Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

I love the points you made about identity in this movie. I talked a lot about how capitalism changes people, and your points on names and faces is perfectly aligned with that. The changing of names of having different names in the bathhouse vs. outside of it encapsulates perfectly how the characters are affected by capitalist society. Zeniba's ultra-greedy, power-hungry name is Yubaba, the Kohaku river being filled with apartments and controlled by Yubaba is named Haku, and No-Face, not really having an identity, like you said, takes on an insatiable hunger and careless throwing around of wealth inside the bathhouse, speaking for the first time there. Chihiro's name is interesting though, because while she works at the bathhouse and therefore plays along in society, she doesn't forget her real name, and is therefore still able to do good there, saving the river spirit that was plagued with pollution and leading No-Face out of the bathhouse so that he couldn't consume anymore people. Great analysis!

Spirited Away

It feels unusual to look at a childhood film with academic eyes but here goes nothing.

The way this film handles identity is really interesting to me! For Chihiro and Kohaku, this takes the form of names. By having your name forcibly taken from you or forgotten, you lose your sense of self and become vulnerable to other people. Not only do you lose yourself but you lose your home as well. Although signing the contract is essential for her to continue existing in the spirit world and find her parents, it also means giving away her name and sense of self. She now needs to keep safe her identity and keep a hold of herself as much as she can. To me, this also manifests as the need to be confident in one's self. Kohaku tells Chihiro she needs to keep asking for work and Chihiro does persist even when Yubaba is in her face. In other words, Chihiro must learn how to look confident, stand her ground, and remain dedicated to her goals. And she does the whole film through! Kohaku does much the same especially when he takes hold of himself again after the bug controlling him is squashed, revealing to Yubaba the disappearance of her precious baby. About the being unable to go home part, I'm not sure what to make of it but only that losing your name cuts your connections to your previous life. I guess in that sense you no longer remember home or where it is.

No Face is another example of identity too. Without a face, do you have an identity? Not only for us humans but the creatures of the film are each unique in some way. If not by face, then by personality but how do you express personality? Generally it is by speaking. No Face has no mask and constantly struggles to speak unless he's stolen someone else's voice (like the frog's). In that sense, No Face is unable to express his identity and therefore has no identity at all. Chihiro must interpret by his actions, by his few words, and by her own sense of kindness. The scene where she notices No Face following her to the bus, she asks him if he is and he doesn't really reply. But she is happy to use one of her tickets for him. I think that's why he gets along with Zaniba at the end of the film. She is also kind and gives him a home and good work to do.

Identity is also sort of tied to form at least in other people perceive someone's identity. Yubaba and Zaniba share an appearance so that Bo and Chihiro are caught off guard by Zaniba's appearance and actions. However, the two are so obviously different from each other. Chihiro must stand up to Yubaba but she is grateful and hugs Zaniba. Bo is spoiled by his mother but then stands up to her. He is at first bullied and taught a lesson by Zaniba but it is because of Zaniba that he learns to stand by himself and enjoy moving on his own four (two?) feet. Identity doesn't have to be set by one's form but it is dictated by one's name and one's actions.

Oh! And also one doesn't need to secure one's self alone. Throughout the film, Chihiro is always relying and being helped by people in order to get along in life. I do think that this film is part of Chihiro's coming-of-age journey but she does not become self-sufficient or independent and confident through her own efforts alone. She is grateful to Kohaku for all her help. It is he who tells her to remember her own name and he also remembers it for her too. And it is Chihiro, helping him in many ways in return, who remembers his name for him.

There is also an environmental message in the film. The most obvious example is Kohaku losing his name because his river was forced underground by humans. There is also a shot of the bathhouse too. From a side shot, we see that the front of the bathhouse is colorful, luxurious and bright. However, the back of it is dark and full of crude machinery. This should be just the same side that Chihiro had to make multiple dangerous trips through to get her job, go see Kohaku, and also return the seal to Zaniba. In other words, people try so hard to make things look pretty and structured but are just hiding ugliness behind it. Comparing Yubaba's beautiful, ostentatious palace to Zaniba's peaceful country home reveals how much more greedy and materialistic Yubaba is. Although… I mean Yubaba's hut is actually pretty luxurious going by country standards? Lots of space, cabinets, beautiful furniture… but it's a bit unfair to judge because how "frugal" or "minimalistic" should one be in order to not look greedy, huh?

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spirited Away

Having been so long since I last saw this movie, I had not only forgotten a good amount of the story, but I also had not appreciated it as much as I do now when I first saw it. I remember much about the fantastical world that this film brings to life, like Haku the dragon, No-Face, the train that treks along the surface of the water, but it’s nice to now understand at least some of the intent behind the creation of this world.

Obviously, capitalism and industrialized society is a big theme in this film. It has become so prevalent that it seems to even have permeated the spiritual realm. There is a nice shot of the bath house when Chihiro first sees it while her parents scarf down food, with a beautiful, bright green tree on the right of the building, and a tall, dark gray smokestack on the left. This shot exemplifies the nature of not only this spiritual world, but the real world as well. Haku, the spirit of the Kohaku river, is being controlled by a black slug to serve Yubaba’s capitalist endeavors. The other river spirit that we see comes in extremely polluted by modern industrial society. Bikes, fishing lines, metal debris, etc. can all be seen coming out of him when Chihiro is helping him. The people in the bathhouse assume him to be some sort of stink spirit and ignore that his existence as this sludge monster is a direct consequence of their own lifestyle. No one would have helped him like Chihiro did, and in fact they try to turn him away at the door, purposefully trying to ignore the problem that they created. This is especially ironic given that it is a bathhouse, a place where people are meant to become clean and refresh themselves, but the bathhouse itself is run by Kamaji, Lin, and the soot sprites, beings all enslaved to the system to work in horrible conditions with little to no hope of escape. This is also a nice commentary on the nature of working conditions in a hyper-industrialized society and how those at the bottom work endlessly in cruel conditions, e.g. having to walk right up to the fire to throw a piece of coal in, so that those at the top, Yubaba, can live in luxury.

Another important aspect of this critique is the transformative nature of the bathhouse, or capitalist society. Because the name of the game is money and wealth at the expensive of nature and of others, those inside the bathhouse are changed for the worst in this pursuit. Most obviously, No-Face, who changes from a silent, distant figure, to an insatiable monster who literally consumes other people, much like the exploitation of others in pursuit of personal wealth in a capitalist society, and also continues to attempt to satiate his hunger with more and more gold. In the end however, he truly wants Sen, and when he cannot buy her with gold, tries to consume her instead. Sen/Chihiro in this film has the power to exorcise this “demon” of capitalism, first healing the river spirit, and then using the ball given to her by the spirit to force No-Face and Haku to throw up the things causing them to feed into the system.

