Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The Lure of Five Phase Acupuncture

I remember my first encounter with five phase acupuncture. I had enrolled in some informal classes with a local Chinese doctor, Wu Shicun, which were held in a small room in his shop on Clark Street in Chicago. The room was between his apothecary storefront and his Taiji class space in the back. Doctor Wu sat at a little desk and we crowded into the chairs around. Behind him was a dusty blackboard. I’d already studied with him for several months and had absorbed the basic theories and acupuncture point information. We’d learned all about the organ functions, qi-blood-fluids, fundamental physiology and pathology, and the point indications. Everything seemed logical and made sense so far. Then, we had an introduction to the Mother-Son principle of point selection from Chapter 69 of the Nan Jing. If Lung Metal was deficient, strengthen Spleen Earth and the Earth point of Lung Metal, and drain Heart Fire and the Fire point of Metal. If Lung Metal was excess (say, Lung Heat), strengthen Heart Fire and the Fire point of Lung Metal, and Drain Kidney Water and the Water point of Lung Metal.

It made no sense in the context that we’d learned before. Why would you strengthen Fire and drain Water in a heat pattern? It all just seemed too far out and abstract. One of my classmates blurted out, “Do you actually use this?” “Sometimes, yeah,” nodded Doctor Wu.

For my part, something about it just lit me up. I had to learn more. My natural response was to seek out further reading on the subject. Doctor Wu had a copy of the treasure trove of delights that was the Redwing Books catalog, and I thumbed through it. There was a book that looked promising: Five Elements, Ten Stems. I soon had a copy in my hands and dug in. That was it for me.

I will spare you the details of my astrological chart, but suffice it to say that as a Scorpio-heavy individual, I have always been attracted to the more arcane side of any discipline, and acupuncture was no exception. Something about the Mother-Son principle I learned in that particular lecture opened a door to a world where magick was an operational reality, where I could unlock a whole system of correspondence that existed in some archetypal realm and actually produce a concrete result. It was like bringing down the Heavens onto Earth.

Twenty-nine years later, I haven’t lost that sense of wonder. My fascination hasn’t waned. Five-phase theory is still the main organizing principle of my treatments. I bend the rules, of course, but it still feels a little strange when I do. Even then, I know the terrain well enough to rationalize my little departures into layers: Five-phase with underlying Extra Vessels, and an overlay of qi-blood-fluids, or synced up with Four Levels for example. It’s always in there somewhere.

Five Elements, Ten Stems set me off on another quest as well. Beyond the theory and the cosmology, there was the matter of the treatment methods. From the pages sprang forth an almost mythical pantheon of healers from Japan who used tools made of precious metals, and who were able to use “scratching and flicking” techniques to rectify the imbalanced Elements; these guys were so hot they didn’t even need to insert the needles. If there was any penetration, it was on a micro level; insertion depth was a few millimeters as opposed to the 2 and 3 inch stabs we studied in the Shanghai manual.

This was SO what I signed on for.

I sought out more instruction as a student in acupuncture college, despite the ribbing I took from my TCM-oriented instructors. I managed to find mentors and attended as many seminars as I could, in the US and Japan. I knew that early influences tend to stick much better than later ones, and no matter what other styles or techniques might catch my interest in the ensuing years, Japanese Five-Phase acupuncture (formally known as Keiraku Chiryo, Meridian Therapy) would always be the home base to which I would return.

Robert Hayden, MSOM, AP, LAc

1 note

·

View note

Text

Pulse Feedback Test (PFT)

One of the things I struggled with for years in adapting my JMT training to a CA context was what to do with pulse diagnosis. More specifically, what to do with Six-Position pulse diagnosis, since that is what proved to be most challenging. Instead of standing over a patient on a table, I was sitting in a rolling stool next to a reclining chair. The body mechanics involved in taking pulses at both wrists simultaneously was awkward, and taking one wrist at a time involved rolling around to the other side of the chair. Since in most cases I have about 5 minutes to decide what to treat and get all the needles in, this was clearly not going to work. I had already given up on abdominal diagnosis and extensive meridian palpation as impractical. This left me with only symptom analysis to determine the sho, which felt incomplete in many instances.

