the El Palacio de Duque de Uceda, Mariana of Austria lay in her dimly lit chamber, casting long shadows over her frail form. Pain pulsed through her body, the tumor within her an ever-growing curse.

She clenched her trembling hands, her voice barely above a whisper. “God has abandoned me,” she murmured bitterly. Tears welled in her eyes, spilling down her pale cheeks. “He took my children especially my Margarita. He denied my son the joy of fatherhood. Every night, I close my eyes to nothing but suffering.”

The priests stood at the foot of her bed, murmuring prayers, but she turned away from them, her heart too heavy with grief to seek their solace. The door creaked open, and Carlos, her son, entered the room. His face bore the solemn weight of both duty and love. Seeing his mother in such despair cut him deeply. He knelt beside her bed, wept, taking her cold, fragile hand in his own.

“Oh, my son!” Mariana whispered, gazing at him with weary eyes. “Upon my death, I ask only one thing of you. Make José Fernando your heir. He is our last hope.” Her voice wavered, but her resolve remained. “There is nothing left for me in this world. A new one awaits.”

Carlos gently pressed her hand, his own eyes glistening with tears. “My dear mother,” he said softly, “do not let sorrow steal your faith. If you abandon it now, how will you ever find paradise? Believe in God, and He will lift the burden of your pain.”

Mariana touched his left cheek, smiled at him, then closed her eyes, exhaling a shaky breath. Whether comforted or resigned, she did not say. Carlos spoke to his mother's physician, inquiring about her condition. The physician told the king that they have to examine the Queen further to provide a proper diagnosis. With the permission of the King and Queen Mother herself, The physicians at last are permitted to examine her.

“Why was I informed about this now?!” Carlos asked, tears streaming down his face. “The Queen ordered us not to utter a word to you,” the physician replied.

Carlos was shocked and could hardly believe that his mother had kept her illness a secret from him for so long. He went back to his mother’s room and confronted her.

“My Mother, My lady, why? Why must you keep your suffering from me? Why must you suffer for me!?” Carlos asked.

“Because I could not bear to be part of your burdens, I would rather die than lose another son," Mariana muttered, her voice barely above a whisper as the weight of sorrow pressed upon her.

On April 5th 1696, In Madrid, The doctor’s officially certify the Queen's condition and release the information to the public.

“Six days ago, Most High Queen showed us her tumor that she has in her left breast of the magnitude and size of a newborn's head. Although it is not located between the ribs, it has its roots in them, and it advances, extending outward, with five or six hard growths visible on its surface. The whole surface of the tumor is hard and purple, and it causes pains that sometimes reach the ribs and prevent Her Majesty from sleeping at night. Veins swollen with bilious blood and purple spots like those produced by trauma can be observed in the tumor.

Its shape is irregular and horrible to look at, from all of which it can be deduced that it is a cancer of the kind spoken of by Galen, and which Cornelius Celsus calls “carcinoma.” It has not yet spread, but its color and the pain it causes suggest that it will spread soon. An attempt is being made to cure it by the preservative and palliative method, with the consent of the Venerable Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons, and efforts are being made to prevent the tumor from growing by using attenuating and evacuating medicines, that is, by eliminating the fibrous humors and trying to reduce them. May God, Optimus, and Maximus, restore Her Majesty's health and prolong her life for many years ”

The physicians tried to cure the Queen by resorting to supernatural remedies, transporting the bodies of San Isidro and the Virgin of Atocha to the Royal Alcazar, to which the royal family was very devoted. Carlos on the other hand, prayed for his mother’s recover. His wife Maria Anna prayed with him. Maria Anna tried her best concealing her her hatred for the Queen Mother. Maria Anna did wrote a letter to her family that Mariana of Austria had lost faith to the Venerable Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons, and her court doctors. Asking for the best German specialist available. Lancier, The bavarian ambassador wrote to the Elector that Mariana could live longer if, the doctors did not complicate her illness with their treatment, which alas, they were already doing, Their dosing made her vomit and increased her fever and had no good effect on her whatsoever.

Despite the doctors best efforts, By the month of May 1696, The tumor opened up and reached a more than considerable size (the head of a seven-year-old child).

The doctors brought a shaman from La Mancha to perform a ritual on the Queen Mother. By May 10 1696, It’s clear that the Queen’s end is near. The ritual of royal beds began to be performed.

She received the Viaticum in the presence of Carlos and Maria Anna. She bid farewell to Carlos and Maria Anna, though her farewell to her was less affectionate. Mariana could feel the end approaching, a cold certainty settling in her bones. Carlos clutched her frail hand, his fingers trembling. Tears welled in his eyes, spilling onto his cheeks as he whispered, "Mother, please, don't leave me." Mariana's gaze softened as she looked at her son, the boy she had fought for, the king she had raised. With the last of her strength, she squeezed his hand and managed a weak smile.

