Lisa Camp Staff Student Advisor - USC Connect University of South Carolina Accra, Ghana Summer 2018 FIDA Recipient Global Partner Program USAC

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

On Choreography

I’d like to reflect in this post on my experience learning African Music and Dance. I should start by saying that “African Music and Dance” might be misnomer for the course I took in Ghana, since I’m pretty sure the three dances we learned were regionally Ghanaian (though potentially dances from various nations located in Ghana). Prior to starting the class, I had a bit of experience with choreographed dancing—dancing that required little to no “connection” to the music and which could be performed strictly on a count (usually 1-8) with or without music. This class was decidedly not the same thing, as it required that we learn what our professor called “the drum language.”

We were introduced to the concept of a drum language in our orientation for the program with USAC when we arrived in Ghana, but no one ever explained what that meant. My experience in my dance class demonstrated that the drum language was something that one should treat like any other language: it requires listening and responding (often critically), which leads to and eventually requires a level of fluency. These dances were not choreographed in the same way I was used to. While there are standard movement sequences associated with specific drum beats, the dance could look different every time it is performed. In fact, though we learned three dances, I know for a fact that they looked different each time we performed them, and this is due specifically to the nature of the drum language and the relationship between the drummers and the dancers.

One of the first things our professor explained to us was that dancers are, to maintain the language metaphor, dually-fluent. What that means is that dancers have to know both the drum beats (our professor, a professional dancer and choreographer, actually drummed during our performance) and the dances. Drummers, on the other hand, are only required to know the drum beats (though it was clear that they knew, visually, what dancers should be doing at any given moment). When we were learning the choreography for each of the dances, the first thing we were asked to do was to verbally repeat a drum beat (for example, gerebeng) and then to learn the movement sequence that went along with that beat (for gerebeng, it was a walking step in which we lifted the right leg in a sort of high-knee style, skipped on the left foot, and swung the right arm in around in sequence with the right leg). We would learn several of these beat/sequence pairs and then we would learn drum cues, which were the beats that told us which sequence to switch to. I’ve been told that this process is similar to “leading” in ballroom dancing, in which the leading dancer performs subtle cues to indicate when something will happen, like a dip. I’ve never learned ballroom dancing before, but I figured the comparison might help.

What I learned from this form of choreography was that I had never really heard or listened to the music I danced to, not really. I hear people all the time talk about “feeling” the music, and as someone who has studied affect theory before, I thought for sure that I knew what that meant. But even when I knew the drum language, I still depended on habits I formed from count-based choreography. One specific habit was common amongst me and my peers, and that was that we expected specific sequences to last for a determined (and finite) amount of time, but the nature of the drum language dictates that you listen to what the drummer is telling you. If, and I quote, “the drummer wants to play that sequence for two hours, then you have to dance to that sequence for two hours.” This distinction between count-based and language-based choreography produces the effect of a “different” dance each time it’s performed. Dancing based on the drum language means that your dance won’t look exactly the same each time, though it will have the same basic components. I’ve included a recorded version of our third dance, Koto je, but I do want to emphasize that even a recording of a dance (an archive?) undercuts the point I’m trying to make, which is that the dance is by nature different every time.

https://youtu.be/bQPF9gH1Ygw

I emphasize this point because it is the nature of storytelling in Ghana (and across African nations) as well. The oral tradition of storytelling is “choreographed” in a manner similar to the dances we learned: there are basic component parts (which can be found in transcribed versions of the stories, like those in Tales of Amadou Koumba translated and transcribed by Birago Diop) which instigate a communal lesson-teaching session. Different parts of the story are meant to provoke questions, comments, responses from the audience, and the storyteller is meant to respond to those. This process produces a different story and storytelling experience every time, and potentially teaches different—if adjacent—lessons.

