Video

youtube

"Chiquitita" was the lead single from ABBA's album Voulez-Vous (1979). It was included in the Music for UNICEF Concert, with half its global profits donated to the U.N. organization. Released at the height of the group's musical prowess and commercial popularity, the song is not without its infelicities. The title name seems to have too many syllables and the song's romping piano hall (or is it circus finale?) coda is brazenly tacky. Nevertheless, "Chiquitita" is the finest example of a tricky pop genre which ABBA had mastered with previous hits like "Fernando," "Dancing Queen," and "Knowing Me, Knowing You"--a melancholy or sad song with a ringing, irresistibly positive, hooky chorus that blazes with upbeat harmony and conviction. When Agnetha and Frida swoop down on the bereft Chiquitita to inform her "you will have no time for grieving," we believe them--the melodic momentum admits no resistance. Ulvaeus and Andersen probably first encountered this sub-genre in early 1970s hits like "Alone Again, Naturally" (1972) by Gilbert O'Sullivan, Bo Donaldson and the Heywoods' "Billy, Don't Be a Hero" (1974), the sublimely mawkish Terry Jacks singing Jacques Brel's "Seasons in the Sun" (1974), but ABBA takes it to an entirely different level, magisterially sweeping all traces of lingering gloom before them.The aggressively wholesome "Chiquitita" video appears to have been shot on the abandoned set of 1960s Christmas TV special. The imposing snow colossus behind them introduces distracting issues of scale. Making music videos in the pre-MTV era was a casual affair, as we see here. Frida has a hard time with the wind machine, but clearly no one thought a second take was in order. And who is that guy who walks in from the right, then down behind the snow colossus?

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

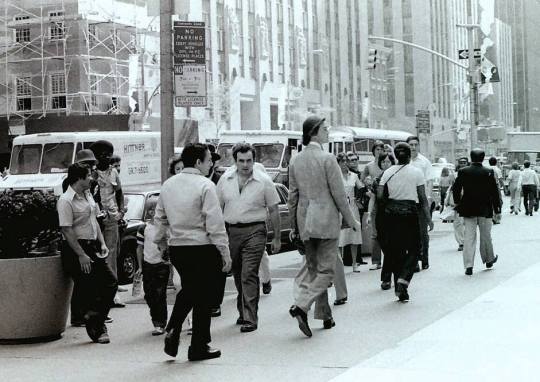

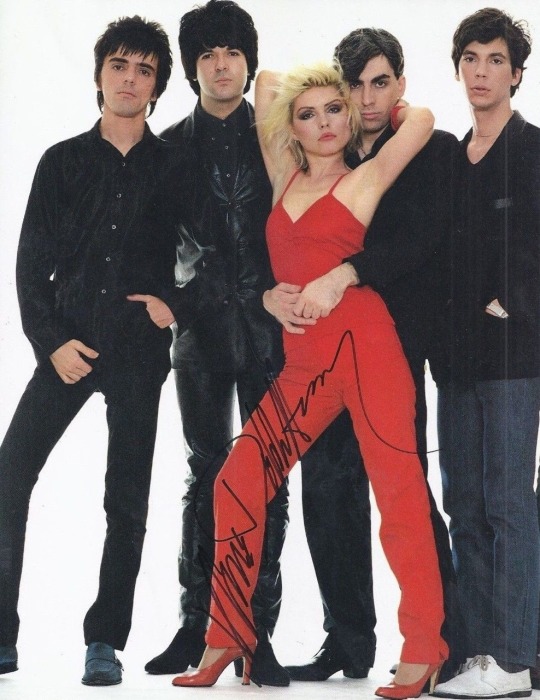

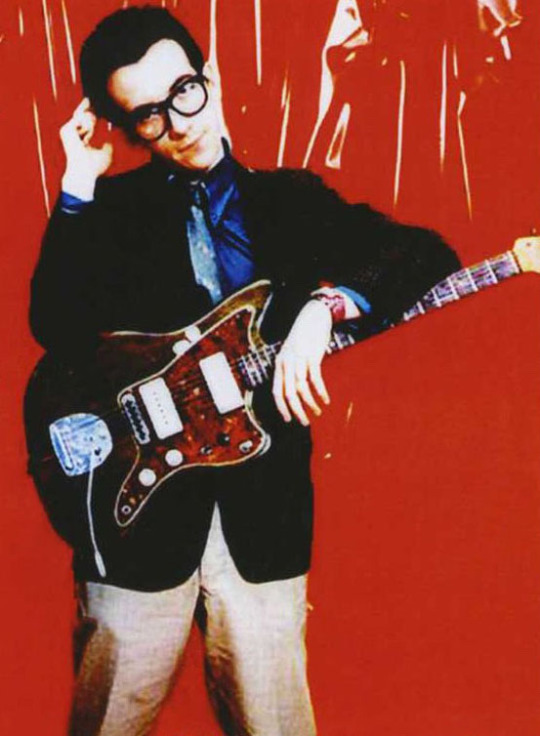

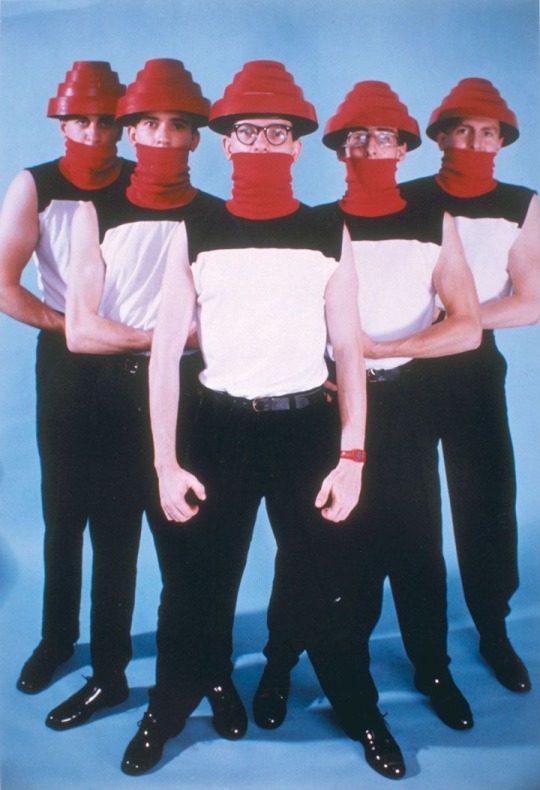

LE ROUGE ET LE NOIR

The elemental, red and black color combination popularized around 1980 by punk and new wave bands ushered in a decade of bright, saturated, artificial color that replaced the faded, natural and earth-tones favored by the counterculture.

