Writing on Beautiful Pictures A blog for reviewing, critiquing, analyzing, recommending, and gushing about visual and written media. Tumblr mirror of the Wordpress Blog.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

[Analysis] Even the Tiniest Bards: A Study of Two Leitmotifs in Wandersong

[Analysis] Even the Tiniest Bards: A Study of Two Leitmotifs in Wandersong

Wandersongis a delightful game about being a bard, singing songs, and making friends. Ever since I played it in January of this year, it has persisted in my head like a particularly catchy earworm. I’ve thought about it night and day for months, to the point that I could write probably a billion words of meta on just about every aspect of it, but it would probably be better for everyone to pick a…

View On WordPress

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

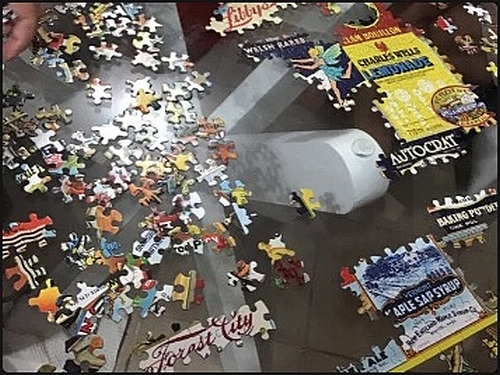

[Reflection] The Final Piece of the Puzzle

View On WordPress

I spent the new year at my cousin’s beach house, overlooking the warm waters of the Southern Brazilian coast. Inside the open plan kitchen/living room, cooled by the chilly ocean breeze, we gathered round for one of our old family pastimes: six pairs of hands, or seven, or eight, depending on who dropped in or out, deftly sorting through piles of tiny pieces, seeking out shapes, patterns, colors, snapping them together; little by little, a skeletal frame emerges, blocks of attached pieces sliding from hand to hand, a box passed around the circle, an auntie asking “does anyone have this corner?” — from a jumble of one thousand units, a picture comes together within a few hours. Someone presses down on the final piece, locking it into place. We take a moment to appreciate the results of our efforts, congratulate each other on a job well done, and then tip the board back into the box, scattering the fragile creation into its constituent parts.

This memory of communal jigsaw puzzle solving goes back as far as my conscious awareness can reach. Almost every family function involves a coffee table spread out with a freshly opened puzzle box. Sometimes everyone sits down to solve it, but often it’s left as an open challenge, with solvers drifting towards it in between coffee, cakes, gift exchanges, and naps. It could take hours, or it could take days, but eventually it is finished at whichever leisurely pace it requires.

In an old home video, a 2-year-old me delightfully solves a wooden toddler puzzle, excitedly showing off my skills to my parents. From then until this most recent holiday gathering, puzzles have been a part of my life, whether they be jigsaws, logic exercises, sudoku, or videogames. Beyond the thrill of intellectual challenge, puzzle-solving is intertwined with a sense of community and belonging. It’s as much about getting together with loved ones to solve a problem together as it is about solving the problem itself. Some families play games, some watch movies, ours solves puzzles. It’s how we enjoy each other’s company.

As I write this, it is April 2nd, Autism Acceptance Day. On this day, and throughout the month of April, autistic people warn of the dangers of Autism Speaks, an organization that treats autism as a disease to be eradicated, as opposed to a neurotype inseparable from our own personhood. Among its many problems, Autism Speaks uses a puzzle piece symbol, historically representing autism as “a puzzling disorder”, at other times evolving into other meanings, such as “the complexity of treating autism”, “the diversity of autistic people”, “the missing part that makes autistic people incomplete”, “trying to put together the pieces of the disordered mind”, “solving the mystery of autism”. Regardless of what meaning is in common usage, the autistic community rejects this symbol; with few exceptions, the negative connotations are too great, its iconography too closely associated with an organization which has done us far more harm than good.

This breaks my heart.

I know my individual feelings can’t erase the damage this symbol has done to our community, or the hurt it has caused my fellow autistic friends. Even I take a step back whenever I see a puzzle piece, suspicious of the intents of the user, as it often indicates someone who hasn’t taken the time to talk to and understand autistic people. But the puzzle piece is a symbol so special and significant to me, I want to open up a space to reclaim my own meaning.

