Author Pradeep Chintagunta is the Joseph T. and Bernice S. Lewis Distinguished Service Professor of Marketing. His research focuses on the analysis of household purchase behavior, pharmaceutical markets, and technology products. This blog reflects his individual views and opinions.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

How the Amazon and Whole Foods merger will impact other businesses

The Amazon–Whole Foods merger has shaken up the world of supermarkets and supercenters. But it’s also expected to affect and disrupt some other businesses.

These include but are not limited to online restaurant-order-and-delivery businesses (including Grubhub and UberEats), online grocery-delivery businesses (such as Instacart and Shipt), meal-kit subscription services (Blue Apron, HelloFresh, etc.), and more general-purpose delivery services (such as Postmates). With the help of Chicago Booth MBA student Yogesh Kansal, I used Twitter to examine the impact on some of these businesses. We used the same three time frames as when we analyzed the impact of the deal on traditional retailers.

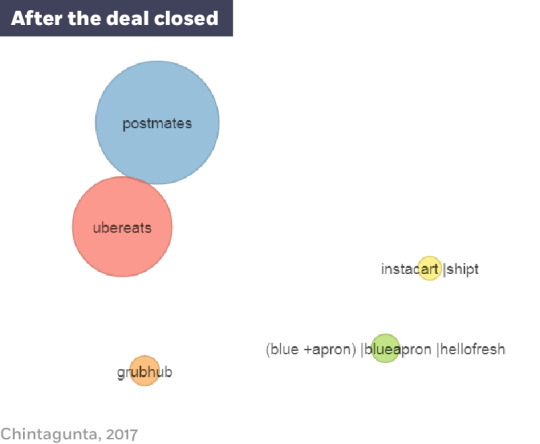

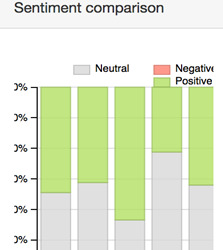

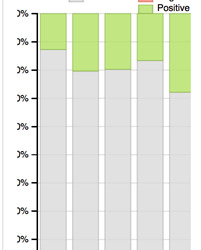

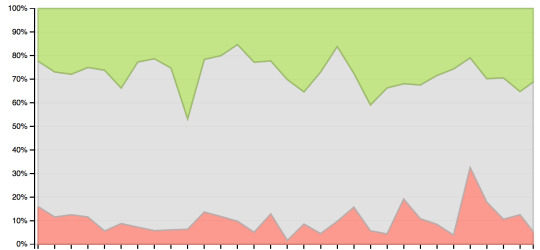

We began with the sentiment scores of the following businesses: Grubhub, UberEats, Instacart and Shipt together, Blue Apron and HelloFresh together, and Postmates.

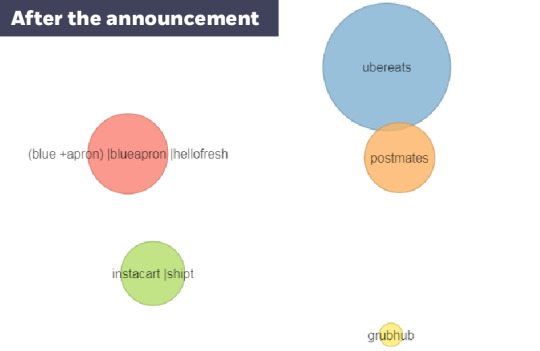

UberEats went from having 50 percent positive sentiment before the announcement to about 60 percent positive sentiment in both periods after the announcement. The same is true for the Instacart-Shipt combination, which also saw a sizable improvement in sentiment. Grubhub initially increased from 28 percent positive to 48 percent positive but slipped back down to just 14 percent positive after the deal closed, with this low figure persisting until September 24. The meal-kit business seemed largely unaffected by the merger announcement, at least on Twitter. But general-purpose delivery may have suffered a bit as well.

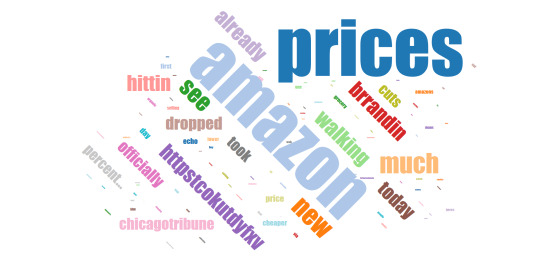

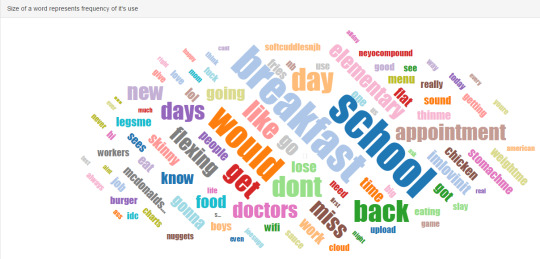

Word clouds indicate that Amazon and Whole Foods figured prominently in the Twitter streams of all the players mentioned, with the exception of UberEats and Postmates, which reflects the more generic nature of these delivery services. While UberEats is itself focused on restaurant delivery, it is part of the larger Uber business, which also includes services such as UberRush, a general-purpose delivery service. The strongest presence for Amazon and Whole Foods registered in Instacart-Shipt, which stems from Instacart’s delivery relationship with Whole Foods. On the other hand, after the merger closed, the only players that saw a continuing presence of the word “Amazon” in their Twitter streams were the meal-kit delivery companies.

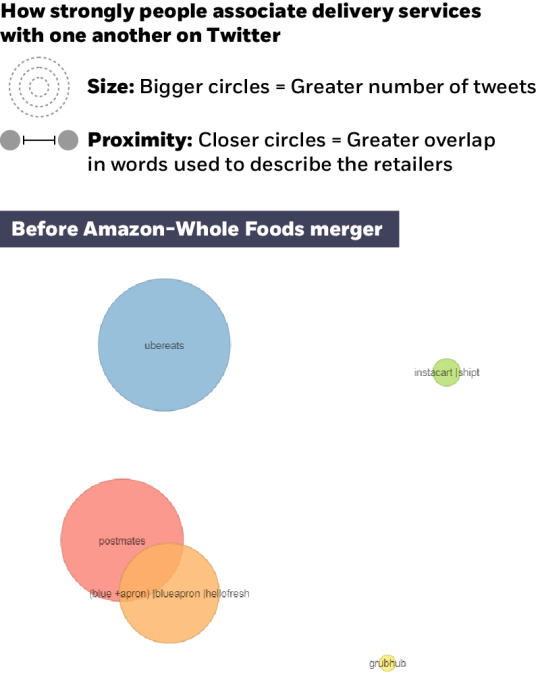

Next, we looked at the perceptual maps of these players to see if relative perceptions were affected by the announcement. We observed a key change in the relative locations of UberEats, Postmates, and Blue Apron–HelloFresh. Prior to the announcement, it appeared, Postmates and the meal-kit delivery services were perceived as having more in common with each other than with UberEats. Postannouncement, however, it seemed that UberEats was viewed as broader than just food, taking it closer to Postmates’ location.

Finally, I looked at feature association maps and saw some consistencies over time in terms of companies and features. Specifically, Instacart-Shipt was associated with the “product” feature (in this case, more specifically with the word “assortment”), whereas Blue Apron–HelloFresh was associated with “price,” and GrubHub with “competition.” By and large, the consistencies seemed to outweigh any marked changes in feature associations, at least over this rather short time interval. A confounding factor to note in this analysis: the time period also involved the initial public offering of Blue Apron, which had a fairly rocky start as a public company.

To the extent that we observed on Twitter, any changes to these businesses seemed limited mostly to the positive sentiment that consumers have for the companies.

Pradeep K. Chintagunta is Joseph T. and Bernice S. Lewis Distinguished Service Professor of Marketing at Chicago Booth. He blogs at kiltscenter.tumblr.com. He thanks Booth MBA student Yogesh Kansal for his feedback and input.

0 notes

Text

How Amazon’s Whole Foods deal impacts supermarkets and supercenters

In the wake of Amazon buying Whole Foods, there has been much hand-wringing by analysts over the fate of supermarkets and supercenters. Clearly, the concern is that the merger will result in lower prices and improved efficiency of operations at Whole Foods, and will combine these prices and efficiencies with delivery, thereby severely impacting traditional supermarkets such as Kroger, as well as supercenters such as Walmart. Indeed, the stock prices of traditional supermarket chains suffered as a consequence of the deal.

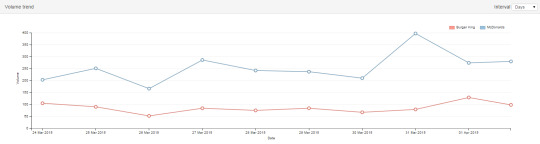

With the help of Chicago Booth MBA student Yogesh Kansal, I looked at audience reaction to the event on Twitter. In particular, we looked at the reaction the week before the June 16, 2017, announcement, the week after, and the week after the deal closed on August 28. Since one would expect an increase in the volume of tweets, we looked instead at other metrics such as sentiment and relative perceptions. For purposes of the analysis, we looked at Kroger, Walmart, and Safeway (as well as, of course, Amazon and Whole Foods). In the wake of Amazon buying Whole Foods, there has been much hand-wringing by analysts over the fate of supermarkets and supercenters. Clearly, the concern is that the merger will result in lower prices and improved efficiency of operations at Whole Foods, and will combine these prices and efficiencies with delivery, thereby severely impacting traditional supermarkets such as Kroger, as well as supercenters such as Walmart. Indeed, the stock prices of traditional supermarket chains suffered as a consequence of the deal.

Sentiment Comparison

From the sentiment figures, we see that the positive sentiment for Amazon ranged from 45 to 50 percent (negative sentiment was 5–8 percent), with positive sentiment slightly rising and negative sentiment slightly dipping right after the announcement. However, in the week after the deal closed, positive sentiment for Whole Foods went up from about 68 percent after the announcement (it suffered a slight dip from 73 percent before the announcement) to 75 percent after the deal closed.

To dig more into possible reasons for the rise in positive sentiment, we looked at word clouds from the three periods for Whole Foods. The price cuts seem to have had some effect. Note that, in this case, the cuts are quite credible, i.e., this was not a case of the company replacing products with lower-quality items. Hence the perception of value was enhanced, leading to a more positive sentiment.

Before announcement

After announcement

At deal closing

So how did the other supermarkets fare in the eyes of the Twitterati? While the sentiment for Walmart does not seem to have been affected much, both Kroger and Safeway showed a change. In particular, Safeway saw a large drop in positive sentiment, from over 50 percent to just a bit over 20 percent. However, according to data examined over longer time periods—from May 1 to May 31 and from September 1 to September 24—the positive sentiment level for Safeway was between 25 and 30 percent, suggesting that there were idiosyncratic factors (combined with a relatively low tweet volume) that contributed to the high positive sentiment between June 9 and 15.

Kroger, on the other hand, does seem to have seen a drop in positive sentiment from the low to mid-30s, again verified by looking at data from May 1, to the low to mid-20s right up to September 24. However, here as well there is the confounding factor of Hurricane Harvey, at least for the latter part of August, although this would not necessarily explain the stable September numbers.

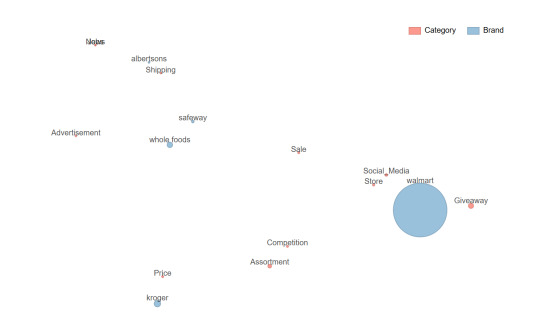

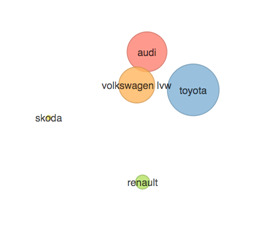

Next, we looked at the relative perceptions of the retailers over time. As mentioned in previous CBR essays (such as “As Sears fails, who will buy its brands?” Summer 2017), these maps are constructed from similarity metrics constructed between each retail pair. The similarity metrics are obtained from looking at the overlap in words used on Twitter to describe the retailer in each time period considered. The size of the circles represents the volume of tweets associated with that retailer. The maps below suggest that Twitter users’ perceptions of the retailers only changed in the short run and, by the time the merger closed, had reverted back to what they had been before the announcement. So at least in the immediate aftermath, we do not see any fundamental changes in perceptions of the various retailers.

