my online moss bed (let's ponder the pebbles and ponds!!)

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

I want to start by saying that I genuinely enjoyed reading what you wrote for this week - the way that you walked through your journey in this course and applied your own meaning to some of the major themes in the course, it felt like we were reflecting together :)

Something that you wrote really stuck out to me: “Going into this course, I would have said that knowledge alone can catalyzed change.”

Your points about how knowledge must be supplemented with emotion and connection, which are inherently very personal and individual, is one of the big things I also took away from these past few months. Not everyone has the desire or even the opportunities to be immersed in the intricate details and the “science” of it all – and that’s okay! Nature shows up in different ways in every person’s life, but it shows up for us all. Being able to integrate the knowledge into something less technical, something more akin to the multi-faceted human experience of nature, is a skill – a muscle that interpreters must exercise. In a sort of unexpected way, this course has shifted some of my focus internally, back to people. Instead of thinking only about the backdrop or the environment, which I think we often do in the classroom, I found myself thinking a lot more about those unseen ties between people and nature.

Your next step at UBC sounds like such an exciting one, and it’s a path I’ve not heard many others talk about. Thank you for sharing that! It’s so cool to hear about what peers are doing, especially when it’s something on the more unfamiliar side.

Unit 10: Personal Ethic in Nature Interpretation

Describe your personal ethic as you develop as a nature interpreter. What beliefs do you bring? What responsibilities do you have? What approaches are most suitable for you as an individual?

As I develop as a nature interpreter, my personal ethic has evolved. The beliefs I bring, the responsibilities I have, and my personal approaches have certainly been shaped after nearly completing this course.

My personal ethic is rooted in wanting to inspire people to act pro-environmentally. I’ve always known that my purpose is to motivate change toward sustainability. I wish to encourage others to foster a relationship with nature and value it for its innate worth, as I do. I strongly believe that shaping values and attitudes toward nature care, compassion and connection will encourage sustainable practices and facilitate this necessary societal-wide change.

As I graduate from my undergrad and begin my master's at UBC (where I will study K-12 school children’s understanding of and connection to the climate crisis), I will remember important lessons from this course. For one, through ENVS3000, I have learned that knowledge and emotion are powerful tools for promoting personal growth and inspiring action. According to the textbook, a prime objective of a nature interpreter is to “provoke the discovery of personal meaning and forge personal connections with things, places, people and concepts.” (Beck et al., 2018, p. 6). As I develop as a nature interpreter, I will remember that interpretation is always personal. Personalizing programs to consider diverse socio-demographic groups or place is key in interpretation.

Going into this course, I would have said that knowledge alone can catalyze change. I now believe that knowledge can only take you so far — emotion and connection are key motivators in fostering the development of environmental stewards. But there are other moderators to consider in promoting this change — such as the role of privilege, past experiences and learning styles.

I have learned that privilege (i.e., an inherent advantage that exists for particular people or groups) plays a significant role in shaping individuals’ experiences of nature (Beck et al., 2018, p. 132). As explained in Chapter 7 of the textbook, specific barriers faced by minority/underprivileged groups can discourage participation in interpretive programs. For this reason, underprivileged groups may have fundamentally different experiences with nature (Beck et al., 2018, p. 133). I recognize the role privilege played in my nature experiences. As a city dweller, I gained nature experience due to certain privileges I possess, and conversely, was privileged to have such experiences. My privilege and past experiences play a significant role in my current connection to nature. Therefore, the role of privilege should not be overlooked when formulating and executing interpretive programs.

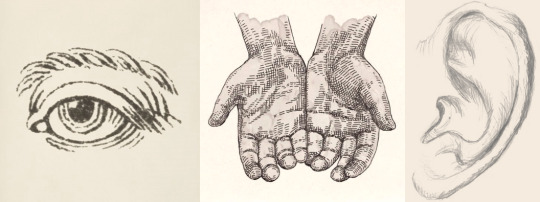

Participants of interpretive programs also possess differential learning styles. In the textbook, we learned that people generally operate within three learning domains — the cognitive domain, the affective domain and the kinesthetic domain (Beck et al., 2018, p. 106). The cognitive domain involves using the rational mind to process information (where intellectual knowledge is held) and interpreters can reach this domain with lecturing or written materials for example (Beck et al., 2018, p. 106). The affective domain relates to learning through feelings and can be reached by expressing attitudes or sentiments (Beck et al., 2018, p. 106). The kinaesthetic domain involves the use of motor skills and can be reached by physical movement or skill development (Beck et al., 2018, p. 106). Employing the use of all three domains will likely enhance the learning experience for all participants. Although there were different learning styles and multiple intelligences communicated in the course content (e.g., verbal, auditory and tactile) (Beck et al., 2018), I felt that the three domains of learning encapsulate what makes interpretive programs stand independent from traditional lecture-style educating … because it is exploratory, active, personal and emotional in addition to intellectual. The learning domains will certainly be a concept I consider in my graduate thesis project.

I hope to one day serve as a model or mentor to others. At the beginning of the course, I read part of the textbook that stuck with me: the principles and associated gifts (Beck et al., 2018, p. 85). The authors defined 15 “gifts” or guiding principles for interpreters, such as the gift of revelation which states that “the purpose of interpretation goes beyond providing information to reveal deeper meanings and truth”, or the gift of beauty which states “interpretation should instil people the ability, and desire, to sense the beauty in their surroundings” (Beck et al., 2018, p. 85). As I grow as an interpreter I will remember these principles and internalize them. I hope I provide these gifts to those I wish to inspire. In my opinion, a strong mentor helps learners uncover deeper meanings and promote personal growth by providing these gifts.

As an individual, I believe a dominant strength of mine is my emotional capacity. I have strong values and morals that guide my intentions and actions. Therefore, I believe my approach to interpretation would emphasize valuing nature and communicating why we should want to protect it. I would take a more personalized approach and help others understand what value nature brings to them by allowing for experiential and exploratory learning.

In a time when socio-ecological issues are worsening, it will become harder to teach children about these issues. I feel the role of environmental grief/anxiety/pessimism will play a large role in the future of interpretation. When the climate has warmed past tipping points, biodiversity loss has reached frightening levels (if they haven’t already) and global conflict increases due to resource scarcity, individuals will feel as if their small actions have minimal purpose or power to create change. Therefore, knowledge surrounding the state of the climate crisis could promote inaction. For this reason, an emotional connection to nature could serve to promote action. We don’t wish to see our loved ones suffer, so if we love and care for nature in the same capacity, this could create the behavioural changes required for sustainability transformations. My personal ethic is rooted in fostering care, compassion and connection to encourage this fundamental transformation.

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage: For A Better World. Sagamore Publishing.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi!!

Reading your post, I found myself in genuine admiration of your devotion to ethical interpretation, conservation, and appreciation of nature.

But it’s also true that I can note differences in what we focused on in our original posts for this week, which points to differences in what we prioritize as far as our beliefs and responsibilities (in a good way!!). Still, I was drawn to respond to your post because of how you also discussed the importance of an interdisciplinary approach to nature interpretation.

I wholeheartedly agree that to understand the complexities of nature, from the governing ecological theories to the more nuanced cultural factors, pulling knowledge from various areas (art, science, history) is not only helpful, but necessary. I also think that this highlights the value in working with other interpreters to round out our own work and the field of nature interpretation as a whole. Whether it means working directly with a team of people of different backgrounds to develop a program or activity, or if it’s simply using your platform to highlight the work of other interpreters, I believe that the end result is more supplemented, richer with experience to be extracted.

I talked about this in several other posts, but I believe in the importance of individuality in interpretation – it allows us to let our unique experience and approaches shine. But by combining that individuality with community, we’re left with a cohesive tapestry, and I think this is one of the main means by which interpretation achieves its interdisciplinary nature.

Thanks for sharing!!

09: My final blog!

As I’m getting ready to graduate soon, ready to hopefully go into the world of science and nature interpretation, I can't help but feel both excitement and a bit of nervousness. Reflecting on my journey through university, I realize that my personal ethic has been quietly evolving, shaped by my deep love for nature and my desire to share its beauty with others!

