Digital sketchbook & blog-ish space for Asheville-based artist and educator Jack Michael.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Juror’s Statement, Lees-McRae College Student Art Show, Spring 2021

Last week, I had the pleasure of serving as juror for the annual Student Art Show at Lees-McRae College in Banner Elk, NC.

If you’re an art student or young artist and you’ve ever wondered what goes into a juror’s decision-making process for a show - whether it’s for basic inclusion in the show or for awards - please read on.

JUROR’S STATEMENT Lees-McRae Student Art Show, Spring 2021

Jurying a student show is a difficult task. Submitting to a student show is equally arduous, so first and foremost, I want to congratulate everyone for having the courage to submit your work.

By nature, the jury process is neither kind nor an exact science. Evaluating artwork is, in many ways, a subjective exercise mediated by personal taste. But it is also a skill honed by experience, research, and by regularly considering artwork from ancient eras to the present day. As an artist and educator, I’m old enough to have developed a time-tested approach to evaluating craftsmanship, aesthetic quality, and cultural thoughtfulness. However, I’m still young enough to remember the undergrad-era sting of having my work – which I (wrongly) felt had singular vision and emotional importance – overlooked for awards and inclusion in shows. I remember asking myself “Why me?”, not knowing then what I know now: that a juried show is not only about the artwork; it is a relational exercise between artists, artwork, and the juror.

Ideally, a juror’s initial decision – the making of “the first cut” - is based on a combination of objective factors such as craftsmanship, presentation, technical skill, and attention to composition. If these are lacking in an artwork, then the work cannot hope to be a vehicle for greater meaning. At best, artwork with a dearth of craftsmanship and skill is mere decoration; at worst, it is a weak monument to an artist’s inability (or unwillingness) to commit their time and energy to their own ideas and personal potential. Young artists often struggle with this truth, making halfheartedly-crafted work that bounces around between mediums and themes, never pausing long enough to develop the technical expertise necessary to be a truly good artist. In the great quest to know what their work is “about” and how to make it, art students often make the mistake of looking for an idea that is “worth believing in” or seeking a new process – usually a novelty-based one that they feel is unique - before they really believe in and commit to their work. To those young artists, I say this: you think that commitment to your work is an elusive feeling that will finally grace you if you find some idea/process worth believing in…but you have it backwards. Belief does not pave the way for commitment; if you wholly commit to your work in both idea and process, you will create things worth believing in.

Aside from attention to craft and technical skill, it is this commitment to ideas and methods that guided me in making “the second cut” to select the award winners for this show. Ultimately, I was looking for artworks that answered “yes” to the following questions:

Does this artwork successfully convey a mood or message without being trite or didactic?

Aside from basic technical proficiency, does the work evince a developed sensitivity of material handling?

Does the work go beyond mere observation/decorative quality to compel the viewer with a question or deeper attention to an idea? Does it invite me to explore it further?

Does the work successfully avoid cliché?

Has the artist pushed boundaries, broken rules, taken risks, or at least tweaked the conventions of this medium’s typical subject matter?

Does the work resonate with me in some way, either stylistically or ideologically?

Is the work creative, free from derivation, and in possession of a sense of inventiveness and original thinking?

Does the artist un-self-consciously embrace a style that is markedly his/her/their own?

Would I like to see more work by this artist?

Is there a harmonious marriage of form, subject matter, and content?

Does the piece exhibit the potential to grow into a broader, more mature body of work that seeds new, kindred artworks in the future?

Does the work take an unapologetic critical or investigative stance in relation to a specific idea of contemporary relevance, or at least to our culture at large?

And Does the combination of ideological specificity, emotional vulnerability, and attention to craft & content indicate that this young artist might on the verge of truly committing to addressing the ideas in this work for the sustained near future (the next 1-3 years)?

I want to emphasize that every submission I reviewed had positive attributes; there were several of solid merit that did not receive an award. There were also many works that answered “yes” to some of these questions, but fell short of award due to craft, presentation, or technical issues. There were just as many works that displayed adept material handling but fell prey to cliché or to being mere observational decoration. To those of you who did not receive an award: please continue (or start) to believe in your ideas and commit to technical expertise and attention to craft. If you do, good things will happen.

To those of you who did receive an award: I wholeheartedly congratulate you! I, as your humble juror, did not give you an award – you earned it.

