Text

Public backlash to #AskSeaWorld campaign

Blackfish, a controversial documentary created by CNN in 2013 exposed the inhumane and callous living conditions that killer whales endure at SeaWorld, Orlando. The film is focused on Tilikum, an orca who has killed three whale trainers whilst being encompassed at sea world and is forced to perform and live in an exceedingly small scale enclosure (Tucciarone, 2016). Consequently, Sea Worlds’ organisation has been under fire on social media from the general public, animal activists, celebrities and various animal rights groups ever since the documentary’s release. The company suffered an 84% drop in profits shortly after Blackfish was aired (Arthur, 2016). SeaWorld did not formally respond to the critics generated from Blackfish on social media for over two years, until they finally broke their silence in March 2015 which is when their social media mayhem began.

SeaWorld launched a social media campaign on Twitter to rebrand their corporate image they called #AskSeaWorld. The tag line was ‘You Ask, We Answer’ and their digital strategy goal was to encourage Twitter users to ask questions about the care of killer whales and receive answers directly from the organisation (Arthur, 2016). However, the Twitter campaign entirely backfired, generating widespread social media backlash and gaining the attention of celebrities and powerful animal activists groups such as People for Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA). Animal right campaigners hijacked the hashtag when it was first released (Pemberton, 2015). Their marketing campaign was created to dissuade critics, but instead it fuelled their anger and increased even more unwanted attention (Lobosco, 2015).

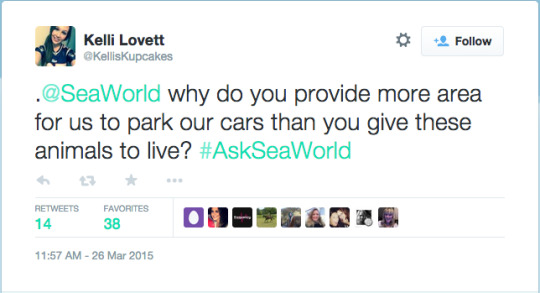

The #AskSeaWorld movement received 112k tweets just in the first five days of the campaign, and hashtag responses began trending such as #ThanksButNoTanks and #AbusementPark (Pemberton, 2015). Twitter critics utilized the #AskSeaWorld hashtag to their advantage by gruelling SeaWorld and instead of relating their questions to animal care, the questions were demanding the company to close down and release the orcas back into the wild. SeaWorld’s attempts of crowdsourcing entirely contradicted their main objective of involving Twitter users in their campaign. Many of the twitter responses sarcastically targeted the dropped shares that the company suffered consequent to the Blackfish documentary (Pemberton, 2015).

Significantly, SeaWorld’s response to the negative attention generated by its campaign exacerbated the situation and tarnished their reputation even further. When angry critics did not receive any responses from SeaWorld, and the hashtag #AnswerTheQ started trending, SeaWorld tweeted “we are trying to answer your questions but we have a few thousand trolls and bots to wade through #AskSeaWorld” (Lobosco, 2015). Furthermore, when animal activists hijacked their hashtag, SeaWorld tweeted “Jacking hashtags is so 2014 #BewareOfTrolls” (Tucciarone, 2016). Professional social media management was somewhat absent it would appear.

The key factors

youtube

The initial factor that contributed to this social media failure is the Blackfish documentary itself that was released by CNN and later Netflix in 2013. Blackfish exposed powerful and distressing footage of three human deaths, separations of calves from their mothers, the unimaginable small sizes of orca tanks and the danger to the trainers themselves (Arthur, 2016). The documentary argued that all of the killer whales in captivity showed signs of severe depression, which was proven by the fact they all had collapsed dorsal fins (Pemberton, 2015). The documentary which was primarily focused on the orca named Tilikum was suggestive that captivity had driven him to madness which ultimately led to the death of three human trainers (Martinez, 2014). SeaWorld responded to Blackfish producers by arguing that it was “shamefully dishonest and deliberately misleading” (Sola, 2015). Unfortunately for them, many ex-employees took part of the documentary who argued against SeaWorld which further validated the points made. SeaWorld consequently lost 84% in profits, the CEO at the time resigned and Blackfish had set them up for catastrophic failure (Arthur, 2016). Therefore, any social media campaign was inevitably going receive widespread abuse and condemnation.

A major factor contributing to this social media catastrophe is the incapability to manage a media crisis presented by SeaWorld. The inability to handle the huge volume of complaints and being argumentative back to twitter users is a crucial reflection of the organisation. Thus, Marwick argues that “strategic online self-presentation plays an enormous role in increasing ones status” (2013, p18). Self-presentation and self-promotion are key to maintaining popularity and appealing to as many people as possible (Marwick, 2013). However, SeaWorld disregarded this and instead opted to attack their critics which subsequently damaged their already poor reputation. SeaWorld’s aggressive and unprofessional response to ridicule their critics brought even more attention to the already failing campaign.

