Nepravidelný blog o poněkud dlouhodobějším pobytu v Jižní Koreji, a tak dále, bla bla. Informace ohledn�� studia v Koreji a podrobné info o tomto blogu v části "About me"

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

Gangnam....강남. Famous because if Psy....but completely boring, unless you have lots of money for over-priced shopping or food. There's nothing else to do there anyway.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

(Interrupting the travel diaries) "I may not look as delicious, but I am the first sweet red bean paste Veronika tried to make." "반갑습니다. 나는 베로니카가 처음 콩으로 만들어 봤던 팥입니다. 모양은 그냥 팥인데 별로지만 맛있습니다." #팥 #안코 #요리 #먹스타그램 #비건 #sweetredbean #anko #adzuki #vegan #asiasweet

0 notes

Photo

Only in korean subway...저도 한복 입고 학교 다니고 싶어요....근데 화장실 갈때 힘들겠다...brightens one's day to see it 🇰🇷 #한복 #진철 #한국 #한국전통 #전통 #서울 #특징 #seoul #koreanclothes #koreadress #hanbok #koreastudy #koreatrip #southkorea #subway

#koreanclothes#koreatrip#한복#전통#특징#hanbok#서울#koreastudy#진철#southkorea#한국#한국전통#koreadress#subway#seoul

1 note

·

View note

Photo

남대문시장에서 옥수수술빵~! 이번에는 사진만 찍고 대신 옥수수와 떡 만 먹었음. Umm....I guess it's kind of a "Corn bread". The taste is different from every place they sell it at, I personally love when they add chestnuts, raisins and pumpkin to the mix as well. Another super delicious traditional korean food and so cheap~! #옥수수술빵 #남대문시장 #빵 #옥수수 #전통한음식 #한식 #먹스타그램 #한국여행 #외국인 #비건 #koreanfood #koreanmarket #namgdemunmarket #namdemun #traditionalfood #vegan #koreavegan #vegansweet #veganbread #koreatrip #food

#koreanmarket#food#koreanfood#전통한음식#남대문시장#vegansweet#한식#koreatrip#vegan#먹스타그램#traditionalfood#빵#옥수수술빵#veganbread#한국여행#외국인#비건#koreavegan#namgdemunmarket#옥수수#namdemun

1 note

·

View note

Photo

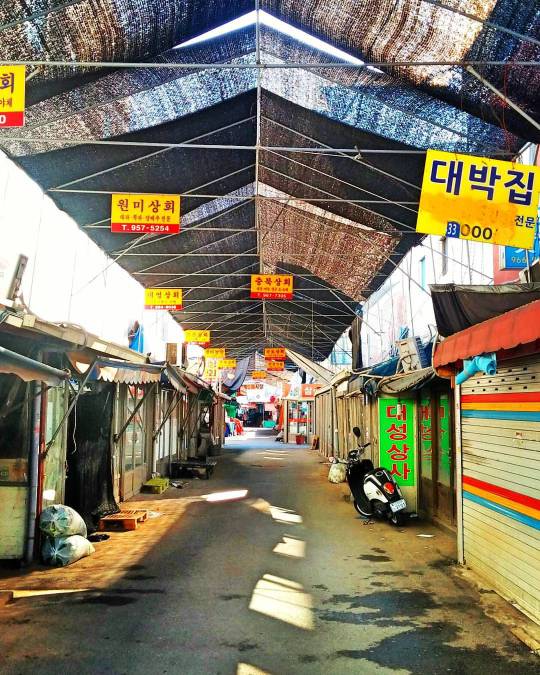

09.13/9:02, the korean traditional Gyeongdong market, still in its morning preparation hours. 오늘 9시쯤. 경동시장. 이거리는 아닌데 옆거리에서는 이미 판매중이였어요. 역시 시장이라 아침일찍일어나서 예쁜 야채다 잡아야 되요! #koreanhistory #korea #koreatraditional #koreamarket #koreafoodmarket #koreafood #farmersmarket #vegetable #traditional #koreastudy #koreatrip #travelling #한국 #경동시장 #경동 #안암동 #한국전통 #한국역사

#koreanhistory#koreatrip#korea#경동시장#경동#koreafood#traditional#koreafoodmarket#한국#koreamarket#vegetable#koreatraditional#travelling#koreastudy#한국전통#한국역사#안암동#farmersmarket

0 notes

Photo

This is exactly how I see Seoul.