Relative perceptions

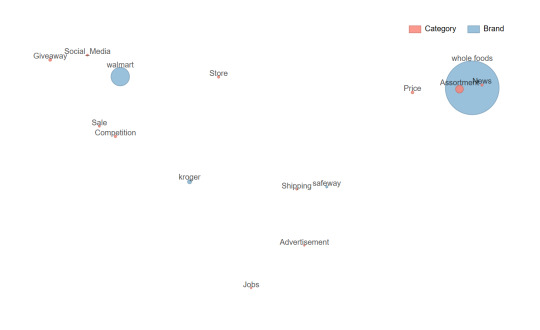

In the last piece of analysis, we looked at the topics associated with the tweets for each of the retailers in each of the three time periods. There are several noteworthy points to glean from the pictures. The first is that Walmart and Whole Foods were generally located at opposite ends of the spectrum in each time period. Walmart was associated with social media, giveaways, and its stores. Whole Foods, on the other hand, was associated with several features but not strongly pegged to any of them.

After the announcement, however, we see a marked change. While Whole Foods and Walmart were still viewed as “opposites,” the former showed a strong association with price and assortment, whereas Walmart’s main features continued to be its stores, giveaways, and social media. Finally, after the merger closed, Whole Foods retained its association with price, largely because of the price cuts instituted by Amazon. Assortment shifted back toward Walmart and appeared equidistant to both retailers. Thus it seems Amazon was able to clearly highlight the impact it was having or planning to have on prices at Whole Foods.

Another observation from these maps is that, by and large, Albertsons and Safeway stores, which share the same ownership umbrella, had reasonably proximal locations on all maps. At least from a positioning perspective, this is good news for these retailers in terms of projecting a uniform image to consumers.

Brand feature associations Before announcement

After announcement

At deal closing

To summarize, the data seem to reveal some short-term changes in sentiments, perceptions, and associations for these top retailers. Whether these changes can be sustained over time, and whether they prove more or less successful for the retailers, remains to be seen.

Pradeep K. Chintagunta is Joseph T. and Bernice S. Lewis Distinguished Service Professor of Marketing at Chicago Booth. He blogs at kiltscenter.tumblr.com. He thanks Booth MBA student Yogesh Kansal for his feedback and input.

0 notes

Text

With Whole Foods, can Amazon fill your every need?

It’s trying, by embracing scope, scale, and speed

Amazon’s recent acquisition of Whole Foods has triggered a lot of discussion about the motives behind the purchase. But many of these explanations can be rationalized by looking at Amazon’s primary mission, which says, “At Amazon, we are committed to being the most customer-centric company on earth.” That is not only a rather audacious statement; indeed, it is a tall order. And while some people may in the past have perceived the mission statement as purely aspirational, over time, with moves such as this acquisition, it is increasingly clear that Amazon is trying to make what seemed aspiration into a reality.

One way in which marketers often approach customer analysis is by studying what has been referred to as the customer’s “journey,” or the “consumption chain.” Essentially, studying this journey includes mapping the steps that a customer goes through when fulfilling a specific need, then trying to make sure that your company’s product can fulfill that need.

For example, let’s say a customer needs to wash clothes. With the consumption chain in mind, one can trace a number of innovations that detergent manufacturers have incorporated into their products over time. One step in the customer’s journey is knowing when it is time to buy more detergent. Accordingly, manufacturers introduced transparent “windows” in containers of liquid detergent so consumers could gauge when they were running low. Another step is the act of pouring the detergent. To help customers avoid making a mess on the side of the container or dripping detergent on the floor, manufacturers added spouts designed to ease pouring, as well as channels to allow excess detergent to drip back into the bottle. (Manufacturers are more reluctant to add clearer markings than they currently do on the insides of caps that would help customers measure detergent according to the size of their loads, since they would rather customers use more detergent than required.)

Amazon has taken the idea of mapping the customer’s journey beyond merely fulfilling a specific need to trying to address all the needs a customer might have over the course of a day. In many instances, this goal involves providing services that complete the need-fulfillment journey for specific categories. In the detergent example, after a customer recognizes that he needs to buy detergent, he still needs to go to the store, pick the product from the shelf, pay for it, come home, and use it. Amazon is able to help a customer complete nearly all of these steps through Amazon Prime Now, a single service that delivers products within two hours of an order.

But Amazon has gone beyond even this by creating ways to make the process simpler. The first is the Amazon Dash Button, a physical button that customers press when they need a specific product. If you’re running low on Tide detergent, press the Tide Dash Button that you’ve affixed to your washing machine to order more. However, while Dash buttons solved a specific problem, Amazon also created the Echo speaker, which takes voice commands. Echo obviates the need for multiple Dash buttons while also offering other, unrelated services, including the ability to control devices such as alarms and radios.

A customer’s daily activities include more than washing clothes, of course they also include waking up, eating breakfast, taking a shower, getting dressed, going to work, returning from work, relaxing in front of the television, preparing dinner, and going to bed. It is not hard to see how, over time, Amazon has increasingly crept into these activities—by delivering groceries for breakfast, toiletries to use in the bathroom, clothes to wear, television and content to enjoy while relaxing, and more groceries as well as other food delivery for dinner. The inexorable moves to map and fill a customer’s daily needs mean that Amazon is becoming increasingly central to the consumer’s experience, as much as it is becoming more customer-centric in everything it does. This idea of occupying “adjacencies”—meeting customer needs proximal to those that you currently fulfill—has been a pillar of marketing practice for a long time. Amazon, for its part, has done this aggressively and expansively, by meeting a core or “primitive” need first, and then layering on top of this need to meet additional needs over time.

Scope, scale, and speed To be more customer-centric, Amazon has clearly recognized the power of the three s’s: scope, scale, and speed. In order to become the one-stop destination for the consumer, what Amazon really needs is scope. The more products and services that consumers can find under one roof, and the more easily consumers can access these services, the more benefits consumers will see and accrue by engaging with Amazon.

But customers will not be attracted to Amazon if they find prices too high, which is where scale and efficiency come in. Having access to a very large customer base allows Amazon to obtain favorable terms from suppliers, while having efficient operations keeps a further lid on costs.

And then there is speed. One-stop, lowcost shopping is certainly attractive, but if a customer’s need is not immediately met, the shopping experience will not be fulfilling. This is where speed comes in: having more locations conveniently located close to the customer will enable Amazon to fill a variety of orders inexpensively and quickly. Delivering what the customer wants, when she wants it, at a price she is willing to pay is the ultimate value proposition.

But there are three things that Amazon needs in order to deliver the three s’s. First and foremost, it needs data, both external and internal. External data include information from Amazon’s own customer base and the customer bases that come in via acquired companies. It can mean data from the marketplace, which includes competitors and companies with other business models and innovations. Amazon also needs internal data. How are the internal processes doing? Where can they be improved? Are there bottlenecks that can be eliminated?

Amazon also needs innovation to retain and enhance its customer-centricity. This could be innovation in product (such as Alexa, the voice service that powers the Amazon Echo), process (such as delivery by drone), or content (such as the Amazon original TV series Fortitude). With Amazon facing ever-changing customer needs, the ability to marry data with innovation will be a key driver of the company’s future success.

Lastly, as the company increasingly moves from the online world to the offline, it needs to think of ways of replicating its platform strategy offline. The ability to offer a wide range of products online was made possible by bringing third-party sellers onto Amazon’s platform. These sellers provide mainstream products, plus they extend the breadth of product offerings by giving consumers access to more obscure products (those in the “long tail” of customer needs). This reinforces the consumer benefit from visiting and shopping on the Amazon site. Initial moves at Whole Foods seem to be going against this notion, however, as the acquired company announced a reduced emphasis on local suppliers. But Amazon needs to nevertheless explore ways in which it can better leverage physical locations as local platforms.

The idea behind the three s’s, and what is needed to support it, bears a strong resemblance to what Amazon refers to internally as the “flywheel.” In the traditional strategy literature, organizational “fault lines,” where one activity may require skills that are not consistent with those required for other activities, are associated with the organization’s need to manage the three s’s. What Amazon has been able to do thus far, and needs to continue to do, is manage effectively across these fault lines.

Putting the three s’s into action Now let’s get back to the original question of why Amazon acquired Whole Foods and, in light of the above analysis, examine various reasons Amazon provided.

·One argument is that as grocery purchasing increasingly migrates online, Amazon will be able to use its access to Whole Foods to fulfill this need.

·Another is that Whole Foods can act as a distribution hub since it has urban and suburban locations. Because the locations have attractive demographic profiles, with high-earning residents, Amazon can physically reach its customer base in these areas. In addition, the stores can become showrooms for Amazon products, such as Alexa, that have been optimized to allow consumers to shop more easily on the Amazon website.

·Third, and related, is that as Amazon gets access to the Whole Foods customer base, Whole Foods shoppers who are not big Amazon buyers may be tempted to sign on with a Prime bundle designed specifically to appeal to them.

·Fourth, the company will get more out of customer data. By combining offline data from Whole Foods with online shopping data, Amazon may be able to further refine the scope of its product offerings.

·Fifth, with its experience in running its own operations efficiently, Amazon may help improve the efficiency of Whole Foods operations. From sourcing and dynamic replenishment to dynamic pricing and streamlined store operations, there are many ways in which the companies may be able to lower costs while enhancing the overall customer experience.

Other reasons: the retail locations can become sites where customers who find store returns convenient can return products purchased on Amazon, rather than go to the post office or UPS store. Also, the acquisition gives Amazon access to a set of retail employees considered some of the most customer-centric in the business, and who may help Amazon better understand ways of enhancing employee satisfaction at Amazon itself. Ultimately, as many marketers have pointed out, the profit chain runs through both employees and customers.

The acquisition also gives Amazon access to Whole Foods’ private-label product line 365. Recall the customer’s journey for detergent. The one factor that Amazon still has no control over is the detergent itself, since detergents are manufactured by outside companies. Because this limits Amazon’s profit margins, the company has increasingly been launching its own products—AmazonBasics batteries and cords, for example. This own-brand push will be significantly enhanced by the 365 line from Whole Foods.

Many more reasons for the acquisition have been advanced, but as should now be clear, most of them fit into the broad rubric of enhancing Amazon’s scope, scale, and speed. Indeed, the acquisition also has a direct impact on some of the enablers: data, innovation, and platform.

While growing size, product, and service variety are clear advantages for now, Amazon cannot discount the possibility of upsetting customers as it engages more deeply in their lives. I was recently on the site, trying to buy some cranberries. I was met with a dizzying array of products and processes including AmazonFresh, Amazon Prime Pantry, Amazon Prime, and a host of third-party sellers. These options, plus even more unique possible combinations, made me decide to buy the product elsewhere. In the end, I was unable to locate the right combination of product (organic cranberries in a 3 lb package), process (Prime), and price—even though I knew that the right combination existed somewhere in the multitude of search results.

I find there’s typically a movie quote for every situation—and in this case, a perfect one comes to mind. Toward the end of The Lincoln Lawyer, the title character, Mick Haller (played with gusto by Matthew McConaughey), offers his services for free to a potential client. His chauffeur, Earl (played by Laurence Mason), overhears this generous offer and asks, “Are you all right?” To this Haller replies, “Repeat customers, Earl. We’ll stick it to ’em next time.” As Amazon scoops up customers who become more reliant on it, these customers should hope that the company does not behave like Haller and stick it to them down the line.