Since I was a kid, I've been really drawn to the outdoors and nature, especially animals. Whether it was chasing butterflies through meadows, building forts in the woods, or simply lying in the grass and watching clouds drift by, nature has always been one of my happy places. As I grew older, my passion for nature grew more into a passion for conservation and environmental advocacy. I think I started to see nature not just as a playground, but as a precious and fragile ecosystem that needed protection. From the smallest hummingbird to the mightiest lion, every creature and every corner of the natural world has become special to me.

As I prepare to step into the role of a nature interpreter in the future, I find myself thinking about a whole new set of questions and responsibilities. What beliefs do I bring to this work? What kind of interpreter do I want to be? At the heart of my personal ethic, I have a passion for the beauty and complexity of nature. I think that every leaf, every rock, every drop of rain is a masterpiece in its own right, deserving of awe and admiration. But my passion also goes beyond just appreciation, it extends to a determination to protect and preserve the natural world for future generations. In my eyes, being a nature interpreter isn't just about pointing out cool animals and pretty flowers (although those are definitely fun parts of the job). It's about creating a sense of wonder and curiosity, giving people a deep connection to the natural world and inspiring others to become passionate stewards of the earth as well (Beck et al., 2018, p. 42).

To achieve these goals, I'm personally a firm believer in the power of hands-on learning. There's just something magical about getting your hands dirty and your feet wet, about feeling the sun on your face and the wind in your hair. Whether it's leading nature walks, conducting field research, or getting to hold and touch cool animals, I'm all about getting out there and getting involved. I think that hands-on experiences are great at creating a sense of connection (GGI Insights, n.d.). They engage multiple senses, promote direct interaction with the environment, and create memorable, immersive experiences that resonate deeply with people (Bloemendaal, 2023). But hands-on learning isn't just about having fun (although, again, it's definitely a perk). It's also about deepening our understanding of the natural world, bettering our observation skills, and creating a sense of empathy for the creatures we share this planet with (GGI Insights, n.d.). After all, it's hard to care about something you've never seen or experienced firsthand.

In addition to hands-on learning, I'm a big fan of interdisciplinary approaches to nature interpretation. The natural world is truly a complicated place, so understanding it requires more than just a basic knowledge of biology or ecology. It requires us to consider the cultural, historical, and social factors that shape our relationship with nature, as well as the ethical implications of our actions (Spokes, 2020). That's why I think it would be important to always be on the lookout for new ways to weave together different disciplines and perspectives in nature interpretation work. Whether it's incorporating indigenous knowledge into nature walks, exploring the intersection of art and science in outreach programs, or delving into the psychology of conservation behaviour in research, it’s important that we build connections between disciplines (Spokes, 2020). Especially as someone who has a passion for science, discussing science in nature interpretation is crucial because it provides a foundation of understanding, creates informed appreciation, and empowers people to make informed decisions about conservation and environmental stewardship.

Of course, no discussion of nature interpretation would be finished without addressing the elephant in the room: ethical wildlife viewing. As someone who's spent more hours than I can count marvelling at the beauty of wild animals and trying to do wildlife photography, I know how tempting it can be to get up close and personal for that perfect shot. But I also know that our desire for a good photo shouldn't come at the expense of the animals we love. That's why I'm committed to practicing responsible wildlife viewing techniques, like keeping a safe distance, minimizing habitat disturbance, and never feeding or approaching wild animals (Burns, 2017).

Finally, I believe that as a nature interpreter, I have a responsibility to address pressing environmental issues like climate change and habitat loss. These are not just abstract concepts or distant threats, but real problems that are already having a huge impact on the world around us. That's why I'm committed to using my platform as a nature interpreter to raise awareness about these issues, to share stories of resilience and adaptation in the face of environmental change, and to inspire other people to take action in their own lives and communities. Because at the end of the day, it's not enough to simply appreciate the beauty of nature, we have to fight for its protection.

Overall, my personal ethic as a nature interpreter is grounded in a deep passion for the natural world, a commitment to hands-on learning and interdisciplinary approaches, a dedication to ethical wildlife viewing, and a passion for environmental advocacy. As I Start this journey, I know that the road ahead will be long and challenging, but I'm ready to face whatever comes my way with determination, curiosity, and a whole lot of love for nature!

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage: For A Better World (pp. 42). Sagamore Publishing.

Bloemendaal, M. (2023, March 5). Unlocking the Power of Hands-On Learning: Benefits, Activities, and Examples. Studio Why. https://studiowhy.com/unlocking-the-power-of-hands-on-learning-benefits-activities-and-examples/

Burns, G. L. (2017). Ethics and Responsibility in Wildlife Tourism: Lessons from Compassionate Conservation in the Anthropocene. Wildlife Tourism, Environmental Learning and Ethical Encounters, 213-220. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-55574-4_13

Conservation Education: Young People for Environmental Stewardship. (2024, March 8). Gray Group International. Retrieved March 18, 2024, from https://www.graygroupintl.com/blog/conservation-education#:~:text=Hands%2Don%20learning%20and%20outdoor%20experiences%20provide%20learners%20with%20opportunities,sense%20of%20responsibility%20and%20stewardship

Spokes, M. (2020, October 23). The interdisciplinary path to a more diverse conservation movement. Conservation Optimism. https://conservationoptimism.org/the-interdisciplinary-path-to-a-more-diverse-conservation-movement/

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

ENVS*3000 season finale - the sunset post🌤

a sunset pic I took during some sacred cottage time on West Lake near Picton, ON

As the course and the semester come to a close, it feels entirely appropriate that we finish this journey off with some mildly existential thoughts about our ethics as interpreters. I think the fact that I’m also in the process of finishing up my degree has me squirreling out a bit as the cherry on top of this introspection.

While we’ve done a lot of soul-searching over this semester, I think one thing has remained, one thing is evergreen — when I think about nature, I think about serenity, peace, sanctuary. I believe that time in nature has the power and (as fantastical as it sounds) the energy to offer healing. It gives space for a quieter mind, a more peaceful soul. Even as I write these words, the stem student in me is cringing a bit - I have no concrete sources to back up these claims!!

But that points to something invaluable that this course has given me — the leeway to not focus solely on the data and the quantitative and the cold-hard-ness of science, and to instead lean into the interpretation, to focus on the feelings and think about what they mean.

I mean, yeah, I believe in science, I believe in its place, and I love what it’s given me: the knowledge and means with which to explore questions and attain answers. But in interpretation, science can’t stand alone.

I believe in art. Interpretation needs art the same way humans do. Not for some absolutely practical or functional purpose, but for an added layer, added interest, added connection to the natural wonders around us. I believe in the duality of nature and think that the point of interpretation should be to explore that push-and-pull relationship between science and art.

Now as for my responsibilities as an interpreter. I thought a lot about this question early in the course. In the beginning, I think I was intimidated by the idea that everyone must be pleased, must be included. And I know that dismissing the idea that “everyone should be included” can come across as harsh. But I think that I landed on the idea that it’s important to strike a balance between doing everything you can AND “staying in your lane”, as it were.

It’s hard to be everything all at once, and we can’t be. It’s valid to have the desire to accommodate every single person, but what is the cost there? What is the end product once you’ve spread yourself so thin? It doesn't mean giving up, in any sense, but instead highlighting your own abilities and lifting up others who fill in those gaps. It's about the net result, it's about interpretation as a community.

But to be an interpreter inherently puts you in a position of authority, of leadership - and that can be daunting.

So I approach this question a little differently now. Yes, I have the responsibility of providing valuable content to people in a way that respects their stories and their backpacks. I have the responsibility of putting out work that I am proud of, as to not take peoples' attention for granted. But up front, I have a responsibility that harkens back to acknowledging myself, my strengths and individuality as an interpreter.

This line of thought sparked questions not like

“how do I make my content valuable to every person?” or “how do I make sure everyone is happy and accommodated?”

but instead

“what can I realistically provide in a valuable way? which is the audience that will truly benefit from what I can offer, and how can I make sure that I am putting my focus there?”