NOBUYOSHI ARAKI

ARAKIMENTARI / 2004 / TRAVIS KLOSE

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Korea Herald: Japanese media’s Korea-bashing

A situation I encountered recently on Japanese television was quite baffling. I was flipping through channels when a familiar logo caught my eye: Samsung’s blue oval. I was curious, so I decided to watch TV Tokyo.

And was I in for a big surprise. I had stumbled upon a five-part documentary about how utterly backward Korea was, in particular, Korean firms and the economy. The broadcaster had managed to get their hands on tapes of Samsung shareholder meetings. The part I caught was about Samsung’s sale of Samsung Techwin to Hanwha Group. Unhappy Samsung employees were seen accusing the firm of lacking corporate scruples. In between their testimonials were shots of demonstrations against Samsung in front of the company headquarters in Seoul.

In short, anything damaging about Samsung was included. And the program had secured several “experts” to talk about just how corrupt the company was, and how it lacked any kind of support and compassion for its employees.

Another segment was on Korea’s slumping economy. And here I learned about some very strange new things that were happening in my own country. According to TV Tokyo, almost 30 percent of South Koreans were changing their names in order to turn their businesses around. Amazing. Anyone who actually did this, please email me. Other market watchers talked about how young South Koreans can’t get a job. During the past year I’ve been in Tokyo, I’ve noticed that the media loves it when Korea’s reputation is compromised. TV Tokyo may be unfamiliar to some, but it’s owned by the Nihon Keizai Shimbun, the world’s largest financial newspaper, according to many accounts. I was bewildered why such a major media company would allow its affiliate to air such material. And why the Japanese media actually feels the need to bash a country that’s not up to its level. In my view, such actions only serve to instill bad feelings among both Japanese and Korean people. Last week, I met an official of the Japanese government. He expressed regret that at times, the Korean journalists residing in Japan would frequently take heed of only the opinions raised by the Korean Embassy. I agreed with him. And I understood the situation since I too have witnessed how the foreign press is treated in Korea. With courtesy, but never offered any real access. But in the end, it all boils down to the frayed Japan-Korea ties. Japan says it’s time to move on. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe recently reiterated that the current Japanese generation have nothing to do with past war crimes. But when you have Japanese broadcasters going out of their way to damage Korea’s reputation, it’s hard to accept anything Japanese officials have to say. I also find it difficult to accept the argument about freedom of press. It was not too long ago that the Japanese government came under fire for allegedly twisting the arms of a broadcaster to fire a guest who was too outspoken in denouncing the prime minister. If you’re curious, Google Shigeaki Koga and decide for yourself. Perhaps the Korean media also portrays Japan in a detrimental light. But these days, there are more programs and articles about how advanced Japan is, and the miracles it worked to extricate itself from a two-decade long recession. If there is any criticism, it’s concentrated on past colonial misdeeds and war crimes committed by Japan. Criticism by the media can never be restricted, and it never should be. But there is a fine line between blind bashing and constructive criticism. What I saw on TV Tokyo was far from the latter. By Kim Ji-hyun Kim Ji-hyun is The Korea Herald’s Tokyo correspondent. — Ed.

Originální článek : ZDE

0 notes

Text

A dávej si v té zemi bacha!

Nedávno jsem se vrátila z Japonska.

Konečně jsem měla šanci podívat se do té země, kterou mí japonští spolužáci tak glorifikují a přirovnávají jako k dospělému, slušnému a vychovanému staršímu sourozenci Koreje.

Vtipná prolínačka. Než jsem jela do Koreje, vzala si mě stranou má japonská zaměstnavatelka (ベビーシッターのバイト) a řekla mi, že není vůbec spokojená s tím, jakou zemi jsem si pro tak dlouhé studium vybrala. V Koreji je přece tolik znásilnění, není to bezpečná země.” (říká Japonka žijící v Česku?!)