Ultimately, the pieces selected for award in this show (some to a greater extent than others) positively addressed the above questions in a way that marked them out from the crowd while also evincing technical proficiency and attention to craft. Even in the case of top awardees, however, the aforementioned questions should be embraced as consistent guidons to propel further improvement. I encourage you to copy these questions out and keep them in a place where they will confront you every day (whether you like it or not). Look at them, strive toward them, and internalize them until your own work resoundingly and consistently answers “yes” to each and every one. There is always, always, always room for improvement. People in other professions may have the luxury of someday “arriving” at penultimate expertise but as artists, the only thing we can get comfortable with is the fact that we will never “arrive” – we will (if we are smart and lucky) always be seeking, evolving, pursuing.

I encourage all of you – awardees and others alike - to continue to submit your work to shows such as this one, and to juried shows and calls for proposals or residencies on a regional and national scale. Exposure to the judgments of a wide variety of arts professionals (in addition to your stellar faculty) is the most valuable and surefire way of challenging and maturing your own ideas and skills. This is true even – and perhaps especially – when things don’t go your way.

Above all, I hope that all participants of this show remember this: thick skin is important. As an artist at any stage in your career, many of your best efforts will result in disappointment, but the number of disappointments is a downward-trending arc over time: the longer you do this wholeheartedly, the more sublime, elating wins you will achieve. Rejections are not a reason to quit; they are reasons to lean in and commit to your ideas, skill development, and professional growth sooner rather than later…or get out of the way of those who are doing that and find the path of expertise and interest that is truly for you. As a student artist, if you are successful at only 10% of your pursuits, you are doing well. So cultivate patience, perseverance, skill, and a thick skin. Happiness isn’t a function of chance – it is the result of ideological commitment and technical expertise exercised over time, resulting in somewhat-consistent success. Start today.

Finally, I want to thank Lees-McRae College and the Art Department for your genuine hospitality and for the invitation to jury this show – it was truly an honor. I see deep promise in a healthy selection of this work. That is no doubt due to the Art faculty doing the energetic, dedicated, and often emotionally-taxing work of molding young people with ideas and feelings into young artists with mature ideas, considered feelings, and – above all – work that expertly carries the resultant messages and investigations. Thank you for your service to the future of art and artists in our region and beyond, and thank you again for having me.

Warmly,

Jack Michael Art Instructor, Blue Ridge Community College

#art#artist#artists#artstudent#artwork#gallery#exhibit#kunst#artschool#makeart#makeartdaily#illustration#painting#drawing#design#photography#sculpture

1 note

·

View note

Text

Achievement Unlocked: I finally updated my website + portfolios.

What’s the thing that every artist dreads, besides a good ol’ rejection letter?

Updating their website, of course.

I’ve been putting it off for six months, but it’s finally done! New features include: a portfolio page for digital and editorial illustration, a portfolio page for artist book forms, an updated CV, and (of course) a link to this Tumblr.

Scope these screenshots:

You can check out the full site at jackmichael.art. Enjoy!

0 notes

Text

PRAWCESS for creating “Flag for the Society of Mystics”

A student recently asked me about my "prawcess” (Appalachian for “process”) of creating flags for the Associated States of Neocadia. I sometimes forget that the youngsters don’t have their own patterns and rituals for engaging with work yet. Here’s what I told him & showed him:

It goes a little something like this.

1) An event in the real world (as opposed to the Associated States of Neocadia) spurs me to have an idea for a new flag. This event is usually connected to global news and politics, education, or a local event related to farming, protest, etc.

2) I write down some thoughts in stream-of-consciousness style before the feeling leaves me. They don’t have to be sentences or even phrases. Just words are fine.

3) I ponder on that writing for a few days before deciding what the name of the flag should be. The name always comes first. After the name, I write a sort of short mythology or mission statement that explains the event, concept, or institution that the flag will represent.

4) From that statement, I begin to gather visual research and make initial pencil, pen, and watercolor sketches toward the design of the flag.

5) Finally, after the initial sketches seem worth fleshing out, I map out the flag in Adobe Draw and Adobe Illustrator. This lets me create layers of elements that I can move (and remove) as I progress in my design. I tend to begin as a maximalist and end with something more Modernist. I wouldn’t be able to do this as fluidly on paper; working in the digital space gives me power and speed.

Here’s the initial digital design for Flag for the Society of Mystics.