"You must be strong, Carlos," she said. "For Spain… for our family…" Carlos sobbed, resting his forehead against her hand, unwilling to let go. The room was silent except for his quiet cries. Carlos eventually let go of his mother’s hand and left. She then sent her confessor into the crowded antechamber to ask forgiveness to those she offended. She wrote a will and signed it with seven grandees as witness. The body of San Isidro arrived, still intact thanks to her, and the miraculous image of Our Lady of Atocha. The cross of Pope Puis V was placed on her hand and she waited for her death. But death did not come until six days later on May 16, 1696.

#digital art#17th century#digital painting#spain#charles ii of spain#habsburg#history lesson#sad stories#please reblog

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

the concept art is so fucking gorgeous I can’t

47K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Queen Mother's Farewell (Charles II, Maria Anna of Nueburg and Mariana of Austria Fanart)

Authors note: A story based on fact

1696 was a challenging year for Charles II of Spain, as repeated tragedies struck him in ways from which he could not recover. The king’s health began to deteriorate further, and Europe grew restless as he had yet to declare a successor to his throne. At this point, Charles, without descendants of his own, had to decide between José Fernando of Bavaria (the son of Maria Antonia of Austria and Maximilian II Emanuel of Bavaria), Philip of Anjou (the future Philip V of Spain), or Charles of Austria (the son of Leopold). Opinions varied on which candidate would succeed Charles II and be named in his will.

Mariana of Austria wanted José Fernando of Bavaria to be Charles II’s successor. In contrast, Maria Anna of Neuburg, Charles II’s second wife, opposed this idea and tried to persuade Charles to favor her nephew, Charles of Austria, believing he would be a better candidate than José Fernando. This conflict resulted in a competition between the two queens for Charles’s attention and favor. Caught in the middle, Charles was uncertain about whom to choose as his successor, realizing that the decision could either save or destroy Spain. He understood that he could not decide alone. In desperation, Charles II approached the person he loved and trusted the most: his mother, Mariana of Austria. He sought her advice on whether José Fernando was the rightful successor to the throne.

She held Charles’s hand, glanced at him, and said, “José Fernando is the best option we have. He is what’s left of Antonia, your niece, and Margarita. He is her grandson and a good fit for the succession, following the will of your father, Philip IV, which states that if you cannot sire an heir, then the succession shall pass to your sister or her descendants.” Despite his mother’s reassurance, Charles remained uncertain about naming José Fernando as heir in public. However, he did consider him a good candidate. Grateful for his mother's guidance, he was ready to leave when Mariana suddenly screamed in pain, clutching her chest. Charles II quickly sat her down and asked if she was all right. Mariana shrugged it off, assuring her son that she was well. Believing her, Charles advised her to rest for now.

Meanwhile, Mariana wrote pleading letters to Maximilian Emanuel of Bavaria: “May God preserve him for the comfort of your Highness and myself, for I carry that child in my heart, as it’s the only thing I have left of my daughter.” As she wrote, the pain in her chest tormented her, refusing anyone who dared to offer help.

Mariana despite her hidden pain is determined to perform her duties even if tensions grew between her and her daughter-in-law. Who at this time demanded more pension and control at court.

For months,The Queen Mother performed her duties as usual, helping Charles onpolicies and political decisions, doing charity work, visiting monasteries, wrote important letters, and praying. Though her daughter-in law was still a problem to her, Charles did not seem to notice anything strange from his mother.'

Tragically, the secret that Mariana had tried to conceal caught up with her as her condition worsened. The Queen struggled to sleep and endure her pain. On the morning of March 1696, She summoned the royal physician and showed him her tumor. The doctor was horrified seeing it. The size and color of the tumor shocked him. He thought to himself, “I didn’t expect Her Majesty’s condition to worsen.” Tears ran down the queens eye’s, as she laid still in her bed, helpless. Meanwhile, within the opulent walls of the Alcázar Palace, Charles was deep in conversation with his minister, the Duke of Oropesa about the ritual, This ritual was performed by this month to rid of evil humours accumulated during the winter, The preparations are well advanced at the palace, the barbers where ready to perform when suddenly a messenger burst into the room with alarming news.

“Your Majesty, the Queen Mother wishes to inform you that she is gravely ill,” he declared. The shock hit Charles, leaving him momentarily paralyzed by disbelief. “This cannot be! She was perfectly well just days ago,” he thought in anguish, his heart racing. As Maria Anna gently touched his shoulder, offering silent support, he instinctively embraced her, and amid the turmoil. They both went to the El Palacio de Duque de Uceda, Mariana of Austria lay in her dimly lit chamber, casting long shadows over her frail form. Pain pulsed through her body, the tumor within her an ever-growing curse.

She clenched her trembling hands, her voice barely above a whisper. “God has abandoned me,” she murmured bitterly. Tears welled in her eyes, spilling down her pale cheeks. “He took my children especially my Margarita. He denied my son the joy of fatherhood. Every night, I close my eyes to nothing but suffering.”

The priests stood at the foot of her bed, murmuring prayers, but she turned away from them, her heart too heavy with grief to seek their solace. The door creaked open, and Carlos, her son, entered the room. His face bore the solemn weight of both duty and love. Seeing his mother in such despair cut him deeply. He knelt beside her bed, wept, taking her cold, fragile hand in his own.