O dva roky později. Japonsko, Maze. V kempu, kde pracuji, se potkám s Korejkou (vdaná za Japonce, dvě děti). Kecáme spolu, k znepokojení a lehkému mračení se okolních Japonců, korejsky. Paní se zamračí a “No, ale až pojedeš do Kjóta nebo Ósaky....tak si dávej pozor. Japonsko není Korea. Není moc bezpečné a mladým holkám se může po večerech stát cokoliv....”

Můj následný výraz v obličeji:

0 notes

Text

Jsou Korejci posedlí tituly? Jde o školu, nebo o život...?

Někdy mne zaujmou novinové články, které sice reflektují nějakou momentální kazu, ale odráží se v nich dlouho zakořeněný problém. Tentokrát jde o korejské školství. Pole problémy tak zaminované, že se do něj málokdo vůbec v debatě pouští. Kde začít? Jak to řešit? “Ach.” Pokrčení rameny a smutný pohled.

Scandal exposes Korea’s twisted obsession with degrees

Two weeks ago, a South Korean “math prodigy” made headlines across the country after claiming that she had been accepted into two prestigious American universities, Stanford and Harvard. Kim Jung-yoon, a senior at Thomas Jefferson high School for Science and Technology in Virginia, rose to fame after media reported that the top-tier universities had competed to recruit her to their undergraduate programs and ended up creating a special shared program only for her to study at both schools. According to the reports, the 18-year-old girl secured a rare chance to study at both schools and choose where to graduate from. Kim showed acceptance letters from the schools to back her claims. Kim was featured on radio talk shows while her father contributed to the hype by conducting interviews with local news outlets. The reports on Kim’s achievement sparked envy among Koreans who have been living in a climate where admission into top universities is seen as key to elevating their social status. But about a week later, her whole story was unraveled, with both Harvard and Stanford universities denying the acceptance of the Korean student. The universities confirmed that there was no such joint program allowing a student to study at both schools, calling the acceptance letters provided by Kim forgeries.

Kim, who appears to have masterminded the whole furor herself, immediately went from being idolized to ridiculed, with her father apologizing last week for causing a stir and promising to take care of her mental health. Putting aside the reason behind her scam, the scandal appeared to leave a bitter aftertaste here, as it bluntly illustrated the country’s avid obsession with academic elitism and a competitive media industry prone to lapses of judgment. A 28-year-old student said he could sympathize with her as he understands what it feels like to fail to enter top-tier universities and to be treated like a “loser” in Korean society. “I have felt that entering a renowned university is a way to have my voice heard in Korean society,” Lee, who wanted to be identified only by his surname, told The Korea Herald. Lee is studying for a master’s at a Seoul-based university after receiving a diploma from a lesser-known college. “When I criticize the social structure, people think that I am complaining due to my poor educational background,” he said. “Then, I become a loser again.” In Korea, it has been considered a norm that one’s diploma defines the rest of his or her life, from career to even marriage prospects. Cliques are formed based on educational backgrounds, with graduates from the nation’s top universities taking up high positions on the social ladder and dominating academia, business and politics. The infamous Korean helicopter moms enroll their toddlers in English-language kindergartens, in desperate hopes that the child will not be left behind in the fierce competition to enter the country’s best universities, or if not, prestigious ones abroad. Kim is one of the kids who might have felt pressured to impress her parents, said Seol Dong-hoon, a sociology professor from Chonbuk National University. “The whole hullaballoo could have only been a family issue, but Kim’s father made her lie public by showing off his daughter’s achievement through the media,” Seol said. Indeed, Kim’s case was only the latest in a long list of academic fabrication cases in Korea. One of the most high-profile scandals came in 2007 when Shin Jeong-ah, an art history professor at Dongguk University, faked her academic record. On the back of her distinguished degrees from Yale and University of Kansas, Shin rapidly shot to prominence in the local art world. She was appointed codirector of the Gwangju Biennale, one of the biggest art events in East Asia, at the age of 35. But Shin fell from grace when her academic accomplishments turned out to be forged. She resigned from all her posts and was eventually convicted of falsifying records and embezzlement. The Shin case triggered a wave of similar allegations and confessions across the nation involving a professor, movie director, renowned architect, leading actors and actresses and even a respected monk. Behind the academic fraud cases is Koreans’ belief that educational backgrounds indicate “status” in society, experts said. “Koreans have viewed an academic degree as a prerequisite to success and climbing up the social ladder, which has intensified competition for admission to prestigious universities,” Shin Kwang-yeong, a sociology professor from Chung-Ang University, told The Korea Herald.