After putting away the digital design for 3-7 days, I return to it, and begin to make edits - usually by removing things.

Here’s that same design, whittled down to its most essential elements.

After I’m satisfied with the digital design, I make final decisions re: color palette, and then use my constrained chosen color palette of linen fabric to make a maquette. My maquettes are typically around 15″ x 11″.

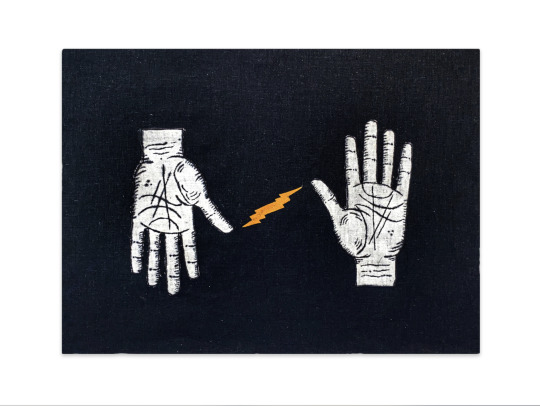

Here’s the Flag for the Society of Mystics maquette.

Seeing the maquette in real (albeit tiny) life lets me understand how my cloth, painted/printed elements, color, and proportions will interact with each other. If I want to make changes, I don’t necessarily make a second maquette - I typically just make notes of what to change, do the math to scale elements up or down, and move on to my full-sized finished piece.

Here’s the finished work, Flag for the Society of Mystics.

This beauty is 52″ x 36″, and is made from linen cloth with appliqué, hand-painted fabric dye, machine stitching, and hand stitching.

Every artist’s process is different, and I’m intensely interested in how we all work. That’s part of the reason that I love studio visits and sketchbooks so much. If you have any good recommendations for where to see in-depth studio visits or cool sketchbooks, please share. Thank you!

0 notes

Photo

I’m scheming up my next Lesson Flag of the New Republic. This one was made over a year ago; the other side says “OWN LESS / DO MORE”. I’ve been focused on linen flags representing different organizations and holidays of Neocadia since September 2019. I’ll be working on those for dozens more years, I’m sure, but in the meantime the lesson flags and prints should continue.

So...what should be my next message? How about: “DON’T JUST / ACT WOKE ACTUALLY WAKE UP”

? :D

0 notes

Photo

One of my favorite illustrations from one of my favorite contemporary illustrators, Carissa Kaye Powell.

0 notes

Text

INTERVIEW FOR TEACHING PRINT ONLINE + MOMENTS OF RADICAL VULNERABILITY

In the wake of COVID-19, printmaking professors have been faced with a special challenge of taking printmaking instruction online. Printmaking is a famously community-oriented activity, not least of all because presses - the heart of our practice - are fucking expensive, and gathering closely around one is integral to artmaking for most of us. In the age of social distancing, communing over the press bed simply isn’t possible. Many printmakers don’t have access to a press since shelter-in-place orders took effect. (I am VERY grateful and lucky to have a press at home thanks to Steve Robinson of Letterpreservation and Vandercook.info, a true American hero of printmaking.)

Across the country, innovative instructors have assigned their students a nifty task: interview a practicing printmaker about their education, history, and current practice. I’ve been lucky enough to be interviewed by several students from across the country in recent weeks. The process has been both humbling and enlightening. I’m sharing some of the questions they’ve asked me and my answers to them in hopes that they might help you on your own journey to being the best possible version of yourself as an artist (these questions go WAY beyond printmaking).

Prepare for some radical vulnerability, professional practices insight, and weird revelations that just might help solve some of your own studio challenges!

Spoiler: I saved the most important question + answer for last.

Q: What was your art education experience like and what is your background? A: My art education experience was about as distant from printmaking as it could have been. I attended a rural high school that had a great art department, but that department focused largely on technical instruction in drawing, ceramics, and photography. Conceptual work strictly was not discussed (a huge detriment to pre-college students, in my humble opinion).