Pradeep K. Chintagunta is Joseph T. and Bernice S. Lewis Distinguished Service Professor of Marketing at Chicago Booth. He blogs at kiltscenter.tumblr.com. He thanks Booth MBA student Yogesh Kansal for his feedback and input.

0 notes

Photo

If Sears Wants to Sell Kenmore...

When a retail chain such as Sears is in trouble, the usual levers to examine in order to improve performance are location (or convenience); assortment (or the variety of categories carried and the brands within each category); price (price positioning – upscale, midscale, etc. and pricing or merchandising strategy – everyday low pricing or “high-low” pricing); and most importantly, the overall quality of its merchandise.

Over the years, the company has tried to move the needle by engaging each of these levers. For example, it’s experiment of opening a store in downtown Chicago in 2001 to serve the clientele coming to that area to shop at neighboring stores (including Macy’s, Old Navy, Gap, Target etc.) ended in 2014 as it failed to generate enough traffic and sales to justify the premium location. In 2002 it tried to return to its catalog roots (Sears that started as a mail order catalog company in the late 19th century and started opening retail locations only in 1925, abandoned the general merchandise catalog in 1993) by acquiring the Land’s End – a higher end clothing, luggage and home furnishings catalog retailer. However, that did not end well either with Sears spinning off Land’s End in 2013. And further back in 1989, Sears tried to move from a high-low pricing policy, where merchandise is sold at a higher regular price coupled with occasional discounts of varying depths on different products, to an everyday-low-price strategy (akin to Wal-Mart’s) where regular prices are lower but there are fewer discounts. This attempt also resulted in failure, as the customer who came to Sears wanted to feel the thrill of having discovered a quality product at a low price. So over the years, Sears has been declining. It first started losing out to Wal-Mart and Target in the bricks-and-mortar era; unable to compete with Wal-Mart at the lower-end value positioning or at the slightly upper end with Target. More recently the online assault mounted by Amazon has largely decimated what was left of the “Great American Store.”

Unlike many other retail chains however, Sears owns several brands that are well known and trusted by American consumers. These include the Kenmore range of appliances, Craftsman tools and Die Hard batteries (jointly known as K-C-D). Recently, the company has sought to raise money by selling these iconic brands. First among them was the sale of the Craftsman brand to Stanley Black & Decker, another larger manufacturer of tools. While the Craftsman range will still be available in Sears stores, ownership will pass to the purchasing company. Sears has also been interested in selling the Kenmore brand. Clearly there are other manufacturers such as Whirlpool, Electrolux (a Swedish manufacturer), Haier (a Chinese appliance maker), Samsung and LG (Korean manufacturers) who could potentially be interested in acquiring the Kenmore brand name. Obviously there are financial, operational and other considerations that would go into the decision to acquire the brand. Here, I take a limited perspective by (i) focusing on the consumer to see if the Kenmore brand provides a better “fit” to these other players; (ii) ignoring the two big Korean manufacturers from the analysis (since these are large conglomerates with interests well beyond appliances the calculus for these firms will likely be very different); and (iii) looking at what consumers say on one specific social media platform - Twitter. The caveats from doing so are obvious; nevertheless such an analysis might provide some insights for these firms.

Yogesh Kansal (MBA 2018) as always helped me with this analysis; and for this particular post I also received assistance from Shweta Desiraju (College 2017). I look at data from the 2-month period from November 7, 2016 to January 7, 2017 for the analysis.

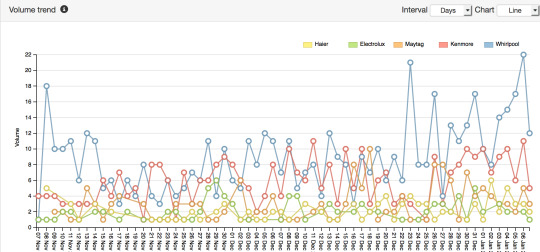

As always I begin by looking at “buzz” – the amount of activity being generated on the platform by the various brands. The reasoning here is that if Kenmore is a brand generating buzz and you are a brand that is currently not front and center in the consumers’ minds then acquiring a brand with more “top of mind” awareness might be beneficial for you. Figure 1(a) shows the temporal variation in the relative number of posts on Twitter for each of the brands and Figure 1(b) shows the overall numbers for the entire duration.

Figure 1(a): Time series plot showing relative numbers of tweets

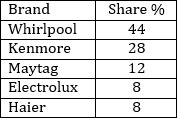

Figure 1(b): Overall share of posts of the brands

We see from Figure 1(b) that Whirlpool and its subsidiary Maytag, already control over 50% of all the conversations in this market. So per se, adding Kenmore to the mix, while significantly expanding coverage, is less of a benefit (of course, since Whirlpool already does the manufacturing of some Kenmore products an argument can be made from an operations perspective). However, both Electrolux and Haier will benefit significantly from adding Kenmore to their portfolios while giving them access to the US market.

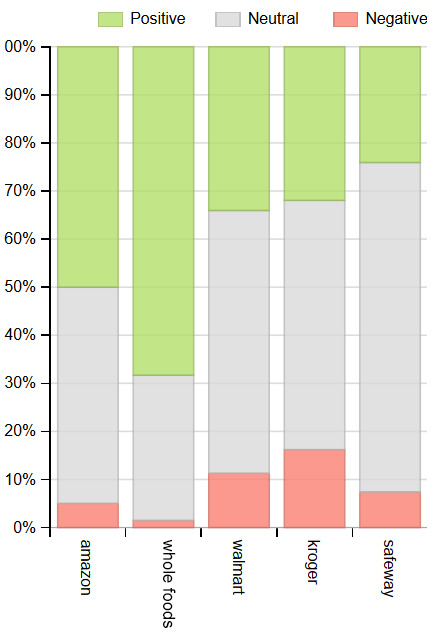

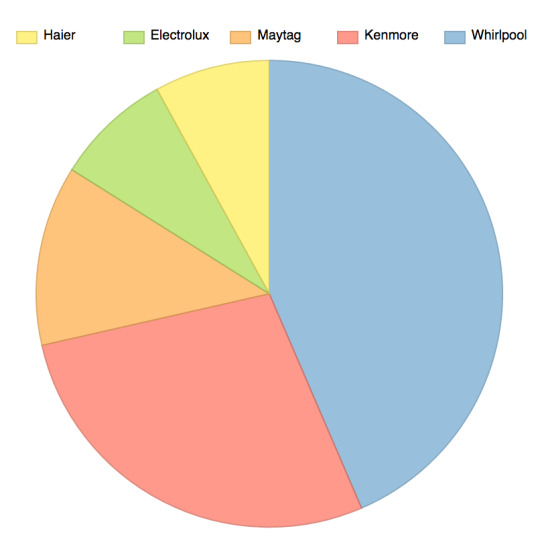

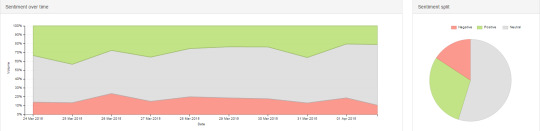

Does the volume of conversations also carry over into benefits from the sentiments associated with these brands? In Figure 2, I show the positive (green), negative (red) and neutral (grey) sentiments associated with each of the 5 brands analyzed.

Figure 2: Brand sentiments from the tweets

From Figure 2 we see that the brand likely to benefit the most is Haier since the sentiments associated with its tweets are less positive than those for the other brands (with the possible exception of Whirlpool). Kenmore has the highest positive sentiment associated with it, making it a valuable addition to the company’s product portfolio. Also note that Electrolux in this case is already generating fairly high positive sentiments although the negative sentiments are also high for this brand. From that perspective Electrolux might also benefit from an association with Kenmore.

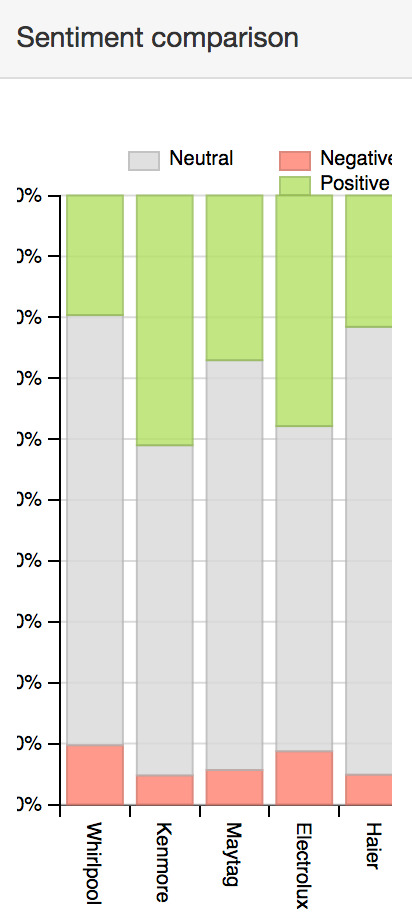

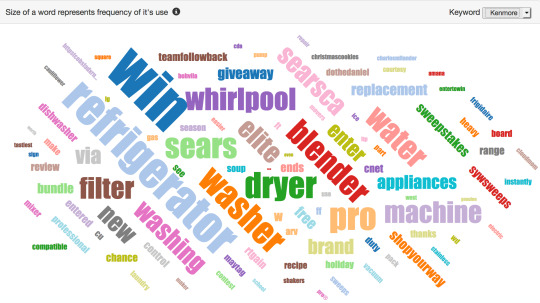

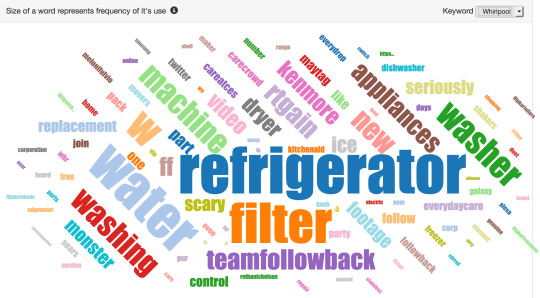

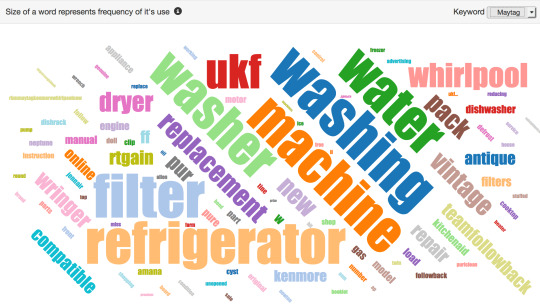

Next we look at the contents of the tweets from the different brands via wordclouds. The idea behind this is whether there are some complementary features or other attributes that Kenmore provides from the perspective of each of the other brands. Figures 3(a) through 3(e) display this information for the 5 brands.

3(a): Haier Wordcloud

3(b): Kenmore Wordcloud

3(c): Whirlpool Wordcloud

3(d): Maytag Wordcloud

3(e): Electrolux Wordcloud

From the wordclouds it appears that the brands are all very similar in terms of the content of the tweets. Other than Maytag, the refrigerator appears to be the major appliance that generates most of the tweets. The one dimension that Kenmore could potentially bring to each of the other brands comes from its product line also including small kitchen appliances such as blenders. This is reflected in its wordcloud as well.