And the belief has more than 1,000 years of history to it. “Back in history, only aristocrats had a chance to take a state-administered exam to rise in social status,” Shin said, referring to the Goryeo (918-1392) and Joseon (1392-1895) dynasties under which people took the Gwageo, the national civil service exam to advance into society. “But now, exams are standardized and institutionalized so that anyone in any class can take an exam, get respectable degrees and enter the upper tier of society,” he added. With the country’s leading businesses and key national exams still favoring those with prestigious diplomas, the obsession to embellish one’s academic record persists, experts said. A recent survey suggested that university degrees still have a huge impact on new graduates’ job prospects. According to a survey of 418 firms by recruitment site Saramin, 88.5 percent of the surveyed companies said that they have given an advantage to those holding a degree from renowned universities in the resume screening process. Asked about the reason behind the practice, the companies said that they saw prestigious degrees as a result of one’s efforts and a means of objectively measuring job seekers’ abilities. Other experts pointed out the Kim’s scandal was also a result of poor quality journalism. After it was found to be fabricated, a mainstream media outlet published a lengthy correction after having covered the teenage girl’s story. “Kim’s story had every element that can excite Koreans ― the success of a Korean abroad and acceptance into prestigious universities,” said Choi Jin-bong, who teaches mass communications at Sungkonghoe University. “That’s perhaps why Korean media hastily picked up the story.” With the news about Kim going viral in Korea after first being covered by a Korean newspaper in the U.S., the local media continued to reproduce the story until parents and students at Kim’s school raised questions about her credentials, which later prompted a local daily to check the supposed facts. “Amid fierce competition to attract readers and generate traffic online, local news outlets lack a system to check facts before reporting,” Choi said, pinpointing a structural problem of online journalism driven by “stimulating” stories. “Such diminishing media ethics can strike us all in the long run,” Choi added. Above all, the Kim case sounds the alarm to a society that has been pushing its youth to “risk their lives” to get into top-tier universities, said Kim Ji-ae, an activist campaigning to break academic cliques in society. “The 18-year-old girl is not the only one to blame. Korean society that has made a university degree a source of pride or inferiority should take the blame,” Kim said. “Kim’s behavior might be a self-portrait of us all.”

By Ock Hyun-ju ([email protected])

#koreaschoolsystem#koreaschool#koreasuffer#koreaškolství#koreaškola#korejskáškola#koreastudium#koreastudy#studyabroad#koreasuicide#SouthKorea#koreauniversity#koreablog#studentblog

0 notes

Photo

Můj výlet do hor...Dobong(san).Vyrazila jsem sama, ale než jsem došla dolů, měla jsem několik nových kamarádů, manželský pár, nějaké Němce, dva sportovce a jednoho dědu, co lezl i po Himálajích. Aneb, jak je jednoduché navázat konverzaci, když čekáte ve skalním převisu ve škvíře na moment, kdy se budete moci po řetězech přehoupnout mezi dvěma balvany)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Freed South Korean slaves now face misery in homeless shelters; some consider going back

Když jsem poprvé četla ten článek o Solných farmách, velmi mne zaujal (jestli jde o šoku nad krutostí a lhostejností Korejců, mluvit jako o zájmu.)

Můžete přečíst originál ZDE

A další články zde:

A living hell" for slaves on remote South Korean island salt farms

The islands of abuse: Inside South Korea's slave farms for the disabled

MOKPO, SOUTH KOREA – Life as a salt-farm slave was so bad that Kim Jong-seok sometimes fantasized about killing the owner who beat him daily. But freedom, he says, has been worse.

In the year since police emancipated the severely mentally disabled man from the remote island farm where he had worked for eight years, Kim has lived in a grim homeless shelter, where he has been preyed upon and robbed by other residents. He has no friends, no job training prospects or counseling, and feels confined and deeply bored.