In this film, there is no one “bad guy”. While it is true that Yubaba would be considered thus, there is a reason that she has a twin sister. Chihiro referring to both of them as Granny shows that she knows that they are truly two sides of the same person – Yubaba being the embodiment of capitalist greed, not realizing that her own child has been replaced, and Zeniba as the kindhearted, mother figure that truly cares for her children. In reality, good people can become corrupted by this system and become completely different people, like we see with Yubaba and also No-Face, who at the end of the film reveals his skill with sewing and his timid, kindhearted nature. Even Haku, who Lin is extremely opposed to fundamentally, carried out the “dirty work” of Yubaba as a result of being plagued by Yubaba’s system and in reality, was a kind river spirit that saved Chihiro as a young girl. No one character is bad, and every character has a complex relationship with life, existing in between the worlds of the industrial and the natural.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I like how you mentioned the different ways that the two clan leaders show disregard for their men. They are definitely both selfish in their motives but in vastly different ways and you picked up on that very well. Nice analysis!

Sukiyaki Western Django

A really strange movie! Not only was the first set and scene we saw representative of how strange the entire movie is but also the themes and struggle of the movie as well. English voiceacting, Western cowboys within Japanese aesthetics (Quentin Tarantino, the cowboy clothes, the red sun and Mt. Fuji), the Genji and Heike war as well as the War of Roses in England are all gathered together in one location. It's an unusual mix of older time periods from America, England, and Japan. What's most unusual is that these aesthetics aren't clashing at all but are all being made fun of in some way and made equal in a way.

In the first scene, Quentin Tarantino directly compares the Heike and Genji war to the War of Roses. After reading Shakespeare and learning about the War of Roses (in which the red side won), Kiyomori changes his name to Henry to suit his desires. There is very little sense that the Japanese or Western aesthetics are meant to be at odds or totally separated. The head of the Genji even makes fun of the samurai way of life, seeing it as only for appearance's sake. This same head still brings a sword to a gun fight despite having shown great prowess at the gun earlier in the movie (when he's shooting Kiyomori). Rather it seems both Japanese and Western aesthetics are useful and tremendously cool. Our loner (and most of the Japanese characters) wield Western aesthetics and Quentin Taratino is an "anime otaku at heart".

The color palette of the movie also makes both red and white seriously stand out. All the blood in the movie almost sparkles especially when they're spitting it out of their mouths. The snow as the loner and Genji head are fighting at the end is also amazingly crystal-like too.

Returning to Kiyomori a little, it's interesting how his ilk are quickly outnumbered by the Genji over the film but not because the Genji are amazing at being murderers (well part of it is). It's that Kiyomori is using his own men as meat shields to save himself. At the end of the film, he keeps repeating "this time we'll win" but switches to "I'll win" just before he dies. He never cared about the Heike. He only cared about his own survival and his own victory. The Genji are incredibly similar too. In multiple scenes, the head shows he does not actually care about his men. When he is "teaching" a man to block a sword, he doesn't care if the man dies or not. He only cares about his fighting style, his ideal. If someone can't meet that ideal, they're not worthy of this fighting style and all they did was fall upon their "life of fighting". In other words, the Heike and the Genji are very much the same. Obviously, there is no good guy because good guys wouldn't rob a child of his parents.

In that sense, I find it hard to think that even the good guys of the film are really "good". I mean they're definitely NOT okay. It is absolutely true that from the moment Akira dies, that is the end of Heihachi's happy family. His mother turns to the Genji and hands herself over for the sake of killing Kiyomori someday. It's probable that Ruriko became Bloody Benten for the sake of vengeance as well, turning away her music. She even stops her peaceful life in order to die for vengeance too (for Akira's death). Of course the loner appears to be traveling through towns, getting himself involved in Heike and Genji fights just to sate his own thirst. Vengeance touches the hearts of every "good guy" we know and it robs them of any drive to be a true parental figure to Heihachi. That is why everyone leaves him behind at the end of the film whether they're dead or alive. Yes, war in its vaguest, most sinister form did infect them but it was also these characters' choice to go and die for the sake of their vengeance. Heihachi, whispering "love" to himself, might manage to turn out different from the adults in his life. After all, it's a little unusual when you compare the scene of the loner crying as a child just to shout in rage versus Heihachi crying while whispering "love".

But hell, I don't know what the meaning of "Django" is so who knows?

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sukiyaki Western Django

Sukiyaki Western Django is more or less what the title suggests, a mix between Japanese, American, and Italian cinema, making reference to the term “spaghetti western”, with a Japanese dish instead. The setting itself immediately portrays that effect, with the traditional western town in a more Japanese style, with a town gate and Japanese-style buildings. The opposing factions, very Shakespearean in nature, as the film blatantly draws our attention to, are both samurai and cowboy, with the costumes an eclectic mix of cowboy hats and katanas. I felt that all of the symbolism this movie used was forced into the viewers attention and explicitly explained, with the love between Shizuka and Akira being forbidden because of the war between factions, and Heihachi as the symbol of that mix, as well as the roses. The imposition of Japanese actors speaking English as well as the Shakespearean story on the general historical time period of the California gold rush is a very interesting one, as it both grounds the story in time, but also throws all chronology out of the window with how asynchronous all the moving parts are. I believe that this strange mix of so many different influences is meant to show just how diverse western films are. Popularized in Italy, based in America, and no shortage seen in various other parts of the world, the western genre exists in modern cinema much like how it is portrayed in this film.

While I appreciate the intent for all of the Japanese actors to speak English like in a traditional western, and that the fact they themselves do not speak the language ties into the point I just made, it was very hard to ignore. Because the actors don’t all speak the language, so much of the delivery in this film fell flat for me. The only moment in the film that I felt was expertly delivered and really filled me with the intended emotion was the scene when Shizuka witnesses Akira’s death. The actress really shines here, as her pained screams while Akira is comically unloaded into by Kiyomori, was a nice emotional break from the over-the-top, ridiculous action of the film. That was another aspect of the film that made it a very enjoyable, almost comical watch. I felt that a lot of the reason for this film, aside from the point about westerns I made, is for spectacle, and it sure delivers on that front. The ridiculous 2000’s era editing, combined with the impossible, yet hilarious, action stunts during fight sequences, to the grotesque gore in some scenes all combines for a visual treat that I haven’t seen in many movies. The perspective, however, of this kind of theme of the time period of the gold rush, as a Shakespearean bloodbath for reasons that become lost over time and transform into solely a war between factions, is an interesting one.

Overall, I’m not quite sure what to make of this movie, other than that it serves as what I assume is a bit of a love letter to western films, specifically in their diversity in the world of cinema. I also was not at all expecting Tarantino to show up, which was quite the surprise.

1 note

·

View note

Text

I love the point you made about nature being a connecting force for us. I think that the scene at the end with all of the people under the trees together is meant to contrast the society we saw previously in the city, where rumors spread and people judge others. There is this dichotomy between what people use to connect with one other, like food also, and what things society uses to exclude and divide. Great analysis!