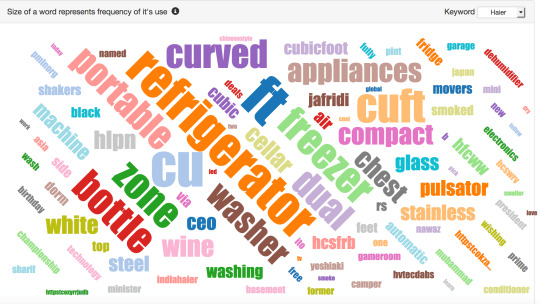

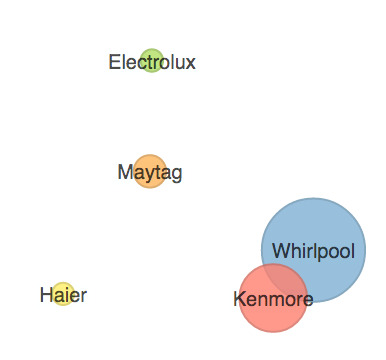

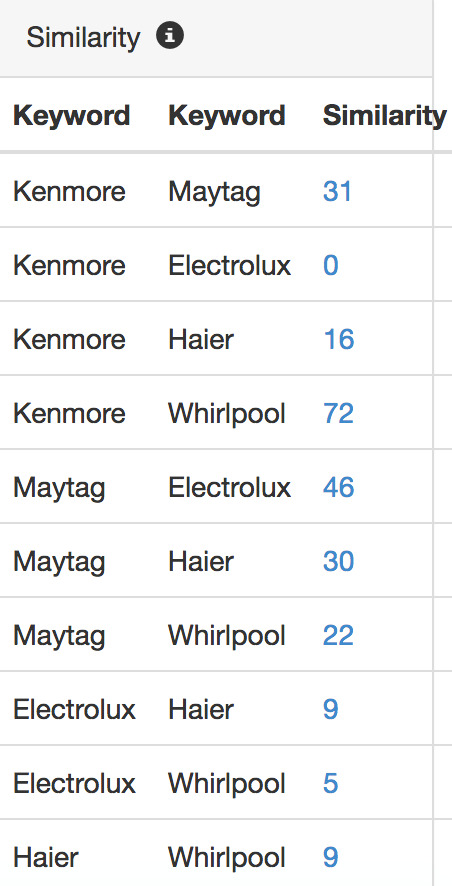

To dig deeper into the perceived “similarity” between the various appliance makers in terms of the overlap in words used in their respective tweets, I next construct a similarity “matrix” that provides the extent of word overlap between brands. This overlap metric is akin to a correlation matrix. With this similarity matrix as an input one can use standard statistical methods to come up with a “perceptual map” such as the one in Figure 4 below. The size of each bubble is proportional to the number of tweets for the corresponding brand.

Figure 4: Perceptual Map and Similarity measures

Note that unlike a typical perceptual map, the dimensions in the above figure are not specified and are open to the reader’s interpretation. Nevertheless, the map provides a pictorial representation of the similarities in the tweets between the 5 brands. In particular, those of Whirlpool and Kenmore appear to be quite similar to one another, reinforcing the earlier point that the benefits to Whirlpool of combining with Kenmore maybe limited. On the other hand, it does appear that both Haier as well as Electrolux would benefit given the limited similarity / overlap that they share with Kenmore.

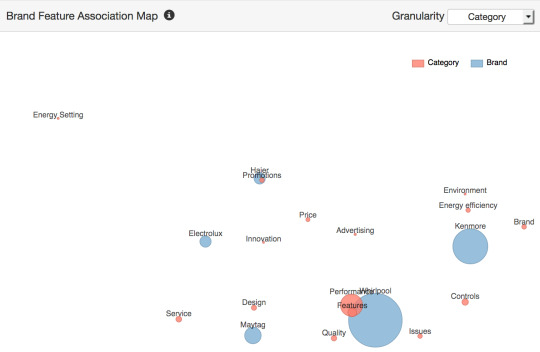

Since the above map does not give much information on the underlying attributes, I turn next to mapping the brands onto features via the following feature association map. This map provides information on which “topics” are included in the content of the tweets and the topics related to each of the brands. I interpret these topics in terms of the features of interest to consumers. The Feature-Association map is depicted in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Feature – Association Map

Figure 5 shows interesting differences across brands in terms of the features most closely associated with them. In particular, Whirlpool tweets reflect product features, performance and quality but also issues that consumers maybe having with them (recall the large negative and low positive sentiment associated with this brand). Maytag’s tweets reflect design, quality and service and Kenmore’s are associated with the brand, energy efficiency and the environment. On the other hand Haier seems most strongly associated with price and promotions (and design to a lesser extent) and Electrolux with innovation, design and service. Based on this information, it does appear the Haier may be the firm that would benefit the most from being associated with a strong brand that also emphasizes energy efficiency.

Taken together, the above analysis seems to suggest that Kenmore would make a good purchase for Haier or Electrolux but perhaps for different reasons. For Electrolux, Kenmore would bring more visibility in the US market and a strong brand with an association with the environment and energy efficiency. For Haier the benefits include the visibility as well as the positive sentiment as well as a move beyond just being associated with price and promotions. It will be interesting to see how this plays out going forward.

.

0 notes

Text

Calls & Recalls: Samsung Note 7 – What the data tells us

In the previous two posts I discussed the reason why the recall of the Note 7 was important and what the potential reasons behind the recall may have been. Here, with the help of Yogesh Kansal (MBA ’18), I will look at Twitter data from August 15 to September 15 to see if there are any insights we can obtain from those data. Keep in mind that the data come from the publicly available 2 percent of tweets that Twitter allows us to freely access. Before getting started, let’s review the timeline of events.

Timeline of events (Source: Wikipedia):

August 2, 2016: Samsung unveils Galaxy Note 7

August 19, 2016: Samsung’s official release date for Galaxy Note 7

August 31, 2016: First report that Samsung is delaying release to "perform additional tests"

September 2, 2016: Samsung voluntarily recalls Galaxy Note 7

September 7: Apple unveils iPhone 7

September 8: FAA issues advisory warning for Galaxy Note 7

September 9: Consumer Product Safety Commission issues warning to stop using the Galaxy Note 7

September 16, 2016: Apple releases iPhone 7

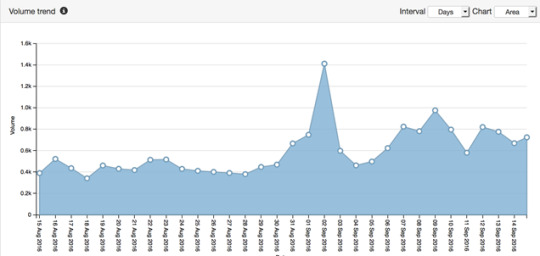

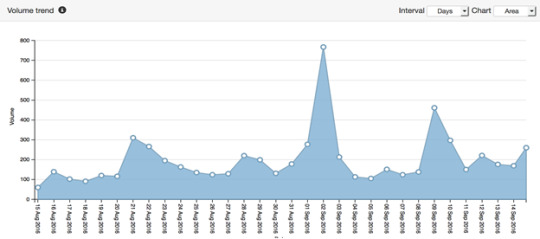

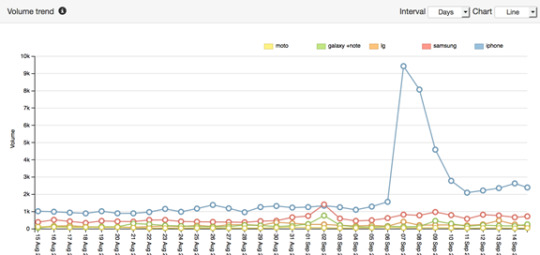

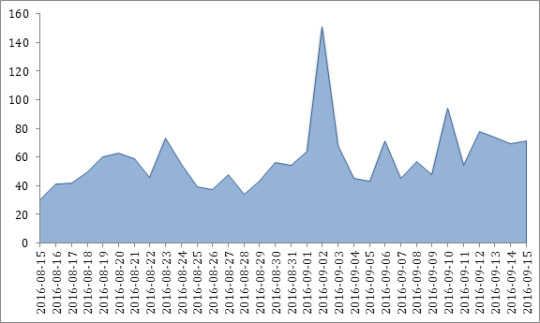

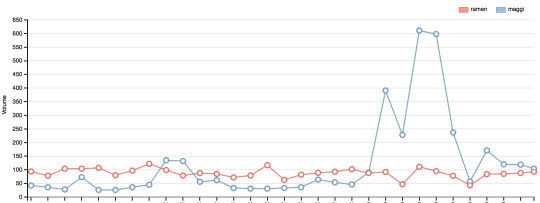

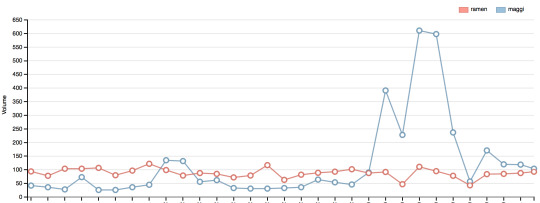

I begin in Figures 1 and 2 by plotting the time-series in tweet volume over this time period for “Samsung” and for “Galaxy Note.” Not surprisingly, we see a spike corresponding to the recall announcement on September 2. There is also a spike corresponding to the times of the CPSC and FAA warnings. In addition, we note from both figures that the numbers remain somewhat elevated all the way through the middle of the month.

Figure 1: Volume trend for Samsung

Figure 2: Volume trend for Galaxy Note

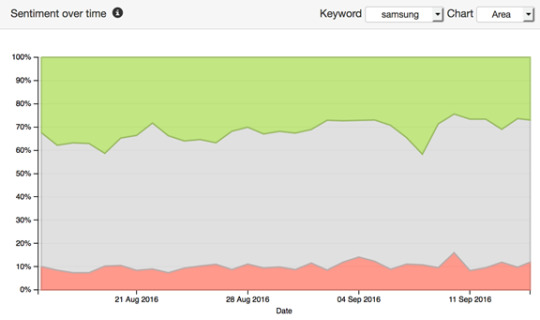

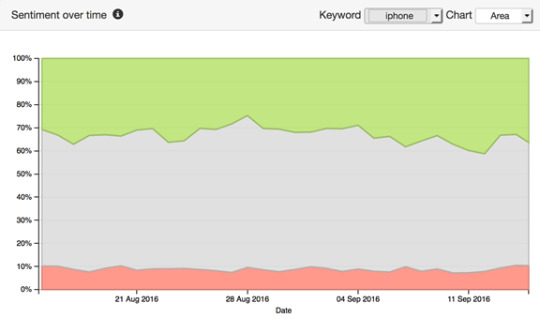

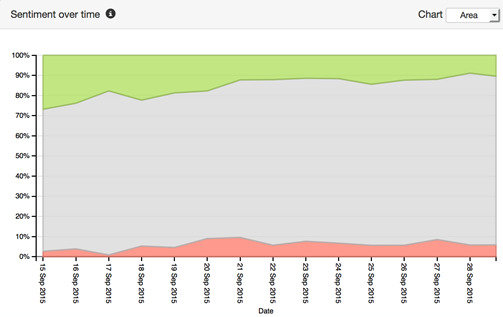

Next, we look at the overall sentiment for the “Samsung” brand in this period. The split, which was 31 percent positive, 59 percent neutral and 10 percent negative, indicates that overall, Samsung has not been too badly affected by the recall (we’ll compare this with number for other brands later). This is also evident from the sentiment trend that I plot in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Sentiment trend for Samsung

What about the Galaxy Note sub-brand? The news is less positive. Here the overall positive sentiment is only 21 percent and shows a clear dropoff over time (see Figure 4). However, the negative sentiment is not too high but shows peaks around August 31, when the announcement of shipment delays was made, and then again after the FAA and CPSC warnings.