The answers to these questions are still being sorted out, I think.

Still, I do know that I am more inclined to cater to the artistic- and abstract- inclined. I don’t necessarily see myself on the cold-hard-science side of academia. As a science student, I’ve pushed a passion for art aside in a lot of ways.

And it’s a tad cheesy, I’d admit, but this course has pushed me to think about why that is, and to imagine reintegrating art. Everything is still a little foggy, but there is a semblance of a clear path, or a few of them. Something in the realm of the visual arts, or even an increased focus on less technical writing feels like my fit.

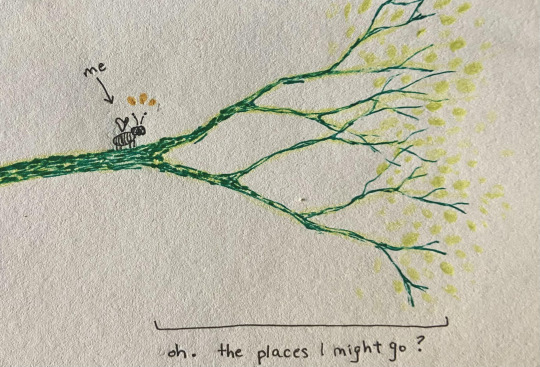

silly little doodle i did

Thinking about how I could approach nature interpretation, I’m brought back to the ideas about learning styles that we touched on earlier in the course. I mulled it over and landed on the fact that I like working alone, and need it to some extent, and I’m coming to terms with the fact that that doesn’t have to be forever. This stage is about self-discovery, for the purposes that I’ve mentioned – offering true value to the audience that would benefit the most. It’s about exploring myself as an interpreter, the things I have to offer, and giving myself time and space to do so.

But I am passionate about the intimate link between people and nature, and I care about sharing this passion with other people. And again, I think that art is a perfect realm for this sort of work. Building community is part of the art world, but so is introspection and individuality. It offers both sides of the coin: time spent alone with the craft, the creation, and time spent sharing what you discovered and made in that time.

While I’d love to have shared some really confident and concrete answers to these questions, I think the best thing I can do right now is be honest about the uncertainty, about the possibilities, and the little bits of self-assuredness that I do hold with me right now, and carrying on this journey of discovery in spite of it.

If you’ve made it this far into this post (by choice or obligation), I really truly want to say THANK YOU. This was a pretty self-centered entry and sharing all these thoughts has been cathartic, to say the least.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

This sounds like such an amazing trip!! There a a couple of things that drew me to your post - your discussion of water and the ocean specifically, and the topic of nature+travel more broadly.

I absolutely understand the hypnotic feeling you hint at. When you say 5 minutes turned into 30, I understand exactly how that goes. Just the other day I was taking a random walk around Eramosa River here in Guelph. There's a little bridge, only wide enough for one-way traffic, in Royal City Park. It was a gloomy day, the kind where the rain comes in gentle but constant spits, dribbling from the clouds like a sprinkler on the lowest setting.

But I found myself on the bridge, looking over its west side towards the dam. Directly downwards, the water pours into an opening that's a little too small to let the water flow through perfectly at the speed it's going. As a result, the water seems to pile up on itself, churning and foaming and twisting before it can make its way through the pass. I ended up standing there, looking over the edge at this mesmerizing sight, for probably a good 10 minutes. In that moment, I didn't have anywhere else to be but there.

And okay, I'm not gonna try to argue that Royal City Park in Guelph, Ontario can face Cascais, Portugal in a fair contest. But still, your post just made me really appreciate how, because of nature, because it is found essentially in every corner of the world, these kinds of experiences can be had all over, by anyone.

And I think that's part of the beauty of travel - it rejuvenates an appreciation for these experiences, because everything feels new and often the whole point is to let go of other worries and preoccupations and to just be in the present moment a bit more, away from our mundane lives back home. Aristotle was ON IT when he said something about leisure being better than work (Beck et al., 2018) - sometimes, we land on interpretation in its purest form when we’re not pining so hard for it.

It gives us some headspace and drive to take in and enjoy everything around us. But it also forms these connections between places across the world and our homes. Tilden noted that interpretation should be recreational (Beck et al., 2018), and the recreation of travel is a way to interpret nature by pulling elements across geographic ranges together. We see the similarities, the stark differences, we miss the sights of home and revel in the novel views of the travel destination. And while this could be said about other aspects of travel, like culture and food and architecture and traffic signs, there's just something special about nature, and especially about the ocean, because it's a little more untouched, unmolded by human hands, while still being so entwined with us.

I sincerely hope that your plans to go back come to fruition!! Thanks for sharing <3

References

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Chapter 3: Values to Individuals and Society. In Interpreting Cultural and Natural Heritage for a Better World (pp. 41-56). Sagamore Publishing.

The most beautiful thing about nature!

What is the most beautiful part of nature? One could argue that it's the glow of bioluminescence, or the way that golden hour lights up the world, or even the flowers growing in your backyard. My favourite part of nature is the ocean. I love the way it shimmers at night, and the feeling of water just submerging your toes.

Recently I had the pleasure of experiencing the ocean for the first time, and I could not get enough of it. In February, I went to Portugal and we did a day trip to a town called Cascais. Cascais is a beach town, and children come after school for an afternoon swim. The first thing we did was visit Boca de Inferno. This translates to “mouth of hell” in English. The ocean is extremely rough in this area, and it brutally crashes against the rocks. It's an ancient cave of eroded limestone cliffs (Cascais, 2024). This was amazing to see, I remember seeing it from a far and then truly seeing it up close. The way the waves crashed along the arches of the cave was beautiful. I kept saying the foam coming from the ocean looked like the fizz on top of coke. 5 minutes turned into 30 and next thing you know we were sitting on the rocks watching the Atlantic ocean crash against us. “Everyone needs beauty as well as bread, places to play in… where nature may heal and cheer and gives strength to body and soul.” This is a quotation by John Muir that describes how nature can reveal beauty and focuses on how nature can even heal people (Beck et al, 2018(21)). I understand this quotation more after experiencing this magical moment. Interpretation is for everyone, and everyone can interpret, whether it's to learn historical and natural features or to try and relate more to the world around you (Beck et al, 2018 (21)). Interpretation is a powerful tool, and I’m glad that when looking back on this memory, I am able to interpret it differently each time.

After this we went to a beach. I was so excited to finally dip my toes into the ocean. The walk there seemed like forever, but it was the best feeling to go up to the water, roll up my pants and stand in the ocean. The rest of the day my friend and I laughed at the seagulls, slept in the sun, made fun objects in the sand and had the best day. I can still picture it perfectly whenever I close my eyes. When I got home I told my parents all about it, which made me almost emotional. Storytelling is a powerful method of interpretation; telling vivid stories can create clear images in the listener's mind, but it can also bring the interpreter back to the moment they're sharing (Beck et al, 2018 (9)).

That whole trip was absolutely amazing, and my friends and I already have plans to go back. But my first time experiencing the ocean will always be my favourite moment from the trip. I will remember the sand, the sun and the water forever. I end this by asking if any of you have had similar experiences with your first time in the ocean?

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage: For A Better World. (Chapter 9). SAGAMORE Publishing.

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage: For A Better World. (Chapter 21). SAGAMORE Publishing.

The best Independent guide to Cascais . The boca do Inferno, Cascais. (2024). https://www.cascais-portugal.com/Attractions/Boca-Inferno-Cascais.html

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

evolution & everything happens for a reason.

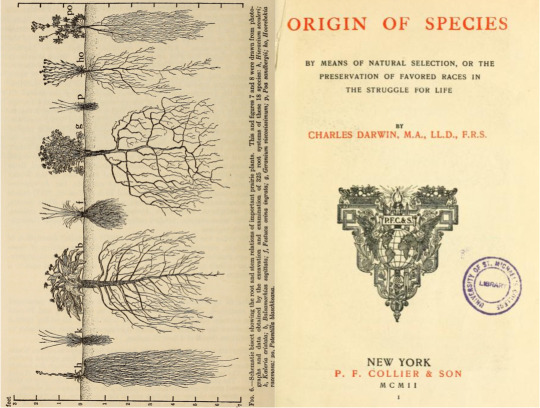

Okay, so pretty much everyone since Darwin has heard about evolution by natural selection. BUT this does nothing to change the fact that it’s still such an interesting and exciting topic!! I’m not going to drone on about the theory of evolution - no, Charles did that for us. Instead, I really want to talk about how having some knowledge of that theory makes my time in nature that much more magical. In this way, I hope to bring the three guiding facets of interpretation together - education, recreation, and inspiration (Beck et al., 2018).