When I attended undergrad (at Sewanee: The University of the South), I enjoyed an outstanding art faculty and a lovely art building, but there was no printmaking facility and no one who had experience teaching printmaking. I focused on photography and sculpture while I was there, and also took bookmaking courses. One of my photography classes was in alternative processes, including platinum palladium photography. While that is technically a type of printmaking (if you consider the negative to be a matrix used for contact printing), that was the extent of my print-related education. However, after practicing as an artist for four years after undergrad I moved to NYC and took an intern position at Gowanus Print Lab/Park Slope Press. Gowanus Print Lab is a community print space near the eponymous canal, and the partner business (Park Slope Press) specializes in letterpress and silkscreen operations for the wedding and event industries. I had never worked in printmaking, and they primarily hired me for my professional experience in managing social media and digital communications. Two weeks after I started, my boss quit with no notice. The owner of the company (whom I had only met for about two minutes) asked me if I had the experience to step up and run letterpress and screenprinting operations for Park Slope Press, including both design and print duties. I DIDN’T have enough experience, but I said yes anyway, and thus began my very steep learning curve in printmaking. It all worked out, though, and the company owner ended up being a great friend that taught me a lot. I enjoyed a solid experience with GPL/PSP, and also worked on occasion as a stand-in contract printer for a few other shops, artists, and editions houses in NYC when a big job needed doing. I continued my work as a contract printer when I moved to Atlanta, where I worked as a flatstock specialist with Danger Press. That position included everything from Pantone matching ink to trimming paper to printing posters for companies like Adult Swim, Google, and Coca-Cola. Even though I came for the flatstock, I also ended up printing tshirts, which has its own charm. I loved that job so much, and still maintain cordial contact with those folks. Ed Jewell is still the best boss I’ve ever had. I left to open an art gallery dedicated to works on paper and to pursue grad school (both of which were critical for my career and life). Even though I’m grateful to have an MFA (forthcoming in about a month, anyway), a part of me still misses being an inkslinger-for-hire…the time I spent in editions shops was as rigorous an art education as any MFA program, and in some ways even stronger.

Q: Is art your only career or do you support yourself by doing other things in addition to art? A: Art is not my only career…at least not EXACTLY. In addition to selling my work and still doing the occasional contract printing, I also teach a combination of college courses and private workshops. The private workshops pay better per hour than both contract printing and adjunct positions with colleges, but the income is less steady than working in higher education. I’m also a sponsored adventure motorcyclist, but that income is mostly in gear rather than in direct cash. Being an ADV rider isn’t totally separate from my art practice, though. I’m the inventor of a fictional republic called the Associated States of Neocadia, and one of the elite societies in this fictive world is the Guardians of Neocadia. Those folks are good samaritans who patrol the ASN by motorcycle and monitor the health and wellbeing of forests, farmland, roads, waterways, and animals. They report back to the GoN headquarters by mail, offering their latitude/longitude and detailed observations on the natural environment. As you might imagine, this provides RIPE opportunities for print and drawing/painting related practices, as well as motorcycle-based endurance performance. So, I hope bring the Guardians of Neocadia to life in the REAL world through a combination of motorcycle-based work and print-based work as soon as the COVID-19 situation settles down. I’d planned the inaugural trip for the Guardians of Neocadia to begin on June 1 and go from the southernmost point of the continental US (Key West, Florida) to the northernmost point of the US (Deadhorse, Alaska), but sadly the Canadian border is closed and it’s simply unsafe to travel. But when the border opens back up, I’ll be off!

Q: What do you want to say with your art? A: My art explores the dynamics of utopian longing, ambition, and failure. Right now, I’m using flags as a visual portmanteau to talk about how we all have very idiosyncratic ideas about what qualifies as “utopian”, how we all experience utopian yearning, and how those ideals are unattainable in large part because highly personal ideas typically fail (at least to some extent) when they attempt to transcend into the shared environment of the real world. I don’t know if I’m really trying to say anything so much as I’m creating fictive models for testing my own ideals in the real world, and trying to bring my own utopian longing to life in a way that doesn’t squash the agency of others. I’m also attempting to mend (but not erase or rewrite) my own history using art as an ongoing recuperative practice. I’ll be uploading my unabridged master’s thesis to my website when I submit it to Georgia State University later this month, so feel free to peruse it in all of its 50+ page glory!

Q: How do you feel about getting political with your art ? A: I’m very comfortable being political with my art. I would say that politics is a strong basis for my work, along with autobiography, history, and literary fiction. That said, I think it’s important to for every person to draw their own line regarding where art stops and activism begins, and decide where they want to be in relation to that line. There is no wrong answer. It’s just important to be intellectually honest about where art ends and propaganda begins. I personally engage in both, but I keep them separate (there is a brackish place where one informs the other, but they are definitely separate). Art poses questions and propaganda foists answers. And propaganda isn’t (or shouldn’t be) a dirty word, but its aims are different than those of art, at least good art (in my humble opinion). Even if your art is politically engaged, it doesn’t have to hit people over the head with didacticism the way that activist visual materials do. That’s the job of activist material - but it is not the job of art.