The solution was to abandon six-position pulse diagnosis in favor of what I call the Pulse Feedback Test or PFT. This is not something I invented; it is based on the methods I learned for checking point location and needle technique among the blind acupuncturists. One of them mentioned using it as an auxiliary method of choosing Extra Vessels. I just adopted it to help determine the Sho.

PFT is similar to using the VAS (Vascular Autonomic Signal) in French auriculotherapy, or to AK (Applied Kinesiology) in chiropractic and related fields. You take the pulse at one wrist, and note the quality. You apply a particular stimulus to test a Sho, and look for changes in the pulse.

I have been trying this out for a few years now, and I continually develop the method based on what I was taught, what I read about related methods like AK, and most importantly what works better for me in my clinic. At present, the method looks like this:

1) Find the radial pulse. Position your fingers at the depth where you feel the pulse most clearly - superficial or deep, doesn’t matter. You can use one finger if you need to. Notice the depth, rate, volume, clarity and force of the pulse. Ask yourself what aspect of the pulse quality needs to improve: is it too fast, too superficial, unclear, weak?

2) Go through each of the Sho, one by one. Note if the pulse changes, and how. How do you do this? In the beginning, I just thought to myself the name of each Sho: Lung, Spleen, Liver, Kidney, Heart. I found this to be a little too hazy - maybe my own lack of focus - so I started to touch a point on each of the five meridians. This works much better for me. In general I use the Yuan-Source points. Note that when you are taking pulses you are already touching the Yuan-Source point for the Lung, so I will use another point, usually LU5 or LU6. I can already hear the objections from the purists: But LU5 is the draining point! OK fine, then stroke the channel a couple of times from LU5 to LU6 if it bothers you.

3) In general, you want some aspect of the pulse to improve. Often it is the rate or the force; I.e. the pulse slows down or becomes a little softer or firmer relative to what it was in the first place. If more than one meridian produces a change, compare those two and see which gives the best quality or most pronounced change. If the result matches whatever Sho the patient’s signs and symptoms would suggest, you’re good to go. If not, then you have to choose. In my mind, if the pulse change is very clear, especially on rechecking the pulse, that’s what I will usually treat. If the pulse changes are not so clear, then I will usually just go with the signs and symptoms.

In the beginning, I found this method to be a little more time-consuming than I would have liked. However, I was interested enough in it to keep working with it and now it takes very little time. On return visits, if the patient has reported improvement, I am likely to just repeat the treatment.

0 notes

Text

Six Position Pulse Diagnosis

I’m going to give you the basics on this, as it is the most common method of determining sho in JMT. Personally, I use it far less often than the Feedback Method, but it’s good to know both.

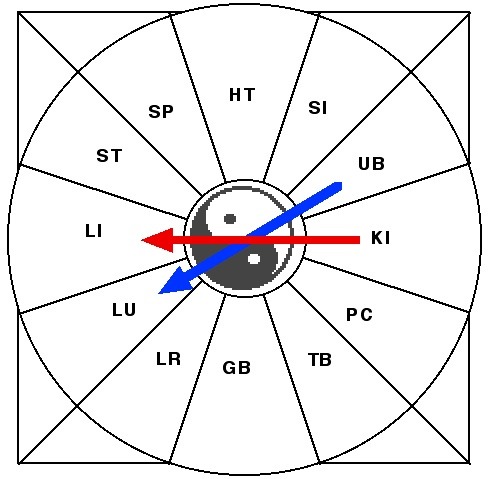

Here are the pulse positions based on Chapter 18 of Nan Jing. The outer circles represent the superficial (Yang) positions and the inner the deep (Yin) positions.

For purposes of determining the Sho, we are really only concerned with the Yin level.

Comparing Pulses Using Generating and Control Cycles

If you look closely at the pulse positions, you can see that they follow a sort of pattern with regard to the Generating and Control cycles of the Five Phases. The generating cycle follows each wrist from proximal to distal pulse position, and between both wrists makes a sort of infinity symbol:

The Control cycle shows up as a kind of zigzag between the pulse positions on the wrist:

The most efficient way to do this comparative examination is to take the pulses at both wrists simultaneously. This is commonly done with the patient lying supine (face-up) on a table. I find this awkward to do with the patient in a chair, so I generally take each wrist separately, note what I find, and line everything up mentally. I practiced for many years on tables, though, and I think the years of experience has made it easier to do it this way.