“Oh, my son!” Mariana whispered, gazing at him with weary eyes. “Upon my death, I ask only one thing of you. Make José Fernando your heir. He is our last hope.” Her voice wavered, but her resolve remained. “There is nothing left for me in this world. A new one awaits.”

Carlos gently pressed her hand, his own eyes glistening with tears. “My dear mother,” he said softly, “do not let sorrow steal your faith. If you abandon it now, how will you ever find paradise? Believe in God, and He will lift the burden of your pain.”

Mariana touched his left cheek, smiled at him, then closed her eyes, exhaling a shaky breath. Whether comforted or resigned, she did not say. Carlos spoke to his mother's physician, inquiring about her condition. The physician told the king that they have to examine the Queen further to provide a proper diagnosis. With the permission of the King and Queen Mother herself, The physicians at last are permitted to examine her.

“Why was I informed about this now?!” Carlos asked, tears streaming down his face. “The Queen ordered us not to utter a word to you,” the physician replied.

Carlos was shocked and could hardly believe that his mother had kept her illness a secret from him for so long. He went back to his mother’s room and confronted her.

“My Mother, My lady, why? Why must you keep your suffering from me? Why must you suffer for me!?” Carlos asked.

“Because I could not bear to be part of your burdens, I would rather die than lose another son," Mariana muttered, her voice barely above a whisper as the weight of sorrow pressed upon her.

On April 5th 1696, In Madrid, The doctor’s officially certify the Queen's condition and release the information to the public.

“Six days ago, Most High Queen showed us her tumor that she has in her left breast of the magnitude and size of a newborn's head. Although it is not located between the ribs, it has its roots in them, and it advances, extending outward, with five or six hard growths visible on its surface. The whole surface of the tumor is hard and purple, and it causes pains that sometimes reach the ribs and prevent Her Majesty from sleeping at night. Veins swollen with bilious blood and purple spots like those produced by trauma can be observed in the tumor.

Its shape is irregular and horrible to look at, from all of which it can be deduced that it is a cancer of the kind spoken of by Galen, and which Cornelius Celsus calls “carcinoma.” It has not yet spread, but its color and the pain it causes suggest that it will spread soon. An attempt is being made to cure it by the preservative and palliative method, with the consent of the Venerable Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons, and efforts are being made to prevent the tumor from growing by using attenuating and evacuating medicines, that is, by eliminating the fibrous humors and trying to reduce them. May God, Optimus, and Maximus, restore Her Majesty's health and prolong her life for many years ”

The physicians tried to cure the Queen by resorting to supernatural remedies, transporting the bodies of San Isidro and the Virgin of Atocha to the Royal Alcazar, to which the royal family was very devoted. Carlos on the other hand, prayed for his mother’s recover. His wife Maria Anna prayed with him. Maria Anna tried her best concealing her her hatred for the Queen Mother. Maria Anna did wrote a letter to her family that Mariana of Austria had lost faith to the Venerable Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons, and her court doctors. Asking for the best German specialist available. Lancier, The bavarian ambassador wrote to the Elector that Mariana could live longer if, the doctors did not complicate her illness with their treatment, which alas, they were already doing, Their dosing made her vomit and increased her fever and had no good effect on her whatsoever.

Despite the doctors best efforts, By the month of May 1696, The tumor opened up and reached a more than considerable size (the head of a seven-year-old child).

The doctors brought a shaman from La Mancha to perform a ritual on the Queen Mother. By May 10 1696, It’s clear that the Queen’s end is near. The ritual of royal beds began to be performed.

She received the Viaticum in the presence of Carlos and Maria Anna. She bid farewell to Carlos and Maria Anna, though her farewell to her was less affectionate. Mariana could feel the end approaching, a cold certainty settling in her bones. Carlos clutched her frail hand, his fingers trembling. Tears welled in his eyes, spilling onto his cheeks as he whispered, "Mother, please, don't leave me." Mariana's gaze softened as she looked at her son, the boy she had fought for, the king she had raised. With the last of her strength, she squeezed his hand and managed a weak smile.

"You must be strong, Carlos," she said. "For Spain… for our family…" Carlos sobbed, resting his forehead against her hand, unwilling to let go. The room was silent except for his quiet cries. Carlos eventually let go of his mother’s hand and left. She then sent her confessor into the crowded antechamber to ask forgiveness to those she offended. She wrote a will and signed it with seven grandees as witness. The body of San Isidro arrived, still intact thanks to her, and the miraculous image of Our Lady of Atocha. The cross of Pope Puis V was placed on her hand and she waited for her death. But death did not come until six days later on May 16, 1696.