Q: What or who has influenced you in your practice? A: My practice is more influenced by studies of literary fiction, US history, and politics since 1900 than it is by other art or artists. Things that stand out are Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography; the writings of Wendell Berry; Thomas More’s Utopia; German fairy tales; the history of the Civil War and the Industrial Revolution; environmental activism; cultural studies of the American South; and labor movements.

However, if I had to name a few artists that have helped light my way, they would be: the late Henry Darger; Dan Levenson (contemporary); the late Ree Morton; Amy Pleasant (contemporary); Bean Gilsdorf (contemporary); and Hans Haacke (contemporary). Likewise, my professors at Georgia State University (most notably Craig Drennen, Craig Dongoski, Jess Jones, Nicole Benner, and Susan Richmond) have been instrumental to my work where professional practices, technique, and critical theory are concerned. I truly wouldn’t be where I am without my current MFA thesis committee and a handful of other superstars on the faculty there.

Q: How do you seek out opportunities ? A: I seek out opportunities in the usual places: Open Call Café, CAA, my state art council’s website, and through friends and mentors. However, I cannot stress enough the importance of staying involved in academia for a constant stream of opportunity. Once you’re no longer part of that college community, it’s up to you to maintain very close connections with people through self-organized collectives and professional organizations if you don’t want to become one of those people that goes two years without a group show and five without a solo show. Momentum is real – don’t lose it. If people forget your name, it’s the beginning of the end.

Q: How do you market yourself and build a collector base? A: I market myself through Instagram and the workshops and college classes that I teach, but I would hardly call it “marketing”. Marketing isn’t a dirty word, and honestly I wish I was better at it…but I just don’t enjoy it. I want to make work, not talk about making work to strangers who only MIGHT support me. Still, it’s a necessary evil, and I’m still working out how to put in minimal marketing effort so I can spend maximum time in the studio. I don’t have a collector base YET – keyword YET – but in the grand scheme of things I’m pretty young (32), and still growing my career and my audience. You’ll also find out for yourself that it’s a little harder to build a collector base as a printmaker. There’s a perception that prints are less valuable, so while you may have more sales initially, it’s hard to build a career that’s based on fame in the secondary market because your work isn’t perceived as being valuable enough for resale (unless you’re Chuck Close, Leonardo Drew, Julie Mehretu, etc….but you’ll notice that all of those folks are painters or sculptors FIRST and printmakers only by INCIDENT and usually only with the help of Crown Point Press, etc.). I’m trying to find a niche way around this by combining my printmaking with textile work and painting in a way that produces unique works that can be more perceived as paintings or sculptures, and ergo gain me more traction in the secondary market and more money in primary sales from the studio.

Also, if you want to have a career as an artist rather than just as a printmaker, it’s also important to NOT become one of those printmakers that is technique-obsessed and eschews a solid conceptual framework in favor of perfecting bellybutton-lint aquatint or some other absurdly specific “new” technique (read: dry riff on an established technique). Those folks – even though they would scorn the statement – become relegated to being famous in the print world and nowhere else. They live for SGCI, but only other printmakers know their name. That’s all well and fine if you only aspire to a career in academia and you’re lucky enough to get one. But for the rest of us who aspire to more, you MUST live outside of the world of print as well as in it. You can’t count on a job in academia. You can’t count on selling enough prints in some local members-only gallery to make ends meet. Hell, none of us can count on being an artist as a way to make a living.

But if you want certain death-by-tiredness for your career, and you want to rest on your laurels and NOT build a collector base, by all means go ahead and focus on making pretty, meaningless monotypes or abstract bellybutton lint aquatints.

I can hear the pitchforks being sharpened now, ha!

Q: How do you price your work? A: Here’s my work-pricing formula: ($ spent on materials x 2) + (number of hours spent on edition x my hourly rate), divided by the number of prints in the edition. I then factor in how much it takes me to package and/or ship a print if packing and/or shipping is requested.