Sweet Bean

I clap my hands. Wonderful, amazing! It's so funny to watch this after Pulse's tirade (the word lovingly used by me) about the epidemic of loneliness.

The found family aspect was wonderful to see emerge between Tokue as the mother, Sentaro as the son, and Wakana as t

he granddaughter. It is such a gradual realization confirmed finally in Tokue's last message to the two of them that was so sweet to hear. I think what creates this strong feeling of becoming family are the scenes of Tokue and Sentaro working together to create dorayaki especially when compared with each of them struggling to create dorayaki on their own and also the conversations Wakana has with each of them. To begin with, Sentaro giving Wakana the rejects is already a sweet gesture that implies they have a strong relationship. Furthermore, Wakana somewhat sharing a meal with Sentaro (especially when it's clear her mother has abandoned her to go find dinner on her own) and giving him advice about Tokue's employment feels a little like a consultation between family members. Of course Tokue giving Wakana advice about how to live her life freely and offering to take care of the canary was very sweet and grandmotherly.

On another note, the use of sound was kind of interesting? I mostly noticed it whenever Sentaro was walking up and down stairs. The heavy thuds of his depressed steps when we are first introduced to him as well as a similar after the dorayaki shop starts to crumble are so loud that it's unreal and emphasizes the sense that something is going wrong for him. Otherwise, the contrast between Sentaro carefully crafting his pancakes while the middle school girls noisily chatter in the background was seriously hilarious. The film is able to use sound in ways that set the emotional tone of scenes in interesting ways.

To end, the relationship between Tokue and nature is interesting especially when considering that quote from the book about leprosy. Those with leprosy/Hansen's Disease want to live in society "where the sun shines" too. Tokue listens carefully to nature and this way she is alone and lonely but surrounded by beautiful and noisy nature. The film shows us and lets us hear the sounds of the nature that Tokue loves so much throughout the film as well. It feels like nature is also society, that both are one and the same, and by enjoying nature we can also become part of society as well. The ending scene of all the people cherry blossom viewing and Sentaro setting up his own stall, calling out to them, might be representative of this as well. Everyone loves nature! We're all looking at the same moon!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sweet Bean

Sweet Bean was a very heartfelt movie, albeit not a very surprising one. Despite the plot being fairly expected, it was still a wonderful watch. Of course we have the metaphor of the caged bird that refers to Tokue. Forced to live in this “nursing home” for those who suffered from leprosy, Tokue was denied a normal life for the entirety of her life. When she finally comes out of her cage, however, she lives life to the fullest. She instantly looks to find purpose in the cooking she has come to love so much, and even finds a relationship with Sentaro that she couldn’t have with her own child that she was not permitted to have. She socializes with the youth, the younger girls at the shop, encouraging them to enjoy their freedom and their life at school, as it was something she was never allowed to opportunity to do. A beautiful, caring soul that was robbed of the beauties of life by society, Tokue’s warm and smile-inducing character makes her death that much more impactful.

Of course there is also the theme of the unjust, forced quarantine of leprosy patients, even after scientific advances of treatments and cures, as well as knowledge that it was not as contagious as the more antiquated anxieties feared it was. The consequences of this harsh government action are the reason for Tokue’s sorrow and go to show the lasting effects of not only the policy, but also the societal prejudices against those affected by the disease even after the policy’s eradication. The mere notion that Tokue had leprosy was enough to completely reverse the success the dorayaki shop, despite any confirmation of this fact and the fact that she was not contagious at all. Societal fears and prejudices are very strong, and this film strives to depict the life-robbing consequences of those fears and the sadness it causes.

Sentaro also spent a good amount of his life in a cage, but for very different reasons. The fact that he hurt someone so badly to the point of disability means that at the end of the film he understands how he has permanently affected that person’s life and the things that they may not have ever been able to do or enjoy because of him. Because he also loses his mother while in prison serves to foster that mother-son connection that he establishes with Tokue in the film.

I love how the movie depicted the passage of time, using super vibrant colors and beautiful shots of nature in Japan to show the changing of the seasons. Tokue, her symbol of the cherry blossom being established, passes away in the fall, perhaps early winter, when the cherry blossom is out of bloom, and the life that she lived in the summer and prior has passed. But it is at the end of the film that we see Sentaro, tiny dorayaki shop all set up, in spring, beneath a cherry blossom in full bloom overhead. Tokue as the cherry blossom is watching over him as he begins to make dorayaki for himself, and a new year has begun. Sweet Bean was a beautiful film about what it means to live, death, and good food that addresses a very serious issue in Japanese history, that is but a part of a larger issue of the images society gives to certain people.

0 notes

Text

I like what you said about how the loneliness is something that the spread of technology takes and worsens. In my initial viewing I saw loneliness as something caused by the spread of technology, but your view is more nuanced. Instead, technology and the internet as this new popular promise of a solution to loneliness has simply made existing loneliness worse, and that is the reason for all of the deaths. Great analysis!

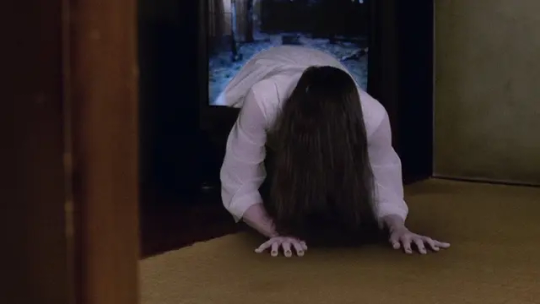

Pulse

I don't watch a lot of horror movies and most of the ones I do are tied to some awful evil or crime made incarnate as a monster. Sadako, Chuckie, and Jason are all examples of horror I'm used to. Therefore, the existential horror, the epidemic of loneliness, presented in Pulse was incredibly thought-provoking and closer to home in a way that makes it more terrifying. I admit I don't think I was touched by this movie as other people would be because of some unique experiences. Despite that, I genuinely appreciate how the film sensitively depicted the crushing despair and resignation that loneliness causes. Loneliness is both the creeping sense of total despair and fear of an inevitable future (whether it's true or not) and the depressing resignation - as if the world has just ended - as you decide it's totally hopeless. When I'm thinking about this film, I adore it.

Initially, I thought the screens depicting people wandering around their rooms or killing themselves were "ghosts" of people or memories they left behind that continue to haunt the living. This includes both the people who care about them and the strangers stumbling upon these relics of dead people. It's like seeing old forum posts from years and years ago and wondering where those people might be or if they're even alive. To see these screens, along with the "help me" plea, seemed just like cries for help and I don't think I'm entirely wrong. Everyone in the film, the best example being Harue who seems to have scrawled "help me" over the walls of her bedroom, want to be helped from their loneliness. They always fail to feel connected to someone no matter how much time they spend with someone else in person.