(Side note; I bought a copy of “On the origin of species” when I got accepted to UofG, and still have not managed to make my way through it. No hate to Darwin, but I think we could’ve taken some notes from this class to make that read a bit more engaging - jokes, of course. If any of you have read it in its entirety, I’d love to hear your thoughts…is it worth the read? did he include anything that would be deemed a “hot take” in our modern day?).

In biological studies, we come back to evolution all the time, and we blame it for nearly everything. At this point, I’ve learned the more mechanistic view of evolution, the misconceptions about it, and where we see it in ourselves and the rest of the biological world.

And yeah, makes sense, right?

But for me, it all really clicked last semester in my Animal Behaviour class, which pulled a lot of ideas from economics, cost and benefit, and the prisoner’s dilemma (cue loud groan). I know, I know, booooring.

But honestly, it really put it all into perspective for me – the grandiose concepts of evolution finally had a really solid foundation, such that the story of any natural sight I see is clearer in my mind.

Like, okay, why do parents take care of their young?

Silly question, right? But really think about it for a sec. Well, we know that offspring are genetically related to their parents – if a parent doesn’t take care of their young, the young (and the parent’s genes, and even potentially the act of providing for young) does not persist.

We also know that in some species, one parent (mother or father) puts way more energy into raising the young than the other parent does. Again, why? If they’re both equally related, why isn’t this behaviour equal between the two?

There are a lot of “it depends” here, but one example is that the mother can be 100% sure that those babies are hers, while the father can’t be quite as sure – what if the mama snuck off with another fellow and those kids don’t have any of the “father’s” genes?

Basically, to hedge his bets, the father doesn’t spend his energy on raising young, and instead spends it looking for other potential partners.

who woulda thought that evolution would explain why there's so much drama and gambling in the natural world??

A Friend in Need (1903) by Cassius Marcellus Coolidge

My other favourite example has to do with food caching behaviour in red squirrels vs. grey squirrels. Grey squirrels hide food all over the place, spreading out their cache. Red squirrels make one big stockpile. So, if a grey squirrel defends its caches, it wastes a ton of energy, almost for nothing. It physically couldn’t manage to guard all its nuts at once, so defending one cache leaves an opportunity for other caches to be robbed.

A red squirrel, though, benefits a lot from defending its cache. If it does, it stands a much higher chance of keeping itself fed through the winter, and if it doesn’t, it has lost all of the eggs from its single basket. This explains why red squirrels are the angry little guys they are – they aren’t just evil little devils who’ve escaped from hell. Instead, they just got out of their econ lecture!

Photo: https://www.flickr.com/photos/12144772@N06/1700328393

So, while it might seem that going through the mild pains of learning the theory and its economic/math-y/mechanistic intricacies would make nature as a whole feel less magical, I think it does the exact opposite. I feel like knowing these connections paints a really bright hue on my view of nature. “Why is that thing the way it is?” is such a cool, whimsical question to get caught up in, and I love it.

We've been educated, we've had some fun looking at some silly animal examples, and hopefully there was a hint of inspiration in here too!

Mother Nature really said “everything happens for a reason” and I think that’s super neat.

Anyone else have an "evolution epiphany" moment to share?

References

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Chapter 3: Values to Individuals and Society. In Interpreting Cultural and Natural Heritage for a Better World (pp. 41-56). Sagamore Publishing.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

You describe the intertwining relationship between music and nature so very beautifully. Your emphasis on the point that music likely predates humans, as we find it all over the natural world, prompted a question, for me, about what the actual definition of music is.

I don't know why I hadn't thought very hard about it before, but there is, I think, a definition of music that is absolutely inseparable from nature - that is, all on sides, sourced from and a source of nature. This would be comprised of those natural sounds, rain, wind, thunder, bird and whale songs...

This feels different from the more anthro-centric definition of music, where the sounds come from human-made instruments or computer programs - the ties to nature are of course still there, but I would argue that maybe they're a little looser, a little more abstract.

I loved that you brought up a piece of classical music as the song that brings you immediately to a natural landscape.

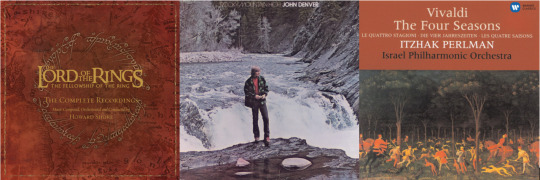

The first songs I thought of when I read that question were The Shire by Howard Shore, of the Lord of the Rings movies, as well as Vivaldi's The Four Seasons (specifically "Winter": Allegro non molto).

In different ways, these instrumental masterpieces paint wonderful landscapes and scenes in my mind, from babbling brooks to wind storms.

I'm not sure what it is about classical / instrumental music that has this effect. Maybe it's the lack of human language getting in the way? A focus on the feeling of nature, instead of an attempt to translate it? In this way, it seems that, for human-made music, it leans toward the "vibe" of natures music.

I loved hearing about how your mom shared this dual nature-music passion with you - she sounds like an effective nature interpreter in her own right!

The memory you shared sounds like a perfect real-life instance of how this type of music makes me feel, so thank you so so much for sharing✨

You Can't Take the Nature out of Music or the Music out of Nature

Music in nature can be found everywhere. It can be defined as instrumental and vocal sounds combined to produce any form of harmony and expression of emotion. By this definition, music in the natural world can be found in anything from the chirping of songbirds to the sound made by leaves rustling in the wind in a certain way. The diversity of musical expression in nature mirrors the rich tapestry of human culture, showcasing an innate connection between all living beings.

Animals and every known culture have a type of music. The undersea melodies of humpback whales, akin in structure to bird and human songs, serve as a testament to the intrinsic musicality ingrained in the animal kingdom (Gray et al., 2001). Despite the vast evolutionary chasm that separates humans from whales, the shared elements of their music hint at a deeper, primordial origin of musical expression. It suggests that music may predate humans, rendering us mere participants in a grand symphony that has been playing since time immemorial (Gray et al., 2001). A birdsong, with its intricate rhythmic patterns and harmonies, also illustrate the profound parallels between human music and the natural world. Each chirp and trill embodies a musicality that resonates with the essence of human composition, showcasing the universal language of melody and rhythm that transcends species boundaries (Gray et al., 2001).

In the natural realm, ambient sounds serve as the backdrop for life's orchestration, comparable to symphony. The cacophony of sounds - from the rustle of leaves to the chirping of crickets - blends harmoniously to create a tapestry of sound that is both complex and sublime. Each creature adds its unique voice to the ensemble, contributing to the rich auditory landscape of our planet.

Amidst the growing prevalence of virtual experiences and digital distractions, an important question is: will technology replace authentic experiences? While virtual tours and immersive simulations offer a glimpse into any hiking trail or natural landscape imaginable, they fall short in comparison to the raw beauty and sensory richness of firsthand experiences. Manufactured goods may lose value over time, but memories and experiences only grow richer with age, enriching our lives in ways that material possessions cannot replicate (Beck et al., 2018).

Experience by Ludovico Einaudi is a song that immediately takes me back to a natural landscape. This is my mom’s favourite song. She grew up on a farm and has lived in Toronto for the past 20 years. Her love for nature never flailed so even in the big city she taught me to stop and appreciate a unique tree trunk or an out-of-place beautiful flower. She says that this song gives her the same feeling as seeing something breathtaking in the natural world- I’ve often seen her get emotional over both. I completely understand why she feels this way. If you’ve never heard it, the piece calmly starts with delicate piano notes and gradually more and more instruments join in creating powerful crescendos. This song reminds me of a specific memory with my mom where she blasted this song while it was pouring rain, we were driving down a road in the middle of nowhere and we saw a rainbow appear as soon as the rain stopped where we could see both ends of it (pictured below).