When I think about being autistic, I don’t think about the difficulty recognizing people, the overwhelming sensory sensitivity, or the auditory processing issues requiring subtitles on most things I watch. Those are part of my life, sure, but they’re not “me” — not like the drive to research a special interest, the excitement of infodumping, or the elation when I see an airplane fly overhead. It may be a cliche, but those traits that make me a so-called “little professor” are the defining traits of my autistic experience, and suppressing my autistic traits suppresses everything I love about being myself.

That includes the puzzle piece.

I can see my traits in my paternal lineage. I don’t know whether my family is autistic, or if they would ever identify as such. It doesn’t matter to me, because when I’m around them, solving a puzzle, that’s when our bonds are at their strongest. It’s about problem solving, but most importantly the pure enjoyment of immersing ourselves into a meticulous task, the meditative quality of a good hyperfocus. When we solve a puzzle together, we are materializing the traits that make us who we are: people who care deeply about something and then give that something everything we have. We are not “putting together the pieces of a broken mind” — we are using our uniquely developed minds to put together the pieces of the things we love. We are creating.

It’s discovery. It’s pattern-seeking. It’s making something happen purely because it gives us joy. The finished puzzle never stays that way for long. It doesn’t have any practical use. In it goes, back in the box, hours of work breaking apart, because the joy wasn’t the end result, it was the process. And the process is what I love, and the process is who I am. Whatever I am doing, work, school, or personal projects, I find my pleasure and fulfillment in the process; hammering out the details is a pastime, not a chore. It’s the drive, the repetition, the coming back to something left unfinished, the letting the mind decide what it wants and then letting it be.

I know every autistic person is different. Many people will not share my experience, and that’s okay. But rather than focusing on what I am not, I want to focus on what I am, and I think many people can relate to the idea that passing for neurotypical means severing the parts of us we love. For me, that means pretending that I don’t love sinking myself into a task that requires sorting through mountains of identical-looking pieces. I have to avoid looking like I pay too much attention to any one given thing, because that’s obsessive, inflexible and bad, and to shut up about my special interest because everyone’s sick of hearing me go on about a subject nobody understands. This is what the misuse of the puzzle piece symbol feels like to me; shut up about the positives of autism, we want to medicalize your neurotype and strip away what makes your life enjoyable.

Look, it’s not easy, I get it. I don’t enjoy meltdowns or sudden nonverbality or being unable to rip myself from a task to the point of starvation or misreading a social situation so badly I humiliate myself. But among autistic people I’m normal, we understand each other as fluidly as allistic people understand each other, and I am sure an allistic person living in an autistic-only world would feel just as disoriented. It’s contextual, and the context of our stories and our symbols depends on who is scrutinizing us and why. If Autism Speaks represents a shadow over my community, and the puzzle piece represents our dehumanization, I can’t do anything to change that. But I can keep puzzles to myself.

Because the joy of my life is all about sitting around a table at my cousin’s beach house, and the moment someone presses that final piece of the puzzle into place.

Photo: The partially completed puzzle we solved over the holiday break.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Analysis] BanG Dream! — Visualizing Progress with Videogames

View On WordPress

When I’m depressed, I like to play videogames.

This probably seems like a mundane statement; it makes sense that someone would want to do something fun or look for a form of escapism when they’re down, and videogames are one of the best ways to do that, as they are designed to be engrossing.

It’s true that sometimes all you need is a bit of fun to destress and cope with a tough day, but when it comes to Depression, big-D, Clinical Depression, things are not so simple. What would normally be casually entertaining can become completely joyless or unimaginably exhausting, as the brain is drained of its ability to focus, process information, or even feel emotions at all. A person with a mental illness can easily become caught in a downward spiral where the more difficult things get, the harder it is to pull out of the depressed state.

Many times I’ve caught myself feeling so depressed I couldn’t even bring myself to watch a movie or play a game, a problem compounded by the fact that since those things are entertainment, they are “unnecessary to survival” and therefore I shouldn’t waste my time on them and instead try to do chores or cook a meal.

(Note: it is always a good idea to take care of physical needs first when dealing with a brain crisis.)

However, videogames provide me with something that I’ve come to see as essential to my self care: they are a tangible way to prove that things CAN change, provided you put enough effort into it.