Figure 4: Sentiment trend for Galaxy Note

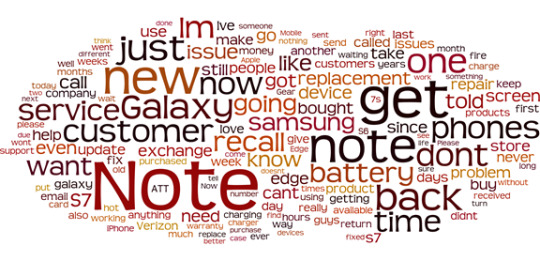

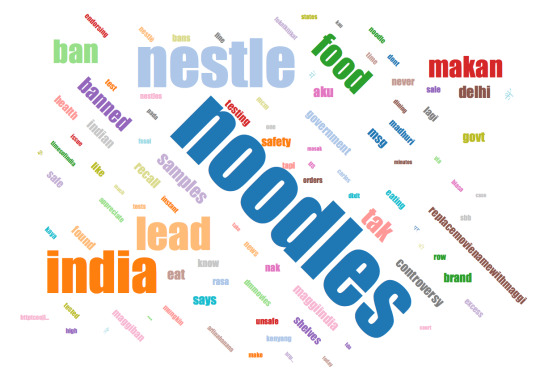

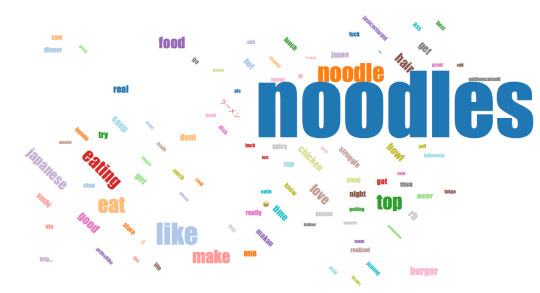

Digging more into the two negative sentiment peaks mentioned about, we see the following in the word clouds formed from the tweets on those days. Consumers are clearly unhappy about the delay in the shipments, as shown in Figure 5. This is understandable since this would eliminate bragging rights the Samsung owners would have vis-à-vis buyers of the Apple iPhone 7, which was set to come out later.

Figure 5: August 31 negative sentiment word cloud

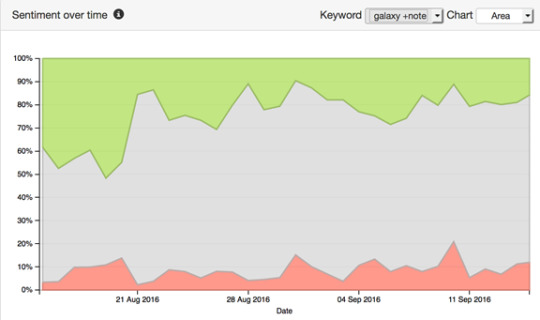

Figure 6 shows that consumers were confused by the recall. Samsung could have reacted to their confusion by issuing clear instructions. In the context of a global launch, where different governments may require different interventions, Samsung needed to come up with a comprehensive global response.

Figure 6: September 9th negative sentiment Word cloud

Putting things in context:

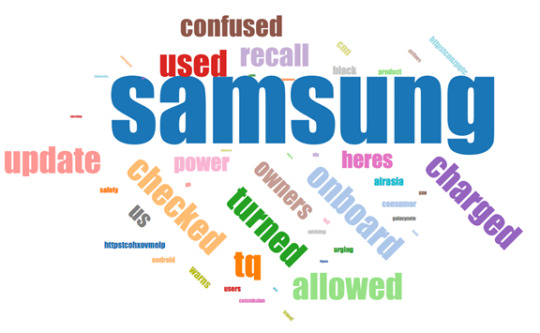

Next, I put the action on Twitter related to Samsung and the Galaxy Note in context with the conversation around Apple, LG, and Moto at the same time. Figure 7 shows that despite the peaks we saw earlier in Figure 1, the volume of tweets in that figure is dwarfed by the tweet volume generated by the iPhone. Indeed, the volume for the iPhone is several orders of magnitude larger than that of the other players in the market. This is especially obvious around the time of the iPhone announcement on September 7. While one may believe there was considerable buzz around the Samsung event, it was quite small in the context of the iPhone. In this time period, 65 percent of tweets were about iPhones, 20 percent were about Samsung, 7 percent were about the Galaxy Note 7, 7 percent were about LG, and 2 percent were about Moto.

Figure 7: Twitter volume trend across brands

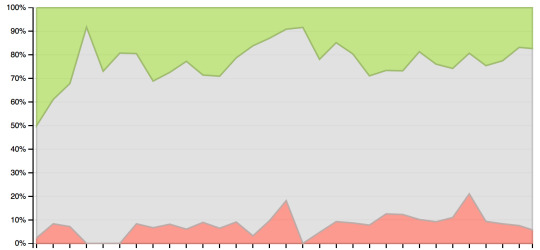

Next, what about the sentiment across the brands? We look at the overall sentiments across these brands in the one-month period. This information is depicted in Figure 8. It is clear that Samsung and Galaxy Note have the lowest positive sentiments, although negative sentiments are no higher than those for the other brands. So working to regain the trust of the customers would hopefully result in an increase in positive sentiment.

Figure 8: Sentiment comparison across brands

Do other brands benefit from Samsung’s travails? In Figure 9, I plot the sentiment trend for the iPhone. While there does appear to be a slight uptick in positive sentiment, this could easily be attributed to Apple’s own announcement of the next-generation iPhone. It appears there aren’t any major beneficiaries of Samsung’s missteps.

Figure 9: Sentiment trend for iPhone

Some information from Facebook

The last chunk of data we’ll look at are Facebook posts on the Samsung Mobile USA page in the two-week period prior to September 2 and the two-week period after. The contents are depicted as word clouds in Figures 10 and 11. There aren’t a whole lot of additional insights to get from these figures. Essentially, Figure 11 reflects issues raised vis-à-vis the recall and the battery problem as would be expected.

Figure 10: Wordcloud for the two-week period up to September 1, 2016

Figure 11: Wordcloud for the two-week period from September 2, 2016

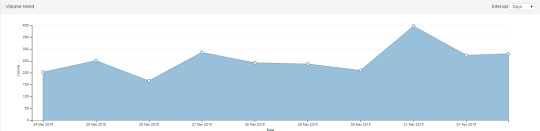

What about the volume of Facebook posts? Are they similar in pattern to that observed for tweets or is there a difference? In Figure 12, I plot the post volume. It is clear that the pattern is very similar to that for tweets with peaks on roughly the same days and of similar relative magnitudes.

Figure 12: Volume trend for Samsung Mobile USA Facebook posts

What about the sentiment of these posts? This is depicted in Figure 13.

Figure 13: Sentiment trend for Samsung Mobile USA Facebook posts

As with the volume of posts, we see that the sentiment of the posts also closely mirrors what we saw with the tweets with obvious spikes in negative sentiment at the anticipated dates. Nevertheless the overall sentiment does not change dramatically to the negative.

Overall, the above look at the data suggests that while problematic, and while holding important lessons for Samsung going forward, they should be able to eventually overcome the fallout from the Galaxy Note 7 recall. Most of the negative sentiment seems focused on the specific product rather than the parent company. Perhaps this is an instance where having a product line might have contributed to the problem while at the same time limiting the extremely negative consequences of the incident. Of course all this depends critically on whether the company moves decisively to address the problems. The announcement that replacements begin shipping (at least in South Korea) on September 28 is hopefully the first step in the process.

0 notes

Text

Calls and recalls - Causes and consequences of the Galaxy Note 7 disaster

“There’s a saying in England: where there’s smoke, there’s fire.” So said James Bond, played by the inimitable Sean Connery, after setting fire to a bunch of Spectre boats in the movie from From Russia with Love. The recent outbreak of flammable Samsung Galaxy Note 7 phones suggests the reverse—where there are fires, there must have been some smoke. There must have been some signals ahead of that unfortunate outcome for Samsung. So what may have been some of these signals and the reasons behind them?

First is the issue of product design. The smartphone market has become more competitive, and in recent times we haven’t seen the types of technological breakthroughs that characterized the early period of the product’s life cycle. Manufacturers have instead focused on making phones bigger, thinner, faster, and brighter. This and the desire for a longer battery life put a lot of pressure on the design of the Lithium-Ion battery embedded in these phones.

According to cNet, this is why there’s little room for error:

“Phones use lithium ion battery packs for their power, and it just so happens that the liquid swimming around inside most lithium ion batteries is highly flammable. If the battery short-circuits – say, by puncturing the incredibly thin sheet of plastic separating the positive and negative sides of the battery – the puncture point becomes the path of least resistance for electricity to flow. It heats up the (flammable!) liquid electrolyte at that spot. And if the liquid heats up quickly enough, the battery can explode.”

Firms in general (and in this case, Samsung in particular) need to very sensitive to the products��� design parameters.

The second issue is product testing. The best way to minimize the probability of such problems is to subject the product to rigorous testing: alpha tests, performed in-house; beta tests, with some subset of customers; and delta tests, which assess longer-term wear and tear. With the pressure on to bring to market new and improved devices, the amount of testing that products are being subjected to is likely declining. Less testing, in conjunction with more complexity of design, is likely to increase the likelihood of episodes such as those recently suffered by Samsung.

The third aspect, perhaps more unique to Samsung, is that unlike Apple, which generally sells only one (or more recently, two) flagship product, the company sells an entire product line with several series, including A, C, E, J, S, Y, and Note. It has more products to test. An issue with even one of the products is liable to damage the company’s reputation. Designing and testing each product in each of the lines is clearly a challenge for the company, even before it faces the marketing challenge of differentiating these series in the minds of consumers (of course, some of the series are country specific, e.g., the C series was launched in China).

The above factors may have all contributed to the greater likelihood of the Note catching fire. Along the same lines, there are marketplace factors that Samsung (and other manufacturers for that matter) needs to pay attention to in the future. The first issue that should make companies more circumspect when launching products is the new pricing and promotion policies being followed by wireless service providers. As the technologies underlying the products advance (faster chips, brighter displays), the cost of manufacturing remains high ($255 by one estimate) and the market prices for the phones keep rising. Granted, Samsung is in a somewhat enviable position of being more vertically integrated than other manufacturers, and so according to the above source has managed to keep costs in line with that of the previous generation phones. But a high retail price has implications for consumers. In the past, wireless carriers like AT&T and Verizon would subsidize the cost of the phone to the consumer. In effect, the consumer paid only about $199 for the device. However, facing competitive and margin pressures of their own, these wireless carriers have started to end the price subsidies and now consumers are required to pay full price (albeit, in most cases, in installments). If consumers are paying $700 for a phone, when they used to pay $200, they’re likely to be a lot more sensitive to a phone’s quality. Having the device catch fire could have longer-term consequences in this new pricing and promotion regime. In other words, it would behoove Samsung and its rival manufacturers to take into account that consumers are spending more than ever before when making a smartphone purchase and expect to have a robust device for that price.

A second marketplace consideration for Samsung is the role of the wireless carrier. In most cases these service providers are also the device’s distributors. When a device is recalled, carriers need to work with the customers who previously purchased the phone to retrieve the recalled phones and provide a replacement. There is also the issue of phones in the carriers’ inventories. In a world with a few device manufacturers, wireless carriers may be more dependent on these manufacturers. However, there are several manufacturers now competing for share in the devices marketplace making the carriers less dependent on a particular manufacturer, especially one that might be having an issue with its products. Samsung needs to recognize the power of the carrier and ensure that it keeps its relationship with these players strong.

In the movie Suicide Squad, the character Harley Quinn (played by Margot Robbie) retorts to a disapproving statement by Rick Flagg (Joel Kinnaman) thus: “We’re bad guys, it’s what we do.” Fortunately, that statement does not apply to Samsung. Exercising care in future new product launches will save it from such a reputation in the future. This would help it avoid long-term negative fallout from the incident. Hear Pradeep Chintagunta speak more about the recall incident on a recent episode of Marketplace.

Special thanks to Yogesh Kansal (MBA ’18) for his help with this post.

#booth #marketing #recall #product design #product testing

0 notes

Photo

Calls and recalls - The Samsung Note 7 smartphone

Like Scarecrow in the Wizard of Oz, who screams “Help! I’m burning! I’m burning!,” the owners of the Samsung Galaxy Note 7 phones that recently caught fire must have felt seriously singed. It was not the first time that Samsung has had troubles with the batteries in its cellphones. Both the S3 and S4 generations had issues with batteries that couldn’t hold a charge, and swelled up (prompting the infamous battery “spin test”). As consumers we have also experienced explosions with laptop batteries (Sony’s recall of Panasonic batteries in June and its recall of laptop batteries in 2006) and car batteries (Chevy’s earlier problems with the Volt’s batteries). In each case, Lithium-Ion batteries have been the culprit. The public is aware of issues with these batteries, but since batteries are usually hidden within our laptops, smartphones, and cars, we tend to not think about the potential dangers they present. With this as background, why all the brouhaha about the Galaxy Note 7? There are several reasons.