I say all of this (which is a lot) to say that I think these experiences with African Music and Dance and Literature have taught me a lot about what people mean when they say that you should be teaching the students in front of you. Education—in praxis, in real time—is less about the choreography (which is important in that it keeps you on track for what you want students to learn) and more about how the students respond to that choreography (for instance, whether or not someone might need to rehash something in order to move on, or if a more poignant or imperative topic is weighing on students’ minds at any given moment). I’m not sure I could concretely tell you (yet) how this changes my work and habits, but I know I’ll be giving it all some serious consideration in the future.

I’ve been back for a few days, so next post is all about re-entry! In the meantime, enjoy these photos of my dance class!

~LC

#Study Abroad#Free Range Gamecock#Ghana#African Music and Dance#african literature#Choreography#Dancing

0 notes

Text

Postcolonialism & Sociolinguistics

So this post is a long time coming, but there’s been a flurry of activity over the past week, and a lot of the topics from class have required a lot of reflection. I mentioned colonialism and neocolonialism last post, so this post I’ll focus on post-colonialism as a concept, as the sociolinguistic topics I was interested in when I applied to the FIDA for Ghana derive directly from post-colonialist issues.

Postcolonialism denotes both a political and cultural condition of a former colony (like Ghana and most other African nations) and a theoretical approach in different academic disciplines concerned with the impact of colonization in former colonies. My work in literature hasn’t always included postcolonialist approaches, but it is an academic interest of mine, so being able to study in a postcolonialist state with a postcolonialist scholar (my African Literature professor) has been the best introduction and immersion in postcolonialism that I could have asked for. Relating postcolonialism to the sociolinguistic culture in Ghana wasn’t something I anticipated learning, but it became pretty salient when our literature professor took us to the PAWA House our second week of classes.

PAWA is the Pan-African Writers Association, and when we visited PAWA we met with the president of the association (who is also a local chief, the title for which is Nana). The Association was formed in 1957 alongside Ghana’s independence as the Ghana Association of Writers (GAW) under the conviction that writing was fundamental to the independence effort. This conviction was backed by the country’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah, who was also a writer himself, which meant that the group had strong state support in its early years. While the history of the group itself is much longer and mirrors the country’s political development over time, it is at this point that I’ll deviate from the history to the role of English in African literature (and, by extension, in communicating a uniquely African experience, which is exactly my concern when working with international and post-study abroad students).

During this presentation (an informal question and answer session), our professor and Nana discussed the role of English in African literature, and pointed to Chinua Achebe’s conviction that English is an African language, and that its status as an African language is the price colonizing countries must pay: the colonized will master the language and use it against the colonizer. This perspective on English is related to many other facets of the process of communicating the African experience to others. Specifically, there is an ever-occurring debate on whether African literature should be written in English (or French) or in the author’s mother tongue (e.g., Twi, Fanti, Ewe, etc.) which was the focus of a conference in the ‘60s, which never came to a consensus on the topic. Generally, authors who are in favor of writing in English see it as a means of communicating their experiences outside of their local communities (e.g., in their mother tongues).

We talked further about the use of African English in class, and our professor introduced the use of the language to reflect native thought patterns, which is exactly what I am concerned about in helping students communicate their experiences in English writing back at UofSC. He provided an example, a book of short stories by a Ghanaian author in which English is used to reflect Fanti thought patterns (Fanti being a local nation with its own language). One of the stories, for instance, begins by talking about a woman giving birth via c-section (cesarean), but because Fanti does not have a term for c-sections, the “translation” into English becomes “they cut her open and took the baby out.” If this were written about in a “standard” academic English in the states, it’s likely that an instructor or tutor would direct the student just to say “c-section” or “cesarean” without considering the cultural implications of making such a change. That is to say, this direction to use “c-section” instead of the longer explanation (“they opened her up and took the baby out”) would compromise the student’s native thought patterns (in Fanti) by supplementing native English thought patterns. It’s these small changes that I worry will begin to “shave off” parts of students’ identities, especially those students for whom English is a second or third or fourth, etc., language. While there’s no definitive way to determine how and when to allow a student’s English to be “wrong,” it is something that I would like to be more mindful of in the future.