This failure to connect with people is obviously tied to technology in some way. In the beginning, Taguchi seems locked to his room. The mood change is instant when we move from what is a cloudy day outside, full of people and plants, to his room that seems like it's always night in there. The curtains are drawn, the lamps are on, and there's a coffee cup on the table that implies he's been living all-nighters every day and every night. Initially, I thought the film might have shown its hand too early: People seek the internet in order to connect with people because they can't reach people in the real world. It turns out that these connections are just as fake and in despair we flee the world of the living. Therefore, the true answer is that we have to grit our teeth and stay connected to the real world, you know? After all, you can't ever reach anyone by phone either and even if they answer, they can only ask for help without trying hard to receive it or they just shrug you off. Just like real life. Do you remember the boss of the flower shop saying something similar? Friends say wonderful things during the good times, with the best of intentions, and it only hurts the people they're trying to reach. That is, the message seemed exceedingly pessimistic not only about one's own effort to stay connected but also about technology. I'm… still not THAT wrong in the end.

That's why I feel conflicted about the possible reason for the disappearances was "ah, you see… the other realm is just overflowing with ghosts. It can't be helped, you know?" Not only does it sound like a conspiracy theory but it's one that turns out true as people disappear the world over. An actual apocalypse caused by ghosts! However, it does seem to tie in neatly with the idea that through technology, people (or in this case ghosts) take advantage of other people's loneliness. It's a common story. Catfishing is just one example.

About the real world crisis, the segment in which a TV is naming all the people who have disappeared hit me the most. Not only young or middle-aged people but the elderly and kids are named too. No matter the age or reason or past, loneliness can affect anyone. Loneliness is an epidemic. Of course I don't disagree. Just saying "we all die alone" is a terrifying statement generally and there are people who dream of dying surrounded by loving family. Not just loneliness but death too is a topic people feel strongly about.

That seems to be the core of Kawashima's narrative. Throughout the film, he refused to confront death to the point that he blabbered on about being able to live forever once people make a miracle drug to Harue. He doesn't want to think about death he says repeatedly. Then he is forced to confront death in that forbidden room, made to hear Death speak to him, and to touch it physically. That is, death comes for us all and we have no choice but to confront it. If we are lonely in life, we are lonely in death, Kawashima only got so far because he never seriously considered death and always ran away from it. I have to be honest. I think everyone in this film is a bit cowardly. No one confronted death properly but instead focused on their despair and fear. Depression is a serious issue and whether you're depressed or not it takes serious dedication to remain optimistic and dedicated to enjoying your life. It shouldn't matter if you're alone or not, if you're lonely or not, because life isn't just people. However, I admit that there is no one-size-fits-all, "proper" way to confront such an amorphous, unknowable thing. Anyone might say the world over just hit its limit and couldn't take the loneliness anymore.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pulse

There are a lot of similarities between Ringu and Pulse in the way that they display anxieties. However, I feel that the eventual product of the spread of technology that Ringu alludes to is the apocalypse that is realized in Pulse. However, whereas the video tape and technology in Ringu was a way for the rage of Sadako, a figure of the past, to take on real effect in the present day, Pulse is very much more focused on the collision between worlds.

This is on display early when we see the computer program that eventually leads to Kawashima’s encounters with the world of the ghosts on his PC: UR@NUS. Using the name of another planet with the ‘@’ symbol is a clear reference to how the world of technology and the internet are becoming this means for the alternate world of ghosts to come into contact with our world. The symbol of the door with red tape around it, The Forbidden Room, also as portals to the other world is strong as well. The horror of the fact that ghosts are coming to our world and spreading by means of technology is amplified by the sheer omnipresence of technology in society, which is portrayed in the film well. Computers are everywhere, and Kawashima only decides to try out the internet because everyone else seems to be doing it. He has no real interest or knowledge in technology, but because of how massive and common it’s becoming, someone like him, who might have never taken interest in it before, is now at risk because of it. We see mobile phones that everyone carries around with them, TVs in every house, huge PC labs at universities, and even Kawashima’s PC is right next to his bed – the most vulnerable and personal spot in a home. There is no escape from the ghosts when they begin to spread through modern technology because it dominates every aspect of human life. Computers are even being used at Michi’s plant shop, which operates on the roof of an urban building. The “natural” world is disappearing and becoming tainted by modern technology, as we see with the plant shop.

There is also an overwhelming sense of powerlessness in this movie. Nothing that the characters try to do something about the situation or save people ends up working. In fact, due to this omnipresence of technology in society, once the ghosts began to use it as their means of coming into our world, it was already too late, and there was no way to prevent the apocalypse that ensued. Michi tries to check on Taguchi, who hangs himself when she steps away for a moment. She tries to help Yabe, to no avail, as well as Junko. Even in the end, when it seems that she and Kawashima might be able to survive this apocalypse together, even he falls victim to the ghosts. Kawashima is also unable to save Harue, despite how close they came from escaping society. In the end, Michi is able to survive by escaping society and land as a whole, isolated on a ship at sea. At one point, Junko says to Michi, “let’s just act normal”, or something similar. The overwhelming truth of being too powerless to do anything makes willful ignorance an alluring choice, and perhaps refers to people’s willful ignorance at the dangers and threats of the spread of modern technology.

The other interesting theme in this movie is isolation. This is also a theme in Ringu, but I think it is done very differently here. After a person comes into contact with a ghost and becomes condemned to death, they are distant from others socially, verbally, emotionally, etc. We see this with Taguchi at the start, who is very reserved in his interaction with Michi. We also see it in Yabe, when Michi is desperately trying to figure out what is wrong with him. He basically ignores her and Junko when he first arrives late to work. We also see it with Junko, and she displays far more of this feeling of isolation with Michi. When she is with Michi she stares off in a trance, seemingly not aware of her presence, but when Michi walks away, she becomes distraught, reaching out to her. Even around others she is isolated. Michi also says “I’ll just keep on living, all alone” moments before her death too. Despite the ways that the internet and technology connect so many people together on a daily basis, Pulse seems to suggest that its spread will simply create more loneliness and social isolation. The result of that loneliness in the film is always death or suicide, leading to a society where there are simply no more people to connect with because they have all fallen victim to technology and its subsequent loneliness.

0 notes

Text

I like what you mentioned about a potential feminist reading of the film. I hadn't thought of that when watching it but I totally agree that there could be something there. Having not seen this movie before or any of the sequels or remakes I find your comment about them leaving out the "Japanese soul and mythology" interesting, and I'd love to know more about the actual myths behind the film and what inspirations it takes. I'm looking forward to discussing it in class and learning more!

Finally J-Horror!!!!!!!!1111!1!!!!111!!!!!!!!!

I've seen this movie like a million bajillion times in my life, including all the remakes and the sequels, etc. so I am coming from a biased perspective for sure. However, this is the first time I'll try to actually analyze what I'm watching instead of just enjoying it.