170 notes

·

View notes

Text

Driving this 1971 Sebring Corvette Stingray, John Greenwood and Bob Johnson won the annual 4-hr race at the Michigan International Speedway (near Brooklyn, MI) on 4 July 1971. The car is shown here, earlier that year, at Daytona Beach, Florida.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

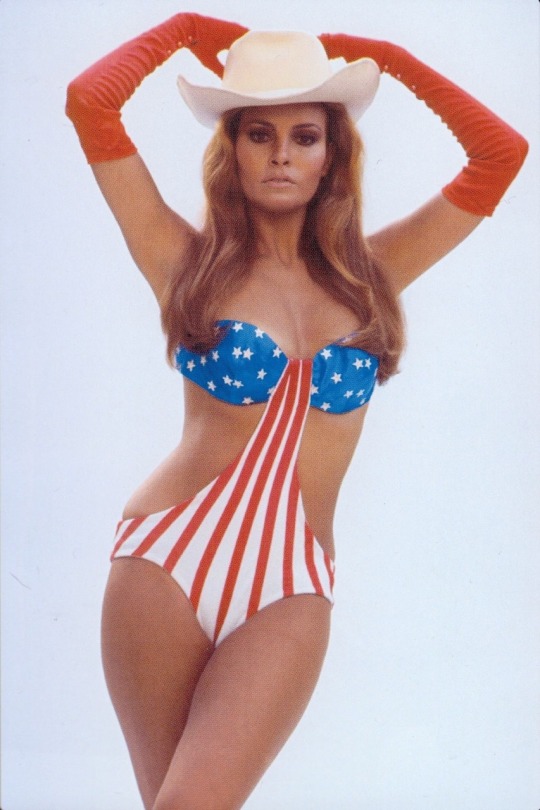

RACHEL WELCH in the film adapation of Gore Vidal's novel, Myra Breckinridge (1970). Directed by Michael Sarne, the sensational, incoherent, and, for the most part, just plain bad, film, was the most talked-about cinematic release of the year. Vidal renounced the fiasco early on. The plot follows the gender transition of Myron (played by Rex Reed) to Myra while attempting to give an account of the history of Hollywood at the same time. Mae West appears stars as a libidinous octagenarian agent. It's not clear Welch understands what the film is about, but she looks great and works hard to keep things moving along.