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage: For A Better World. Sagamore-Venture Publishing.

Gray, P.M., Krause, B., Atema, J., Payne, R., Krumhansl, C., & Baptista, L. (2001). The Music of Nature and the Nature of Music. American Association for the Advancement of Science, 291(5501).

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

nature's sounds & music's roots

I was equal parts apprehensive & elated for this week’s topic — I, like many of us, adore music, and credit it as an irreplaceable source of calm and comfort in my life.

I’m also, of course, part of that big crowd of nature lovers, similarly grateful for the peace that can be tapped into when in the great outdoors.

Thing is, though, the threads that tie these two loves of mine together have been historically frail. Beyond listening to music during a road trip while over-dramatically watching the scenery zip past, or singing along to campfire songs, I don’t know that I’ve consciously linked music and nature together very much during my life.

It feels like, in my life, if they’re found together, then one of the two is taking the back seat.

I’m at a music festival, which happens to be outside, under sunshine and blue skies.

I’m at the cottage, laying in the green grass, and someone happens to be playing a summertime Spotify playlist.

Thinking about it now though, this lack of awareness that I’ve maintained about the link between nature and music is, for lack of a better word, kind of bonkers.

And that’s because music is all over nature, and nature is spread throughout music. The wind rustling the leaves, the waves crashing, our own footsteps in the snow and dry grass and leaves, and, of course, there’s a reason that birders distinguish bird calls and songs. Nature’s music is a subjective, interpreted, spectrum — just as human music is.

some photos by me that (with a touch of imagination) you can *almost* hear

Upon reading the title of this unit, my mind was immediately brought to country music (it’s okay, you can chuckle — I used to be one of those people who’d say “I like pretty much every genre of music, eXcEpT cOuNtRy,” but I think I finally understand and appreciate it’s place🤠).

In this way, I thought the mention in the content for this unit about John Denver was perfect - he’s the epitome of country (and more generally, folk) music’s connection with nature, through the themes of slow, simple days among the fields and trees and sun and streams (see: Mother Nature’s Son, Cool an’ Green an’ Shady, and the Season Suites).

I think the generalization of country music to folk music is notable, here. Virtually every human culture has some vague form of “folk” music, and they often have really interesting similarities, both musically and thematically. These more traditional, cultural forms of music are inherently influenced by nature because they have their ancient roots in times where us humans naturally spent more time outside, relied upon nature for our well-being.

A short clip included in this unit’s content touched on Ocean Mercier’s ideas on the integration of indigenous knowledge into western science (World Economic Forum, 2014).

Ocean talks about how “we have always been scientists” but that our genre of science differs from that of our ancestors. Part of her message is that the values associated with ‘older science’ could prove useful in the aim to reach sustainable science and practices in the modern world.

I think there’s a super interesting link between music’s folk, nature-influenced roots, and old wisdom being unified with modern ideas — appreciating the role of the old in the new, finding the nature in the music.

Shire music makes me feel like I'm sitting in the sunshine, beside a little stream, lazing in the grassy meadows. (Mr. John Denver appears as an honourable mention). Vivaldi's The Four Seasons is all over the place in the best way.

Thank you for tuning in for this one! Wish I had more space to discuss some more of my favourite music with you guys, so if anyone is down to chat about it don't be shy!! As a little prompt, include your three current favourite songs, and for each song, use some nature terms to describe its vibe (could be weather phenomena, colours, seasons, elements, etc.) 💟

References

World Economic Forum. (2014, March 21). Ideas @Davos | Ocean Mercier | Indigenous Knowledge and Western Science [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/SoQS_7yjStE?si=S_-0GeY_AORmlQKX

0 notes

Text

I’m so glad I stumbled across your post this week. The way you linked the first part of the quotation to feeling a sense of connection to our own history and heritage, with the context of the natural world at the helm sparked a lot of interest for me.

I think it’s something like ‘human nature’ to want to know about our family history - yeah, we’re all a little self-centered, probably as a byproduct of our naturally selected brains, and that’s okay. That desire to know about ourselves drives us to better understanding ourselves, and I don’t think that inherently hurts anyone. So, to see nature’s history as our own, to understand that the roots of our family trees go deep, far backwards through time, is a really beautiful thing that you’ve prompted me to think about further (so thank you!). Mostly, I think that understanding the degree to which nature’s history is entangled with our own partly explains why humans find such value in nature. In reality, our tales are one in the same, different aspects of the same story.

I also loved the way you explained the concept of integrity in the context of Hyam’s quotation. I agree that he isn’t necessarily talking about the type of integrity that a lot of us would initially think of - it’s as you said, a strong foundation that unites all that is built upon it, and that allows for the growth to take place at all.

I wholeheartedly agree with your interpretation of the train/train station analogy, where you describe the act of neglecting history as foolish. The word absurd came to my mind when thinking about that part of the quote, so I think we’re on the same page.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m glad he did, but I do wonder what prompted Hyams to specify this, to put this in writing…maybe in defense of the study of history in general? Was he sensing a disregard for history and its interpretation? I’d be interested to hear your thoughts on that pondering.

You write beautifully, by the way. Thanks so much for sharing <3

Embracing Integrity Across Time: The Importance of Ancient Wisdom in a Modern World

During our fast-paced modern lives, it's easy to overlook the significance of ancient things. We often prioritize the shiny and new, dismissing the past as irrelevant or outdated. However, when we pause to reflect on the words of wisdom offered by the quote, "There is no peculiar merit in ancient things, but there is merit in integrity," we begin to realize the importance of maintaining a connection to our history and heritage.

Integrity, as defined in this context, is not just about honesty or moral uprightness; it's about the wholeness and coherence of a system or entity. Just as a building relies on the integrity of its foundation to stand tall, so does our society depend on the integrity of its past to navigate the complexities of the present and future.

Consider the analogy presented in the latter part of the quote: "To think, feel, or act as though the past is done with, is equivalent to believing that a railway station through which our train has just passed only existed for as long as our train was in it." This imagery vividly illustrates the foolishness of neglecting our history. Just as a train station exists before and after our brief passage through it, so does the past exist before and after our brief existence in the timeline of humanity.

Reflecting on my visit last summer, I encountered the relic of the Niagara Falls Power Plant—a testament to human ingenuity amidst nature's might. Here is a video of me exploring this historic site, contemplating the significance of preserving our heritage and honouring ancient wisdom.

In their insightful work on the importance of understanding our place in the natural world, Beck et al. (2018) emphasize the need for stories that anchor us in reality—stories that recount the actual events of our past and illuminate their significance for the present and future. These stories are not mere relics of bygone eras; they are vital threads in the fabric of our collective identity.

Moreover, Beck et al. (2018) underscores the importance of studying our planet's natural history and ecology, recognizing the intrinsic worth of all living beings, and learning from both the successes and failures of human history. By doing so, we gain a deeper understanding of our interconnectedness with the world around us and the impact of our actions on its delicate balance.

In essence, neglecting past lessons disregards the foundation upon which our present reality is built. Each moment in history contributes to the tapestry of human experience, shaping who we are and influencing our future trajectory. By honouring our heritage and embracing the wisdom of ancient times, we uphold the integrity of our collective story and ensure that future generations inherit a world enriched by the depth of its history.

So, the next time you encounter an artifact or relic or stumble upon a forgotten tale from the archives of history, take a moment to pause and reflect. Recognize the intrinsic value of these remnants of the past, for they are not relics to be discarded but treasures to be cherished. In doing so, you'll deepen your connection to human experience and contribute to preserving integrity across time and space.

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage: For A Better World. Sagamore Publishing.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

hopping back on the nature train🚂🌱

If the prompt for this week, a quotation by Edward Hyams, were a food, it would be.. like.. a CLIF bar or something. Small but mighty. So let’s dig in.