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

This sketch is amazing 😻🤩

You did an excellent job

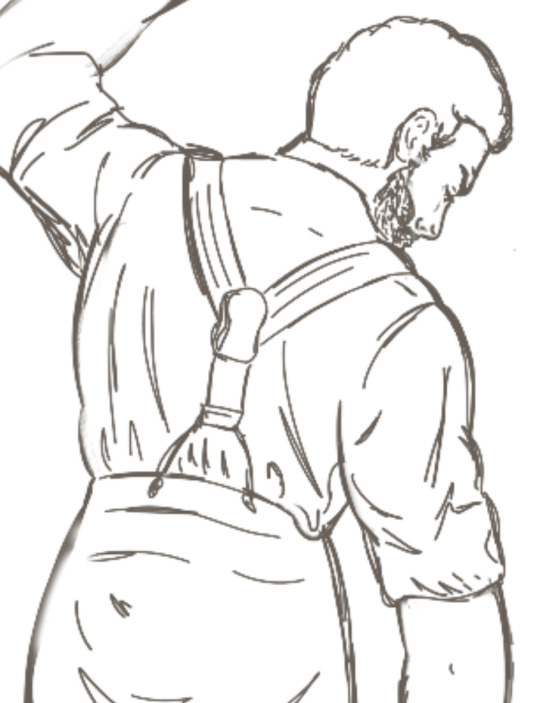

—NEW STORY, AND NEW OCS.

The other day @aneurinallday suggested I make a story with character based in my most recent actor crush, so today, challenge accepted 💪

>>His name was Mauro…, and he came from a little, obscure village, if that truly mattered. In a job like his, a man’s past, no matter how dark or how glorious, had little value.

So we are in the early 1900s. Mauro is fisherman living in an obscure little village in Spain, who has an even more obscure past. After a particularly dangerous storm ends, the sudden interruption of a dishevelled young woman seemingly come from nowhere (as there are no ships or land to be found being nearby) startles him by appearing in his ship, half-faint and much disoriented. He is quick to bring her back to land.

Soon enough, however, Asís (the girl) proves that she has too many a secret to keep; among them, that she is quite closely related to the past Mauro fights to forget. As strange things starts to occur in the once peaceful village, this two have to team up and try to solve everything before it is too late to do so.

(Also him :>)

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Queen Mother's Farewell (Charles II, Maria Anna of Nueburg and Mariana of Austria Fanart)

Authors note: A story based on fact

1696 was a challenging year for Charles II of Spain, as repeated tragedies struck him in ways from which he could not recover. The king’s health began to deteriorate further, and Europe grew restless as he had yet to declare a successor to his throne. At this point, Charles, without descendants of his own, had to decide between José Fernando of Bavaria (the son of Maria Antonia of Austria and Maximilian II Emanuel of Bavaria), Philip of Anjou (the future Philip V of Spain), or Charles of Austria (the son of Leopold). Opinions varied on which candidate would succeed Charles II and be named in his will.

Mariana of Austria wanted José Fernando of Bavaria to be Charles II’s successor. In contrast, Maria Anna of Neuburg, Charles II’s second wife, opposed this idea and tried to persuade Charles to favor her nephew, Charles of Austria, believing he would be a better candidate than José Fernando. This conflict resulted in a competition between the two queens for Charles’s attention and favor. Caught in the middle, Charles was uncertain about whom to choose as his successor, realizing that the decision could either save or destroy Spain. He understood that he could not decide alone. In desperation, Charles II approached the person he loved and trusted the most: his mother, Mariana of Austria. He sought her advice on whether José Fernando was the rightful successor to the throne.

She held Charles’s hand, glanced at him, and said, “José Fernando is the best option we have. He is what’s left of Antonia, your niece, and Margarita. He is her grandson and a good fit for the succession, following the will of your father, Philip IV, which states that if you cannot sire an heir, then the succession shall pass to your sister or her descendants.” Despite his mother’s reassurance, Charles remained uncertain about naming José Fernando as heir in public. However, he did consider him a good candidate. Grateful for his mother's guidance, he was ready to leave when Mariana suddenly screamed in pain, clutching her chest. Charles II quickly sat her down and asked if she was all right. Mariana shrugged it off, assuring her son that she was well. Believing her, Charles advised her to rest for now.

Meanwhile, Mariana wrote pleading letters to Maximilian Emanuel of Bavaria: “May God preserve him for the comfort of your Highness and myself, for I carry that child in my heart, as it’s the only thing I have left of my daughter.” As she wrote, the pain in her chest tormented her, refusing anyone who dared to offer help.

Mariana despite her hidden pain is determined to perform her duties even if tensions grew between her and her daughter-in-law. Who at this time demanded more pension and control at court.

For months,The Queen Mother performed her duties as usual, helping Charles onpolicies and political decisions, doing charity work, visiting monasteries, wrote important letters, and praying. Though her daughter-in law was still a problem to her, Charles did not seem to notice anything strange from his mother.'

Tragically, the secret that Mariana had tried to conceal caught up with her as her condition worsened. The Queen struggled to sleep and endure her pain. On the morning of March 1696, She summoned the royal physician and showed him her tumor. The doctor was horrified seeing it. The size and color of the tumor shocked him. He thought to himself, “I didn’t expect Her Majesty’s condition to worsen.” Tears ran down the queens eye’s, as she laid still in her bed, helpless. Meanwhile, within the opulent walls of the Alcázar Palace, Charles was deep in conversation with his minister, the Duke of Oropesa about the ritual, This ritual was performed by this month to rid of evil humours accumulated during the winter, The preparations are well advanced at the palace, the barbers where ready to perform when suddenly a messenger burst into the room with alarming news.