“I want to go back,” Kim, 41, said during a recent interview in the shelter near Mokpo, the southwestern mainland port that is the gateway to dozens of salt islands where a months-long investigation by The Associated Press found that slavery still thrives, an open secret among locals.

“I feel trapped here,” he said.

Kim’s plight illustrates the continuing failure of one of Asia’s richest countries to help workers who have been enslaved on the farms — often people with mental or physical disabilities. Three other disabled ex-slaves also told AP that they wanted to return to the salt farms because of their misery and sense of aimlessness in the crowded homeless shelters that officials placed them in.

On the farms, they said, they at least had a fixed daily routine, a job they became skilled at and a sense of purpose. An official on Sinui, one of the salt-farming islands, confirms that at least one ex-slave has returned to a farm. Activists and officials suspect there are many more.

While the initial reports on slavery shocked many South Koreans and led to a nationwide investigation last year, “Society continues to fail in providing basic help for our most vulnerable members even after they were pulled out of slavery on the islands,” said Choi Jung-kyu, a lawyer whose office represents 18 former slaves. “Our society is treating the victims worse than the salt farmers did.”

Salt farmers often describe themselves as doing society a favor by taking in the homeless, the disabled, the uneducated and those who can’t get jobs anywhere else and whom the rest of the country would like to forget. They also acknowledge a harsh economic reality.

“It would be extremely difficult to run a salt farm without disabled people,” said Park Jong-won, 69, a salt farm owner on Sinui Island who recently received a suspended sentence for exploiting a mentally disabled man for profit. “Normal people wouldn’t work at salt farms even if we begged them.”

Prosecutors had sought a prison term for Park, but an appeals court showed leniency in part because it said Park provided the victim with “food and a place to stay.”

Revelations of slavery involving South Korea’s disabled on island salt farms have emerged five times in the last decade. Last year’s government probe found more than 100 workers nationwide who had received little or no pay. A later investigation by police and activists found 63 more such workers in the islands, three-quarters of whom were disabled.

The investigations began after Seoul police went undercover to rescue a disabled man who had written to his mother to say he was enslaved on a salt farm. That man, Kim Seong-baek, is expected to testify Wednesday in a Seoul court as his former boss appeals a 3½-year prison sentence.

Kim Seong-baek, now living in Seoul, has no desire to go back; he says even looking at salt disgusts him. But several other recently freed slaves interviewed by AP say they feel more hopelessness and fear than relief about their lives away from the salt farms. Most of them were homeless before being lured to salt farms by illegal job brokers hired by farm owners.

Kim Jong-seok, the former slave languishing in the homeless shelter near Mokpo, said that his ex-owner, who is being investigated for abuse but hasn’t been arrested, recently visited and asked if he would work for him again for about $90 a month.

Lawyers helping the victims said they are alarmed that some disabled ex-slaves are in regular contact with their former masters, but add that the law does not prohibit it.

Others released from slavery also struggle to fit into society.

Han Sang-deok was freed by police last year after 20 years working without pay on a salt farm on Sinui, the same island where both Kims had been exploited. Until his release, not once did the 64-year-old mentally disabled man leave the island, Han said in an interview at a cafe in Mokpo.

Asked about his relationship with the farm owners, Han said: “I just worked. I was there on my own. I went to work, I slept. Like that.”

Han, whose relatives had thought he was dead for two decades, paused for a long time when asked about his future plans, finally saying, “I don’t know what I should do.”

Kang Seong-hwan, an official at the Sinui Island ward office who is in charge of monitoring disabled workers, told AP that at least one salt farm slave had returned to his employer after being rescued last year. He said he has little actual power to check up on workers and suspects there are more cases of returned slaves because they have been essentially neglected after moving to shelters.

Activists trying to keep tabs on freed slaves often track down victims only to hear them say that they have returned to the salt farms and do not want to be contacted again, said Huh Joo-hyeon, the director of an activist group in Mokpo.

Park Su-in, Huh’s colleague, describes a system in which disabled workers on the islands become dependent on their owners for food and medical care, leading to exploitation. One disabled former slave she talked to didn’t know the words “password” or “bank account,” yet he had a bank account, controlled by his owner, where his disability payments were sent.