When comparing pulse positions, you are looking for the most deficient (usually weakest) position on the Yin level. However, one pulse position does not a Sho make; rather, the pattern of two deficient Yin pulse positions along the Generating Cycle (I.e., Mother-Child) is the major diagnostic indicator. If one finds a noticeably deficient pulse position, it will likely be part of the Sho. The only thing one needs to figure out is whether it is the position of the Mother or the Child. So, rather than go through every pulse position comparing each to one or two others, a much quicker way to answer this question is to compare the Mother and Child of the most deficient position. It may be easier to illustrate with an example.

After finding the radial pulse, you sink your fingers to the Yin level. You are looking for the most deficient pulse position.

As you sink your fingers, you notice that the left proximal pulse (Kidney) disappears before the others and feels weak. So the Kidney, you surmise, must be part of the Sho.

You then check the left middle position (Liver, the Child of Kidney) against the right distal position (Lung, the Mother of Kidney).

You decide that the Liver position feels a little more empty than the Lung.

Thus you have a Liver Sho, since the Liver and Kidney are deficient together along the Generating Cycle. This is the case even though the Kidney feels more deficient; this is because the Sho is named for the Child. Had the Lung been weaker than the Liver, the Sho would have been designated a Kidney Sho, since the Lung is the Mother and the Kidney is the Child in the relationship between those two organs.

Deficiency and Excess

When we talk about comparing pulse positions, we usually start with teaching that deficient pulses are weak while excess pulses are strong. But this is not always the case. Another concept one should consider is that the normal pulse should evince a quality known as “Stomach Qi”. This quality is a sort of springy resilience, not too hard and not too soft, not too fast and not too slow. The fluid wave should be felt but not too gushing, it should have the fluid quality but not feel too squishy. It should feel “consolidated” - the term in Japanese I heard associated with it was “hosoii”, which technically means “thin”, but “consolidated” was the translator’s choice - since the Stomach is Earth and part of Earth’s function is holding things together, the boundaries of the vessel should be clear. The pulse should not feel like it is sort of leaking to the side or squishing outside the boundaries of the vessel. At the same time, the boundaries should be supple and not hard, but still holding the vessel’s shape. If it does not hold shape, or one feels this squishy, leaky quality, then the pulse is considered to be one of deficiency, even if it is otherwise palpable. It could feel “big” but still be deficient; the amorphousness of the wave is the key to determining deficiency in this case. When comparing two pulse positions, one may feel “bigger” than another and thus it is easy to mistake this for excess in the “bigger” pulse; the “thinner” pulse position may in fact be a normal pulse wave that has Stomach Qi where the “bigger” pulse is actually the deficient position. This is something that is important to understand but difficult to teach the beginner.

Qualities in Positions In addition to the overall pulse quality, you may feel different qualities in each of the positions. For example, the Heart position may feel thin or the Lung pulse may feel choppy. These individual qualities will usually improve with the treatment, and in my opinion, as a beginner you shouldn’t be overly concerned with each quality in each position. When starting out, the best thing to focus on is determining which of the positions feels weakest, and looking for correlations between the weak or strong positions according to the Generating or Control cycles. I was taught to go back to the pulse repeatedly to look for aberrant qualities in the different positions, and apply various needle techniques to correct them; frankly this led to a lot of frustration and wasted time. It may come down to philosophy, but I have come to think that the most important priority is to help the body expel pathogens and restore balance on its own.

0 notes

Text

Pulse Quality

Once you find the radial pulse, the first thing you are looking to determine is the pulse quality. Pulse quality is important in many respects - it can give an indication of the state of health and constitution in general, and how to proceed in treatment. It can also serve as feedback, which is a characteristic of Japanese acupuncture in general; you want to notice if and how the pulse has changed by means of your treatment. Once the quality is noted, the examination can proceed to feeling the pulse underneath each individual finger, which is what we refer to as “six-position” pulse diagnosis.