The difficulty with self-improvement is that day-to-day progress can be practically invisible. I might be able to look back at where I was two or three years ago and say, “well, I guess I’m doing better now than I was then”, but actually seeing the work pay off can take even longer. Sometimes it feels like nothing is going forward at all, that all attempts have failed, or that progress has stagnated and one is going in circles rather than up. When the evidence is hard to see, Depression can take hold even deeper in the brain, whispering, “nothing will ever get better — you might as well give up now.”

I have found that videogames effectively counteract this particular brand of depressive self-talk because their very nature means progress is built into the design. Some games are more focused on this than others; some are not concerned with skill at all and merely wish to deliver a story or experience, and that’s useful too for other types of self-help, but when I want to prove to myself that progress is possible, I seek games that contain at least some level of skill-based challenge.

I’ve mentioned before, but I am abysmally bad at playing games. My reflexes are slow, I am easily confused, and my motor coordination is all over the place. Because of this, I generally avoid rhythm games. They tend to frustrate me more than anything else, and yet somehow, the mobile app game BanG Dream! Girls Band Party, popularly known as Bandori, has become my go-to Depression Game over the past year.

There are a few factors that make Bandori unique as far as my distaste for rhythm games goes. For one, it has a fantastic assortment of characters, rich and complex relationship dynamics, and beautiful, nuanced writing. Another factor is that some of my friends were already fans of the Japanese version before the English version was released, and through them I got to know the cast and the world without having to worry about being good at the game. It certainly helps that the game features covers of popular anime songs I was familiar with and enjoyed. And thematically speaking, the fact that these 25 main characters are divided among 5 bands, each with its own particular genre, style, worldview, and approach to playing music, makes for an excellent microcosm of what it’s like to struggle with self-improvement. Many of the storylines revolve around practicing songs, learning how to play new instruments, trying out different techniques that don’t always work out, discovering new talents, or failing at them, and throughout it all, the bandmates support each other and encourage experimentation, hard work, and tenacity.

Of course, the plot isn’t the only thing that keeps me going with Bandori; it is, after all, the gameplay that concretizes these themes into something that I can physically digest. I started off, like an absolute noob, on the easiest difficulty for every song; the game rewards combos above 50 at this difficulty, yet I struggled to hit even 10. A full combo, the highest reward, seemed completely out of reach. I felt embarrassed joining multiplayer with my awful skills, but what I found was a friendly and eager community (it probably helps that there is no way to communicate aside from display names and stickers). The game scales difficulty, so even though I was clearly the worst player, I still contributed something valuable to the score.

It was this way, with patience and rewards, that progress slowly unfolded. After a couple of weeks, I was hitting those 50-combos. The day I finally got a full combo on Easy, I felt ecstatic at my accomplishment. I started dipping my toes into Normal difficulty — and immediately got hammered down to square one. But it was okay. I worked my way up again. I somehow hit the 100-combos. I got my first full combo on Normal and I felt invincible.

None of this is about my actual skill at the game. If I hadn’t made it that far, it still would have been fun, but what Bandori gave me was far more valuable than a reward for a full combo. It gave me a quick, easily accessible way to see just how dramatically I could improve at something in just a few weeks, in other words, showing how practice could help a skill develop in a short enough timeframe that such progress was undeniable. Most dimensions of self-improvement advance at such a glacial place that it’s easy to dismiss them as futile; Bandori is a reminder that yes, despite what Depression whispers, actions have consequences, cause and effect still exists, and the effort I put into myself may be invisible now, but down the line I’ll be hitting those metaphorical full combos, and it’s going to feel great.

Best of all, it’s going to feel easy.

There’s only one song I can play on Hard, but I’m happy now. I don’t need to struggle uphill against my nature because I already got what I wanted out of this game. I’m not the best player, but I got better. And I can probably still get even better.

Now it’s time to get to work.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Review] Tales of Vesperia: The Brightest Star in the Night Sky Doesn't Shine as Strongly as I'd Hoped

View On WordPress

Warning: Contains allusive/thematic spoilers.

The day is finally here! Tales of Vesperia: Definitive Edition, containing content previously unseen outside of Japan, has finally been released, so that us English speakers and/or non-PS3 owners can experience the new storylines, characters and features for the first time! Alas, this isn’t a post about that, firstly because this post is going up day-of-release and I haven’t had a chance to play it yet, and secondly because I am writing this from outside of the country and won’t be united with my pre-ordered copy until I return next week, RIP.