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

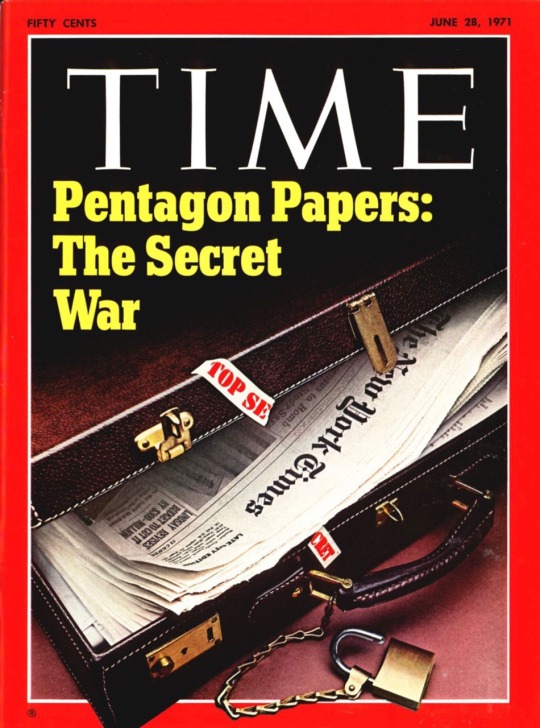

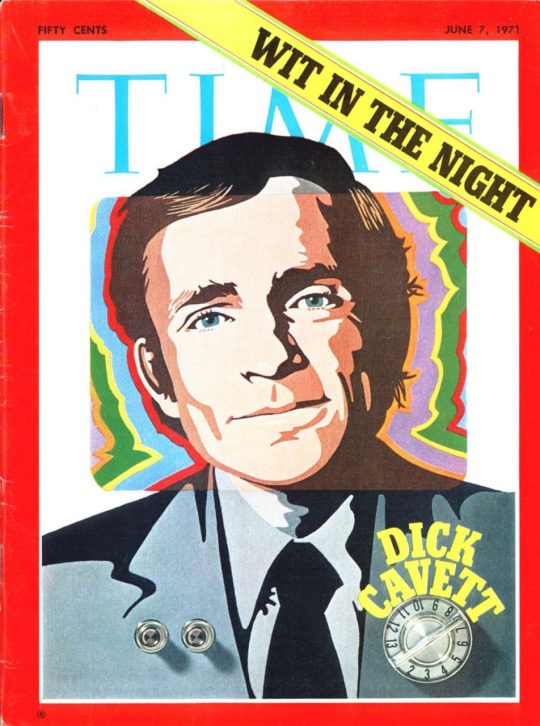

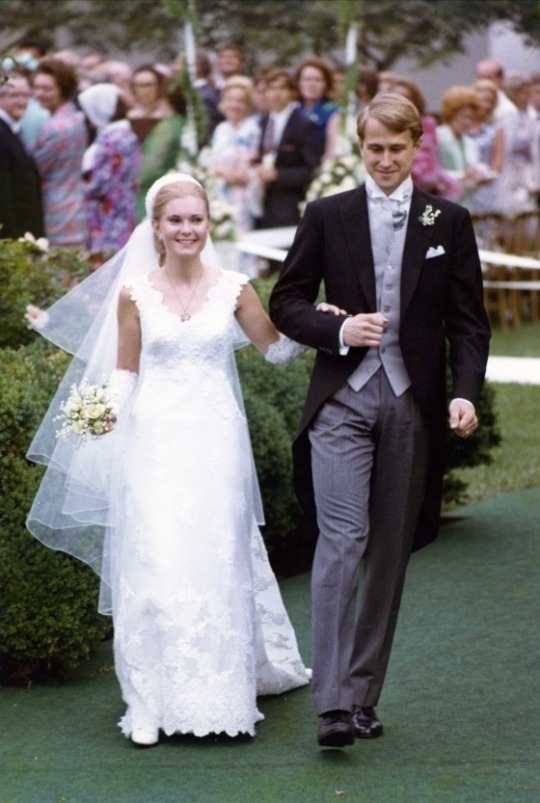

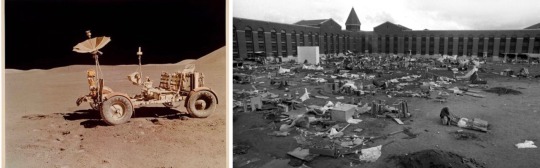

1971

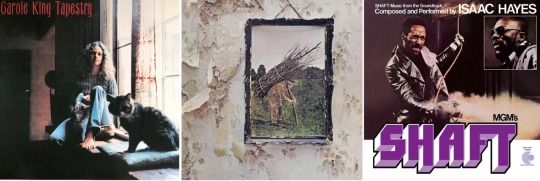

50 years later ... World Trade Center under construction; Wedding of Patricia Nixon and Edward,Cox, White House, 12 June 1971; Anonymous, Go Ask Alice; The Last Picture Show (dir. Peter Bogdanovich), The French Connection (dir. William Friedkin); Apollo 14 Moon Landing; Attica State Prison Riot, 9-13 September 1971; 1971 Chevrolet Vega; Carole King, Tapestry, Led Zeppelin IV, Shaft Soundtrack; Times Square, New York City; Bangladesh Independence War; Sylmar Earthquake, Los Angeles, 9 February, 1971; Yves Saint Laurent Collection 1971.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