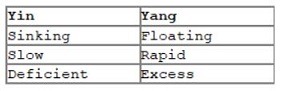

There are six basic qualities we look for in pulse-taking, arranged in Yin-Yang pairs:

A good pulse shows a balance between all of these qualities. The pulse can be felt most clearly in the medium depth, is of a moderate speed and has a calm, harmonious quality with a healthy resilience and no hardness.

Basically, to summarize the process: Place your fingers along the radial artery to locate the pulse. I was taught to locate the styloid process (LU8) with my middle finger, then place my index and ring fingers alongside the middle finger. Shift your fingers off the bone toward the meat of the medial forearm and feel for the pulsation of the radial artery.

Press your three fingers (I use the pads, though some use the tips) into the flesh slightly until you feel the pulse. Get a feel for how much you need to push in to feel it clearly, or if it gets weaker as you press. If you don’t start to feel the pulse until you’ve applied a lot of pressure, you would say that the pulse is more sinking, or deep. If you feel it strongly near the surface, but it disappears quickly as you press, then it would be more floating, or superficial. You may need to slowly press your fingers in and the slowly lift them up a few times to get a feel for where the middle depth lies.

Speed is a relative thing, and the usual advice from the classics is 3 beats per breath cycle as the norm. Smaller people, like children and petite sized men and women, will have a faster pulse than someone larger. Generally fast pulses indicate heat and slow pulses indicate cold. This may influence your choice of points; for example, you may decide to treat fire or water points on the affected meridians if the pulses are very rapid or very slow. Some medications can affect pulse speed as well, so it is worth asking what medications the patient may be taking when you make the initial consultation.

Deficiency and excess are a little more subtle. The usual advice for beginners is that a soft pulse is more of a deficiency pulse and a hard pulse is more of an excess pulse. This is not always the case, but as a starting place, it is good enough. One of my teachers told me that an excess pulse is “coming” and a deficiency pulse is “going”. An excess pulse rises up to meet your fingers, and puts up a fight against you as you apply pressure on it. A deficiency pulse does the opposite: it lays down or runs away.

When noting the pulse qualities above, we are establishing a baseline. This is important in the pulse feedback method, which we will discuss shortly.

0 notes

Text

The Sho

JMT is founded on Five Phase theory, specifically as it was laid out in the Classic of Difficulties (Nan Jing). For those who might not remember (or to whom all of this is new), the Nan Jing is a late Han period text that gave us, among other things, six-position pulse examination and the Mother-Child principle. It was also the beginning of pattern diagnosis, in that it gives in Chapter 16 a system for diagnosing diseases in the Yin organs by linking symptoms with pulses and abdominal palpation.

These five Yin organ patterns (called Sho in Japanese) were adopted and expanded upon by the acupuncturists who developed JMT. They combined the six-position pulses from another chapter and meridian/point selection and needle techniques from some others, and started treating people with that as their foundation. As time went on, they adapted further details depending on their clinical experience, but the basis in Nan Jing Five Phases remained intact.

The Nan Jing focuses its discussion on pathology almost exclusively on the Yin organs. Though the Yin organs can be affected by Deficiency or Excess, the Deficiency conditions are considered to be the fundamental cause for disease. Yin organs are known as Zang in Chinese (Zo in Japanese), which indicates that their primary function is to store Essence in various forms; if their storage is sufficient, illness will not arise in the body. So the root of all pathology is seen as Deficiency in one or more of the Yin organs.

One of the variances from the original theory occurred early on in the development of JMT: the Sho for the Heart was dropped. This stems from the idea that if the Heart becomes Deficient, the situation is too grave to treat with acupuncture - because the Heart stores the Shen, or Spirit, and in the Hung Di Nei Jing it says that "When the Spirit is lost, the patient will perish". So the founders of JMT started with Four Sho.