Therefore, this post is written from the point of view of someone who has only played the Xbox 360 version. I will try to keep it brief for the sake of not spoiling newcomers to the game, and also hopefully not to complain about things that are fixed (or broken??) in the Definitive Edition.

Tales of Vesperia is a game in the long-running “Tales of” franchise from Bandai Namco, the first one in HD, originally released for the Xbox 360 in 2008, later receiving an updated PS3 version in 2009, exclusive to Japan. Like many older fans, my introduction to the Tales of series was with Tales of Symphonia for the Gamecube, and I fell in love hard; I was therefore extremely excited to play the next games, but unfortunately, I never owned the platforms for them until very recently. Along with Tales of the Abyss, Vesperia and Symphonia form the “holy trinity” of games in the series almost everyone loves; find a Tales fan and ask them their favourite game, and the answer will likely be one of those three (note: I’ve heard very good things about Graces and the two Xillia games, but unfortunately haven’t had a chance to judge them firsthand myself). The three games, while not directly related in terms of plot or setting, share a lot of things in common, as they had mostly the same creative team, often referred to as “Team Symphonia” (as opposed to “Team Destiny” which made most other games since then). One notable difference is the scenario writer, Takashi Hasegawa, while Symphonia and Abyss were written by Takumi Miyajima.

The Tales series is known for its reliance on anime and JRPG tropes, often used in a way that plays off cliché expectations only to then layer plot twists and character development and produce a much deeper experience than what would be expected from the get-go. When used effectively, these methods produce a story that is both fun and emotionally challenging. Tales of Vesperia is no different, offering a cast of archetypes that should be highly recognizable to those familiar with the genre, and yet this may be best set of characters in a Tales game. The party has impressively good banter, chemistry and dynamics and several scenes had me laughing out loud or yelling, and I never had a bad time watching their relationships unfold.

Unfortunately, the game spares little time fleshing out backstories or learning more about each individual character outside of the main plot. By the end, I was left wanting, as the cast was so endearing and vibrant, yet I knew next to nothing about them aside from what had been relevant to show onscreen. I longed for more information about where they had come from and how they had gotten where they were, but it is a testament to the strength of the character writing that their storylines reached a satisfying conclusion despite this relative sparse amount of information about them. “Backstory is not story”, Craig McCracken and Frank Angones were fond of saying to fans of Wander Over Yonder, but for a game with the size and scope of a 60-hour JRPG, not providing that window of information feels like a hole in the worldbuilding.

Mechanically, Vesperia builds on the model established by Symphonia and refined in Abyss, where combat takes place in a 3D arena and the player can run around, hit enemies and rack up combos fighting game style (the franchise calls this “Linear Motion Battle System”). While Symphonia was in 3D, it restricted the player to a single side-to-side corridor of action. Abyss added the ability to run around in 3D space by holding down a button, a feature Vesperia also has. This makes combat easier and more fun, as nothing is quite as satisfying as avoiding an attack and then running around and hitting the enemy from behind. And, as the game allows up to four players controlling different party members, and I have a player 2 (shoutout to my roommate Opal), Vesperia’s system is the most well-suited to multiplayer. If nothing else, I never felt lost while on the battlefield yelling for backup. The one major flaw is that boss fights come with massive difficulty spikes and I often had to grind and formulate careful battle plans with Opal just to not get continuously massacred by bosses.

Storywise, Vesperia starts off very strongly, sort of peters out near the middle, and then the third act falls apart. At first the theme is anti-authority, with a protagonist who grew up in the slums, neglected by nobles, who became a knight and then quit out of disillusionment when it turned out all they did was squabble about politics, and the inciting incident and early driver of the plot is his quest to “fix the plumbing” as a popular Tumblr text post put it. It’s clear Yuri has all the reason in the world to not trust authority and he even goes full vigilante against unjust abuse of power, but while this thread seems like the most important theme in the story, after a while so many other elements come into play it ends up lost and doesn’t really make much of an appearance except to highlight the differences between Yuri and Flynn’s approaches to life and how they prefer to help people. On its own it’s a compelling idea, but it never gets the follow-through it deserves, and my expectations were certainly subverted—but in a bad way.