Furthermore, it can be argued that SeaWorld did not choose the correct platform for their campaign. Light (2014) states that Twitter is the most effective way to create and share information instantly within the public sphere. Twitter, as a social media platform, is now part of a genre of journalism and culture of short news articles (Hurcombe, 2017). Thus, news articles are susceptible to rapid spreadability and becoming well known among Twitter users. Twitter has the capacity to considerably influence a company’s reputation, financial prospects and even survival because it encourages possible negative public discourse (Kietzmann et al, 2011). With this in mind, SeaWorld should have been aware of the criticism they would inevitably face after the release of the documentary Blackfish. It was undoubtedly a tactical move to encourage the participation of Twitter users as a marketing strategy but SeaWorld had a misplaced expectation, and they soon realized it is much easier to engage critics than fans. By utilizing Twitter as a social media platform, SeaWorld had no protective barriers, making them vulnerable to shareability and consequent widespread negative responses.

If I was in charge?

If I personally was responsible for the social media strategy of SeaWorld I would have approached the situation in several different ways. I believe one of SeaWorld’s main faults is that they did not consider the audiences reaction when they were asked to partake in a social media activity. It is pivotal to create a crisis management strategy and response framework in order to prepare for mass criticism (Cassidy, 2017). I would make a list of testing questions with reasonable answers in preparation and ensure to respond to them as quickly as possible. Instead of attacking critics and publicly shaming them as ‘trolls’ I would accept their disapproval and offer them reasonable alternatives to their views. I would consider how being accountable for my personal actions implies professionalism, so I would apologize to angry Twitter users for the way they feel.

As previously mentioned, I would not use Twitter as a platform to conduct this campaign. Its publicly open nature and inevitable spreadability is a dangerous field which encourages debate among users. Utilizing SnapChat or YouTube as a platform for this campaign would be more informative to demonstrate the care of killer whales. Instead of asking Twitter users what they want to know, it would be more useful to present pictures and live video footage. This ceases the potential of mass criticism to some degree and if both platforms were utilized SeaWorld would be applauded for their transmedia efforts. Having multiple touch points would be more informative and engaging whilst at the same time being less risky.

References

Arthur, W. (2016). Sea World Parks and entertainment ‘blackfish’ crisis. An assessment of ‘Blackfish’ effect on SeaWorld. Retrieved 23/05/17 from: http://csic.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/SeaWorld-Parks-Entertainment-Case-Study.pdf

Cassidy, E. (2017). Campaigns and Crisis Management. Social media, Self and Society. [Lecture Notes] Retrieved from: https://blackboard.qut.edu.au/webapps/blackboard/content/listContent.jsp?course_id=_133419_1&content_id=_6696662_1

Hurcombe, E. (2017). Investigating social news: emerging Journalism and news consumption cultures on social media platforms. Social media, Self and Society. [Lecture Notes]. Retrieved from: https://blackboard.qut.edu.au/webapps/blackboard/content/listContent.jsp?course_id=_133419_1&content_id=_6696662_1

Kietzmann, J. Hermkens, K. McCarthy, I. Silvestre, B. (2011). “Social Media? Get Serious! Understanding the Functional Building Blocks of Social Media.” Business Horizons 54.3: 241-251

Light, B. (2014). Disconnecting with Social Networking Sites. Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan

Lobosco, K. (2015) ‘Ask SeaWorld’ marketing campaign backfires. Retrieved 23/05/17 from: http://money.cnn.com/2015/03/27/news/companies/ask-seaworld-twitter/

Magnolia Pictures. (2013). Blackfish Official Trailer. [Video File]. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G93beiYiE74

Marwick, A. (2013). “Introduction.” In Status Update: Celebrity, Publicity and Branding in the Digital Age, 1-19. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Martinez, M. (2014). California bill would ban orca shows at SeaWorld. Retrieved 23/05/17 from: http://www.cnn.com/2014/03/07/us/california-bill-orca-killer-whaleseaworld/

Newsday (2015). SeaWorld’s #AskSeaWorld campaign backfires. [Image] Retrieved 25/05/17 from: http://www.newsday.com/news/nation/seaworld-s-askseaworld-twitter-campaign-backfires-1.10131989

Pemberton, B. (2015). ‘Are your tanks filled with orca tears?’ SeaWorld Twitter campaign backfires as marine park hashtag #AskSeaWorld is hijacked by animal rights campaigners. Retrieved 23/05/17 from: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/travel/travel_news/article-3019299/Are-tanks-filled-orca-tears-SeaWorld-Twitter-campaign-backfires-water-park-hashtag-AskSeaWorld-hijacked-animal-rights-campaigners.html