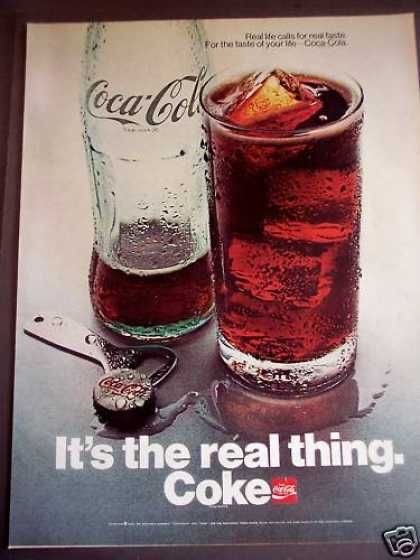

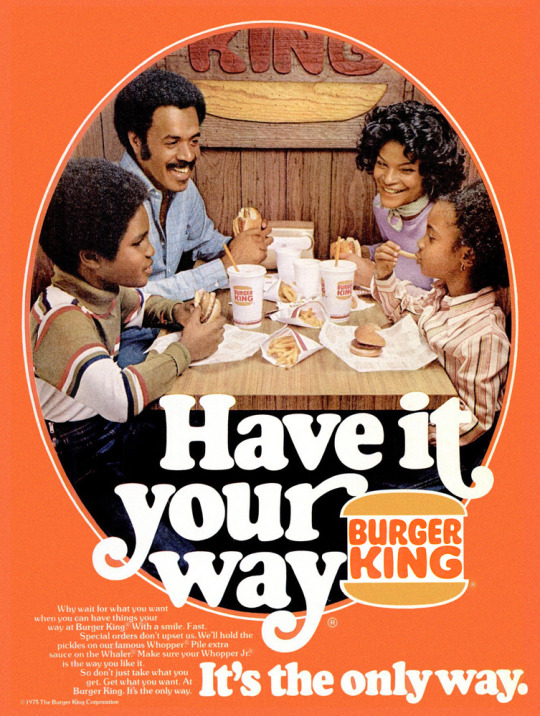

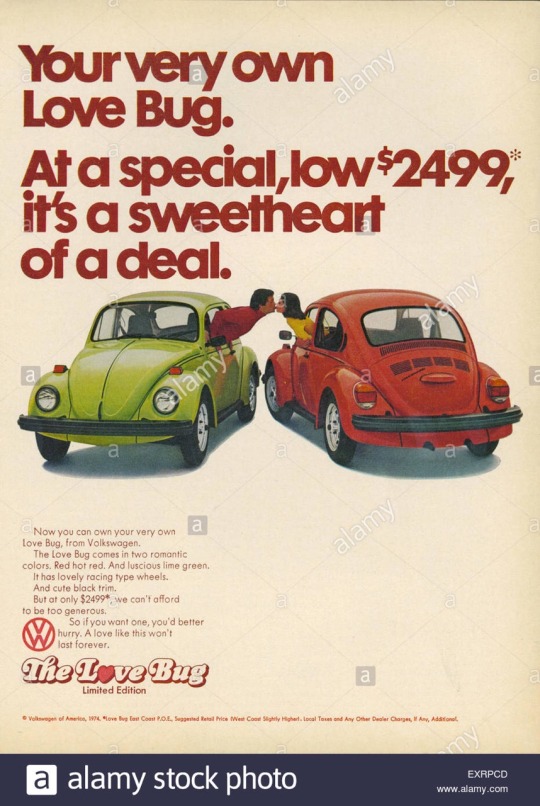

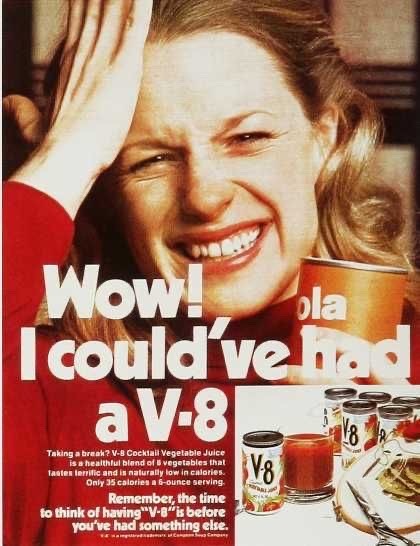

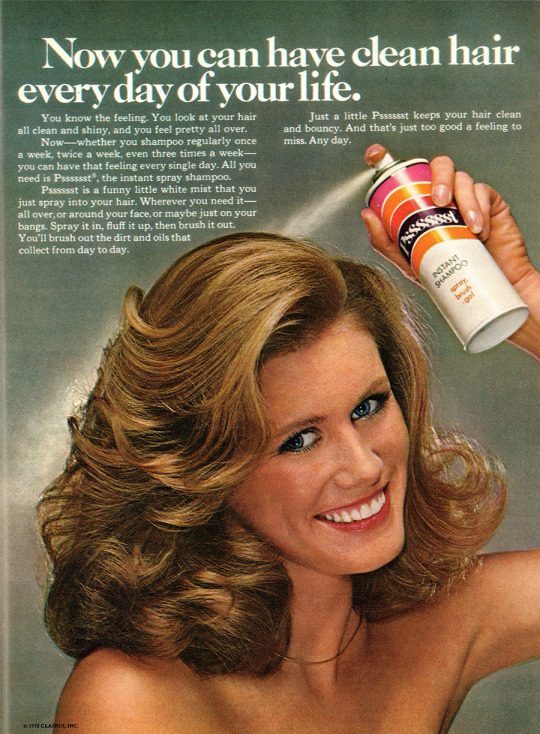

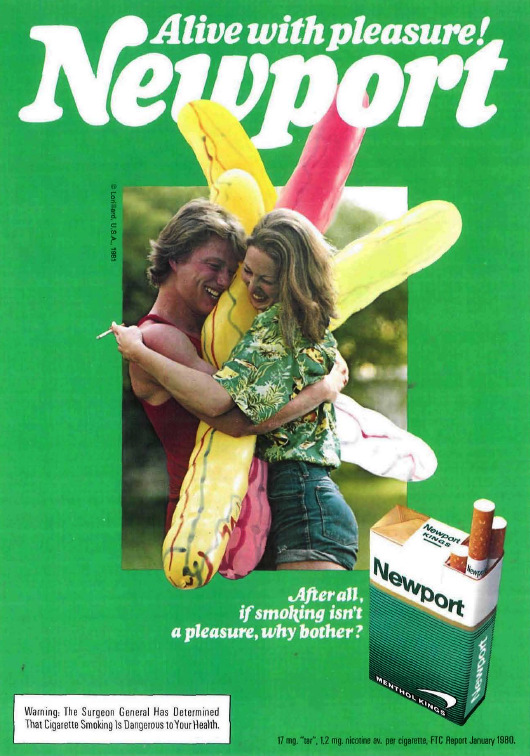

MORE PRINT ADVERTIZING

Remember--period advertizements do not show people as they were, but as the ad firm and client wanted them to be.

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

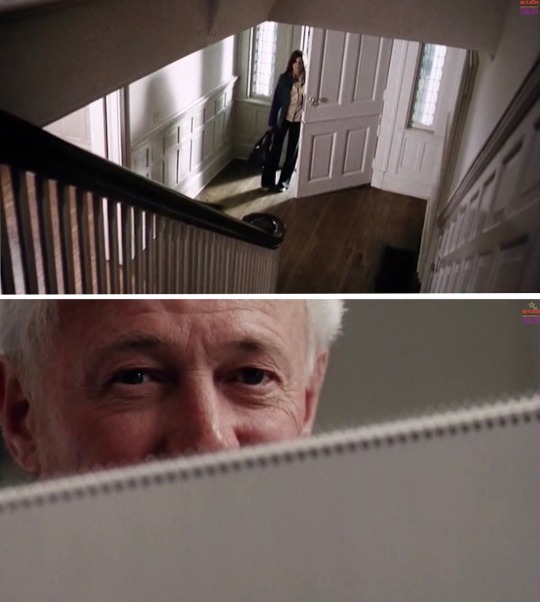

ROBOTS, FEMINISM AND DOMESTIC DYSTOPIA IN CONNECTICUT

"Something strange is happening in the town of Stepford.”

I. Women's Liberation

The year 1972 saw the height of the Women's Liberation Movement in the United States. Earlier that year, the U.S. Congress approved the Equal Rights Amendment (which the states later failed to ratify) and passed Title IX of the Education Act, which banned sex-based discrimination. Gloria Steinem launched Ms. magazine and Helen Reddy's "I Am Woman" reached the #1 position on the Billboard Charts. Ira Levin's novel The Stepford Wives was published at the end of the year.

Levin's heroine, Joanna Eberhart, is the embodiment of the "liberated" woman, aspiring to a career in photography, who reluctantly follows her husband from Manhattan to Stepford, where she encounters the stifling social conventions imposed on women by the patriarchy. Her discovery and futile resistance to the final solution devised by the husbands is implicitly compared to the anti-feminist backlash against Women's Lib witnessed by Levin in his day.

The marketing editor at Random House who wrote the dust jacket summary for The Stepford Wives made a grandiose and highly accurate prediction for the novel's impact on the broader culture: "It is one of those novels whose very title may well become part of our vocabulary. For, after reading it, you will never forget Stepford and the horror it contains; and there is a certain kind of woman who, from now on, will be known as a Stepford Wife." (The prescient editor cannot be faulted for failing to predict that the pervasive cultural influence of The Stepford Wives would owe more to the film version, which continues to attract audiences long after the book has ceased to be read.)