Finally, I would like to pose a question that was posed to me when I was explaining the debate about African English to a fellow USAC student:

How do native English speakers (colonizers) suffer in any way when English is used to communicate the African experience? What “price” (to use Achebe’s term) do we actually “pay?”

I ask this because it is a question that I don’t have an answer for, and because it is at the center of our motivations for correcting students’ writing in English when it does not reflect native-English thought patterns (like the example above).

No pictures today, but I’ll definitely have some in the next post or two!

~LC

#Study Abroad#Ghana#GLD#GLD Global Learning#Accra#African Literature#postcolonialism#literature#literary theory#English#Africa#Free Range Gamecock

0 notes

Text

My First Full Week in Ghana

Warning: this post is long and gets a little heavy, as some of the topics from class and our tours this past week have been weighty in themselves.

The past few days have been quite a whirlwind, and it’s difficult to know where to start with this post. I’ve definitely waffled between some of the stages of adjusting to the culture, and I think that might be one of the most difficult things about processing my experience abroad. It’s overwhelming when you think about everything you’re having to navigate at any given time:

A new time zone;

Differences in everyday life and habits (e.g., cold showers, instant coffee, remembering to wear sunblock and bug repellants, remembering to take malaria medications, crawling into bed under a mosquito net every night, etc.);

Navigating food choices;

Learning to bargain in the markets;

Learning campus, class schedules, and how to safely move about and interact with locals;

Being flexible and willing to adjust to cultural norms;

New course work on a tight schedule (my midterm in African literature was today, and I have a term paper and a final exam next Wednesday);

Making connections and building relationships with other students in my cohort and our Ghanaian buddies;

Remembering to take care of yourself and not feel bad about resting or craving French fries (which are readily available);

Taking in and learning about Ghanaian culture, infrastructure, and politics.

This isn’t by any means an exhaustive list, but they’re the major things in the back of my mind at any given time. Back home a lot of these things are ingrained in how I live my life every day and I don’t have to think about what my secondary or tertiary choices for dinner are going to be if my first choice isn’t available where I’m eating or which handful of clothes I want to wash because it’ll take a couple of days for them to dry. Ultimately I’ve just been on the go and haven’t had much time to sit and process these things until now, and I know that it’ll take me a lot longer than it takes to write this post to process the majority of my experience. Because of that, I’m realizing how important reflective processes like those embedded in my work advising for GLD are. Even as I’m in the middle of this experience, I’m trying to figure out what I’m going to do with everything I’m seeing, learning, processing, and though I have vague ideas, I don’t have any concrete answers for myself.

On Friday we went on a tour of Accra and visited the W. E. B. Du Bois house where Dr. Du Bois and his family lived before his death, the Kwame Nkrumah Mausoleum where Ghana’s first president is memorialized and interred with his wife, and the Black Star Square where Ghana’s national celebrations are held and where the tomb of the unknown soldiers memorializes those who fought for independence. I’ve posted each of these locations in order below.

We also shopped at an art market on Friday and learned to haggle. I had heard before I left that haggling and bargaining were common practices in Ghana, but it only happens in certain places. Supermarkets and established stores have fixed prices and the Night Market behind our dorm has pretty decent prices when you first ask about them, so there’s no need to bargain there. The art market, however, is a place where haggling is a part of business. It was a little stressful being in the market at first—it’s a mostly enclosed space (think a large grid with stalls on either side of several walkways and a few divisions between groups of stalls to move between them) and it’s hot inside, so that combined with sellers hawking their wares and asking you to come and have a look at their merchandise (and sometimes pulling on you, too) is a lot, especially if you’re not ready for it—but according to our Ghanaian buddies I did a good job bargaining.