Sola, K. (2015). #AskSeaWorld campaign pretty much goes how you’d expect. Retrieved 23/05/17 from: http://www.huffingtonpost.com.au/entry/seaworld-twitter-fail_n_6950902

Tucciarone, A. (2016) Sea world’s social media campaign: epic fail. Retrieved 23/05/17 from: http://oustrategicsocialmedia.com/2016/02/16/seaworlds-social-media-campaign-epic-fail/#respond

0 notes

Text

Burberry and their social media transformation

Cara Delevinge and Kate Moss for Burberry (Akbareian, 2014)

Luxury brands have continuously battled with maintaining a high profit margin by providing innovative and quality products to their customers as well as retail strategies and marketing techniques (Jiyoung, Ko, 2010). However, the use of social media as a market communication tool has expanded to nearly all luxury fashion houses in the modern era and the likes of Facebook, Twitter and YouTube are now considered a necessity to thrive (Jiyoung, Ko, 2010). Luxury brands joined onto the social media frenzy later than other industries, whilst some use it minimally others have “become leaders, transforming the way in which different platforms are utilized” (Barry, 2016, p1). Most notably Burberry, the iconic traditional English luxury retailer, was the first luxury brand to exploit the potential of social media and utilize it to completely reshape their professional identity. This blog post will discuss how social media personalities have impacted Burberry campaigns, the dramatic transformation of target audience and how merging mass communication outlets has allowed the luxury brand to thrive.

Brooklyn Beckham photographing Burberry campaign (Lindig, 2016)

The professionals who are contained within the Burberry bubble have undoubtedly changed in nature in recent years. In 2016 Burberry employed 16 year old Brooklyn Beckham (shown above), the son of David Beckham, to photograph their most recent campaign (Hope, 2016). Beckham’s work was described as “boring” lacking any substantial talent and critics swiftly attacked Burberry for insulting well established professionals within the industry (Jones, 2016). The chief executive of Burberry, Christopher Bailey, has since implied that Beckham’s vast social media following and online popularity is why he was selected, despite his young age and lack of experience in the field (Hope, 2016). However, this high profile selection goes further beyond the models and photographers; even the backstage crews are handpicked in accordance to their social media fan base. Stylists, producers and makeup artists are only selected if they have adequate social media popularity (Hope, 2016). Consumers within the public sphere are attracted to these teams of social media fanatics because they believe they are engaging in some sort of high profile and private realm (Hope, 2016). Burberry openly admits it has “become as much a media content producer as a design company” (Hope, 2016, p1). Thus it would appear that conventional design values have been somewhat adjusted. This reflects upon the significant reshaping of not just Burberry’s professional identity, but the fashion industry as a whole.

The relationship between Burberry professional workers and their respective audiences has been remolded by the ever growing presence of social media. Burberry have succeeded in transforming a brand “for ‘chavs’ and English hooligans into a major trendsetter in social media marketing” (Phan et al, 2011, p214). In 2004 Burberry was particularly attractive to youthful English individuals characterized by impolite and anti-social behavior, otherwise known as ‘chavs’ (Phan et al, 2011). The extent of this problem, or jokingly named ‘chav attack,’ was so amplified that a group of hooligans who adopted the distinctive Burberry checked cap named the ‘Burberry Boys’ dominated Burberry’s image. Their association with uncultured working class consumers was embarrassing for the 160 year old swish designer label (Alexander, 2005). Brand revitalization was therefore pivotal to Burberry, so they consequently engaged in higher levels of involvement on multiple social media platforms. As previously mentioned, Burberry began to employ individuals with high social media profiles such as Kate Moss to represent and re-brand their image. Burberry regularly posted to the likes of Facebook, Twitter and YouTube and in 2009 even launched its very own social media platform called ‘The Art of the Trench’ where customers were encouraged to post pictures and stories of their iconic ‘trench coats’ (Phan et al, 2011). The brand grew from a “stodgy nonentity into a pioneer and major trendsetter” (Phan et al, 2011, p217) all through the use of social media. Social media enabled Burberry not only to entirely transform the relationship between clients and industry leaders, but also helped them to connect with valuable younger consumers (Phan et al, 2011).

The Burberry ‘Chav Attack’ (Pinterest, 2017)

