Text

i do think theres something sad about how largely only the literature that's considered especially good or important is intentionally preserved. i want to read stuff that ancient people thought sucked enormous balls

86K notes

·

View notes

Text

catholic guilt vs protestant belief in your own inherent superiority, fight

171K notes

·

View notes

Text

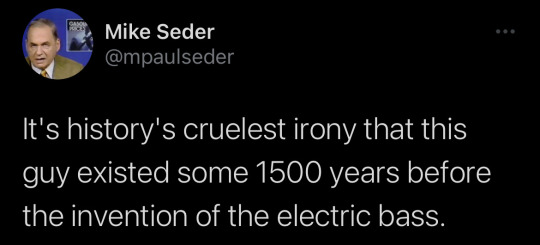

Actual roman epitaph for a dog

135K notes

·

View notes

Video

179K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Visitors to St. Peterborough Cathedral today are drawn to Katherine’s tomb. She was buried with the honors befitting a “Princess Dowager” and the King’s “sister”. John Hilsey who preformed the ceremony, reiterated over and over again that she was not the King’s wife, and that her marriage had been an aberration, and she was Princess Dowager. Her chief mourner was Henry VIII’s niece, Frances Grey nee Brandon, eldest daughter of the late Duchess of Suffolk, Princess Mary Tudor. Also present was Katherine’s long time friend, Maria de Salinas and her daughter, the new Duchess of Suffolk, Catherine Willoughby

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of the most important things I have learned today..

162K notes

·

View notes

Photo

women history meme → noblewomen [1/5]

↳ Ermengarde, Ruling viscountess of Narbonne

“In her own time – in the second half of the twelfth century, when Eleanor was marrying her kings and Marie was hearing the freshly minted stories of Cligès and Perceval – Ermengarde was at least just as greatly known. […] Even more intensely than many of our contemporary politicians, she most likely lived her private life on the public stage. Would she have had any choice if she wished to survive in the world of cunning and blind ambition that was her lot? [Medieval women] were the great women who boasted titles of countess and viscountess, rulers of cities and castles, who roamed the land receiving oaths of fidelity, negociated treaties, settled disputes among the lords of the land, and who occassionnally were to be found heading with their armies at an important siege. They did not match the tinted Victorian image of the mysterious, retiring lady in her castle, nor did they match anything we had read in books on “feudal society”. Ahead of them was Ermengarde.” – F. Cheyette, Ermengarde of Narbonne.

#12th century#french history#ermengarde of narbonne#medieval france#medieval women#admin horrible historian

502 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Marie of Champagne had a close relationship with her brother Geoffrey if we judge by the poets who frequented their two courts and the countess’ reaction to her half-brother’s death. Indeed, apart from her presence at Geoffrey’s funeral, Rigord also points out that Marie wanted to work for the rest of his soul. Geoffrey’s other half-sister, Alix, Countess of Blois, also participated in these foundations. This desire on the part of the two countesses to maintain Geoffrey’s memory shows not only the deep pain they must have felt when he died, but also the immense human qualities they recognized in him. On the part of a character like Marie de Champagne, this is a testimonial of esteem and friendship of great value which should have been better taken into account. It should be noted that Marie never again made such offerings for the repose of the soul and the memory of one of her relatives. Her son Thibaut continued to give money for the memory of Geoffrey after the death of his mother, just like the son of Alix de Blois, Count Louis, who in September 1200 paid an annual donation for the soul of his “dear uncle Geoffrey”, according to his mother’s will. All this clearly shows that the Duke of Brittany had maintained a quality relationship with his two half-sisters, in which literary concerns were certainly not absent.