The director utilizes a slow progression to really stress you out. So much of this film is faking you out for whats going to happen--the jump scares aren't utilized as actual jump scares of terror, but more mundane things with a sudden cut or noise. It does well showing a lot of the tragedy of the deaths off-screen or with those filter freeze frames. It can be a little goofy, but also its 90s horror and I eat that shit up. Even the ending, or what you think is the ending, is a fake out making you think that love and compassion and acceptance is what's going to lift this supposed curse when in reality, nope! It's actually perpetuating the cycle and pushing off the curse onto someone else to save your own skin.

I think it lends a lot into what Sadako's character is--a traumatized, abused little girl that has a scary ability and was ultimately killed simply for her existence. So many people were complicit in both the death of her and her mother, as well as the stress they had to deal with in life. Her anger is what fuels this curse and gives her the ability to utilize the 90s technology to punish, well, everyone.

The use of technology for this particular brand of horror is interesting, too, because in the 90s (esp 98 and the years leading up to Y2K [did Japan have a freak out about that too??]) a lot of people were stressed and scared of the rapid expansion of technology. You could argue that this film takes that stance or at least highlights what people were afraid of during this time, that television, movies and even phones can bring horror literally into your house if you aren't careful which is represented by Sadako infamously crawling out of the tv.

I love, too, that the story can be read from a feminist perspective as well. Both Sadako and Shizuko were mistreated by so many men in both of their lives and ultimately met their fates at the hands of men. It is then, interesting, that within our leads only that the man dies. Has nothing really to do with their actual intention, because Reiko was going to die regardless unless she copied the movie, but I digress. I can see how this analysis can be argued.

The American remakes definitely utilize more jump scares and out-right horror elements, but nothing beats the original feeling of dread and the fact that the fate can't entirely be escaped. The remakes also remove the Japanese soul and mythology tied to it and I think that's shitty.

I have more I could say, but I will cut this here for now. My girl Sadako never did anything wrong in her life.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ringu

I have actually never seen Ringu or any of the sequels/remakes before, so going into this movie, I was very excited to see what it was all about. From my limited pop-culture knowledge of this film, all I knew was that if you watched the tape, you got a phone call and died in a week, and then the girl comes out of your TV to kill you. Luckily there is so much more to this movie than what I knew, so it was a super fun watch and new and fresh experience for me.

One thing I love about horror movies like this is how they play with tension. So so many horror movies will only use tension to eventually just jump scare the viewer and then all of the tension is immediately dispersed in that moment and that’s just what the experience is. However, in Ringu, tension is all that is built. There are no real jumpscares here, but every moment has so much suspense and tension, and that’s what seems to be the true horror effect in this film. I think the best part about this tension that makes it work so well is just how little information we are given throughout the movie. Even at the end of the film there are still unanswered questions like, “What really is Sadako?”, “What is up with Shizuko and also Ryuji’s(?) powers?”, etc. But the denial of information throughout the film really amplifies the sense of dread and horror that both the characters and the viewers feel.

There is a very prominent theme of isolation in this movie. Both Sadako and Yoichi are somewhat isolated in this movie, which explains why Yoichi feels such a “connection” to her and eventually ends up watching the tape. Reiko is always working, and Yoichi is used to being on his own. When he sees his father in the street, they don’t even exchange a word before walking away. Despite Reiko’s love for him, which is undeniable, we never really see Yoichi reciprocate. He doesn’t ever really smile or laugh, except at his grandfather’s, who he later says is boring. Also for Sadako, she is treated by everyone as a monster and an abomination and is killed for simply existing thusly. I think the fact that we never see her face behind her hair is very significant, because it shows that she is cut off from everyone else and is incapable of truly being known or having any kind of connection. In fact, the only time we see her face is when Ryuji is killed, implying that actually seeing her face and coming to know the truth of who and what she is, is fatal.

I also really liked the twist ending, making the audience think that the solution to Sadako’s curse and anger was love and acknowledgement, an end to her isolation, when in reality, the cycle is never-ending, and one must simply pass it on to another in order to save themselves. In truth, Reiko only went to find Sadako’s corpse and gave her “love and affection” to save herself and her son’s, the true object of her love and affection, life. If not for Sadako’s murders and threat of impending death, no one would’ve cared to solve her death or bring her any kind of peace or justice. I actually did not know that this theme of not being able to escape the cycle of the curse and simply needing to pass it on to another unfortunate soul to save your own life came from Ringu. So it was very funny to recognize that horror movies from my generation like It Follows, are simply worse takes on that same premise. But it was also nice to recognize the lasting influence that this film has had.

I think the use of technology in this film is also very interesting. I think that this movie was very ahead of its time, as the reason that technology, specifically TV and VHS is so scary in this movie is the way that it spreads. If this footage is dissipated enough, it can reasonably be inferred that eventually everyone will have seen the tape and there will be no one left to pass the curse along to in order to save yourself. This idea of technology spreading horror and bringing it into one’s home, like when Sadako literally crawls out of the television, it something I think is far more prevalent and relevant today, with the internet. So it was very cool to see such an idea happening as early along as the 90’s with television and VHS tapes.

1 note

·

View note

Text

I like what you mentioned about whether Ageha's memory was the girls or the butterfly's. From the perspective of the butterfly, it is trying to escape the bathroom that's trapped in, and almost makes it before it is crushed in the window. Maybe then this shows that Ageha might not ever be able to truly leave Yentown. But at the end of the film, it seems like that's where she wants to be, with the people she loves around her.

Swallowtail Butterfly

When I try to write about this film, there is so much I think about that I can't start at all. I think that I will talk about names. There are real names and then there are street names. There are names you are given from birth or names you give yourself or names given by other people. I don't know if names are a major theme of the story - something everyone thinks about given all the tragic and comic events we are given - but I am really attached to the idea of names.

Ageha and Glico have such a wonderful familial relationship. Like Rinki gave Glico her name, Glico gave Ageha her name. Glico is a candy that Japanese businessmen grow up sucking on, sucked on til it's all gone. Ageha is the name of the swallowtail butterfly that got squashed. In other words, like Rinki is Glico's older brother, Glico is Ageha's older sister. Therefore, through that familial connection, Rinki is also Ageha's older brother. Do you remember that scene when Rinki finds out Glico's wonderful career as a singer? He caresses the sick Ageha's hand and it isn't sexual. It kind of seemed like an older brother comforting his sick younger sister. He's reminiscing about his past with Glico and there is Ageha as an intermediary. This is what I think about when I think about how this film uses names. He didn't even know their connection until the end of the film.

Names, right? Why do Glico and Ageha's names have such a destructive aspect to them? I feel like there's some deeper meaning there I don't get.