Applying the Mother-Child principle from Nan Jing Chapter 69, which says that when an organ is Deficient, its Mother (the organ corresponding to the Phase preceding it on the Generating cycle) is also Deficient, JMT proposes a diagnostic framework of four Sho:

Lung Sho: Lung and Spleen are Deficient Spleen Sho: Spleen and Heart (usually Pericardium, in practice) are Deficient Liver Sho: Liver and Kidney are Deficient Kidney Sho: Kidney and Lung are Deficient

As JMT has evolved in the 80 or so years since it was started, different leaders of the school have postulated ways to extend this model. The Four-Sho basis, however, remains more or less constant. I remember a conversation regarding the idea of a Heart Sho with one of the most highly-regarded JMT practitioners; he admitted that while it does show up clinically, the Four-Sho system works well enough and an additional Sho needlessly complicates things. Personally, I do treat the Heart/PC Sho (Heart/PC and Liver are Deficient) and find it very useful but I am in the minority as far as that goes.

What of the Yang organs and meridians? There is no majority consensus. Some say they follow the same rules as Yin organs and meridians, some say they follow different rules, some say they follow no rules at all. We will discuss that in another chapter.

0 notes

Text

Transitioning to Community Acupuncture

By the time this book is published, there will probably be little need for an extensive description of Community Acupuncture (CA). It has been more than ten years since the practice model, created at Working Class Acupuncture in Portland, Oregon, began to propagate via the internet. The means by which it spread was the Community Acupuncture Network (CAN), which I joined in 2006, if memory serves. I was primarily teaching Chinese medicine at the time and had a very small private practice. Since I was the herbal medicine instructor at the Academy for Five Element Acupuncture around that period, a good chunk of my client list came to me for custom granule herb formulas. I was charging about half of my office colleague's fee for acupuncture, but I was not very busy. After participating in the CAN forums, I decided I had little to lose in switching over to CA. In 2008, I opened Presence Community Acupuncture. The original space was structured as what's known as a "hybrid" model. I had a small room with a table and a somewhat larger room with four recliners (later three recliners and a table). The dual fee structure didn't last long, and I rather quickly drifted into CA-only pricing. The result was that private room treatments with CA fees became a common occurrence in my clinic, and scheduling the table treatments was a serious headache. In addition, walk-ins were problematic due to lack of seating capacity. After a few years, I moved to a bigger space and, eventually, got rid of the tables altogether. The years between starting the clinic and ditching the tables had seen a gradual re-evaluation and pruning of the tools and techniques I had relied on for my 14 year career. Mainstays like direct moxibustion, intradermal needles, ion-pumping cords and electrical stimulation grew unwieldy as the schedule filled up, and were slowly abandoned. The treatments had to be done with filiform needles and perhaps some ear seeds. Complex diagnostic processes with frequent re-checking proved unworkable, and customized granule prescriptions gave way to teapills. I was learning, day by day, what was really essential in my treatment philosophy and methods. The ever increasing caseload demanded both efficiency and efficacy. Establishing a chairs-only policy in particular represented a sort of milestone. Back pain, sciatica, neck and scapular pain are all bread-and-butter cases in an acupuncture clinic. Limb pain, headaches, psycho-emotional and internal complaints are all readily treated by points accessible on a seated patient, but I had to learn and develop ways in which to address areas that I couldn't needle directly. Techniques for this have been available since acupuncture began, of course, but I needed to make sense of it within the diagnostic parameters I had adopted; I also needed to feel that I could rely on the methods, which entails accumulation of clinical experience with them. At present, I have come to the point where I have a reasonably consistent and workable system for treating patients in a CA context. My understanding and skills continue to be refined, of course, but the structure has been established and seldom are the instances when someone comes in the door with a complaint that I have no clue as to how to proceed. The fruits of this long growth process are summarized in this series of short books. Book One outlines the theories and diagnosis patterns. Book Two is dedicated to treatment, both in general and specific strategies for commonly seen conditions. Book Three is a summary of acupuncture points that I use with my commentary on each of them.

0 notes

Text

Japanese Acupuncture As A Brand: Some Background

In virtually any discussion about types of acupuncture available in America, one of those named will be "Japanese acupuncture". When described, "Japanese acupuncture" is generally assigned many the following characteristics: gentle, subtle, thin needles, shallow insertion, non-insertion, guide tubes, and so forth. While the attribution is not entirely incorrect , it is not categorically true, either. Japan is home to a broad array of acupuncture theories and techniques; in fact, their educational requirements encourage the majority of practitioners to utilize a scientific rationale and practice a more physiotherapy-oriented variety than is common in the West. However, largely due to the publication of numerous texts in English highlighting neo-classical styles, mostly in the late 1980's and early 1990's, the Western perception of "Japanese acupuncture" as being a soft, "energetic" art has stuck.