I calculate how much I spend on materials down to the very gram of ink and modifier used – nothing goes uncounted. I use an affordable digital kitchen scale for measurements, and I keep very precise ink recipes and records about paper usage, room temperature and humidity, and where I sourced my copper, etc. for EVERY edition in case I need to exactly repeat the edition. All of this is especially critical when working for a client, and I am always surprised and disappointed when these skills aren’t taught and enforced from Day One in Introduction to Printmaking courses. If you don’t start to build those professional expectations for students early on, your program will churn out passionate printmakers who have skill at the press but are useless in the grander scheme of the studio. They will be lucky to sell enough prints on Etsy to float their art practice.

Anyway, back to pricing: for instance, let’s say I spend $100 on ink, modifiers, paper, etc. for an edition. I also spend 30 hours between illustration, etching/carving/exposing a plate/block/screen, and printing an edition of 20 prints. My hourly rate is $50/hour. That’s $200 in materials charges + $1500 for my time, divided by 20 prints, so each print is $85. If I’m selling the print unframed in a gallery, it will typically be in a glassine or paper sleeve (I’m trying to get away from plastic) with a piece of rigid matboard enclosed for safety against bending. The total cost of that material is typically between $1 - $2.50, so I add that to the cost of the print. If I’m shipping the print, the cost of the mailer and shipping fee is also tacked on.

Q: How has your practice changed over time/in what ways has your career developed over time? A: My practice has shifted from commercially-motivated work to a more fine-art focus, especially since I joined the GSU MFA program back in 2017. Even though I do still engage in commercial work, I mostly only do it when I need to rack up some savings for a new piece of equipment, a big trip, etc. It’s not that I don’t think a printmaker can live in both of these worlds – we can – but where we spend our time is where we’ll garner more expertise, work, and acclaim. For me, I want that to be in a fine art setting rather than slinging ink in a commercial shop. I think that folks who work in editions presses like Crown Point Press get the best of both worlds here.

If I had my dream job, it would be working in a college that invited artists in residence on a semesterly basis, and I would have a position teaching one or two print classes each semester and assisting the visiting artist with producing an edition of prints in tandem with a show at a local museum or gallery. Alternately, doing master printing for a museum alongside contemporary artists that show there would be great, but I would really miss the environment of a thriving college. The former scenario would give me my ideal blend of teaching (I love working with students!), producing a limited amount of professional editions, and having time to make my own work. That last part is key. That all would make for a VERY sweet spot that I would love to see as the eventual evolution of my practice.

Q: What do few of your audience members understand in your artwork? A: I think my current work is still unfolding to my audience. I’m still learning who my audience is, too. Up until quite recently, my work used to be explicitly about trash as a vehicle to talk about classism, abundance, economics, and environmental issues. Before that, my work was all over the place: enviro-political work on the Mexican border; work that criticized social media; abstract work that used weaving and monochromatic painting to explore systems of power, especially where gender was concerned. In the last year, though, I’ve been rigorously researching the influences and processes of my work, and I’ve found that all of my work – even from undergrad, over a decade ago – points to discussions of utopia. More specifically, of what I consider to be utopic, how and why utopian yearning motivates human existence, and how utopian longing so often fails.

I think that most folks don’t understand this about my work yet – but it is a relatively new development. All of the work I’ve ever made has come from a place of nostalgia for a rural life that works in harmony the earth, and where people cultivate genuine connections with a family group (both blood kin and chosen family). The work likewise comes from a position of feeling like my ideas, preferences, and beliefs would make the world the best possible version of itself if only I could will my vision into existence. Does this sound narcissistic? Sure, maybe. But doesn’t everyone who crusades for any cause feel this way, at least a little? Doesn’t anyone who believes in ANYTHING (large or small) feel this way to some extent, even if they don’t realize it? Every action we take, from microcosmic choices like which shampoo we buy all the way up to who we vote for and what we do for a living are ALL choices that are informed by what we deem to be utopic. It’s subconscious, but it is there. Every action is a small arrow flying hopefully toward a noble, personally magnetic target on the horizon. But like a horizon, we can always see utopia and always chase it...but can never quite get there. Nonetheless, we try. I think we have to try. What else is there?

Q: What do you struggle with most as an artist? A: I used to struggle with commitment to my work, because I could never decide what my work was really about…but in my next answer you’ll see the resolution to that.