It’s hard to talk about the third act without spoilers so I will probably come back to it for a proper analysis at a later date, but its ultimate message was already kind of limp in 2008 and is even more laughable now. For a game whose initial premise was so strongly against authority, the ultimate resolution of the main conflict reads as incredibly daft in light of just about everything that is happening in politics at the moment. There’s a very strong environmental allegory and the comparisons to climate change are not subtle, but the writers probably bit off more than they could chew because realistically trying to solve this problem in the time the story allotted would have been next to impossible; I still would have hoped the implications of the given solution had been actually explored instead of settling for an “oh well, guess everything’s been fixed now”.

I’m being harsh about the plot because to me Vesperia has a lot of wasted potential. Don’t get me wrong: I do love this game. It is in fact up there with the holy trinity as far as my opinions of the series go, but it lands in third place out of the three because it just fails to live up to what its first half promises about the world it created. To put it bluntly, if the story had just ended at the conclusion of the second act, it would have been much stronger. That the game continues for another 20 hours on a completely different track with an unsatisfying, unrealistic conclusion is a huge shame because it brings down what could have been a real masterpiece of tropey anime JRPG narratives. I live for that stuff, there’s a reason I want to play every Tales game, but that’s what makes this letdown the most disappointing. At least the characters themselves get good conclusions; it is unfortunate I can’t say the same for the main plot.

Despite all this I think Vesperia is a worthwhile experience, and one of my favourite things about is its aesthetic sense. Every location is immersive, polished, and the pinnacle of what I want to see in a videogame, to the point I dream of Symphonia and Abyss remakes made in the same style (and every other game in the series, to be honest, but that seems unlikely with the direction it’s taken since then). I genuinely cared about the party and I wanted to see them succeed and I was ultimately happy that they did even if I did roll my eyes a lot. The combat was so satisfying and so fun to play with a player 2 it makes me twice as mad that Zestiria’s camera goes completely wild during multiplayer and prevents me from joining in. I should note that for someone who plays as many games as I do I am notoriously terrible at them so I heavily favour story over mechanics, but Vesperia is a game that reminds me that engaging gameplay can make a huge difference. Yeah, I suck, but at least I’m having fun while sucking. That’s more than I can say for a lot of games.

If you like JRPGs, games that let you run around and hit things, or fun and intriguing character dynamics, you’ll probably like Tales of Vesperia. If you’re looking for a coherent story from start to finish, you’ll probably disappointed, but there’s just enough there to keep you engrossed until the end. Overall, Vesperia is solid, and the parts it fumbles aren’t bad enough to ruin the whole thing, but hopefully the extra content in Definitive Edition helps to smooth it out; I’ll have to find that out for myself.

Aside from how it messes up the voice acting this time around. Oh, Bamco.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Analysis] The "Weird" One: Where The Last Jedi Fits

View On WordPress

I have a confession to make.

This may be a weird way to start what is essentially the first post of a new media critique blog, but I consider it to be essential knowledge. Every reviewer and analyst brings their own unique perspective to their writing, and I am no different; sooner or later, this truth will make itself known. To know this fact about me is to gain a new understanding of what makes me tick as a consumer of art, and it is one that it best to get out of the way as soon as possible, for it is better for a reader to lose interest now than to string along until the awkwardness of hiding such a secret reveals itself.

Here it is:

I LOVE the Star Wars prequels.

Oh, not only do I love them, completely and unironically, I actually do not care much for the original trilogy. It’s all right. But it doesn’t make my heart sing.

Attack of the Clones does.

Okay, okay, I can already hear the groans of disgust and the clicks of mice leaving my blog to the wilds of the web, but I promise this is going somewhere. I am not unaware of the many flaws the Prequel trilogy has, and I can’t in good conscience call them cinematic masterpieces, but I think this opinion derives itself not from poor taste, but the relative lack of blockbuster quality movies that tap into very particular themes and structural quirks that I appreciate. I may dive into those specifics at a later time, but the reason why I am bringing this up now is because it inextricably ties into my feelings about the most recent film in the franchise’s main series, which would be impossible for me to discuss without addressing this aspect of my formative film influences.

The Last Jedi has already received tons of coverage, controversy, and counter-controversy, so if you’re interested in picking apart the finer aspects of the plot and characters, feel free to look those up — I am sure there is a brilliant video essay on Youtube tailor-made just for you. I am more interested in the meta-narrative surrounding its position in terms of fanservice to what is an enourmous empire of not only fans of the original trilogy, but fans of its many derivations, spin-offs, and cultural foundations.