People's names reveal something about them. Fei-Hong is Chinese (but a follow-up has to be asked! From Shanghai? Yes? No?), Arrow is an ex-fighter, Suzukino and Suda are obviously Japanese, and isn't there something a little bit odd about Rinki for a Japanese name? Glico sounds like a prostitute's name, doesn't it? Even nicknames are revealing! Don't you remember that back-alley doctor joking about calling himself Rock Doc? What a comedic personality! Names are people so who is Ageha when she didn't have a name in the beginning? Ageha's growth in the film probably starts from the moment Glico gave her a name. I think you could go into the aimlessness or confusion of an existence like that. She hardly spoke in the beginning, gets slapped and has to say she doesn't have a name, and scoffed at. After all, doesn't everyone have a name? The scene when Ageha is recalling a scene from the past while getting a tatto presents the question of whose memory it was: the butterfly or the girl's? Wasn't some of the 1st person views from the butterfly's perspective after all? Well, it might as well be both. She is called "Ageha" after all.

Anyways, I really like this movie.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Swallowtail Butterfly

There was a lot happening in Swallowtail Butterfly. I loved the use of language in the film, a creolized mix between Japanese, Chinese, and English. This aspect of the film did a lot to paint the picture of this fictionalized world of Yentown, as a mix and interlacing of cultures, blending identity. The fact that there are so many people of different backgrounds that speak different languages, and the fact that the movie opens with the explanation of Yentown as a more futuristic version of the American gold rush from 1949, makes me think that this is a take on American culture. Perhaps the fact that this idea of culturally ambiguous slums of immigrants coming in search of a better life taking place in Japan is meant to serve as a critique of an increasingly American or western cultural attitude rising in Japan.

One symbolic thing I noticed was the way that funerals are conducted by the Yentowns. At the beginning of the film we see Ageha’s mother’s funeral happening at the police precinct, presumably because they cannot have traditional funerals in their situation. Despite their severe need of money, they burn money on the body. I think this connection with money as the way to live is the reason for this burning. Perhaps it was her mother’s money that they burned, as her life, and therefore her money, has passed. Opening the movie with this and then including the scene towards the end where Ageha burns all of the money that she made by counterfeiting after the death of Feihong, is a nice parallel.

Another interesting aspect of the film that is related to this idea of a cultural mix, is that of how identity is forged in Yentown. Because of the influences from so many different languages and cultures, and the fact that most of our characters have spent their whole lives in Yentown, creates this sense of Yentown as almost its own country. The Japanese see the Yentowns as one kind of people, despite what language they speak or where they come from originally. None of that really matters because they are from Yentown. It is also in Yentown that people like Glico and Ageha find their identity and are even given their names. Glico does not receive her name until she comes to Yentown with her brothers, and Ageha receives hers from Glico. This idea of names shows that some of the characters receive the entirety of their identity from Yentown. Unlike Feihong, Ageha and Glico do not have a name from their place of origin, and therefore have no personal connection with any place other than Yentown. So it is in their attempt to escape from this place through money, wealth, and material gains, that they all end up disillusioned and unhappy. But it is together, really no matter where they are, that they find the most fulfillment in life.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love the details you mentioned of the final scene. The camera panning away while the music swelled was definitely the most lively moment of the movie, just to be abruptly stopped by the ringing out of the two gunshots, the inevitable deaths of Nishi and his wife that they have been rapidly approaching during the whole movie. Those details of how it ends exemplify that central theme super well and I'm glad you brought attention to them!

Hana-bi

I banged my fists on the table at the end of this movie but I don't dislike or like this movie. Mechanically, this is a wonderful film! That final scene almost seems like heaven as Nishi and his wife watch a replacement for their lost child play on the beach on a bright sunny day. The camera pans away as Joe Hisaishi's music plays on serenely as if everything is going to be okay, seriously, really! And it's such a long pan out to a dreamy, blue sea. And then two gun shots ring out.

This film was obviously going to play out horribly from start to finish. I don't know if anyone could seriously take that last scene and think to themselves, "Wow! I hope things end well!" Was there a single doubt in anyone's mind that someone wasn't going to die on that beach or - even more - that Nishi and his wife didn't go on this trip so they could make some memories and die in a double suicide? Seriously? I didn't bang my fists on the table because I was grief-stricken. I banged my fists on the table and laughed because it was finally over in exactly the way I thought it might! Horrifically! Tragically! And what a final scene! Trying to seriously pretend that everything's okay when it seems nothing's been okay for Nishi or his wife for years ever since their child died.

This movie is quick to tell you what the characters have lost and what they will lose. Nishi already has a dead child and a sick wife. Horibe is soon to lose his family, status as a cop, and his legs. Within 20-30 minutes, the pieces are already set: Nishi feels the loss of his family, feels responsible for the death of one cop and the harm to two others, and doesn't have the money to cope with the enormous loan he took from loan sharks. Horibe is going to live the rest of his life, horribly lonely and only having his painting to help him express what he can't tell other people.

Before going to Nishi, it's interesting that Horibe's paintings constantly substitute animal heads and forms for flowers. The explanation behind these paintings seem to come from a couple scenes. In one, he explains that he can only paint what he sees (like remembering the family of three walking on the beach). In another, he is passing by a flower store and is inspired by the flowers he sees. We get painting after painting he will inevitably draw but there is one yellow flower that stumps him. The painting he creates, of an a woman and a young girl dancing in yellow dresses, is the only painting where the figures are turned towards the viewer and they actually have faces. Horibe is expressing his deep loneliness and desire to see his family again through his paintings.

What does Nishi express? When? He is deeply connected to his coworkers and to his wife. He smiles when they tell him good news (one of the cops is going to get married!) and he smiles and laughs with his wife as they play games together and joke around. And he instantly drops back into a face that is lost and seems to be looking at nothing when one of them mentions their dead friend or Horibe. That latter expression is exactly the expression that Nishi wears for most of the film. He is stuck in one flashback, the event that he was able to live through and become obsessed with, and it memorializes what Nishi lacks: self-control.

Nishi attacked the gunman and that led to the death of one friend and the injury of another. At this point, he already lacked control. I would not be surprised if it is implied that Nishi and his wife stopped talking much after their child passed. Both are so reticient except when Nishi has to speak or when the two are peacefully together. In that sense, both were losing their self-control together. This is why she was able to pack all their things and set out on the trip, why Nishi rang the temple bell, why they laughed like kids throughout the trip, and why they probably killed themselves at the end of the movie. Nishi's lack of self-control was easy to see: he smoked in the hospital, he was violent beyond necessity (shooting a dead body, killing yakuza, hitting that dude with glasses at the end of the film), and recklessly borrowing and spending money to send packages to the people he felt he hurt and also to go on a final trip with his wife. Everything Nishi did was in service of settling final debts and making memories before ending his life. The entire movie was just us getting to see the reason why!