“Your Majesty, the Queen Mother wishes to inform you that she is gravely ill,” he declared. The shock hit Charles, leaving him momentarily paralyzed by disbelief. “This cannot be! She was perfectly well just days ago,” he thought in anguish, his heart racing. As Maria Anna gently touched his shoulder, offering silent support, he instinctively embraced her, and amid the turmoil. They both went to the El Palacio de Duque de Uceda, Mariana of Austria lay in her dimly lit chamber, casting long shadows over her frail form. Pain pulsed through her body, the tumor within her an ever-growing curse.

She clenched her trembling hands, her voice barely above a whisper. “God has abandoned me,” she murmured bitterly. Tears welled in her eyes, spilling down her pale cheeks. “He took my children especially my Margarita. He denied my son the joy of fatherhood. Every night, I close my eyes to nothing but suffering.”

The priests stood at the foot of her bed, murmuring prayers, but she turned away from them, her heart too heavy with grief to seek their solace. The door creaked open, and Carlos, her son, entered the room. His face bore the solemn weight of both duty and love. Seeing his mother in such despair cut him deeply. He knelt beside her bed, wept, taking her cold, fragile hand in his own.

“Oh, my son!” Mariana whispered, gazing at him with weary eyes. “Upon my death, I ask only one thing of you. Make José Fernando your heir. He is our last hope.” Her voice wavered, but her resolve remained. “There is nothing left for me in this world. A new one awaits.”

Carlos gently pressed her hand, his own eyes glistening with tears. “My dear mother,” he said softly, “do not let sorrow steal your faith. If you abandon it now, how will you ever find paradise? Believe in God, and He will lift the burden of your pain.”

Mariana touched his left cheek, smiled at him, then closed her eyes, exhaling a shaky breath. Whether comforted or resigned, she did not say. Carlos spoke to his mother's physician, inquiring about her condition. The physician told the king that they have to examine the Queen further to provide a proper diagnosis. With the permission of the King and Queen Mother herself, The physicians at last are permitted to examine her.

“Why was I informed about this now?!” Carlos asked, tears streaming down his face. “The Queen ordered us not to utter a word to you,” the physician replied.

Carlos was shocked and could hardly believe that his mother had kept her illness a secret from him for so long. He went back to his mother’s room and confronted her.

“My Mother, My lady, why? Why must you keep your suffering from me? Why must you suffer for me!?” Carlos asked.

“Because I could not bear to be part of your burdens, I would rather die than lose another son," Mariana muttered, her voice barely above a whisper as the weight of sorrow pressed upon her.

On April 5th 1696, In Madrid, The doctor’s officially certify the Queen's condition and release the information to the public.

“Six days ago, Most High Queen showed us her tumor that she has in her left breast of the magnitude and size of a newborn's head. Although it is not located between the ribs, it has its roots in them, and it advances, extending outward, with five or six hard growths visible on its surface. The whole surface of the tumor is hard and purple, and it causes pains that sometimes reach the ribs and prevent Her Majesty from sleeping at night. Veins swollen with bilious blood and purple spots like those produced by trauma can be observed in the tumor.

Its shape is irregular and horrible to look at, from all of which it can be deduced that it is a cancer of the kind spoken of by Galen, and which Cornelius Celsus calls “carcinoma.” It has not yet spread, but its color and the pain it causes suggest that it will spread soon. An attempt is being made to cure it by the preservative and palliative method, with the consent of the Venerable Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons, and efforts are being made to prevent the tumor from growing by using attenuating and evacuating medicines, that is, by eliminating the fibrous humors and trying to reduce them. May God, Optimus, and Maximus, restore Her Majesty's health and prolong her life for many years ”

The physicians tried to cure the Queen by resorting to supernatural remedies, transporting the bodies of San Isidro and the Virgin of Atocha to the Royal Alcazar, to which the royal family was very devoted. Carlos on the other hand, prayed for his mother’s recover. His wife Maria Anna prayed with him. Maria Anna tried her best concealing her her hatred for the Queen Mother. Maria Anna did wrote a letter to her family that Mariana of Austria had lost faith to the Venerable Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons, and her court doctors. Asking for the best German specialist available. Lancier, The bavarian ambassador wrote to the Elector that Mariana could live longer if, the doctors did not complicate her illness with their treatment, which alas, they were already doing, Their dosing made her vomit and increased her fever and had no good effect on her whatsoever.

Despite the doctors best efforts, By the month of May 1696, The tumor opened up and reached a more than considerable size (the head of a seven-year-old child).

The doctors brought a shaman from La Mancha to perform a ritual on the Queen Mother. By May 10 1696, It’s clear that the Queen’s end is near. The ritual of royal beds began to be performed.