At the outset of the Twentieth Century, Western science-based medicine eclipsed its traditional counterpart everywhere in Asia. Acupuncture, while still employed in Japan, was taught using a sort of grid scheme and the classical concepts of meridian circulation, tonification and draining, et cetera, were discarded. In the twenties, a jujitsu expert, Sawada Takeshi (aka Sawada Ken) had been studying an old book on point location he'd picked up in Korea and applied the treatments there employing direct moxibustion to apparently wondrous effect. After a much-heralded homecoming to Japan, he became the inspiration of other acupuncturists who sought to "Return to the Classics", a phrase which served as their motto.

This historical period roughly coincides with China's reappraisal of its own medical traditions and the subsequent compilation and systematization of what came to be known as Traditional Chinese Medicine or TCM. However, the two systems grew to have decidedly distinct foci. TCM took much of its theoretical basis from herbology. In the effort to produce a unified system of diagnosis and treatment, acupuncture, under the influence of famous doctors such as Wang Le Ting, was shaped to fit the principles created to compose herb formulas. In Japan, herbal medicine (Kampo) was kept separate from acupuncture and the methods outlined in the Nan Jing (Classic of Difficulties) took on a prominent position in the creation of the neo-Classical movement, which was dubbed Meridian Therapy (Keiraku Chiryo) to highlight the reinstatement of the meridians as a foundational principle.

This is a very simplified view of the history of the subject. More "acupuncturistic" methodologies, often handed down through families, continued to be used in China and Taiwan; some, such as that of Master Tung, have become well-known in recent decades. Likewise, indigenous varieties not based so much on the classics have thrived in areas such as the Kansai district (I had the pleasure of some tutelage in one of these, the Taishihari Ryu of the Tanioka family in Osaka). But the major distinction between TCM and Japanese Meridian Therapy (hereafter abbreviated JMT) still holds true.

When I was a student in the mid-1990's, Japanese styles were becoming better known because of the books by Kiiko Matsumoto and Stephen Birch. Many highly-regarded senior teachers came to the US to teach, and a significant subsector of acupuncturists grew interested in JMT. Its presence in the US peaked somewhere in the early 2000's, and waned in the wake of the surge in popularity of Richard Tan, Jeffrey Yuen and others, along with the growing number of adherents of the Tung school. What goes around comes around, though, and recently I have seen indications of renewed interest in JMT.

0 notes

Text

Intro

I've been chipping away at this material for a while now. I struggle with the motivation to finish; if I figure nobody's going to read it, why put in the effort? A few weeks back, I had a conversation with a graduate of AFEA. She wanted to send a patient to me. I talked to her for a while. She mentioned that she thought community acupuncture was great, and she'd like to try it, but she couldn't see how she could make the transition. It wasn't really an issue with the business systems; it was the way she was trained to practice, the Worsley Five Element diagnostic and treatment methods she relied on every day. After the call was over, I thought: There's a good reason to put the book out. When you transition to a very different practice model, what do you do about the way you diagnose and treat? So far, the preponderance of advice you'll see among community acupuncture people is to ditch your training. Go take a Balance Method class. And that's fine, most people do that. I didn't. I don't care to push someone else's brand, frankly. I like the way I treat, and I was interested in how much of it I could apply, what would work and what wouldn't. I came from the world of creative arts, rather than medicine or martial arts or any of the other usual trajectories which bring people to acupuncture school. I like to take something and shape it, refine it, to reflect what is vital, what is sacred and holy to me, to make it sing with my voice. Shudo Denmei sensei inscribed my copy of his Meridian Therapy book with the phrase "Hari wa Hito Nari", meaning Acupuncture is the person who does it, it becomes a true reflection of who they are as a human being. I took this as my motto for years, without understanding its significance. I believe I am closer today than I have been any time during the last couple of decades. What do I want from people who read this stuff? Do I want people to study it assiduously and begin applying it in their clinics? Well, sure, if it speaks to you that way. I happen to think the Sho system is a great middle ground between the sort of universal protocols (NADA, ML10, WCA Soup Stock) and the 120 or so TCM patterns. It's pragmatic and flexible, being used daily in high volume practices in Japan. But maybe more important is giving an example of how I have adapted the techniques and methods I've used for my whole career to work in a radically different context. Something I sweated and struggled over, and felt enough passion and commitment to keep returning to develop. If my work inspires you to do something similar in your own life, maybe better still. As the saying goes, don't follow in the footsteps of the masters, rather seek what they sought.