Natural history. It’s a legendary tale, a rival to the greatest myths written by the greatest minds. sometimes there’s a hero, a villain, a climax, a happy ending, and sometimes it’s a simpler, meandering story. When interpreting nature through the lens of history, I think it valuable to carve out a foundation, set the scene, tell a story.

This can be a daunting task, especially for science students. From our * formal education *, we’ve learned to separate the fanciful tales from the cold hard facts. We’ve been encouraged to rid our work of human bias. We’re in the training process, the “proving ourselves” process, where cold-hard science is the limiting nutrient. We’ve been instilled with the scientific integrity that forms the backbone of an honest, genuine interest in the natural world.

But that is not how this story should end.

We wouldn’t be doing nature justice to stop there.

Because we’ve also been given the basic tools necessary to start weaving the story back together, after having broken it down, boiled it to bits in beakers. Here, we’re going beyond that, back to real life where humans want to talk to other humans as if they’re humans. And that takes a different kind of integrity: interpretation.

The quotation begins, “There is no particular merit in ancient things”. Nature is an ancient thing, and no, nature is not good or bad — it’s amoral, neutral. Still, I think it’s fair to say that from our humble lil human perspective, nature does have value, and it has meaning.

Hyam continues “…but there is merit in integrity, and integrity entails the keeping together of the parts of any whole.”

I understood this, through the lens of this unit, to mean that integrity, or interpretation, can give “merit-less” nature value and meaning. Nature cradles seeds of meaning that are fertilized, that bloom, when we interpret, when we pull together the parts of the whole into a tale to be told. To have the scissors and glue in hand, poster board in front of you, to collage everything together, is a wonderful responsibility to have, and I think Hyam’s words capture the great power entangled with that responsibility.

image sourced from: https://www.artstation.com/artwork/9NR9ON (artist: Kirsten Harri)

A blade of grass on its own seems so slight, so meager, and honestly kinda boring. But a trained storyteller can weave together all the unseen aspects of that little green miracle. We can come to appreciate how long the evolutionary path has been to have landed at this blade of grass today. Its uses by a wide web of species, by human cultures through time, its love for sunlight and rich soil.

To me, the latter half of the quotation, where Hyam presents his metaphor of the train passing through the station, reflected the vastness and complexities of the timescale of nature’s story. Even more so, the point about the station not only existing for the moments “our train was in it” translates so well into the topic of nature interpretation as a whole. Nature interpretation is not one-dimensional. Nature exists everywhere on our planet (we’ll stick to those confines to simplify this conversation a tad), it exists for so many different people in so many different ways.

So, I agree with Hyam that it is borderline absurd to “think, feel or act as though the past is done with�� — to not profoundly appreciate all the time and work that has gone into the world around us, here and now, to not acknowledge the different cultural dimensions of nature over that timescale. And culture is important here because, well, we interpret for other people in the end.

Really looking forward to hearing everyone else’s thoughts for this one,

Thanks!!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

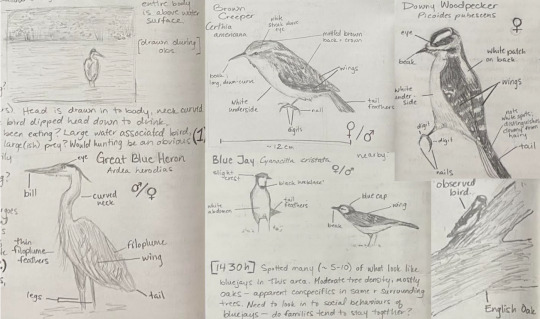

signs in nature🌲🐾

Welcome to this week’s post! For the “free spot” theme of this week, I thought I’d talk a bit about some of the subtle aspects of nature - the hints and clues she gives us about her story as a whole, all while maintaining her exciting traits of mystery and wonder.

I was prompted to choose this topic because of some of the things we’ve been talking about in ZOO 4950 (Lab Studies in Mammalogy). Last week, we bundled up and went out into the Arboretum to talk about tracking. We spotted lots of squirrel tracks, as well as those of a cottontail, a deer, an opossum, and potentially those of a coyote.

left - deer tracks, and a human 👍 ; right - whose little hand do you think this is???

As a little bonus, just to really top it off, we paid a friendly surprise visit to a tree-dwelling porcupine.

photo I took of our porcupine friend in the Arboretum in Guelph

This sparked another sign-oriented conversation, though. We were told about how a porcupine dwelling is simple to spot, essentially because of how nasty these lumbering critters are. Basically, they don’t have a knack for tidying up - they decide on their homestead, which they stay at until it is so overrun with scat that they are forced to relocate. Gross, but also kinda charming, no?

Later in the week, during a little decompressing nature walk by speed river, after a second glance at a tree trunk, I realized I was in beaver territory. there were probably about 3 trees in a 5m radius marked with the teeth etchings of nature’s carpenter.

image sourced from: https://nhgardensolutions.wordpress.com/tag/beaver-damage/

(↑↑↑ real photo credit should go to the artist...a beaver made that!)

These signs may seem like nothing special to someone just passing by. I think it’s fair to say that most people would find it a more special occasion to actually spot one of these critters at work, these these marks and signs. I don’t think I have to do much to convince you all, though, that with a little bit of background information, there’s an entire story to be unraveled.

It can be hard to feel connected to nature in our semi-urban lives, where it seems that most of the things around us - buildings, streets, or (Mother Nature forbid) litter - are exclusively signs of human life.

One tangential point here that I think is really interesting is that nature’s signs are how human beings (and arguably, life across the board) were able to survive in more “rugged” (aka, natural) territories for so long. One of my latest Netflix fixations was a show called Alone, where contestants compete for a cash prize by trying to last the longest alone, in the wild, with only a handful of starting materials. The season I watched took place near Great Slave Lake in the Northwest Territories. The contestants used tracks, scat, even hours of sunlight, to help them find their next meal.

So, if the elusiveness of the animals is getting you down - during your own travels or during a guided walk, for example - you might not actually have to look much further to extract an engaging narrative from your surroundings, or to catch a glimpse into the unravelling nature tale around you.

Thanks for checking in!! 💚💛

1 note

·

View note

Text

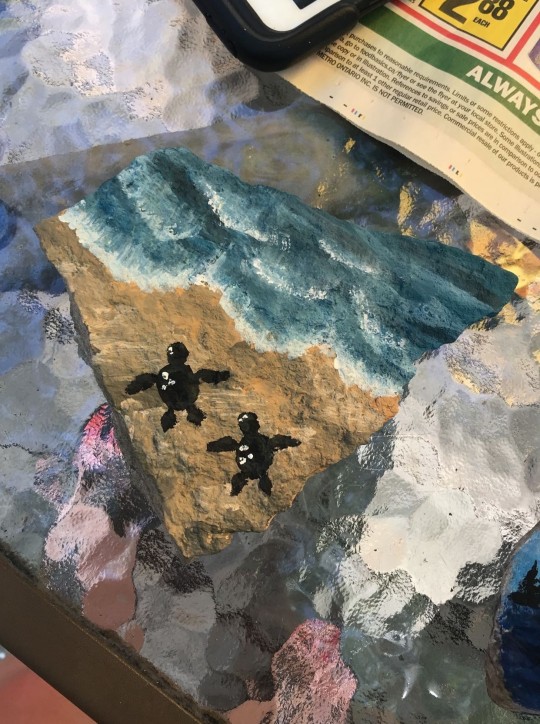

First of all, beautiful rock paintings!! Both technically impressive and super charming :)

I love that you share about the intrinsic inspiration that nature is for so many artists. Your point that art is, in itself, a true form of nature interpretation is one that I wholeheartedly agree with. On that point, it’s likely that for many of us, it’s the first kind of nature interpretation that we actively engage in as kids, which just adds to its wonder and whimsy.

I also really like that you bring up Tilden's idea about how important it is to love both the subject matter that you're interpreting and those to whom you deliver experiences as an interpreter.

I hadn't thought about it in this context in particular, but as soon as I read your connection between loving what you interpret and loving interpretation through art, it clicked; you made it make sense. Your point that one should love what and how they interpret is one that I'm going to tuck into my back pocket - it's such a great guiding principle to have shared.