Amid short-lived public anger last year, regional government officials vowed to open an exclusive facility for the freed slaves and connect them with new jobs. The promises haven’t been kept, and activists believe there is little chance they will be.

Many of the ex-slaves are now in a bureaucratic limbo. Because they have been moved away from the islands in Sinan County, county officials say they can’t help the victims, don’t have the space for them anyway.

An official from the homeless shelter near Mokpo where Kim Jong-seok lives said freed slaves were supposed to stay there only temporarily, and wondered when Sinan County would take them back. The official said the facility barely has room for the homeless people in the area, and it is not their responsibility to provide job programs and counseling.

In some cases, guardians have been appointed to protect former slaves’ interests. One ex-slave, Heo Tae-yeong, has a guardian who orchestrated his move from a Mokpo area homeless shelter to a residential facility for the mentally disabled in Gwangju.

Heo, who cannot read or count, worries that he will struggle in a new environment, but is excited about the idea of learning job skills in Gwangju. He hopes to one day work in a factory.

When asked what he will do with the money he earns, Heo took a long drag off his cigarette. He didn’t know: “I’ve never had any money.”

#saltfarm#korea#koreaculture#koreaexcahnge#koreastudium#koreasociety#korealide#korejci#koreapopculture

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Pár foto z poslední doby.....

0 notes

Text

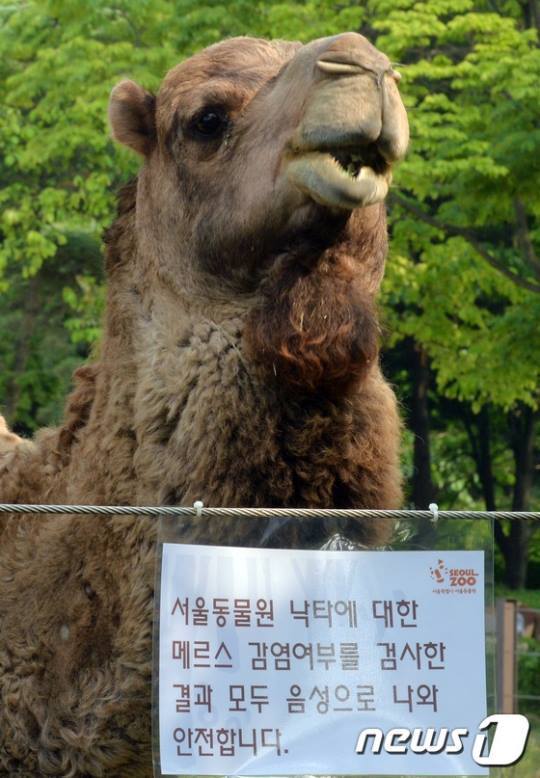

Velbloud: Já vám říkám, že já to nebyl!

(ze včerejších zprávy) Dva velbloudi, kteří byli kvůli hrozbě MERSu v karanténě, dle testu nejsou infikovaní.

Přesto je u nich v plánu 2 x denně vakcína a ošetření a celé Zoo, včetně ostatních zařízení, jsou i nadále dostupná veřejnosti (přesto lidí je, dle zpráv, všude méně a méně a Korea si stěžuje, že nemoc jim zasadila velkou ránu, obzvlášť na začátku léta a turistické sezóny.)

“Všechny test ohledně MERS nakažení velbloudů Seoulské ZOO vyšely negativně a nemusíte se ničeho obávat.”

(myslím, že za žádné jiné situace by se v koment-sekci nevyskytla taková vlna lásky a sympatie k velbloudům, kteří byli vystaveni kvůli celé aféře na pranýř. Ovšem na pranýři a ne zcela v bezpečí je muž, který nemoc do Koreje přinesl a poté doktor, jehož aféru už 3 dny rozmazávají v novinách, který, přestože vykazoval příznaky MERS, se účastnil dvou konferencí, rodinného obědu, nakupování a následné dny testoval pozitivně.

Jak se poslední dobou mezi Korejci ozývá...“욕먹게 만들어야 되...” Však vina na něj padne...

0 notes

Text

Korejská móda : připraven do hor v každém okamžiku!