The enduring pop culture icon, the Stepford Wife, is a tongue-in-cheek reification of a the popular perception of the "robotic" perfect housewives who populate bland, wealthy, WASP suburbia. In a broader sense, the Stepford Wife is an emblem of the oppression of white, middle and upper class women by unfulfilling, archaic social roles. Using what amounts to a joke--the empty-headed "robot" wife--to represent a constellation of profound, long-term, social problems without trivializing the issues and thereby offending their victims would probably require authorial forethought, tact and linguistic skill beyond the abilities of a popular fiction writer. Levin's choice to rely on a sardonic metaphor to address a divisive political issue complicated the Stepford project enormously in ways he seems not to have anticipated.

II. "A Very Modern Suspense Story"

The Stepford Wives is, of course, neither a social satire nor a feminist parable, but a thriller. As the publicity for the film stated, it was "a very modern suspense story," an allusion to the very contemporary nature of the subject matter. As for the suspense, one must remember that while Levin may have sympathized with the feminist cause, his primarily goal was to sell books. Rosemary's Baby had amply proven that horror sold very well.

However, the genre conventions of the thriller or horror flic--suspense, macabre situations, gory violence, shocking surprises, the supernatural, monstrous villains--are inherently preposterous and incompatible with serious subject matter. Some might feel that The Exorcist (in which Peter Masterson also appears) used the horror genre to meaningfully addressed a topic of utmost gravity. In reality (pace William Peter Blatty), demonic possession is a portentous fiction, not a serious social issue. The subject of The Exorcist is enhanced, not compromised by a lurid, grand guignol treatment.

Alert to the audience's expectation to be terrified, not edified, Levin (and Goldman) risks diminishing his sbject by having the husbands act like horror movie villains: they subjugate their wives not by ideological indoctrination, but by killing them in a creepy mansion and replacing them with subservient, domestic robots. While the film therefore fulfills its thriller genre requirements, it still shows signs of mixed motivations. For example, Levin felt the need to rationalize the book's far-fetched premise by inserting a pedantic "realistic" explanation for the husband's improbably advanced capabilities in robotics--the group's leader, Diz, was an engineer who participated in the development of the famous 1960s Disneyland animatronics exhibits and shared his know-how with his buddies to solve the urgent problem of keeping women in their place. Horror movie goers would never have demanded a probable explanation, but Levin might have felt that the feminist content required a realistic, rather than fantastic, basis.

III. From Novel to Film

The Stepford Wives producer Edgar Scherick was forced to resolve the project's uneasy blend of controversial political, social satire and horror story. His initial, brilliant solution, was to propose Brian de Palma, as director. Scherick intuited correctly from De Palma's first film Sisters, that the director's personal style could blend social satire, camp and horror. Goldman, however, categorically vetoed De Palma. Scherick then proposed a second, equally insightful solution--the film's complicated generic status and sensitive social content wouid benefit from a the distanced point of view and subtle handling of non-American director. This led to the hiring of respected English director Bryan Forbes.

Forbes, as we shall see, succeeded admirably in creating an intelligent, coherent film, but, given the materials with which he had to work, that film turned out to be a very low-key thriller about a major social issue leavened with a restrained irony. Audiences had no idea what to make of it. Columbia Pictures executives were shocked by the negative response of feminist writers at a press screening of film shortly after its 1975 theatrical release. Betty Friedan denounced it as "a rip-off of the women's movement" and urged women to boycot it. One incensed women's libber broke an umbrella over Forbes' head. Incredibly, the majority of the women present at the event--and many later critics as well--naively assumed that Levin supported the sexist status quo and that the film deliberately parodied or demeaned feminism. Satire proved to be too subtle for the highly partisan subject and the thriller too sensational. The fact that the point of The Stepford Wives so completely missed is a sign of how greatly social and political values have changed since 1975. At the time of the film's release, most viewers, including radical feminists, found the idea of a novel or film sympathetic to women's rights to be unimaginable and/or incomprehensible.

Due to the success of Roman Polanski's film version of Levin's Rosemary's Baby (1968), The Stepford Wives was a hot property. William Goldman, the most successful and sought-after screenwriter in the film industry, acquired the screen rights and wrote a screenplay. Convinced that a non-American would bring a fresh perspective to the heavily-politicized subject matter dealing with core American ideas of social and gender identity, producer Edgar Scherick chose revered British director Bryan Forbes. Scherick's intuition proved right--the director's distance from the subject profoundly altered and improved the film at the level of production details to its broad social themes.

Forbes favored Diane Keaton, who was in the process of repositioning herself as a dramatic actress in the two Godfather films, for the lead role. The actress' analyst, however, disliked the screenplay and dissuaded her client from taking the part (Keaton would explore the negative consequences of Women's Liberation in another thriller, Looking for Mr. Goodbar, in 1977). Forbes then offered it to Jean Seberg and Tuesday Weld. The obvious inappropriateness of both actresses reflected Forbes' lack of familiarity with the rapidly-transforming New Hollywood of the 1970s. Finally, Katherine Ross, lauded for her roles in the cutting-edge blockbusters The Graduate (1967) and Goldman's Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), accepted the part.

Bobbie Markowe, the effervescent, irreverent sidekick to the brooding, serious Joanna, was played by Paula Prentiss, whose can-do attitude, very physical acting style, and skillful comic timing energize much of the central part of the film. When Prentiss carries over aspects of Bobbie's personality into her robot's demeanor, she suspends the science fiction for a moment, giving the viewer a glimpse of a real woman imperfectly adopting to an imposed social role. This easily-missed feature of Prentiss's performance greatly deepens the film's meaning by showing how close Levin's seemingly outlandish concept is to lived reality.