The first is that the Galaxy Note 7 was very popular prior to recall. It had received good reviews, and Samsung had manufactured and distributed several million. When the company recalled 2.5 million phones, several people, including children, had reported injuries and other incidents (like cars catching on fire). At the same time, the Galaxy Note 7’s manufacturing defect affects less than 0.01 percent of all Note 7 handsets sold, according to unnamed sources from within the company. It’s possible that we’re looking at fewer than 1,000 defective phones. However, this is of little solace to the consumer who has no way of knowing whether (s)he has one of the defective ones. By contrast, many in my generation can recall Intel’s “Pentium flaw,” when Intel’s flagship microprocessor chip would mess up certain simple arithmetic operations. While Intel claimed that the common user would experience the flaw once every 27,000 years, examples of the flawed computation were widely available that prompted consumers to immediately determine whether or not their machines had the flawed chip! The bottom line is, consumer products like smartphones are supposed to improve our lives—not make them more difficult. The concerns about the Galaxy Note 7 are completely justified from this perspective. Scale and ubiquity simply exacerbates the problem.

A second reason is that Samsung considered the Galaxy Note 7 to be an important driver of revenue for the company. In its Q2 2016 earnings release, the company notes the following under Q2 results and business outlook:

Focus on YoY earnings increase by strengthening H(igh)/E(nd) line-up and maintaining solid profitability of mid to low-end products

- High-end: Maintain solid sales led by new flagship product launch and continuous global sales of S7

- Mid/Low: Expand global sales of A/J series while streamlining product line-ups

Not only are smartphones an important part of Samsung’s business, but in addition to generating revenues on its own, the flagship Galaxy Note 7 does a lot to pull in sales for other products lower down in the product line. So the Galaxy Note 7 (and the S7) is a key part of the company’s strategy.

A third reason is the presence of competitive considerations. First, Samsung has been under a lot of competitive pressure in non-US markets from a number of domestic players—Huawei, Oppo and Vivo in China; Micromax in India, etc. While many of these players used to compete in the mid-to-low end of the smartphone market, they are all moving upmarket to challenge Samsung. Second, Samsung competes heavily with Apple in the US market. By being able to launch its latest-generation phones before the iPhone 7, it looked like Samsung had managed to steal the thunder from Apple’s launch. Indeed this notion got further credence from the positive buzz surrounding the Samsung product. So the timing of the Samsung recall just prior to Apple’s launch announcement for the iPhone 7 last week really seemed to take the wind out of Samsung’s sails. The iPhone has since reported very strong early orders and while it may be highly premature for Apple to declare victory for this generation of smartphones, the fact that Samsung has halted sales of its own flagship product does not hurt.

Finally, the way Samsung has gone about the recall has been criticized by many. For example, the Wall Street Journal ran this headline:

“How Samsung Botched Its Galaxy Note 7 Recall.”

As I have repeated often in this column (see many of my earlier posts including those on the VW scandal and the Maggi lead crisis), the response to these incidents has to be swift, sincere, and solutions-oriented. So far, Samsung has been found wanting at least along some of these dimensions. Eventually, being a strong consumer company, Samsung should be able to bounce back. After all, even the fire from Scarecrow eventually ended up destroying the Wicked Witch of the West, so some good might come out of the battery incident. In the short-run however, it seems that it is Samsung that has been burned.

Special thanks to Yogesh Kansal (now MBA ’18!) for his help with this post.

#samsung #BoothMKTG #chintagunta

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Creating a brand in a fragmented marketplace: The Indian Experience

There are several industries in emerging markets that tend to be highly fragmented – retail, artisanal crafts, indigenous clothing. These industries are characterized by firms with limited brand recognition on a national level (although many of them have a strong presence in small local areas). An increasingly widespread phenomenon in these markets is the emergence of national (or super-regional) branded players who have tried to transform these industries into brand-conscious ones. Before jumping into the factors that might be driving this phenomenon, let us first revisit the role of branding in a broader marketing context.

As I have noted in an earlier post, the basic objective of marketing is to generate demand – this is where companies focus on fine tuning their marketing strategy and marketing mix to better cater to consumer needs so they end up buying more; perhaps even creating longer-term relationships. The second objective is to build brands – essentially the marketer wants to create an associative network of benefits, emotions, images, etc. that are unique to her product or service. This helps sustain the relationships the marketer is trying to engender. The third objective is to create completely new categories of products where none existed before – this way the brand becomes synonymous with a category – say like Xerox. And finally the role of marketing is to aid society by not only accomplishing the first 3 objectives but also benefitting the larger society at the same time – think of products like the Pure-It water filter. So branding fits into this larger rubric of marketing.

So what are the factors that are leading to a push towards brands in fragmented markets? There could be several factors – here are some.

i) Differentiation. First and foremost, branding is a means of differentiating your product from the other “unbranded” products out there. Consider the case of atta (the flour that goes into the making of the Indian bread or roti). The consumer had typically used atta that was ground in their presence or in the neighborhood mill. Such a fragmented market is often ripe for entry by a branded player. Why? First, any individual player in this market has very limited market power. Consumers typically purchase raw wheat in bulk, clean it by hand, store it, and bring some every week to the local mill or chakki, where it is then ground to produce the atta. But as smaller mills get replaced by larger mills, a consumer’s access to mills decreases as there are now fewer mills available. In urban areas, the cost of real estate also affects the ability of a small mill to continue operations. Further, consumers have less time to devote to this activity themselves or to get it done in a mill. Second, the market for the product is large. So even if the branded player can only get a small share of the market, it can create a profitable business opportunity. Fragmentation associated with a large market size was also a driver in the jewelry business and now in the saree business as well. With product categories like food and jewelry, branded players can also create a strong emotional bond between consumers and their products via advertising – something the players in the fragmented market may not be able to afford other than in a very localized manner. Related to this point is that if the product is largely perceived as a commodity (as in the case of atta), any means of differentiation is likely to stand out. A downside however in such markets, with several branded players, is that the market can become price competitive as was the case when ITC entered the atta market.

ii) Quality assurance. A second reason for creating brand affinity is that of quality assurance. In a fragmented market that is based on a strong relationship between the firm and the customer (as in the traditional jewelry business), the relationship servers as the basis for quality assurance. However, for the inexperienced consumer or one that only needs the product occasionally, quality assurance based on relationship does not exist. At the same time, given the big ticket size and the possibility that the jeweler may be adulterating the product, the risk associated with the purchase is high. In such instances, a strong brand can effectively signal high quality to the consumer. Consider for example, a household in S India that traditionally consumed rice, wants to switch to wheat and rotis due to diabetes concerns. Since this household is not experienced with the category, they might be more likely to be drawn to a branded atta that advertises on television compared to a no name atta purchased in the neighborhood store. Another category where brands play the quality assurance role is pharmaceuticals. Knowing that the drug is a “branded generic” produced by a reputable companies provides assurance to the physician that her patient will get access to the molecule that she is prescribed. Viewers of Tanishq commercials starring the film stars Jaya Bachchan and her husband Amitabh might recall the emphasis on quality assurance communicated in these ads: “Do you know anything about diamonds, whether they are pure or not?” she asks him. To which he is able to respond that the diamonds are all of the same quality, and that the diamonds can be exchanged if she did not like them.

iii) Status symbol. Brands can signal status – in some cases like automobiles, the signals can be overt. Driving a Mercedes-Benz for example, conveys to the bystander something about the passengers riding in that car. Similarly a jewel collection from Tanishq can communicate its exclusive and expensive nature to the right social circle that the wearer moves in. We can also start to see this in sarees – the ability to manufacture designs and prints exclusive to a particular brand or label – has the potential to signal status to the appropriate audiences. This is clearly related to the issue of differentiation. Being seen as a status symbol allows the brand to differentiate itself from other brands that cater to the mass market. This in turn allows the firm to charge a premium price for its offerings.

iv) Primary demand generator. When markets are fragmented, there is less of an ability for firms to stimulate primary demand. Consider the case of Indian consumers interested in desi clothes, i.e., Indian ethnic wear. For the small ethnic retailers in a given urban area, it would be difficult to get consumers to switch or augment their wardrobes with ethnic fare. First, they lacked resources to convey the value proposition effectively to these potential customers. Second, it would have been hard for the customer to have come across these retailers due to their small footprint. Enter a brand like Fabindia that decided to shift its business model from an export focus to one of India-based retail. Now you have a national brand with considerable retail footprint and access that could enter a consumer’s consideration set while buying clothing. This generates primary demand for such clothing that would have been difficult to do without the brand.

Besides brands like Tanishq for jewelry, and Fabindia for ethnic wear, one can also think of players like Amul, Mother Dairy and Aavin that have transformed the dairy products space from one with considerable fragmentation to a more streamlined supply route from the farmer to the consumer.

Going the branding route is not without its challenges. The first is to communicate effectively to the consumer that there is value in the branded alternative above and beyond the value that can be obtained in the unorganized sector. In other words, there needs to be a believable and communicable point of differentiation. In the case of Pillsbury’s Chakki Fresh Atta that was launched in 1998 it was the following aspiration of the Indian housewife “I wish there was a way to keep the rotis in my husband's lunch box soft till the time he eats them;” rotis so soft they stay soft over six hours (from the time of preparation around 7 AM to the time of consumption around 1 PM). But even if the value proposition is well communicated, if the consumer is very focused on price, it may not be possible to penetrate the market much. So the branded atta market is perhaps still about 2-3% of the overall (albeit large) atta market. The second challenge has to do with creating, maintaining and potentially expanding the product’s supply (or demand) chain. Consider the case where the branded firm does a good job of generating demand for the product. Growth in demand usually strains the supply chain. The value of the brand is now tied firmly with its ability to deliver top quality. If quality falters as a consequence of the growth, the firm is likely to face unhappy customers precisely at the moment when it has an increasing number of them. So managing the production and the supply chain as demand ramps up is a critical success factor for the firm. We see this happen at an uncomfortable frequency in the Indian pharmaceutical market especially when the manufacturers are trying to expand their footprints by supply generic products overseas. A third challenge has to do with distribution. If firms have to set up their company owned distribution chains it has the benefit of exclusivity and the ability to communicate the product’s positioning very clearly. However, this comes at a cost – retail is an expensive proposition – that can undermine the value proposition of the brand. So while this might be effective in luxury retail it can be a challenge for less upmarket brands.

Photo by Vasenka

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

What’s the big deal: Flipkart, Snapdeal and the Indian e-commerce industry viewed through the lens of Twitter

With all the talk about Flipkart and Snapdeal, the e-commerce sites from India that have captured the imagination of investors, consumers and the general public with their business models and their valuations, their deals and price “wars,” and the sniping from the company’s executives, I decided to see what social media, specifically, Twitter had to say about these companies. For good measure I decided to include 3 other websites in my analysis – Infibeam, Jabong and Naaptol.

For those unfamiliar with these companies, Flipkart in May of this year (2015) raised $550 million for a valuation of $15 billion. At that time, the deal made Flipkart the third most highly valued, privately-held startup in the world. The company was launched in 2007 and today, ships over 30 million products in over 70 different product categories. The company follows a hybrid model a la Amazon.com – it sells products it inventories as well as allows other sellers to participate on its platform. Further, like Amazon, it has also launched its own private label brand. Snapdeal.com on the other hand works as online marketplace where millions of consumers can transact with over 150,000 sellers. Its assortment includes over 12 million products across 500+ diverse categories from thousands of regional, national, and international brands and retailers. It provides extensive access of sellers to buying residing in over 5000+ cities and towns in India. The company recently raised $500 million from Alibaba, Foxconn and SoftBank in addition to investors Temasek, BlackRock, Myriad and Premji Invest. This has valued the company at $5 billion.