Koukám (se zpožděním) na rozhovor “Zákaz outdooru: Oblečení na Milešovku do města nepatří” kdy v restauraci zakázali chodit do restaurace lidem v outdoorovém oblečení. A napadlo mne “Hehe, to kdyby bylo tady, tak ti do restaurace nepáchne nikdo.”

Proč? Zkuste se zde projít po venku tady v Koreji. Jen na chvíli. Viděli jste to? Jsem si jistá, že ano. Když to řeknu jednoduše, tak Korejci, obzvlášť ti starší, chodí hodně rádi v outdoorovém oblečení.

Mohla bych nad tímto faktem polemizovat hodně dlouho. Mohla bych upozornit, že se jedná o jeden z největších kulturních šoků, které jsem zde zažila a kdykoliv zde vítám jakékoliv nové přátelé ze zahraničí, často je tím prvním, co uvedou jako největší překvapení a šok “Hele.....hm.....proč chodí tolik Korejců v horském sportovním oblečení?”

Korea’s outdoor clothing climbing to fashion heights

Dobrá otázka, přátelé. Chodí snad opravdu všichni denně do hor (hmm, na kopec se projít platí taky?), jsou snad každou chvíli připraveni utéct do hor před nějakých útokem od Severních bratrů (kteří mají těch hor přece jen o poznání výší) Ptala jsem se, ptala jsem se stokrát a žádná odpověď, kterou jsem na to dostala ať už od korejských kamarádů, nebo od samotných starších generací, které to oblečení nosí, mne neuspokojila.

Prý je to pohodlné a navíc Korejci tak tuze rádi hory. A těch je všude tolik.

Ale to přece nevysvětluje, proč 80% strejdů, tetek a dědků s babčami se tady na ulicích blejskají v North Face, K2, Mammoth.........a není žádným překvapením, když člověk narazí na název titulku “Suited and booted: Outdoor clothing is Korea's new luxury wear” K čemuž musím dodat, že nic spolu neladí více, než staré korejské tetky s full make-upem, trvalou na hlavě, Lousi Vuitton kabelkou a oblečené, jako do prvního výškového tábora na K2.

Znáte nějaké K-pop idoly? Šance, že nepózovali pro nějakou outdoor značku je minimální. Samotnou Jun Ji-hyun (uh, mne to její jméno v angličtině fakt nesedí, nikdy nevím, o kom cizinci mluví. Už jen proto, že “Jeon”, ne “Jun” s účkem, se vyslovuje s ŏ... a proč je tam ta pomlčka, když je to jedno jméno. Jako kdyby mne přepsali Vero-nika. Ale proč se nad tím zamýšlím tady, safra....whatever). jsem viděla v několika outdoor reklamách různých značek, Big Bang si střihnul North Face, obzvlášť ty jejich krabicové batohy, co minulý rok měli snad všeci.....)

Jestli v tomto článku hledáte odpověďi, vysvětlení, nenajdete ho...já ho sama hledám pořád. Možná žádná nejsou. A možná se zamýšlím zbytečně nad hloupostí. Prostě tradiční korejská módní kultura z posledních let je horské outdoorové oblečení. A barevné, ano. Barevné.

0 notes

Photo

Abych sdílela i něco vtipného, dneska jsem narazila při učení na nový pojem.

술에 떡이 되다. Sul (alkohol)he, ddoki doeda (safra, nevím, jestli jsem transkripci trefila, spíš je to podle zvuku).

Aka opil se a stal se z něj rýžový koláček. Tedy, těch je tucet druhů, ale zde myslí shiru ddok, 시루떡, jak je zobrazeno na obrázku. Mno a význam je, jak už nejspíš tušíte, klasický.

Zpil se pod obraz. Ožralý jak doga...atd atd. Když jsem to poprvé našla, napadlo mne proč rýžový koláč? Ty jsou přece pevné a lahodné. Tak jsem si to vygooglila a vyskočil na mne tenhle obrázek. Pravda, když se shiru ddok vyrobí (dělá se tradičně na páře, jako naše sladké knedlíky), kouří se z něho, je měkký, ohebný....takže tak nějak sedí.

#chlast#alkohol#jídlo#koreajídlo#rýžovýkoláč#ricecake#ddok#koreastudy#jazykovázajímavost#jazyk#korejstina

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ááá máme tady další virus...