-Eric Desbordes, Constance de Bretagne (1161-1201): Une Duchesse face à Richard Coeur de Lion et Jean-sans-Terre

#12th century#french history#english history#marie de champagne#alix de blois#Capetian France#plantagenet england#Angevin empire#marie of france#alix of france#admin horrible historian

73 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Favorite History Books || Marie of France: Countess of Champagne, 1145–1198 by Theodore Evergates ★★★★☆

Countess Marie of Champagne is known today primarily as a literary patron, notably of Chrétien de Troyes, who famously announced in his prologue to Lancelot, that since she “wished” him to tell the tale, he complied with her “command.” From that and several other mentions by contemporary writers, Marie has been cast as the animator of a “court of Champagne.” It is indeed ironic that, with few explicit references to her patronage, Marie is now cited more frequently than her husband, Count Henri the Liberal (1152−81), a commanding figure in his time who made the county of Champagne one of the premier principalities of northern France and whose intellectual interests are amply attested. Marie in fact was more than a cultural patron. She was ruling countess of Champagne for almost two decades in the 1180s and 1190s, initially during Count Henry’s absence overseas, then as regent for her son Henri II and as co-lord with him during the Third Crusade and his subsequent residence in Acre. From the age of thirty-four until her death at fifty-three she ruled almost continuously, presiding at the High Court of Champagne and attending to the many practical matters arising in a vibrant principality of the late twelfth century. She acted with the advice of her court officers but without limitation by either the king or a regency council. If Henri the Liberal’s crowning achievement was to create the county of Champagne as a dynamic, prosperous state, Marie’s was to preserve it in the face of several existential threats.

Historians of Capetian France have yet to appreciate the frequency and significance of wives acting in the absence of their husbands and during the minority of inheriting sons. That was a common family practice; only in a wife’s absence was a guardian or regency council appointed. During Countess Marie’s lifetime two royal regencies were necessitated by the absence of a resident queen while the king traveled overseas: when her mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, accompanied Louis VII on the Second Crusade, and when Queen Isabelle died in childbirth shortly before Philippe II left on the Third Crusade. In each case the king designated regents as guardians of the realm. Louis appointed Abbot Suger of St-Denis and the seneschal Raoul of Vermandois “for the custody of the realm” (de regni custodia), said Eudes of Deuil, while Philippe enacted an ordinance (ordinationem) granting his uncle Guillaume, archbishop of Reims, and his mother, Adèle, the dowager queen, limited authority during his absence.³ Countess Marie, however, like most wives of princes, barons, and knights, was not burdened by a regency council. Her decisions at court and her letters patent carried the same authority as those of her husband and son, without mention of any provisional standing. Although she often associated her underage son with her in letters patent, she alone exercised the full plenitude of the comital office, even during Count Henri II’s extended stay in Palestine, and she sealed in her own name as countess of Troyes (her only title).

Marie’s life beyond her role as literary patron and ruling countess encompassed an extensive network of family relationships, for she was connected by birth and marriage to two of the most prominent royal families of twelfth-century Europe. As the daughter of Louis VII and Eleanor of Aquitaine, Marie acquired through their second marriages numerous royal half-siblings whom she regarded as brothers and sisters: Louis’s children Marguerite of France and King Philippe II, and Eleanor’s sons Henry, Geoffroy, and Richard. Even more directly important in providing a nexus of personal support for her rule in Champagne were Henry the Liberal’s well-placed siblings: the royal seneschal Count Thibaut V of Blois (1152–91), Archbishop Guillaume of Sens and Reims (1168–1202), and Queen Adèle (1160–79, d. 1206). Marie’s seal inscribed her dual identity: “Daughter of the King of the Franks, Countess of Troyes.”

#12th century#french history#marie of france#marie de champagne#Capetian France#admin horrible historian

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

181K notes

·

View notes

Text

The chronicle of the monk Herbert of Reichenau for the year 1021 ends “My brother Werner was born on November 1.“

1021 was not an uneventful year. The emperor began a campaign into Italy. Illustrious abbots died. There was an earthquake. But Herbert took the time to note, at the end of the year, that his brother was born.

Of such acts of tenderness is history made.

120K notes

·

View notes

Text

You ever think about how unified humanity is by just everyday experiences? Tudor peasants had hangnails, nobles in the Qin dynasty had favorite foods, workers in the 1700s liked seeing flowers growing in pavement cracks, a cook in medieval Iran teared up cutting onions, a mom in 1300 told her son not to get grass stains on his clothes, some girl in the past loved staying up late to see the sun rise.