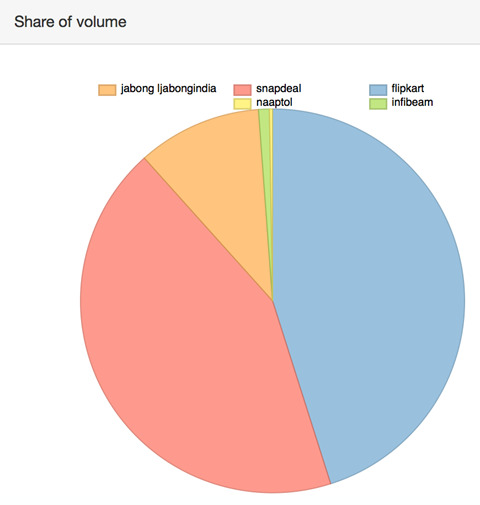

As always, I started off by looking at the relative volume of tweets involving these companies. And as always, my thanks to Yogesh Kansal for helping put the facts and figures together for this post. In Figure 1 below I show the (relative) volume of activity on Twitter from April 1, 2015 to August 31, 2015 for the 5 e-commerce sites being analyzed. The figure shows that 45% of tweets relate to Flipkart, 43% to Snapdeal with the other sites collectively garnering only about 12% of tweets. The largest of the 3 is Jabong with a 10% share.

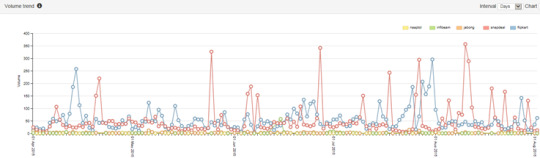

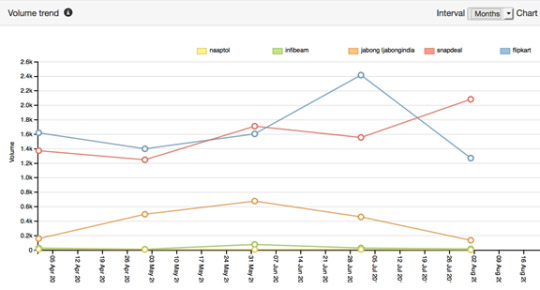

Given the similarity in overall volumes, the question is whether there is temporal variation in the tweet volumes. In Figure 2, I provide the plots of daily tweet volumes over the time period. This graph shows that while the overall numbers in Figure 1 are comparable across sites, this is not true on a daily basis. In fact, the volume shows dramatic swings for the two sites on different days. In particular, one sees big increases for Flipkart on April 14th and July 31st, the increases for Snapdeal come on May 25th, June 27th, July 27th and August 10th. Overall. The big difference in the two figures is that Flipkart shows many smaller peaks, Snapdeal’s activity seems to be concentrated more on fewer larger peaks.

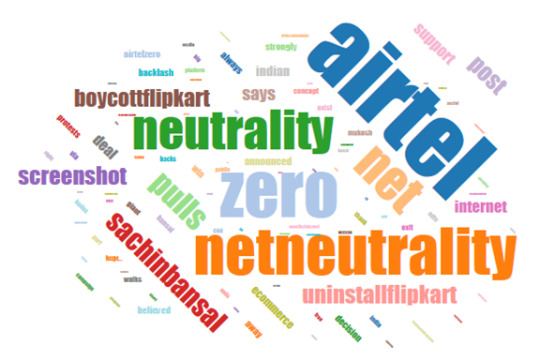

Next, one might be interested in understanding more about these peaks and what the Twitterati are saying about the companies on these days. Figure 3 shows Flipkart-related tweets on April 14th depicted in a word cloud. The figure shows that most of the action is centered around the company’s decision to support net neutrality and to walk away from a deal with Airtel Zero that would not have conformed to such a stance. This was articulated by the company’s co-founder Sachin Bansal. On the other hand, looking at the August 10th peak for Snapdeal (Figure 4) we see that none of the words is particularly dominant. The words that do stand out seem to be related to Snapdeal’s marketing activities rather than about the company itself. The August 18th word cloud on the other hand does reflect the investment from Foxconn, Alibaba etc., but also shows words like “fashion,” “products,” “contest,” etc. that all reflect the marketing activities of the firm.

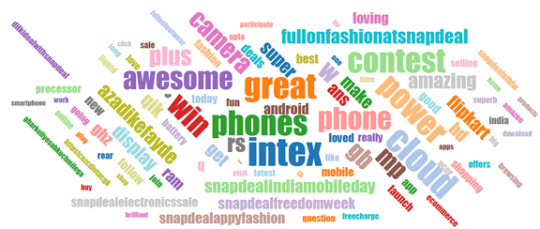

What about the overall text associated with the firms across the entire 5-month period? In the next set of figures we provide the word clouds for Flipkart, Snapdeal and for comparison, Naaptol. The results for Flipkart (Figure 5) suggest that the wordcloud we saw previously is not indicative of its entire tweet history. In particular, although words like “net neutrality” and the name of the co-founder continue to be seen, product- and marketing-related tweets appear to be more prominent – in particular, the book series Aoleon the Martian Girl is heavily reflected in the word cloud. In Snapdeal’s case (Figure 6) we continue to see a strong reflection of its marketing in the word cloud. In addition, we see emotion-laden words like “love,” “amazing,” “super,” “great” etc. reflected in the tweets. While a lot of this can be company and seller generated, the extent to which customers are expressing such feelings reflects well on the company.

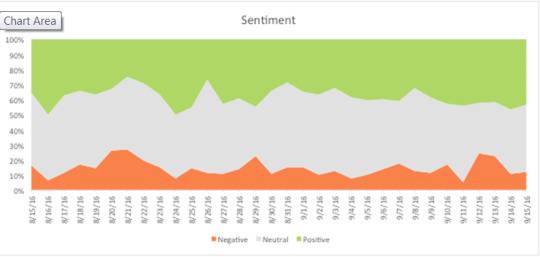

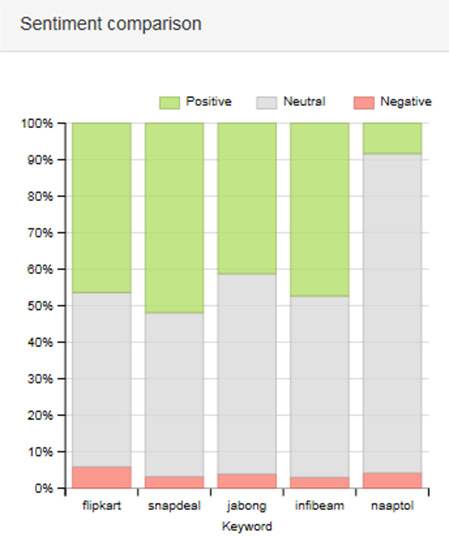

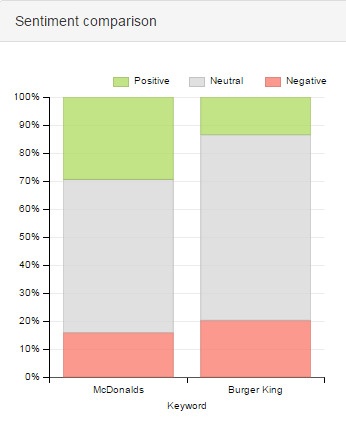

The above differences, although not large, are reflected in the overall sentiments expressed towards the companies. In Figure 7, we see that in this time period, the overall sentiments for Snapdeal are a bit more positive (52% vs. 47%) and a bit less negative (3% vs. 6%) than for Flipkart. With Naaptol we see a large range of neutral sentiment. To assess why, we look at its word cloud over the 5-month period on Figure 8. Here we see that a vast majority of words are in Hindi rather than in English. These words are not easily picked up by the sentiment dictionary leading to the neutral sentiment assessment in Figure 7.

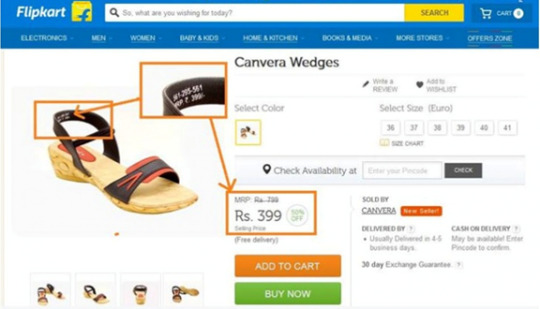

We can also dig deeper into the sentiment analysis to ascertain whether there are trouble spots for the two top players. In Figure 9 we show the word cloud for Flipkart’s June 6th Twitter activity. That day saw a spike in negative sentiment for the company. This related to the incident of the “fake discount” as shown in Figure 10 when a customer discovered that an item regularly priced at 399 Indian rupees was advertised as having a regular price of 799 which was discounted to 399 by Flipkart. So to the extent that the regular price was itself 399, consumers viewed this as a ”fake discount” – as noted by the ensuing tweets. It is clear that firms in the e-commerce space cannot afford to lose consumer confidence with such issues and the firm should guard against such recurrences. In general, though the good news is that even when there is a spike in negative sentiment for one of these companies, it is usually not associated with a concomitant spike in tweet volume, thereby indicating the limited reach of such sentiments.

While Figures 1 and 2 tell us overall volumes and the daily time series, it is hard to discern a trend for any of the firms from these figures. In the figure, Figure 11, I show the monthly aggregate tweets for the 5 players to see if any trends are visible. Figure 11 indicates that Snapdeal is showing an upward trend from April through August. Flipkart was trending up as well till July but has seen a dropoff in the last month. And Jabong rose till June but has trended down since.

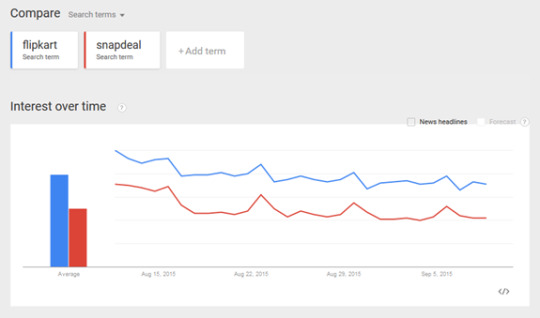

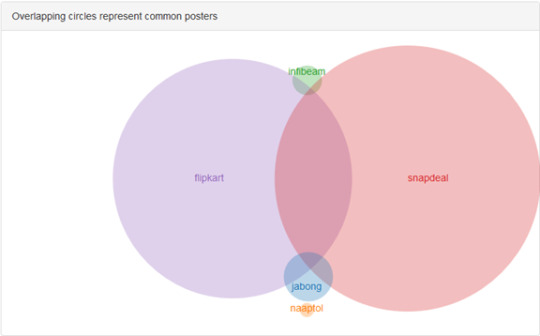

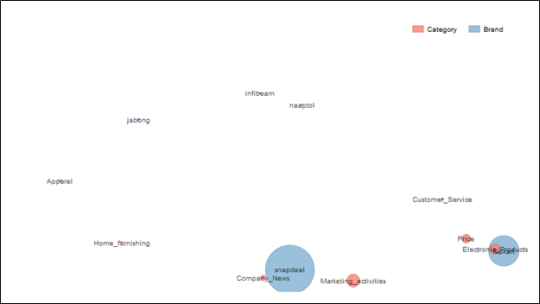

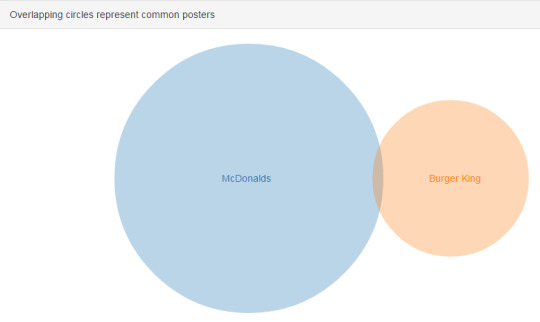

To put the information in a broader perspective, I turn to data from Google Trends. From the data in Figure 12, we can see that Flipkart is googled about 60% more than Snapdeal over the past month (August 5 to September 5). A similar pattern holds over the past 3 months and 12 months as well. Alexa rankings also suggest that website visits are much higher for Flipkart than for Snapdeal. However Figure 1 showed that the two platforms have similar tweet volumes. To get to the bottom of why this might be happening, let’s look at who and what topics the Twitterati are tweeting about when it comes to these two brands. As can be seen by the relative circle sizes in Figure 13, the number of unique posters tweeting about Flipkart is much higher than about Snapdeal over this time period. And Figure 14 shows us that tweet topics for Snapdeal for the month of August are most closely associated with marketing activities and company news as compared to the tweet topics for Flipkart which are mostly associated with electronics products and prices. While not conclusive, these findings suggest that Snapdeal’s 150,000 sellers may be using Twitter as a platform to sell their products thereby pushing up its total tweet volume beyond that of Flipkart.