Star Wars is no longer just a film about a space farmer who learns he’s a space wizard and goes on a perfect beat-by-beat hero’s journey. It encompasses more than that: two sequels, an expanded universe of books upon books, comics, videogames, pinball machines — a holiday special (and no, I have not watched it) — toys, cartoons, parodies, reiterations, iconic images, phrases, cinematic touchstones, and, of course, the Prequels.

When the new Sequel trilogy was announced, the filmmakers had a real challenge to contend with: How can one follow up on not only a legacy of films, but also a legacy of expectations of what such a sequel would be like? I am not just referring to the fact that Disney, post acquisition of Lucasfilm, decided to just toss out the previous expanded universe, label it “Legends”, and start afresh with a new canon. I am also referring to the literal millions of fans who were already thoroughly familiar with not only the films but also their cultural impact. How could one possibly please them, especially when the Prequel trilogy was so universally mocked?

It was clear that Disney needed to win the crowd over, and to do so they leaned heavily into a safe bet: the Original trilogy. The Force Awakens released with a sort of wink-and-nudge, reflected in its story beats, characterization, and practical effects, that said “hey, we hear you. We know you’re scared because you don’t trust us to do this material justice and we know you love the original films, so we’re gonna give you exactly what you’re looking for”. It’s hard not to see the fanservice and whether or not it was successful has already been discussed to death, so I won’t get into it here, but the point is — and I am sure this wasn’t really intentional — to someone like me, who actually liked the prequels and a lot of the expanded universe, this approach felt incredibly alienating. Everyone was having fun with the new film, but to me it felt like it was saying, “all those things you love about Star Wars are not the reasons why anyone else loves Star Wars,” and I’m not gonna lie, I was pretty hurt, but at the very least The Force Awakens gave me a cast to fall in love with.

This is why when The Last Jedi was in production, I was intrigued to hear that this film was going to be “weird” and “unlike any other Star Wars film”. My expectations were tempered by the fact that ultimately this was going to be a Disney movie anyway, so it was probably not going to reach my standard of Weird (my dad showed me Koyaanisqatsi when I was 7, to give you an idea). Nevertheless, after the very safe rehash of Episode 4 that was The Force Awakens, I was just hoping for anything that might show me the franchise still had room for creativity.

I was in fact happy with the result, although it doesn’t surprise me at all that it attracted controversy. Some of my close friends, whose opinions I highly respect, hated the film for various reasons and I can even agree with them on some points. Others, like me, loved it. Overall, however, what I like most isn’t necessarily anything about the film itself, but its position as a nod to fans who wanted their corners of the Star Wars universe acknowledged. To put it bluntly, as a Prequels fan, I felt represented.

Going even beyond the Prequels, The Last Jedi contains themes from my favourite piece of Star Wars media, the Bioware-produced videogame Knights of the Old Republic and its Obsidian-produced sequel, which layer critique of what it means to be a Force user and what the role of Jedi and Sith are in the grand scheme of things. “Jedi” does not necessarily mean “good”, a fact Luke highlights in his role as reluctant mentor to Rey, and while there are some things I would change about his portrayal here, this perspective is absolutely one I wanted to see more of in the main series. Even as a kid, good-vs-evil stories bored me; it’s one reason why the Original trilogy failed to speak to me, because even though I wouldn’t have been able to articulate why at the time, the setup was just too easy. It didn’t challenge me to think that there’s a side that’s inherently good and a side that’s inherently evil, but when Knights of the Old Republic put decisions about when and how to use the Force in front of me, that was a much more interesting proposition, and the idea that doctrine about the nature of the Force could be wrong or even damaging was outright enticing. I honestly can’t remember whether playing the games or watching the Prequels came first, but I get the feeling it was the games, because that malleable view of what the Force means and who the Jedi and Sith are has carried through for me ever since.