144K notes

·

View notes

Text

im not even joking rn this fucking painting made me start uncontrollably sobbing. Do you know how long it took to paint? How expensive it was? The cat was content for hours and so loved that the girl held him there and paid for him to be painted with her. Imagine having such a bond… imagine being so loved and loving so much back…

139K notes

·

View notes

Photo

When most people think of the Death of Cleopatra, they think of something like the above pictures. Cleopatra lying on a couch, or standing there clutching a snake to her exposed breast. Or, as in one of the above cases, with the fabled serpent biting directly on to her nipple. She is almost always nude or nearly so, practically inviting everyone to gaze on her body as she lies there in her death throes. She is frequently delicately pulling her gown down to give the viewer a perfect view of her breasts. Often her equally unclothed handmaidens are falling over her in their own death throes, or gesturing dramatically to better showcase their nudity. There are also usually several other people portrayed there as well, staring down at the nude, or nearly so, Queen’s corpse.

It has been, and will likely continue to be, a popular theme in art to depict her that way. It used to be a titillating thing, an excuse to paint a beautiful nude/semi nude woman. She’s been immortalized as such in sculpture, paintings, wax figures, and everything in between.

This image of her though, is a myth. Pure and simple.

Stacy Schiff, the author of “Cleopatra: A Life” describes her death like so:

Cleopatra lay on a golden couch, probably an Egyptian-style bed with lion paws for legs and lion heads at its corners. Majestically and meticulously arrayed in “her most beautiful apparel,” she gripped in her hands the crook and flail. She was perfectly composed and completely dead, Iras very nearly so at her feet. Lurching and heavy-headed, almost unable to stand, Charmion was clumsily attempting to make right the diadem around Cleopatra’s forehead. Angrily one of Octavian’s men exploded: “A fine deed this, Charmion!” She had just the energy to offer a parting shot. With a tartness that would have made her mistress proud, she managed, ”It is indeed most fine, and befitting the descendant of so many kings,” before collapsing in a heap, at her queen’s side.

Charmion’s was an epitaph no one could dispute. (Nor could it be improved upon. Shakespeare used it verbatim.)

Cleopatra went to her death as she’d lived her entire adult life, as the Queen of Egypt. She had her royal robes and ornaments on, and was thus fully dressed. She knew full well Octavian and his men were going to burst in on her, were going to find her and her ladies there dead. There is no chance she was going to be lying there undressed when a room-full of strange men were going to be looking at her. Cleopatra made sure she went first, so that her ladies could arrange her so nothing inappropriate would be seen. As far as we know, the only ones there at the time of her death were her and her two handmaidens, as they had barricaded themselves inside her mausoleum.

It’s likely all the nudity also stems from propaganda spread by Octavian both during her life and after her death, painting her as a whore and a seductress. Of course she would be naked she was the decadent Eastern Queen who seduced men with her witchcraft! It’s just one of the many, and increasingly ridiculous, misconceptions that’s been spread about her since her death and one that people should realize was certainly not true. The snake is now widely regarded by most scholars as a myth as well, since it’s far more likely she took some kind of poison to end her life instead.

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

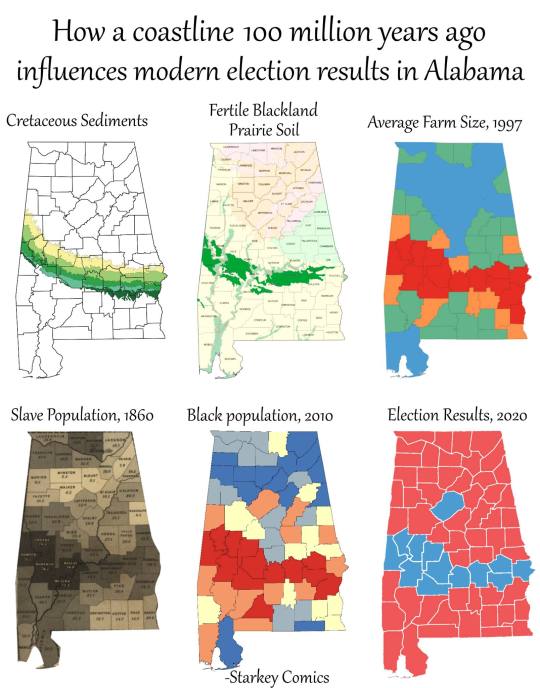

How a coastline 100 million years ago influences modern election results in Alabama.

34K notes

·

View notes