The general rule of thumb is to offer a third of the asking price and to settle on something in the middle. For the first thing I bought, the asking price wasn’t easily divided into thirds, so I think I paid a little more than I should have, but our buddies said I got a good price for it. (I’d post a picture of it, but it’s a surprise gift!) My second attempt for a pair of pants went much better and—like I’d been told—I walked away from the seller when we couldn’t settle on a price and was called back to buy them at my price after a couple of turns around the market. The hardest part about bargaining—and the thing our tour guide warned us about—was the impulse to think you’re short changing someone’s work, especially since many of the items are handmade. But the practice of bargaining is ingrained in the business model, as are the offended looks and stories about how precious and laborious the item in question is when you make an offer. I found that being firm and clear and appearing unaffected was the best strategy—a simple “No, thank you” goes a long way in a lot of situations. Thus far I think the market has been my favorite experience because I learned and successfully practiced a new skill.

This weekend we took a trip to the Nzulezu (Nzulezo) stilt village and stayed at the Ankroba Beach Resort. While at Nzulezu our guide reminded us that “we take pictures of structures, not human beings” so I only have one photo of a few of the stilt houses. The village is on a river through two (maybe three?) jungles and because it’s the rainy season it took us about 40 minutes to get there by canoe. Below is a picture of some of our group in one of the canoes. Our tour guides were citizens of the village and the elders gave us a brief history of the village, which houses approximately 7 families.

Ankroba is the place to be if you want to disconnect. It’s quiet, remote, and the water at the beach was surprisingly warm. Below is a picture of a swing (with a few of our cohort) that I took a few turns on with a classmate. There’s a video somewhere of me shouting and laughing, but I haven’t gotten a copy of it yet.

All the while I was reading through Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart for African literature and being confronted with its major themes. In class last week we talked about the conflict between tradition and “modernity,” and as we traveled through the Ghanaian countryside to get from Accra to Ankroba, the juxtaposition between the two became salient for me. The combination of more modern storefronts, completed churches, and the types of buildings you would expect to find in America or Europe (usually tall buildings with lots of glass) with thatch-roofed homes, market stalls, hawkers in the streets, shrines around which roads are built, and the vestiges of western colonialism (mainly in the form of forts and castles that featured heavily in the Trans-Atlantic slave trade and the exploitation of Ghanaian resources) is awe-inspiring. And I would like to make clear that these things are not sectioned off from each other—they all exist in the same spaces, side by side, and in the middle of it all is a massive area filled with technological waste from other countries that is continually burning.

As we toured these places and discussed African literature in class, the topics of colonialism and neocolonialism have come up again and again. Learning about these things in Ghana is much, much different than learning about them in the US. There is no pretense that (neo)colonialist projects are for the benefit of the colonized, and our tour guide and professor do not shy away from discussing the slave trade and the exploitation of Ghana’s resources and people that started with colonialism and are perpetuated by neocolonialism. Being confronted with this history—the history of Ghana from the Ghanaian perspective—means coming to terms with one’s complicity in (neo)colonialist projects.

For instance, that pile of technological waste that takes up acres of land in the middle of Accra? A good chunk of it comes from the United States and it contributes to land, water, and air pollution in the city. Ghanaian resources are still mined illegally by foreign powers and the sediment floods a local river. Etc.

I bring these things up not because I presume to teach others about Ghana with any expertise. They are simply the points that my instructors are asking me to learn and to contend with, and they are the things that are both most poignant to me and the exact things that I am trying to figure out what to do with when I go back home. All of that said, I am having fun and am ecstatic to be learning so much. In my next post, I’ll spend more time on the sociolinguistics of Ghanaian English, as questions of dialect and English are a major point in my African literature class.