Burberry’s brand re-imaging sparked a new wave of social media marketing which prompted them to merge mass communication outlets, thus enabling them to dominate markets. Burberry began to exploit the potential they saw of establishing online communities with consumers and connecting with a more widespread audience via social media. For the first time in the fashion world, Burberry live streamed one of their catwalk shows (link below) which received over 100 million impressions via Facebook and YouTube, and this marks their first major digital success story (Barry, 2016). Live streaming catwalks has since been considered a dramatic breakthrough in the fashion industry and key fashion houses have followed Burberry’s lead (Hope, 2016). This creation of participatory culture enables fans and potential buyers to interact with Burberry whilst not actually attending the show (Hifler, 2017). Furthermore, prior to ‘London Fashion Week 2015,’ Burberry debuted its most recent fashion campaign on the popular social media platform ‘Snapchat,’ which only lasted for 24 hours (Barry, 2016). This was dubbed as the first ever 24 hour fashion collection which was later praised as the “best piece of marketing in 2015” in UK’s marketing magazine (Barry, 2016). Burberry were also the first fashion retailer to launch their own channel on ‘Apple TV’ to enable customers to watch all of their catwalk shows live (Barry, 2016). The new option to live stream catwalks “turned runway shows into powerful consumer marketing events” (Wood, 2016, p1). Customers now had the ability to engage with catwalk shows, rather than being side-lined by industry leaders. Burberry is a prime example of how media convergence has enhanced their reputation and status as a high-end fashion retailer.

24 hour Snapchat Burberry campaign (Strugatz, 2015)

In conclusion, it is credible to argue that Burberry have successfully reshaped their professional identity via digital media on social platforms. Burberry’s introduction of live streaming runway shows transformed the fashion industry, and subsequently forced other players to increase their social media engagement. Burberry recognized early on the potential value that social media brings so they embraced the digital platforms and flourished (Tobias, 2013). However, Burberry have been subjected to recent criticism over their decisions on choosing high profile social net-workers such as Brooklyn Beckham to undertake work which clearly requires some level of professionalism. This is reflective of the industry as a whole, in which social media stars are now regarded as more suitable for high end jobs rather than experienced and qualified individuals. However, social media has enhanced Burberry’s perception within the public sphere by enabling them to shrug off the hooligan or ‘chav’ image, into a trend-setting, powerful and iconic brand. For these reasons, Burberry must be applauded and the crucial role that social media played must also be given some recognition. Burberry’s strategy of utilizing social media to its full potential enabled them to successfully re-position their image and enhance their own professional identity.

youtube

Burberry live streaming of London fashion week (Fashion Channel Milano, 2015)

References

Akbareian, E. (2014). Cara Delevinge and Kate Moss shot together for first time for Burberry. Accessed 31/03/17. http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/fashion/news/cara-delevingne-and-kate-moss-shot-together-for-the-first-time-for-burberry-9704045.html

Alexander, H. (2005). Burberry boss is happy with the chav cheques. Accessed 30/03/17. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1480169/Burberry-boss-is-happy-with-the-chav-cheques.html

Fashion Channel Milano (2015). “Burberry LIVE” London Fashion Week Spring Summer 2015. YouTube video. Accessed 29/03/17. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TOcyURw7Wc4

Hifler, L. (2017). Luxury brands and social: challenges and opportunities. Accessed 29/03/17. https://maximizesocialbusiness.com/luxury-brands-social-media-challenges-opportunities-18030/#

Hope, K. (2016). How social media is transforming the fashion industry. Accessed 30/03/17. http://www.bbc.com/news/business-35483480

Jiyoung, A. Ko, K. (2010) Impacts of Luxury Fashion Brand’s Social Media Marketing on Customer Relationship and Purchase Intention, Journal of Global Fashion Marketing, 1:3, 164-171, DOI: 10.1080/20932685.2010.10593068

Jones, J. (2016). Brooklyn Beckham’s Burberry campaign – the art critic’s verdict. Accessed 30/03/17. https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2016/jul/13/brooklyn-beckham-burberry-campaign-art-critics-verdict

Lindig, S. (2016). Brooklyn Beckham photographs his first campaign for Burberry. Accessed 31/03/16. http://www.harpersbazaar.com/fashion/designers/a13882/brooklyn-beckham-photographs-his-first-campaign-for-burberry/

Pinterest, (2017). Lots of chavs. Accessed 31/03/16. https://au.pinterest.com/derekshitbag/lots-of-chavs/

Phan, M. Thomas, R & Heine, K. (2011) Social Media and Luxury Brand Management: The Case of Burberry, Journal of Global Fashion Marketing, 2:4, 213-222, DOI: 10.1080/20932685.2011.10593099

Strugatz, R. (2015). Burberry, Mario Testino, tap into Snapchat. Accessed 31/03/16. http://wwd.com/fashion-news/fashion-scoops/burberry-mario-testino-tap-into-snapchat-10266512/

Tobias, K. (2013) Entrenched in the digital world. Accessed 29/03/17. http://www.businesstoday.in/magazine/lbs-case-study/burberry-social-media-initiative/story/191422.html

Wood, Z. (2016). From catwalk to checkout: how Burberry is trying to reinvent retail. Accessed 30/03/17. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/sep/24/burberry-reinvent-retail-from-catwalk-to-checkout-see-now-buy-now

0 notes

Video

youtube

A YouTube live stream of Burberry fashion show in London Fashion show 2015

0 notes