When did Nishi express himself? Why? He doesn't! Not really! Not in a way that was keenly visible to his friends, not in a way that screamed 'Gosh, I really want some help'. You know what this film reminded me of? The American cop vigilante who deserts the force and becomes all-consumed by the idea of vengeance and justice, only to turn into the very monster he hunts, and then he gets put down or he puts himself down. We, the audience, simply get to see all the gorey, horrible reasons why and we can choose to condemn him or not, discussing the glorious ideas of justice and how to mete out punishment. Here's the differences in this film: Nishi isn't driven by vengeance but by guilt, shame, and the desire to follow his wife. Nishi didn't want to be saved and he didn't attack from a sense of justice. He killed, maimed, and committed crimes to suit his own needs or because he lost his temper. He was so deeply connected to his friends and it was that connection that ultimately doomed him. What would he even do after his wife died anyways?

Also, haha, fireworks are beautiful but fleeting and the lives of the characters are fleeting too! Ooo, Nishi and his wife have fun with fireworks and sparklers and Horibe paints flowers? Amazing! (I'm being sardonic but I do wonder if there are any other associations I'm missing? I guess Horibe painting flowers was a way of saying connections are fleeting but somehow he's still connected to his wife and daughter despite their being something like flowers)

Edit: I feel like I should probably add that the reason I don't feel much respect or sympathy for Nishi and Horibe (despite the very real emotions and trauma they have been through) is not just because the film tagged their tragedies from the beginning but also because they're cops. A very surface-level reason. Nishi is probably off the hook as I feel like the seed of his trauma comes from the loss of his child and his soon-to-be loss of his wife. These two people seem to be #1 in his life so I understand why he abandoned his friends to join her in the afterlife. Being an officer is simply a plot device to ladle survivor's guilt on top and give him a good reason to be a badass. On the other hand, Horibe accepted the risks of being a police officer and so being paralyzed isn't exactly so disgraceful. Admittedly, Horibe's story wasn't about being paralyzed but about his family leaving him. Being a cop also feels incidental in that way. Still, I was left with a horrible feeling that the movie wanted me to sympathize with cops (but the culture in Japan around cops is probably different, huh?).

I also forgot to say that Nishi made decent friends with that junkyard owner, huh? The parallel between these two (losing their temper) are definitely interesting and the owner encouraging him to commit a crime marks him as the only "friend" Nishi had in his new identity as a retired cop. The only one he really accepted it seems based on the scene where he smiles, REALLY SMILES, at the owner waving at him in the back mirror. No such treatment for his former friends. Again, Nishi had no regrets and no desire to be saved. Good for him! Maybe it was a happy ending after all.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hana-Bi

Kitano Takeshi’s Hana-Bi is a beautiful film. The thing that stuck with me the most throughout this film was the gorgeous soundtrack. Every single moment that the orchestra swells, the flutes chime in, everything is filled to the brim with life. I don’t think I’ve ever been so compelled by a soundtrack upon first listen like I have with this film. Upon further research it was no surprise to learn that the composer was none other than Hisaishi. The opening song evoked similarities to that of The Merri-Go-Round of Life.

Getting into the film, I was impressed with Kitano’s acting and directing. From gorgeous shots of the Japanese landscape, contrasted with close ups of a firefly on a leaf in the snow, to lingering shots on various pieces of artwork, this film is extremely artistic in many aspects. Kitano is able to convey profound emotion without speaking a single line, something that not many actors can accomplish so effectively.

The theme of the inescapability of fate and the powerlessness one feels in the face of it is strong in this film. After Nishi suffers so many indescribable losses and painful events, despite his ability to take out multiple yakuza members like John Wick and easily rob a bank, in the end he cannot bring back his daughter or save his wife from her illness. Death is also very prominent, as Horibe attempts suicide after becoming paralyzed. Nishi also, in a way, attempts suicide, always facing impossible odds and a string of questionable actions that he knows he will not be able to run away from forever. But, in the face of losing everything he loves, he would rather do what he can to have the best life possible with his wife in the time they still have left together. It is in the inescapable face of death that Nishi and his wife live to their fullest.

The combination of violent scenes of death and beautiful scenes of relaxation and life paint a poignant picture on the nature of human existence. We strive for love and happiness in the moments that Nishi shares with his wife, but those scenes are always underscored by the inevitable truth of their loss and fate that they are condemned too, which does not allow the viewer to fully experience that joy. Nishi is the same, however, only really showing lots of emotion in his acts of violence. Throughout the film, he embodies a walking corpse, a man so defeated and scarred by loss that it seems he has no true emotions of reasons for continuing. Kitano’s portrayal of Nishi plays into this fantastically, as his rigid slow movements and void facial expressions capture this state of being expertly.

Horibe’s story is somewhat opposite to that of Nishi, as after his failed suicide attempt, Horibe rediscovers his will to live in painting. His paintings embody the essence of life, nature, human being. His story starts towards death and rises up, while Nishi’s plummets towards death. In this dichotomy Kitano expresses his true feelings about life and death, not as opposites or separate entities, but inevitably intertwined, defining each other. Both characters have intense interactions with both life and death, yet their paths are vastly different.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I really appreciated the stories of discrimination you shared of people experiencing in Japan due to their race or nationality. I have heard in a more general sense that this is an issue for people, but the specific examples you gave where very insightful and contextualize this film very well. I also appreciate that this movie shines light on such a prominent issue in Japanese society, especially now given my deeper understanding of the problem thanks to your information.

Yukisadas Go

Yukisadas film was one of the first in this class that has taken a critical stance on racial and nationality lines. Likely born out of the developing changes over time and the Japanese societal ways of integrating other people into their society. This film follows Sugihara, a Japanese born North Korean and his trouble integrating into the Japanese society. He wrestles with discrimination topped with the teenage troubles of love and rebellion with his family. I highly respect this film’s approach to tackling such a difficult topic and bringing recognition to the residents in Japan that face this issue.

Being non-Japanese in Japan and then a minority on top of that garners some strange interactions with people. In public settings, many foreigners experience a sense of isolation just based on being a foreigner. For example, it is not unusual for a foreigner or minority sitting down in a bus or train with open seats next to them and several people avoiding sitting next to them. In some occasions this could even occur in a packed train or bus. On the other hand, open seats with local Japanese are quickly filled over the ones which are next to a foreigner.

Another unfortunate story I hear from mixed Japanese people is that because of their looks and being mixed, they are not treated as Japanese. Even though they went to Japanese school, can only speak Japanese, and are fully integrated in the culture, they are treated as not Japanese. I have heard of biracial Japanese people being spoken to continually in English regardless of how much Japanese they speak. These same racial and nationality challenges are seen within Go. Sugihara is bullied by those in school because of his North Korean nationality. Going through these difficulties exacerbate his rebelliousness and causes him to resent his nationality. This is seen through many of his narration throughout the film where Sugihara criticizes his father in his narration for his pride in North Korea and eventually for him changing to a South Korean passport to be able to travel.