#FreeRangeGamecock#Study Abroad#Ghana#African literature#colonialism#neocolonialism#(neo)colonialism#tradition#modernity#Nzulezu#Nzulezo#Ankroba#Chinua Achebe#Things Fall Apart#bargaining#haggling

0 notes

Text

On Showers, Food, and Culture

So when I’m under stress I tend to say, “What day is it?” to signal how frazzled I feel, but it’s never genuine. As I don’t get the summers off of work, I don’t really ever forget what day it is.

Until today.

It turns out that even after a good night’s rest, a 30-ish hour travel session will confuse you, especially if you’re losing and gaining back hours as you go. In the moment that I forgot the date, I knew that I had been traveling for a day and a half and that classes started tomorrow, but my body (and my brain) still said it was Saturday. I think it’s probably because I went to sleep in a bed on Thursday, did some dozing on my last flight (of three) and didn’t go back to sleep until Saturday night, but wasn’t really processing that it was Saturday night. It was more than a little disorienting, but ultimately not quite as shocking as the cold showers.

Yep. You read that right: cold showers. I mentioned in my last post that this was my first experience living in a dorm, and the experience has not disappointed me—I have been shocked and giggled at myself in turns. We learned today about four theoretical phases of transitioning to a new culture: (1) honeymoon, (2) hostility, (3) humor, and (4) home. I’ve heard of these before, and heard the process broken down into more than four steps, and from what I understand there aren’t any “rules” about when people transition from one to the other or how they might bounce around between them. My reaction to discovering that there was no hot water in the communal washroom (two things I’m very not used to: sharing a bathroom and not having hot water) was to check all of the shower stalls to make sure I wasn’t just delirious—which, in my defense, the stalls have both H and C knobs; the H ones just don’t turn unless you’re in the stall where the H and C are in reverse and you think you’ve hit the jackpot when you really haven’t—and then to sigh in exhausted resignation. I’m not sure where that falls on the spectrum of acclimation, but the experience was hilarious in retrospect.

Okay, I thought in the moment, you can do this for three weeks.

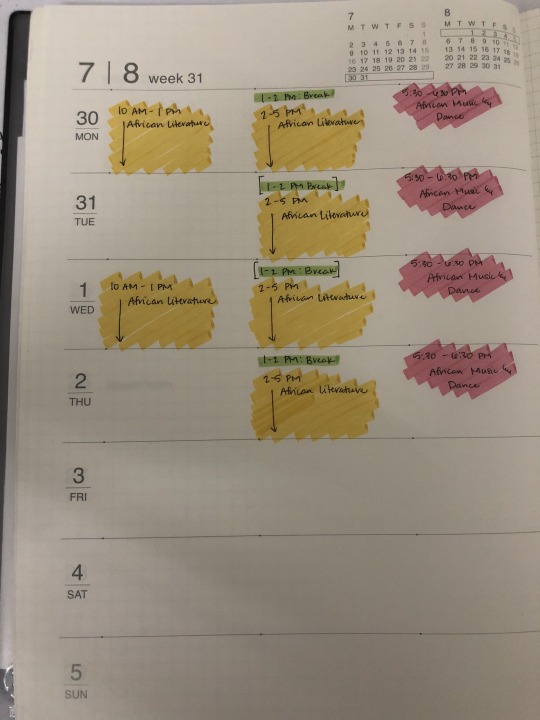

I learned to measure my ability to do things like that—“you can do __ for __”—when I took a weight lifting class. Yeah, it’s 205 pounds, but you only have to do it once. You can do one of anything. I’ve tried to take this approach with a lot of the new and unfamiliar things I’m learning and the intense experiences I’m about to have. For instance, my schedule on Mondays-Thursdays is packed: African Literature for seven (7) hours on Mondays and Wednesdays and four (4) hours on Tuesdays and Thursdays, and African Music and Dance for one (1) hours Monday-Thursday (you can see a week’s schedule below). It’s three weeks. You can do this for three weeks. It’s working so far, but I also realize how unsustainable that thought process is, especially for a longer-term study abroad or living abroad experience, as there are things I’m willingly “sacrificing” (in scare quotes because I don’t think taking cold showers and not using my hair dryer or straightener for three weeks because I forgot to buy a converter are true sacrifices) that I’m not so sure I could let go of for a significantly longer term, which says much more about me than Ghanaian culture and will require more introspection over the rest of my time here.