0 notes

Photo

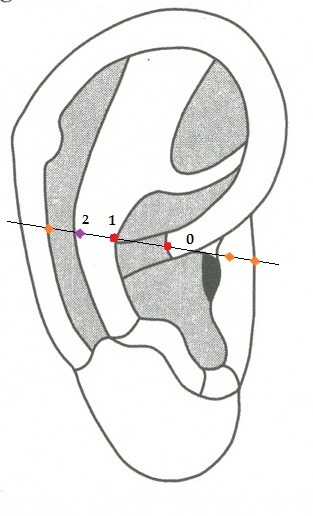

There was a discussion in one of the few acupuncture groups i post to regarding this article: http://www.foxnews.com/health/2012/09/21/doctor-injection-can-cure-ptsd-in-veterans/ The discussion centered on an alternative method to stellate ganglion nerve block for PTSD. My speculation (and that's all it is at this point) was that the Stellate Ganglion auricular point (in red, labeled 1 in the diagram below) may be useful - it is used a lot in auriculotherapy as part of the treatment of a First Rib blockage, in which malposition of the first rib can cause irritation to the stellate ganglion and cause a lot of chronic upper body symptoms. If the ear point can relieve irritation on the SG, then theoretically it should be similar to a nerve block. Other points along the line between SG and Point Zero (in red, labeled 0), including the First Rib (labeled 2, in purple), may also be used if reactive (or if you just want to hedge your bets - examples are in orange and unnumbered). Other possible points that occur to me are points along the SCM and scalenes - ST11,12, 13, some of the Windows of Heaven points, K27 which directly treats the first rib.

Again, this is speculation but seems worth trying before letting an MD crank a hypodermic into somebody's neck.

(cross-posted from my Facebook page)

1 note

·

View note

Link

The post title is a link to my major paper from acupuncture college, on treatment staging in Japanese acupuncture. I reconstructed it from a text file, most of the tables and diagrams had been lost. Posted to my Scribd page.

0 notes

Link

This blog discusses acupuncture points. If you are unfamiliar with the locations of these points, take a look at Qi Journal's online acupuncture point locator. Just click on the title of this post.

Another more detailed source is found here:

http://www.yinyanghouse.com/acupuncturepoints/locations_theory_and_clinical_applications

1 note

·

View note

Text

Access to Meridian Levels through Points

Access to Meridian Levels through Points

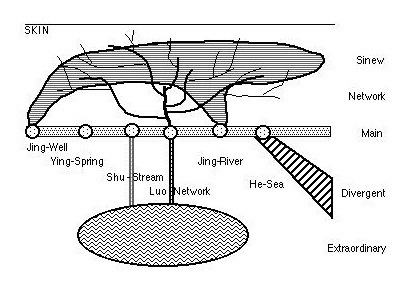

n.b: a continuation of the previous post

Meridian Levels are accessible through certain key points where they intersect the Main Meridian. This concept is shown in the following diagram. While some point associations are explicitly stated in classical materials, others are not and there are some differences in interpretation. For example, the access points for the extraordinary vessels and network vessels have been defined explicitly. The meridian sinews are said to start at the ends of the fingers and toes and bind at the ankles and wrists; the interpretation is that they intersect the well points (which coincide almost without exception to the ends of the fingers and toes) and bind at the river points (which are mostly found at the wrists and ankles). The divergent meridians are said to begin at or above the knees and elbows; the interpretation by some authors is that the closest essential point to these areas, the sea point, is used.