Yukisada did a great job directing this film. He allowed the story to be told through the actors directly and used this coming-of-age film to highlight grievances that people all throughout the world face when living in foreign countries. This relatable and telling film brings attention to racial and ethnic dilemma and establishes a platform to discuss on. I also enjoyed Yukisada’s use of narration by Sugihara and even the multiple instances of flashbacks throughout the film. Even though there were several instances of these flashbacks, the overall timeline and progression of the film remained easy to follow. Overall Go was a great film, that I will have to recommend to my Japanese friends to invoke some meaningful and hopefully challenging conversations.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

GO

Yukisada Isao’s GO is a very well-done coming of age story that deals with the issue of ethnicity and nationality in Japan at the time. For a 2000’s coming of age story, something that someone my age is more than familiar with, this was a very refreshing take, primarily because of the social critique embedded in the story. Sugihara’s character is similar to that of the main character of The Catcher in the Rye, the book he is reading at the party where he meets Sakurai. Not only a social outcast at his new Japanese school, he is foremost a societal outcast, being a North Korean born and raised in Japan. He doesn’t feel he belongs to either culture or ethnicity, getting into fights with his teachers at Korean schools and deliberately speaking Japanese to them, which is forbidden at the school. I love what Sugihara’s one friend from Korean school says about the Korean equivalents of the Japanese phrases he gets in trouble for saying: “it doesn’t sound right”. Being raised bilingually, especially in this instance biculturally as well, creates a very unique identity for these kids. They learn and can speak Korean, but still feel the need to express themselves in Japanese, the language spoken around them in their environment outside of school. Even the notion of language in this movie shows how in-between these kids are.

In addition to Sugihara’s refusal to fully accept being Korean, he also cannot be fully accepted as Japanese due to the societal rules. He and his friends are treated poorly by police, must carry foreigner identification, and we even see the attitude of otherness and dirtiness of anything other than Japanese in the ideas carried by Sakurai from her father when Sugihara first tells her that he is Korean. In that moment, it is no big deal to him, we also see him begin to outwardly express his embracing of his identity as both. He says it’s kind of cool that he is bilingual, and wants Sakurai to accept his identity as confirmation for his own feelings. Thus when Sakurai displays the prejudiced and bigoted ideas about blood and race that her father taught her, Sugihara is so hurt. The entire movie surrounds his struggle with identity, stretched across the canyon between Korean-ness and Japanese-ness, neither side allowing him to exist on one side of the canyon as he is.

We see this crisis of identity and nationality in Sugihara’s father as well, who, after “becoming” South Korean and forsaking his identity as a North Korean, is cut off from contact with his brother in North Korea. In this plot point we see nationality as it is felt by the characters in this movie, a mode of cultural belonging. To belong and connect with the humans around you, you must fully embrace one nationality and ethnicity, meaning that if people’s sense of identity involves more than one of these, they cannot fully belong. I believe that the fight between Sugihara and his father that follows the scene of them talking in the cab results from Sugihara’s anger at his father’s lamentation. His father chose to forsake his identity as a North Korean, but Sugihara was not given a choice. From birth he has been both Korean and Japanese, and has been forced into this crisis of identity, while his father made the conscious choice to change his identity. This is why I believe he is so mad at his dad’s complaining.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love your observation about the transitions, they really are impressive. One thing I remembered is that after the scene with the businessmen that we are introduced to during the training scene, the following scene of the etiquette class takes place in the same restaurant. Very satisfying and impressive film-making, and a great catch and analysis about it!

Tampopo

I'm seriously sad we couldn't watch this as a group together. The first genuinely wholesome movie in a while comes around and we couldn't share the experience together. It's seriously sad!

Despite the movie being called "Tampopo", the film is actually about the experience of eating, making, and appreciating food from the perspective of many groups and people. The main plot centers around Tampopo working hard to learn and upgrade her ramen shop with the help of male professionals (it seems the ramen shop industry is male-dominated?) who each have their own personal connection to food. There's also the group of businessmen who all don't know anything about fine dining except for the most junior member of them all. Then there's the gangster and his girlfriend who mix their hunger and sexual appetite in a surprisingly happy relationship. There's the old man who can't indulge in food any more but continues anyway despite the risk to his health. Each of the competitors and the ways they handle their shops (good or bad) also take center stage. Of course there's also the beginning scenes of those characters (teacher and student) appreciating ramen in their own way and the truckers making fun of them for it. This is not even mentioning small side characters like the scammer being treated to food by another scammer or the dying wife who was able to make one last meal for her family. From start to beginning, this film is about food.

I have to say though. I don't understand what it's saying about food. If there is a central throughline, I ended up never being able to understand it. I ended up with a collection of small messages within the film's scenes.

After watching the film, the characters that stand out most to me are the gangster and his girlfriend. What I mean by a 'collection of small messages' is that he opens the film out in a comedic, meta way. He directly addresses the audience, saying you like eating snacks while watching films, dont'cha? Well, he does too but he just hates potato chips! He has a whole table set fancifully with fruit, champagne, and chicken. His tastes are high culture and he looks down on low-culture food with disdain and anger. It's obvious he appreciates good food. He orders similar food from room service, he looks for and pays for fresh oysters, and his final words are dreaming about yam sausages made from freshly-hunted boar.

The gangster represents high taste and disdain for low-culture foods. He also represents how sexual appetite can be wound up with food. He indulges in sexual play using food and it's a wholesome act he enjoys with his girlfriend. His last words are also about enjoying those yam sausages with her. Their relationship isn't worsened by this greed for food but instead a greed shared between the two of them. His enjoyment of food is similar to his enjoyment of her. Of course, there is something to be said about whether or not he was sincerely seeing his partner or if he only saw her as something to be devoured. The sex scene is something that confused me in terms of the throughline of the gangster's story (it IS the gangster's story, not THEIR story) for that reason. We don't get to know much about his partner after all! Does she even feel the same or is she just food to be looked at and appreciated then eaten by the audience as well?

I like the use of lighting and angles in one of the final scenes. Just to name some examples, there is the way Tanpopo wanders left and right as she anxiously appears at each man's face (recalling the advice to look right at the customer and gauge reaction), how the lighting in the back turns brighter and dark like it's reflecting her up-and-down worry, how the angle changes to reflect all of the men's faces in a pleasing row and the light is almost blinding in how delighted they are with the final version of her ramen. The director's use of angles, pans, and zooms in order to create continuity and focus on character expressions or dialogue is pleasing to the eye in a way. It's a little different from Ozu's style. Both suck you in but Ozu's directing felt stuck in place and almost claustrophobic. Itami's style is far more freeing.

The way the director likes to transition perspective to new characters is also interesting! The best example is during Tanpopo's training arc. Goro is shouting at her to go on running and in the background we see a group of businessmen appear. They go on walking through the background and as they seem to walk off screen the camera follows them! We then transition into seeing their business dinner. A similar kind of transition happens between a man eating, making eye contact with a scammer, and then the scene is all about him. Again, after the scammer is arrested, from the background appears the man who is running to go see his dying wife. These transitions are smooth introducing new characters of interest, giving us time to recognize they exist and wonder what they're doing or who they are, and then moving onto the next scene where they are the stars.

1 note

·

View note