Casting Tina Louise, well-known to Americans as the glamourous Hollywood movie star Ginger in the sitcom Gilligan's Island (1964-67), was another inspired choice. Louise plays Charmaine, a trophy wife who has lately become aware of the downside of being attractive to men. Like career ambitions, the disinclination to serve as the object of male desire is a dangerous view to hold in Stepford, making Charmaine a priority for conversion. The audience's preconception of Louise as the sulty bombshell of male fantasies was so strong, however, that Charmaine's new identity as the Stepford male's idealized beauty seems natural. Due to intangible cultural associations linking Tina Louise, the entertainment industry and the social construction of female beauty, 1970s viewers of The Stepford Wives were likely to regard Charmaine's replacement not as a defeat, but as a comforting return to form.

Forbes was particularly successful in eliciting devilishly clever performances from the minor Stepford Wives. Each actress developed a distinctive persona for her character from at the most 2 or 3 lines. The entire group was then unified by a restrained note of camp. The comic climax of the film is the hijacking of Joanna and Bobbie's "consciousness raising" session by the housewives. The scene, an admirable exercise in deadpan comedy, shows that sensitive feminist introspection cannot compete with a fervent zeal for housecleaning products.

Although the novel and film present a fully-worked out master plan for the continued male oppression of women, The Stepford Wives is the story of its female characters and their plights. This is registered most obviously in the casting of the male characters. With the exceptions of the highly-convincing Peter Masterson, a Goldman friend cast as Joanna’s conflicted husband, Walter, and John Delorean look-alike Patrick O’Neil as Diz, the Stepford husbands are less differentiated, usually appearing in groups, and, in the main, played by such often-seen but rarely-remembered veteran character actors as Franklin Cover.

By Hollywood standards, The Stepford Wives notably lacks major stars. Aware of this, Forbes came to view the actors as an egalitarian ensemble cast with evenly-distributed acting responsibilities. In this very un-American approach to filmmaking, rather than a celebrity's ego, the story is given center stage.

Although Goldman believed he had transformed Levin's novel into a socially-engaged black comedy, Forbes found fault with the screenplay, and partially rewrote it without consulting its author. Forbes' changes improved the film immeasurably. He added the scene of Joanna leaving the empty Manhattan apartment and photographing the man carrying the naked mannekin, which efficiently and vividly provide a sense of Joanna's pre-Stepford life and establishes the chasm that yawns between the city and suburbia.

According to Scherick, Forbes casting of his wife, Nanette Newman, as Carol Van Sant, forced the film's costuming of the wives to be reconceived. Goldman had envisioned the Stepford wives as buxom Playboy bunny types scantily clad in revealing clothing. According to Masterson, Newman "would not have looked good in a Playboy bunny outfit," so the wives were primly-dressed in the long hostess gowns popular in the early '70s and considerably desexualized as well. When one reflects on the costume revision for a moment, it quickly becomes obvious that Forbes was motivated by more than spousal modesty. Both novel and film clearly define Stepford is a decorous WASP enclave governed by traditional manners and ettiquette. In such a context Goldman's racy costumes would have been completely incongruous, injecting an inexplicable lewdness into the film, whereas Forbes's dignified, elegant costumes are infinitely more consistent with the Connecticut setting.

Forbes also greatly toned-down the horror elements of the story, restricting the minimal bloodshed and mayhem called for by the plot for the last quarter of the film. Goldman had written an overwrought, horrific concluding scene of Joanna's murder; Forbes excised it completely, replacing it with a quiet indoor scene where Joanna confronts her own robot replica. This climactic moment, however, shows tell-tale signs of rewriting. When Joanna asks Diz why the husbands are replacing their wives, he replies "because we can." While is grateful that no lengthy anti-feminist speech asserting the need to maintain traditional gender roles is delivered, the explanation given nonetheless seems oddly opaque.

Diz's comment is, in fact, a vestige of a significant dimension of The Stepford Wives which Forbes chose to omit. In the novel, when Bobbie's suspects that "something in the water" changes the wives, she points out to Joanna that Stepford is the home of numerous advanced technology companies, which all the husbands either work for or own. She surmises that this sinister concentration of electronics, computer, animatronics and pharmaceutical R&D has enabled the amoral men to plan and carry out their plan for the permanent subjugation of women.

The dystopian theme of the malign effects of unchecked technological progress on society, a cliché of futuristic and science fiction, is presented by Levin as the novel's ultimate issue. The supression of the women's movement is not what plagues Stepford, it is the advent of complex, new technologies that makes its supression easy and possible. Both sides of the battle of the sexes --the radical feminist determination to destroy the family and marriage and the reactionary male efforts to enforce gender inequality--are symptoms of the general cultural breakdown brought about by the over-rapid scientific and technological transformations (as described in Alvin Toffler's bestseller Future Shock). This theory obviously mitigates the evil intentions and deeds of the husbands.

Forbes establishes this meta-theme when Bobbie explains her theory to Joanna and when Joanna drives past a succession of offices and labs with names like CompuTech and while searching for her daughters. The only other reference occurs when Diz tells Joanna the Stepford plan has been implemented not primarily by the desire to have perfect wives, but because the technology to do so exists. This plot twist so thoroughly diminishes the importance of the feminist content, and renders pointless the careful calibrations of visual effect and calculations of tone developed to present it that one imagines Forbes may have chosen to ignore it as much as possible without alienating Levin and Goldman any further.

IV. The Unity of Visual Style

The Stepford Wives has several inherent structural and thematic contradictions created unintentionally by Levin and Goldman which Forbes could not entirely resolve. He was, however, able to impose a consistency of tone on the material by thoughtful rewriting and by developing a sophisticated production design that unifies the film visually. Although this has yet to be adequately acknowledged, The Stepford Wives is one of the decade's best-looking thrillers. Forbes and cinematographer Owen Roizman (whose truly distinguished credits include The French Connection, The Exorcist, Three Days of the Condor and Network) make great use the widescreen format to create thoughtful, elegant compositions of a type rarely seen in the lowly horror genre. Indoor scenes in particular are framed with great precision by a combination of cropping and the artful arrangement of architectural elements. Views into darker subsidiary and peripheral spaces recall the heavily conceptual representation of interior space in 17th-century Dutch genre painting. These rigorous setups are often shown to the viewer unpopulated or the entrance of a character is delayed a few seconds. In general, shots have strong, linear structures, which are built up into sequences of stately tableaux. One gets the sense that this was the type formal aesthetic Stanley Kubrick attempted to create for Barry Lyndon, but botched by over-inflating the scale and and the over use of static symmetries.