The Last Jedi does kind of play it safe in some ways, ultimately being a Disney property that has to sell lots of merchandise and bring people to theme parks, but it also boldly rejects just about every expectation one might have of a “Star Wars Film”, characters make mistakes, they fail, things go wrong at the worst possible times, some act selfishly or foolishly, and by the time the credits roll there’s actually very little to be excited about, as the heroes are in a much worse position than they were when the film started, which was already very bleak. But in a way, that was the most exciting part to me, as someone who grew tired of the popular culture perception of Star Wars and who felt shut out of the Sequel trilogy by its first film; The Last Jedi may have been agonizing, but it was agonizing in a way that promised more, giving hope to those of us who were looking for a less straightforward narrative at a time when powerful politicians can be comically villainous in public and yet people would bend over backwards to excuse their actions as if an “evil empire” didn’t already exist. Over the last couple of years I have seen people post a gif of Padmé Amidala’s iconic line, “So this is how liberty dies… with thunderous applause”, saying this was the only part of the Prequel trilogy that aged well, and yet to me the truth was already glaringly obvious back when the film was released, contributing strongly to my own critical interpretation of it. The Last Jedi is a film that picks up on the thought that people can make foolish and terrible decisions and runs with it, but it is by no means the first in the series to approach this theme.

(I should note that as a Brazilian, whose country was freshly out of a dictatorship when I was born and which is now hurtling towards another at full speed, my views on what counts as an Evil Empire and how and why a democracy dies may be somewhat sharper than the average American’s. This is by no means the only reason why I’m into this kind of storytelling, nor is it exclusive to me, but it is a big one, and it would be short-sighted to ignore it.)

Ultimately I understand why The Last Jedi is so polarizing; it doesn’t pull punches and some of the punches it throws are even a bit misaimed, thus the description of it as “weird” and “unprecedented” makes sense. It just isn’t quite as weird or unprecedented when compared to previous attempts at broadening the scope of the Star Wars narrative both within the main film series and the expanded universe (at least pre-Disney; I haven’t engaged with any post-Legends canon aside from the Rebels cartoon, so I can’t say for sure). It also serves as a complete 180° turn from the Sequel trilogy establishing itself as a safe haven for Original trilogy fans and a middle chapter leading into a final film we still know nothing about, so whether its narrative leaps will pay off are still a mystery. In any case, The Last Jedi rejects superficial concerns in favour of theme, leading to a certain degree of dissatisfaction from fans who really wanted to know Rey’s parentage and what exactly was up with Snoke, but I think this is a good thing, because they gave new meanings to previously established Star Wars tropes and drove the whole thing into uncharted territory. I for one am glad the franchise has freed itself of these particular burdens; it simply remains to be seen whether the conclusion will maintain this momentum.

All this to say, I like the Last Jedi because it likes the things I like about Star Wars, and now I know I’m not the only one.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Introduction

[View on Wordpress]

Welcome to KALEIDOGRAPHIA, the blog about writing on beautiful pictures! And also things that aren’t pictures, because why limit myself?

Essentially, I like to write essays about media, so this will be the website where I post them. I also have a Tumblr mirror and a Twitter account, so feel free to follow wherever you wish.

What will be covered on KALEIDOGRAPHIA:

Subject matter: Mostly visual media, especially animation and videogames, as those are my areas of expertise, but also live action film and television, literature, audio, and whatever else I feel like covering. “Animation” will include film, TV cartoons, anime, and independent animation.

Reviews: An impression and overall response to a piece of media with an eye towards evaluating quality, will be marked as “spoiler” or “spoiler-free” as appropriate.

Critique: More in-depth evaluation than a review, critiques will seek to establish what the goal of the piece of media was and how successfully it achieved it, using art and literature as tools. Will almost certainly contain spoilers.

Analysis: Going beyond a simple evaluation of quality, the analysis seeks to understand a theme or purpose of a piece of media and locate it within a cultural or historical context. Rather than focusing on the piece in isolation, the analysis explores its relationship to real-world concepts.

Recommendations: Suggestions of media worth looking into, hopefully of high quality, but not necessarily; media of lesser quality may be recommended if it contains elements that are novel, interesting, or done in particularly unique ways.

Gushing: Sometimes a person just has to tell the world just how much they loved something.

I hope you like reading KALEIDOGRAPHIA. Updates are scheduled for every Friday but may also occur at other times if interesting opportunities present themselves. A podcast is also planned, to be released on the 13th of every month (but not this one because I am currently outside of the country). Podcasts will have available transcripts and essay posts may have audio versions in the future as well.

-QU

2 notes

·

View notes