All of that said, I’m enjoying the things I’m being exposed to. I’ve tried most of the food I’ve been offered so far—I’ve only bypassed something when there was just too much food—and while a couple of things make my mouth feel like it’s on fire (again, because of me; I have a very odd tolerance for spicy foods; some of them I like and others I can’t eat) it’s all been delicious. It’s mostly starch-based cuisine with proteins, potatoes, and plantains (!!!). In thinking about international travel I was always worried that I wouldn’t bring myself to try or wouldn’t like new foods, but I think knowing that there are some foods that are familiar are available and served with other unfamiliar foods (fried potatoes and angel hair pasta are the same no matter where you are) I find it easier to branch out. I learned today, for instance, that I like fried plantains (the last time I tried them in the US I didn’t), jollof rice, waakye (waa-chay), and several other dishes I wasn’t able to learn the names of but know I couldn’t recreate on my own. I think just having good experiences with foods like these will help me frame my approach to trying new foods in the future.

I also learned that being outside doesn’t bother me in Ghana near as much as it does in Columbia. I have pretty rough allergies when I’m in the states, and they’re not gone by any means, but when I walk outside here I feel like I can breathe better than back home. I bring this up because anybody who’s known me for any length of time knows I make a face if people want to eat or just sit outside for a while, especially in the summer. I noticed today that here it doesn’t bother me near as much, and the fresh air actually means something to me. I can’t tell you what that “something” is just yet, but I think it has something to do with all of the open-air architecture on the university’s campus. The International Student housing building and the building that houses the on-site USAC office are these types of buildings: an open structure of rooms that open out to a central courtyard. I’ve posted a picture of the second building (where USAC is) below.

I am also starting to pick up on some of the sociolinguistic differences between Ghanaian and Southeastern-US English, mostly differences in phrasing (for instance what we call “avocados” are “pears” in Ghana, which didn’t seem so strange when I remembered that they’re also called “alligator pears” elsewhere) but I did notice an interesting thing at dinner. After I was finished eating, I offered the rest of my food to another American student—“I can’t eat any more of this. Do you want some of it?”—and thought nothing of it. My parents do it all the time; I offer food to my partner and friends this way; they offer it to me. This classmate had even already established that if we weren’t going to finish something, they might. It was a normal exchange.

Not twenty minutes later I heard another of the American students down the table offer some of their food to one of the Ghanaian students who’ve been showing us around. I didn’t hear the response but did pick up the explanation after. The student explained that in Ghana this type of exchange is rude, and it’s more common to offer an “invitation” to your food at the beginning. They explained that when you share food you’re sharing it: “You eat, they eat, you eat, they eat,” etc. If you want to share your food with someone, you “invite them to your food.” My favorite part of the student’s explanation was that they knew that grammatically “I invite you to my food” wasn’t “correct” but that the phrase encompassed the social aspect of sharing food, which was what made the invitation so important. It occurred to me that the American practice (offering your food after you’ve already eaten what you could or wanted) could be construed as offering “leftovers,” or, to some extent, refuse. I didn’t ask if this was the case, so I’d like to be clear that that’s my speculation and not necessarily what it “means” to offer food this way in Ghana or that it’s the reason doing so is rude, but that little cultural lesson has me thinking differently about how I offer things to other people and the nature of collectivism more generally. It’s the difference between “let’s share food” which makes it “ours” and “would you like some of this food which was mine.”

This was a longer post than I anticipated, but as you can see I’ve had a lot on my mind since I arrived. Classes start tomorrow, so I think an update on academics is in order in a few days!

0 notes

Text

I made an “outline” to pack for this trip. Because I’m that person.