It’s hard to admit, but I’d say my #1 hurdle is jealousy. Or maybe I should call it consistent self-esteem? Maybe they’re sides of the same coin? Either way, I’m constantly comparing myself to others and coming up with bad results.

If I see that one of my peers has been nominated for an award, I simultaneously think “Gosh, I deserved that too!” in a moment of delusionally high self-esteem. In the same moment, I think “Ugh, my worthlessness and unoriginality has been verified. I am a loser. Why does everyone tell me I have a bright future ahead of me and then not nominate me for something/accept me to a residency/put me in a show?” This kind of thinking is toxic, but it’s hard to overcome in the moment. I’m still trying to nail down a daily practice that helps me proactively overcome the jealousy/insufficiency monster.

It’s been especially hard in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. On the one hand, I am very fortunate to have an incredibly supportive spouse whose job hasn’t been completely financially tanked by social distancing (he’s a health worker, and I truly salute his bravery every day). He gives me the real talk about how ridiculous I’m being when I say things like, “There goes my art career”; I cannot count the number of metaphorical ledges he’s talked me off of. I also have a small but dedicated home studio space and an intaglio press that I am so very grateful for, especially as an introvert and printmaker in a quarantine. I have art supplies. We have a lovely home on an abundant acre where we can sequester ourselves and grow food and raise chickens. And most importantly, we have our health and each other.

On the other hand, I can’t help but look at all the artists who were already established with galleries and teaching positions before the pandemic and think, “Ugh, why me? There goes my career. I was on such a great trajectory before COVID-19. But my MFA thesis show was canceled. My residencies that I got accepted to were canceled. I moved to Asheville - a famously insular art scene - hoping to make meaningful connections in the art community, and now I can’t meet anyone. Will schools even be hiring adjuncts for the fall? Probably not. I’ll be unemployed and working in obscurity forever. I deserve this. All my stellar teaching reviews don’t mean a thing - I’m a mediocre teacher, and my artwork was never going to be important anyway.” Again, this way of thinking is toxic. It defies logic in favor of emotion and forgets history in favor of the moment. We’re all suffering right now. And my hunch tells me that the jealousy/insufficiency feelings I was having before COVID-19 (and really, for my whole life) are NOT unique amongst my peers. When your whole life’s work is based on constantly pouring your belief and self into work that is made LITERALLY to be critically reviewed and discussed, loved or hated (or worse, ignored), how could we not feel this way? We don’t often talk about these ugly feelings, but I think we should. Maybe we’d all feel a little less mercurial and a lot less lonely.

And the final and most important question and answer:

Q: How did you solidify your practice and the way you work? (This interviewer felt like her practice was all over the place and that she didn’t have a solid style or conceptual approach to her work. This is without a doubt the No. 1 question I get from ALL of my own students and from students at institutions where I give lectures and workshops.) A: The way I solidified my practice was a very conscious decision to choose what Jerry Saltz calls a “creative mechanism”. I used to struggle with commitment to my work, because I could never decide what my work was really about, or what it would look like. That all changed last summer.

I was sharing a meal with one of my professors (Craig Dongoski) at a residency in Greece, and I was bitching about not knowing what my work was about (at least this is how I remember it…and it’s highly likely – I used to constantly whine about this). He looked at me and he said, “You know what your problem is? You can’t COMMIT.” He picked up a piece of plastic wrap covered in olive oil and shook it in my face and said, “Do you see this piece of plastic wrap? You could make genuinely interesting work about this piece of plastic wrap for SEVEN YEARS if you would just commit to it. Your problem is that you think commitment comes from belief – but you’ve got it backwards. It’s the other way around: belief comes from commitment. If you commit to something, truly commit to it and refuse to abandon it, that work will yield something worth believing in.”

After I came home from Greece I had a really outstanding session at the Hambidge Center for the Arts & Sciences (possibly the best residency of all time), and I finally found (created, COMMITTED TO) a creative mechanism. First, I spent a solid week of 16-hour days rereading every sketchbook I had since undergrad, especially the ones from the past five years. I made a word cloud of words that I thought might be related to what my work was “about”, and then I transcribed my sketchbooks into a single Google doc and did in-document word searches for those words to see how many times they had occurred across the years. I wrote the top ten words onto pieces of paper and tacked them up on the wall and connected some of them with string, like a crazy detective trying to solve a murder. Those words were: politics, community, utopian, failure, history, modernism, nationalism, manifesto, nature, & home. The word that had the third-highest instance of occurrence was “utopian”, but it was the word that had the MOST other words connected to it by string. Thus, it became my central topic…what my work is “about”, so to speak. It is the topic I decided to commit to.