Novinky z Koreje. Hold to bylo už dávno, kdy jsme měli vlnu SARS a ne zas tak docela dávno, kdy tudma vládla panika z prasečí chřipky (a tu dostalo i několik slavných idolů....ale z těch přežili všichni. Ono se prý nakonec ukázalo, že to byl prostě horší typ obyčejné chřipky).

Ale tentokrát, dámy a pánové, máme novinku, MERS: (odborně MERS-CoV – Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus) je jedna z forem koronaviru. Patří do rodu Betacoronavirus podobně jako příbuzný virus SARS. Jde o virus způsobující závažné lidská onemocnění plic a ledvin. Je znám od roku 2012.

A jak ta panika začíná pomalinku. Nejprve jsem to četla v novinách, kdy to sdílelo několik mých kamarádů cizinců, se smutnými nebo naštvanými smajlíky a komenty, proč safra musíme žít v zemi, která to fakt nemají po hygienické stránce zvládnuté. No a potom, když jsem venku trávila sobotu s kamarádem, který byl zrovna na dovolence z armády, tak mu přišel telefon od velitele. Kontrolují všechny vojáky, nejprve tímto způsobem, telefonicky. “Ano. Měřím si teplotu. Ne, nepocítil jsem žádnou bolest, nebo zvláštnosti. Ne, nenacházel jsem se v poslední době v nemocničním prostoru. Ano, budu se i nadále monitorovat.”

Telefon položil a zatvářil se vážně. “Mno, nebude to sranda. Jestli to někdo od nás má, tak se to rozšíří hodně rychle...” -”Moment, já myslela, že to je zas jen takové....mno víš jak, panika pro nic.” -”Mno...ne, nevypadá to tak.”

Super výhoda nemocí. Jak se rychle šíří. Ono totiž od chudáka dědy, co to donesl, to chytli naprosto všichni, kteří s ním byli ve styku v nemocnici, spolupacienti a i ti, co se o něj starali. Jenže mezitím zdá se, děda běhal i po jiných zařízeních, protože když si poprvé přišel stěžovat s problémy, klasické korejské zdravotní zařízení do poslalo do šípku s pár tabletkami (tady by vám každý o tom řekl svoje). Člověk by si myslel, že země, která si tímhle prochází docela často, na to bude nějak lépe připravená, ale i teď se z internetu ozývají kritiky vůči vládě, že nedělá vše, co by měla, zanedbává hygienu a mezitím se strach a panika rozrůstají.

Bylo mi připomenuto, že mám nosit od teď radši venku roušku. To není zas tak problém, krom toho, že se mi v ní hrozně potí huba. Ale teďka budeme všichni po škole běhat s rouškou a rozděleni na skupiny “Co? Ty tomu věříš a jsi počůraná strachy, co?” a “Mno, já si radši myju ruce i 4x za sebou.”

Lidé jsou vyděšení z rychlosti šíření. Před pár dny byl titulek “Už 3 nakažení.” Dnes je titulek “Už 18 nakažených a 2 mrtví!” A teďka čtu úplně poslední korejské zprávy a nakažených máme 30, mrtvé dva a v obchodech došly ruční sanitizéry.

Na začátku to měl jeden děda, nemocnice tvrdila, že máš vše pod kontrolou. A za chvíli to měli všichni ostatní, následně i ti, co přišli s nimi do kontaktu a....těžko říct, co teď.

Mno, vzhledem k tomu, že já po venku chodit musím a tomuhle se stejně neubráníte (stačilo by, aby se moje spolubydlící třeba jen při procházce venku nakazila od nějakého děduli, co se s našim prvotním alfa dědulou potkal na recepci v nemocnici a máte smůlu. Hold, jdu si rozbalit svůj balíček masek a doufat, že to nechytnu.

Info Světové zdrav. organizace

S. Korea has frist two MERS deaths

Mers fear spreads

Že s tím korejská vláda nic nedělá

#tojezas#presnecojsemchtela#omluvanositmasku#virus#mers#korea#jiznikorea#studiumvzahranici#studiumvkoreji#koreastudium

0 notes