So this week was filled with packing, unpacking, and making decisions about what to bring with me, but I’m 1/3 of the way to Ghana (logistically speaking, not geographically) and very little has gone wrong (so far only a delay from Columbia which didn’t affect my travel times at all). As I reflect on my predeparture process, I think it’s important to note that this particular travel experience features a couple of major firsts: (1) it’s my first international travel experience and (2) (brace for this one) it will be my first experience living in a dorm. So there will be lots of points that I’ll probably make that seasoned travelers and college students will probably go, Hmm, about. Taking these two things into consideration, I was a little frazzled when it came to deciding what to bring, what to leave behind, and what to pack in what bag.

One word of advice from one first-time-international-traveler to another: prepack.

I spent the past few weeks compiling things I knew I would need based on the packing list sent from USAC, and it just seemed like so much stuff. And since I’m a bit of a worrier, I had concerns that my carry on would be too full, or I wouldn’t have room to bring anything back. Ultimately it all came down to the clothes I chose to pack, but I don’t think I would have known that or been as confident predeparture if I hadn’t prepacked.

What I mean by that is that I literally packed all of my bags as if I were leaving—three days in advance. Now that I think back on it, it was kind of like an outline for a paper: I wanted to make sure I included everything important and eliminated anything that wasn’t necessary. Given that’s the exact purpose of an outline, and that I do a ton of writing in my academic field and quite a bit of planning for activities, workshops, etc., in my role with USC Connect, it makes sense that I would approach an uncertain situation that way.

Prepacking (or outlining my packing situation) helped me see what would fit where, and determine what I did and didn’t really need (largely in terms of clothes). Once I was done, I’d actually covered a lot of ground: my checked bag was already packed, and didn’t need to be unpacked; it was ready to go. Books, etc., in my personal item could come out because it’s also my daily bag, so I kept them in a specific place in my apartment so I wouldn’t forget them.

My carry-on was a little trickier. I still needed some of the liquids and hardware from it, so when I confirmed that I had what I needed and that it would fit, I knew I had to pull the Tetris puzzle apart to get a few things back out. And I knew I’d never be able to replicate it. But—like outlines!—I figured I’d take a few snapshots of the “stages” of packing around the items I needed to use. Which led me to my second protip: take pictures of your process. It might not be helpful for everything, but it was a relief when I looked at my bag at 5:45 this morning and thought, Wait. How did I do this? Those pictures saved me a lot of time and stress, and I’m super grateful for that because as someone who tends to worry, it’s always important to have steps for managing what I can control (and, as everyone’s told me, international travel is full of a lot of things you can’t control).

So, even though my first flight was delayed this morning and the barista at this airport Starbucks spelled my name “Louise,” I feel pretty good knowing that what I can control is in order because I tackled packing and planning like I would a paper or workshop for work: with an outline open to negotiation.

I mean, hey, I’ve called my dad’s oldest sister “Aunt Louise” since I was three years old, and that’s not even close to her name, so I feel a little honored to be in the Not-Louise-Louise club today!

#Study Abroad#Predeparture#Packing#Outlines#Literature nerd#Writing#Travel#International Travel#Starbucks#Louise#Ghana#Accra

0 notes

Text

Introduction: Who Am I, Where Am I Going, and Why?

Hey, y’all! Thanks for stopping by to read about my study abroad adventures. My name is Lisa Camp and I am a staff member at USC. I work for USC Connect as an Advisor for Graduation with Leadership Distinction (GLD) and this summer I’m studying abroad in Accra, Ghana, for three weeks! I’m super stoked about the opportunity, as I wasn’t able to study abroad when I was an undergraduate and this particular opportunity was afforded to me by the University Studies Abroad Consortium (USAC) and their generous Faculty International Development Award (FIDA)!

