Text

“Map”

We cannot conceive the topographical project of globalization without discussing individual experience. Yet, the presentation of individuality can rely far too much on a totalizing voice, creating a distinct problem for an author. All human beings are rooted within a singular perspective, able to identify the needs, interests and experiences of others as best as possible from the naturally limited vantage point of our own subjectivity. In what ways is it possible to deconstruct the way in which global capitalism dehumanizes specific subjects without engaging in an act of mimesis? How can creative work avoid replicating hegemonic structures on a more intimate scale while still offering a variety of subjects all effected differently by the same force? Within its sprawling yet intensely intimate narrative, Tropic of Orange appears to respond to these questions.

Reorganizing the “grid” of Los Angeles, Yamashita’s novel attempts to de-center the hegemonic constructions of globalist discourse without mimicking the all-consuming nature of such structures. The novel’s topography as a whole is constructed through the interactions between different character’s perspectives. Within each character’s narrative, the novel uses a wide variety of styles in an effort to present individual identity while calling attention to the fantastical nature of authorship and storytelling. Through this process, Yamashita’s topography is both concerned with distinct places and people as well as the broader function of space-time compression as a product of globalization. The global grid is simultaneously malleable and rigid, continually constructed and deconstructed through Yamashita’s authorial voice.

I have chosen to represent a combination of ideas through the attached photo of a set up for a game of “mikado spiel” or “pick-up sticks”. As a conceptual topography, the sticks represent formally a series of intersections created by a combination of chance and deliberation. The sticks are designed to be cast in a certain manner, the more crossing of individual sticks the better, but their specific placement is still random. On another level, this image is a meeting point between different “players” of the same game. They both present and encourage connection. This image highlights certain aspects of how Yamashita’s text functions as a whole. Upon each turn, players of this game must assess how their manipulation of an individual “mikado spiel” will affect the larger pile. In a similar way, we as readers are encouraged to think about how our discussions of specific characters affect the broader purpose of the novel. Yamashita marks difference within each character’s narrative through different stylistic choices, yet the novel as a whole is concerned with a more macro level understanding of how these separate stories connect.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reflection

“West Africa’s contribution to the African diaspora lies not merely in specific ritual symbols and forms, but also in the interpretive practices that generate their meanings.” Apter 180

“As I will argue throughout this book, as discursive objects, ‘origins’ are fundamentally emergent in nature and can be studied ethnographically as they arise.” Palmie 46

These two quotes represent a dialectic between two different ethnographic understandings of religious practices connected to the African diaspora. The first, from Andrew Apter, demonstrates what is often termed an “Afro-centric” understanding of diasporic practice. Apter believes that ethnographers cannot deny the connection between new world religious practices and their African “counterparts”. He argues that beyond just simple linguistic and practical similarities, religions of the African diaspora have retained a central interpretive framework that originated in West African communities. Stephan Palmie falls on the opposite side of this debate, viewing such religious systems as syncretic amalgamations of different cultural influences. He argues that to treat Africa as the sole point of origin for a religion like Santeria emulates a long history of cultural colonialism and that Santeria must be understood according to how it has been shaped by various contextual factors.

This dialectic is complicated for a variety of reasons. As Palmie concedes, his ideas are made problematic by the way in which several movements started by practitioners within the Americas have taken an Afro-centric perspective as the basis for constructing a cultural origin. Apter’s ideas are also difficult to deem wholly credible as they are similar to the extremely racist ideas of anthropologist Melville J. Herskovitz and conflict with how many diasporic communities would define their own origins. Herskovitz’s stance has plagued scholars like Apter since it was popularized in the 1950s. He was the first to argue that scholars need to recognize a connection between religions like Santeria and West African religious practices, using that to discuss broad “cultural carryovers” all of which related to a deeply racist perspective. In their different stances, Palmie and Apter demonstrate an incredibly complex globalist discourse about the applicability and purpose of the cultural origins.

Within this ethnographic debate lies a central tension expressed within Stuart Hall’s essay “Cultural Identity and Diaspora”. Hall’s central idea, that one both cannot outright dismiss nationalism and must reckon with the fact that diasporic identity is related to an semi-fluid process of internal and external definition, does not seem to be present in this debate. Within the discourse between Palmie and Apter, one can see one of the most important functions of globalization: the intense awareness of definitions or cultural “borders” coupled with an imaginary breaking down of such barriers.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trying Hard Here

youtube

Diasporic narratives can be understood as both extensions of and reactions against globalization. Several of the frameworks for understanding diaspora that we’ve encountered appear to counter many globalist objectives. Appearing in many diasporic texts, what can be understood as a sort of emphasis on the specific. Hall, Cole, Smith and other writers we’ve encountered all try to draw attention to even the most minute ways people are experientially separated from one another or share common ground through constructed ideologies. Finding and dissecting these extremely specific pieces of personal or cultural history allows academics and authors to counter the homogenizing force of globalization. Hall’s understanding of identity presents the diasporic subject as a byproduct of a complex matrix of both internal and external constructions. This forces us to reckon with the many specific ways in which subjects are formed. Hall attempts to push back on the belief in a traditional narrative about the self, wherein a subject is simply disconnected from a homeland and waits to recover it. The myth Hall critiques can be seen as a tool of globalization in the way that it reduces the importance of individual experience and the complex nature of reality.

