Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Like the skull, the candle has been invoked throughout art history as a poignant memento mori, the transience of its flame reflecting the ultimate ephemerality of all life. It is a symbol that is also articulated in world faiths, standing for the ardent strength of the human spirit. Whilst Richter has always considered himself an inveterate atheist and anti-ideologue, the image is a perfect tribute to the man who continues to affirm his belief in art as 'the highest form of hope'. Perhaps significantly, Richter had just turned fifty when he created his first candle painting. At this moment in his life, the motifs of burning candles and gently illuminated skulls were a means to come to terms with the passage of time. As he explained, 'I was fascinated by these motifs, and that [fascination] is also nicely distanced. I felt protected because the motifs are so art-historically charged, and I no longer needed to say that I painted them for myself. The motifs were covered by this styled composition, out-of-focus quality, and perfection. So beautifully painted, they take away the fear' (G. Richter quoted in D. Elger, Gerhard Richter: A Life in Painting, Chicago 2009, p. 262).

christies

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pryde specialised in dark interiors and architectural fantasies.

npg

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reuss' depictions of people has a similarly estranged air about them as those of his objects. Taken out of context, of time, of place, the pictured people appear oddly strange. Melancholic and lonely, but also calm and gentle.

Widdler Gallery

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The subject of the dissection and centre of focus is a common criminal. Rembrandt chose the moment when Dr. Tulp dissected the forearm of the corpse to illustrate the muscle structure. The painting is anatomically incorrect, but Rembrandt focuses instead on displaying psychological intensity. The eager inquisitiveness of the onlookers is striking, as is their proximity to the corpse, given the stench that must have accompanied such dissections.

The staged nature of this painting suggests that public dissections were considered “performances.” There is also a moral message connecting criminality and sin to dissection.

Wendy Osgerby

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hammershøi was painting at a time when interiors were a hugely popular motif. The home was seen as refuge from increasing industrialisation and artists enthusiastically portrayed the concept of hygge in paintings which suggested comfort and warmth. “But you cannot feel that in front of Hammershøi,” says Champion. “It’s absolutely the contrary, it’s very disturbing.” An initial sense of calm often gives way to something more unsettling. They are pictures which certainly call for quiet contemplation even if an initial sense of calm often gives way to something more unsettling. In the sublimely beautiful Sunshine in the Drawing Room III (1903) the delicately observed play of light has an almost meditative quality to it; however its evocation of silence gradually brings on a creeping sense of existential isolation.

Cath Pound

#vilhelm hammershoi#ida reading a letter#sunshine in the drawing room III#interior with the artist's wife ida in their home at strandgade 30#interior of the great hall in lindegaarden