The extraordinary vessels are properly said to be accessed through their confluent (master-coupled) point, but they are represented here as being accessed at the network or stream points. This is because, of the eight points considered, half are network points (LU7, SP4, P6, TB5) and another two are stream points (SI3, GB41). The Yinqiao vessel is accessed at K6, which in our method is found in virtually the same location as Sawada’s K3 (Taikei), giving it an “almost-stream-point” status.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Japanese Meridian Energetics: an introduction

Japanese Meridian Energetics: an introduction

n.b.: This is from a handout i made for a course i taught at a shiatsu school long ago.

The Meridian System

The Meridian system is composed of five basic levels:

The MAIN MERIDIANS, which are the twelve bilateral pathways named for the Zang-Fu on which the bulk of the acupuncture points commonly studied are located. There are various ways in which to organize and classify these meridians, such as Five-Phase, Three-Yin-Three-Yang, or Midnight-Noon principles. They have a variety of functions, but the most important is the function of connecting the Zang-Fu with each other and the rest of the body.

The EXTRAORDINARY VESSELS, which are the deepest of the body’s energetic pathways, associated with structural balance (bone level), constitution and general functional regulation. They are separate from the main meridians, though they intersect the main meridians at a number of points.

The MERIDIAN SINEWS, which are the most superficial pathways of the system, associated with movement, muscle balance and defense. They too are separate from the main meridians, though they intersect the main meridians at the Jing-Well points.

The NETWORK VESSELS, which branch off from the main meridians and run to the surface of the skin as well as connecting paired main meridians. They may be considered as superficial branches of the main meridians.

The DIVERGENT MERIDIANS, which branch off from the main meridians and connect paired meridians at a deep level as well as strengthening the connection between Yin main meridians and the head. They may be considered deep branches of the main meridians.

A schematic of the Meridian system might look something like this:

The Meridian levels at which we will be working are the first three mentioned here: the Main meridians, the Extraordinary Vessels and the Meridian Sinews. The Network and Divergent levels function largely as branches of the main meridians and can be influenced to some extent by treating the other three levels.

In addition to the three (superficial, organ and bone) levels, another level will be taught: this is the level of the undifferentiated whole (Taiji or Taikyoku), which can be employed either for general systems regulation before any pathology affects the body, or when the pathology is too extensive and difficult to isolate to one level or one meridian.

All of these Meridian systems are mentioned in the earliest classics, but details of their treatment varies from extensive to sketchy. Much has been written about the meridian systems since then and much more has undoubtedly been lost over the milennia since the Huang Di Nei Jing was compiled. At various times during the history of acupuncture, revivalist movements have sprung up attempting to codify diagnostic and treatment techniques to effectively treat these pathways.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

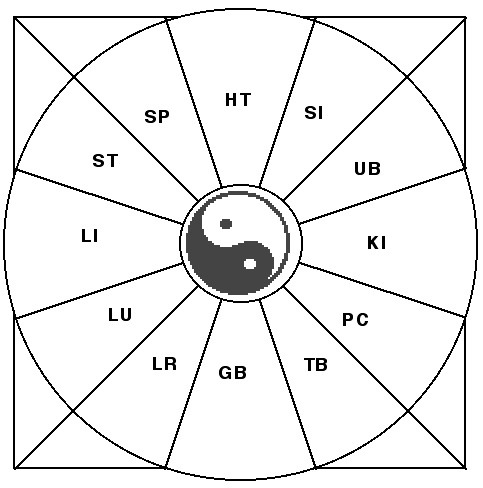

Shigo Chiryo (Midnight-Noon Therapy) How to use this clinically? Say a person comes in with back pain along the UB channel. In situations where you may not want to needle the back, you can select the channel opposite on the wheel. Needle the cleft point or find tender points along the opposite channel (here the LU channel) on the contralateral side of the pain. If there is a chronic aspect to it (KI channel), you can further add points from the LI channel. I was taught this years ago when studying with a well-known Japanese meridian therapy organization (whose name i won't mention). It is also one of Richard Tan's Balance Method systems, and something i use on a daily basis in the clinic. I've seen some pretty remarkable results with it.

0 notes