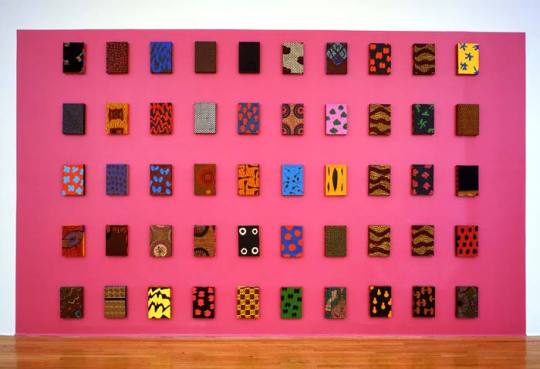

There is, however, an insidious byproduct of this attempt to focus on the specific. More and more it seems that diasporic texts and ideas are being commercialized. It is not so uncommon to see obvious attempts at masking a kind of “othering” process with rhetoric that appears to be genuinely concerned with representing individual identity with all its inherent complexities. There is a British-Nigerian artist by the name of Yinka Shonibare MBE whose work is intimately concerned with exposing these kinds of practices. One piece titled Double Dutch is particularly relevant to this discussion. The piece is meant to mock many western audiences who would approach it and assume that the seemingly “African” cloth is a reflection of Shonibare’s personal history. This is not the case, as the cloths were purchased at a flea market in London and actually produced in Holland. Shonibare is acutely aware of how his success as an artist depends on his ability to present his identity as what many westerners would recognize as African. Shonibare’s 1994 piece is a reaction to a disturbing trend that has remained present since Double Dutch was first displayed. Identity has become marketable as “otherness” while the negative consequences of such a practice is often obfuscated through the appropriation of rhetoric such as Hall’s.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reflection 2

As we approach the end of our unit on globalization, I am struck by the way in which several of the scholarly sources utilized by this course feel extremely dated. Having seen the rise of various political moments branded by isolationism, it is strange to see many academics basically assume that globalization is an unopposed force of change in the world. The events of the last year or so make some of these essays read like speculative fiction. I should also say that some of these texts, once likely viewed as radically progressive, seem deeply antiquated in how they discuss sensitive ideas. It was interesting to read the Brexit pieces to unpack the dialectic between globalist and anti-globalist movements that has dominated mainstream discourse recently.

White Teeth and Diary of a Bad Year are, however, still extremely relevant despite political developments that have occurred since they were written. Being far broader in their concerns and far less didactic in their inquiry, these works offer multiple profound lenses through which to understand issues in contemporary society. White Teeth in particular has stuck with me. It is a novel that both completely comes together as a narrative and simultaneously fragments itself into a series of different stories and ideological perspectives. Because I simply don’t feel finished with the enormity of its content, I’d like to examine Smith’s novel for the midterm paper, taking a closer look at its structure. However, if writing on White Teeth proves to be too great an undertaking, I’d like to look back to Gomez-Pena to get a better sense of all the ways in which The New World Border attempted to support his proposed “hybridity”.

Looking ahead, I’m excited to go through more literature on the syllabus with an interdisciplinary approach. As I said in my first reflection, most English classes at Oberlin have little to no regard for incorporating secondary sources and only offer a tiny bit of context for literature on the syllabus. So far, I have not been disappointed in how this class pulls from a variety of different methodologies and disciplines, offering a complete approach to the course’s concerns.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

In response Milo, Max and Poeticconfrontation:

Despite all the ways in which the internet works as a homogenizing force of globalization, recent events have shown that the web has birthed a new and fragmented ideological map. Filled with images of our Facebook friends and advertisements tailored to our search history, the internet can easily be misunderstood as solely a space of homogenization. We often think of our experience of the internet as a litmus test for a sort of imaginary global climate, forgetting that as the internet has expanded it has also separated into a series of different “states” governed by shared ideologies.

I have encountered people who have been raised within a leftist sphere before connecting to alt-right communities through the internet. It seems that there is a kind of movement that occurs here, similar to moving from one city or space to another, wherein one ceases to occupy an ideological terrain that is shaped by a tangible environment and finds selfhood in a reality disconnected from the material world. The same description can also be given for when someone raised in a right leaning environment finds an online community that brings them to a digital leftist space. What seems most interesting to me about the way these spaces function is how they rarely clash. Ideological states constructed through the internet are built over time through affirmation, overlapping yet never truly challenging each other.

These thoughts are inspired by Milo’s discussion of how the internet serves to homogenize the experiences of individuals and the way in which Max sees the internet as a radical space for self-expression. There’s an interesting tension between these two equally accurate points about the function of the web. Communities are formed across continents, building off of shared experience and access to information, and the internet does have a largely democratic structure for equal self-definition across web users. The way in which those two ideas interact is what makes the internet so inscrutable. We join the communities with which we are eager to engage and hear the stories of individuals that we’re ready to accept.