As for your question about what aligns with me when interpreting nature, I'd like to highlight the other half of Tilden's idea: the audience. I think that I feel most fulfilled when I know I'm providing a valuable service. In interpretation, this translates to making a real connection with the audience, as well as guiding them towards making genuine, personal connections with nature - an idea similar to the way you described the ✨gift of nature✨

I'm a happy clam if I've accomplished that (✿◡‿◡)

Thanks for the question, and thanks for sharing!

Unit 04: Interpreting nature through art and What the "Gift of Beauty" means

This week's unit dives into how we can interpret nature through art. Art is an amazing medium in which we can capture our interpretations of the environment and translate them in a way others can enjoy. As discussed in unit 04, when appreciating a piece of environmental art you're actually looking into a moment in time and the perspective of the artist's world. Being able to share art in all forms allows the viewers to also be present in that moment and experience its beauty. In my opinion, art is greatly about interpretation and it is also found throughout nature within all the amazing things biology has created. With that being said, I believe art and nature are extremely interconnected, as nature is the root of many art forms. The environment does not just exist within art mediums such as carving stones and wood, glass art or ice sculptures, but it is also one of the largest sources of art inspiration. For me, art has always been one of my primary means of interpreting nature. Since I was young, I have felt a strong connection with art whether it was with crafts, drawing, painting or digital art, I enjoyed it all. While making art I often received my creativity from the environment and my favourite types of art are by far landscape or nature paintings. Often, instead of referencing specific locations I enjoy painting my own environments, building a unique natural world for others to interpret and enjoy.

When exploring the textbook readings for this week, we read about the expanded set of 15 principles and associated gifts to help guide interpreters (Beck et al., 2018). Regarding the “gift of beauty”, the text mentions that interpreters can display this by instilling the ability and desire in their audience to see the beauty in their surroundings (Beck et al., 2018). I found this very interesting specifically when looking at Tilden's idea that a love of what you are interpreting and a love for your audience is the overriding principle of interpretation (Beck et al., 2018). When interpreting nature, I find it easy to do this through art because of my prior love for the subject of interpretation. This can allow me to be a stronger interpreter of nature and further connect with my audience through personal forms of expression. I think it is important to reflect on what forms of interpreting nature align with what you love most. With this, we can provide more meaningful and insightful experiences for your audiences. what aligns with you most when interpreting nature?

The gift of beauty to me is how we can share nature through art in a way where others can perceive their own ideas of “beauty”. Allowing for uninterrupted and unique interpretations of nature through art is the true gift of beauty, as it provides diverse views and perspectives. When creating art it allows us to have a special ability to capture and provide an experience of nature to others where they can immerse themselves into the art and create personal interpretations.

References:

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage: For A Better World. SAGAMORE Publishing.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

finding footing in art & nature🦋🌿

This week’s post is about the interpretation of nature through art – I’ll be focusing less on how I interpret nature through art, and more about how I have come to find my footing in doing so.

A quotation from chapter 3 of the textbook (Beck, Cable, & Knudson, 2018) really struck a chord with me for this topic. Talking about studying nature in schools, Burroughs (1916) said that it was:

“Too cold, too special, too mechanical; it is likely to rub the bloom off Nature. It lacks soul and emotion. It misses the accessories of the open air and its exhilarations, the sky, the clouds, the landscape, and the currents of life that pulse everywhere.”

I feel that many of us can relate to this excerpt, as did I. Rub the bloom off Nature.

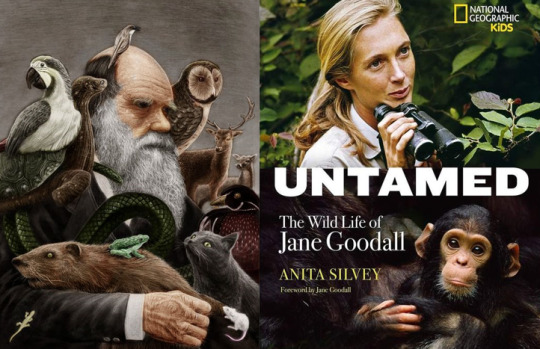

It sounds silly, and I still sometimes feels pretty embarrassed by it, but I really feel like the driving force behind my choice of major (Zoology) was nature documentaries, photography, and Diane Fossey and Jane Goodall’s stories. The images on a TV screen of people out in the wild, so intimately and genuinely immersed in the beauties and intricacies of nature – that is what drove it home for me.

I can’t honestly say that I was thinking - primarily - about learning the ins and outs of statistical methods. Nor was I considering the how-to’s of data acquisition and manipulation, or even hypothesis formulating.

Realistically, I was thinking about how cool it would be to study a major that was defined by natural historians and explorers like Charles Darwin, or the people I saw on Nat Geo programs.

So… who am I to interpret nature through art? I’m someone in a (to some, surprisingly) technical, scientific major. Someone who didn’t necessarily know what they were signing up for, who was (naively) hoping for an experience akin to these creative interpretations. But I’m someone who has come to love these studies because they’ve immensely deepened the connection I’ve always felt to the beauty of nature. When I see a scenic landscape shot or a charming illustration of anything wild, I have so much more in my interpretive toolset than I ever did before. I can parse through the dramatic editing and enhanced colours to find a deeper meaning, one that is simultaneously more informed and more abstract.

The bloom may have been rubbed off a little, but now I can take steps to paint it back on.

Of course, this need not apply to members of the audience. As the hopeful interpreter, I’m fortunate to have this science + art lens, and it is indeed my responsibility to translate that dual perspective into a single, coherent, and cohesive one.

And how do I interpret the gift of beauty? Through that dual perspective.

One of Tilden’s (1957) Principles of Interpretation is that

“the chief aim of interpretation is not instruction, but provocation”

Philosophers have made attempts through millennia to articulate the importance of beauty. One particularly ephemeral type of beauty has been described as “the sublime”. Crudely, it has to do with the almost agonizing appreciation we feel when we see a mountainscape, the ocean, a sprawling forest – something naturally beautiful, perhaps chaotic, immense (notice that most philosophers can’t help but define it in terms of NATURAL beauty).

[ Among the Sierra Nevada, California (1868), Albert Bierstadt. ]

Part of the gift of beauty is in its interpretation; the self-reflection that compels us to ask

why is this sight making me feel this way??? and HOW?

Combining that stand-alone beauty with technical knowledge is a simple step we take after being inexplicably provoked by nature. A step towards appreciating, defining, putting our finger on the gorgeous gift that Mother Nature is, and then making our own creations to try to capture that beauty – kind of like how a painter might study a renowned artist by recreating their work. In this way, we gain some insight into how Mother Nature put all these elements together to make a creation so breathtaking.

---

References

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting Cultural and Natural Heritage for a Better World. Sagamore Publishing.

Burroughs, J. (1916). Under the apple trees. New York, NY: William H. Wise & Co.

Tilden, F. (1957). Interpreting our heritage. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi Joe,

I really appreciate how you emphasized the foundational points about privilege in your post. Mostly I wanted to respond to your post because of the intriguing question you posed about how our education has impacted our ability to interpret nature.

I'm someone whose parents didn't prioritize naturalist-oriented activities. Even in elementary and high school, there wasn't much focus on these topics. I'm fortunate that that has probably been the greatest hurdle in my nature interpretation journey.

Still, I have supportive parents who encouraged me to decide my major for myself. I'm in Zoology, and I know that many other aspiring students out there won't have the chance to follow a similar path. And not because of intellectual capabilities.

Many parents, out of concern and care for their children, might consider this field to be impractical in terms of finding a career that will offer financial stability. Even if the money and the enthusiasm is there, these learners may not be offered the privilege of deciding independently, or will otherwise have to work much harder (emotionally and financially) for it than I and others have.

As you mentioned, this is particularly true for some of us science students. I think it’s especially important that we reach out to our audiences to understand where they’re coming from, as described in this week's reading of the course textbook (Beck, Cable, & Knudson, 2018).