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

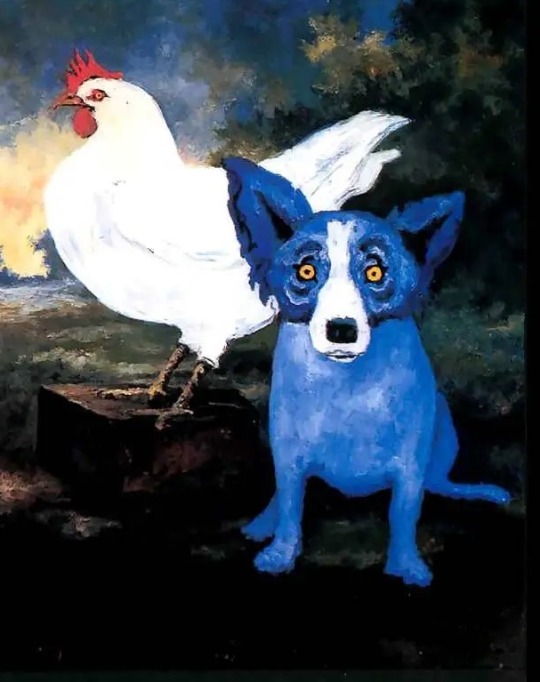

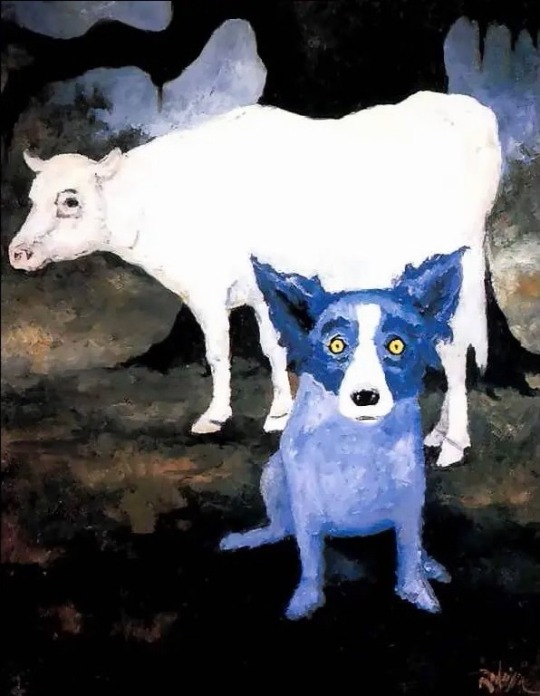

Originally based on the Cajun urban legend of the "loup-garou," or werewolf, Rodrigue found the model for the Blue Dog right in his studio. Inspired by a photograph of his dog, Tiffany, who had just died, created Blue Dog. In reality Tiffany was black and white, but in his imagination her fur became blue and her eyes a haunting yellow. By the early 1990s, Rodrigue dropped the Cajun influences altogether and devoted his full attention to the Blue Dog series. “People who have seen the Blue Dog painting always remember it,” he was quoted as saying. “They are really about life, about mankind searching for answers. The dog never changes position. He just stares at you. And you’re looking at him, looking for some answers, ‘Why are we here?,’ and he’s just looking back at you, wondering the same. The dog doesn’t know. You can see this longing in his eyes, this longing for love, answers.”

artsy

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

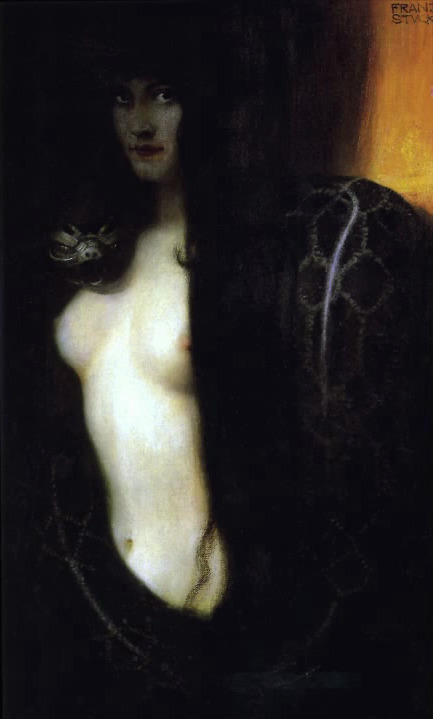

Franz von Stuck (1863-1928) was a leading figure in the Munich art world, both as a secessionist and as an establishment art instructor. Although he painted fairly conventionally when it came to portraits, much of his work can be classified as Symbolist. In his case, symbolism was usually in the form of Classical or Biblical subjects. Stuck's Symbolist paintings tend to be dark, but he made some bright non-portrait paintings along the way, especially around the early 1920s. But he continued his dark Symbolism into the final years of his career.

artcontrarian

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stuck developed the visual idea of representing sin and vice by constricting the format and eliminating the surroundings. Inside the frame, taking up most of the space on the canvas is a standing figure of a woman with a lascivious expression, recognized as Eve. She is visible only to the hips and gazes towards the viewer while a snake wraps around her. There is a highly sharp contrast between Eve’s pale, white skin and the dark, slimy skin of the snake getting ready to bite. In Stuck’s rendition of the First Sin, Eve has already chosen evil and becomes one with the snake: devilish, attractive, and depraved.

thecollector

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A wall of faces greets you in the opening room. Dozens of ink and graphite images look back at us, wonky and misproportioned, but also weirdly right. They’re called Rejects – do their sometimes wild imperfections signal failure, or something else? There are faces everywhere in these rooms of sex and death. Even when she is painting the dead, Dumas’s work is full of life. Near the end of Tate Modern’s Dumas retrospective are her large, oil-painted heads of Saint Lucy, leftwing German militant Ulrike Meinhof and an anonymous young woman shot by Russia’s Alpha anti-terrorism forces in the 2002 Dubrovka theatre siege in Moscow.

On the way, we meet Ingrid Bergman bloated and crying in For Whom the Bells Tolls and Dumas herself looking over her shoulder in a painting whose title, Evil is Banal, nods to Hannah Arendt and her book about Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann.

The Guardian

1 note

·

View note

Text

Because Hodler’s parents died when he was young and many of his siblings succumbed to tuberculosis in quick succession, death became a major theme in his work. His paintings exhibit a sense of mortality and reflections on the cycle of life.

Artsy

In the last decade of the nineteenth century his work evolved to combine influences from several genres including symbolism and art nouveau. In 1890 he completed Night, a work that marked Hodler's turn toward symbolist imagery. When Hodler submitted the painting to the Beaux-Arts exhibition in Geneva in February 1891, the entwined nude figures created a scandal; the mayor deemed the work obscene, and it was withdrawn from the show.

13 notes

·

View notes