Forbes also avoids brilliantly disregards the clichéd gloomy lighting of thrillers by setting as many scenes as possible in bright, natural daylight. Furthermore, the film was shot entirely on location in and around houses and businesses in Darien, Westport, and Freeport, Connecticut, with no recourse to built sets or harsh, artificial studio lighting. The unfolding of the story's sinister events in a convincingly real natural and consistent visual setting throws the film's more frightening and bizarre elements into high relief. Fans of horror films are tolerant of low production values, which do not interfere with the action (The Night of the Living Dead is far more terrifying because it resembles an unadulterated grainy, home movie). The content of The Stepford Wives demanded, however, a thoughtful visual style, which Forbes and Roizman deliver and which Goldman's treatment entirely lacked.

Forbes ends The Stepford Wives with a serene, balletic coda depicting flawlessly-attired housewives gliding through the local Grand Union Supermarket. This final scene (which borrows from the still, antiseptic aesthetic of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, the visual benchmark for modern cinematic dystopia) is emblematic of the film's intricate balance of genuine creepiness and understated camp. The hushed coda reminds the viewer of the numerous unseen, misogynistic atrocities amounting to a gender genocide implied by the proliferation of Stepford wives. Unnerving as this realization may be, the scene presents it with a thin veneer of camp irony. That provocation vastly complicates our responses to the subject. What aspect of the topic is being undercut by small doses of knowing, corrosive comedy? Is the issue diminished by the distancing effects of satire? Far more disturbing films dealing with the failure of contemporary of social relationships like A Clockwork Orange and The Exorcist studiously steer clear of irony because it is hard to control its valences. The Stepford Wives is still watchable today, in part, because it as willing to take that risk.

V. Legacy

The virtues of The Stepford Wives are more easily perceived through comparisons.

At the time of its 1975 release, The Stepford Wives was considered a disappointing missed opportunity, inferior in every way to the blockbuster Rosemary's Baby. Goldman himself remarked that The Stepford Wives "could have been very strong, but it was rewritten and altered, and I don't think happily." To modern audiences, however, the harsh lighting, obvious sets, hammy character acting, and portentous moralizing (to say nothing of Roman Polanski’s frenetic direction) of Rosemary’s Baby seem forced and archaic, especially when compared to the artful cinematography, naturalism, earnest political engagement, low-key ensemble acting and carefully-limited camp of The Stepford Wives.

If the film was originally misunderstood in the 1970s, it was subsequently misunderstood, dismissed, and, by the turn of the 21st century, patronized. The intricate balance effected by Forbes completely eluded the creators of the unspeakable 2004 remake of the film. Director Frank Oz and screenwriter Paul Rudnick obviously viewed the original strictly as an example of unintentional camp, which they simultaneously sneered at while laboriously attempt to reconstitute at the same time. Turning the original into a pure parody of suburbia--as banal an ambition as one could imagine--required the complete suppression of the all the original film's ambitious socio-political content. The result is a film more lobotomized than the wives it portrays.

The obvious benefits of low-key actors like Ross, Prentiss, Louise, and Masterson become immediately apparent when faced with the gruesome spectacle of egomaniacal superstars Glenn Close, Bette Midler and Nicole Kidman over and underacting, striking poses in hideous costumes, and archly declaiming witless verbiage before a herd of undifferentiated smirking extras. The remake's total refusal to take of Levin/Forbes' intentions seriously, its utterly mainstream hipness, and its unrelenting shallowness are themselves an unintentional form of meta-camp.

The original 1975 trailer can be seen here. The complete film (ad free) may be viewed in the correct screen ratio here.

#the stepford wives#ira levin#william goldman#rosemary's baby#katherine ross#paula prentiss#equal rights amendment#women's liberation movement