She received the Viaticum in the presence of Carlos and Maria Anna. She bid farewell to Carlos and Maria Anna, though her farewell to her was less affectionate. Mariana could feel the end approaching, a cold certainty settling in her bones. Carlos clutched her frail hand, his fingers trembling. Tears welled in his eyes, spilling onto his cheeks as he whispered, "Mother, please, don't leave me." Mariana's gaze softened as she looked at her son, the boy she had fought for, the king she had raised. With the last of her strength, she squeezed his hand and managed a weak smile.

"You must be strong, Carlos," she said. "For Spain… for our family…" Carlos sobbed, resting his forehead against her hand, unwilling to let go. The room was silent except for his quiet cries. Carlos eventually let go of his mother’s hand and left. She then sent her confessor into the crowded antechamber to ask forgiveness to those she offended. She wrote a will and signed it with seven grandees as witness. The body of San Isidro arrived, still intact thanks to her, and the miraculous image of Our Lady of Atocha. The cross of Pope Puis V was placed on her hand and she waited for her death. But death did not come until six days later on May 16, 1696.

#history#house of habsburg#art#spain#17th century#charles ii of spain#mariana de austria#habsburg#please like and reblog#carlos ii#maria anna#maria#maria anna of nueburg#tragic#sad stories#digital painting#digital art#my art#mariana's art#cancer#tw cancer#breast cancer#historical figures#historical fiction#historical#17th century fashion#this is so sad#sorry for the delay#writing problems#To my dear followers tysm for your time and patience

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Camille Desmoulins Climbs On Outdoor Furniture Day, everyone!

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

Real 😭 At least Carlos achieved and helped people in his lifetime

Imagine calling yourself the history boy then try to roast a guy who was sick and disabled and still get the date wrong

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maria Doyle Kennedy as Catherine of Aragon The Tudors 1.02 Simply Henry (2007-2010)

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

yass queen so true

I made this side blog to cry about what a dishonor and disservice TSP has done to my COA. What an insult and for what?? They did the same thing with EOY and Margaret Beaufort but this is so bad I want to cry. Catherine doesn't deserve this.

#the spanish princess#tsp#anti the spanish princess#i am so upset#about so many things#catherine of aragon#anti philippa gregory#anti emma frost

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Spanish Princess 2x04 Reaction

Oh, sweet Jesus did this episode piss me the HELL OFF!! Get ready everybody because it’s gonna be a bumpy ride.

Keep reading

25 notes

·

View notes

Note

why are Philippa Gregory's and Alison Weir's works so popular?? i see so many TV shows and movie adaptations based on their work and they are two of the most biased, historically inaccurate authors i can think of. it really bothers me. are their takes really as popular amongst historians?

those who don’t like to be challenged (in fiction, and honestly … in life , and thus non-fiction) like stories where the heroes and the villains are easily identifiable. ‘those’ seems to be , honestly , most people. weir is the equivalent of marvel movies and pgreg is the equivalent of … hmmm… vc andrews? (i kind of like vc andrews tho lol from a like , anthropological , cultural touchstone kind of vantage point … i’d honestly shrug a lot more about pgreg’s stuff if she’d stuck to. yk. fictional incest … don’t even get me started on how the character template of the anti-heroine of wideacre was simply just transferred to anne in tobg—)

i would say, weir more so but pgreg is still invited (and i think she actually has hosted a few ? lol?) on documentaries and such… so like , kind of. yeah. i miss when historians were bitchier about weir, im ngl…. i think the last time she was really truly challenged by accredited historians was when john guy posted his ‘review’ which was a name and shame of lady in the tower (based on his wife julia fox’s forensic look at the evidence regarding jane boleyn, iirc), her AB biography. even dan jones ‘wtf’ comment on facebook about weir’s ‘theory’ that hviii was a virginity detector after all, and anne of cleves was not only not a virgin upon marriage , but has had an illegitimate child prior to marriage …was deleted by him within like . the same day??

tl; dr she just has a chokehold on this field and it’s really really depressing. i wish more historians would grow a backbone when it comes to denouncing the delulu shit she puts out , i really do…

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Tudors “Margaret” Tudor and purposeless character assassination: A rant.

(This is today’s rant subject, “Margaret” Tudor. Of course, no hate to Gabrielle Anwar, the actress that portrayed her; she has far better roles than this… Bitter princess)

“ICONIC” MARGARET?

(Some) People find it brutally empowering to see this refined lady murder her husband. And certainly, they first present her a very undesirable situation where we cannot do nothing but to be biased in her favour: We have a handsome gentleman of noble birth named Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk (played by the equally handsome Henry Cavill), who she has the hots for, and then, this dying, stinky pervert (Manuel I, King of Portugal) that we don’t know exactly why had she married (specially since, both historically and in the show, he had already a vast, healthy progeny). She has to bear with this torture until she says “no more of this” and decides to smother the king and hastily marry the Duke of Suffolk, her true love.

Well, this is when we get three big things wrong:

Firstly, murder remains an inexcusable crime in most of the cases. Imagine a young man killing his elderly wife in that same way. “But men have more authority and bodily autonomy!” It’s. Still. Murder. Henry VIII killed his wives (and many other innocent women both related and unrelated to him) to get with the woman/en he wanted, and we loathe him for that; but in this show, Margaret kills her husband to go back to Suffolk’s torrid embrace, (some( people find it iconic, girlboss, empowering.