I would like to reiterate that the above analysis is (a) purely qualitative in nature; and (b) does not tell us much about important outcomes such as sales. Nevertheless it is important for these growing brands to monitor their social media presence in order to avoid debilitating snafus.

Figure 1. Relative share of tweet volume April 1, 2015 – August 31, 2015

Figure 2. Daily tweet volume over time, April 1, 2015 – August 31, 2015

Figure 3. Flipkart word cloud for April 14th, 2015

Figure 4. Snapdeal word cloud for August 10th 2015

Figure 5. Flipkart word cloud for 5-month period

Figure 6. Snapdeal word cloud for 5-month period

Figure 7. Overall sentiment towards firms over 5-month period

Figure 8. Naaptol word cloud for 5-month period

Figure 9: Word cloud for June 6th negative sentiment spike for Flipkart

Figure 10. Screen shot of “fake discount” at Flipkart spikes negative sentiment

Figure 11. Monthly trends in tweet volume

Figure 12. Google search trend for the words Flipkart and Snapdeal

Figure 13. Overlap of posters tweeting about the brands. Size of a circle represents the number of unique posters tweeting about the brand

Figure 14. Topics and their associations with brands only for the month of August 2015. Proximity denotes association while size of a circle represents the volume of tweets.

Photo by Trademarks and copyrights held by Flipkart.com (www.flipkart.com) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

0 notes

Photo

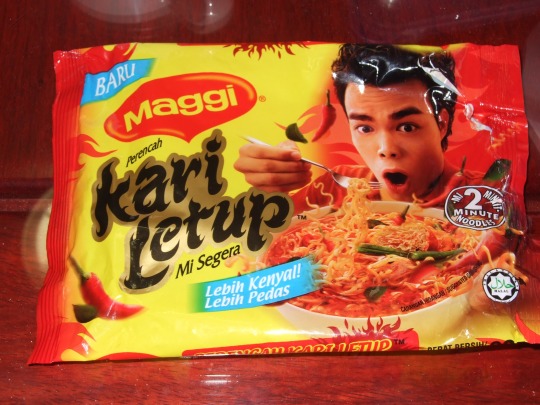

Anatomy of a scandal – How the Volkswagen episode unfolded on Twitter

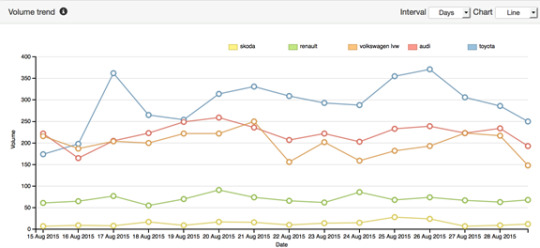

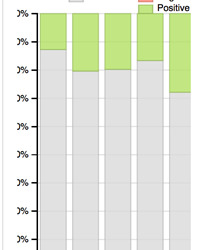

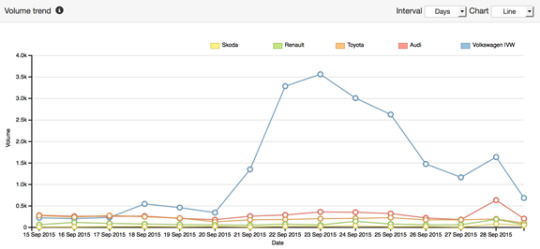

With Yogesh Kansal’s help, in this post I provide an exploratory look at the reactions on Twitter to the unfolding of the VW diesel emissions scandal. First, for purposes of comparison, I provide the tweet volume and sentiment for the period from August 15th to August 29th – one month before the period that included the revelations. This will provide a baseline for looking at the later result. Figure 1 provides the volume in that two-week period for VW along with Audi, Skoda (Audi and Skoda are also VW brands), Toyota (which was unaffected due to limited exposure to diesel engines in the US) and Renault (a European manufacturer but with exposure to diesel technology although primarily focused on Europe).

Figure 1: Tweet volume August 15 to August 29, 2015

Since the data are based on 1% of the tweets, these numbers might look small. Nevertheless the numbers are relevant when looking at them in relative terms. In August, Toyota has the highest number of tweets followed by Audi, VW, Renault and Skoda. The next figure (Figure 2) gives us a measure of the sentiments for these brands.

Figure 2: Tweet sentiment August 15 to August 29, 2015

We see from Figure 2 that Skoda (with the smallest volume in Figure 1) has the most positive (almost 30%) and least negative sentiment. In terms of positive sentiment it is followed by VW, Audi, Toyota and Renault. Audi seems to have the most negative sentiment associated with it although overall the negative sentiments are quite small. Zooming on the positive sentiment for VW, in Figure 3 we see that the trend in positive VW sentiment, if any is in the positive direction.

Figure 3: Tweet sentiment trend for VW from August 15 to August 29, 2015

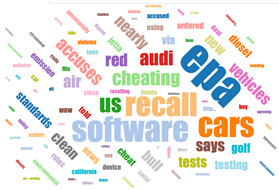

We also look at the word cloud of tweets for VW in this time range, as depicted in Figure 4 below.

Figure 4: Wordcloud of tweets for VW from August 15 to August 29, 2015

It is clear that there is no hint of the emissions problem or the diesel scandal in the month before it happened. Let us now look at what happened a month later. First we look at the volume trend.

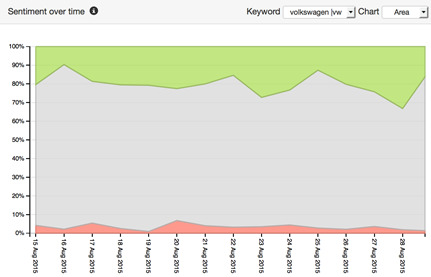

Figure 5: Tweet volume September 15 to September 29, 2015

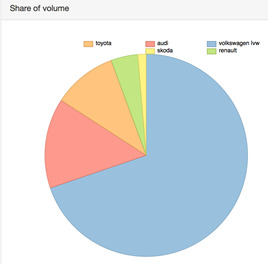

In Figure 5 we see a dramatic change in volumes of tweets across brands. VW tweets increased 17-fold by September 22nd. By comparison the tweets volumes of the other brands appear miniscule. To see this more clearly, Figure 6 summarizes the information across the time period.

Figure 6: Tweet volume (proportion) over the September 15 to September 29, 2015 period

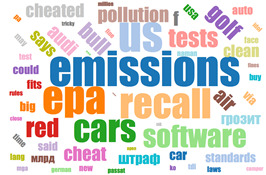

VW now accounts for 70% of tweets followed by 14% for Audi, only 10% for Toyota, 5% for Renault and 1% for Skoda. Figure 7 shows the reversal in sentiment. We see a declining trend in positive sentiment and an increasing trend of negative sentiment for VW. Figure 8 summarizes the information for the entire time period. We see that VW’s positive sentiment has shrunk to 12% from 21% with most other brands maintaining their share of positive sentiment from the previous month. We also see that negative sentiment for VW had doubled in this period.

Figure 7: Tweet sentiment trend for VW from September 15 to September 29, 2015

Figure 8: Tweet sentiment from September 15 to September 29, 2015

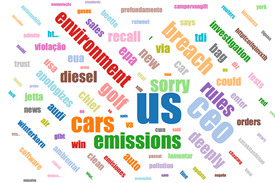

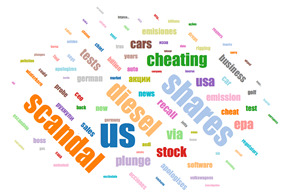

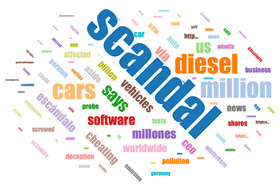

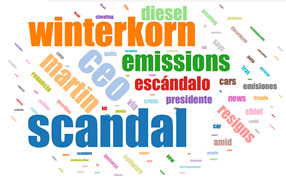

Next, we start on September 18 and track the content of tweets on a daily basis to assess how they changed in this period from an emission test result to a scandal. Figures 9(a) through 9(l). By the third day the work “scandal” started becoming more prominent in the wordcloud and this has remained the case till the 29th of September. Towards the end we also see the increasing presence of the other VW brands – Audi and Skoda. While Porsche makes an appearance this is likely due to the new CEO being from that VW group company.

Figure 9(a) September 18 – VW Tweets

Figure 9(b) September 19 – VW Tweets

Figure 9(c) September 20 – VW Tweets

Figure 9(d) September 21 – VW Tweets

Figure 9(e) September 22 – VW Tweets

Figure 9(f) September 23 – VW Tweets

Figure 9(g) September 24 – VW Tweets

Figure 9(h) September 25 – VW Tweets

Figure 9(i) September 26 – VW Tweets

Figure 9(j) September 27 – VW Tweets

Figure 9(k) September 28 – VW Tweets

Figure 9(l) September 29 – VW Tweets

The final set of figures I present have to do with the similarity between the brand in the two time periods; where similarity between 2 brands is defined based on the common words used in tweets corresponding to those brands. Figure 10(a) corresponds to the earlier period and Figure 10(b) pertains to the “scandal” period. Circle sizes represent tweet volumes.

Figure 10(a) Brand similarity August 15-29

Figure 10(b) September 15- 29

An interesting pattern emerges from the two figures. In the earlier period Toyota and VW are perceived as being similar, largely because they cater to similar customer segments. Audi is also proximal to VW due to common ownership. In the latter period however, we see that VW and Audi are bunched together with the other brands being differently perceived. There is both good and bad news for VW here. On the positive side the scandal is not yet affecting the Skoda brand; and the Audi position hasn’t changed much. The bad news however is that it is no longer perceived to be as similar to its main rival, Toyota.

Overall, we see through this exploratory study the changes in volume, sentiment, content and similarity due to the breaking of the VW scandal.

Photo by Volkswagen (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

0 notes

Photo

Volkswagen and the auto industry – Déjà vu all over again

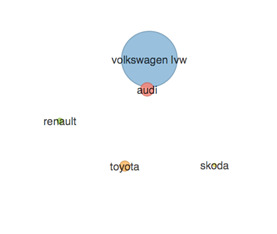

In the James Bond classic Dr. No, Bond, the character brilliantly portrayed by Sean Connery, deadpans to the title character “World domination. The same old dream.” While world domination per se might not have been on the agendas of the big car manufacturers, many of them have aspired to the top position in the auto industry, and like the fictitious Dr. No have paid a heavy price for it. In the case of the auto firms however, the price has not been fictitious and indeed has been real in terms of sales, profits and most importantly, brand reputations.

One has to go back a few decades, to the 1980s and the 1990s to trace the decline of the longtime market share leader, General Motors. Figure 1, excerpted from Mannering and Winston (1991, Brooking papers), shows how that company lost share over time – with a high of almost 50% in 1979 to the mid-30s by 1989. In large part this decline is attributed to the organization’s hubris. As the Economist magazine noted in 1998, “ALL empires contain the seeds of their own destruction. The ideas on which they were founded cannot adapt to changing times. Their wealth creates bureaucracy and complacency…. GM pops up in management books only as an example of what not to do—blamed for not introducing products quickly enough, for poor labor relations and so on.” The Japanese manufacturers led by Toyota, Honda and Nissan marched forward armed with concepts like total quality management and continuous improvement to gradually raise their share in the US market. By not focusing on their customers, employees and other stakeholders, GM squandered the brand loyalty and reputation that it had taken for granted. The result- losing market share and eventually, profits.