As stated in poeticconfrontation’s post, our digital selves are still inherently tied to reality. People do not go online to find an ahistorical paradise in which oppressive structures no longer apply. Instead, what makes the web most insidious is that certain ideological borders are, more often than not, constructed without the knowledge of internet users. What makes social media in particular so disturbing is the way it obfuscates large scale manifestations of oppression by allowing users to become the center of their own universe for shareholders financial gain. We are subconsciously discouraged from looking at upsetting discourses conducted on pages such as 4chan through repeated visits to increasingly familiar content from our favorite webpages.

The perception of the internet as an “accessible” space has become a sort of double edged sword. It has both allowed for many to find comfort and solace through a digital reconstruction of themselves and encouraged a certain kind of ignorance. Because of how we feel permission to move freely through a virtual space of information, it is easy to forget what lies just past our Facebook or Twitter feeds and the minimal searches necessary to access ideas that many of us at Oberlin would understand to be disturbingly oppressive.

youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

In response Milo and Max:

Despite all the ways in which the internet works as a homogenizing force of globalization, recent events have shown that the web has birthed a new and fragmented ideological map. Filled with images of our Facebook friends and advertisements tailored to our search history, the internet can easily be misunderstood as solely a space of homogenization. We often think of our experience of the internet as a litmus test for a sort of imaginary global climate, forgetting that as the internet has expanded it has also separated into a series of different “states” governed by shared ideologies.

I have encountered people who have been raised within a leftist sphere before connecting to alt-right communities through the internet. It seems that there is a kind of movement that occurs here, similar to moving from one city or space to another, wherein one ceases to occupy an ideological terrain that is shaped by a tangible environment and finds selfhood in a reality disconnected from the material world. The same description can also be given for when someone raised in a right leaning environment finds an online community that brings them to a digital leftist space. What seems most interesting to me about the way these spaces function is how they rarely clash. Ideological states constructed through the internet are built over time through affirmation, overlapping yet never truly challenging each other.

youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

the first and last lines of my post are on this dang building

THE FINE ARTS A HERITAGE FROM THE PAST

We were all encouraged to get off campus, to explore how globalization relates to sections of Oberlin that aren’t inherently designed for the college’s current or prospective students. There are, however, a few places in Oberlin that aim to be both resources for undergraduates and serve the less transient population of this midwestern town. The Allen Memorial Art Museum is just such a place.

Constructed in 1917, the main wing of the Allen is designed to emulate the architectural styles of such places as the Palazzo Medici, while the 1976 extension was created to house more modern “neutral” gallery spaces. With this in mind, one can potentially read the Allen as removed from the history of its surroundings. To what degree is the museum a tool for the college to claim the cultural resources of globalized cities like New York or Los Angeles? Oberlin College tour guides make special mention of the museum’s many offerings to students, careful to highlight how it has been ranked by various publications as the second or third best college museum in the country. Above the front entrance of the museum, one can see inscribed “THE CAUSE OF ART IS THE CAUSE OF THE PEOPLE”. This is a statement that brings into focus a popular conception of arts spaces as transcendent in nature, reflections of collective interests and experiences rather than individual ones.

However, there are several pieces of information to take into account that highlight a commitment to maintaining a link between this college owned space and Oberlin. The museum itself is completely free to enter and often tries to engage Oberlin community members outside of the college in a variety of ways. In addition to offering public programs for Oberlin residents of all ages, the Allen curates its exhibitions with accessibility in mind. The placement of the building, raised and set back from the street, is easy to read as exclusionary and, for me at least, evokes notions of elitism. Yet when the Allen was built it was the only college owned building in its section of Oberlin. It was explicitly designed to be for both student and lifelong Oberlin resident.

In my opinion, both readings of the Allen are completely valid. It is both accessible and impenetrable. How to understand the Allen’s relationship to its surroundings depends on how much one is struck by the museum as a reflection of globalization. I can’t help but see the museum and its many resources as clear demonstrations of the college’s desire to attract students from metropolitan cities as part of a larger effort to make a profit from wealthy families. That said, I want to say that my reaction to the Allen could certainly be rejected by many people in town who see the museum as a point of pride for their community and not an insidious reflection of the college’s desire to push a kind of globalization onto Oberlin.

THE FINE ARTS A GIFT TO THE FUTURE

youtube

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Reflection For Globerlin

I’m here because I have heard from some reliable sources that this course was one of a select few classes in the English department that takes an intensely interdisciplinary approach to textual analysis. It’s important to have the freedom most people take with literary study situated within a profound understanding of a work’s context. For me, this class seems like a constant exercise in accepting my own ignorance. Through this course’s reading list, I’m looking to expand my understanding of the themes of contemporary literature and practice the most effective methods for admitting my lack of perspective and the limitations of my own experience. Most of the texts I’ve studied at Oberlin have been many centuries or decades removed from the present. Such works are extremely palatable due to how they often have only a few cultural concerns and offer didactic lessons for their readers. To paraphrase a point made by Zadie Smith in her lecture at Oberlin, authors now cannot pretend to offer singular answers to the many complexities of living in the present. It is the work of these current authors that I have yet to encounter in an academic setting and hope to study in this course.

2 notes

·

View notes