Secondly, The Tudors is guilty of the punishable mistake of disguising lust as “passionate love”. We see it in Henry VIII / Anne Boleyn, and we see it in Margaret / Suffolk too. We soon learn that Margaret and the Duke have little to nothing in common, and that they spent most of their times fighting or separate (time that he idly spends in getting under the farthingales of ladies and trying to woo more women above his possibilities, just like the married and very fictional queen Claude of France). Just because he says “I’m sorry” before her grave that doesn’t make this a tragic love story.

Thirdly, she is no empowered character that we should take example of. Even after “freeing” herself from the King of Portugal, she spends most of her time bemoaning her life and the marriage she killed for. And that scene of her disapproving her brother’s ��unnatural” divorce by saying: “Oh, I won’t step into a court where a whore rules”. Miss, you literally bedded Suffolk before marrying the King of Portugal, then mercilessly killed your husband, then brought Suffolk back to warm your black widow’s bed and smugly told your brother. Your actions are as bad as Henry’s.

FANCY PRINCESSES DON’T WEAR THAT

As it happens whenever I encounter some The Tudors costume, I felt the dread of seeing clothes that neither of them would have ever worn. Margaret’s dress could have been very cool, but certainly, it had something that I didn’t enjoy. Her hairstyle, as pretty as it is, wouldn’t have been possible nor fashionable in those times, since she would have worn a proper headdress.

(This is a latter impression of Gossaert’s Wedding Portrait of the Dukes of Suffolk, which portrays the real Margaret, whose name was actually Mary, and the real Charles Brandon)

As you can see, the show counterpart misses a proper headdress, jewellery and the French gown that we are so used to see in Mary. She also seemed to borrow a crown from her sworn enemy Anne Boleyn apparently (in the show). I read in the WiKi that Margaret is a rebellious soul that wears unfashionable clothes, which highly contradicts the fashionable Mary Tudor, who brought the French fashions to court. Her clothes in the masque (everyone’s, actually) are highly historically inaccurate, and it is giving cheap copy of Fifty Shades Darker.

WILL THE REAL QUEEN PLEASE STAND UP? Manuel I of Portugal indeed remarried with a young princess, but this wasn’t any Tudor princess, but an Hapsburg one: Her name was Eleanor of Austria, and would become a widow three years of marriage and two children together after. Who Mary Tudor actually married was the King of France, Louis XII, who lacked male heirs (he only had two surviving daughter, the future Queen Claude, and Renee of France) who was fifty two when she was eighteen. And, despite making her brother swear to allow her to remarry in case she widowed (which is far more reasonable than what she did in the show), she was actually pretty kind to her sick, elderly husband, and he was very pleased with her too. Within months of marriage, he sent a letter to King Henry VIII calling him “brother” and expressing his upmost pleasure to be married to her. Mary may have been aware since her childhood, seeing her older siblings marry strategically into the Royal House of Scotland and Castile - Aragon, that she would suffer the same fate, and that she would have to be strong and a worthy sovereign to whatever kingdom she would be bound to reign; though I wouldn’t be so bold to say that she eventually loved him, Mary didn’t openly show her disgust to the king and treated him nicely. He suffered a long and painful agony due to his gout and died barely three months after marrying Mary. She spent some cautionary time in France, in case it was proven that she was with child, and then left.

Princess Mary Tudor, firstly Queen of France and later Duchess of Suffolk, was a pretty interesting character that was slain by the poor writing of the show runners, whose main focus revolves around her (quite unhealthy) sexuality and her good looks; then, after having her becoming a “burden” to Suffolk, they hastily had her killed and, after giving him some cheap ass redemption by looking mildly sad in her funeral (when he was literally bedding another woman as she agonised)m the next chapter comes and he already had set his eyes on his ward (which is nearly an adopted child, but with personal interests). Ironically, the true Charles Brandon had originally betrothed Catherine Willoughby to his son, then married her roughly two months after Mary’s demise; she was fourteen, and he fourty nine, making him thirty five years her senior, which in the show they dismiss quickly. Their age gap was one year bigger than that of the true Mary and Louis XII, but, quite the contrary of the first one, they never dare to make it undesirable in the show. Hypocrisy, I think.

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

Some say Elizabeth of York was overshadowed by her mother-in-law Margaret Beaufortt and didn't like each other?

No, I disagree.

I think Elizabeth of York and Margaret Beaufort had a harmonious relationship and consistently worked together in both political and familial matters. We know that Margaret spoke about her affectionately in her letters, and Elizabeth seems to have trusted her during times of crisis: for example, during the Cornish uprising in 1497, she took her children and fled first to Margaret’s townhouse, with the two of them then making their way to the Tower of London together. It’s important to remember that they had known each other for a while from the time of Elizabeth’s childhood: her parents seem to have liked Margaret, even naming her godmother for their youngest child, Bridget. They also shared familial links beyond Henry and Elizabeth’s marriage, as her sister Cecily of York was married to Margaret’s younger half-brother, John Welles. After Cecily’s love marriage to Sir Thomas Kymbe after being widowed, it was Margaret who protected her from Henry VII’s anger.