But I wasn’t done. The topic is not enough. You have to have a reason, an investigation, a question. I decided that my reason was to study the dynamics of utopian yearning: why we want what we want, how utopian ideals cause friction, why utopias fail, and why we keep yearning for them anyway. For several reasons, I’ve decided to dedicate my life to this question.

Once I had my topic and reason, I decided on a creative mechanism – what Saltz calls a “conceptual approach” - and what I think of as a very specific structure or set of rules that can guide my work, making my output recognizable even across the multiple media I work in. The first part of this literally happened in the course of a few days, but it has evolved, expanded, retracted, and has now reached a comfortable place. When I was at Hambidge, I took what my professor told me in Greece to heart: after my research and word clouds, etc., I chose a ridiculously specific thing as a visual portmanteau to talk about my topic and reason (utopia & studying the dynamics of utopian yearning). I chose flags.

Why flags? 1) They’re relevant to my personal history. I was a cadet in JROTC, I come from a military family, and flags and other nationalist regalia are very relevant to my sociopolitical history. 2) Flags are very relevant to my current concerns regarding utopia and failed utopian yearning. I think that America is failing as a country due to rampant nationalism and conflicting ideals of what constitutes utopia. 3) I really, really, REALLY enjoy sewing and drawing and printing and painting flags. They are spaces of infinite symbolic possibility, and I can load them up with whatever colors and imagery I want. The form of a flag allows me to work across media, which keeps me from getting bored. It’s very important to choose a creative mechanism that is relevant to YOUR PERSONHOOD, relevant to YOUR TOPIC/REASON, and that you CAN ENJOY ENGAGING WITH FOR A VERY LONG TIME. If any one of these things is missing, you won’t be able to maintain your joy in committing to this work, or it will seem hollow to your audience because it is hollow to you.

I knew that I could make work about utopian yearning using the creative mechanism of flags for a VERY long time. However, after I brought this work back to GSU at the end of the summer, my mentors and faculty helped me to expand and solidify an even more solid and abundant creative mechanism: the Associated States of Neocadia, and The Manual for Neocadia. This fictive country that I invented is loosely based on the United States, and even though the goings-on of Neocadia are set in an ambiguous time, the work unfolds very much in reaction to what’s happening in the world around us. The purpose of the ASN is twofold: first, it’s a place where I can exercise agency to make a world in my own image, thereby “solving” the problems I see in our current world and studying the dynamics of my own idiosyncratic utopian longing in the process. Second, it’s a protected space where I can try to resolve (but not rewrite or erase) issues in my own past. The work I make in the service of fleshing out Neocadia is an ongoing recuperative practice for me, and also a way to study how utopia inspires yearning, ambition, work, failure, anguish, hope, and continued longing.

The Manual for Neocadia is a refining gesture of the larger creative mechanism of the ASN. It is a highly detailed manual for existing in the ASN, and it is evolving over time. I’m currently working on Chapter 1 (Manifesto of Neocadia) and Chapter 2 (Visual Lexicon of Vexillology). Vexillology is the study of flags; so you can see that my commitment to flags as a creative mechanism expanded up a LOT to include an entire fictional republic, and then honed itself back down to the concept of a citizens’ manual. I consider all of my artworks to be pages in this manual, which I eventually hope to publish as a massive book or series of smaller volumes (encyclopedia-style).

So now that I have this creative mechanism (Associated States of Neocadia > The Manual for Neocadia > flags > utopian yearning), I don’t struggle with commitment, nor with belief. And because I’ve genuinely committed to my work and I truly believe in it, I don’t struggle finding motivation to go to the studio – which used to be my biggest hurdle. I was afraid to work, because I felt like a fraud. Every hour held the potential for a failed experiment or a depressing realization that I had no idea what I was doing or what my work was about. But now I wake up every morning with a mission in my blood. I have problems to solve. I have a world to build. I have flags to make. I have failure to grapple with and eventually forgive. I have utopian longing of my own to enact and see what happens.

It’s all reliant on radical vulnerability and intellectual honesty, and of course on the work.

Without work, there is nothing.

0 notes

Photo

It’s Decorative Gourd Season, Motherfuckers (more)

6K notes

·

View notes