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

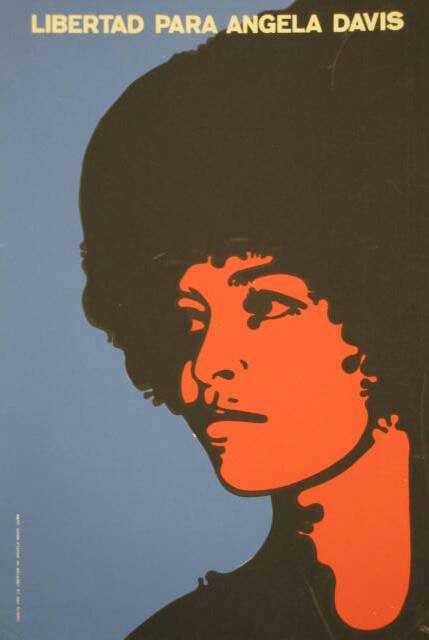

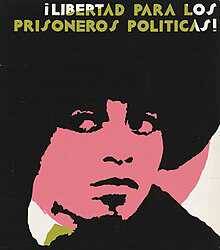

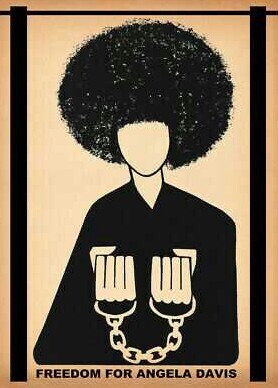

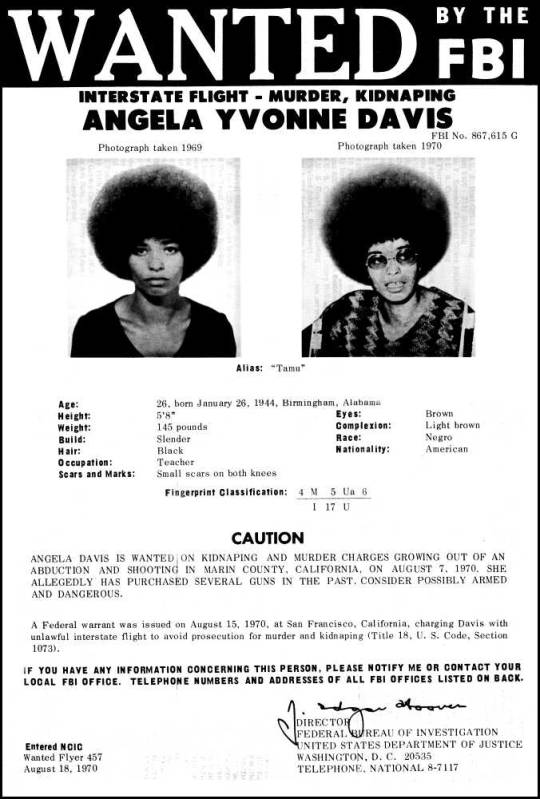

The FBI rushed its Wanted poster for Angela Davis into print within 10 days of her flight from California in 1970. They were, however, completely outclassed by the distinctive graphic design aesthetic of the printed media employed by the movement to free Davis from prison that appeared prior to her trial in 1972.

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Princess Anne meets the Bay City Rollers on Top of the Pops, 1976.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

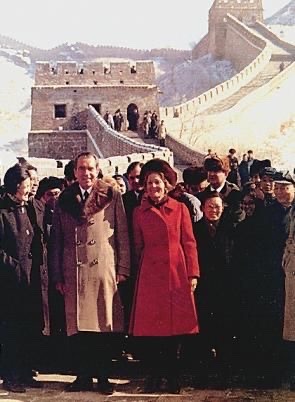

NIXON IN CHINA

President Richard M Nixon visited the People's Republic of China 21-28 February 1972. The trip was intended to begin the process of re-establishing diplomatic relations with China, which had been suspended for the 21 years following the Communist Revolution, led by Mao Tse-Tung, in 1949. The U.S. sought a rapprochement with China as part of its diplomatic strategy to end the Vietnamese War. Nixon was the first U.S. President to visit China.

National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger had gone to China in October, 1971, to establish the agenda, goals and protocols in advance of the President's largely ceremonial visit. Accompanying Nixon were his wife Pat, Kissinger, Secretary of State William Rodgers (who played an insignificant role in Nixon's foriegn policy due to Kissinger's influence), Chief of Staff H. R. Haldeman, Press Secretary Ron Ziegler, speech writer Patrick Buchanan, and his personal secretary, Rosemary Woods.

While in China, Nixon primarily met with Premier Chou En-lai. The president met with Chairman Mao briefly at the beginning of the trip. Nixon also met Mao's wife, Jiang Qing, the wife of Mao and de facto leader of the Cultural Revolution. While in Beijing, the Presidential party visited the Imperial Palace in the Forbidden City and made an excursion to see the Great Wall of China. Mrs. Nixon wore a conspicuously-red woolen coat and red dresses throughout the trip. The Chinese goverment donated two giant pandas to the National Zoo in Washington DC as diplomatic gifts.

At the height of the Watergate scandal, Nixon unexpectedly resigned his office in August 1974. President Gerald R. Ford, traveled to China in December, 1975, where me met with Mao and Premier Deng Xiaoping to continue the process of recognizing China. The formal restablishment of diplomatic ties between the United States and the People's Republic of China took place in 1979, during the presidency of Jimmy Carter.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

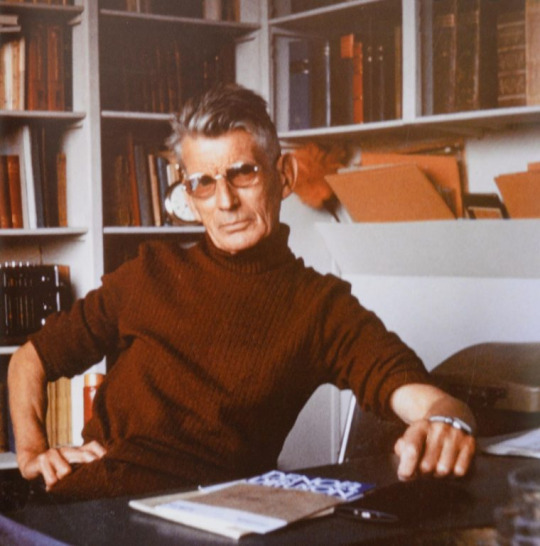

Samuel Beckett, Paris, 1970s.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

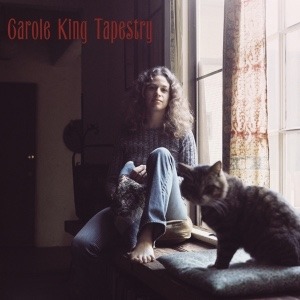

Carole King’s second solo album Tapestry was released 50 years ago on 10 February 1971. The album occupied the #1 spot on the Billboard charts for 15 weeks and remained in the top 200 through 1977.

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

For the complete issue:

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

This excellent live performance at the New Vic in May 1974 captures Joni Mitchell at the height of her artistic powers and commercial success. Backed by Tom Scott and the L.A. Express, the glamourously-attired and madeup Mitchell sails through a more pop-oriented set, including “You Turn Me On I’m a Radio,” “All I Want,” “Big Yellow Taxi,” and 8 of the 11 tracks from her then current release, Court and Spark. The audio and rare color video tracks have been sensitively and skillfully restored, with gaps in the audio filled in with excepts from a radio broadcast of the same concert. Although this recording lacks the professional polish of Miles of Aisles, the performances here are better and the visual component makes up for any period technical limitations.

For more details, see the extensive notes provided by the YouTube source.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Montgomery Ward Catalogue, December 1977; Time Magazine, 5 December 1975; White House Christmas Tree, 1973; Peanuts Plate 1973; First Lady Betty Ford, 1974; Hallmark Christmas Ornament, 1979; Yuletide Disco LP, 1978

5 notes

·

View notes