It’s clear that Elizabeth of York was fully capable of asserting herself and making her own decisions independently of her mother-in-law, as she did so on multiple recorded (and presumably, many more unrecorded) occasions. For example, while she and Margaret jointly supported the candidature of Thomas Pantry for an office at Oxford University in 1500, Elizabeth supported an opposing candidate the following year. So, she was clearly willing and able to make autonomous decisions based on her own preferences and priorities. That she and Margaret cooperated closely despite this can only mean that they had a positive – rather than negative – relationship, probably enhanced by their mutual desire to see their dynasty succeed.

All of this being said, I really dislike revisionist historians who, in their efforts to highlight this positive relationship between Margaret Beaufort and her daughter-in-law, end up diminishing and infantilizing Elizabeth of York in the process. This is usually done by claiming that Margaret was some kind of seasoned mentor figure with Elizabeth as a usually naïve and sheltered protégé under her tutelage, entirely dependent on her for guidance. Elizabeth of York was not a child, not inexperienced, and not an unaccustomed foreign bride – she was a 20-year-old adult woman who had faced immense hardships the past few years and had been trained to be queen her whole life. This is the same woman who perfectly navigated her uncle's court despite him murdering her brothers, persecuting her mother and maternal kin and bastardizing her; this is the same woman whose potential queenship was feared by Richard's associates because they believed she would seek to avenge her maternal family if she was ever crowned queen. How on earth can anyone claim she lacked experience or that she was unable to stand up for herself when she needed to? Elizabeth was also an English princess who had been raised at the heart of the English court and would have had far more in-built connections there than Henry or Margaret (neither of whom were in the political centre of anything before 1485) would have had.

Another reason I dislike this interpretation is that it ends up virtually erasing Elizabeth Woodville – Elizabeth of York’s mother who we know she was close to and relied on for comfort, whose unusually powerful queenship Elizabeth would have been able to observe firsthand her whole life. Her mother is similarly erased when people overemphasize the entirely unknown relationship between Elizabeth of York and Anne Neville due to one single Christmas PR gathering. (It’s almost like it’s a pattern or something).

All of this is exemplified by Elizabeth of York and Margaret Beaufort’s joint commission to Caxton in 1491 to print The Fifteen O’s of St. Bridget of Sweden. It has often been assumed that Margaret was the driving force behind this given her extensive patronage, with Elizabeth as a supporting protégé. “However, a recurring marginal pattern within the book hints at a different interpretation: most of the border patterns are of stylized flowers, mythical beasts, and semi-human creatures, quite possibly reused from other books, but one is of a vase of gillyflowers, the emblem of Elizabeth Woodville, whose family had been such important patrons of Caxton, and just over half-way up the margin these flowers lead into a rose branch, crowned with the emblem of her daughter's marriage, the Tudor rose, as if in reference to Elizabeth of York's adoption of her mother's patronage.” (Laynesmith). Contrary to popular perception, it seems that this was Elizabeth of York’s initiative, inspired by her own mother and maternal family, with Margaret Beaufort taking on a supporting and secondary role.

Similarly, there is an equally patronizing revisionist trend of acknowledging that Henry VII and Elizabeth of York were in a happy marriage and that he treated her well, while also portraying her as passive and claiming that he excluded her from politics (sometimes making the marriage happy precisely because of that). I've spoken about this before, but this misunderstands the nature of queenship at that time, which was inherently political. Elizabeth's queenship was more conventional when compared to her mother's and Margaret of Anjou's, but she was active and important in those spheres, and her activities & channels of influence were generally not much different from theirs, or from her successors. It also ignores the fact that we know Elizabeth felt comfortable expressing her wishes to Henry VII and we know that he listened to her. In 1498, a letter from Pope Alexander to Margaret Beaufort revealed that they had suggested a candidate for the bishopric to Henry, but the king explained that he had already promised Elizabeth that he would appoint her confessor. This can’t be used to determine levels of influence perse – Henry wasn’t choosing one over the other, as he had already promised Elizabeth her candidate before– and it wasn’t anything out of the norm, but regardless, “this degree of influence by the queen in a sphere in which we are accustomed to think of Henry acting alone comes as something of a surprise” (Malcolm Underwood).

Elizabeth was no doormat and was fully capable of disagreeing with Henry publicly on other occasions, as evidenced by this report by De Pablo:

“The King had a dispute with the Queen because he wanted to have one of the said letters to carry continually about him, but the Queen did not like to part with hers, having sent the other to the Prince of Wales.”

In conclusion - Elizabeth of York does seem to have been very gracious and was probably a soft touch (like her siblings and her father), but there is no reason to assume that she was overshadowed by her mother-in-law or that she was unable to assert herself with Henry VII. Quite the opposite on both accounts.

Hope this helps! I'm sorry for the delay in responding.

25 notes

·

View notes