USAC’s FIDA allows faculty and staff to embark on a full study abroad experience by participating as a student in one of USAC’s summer programs. My application for the FIDA focused on my role as an Advisor for GLD, specifically my work with students considering studying abroad, who have returned from study abroad, and with international students who are currently studying abroad at the University of South Carolina. In my application, I selected four potential summer sessions/locations, and ranked them (first choice to fourth choice). Fortunately, USAC not only awarded me the opportunity, but they also gave me the opportunity to study abroad via my first choice—Ghana!

To provide a little background on why I wanted to study abroad in Ghana, I should start with my own academic journey. I majored in English literature as an undergraduate and completed my Master of Arts in English literature at UofSC this past May (May 2018). I’m a medievalist by training, which means that I studied a lot of older English texts—Old English (also known as Anglo-Saxon) and Middle English poetry and prose (think Beowulf-era and Chaucer)—and their cultural contexts. One of the aspects of studying medieval literature that a lot of people I talk to don’t realize is that it’s the study of literature in what would be considered “foreign” languages. While Old and Middle English are technically dialects of English, they are so far removed from the English we speak today that studying them in their original versions (that is, not in translation) requires exercising many of the skills and concepts for learning other foreign languages (I did a lot of translating in my Master’s thesis, and learning Russian at the same time as Old English was particularly helpful because they’re both grammatically gendered languages which decline in similar ways). My interest in studying abroad in Ghana and its relation to my role with USC Connect are connected to the processes, concepts, and skills I learned as a student of medieval literature, which I hope will become more evident as this blog progresses.

As an Advisor for GLD with USC Connect, I advise students who will likely study abroad (in which case I’m often encouraging them to visit the Study Abroad Office on campus to help them learn more about their options for studying abroad—including funding, programs relevant for their majors, and safe locations), students who have studied abroad, and international students who are currently “studying abroad” in the US by nature of their studies at UofSC. These last two groups are the ones that have the most impact on my interest in studying abroad in Ghana for two reasons: (1) I have never studied abroad before (!!!) and would like a better understanding of helping students reflect on their experiences abroad (which happens most often in students’ GLD ePortfolios); and (2) I would like to better understand the experiences of international students who speak English (very well!) but speak a different “dialect” than the “standard” English we often use in academic writing and presenting practices.

Since Ghana’s official language is technically English (surrounded by many other languages and dialects) I intend to pay close attention to my experience speaking the English I grew up with, the English I’m trained in, and how those versions of English differ from the lingua franca of Ghanaian daily life. This particular interest in the differences in English dialects isn’t a simple matter of curiosity or to showcase that I can articulate how they’re different; rather, I’m interested in how language, culture, and identity are connected and how I can better advise students in reflecting on their experiences in ways that are culturally relevant and which do not risk the student’s identity for the sake of dialectic “correctness.” Being attuned to the student’s identity and its relation to their linguistic expression is particularly important for helping them articulate experiences which may not “translate” so well into “standard” academic English. Embarking on this study abroad experience myself is the first step in changing the way I think about helping students reflect on their experiences and how their linguistic cultures play a central role in the reflection process.

While I’m in Ghana I’ll be studying at the University of Ghana in Accra, the nation’s capital. I’ll be taking classes in African literature and African dance, and I’m extremely excited immerse myself in these two major types of cultural expression. If you’d like to read along with me, I’ll be listening to audiobook versions of Taiye Selasi’s Ghana Must Go and Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing during my travels, and Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart for my African literature class. I’ll try to keep you updated on the reading list for class and will definitely be reflecting on my learning from my literature and dance classes and how they help me understand my experience in Ghana!

More on my travel prep and (loose) expectations for the trip in my next post!

~LC

#Study Abroad#Ghana#Accra#Integrative learning#experiential learning#English literatue#Old English#Middle English#African literature#African culture#medieval literature#advising#Taiye Selasi#Ghana Must Go#Yaa Gyasi#Homegoing#Chinua Achebe#Things Fall Apart#lingustics#language#dialect#English

0 notes