In my own undergrad, we learn a lot about how to simplify things for the so-called “lay audience”. While, of course, we shouldn’t communicate the same with an interpretational hiking group as we do in a lab report, we should actively aim away from being condescending, too. A lot of us haven’t made our way up to this perceived “pedestal” by merit alone, and we shouldn’t act like we have. What I mean is, don't assume! People have all sorts of hidden knowledge to share if you only let them.

Really appreciate that you created space for us to show-and-tell some of our personal backpack contents, and thank you tons for sharing your own.

References

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting Cultural and Natural Heritage for a Better World. Sagamore Publishing.

What role does “privilege” play in nature interpretation?

We’ve definitely discussed some heavy topics in this unit, however, it's important to shed light on these hardships.

For me, I would define privilege very similarly to how it was described with the unit 3 material. I think that privilege means having some sort of advantage over another, in general I typically think this means having an opportunity or obtaining something that's not available to everyone equally. I really like how it was discussed within the unit and referred to as an “invisible backpack” where one can utilize unearned assets that not everyone has access to (Hooykaas, 2024). The idea of these assets being unearned is really important to emphasize, as privilege is certainly something that one can be born into. I think about the example of having a Canadian Passport. I’ve recently done some traveling, going across to the US and even Australia. There are signs at the customs and border crossing lines that divide individuals by the passports that they hold. I’ve noticed that there are lines for Canadian passport holders, along with a few other countries, that have their own essentially accelerated lines. This is interesting to me considering I did absolutely nothing to receive a Canadian passport yet still receive this privileged treatment.

With regards to privilege and how it pertains to nature interpretation, I think we’re all very lucky in Canada to have access to a variety of nature sites and parks. This can be seen specifically when looking at locations such as Guelph. I have access to areas like the Arboretum, Guelph Lake, Speed River, and a variety of hiking trails and forested areas nearby. Additionally, many areas around southern Ontario are like this, and not too far away. Looking at Canada as a whole, there are isolated communities in Northern Canada which might not have the same availability to nature as we have here, and we need to recognize this as a privilege. .

Additionally, when discussing nature interpretation it’s important to recognize the educational aspect that we’re exposed to, specifically as an environmental science student. Because of the different classes and labs I’ve been able to attend, I’ve likely been able to learn more about natural processes and phenomena than the average person. Personally, when I leave the house, I can identify a variety of plant species and fully absorb what's going on around me. I can make connections between what I’m seeing and what I’ve learned in class. This certainly comes with a high degree of privilege as many don’t have the opportunity to learn about these ideas, let alone make connections between what they’re learning and their real lives.

I would love to hear everyone else's thoughts on this! I know I talked a little bit about my experience as an environmental science student, and how being able to apply and observe what I’ve learned in the classroom is a privilege, however I know many of us are in a variety of degrees. For those not in environmental science, how do you think your education has or hasn't impacted your ability to interpret nature?

References

Hooykaas, A. (2024).Hooykaas, A. (2024). ENVS*3000 Nature Interpretation course notes. Retrieved January 23, 2024, from https://courselink.uoguelph.ca/d2l/le/content/858004/viewContent/3640017/View

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

a chat about privilege

This week’s post is about privilege. In all honesty, it’s not easy to define such a loaded and multifaceted concept.

As McIntosh (1989) gave the analogy of the backpack to describe privilege, my own working definition of privilege is that it’s not like the trophy at the end of the race, handed to you while you huff and puff and feel the sweat trickle down your face from all the work you’ve just done. Instead, it’s akin to the trophy already on your bookshelf, with someone else’s (maybe your parent’s) name on it: you still get to admire the view of shining gold, but you never actually earned it, and you may take its superficial beauty for granted. it’s a fixture, one that you wouldn’t think to appreciate unless it was taken from you.

Privilege doesn’t necessarily give you everything, and you won’t always see it upon the silver platter. But it necessarily gives you something, some head start, some cherry on top.

In real life, privilege often manifests, crudely, as not having to worry about x, y, z, as an absence of these invisible barriers.

In interpretation and in general, our privilege is part of us, while also being completely separate from who we are. Privilege shapes who we become, without even consulting us (kinda rude, right?).

It shapes what we know

It shapes how we think

It shapes what we do, what we think we can do

images from Pinterest

But when acknowledged, it can also play a guiding role — through deep reflection we can grab it by the reins and use it as a sort of reminder.

I’ve talked in my previous posts about how I think it’s important to understand yourself so that you can understand what kind of audience you can best serve. But that doesn’t mean only considering like-minded, similarly privileged folks. It doesn’t mean ignoring the problem, it doesn’t mean being lazy.

We can appreciate that our privilege has shaped us and how we see the world, and then we can take that knowledge and expand our perspective.

Our textbook mentioned Pease’s (2015) review about privilege and underserved audiences. Reading this made the issues really tangible, and instantly had me thinking about what I could do to try and reach out to such audiences (and really, it’s not that hard!).

As I mentioned in my last post, my (current) ideal role as an interpreter might look something like developing guided nature journals. it’s unlikely that I can capture every audience in this endeavour, and it is a big feat to try to ensure absolute accessibility to any kind of person.

But we take it a step at a time.

For me, this might entail offering the journal in multiple languages (perhaps having an original English copy translated by fellow interpreters who natively speak those different languages). It could also involve offering the journal as a “pay what you can” product or offering free copies to schools in underserved areas.

image from Pinterest

The related concept of risk and reward was also thought-provoking in terms of my own motives as an interpreter. At this point, I must acknowledge that I’m someone with little experience.

I’m privileged to have grown up with supportive loved ones around me telling me to “just go for it”. But there’s a fine line between taking an opportunity for self growth, without fussing about the consequences, and misleading or taking advantage of an audience for the sake of self discovery.

Thanks for taking the time and stopping by for this one. Everyone’s story is so different and I’m looking forward to hearing them.

---

References:

McIntosh, P. (1989, July/August). White privilege: Unpacking the invisible knapsack. Peace and Freedom, 10-12.

Pease, J. L. (2015). Parks and underserved audiences: An annotated literature review. Journal of Interpretation Research, 20(1),11–56.

0 notes

Text

Hi Alleeya,

I'm so glad I came across your post — you offered a glimpse into your interpretation style and it’s so interesting to note where we overlap and how we differ.

You talked about how your ideal setting would involve interacting with people who share your interest in the material, who care about discussing it, and who can in some way show their interest and understanding.

In some ways, I relate to this very much. In an ideal role, I would hope to be able to take advantage of my passions and strengths such that I aptly offer a valuable experience to like-minded people; people who I can understand in some way, those who I know how to communicate effectively with.

Thing is, our strengths are so different! I would probably be a bit of a disaster in a traditional classroom setting, trying to deliver a lecture to a room of bright-eyed students.

My mind tends to go blank when I’m surrounded by others, trying to deliver information. I’m someone who needs an empty room and a notebook in front of me to create something that makes any sense.

I just think it’s so cool that our ideal roles/settings are similar in their foundational characteristics, all while they differ quite a bit in what the actual details of those roles are.

A challenging conversation with lots of people is not where I would shine, but of course you and many others would. And it’s so important that someone creates a community and a space for those who fall into that category. That’s why I think it’s so important to be aware of you who are as an interpreter — it makes it possible to find your audience, the one that will thoroughly connect with how you interpret, the one that will actually give value to your work.

Reading your post really solidified this idea for me, as you captured your passion so well. Thanks so so much for sharing and best of luck on this journey!!

My role as an interpreter

When first thinking about my ideal role as an environmental interpreter, I pictured the classic 'nature walk' lecture format. Thinking twice, I realized that this is not ideal to me, and instead this is the only version I have formally come to experience.

The more I questioned how I wanted to portray myself as an interpreter, the more I arrived at the same conclusion; a professor. Although this is my career goal, I believe that a professor can very well be considered an environmental interpreter. Having an audience that is interested in the material I am teaching and wanting to ask questions is my ideal setting. I love having conversation that is challenging and engaging. I want to ask my audience questions and watch them piece their knowledge together, I believe this gives the listener a sense of accomplishment and encourages the curiosity required to learn.