a film and television review blog

Last active 2 hours ago

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

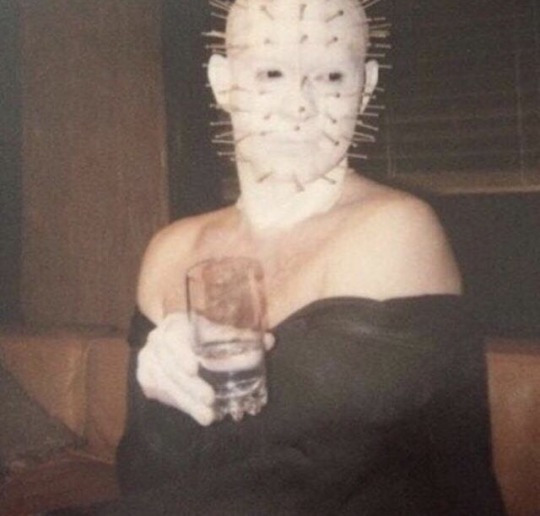

honestly nothing for me will top the energy of BTS photos/videos of horror movie monsters/demons/creatures/etc in full makeup just hanging out… like

energy….

128K notes

·

View notes

Text

Jumanji: Welcome To The Jungle (2017) Dir: Jake Kasdan

I have been reviewing a lot of Oscar nominated films lately, but I did want to do a short review of a film that I had pretty low expectations of and was pleasantly surprised by.

Jumanji: Welcome To The Jungle is not a remake, as I assumed, but a sequel to the original. Surprisingly it doesn’t fall into a lot of the common sequel traps - its links to the original are sparing, and it doesn’t attempt to bring back any of the original characters and cost on the easy nostalgia of that. Even though it’s a sequel it invents its own world and relies largely on its own rules and characters to leave an impression. The basic plot involves the board game transmogrifying itself into an old fashioned video game cknsole, and four teenagers being sucked into the game as the characters they picked to play.

The style of the film - scared teens being pulled into a world that isn’t just the narrative of a game or movie but also operates with the conventions of the medium; titles, menus, flashbacks, cutscenes, that appear around the characters - reminded me of a film I saw in 2016, The Final Girls, in which the teen protagonists are pulled into a 80s slasher film and experience similar things, crossed with the jungle-set comedy Tropic Thunder where a bunch of self-centered actors have to work together to get home. Where TFG played it both for comedy and horror, J:WTG is smart enough to realise it won’t beat the original in terms of genuine scares (it wasn’t a horror but if you ever watched it in your childhood you know what I’m talking about) and goes a more direct action-comedy route. It’s a fairly self aware movie, making digs at the design of women in video games, and a few nice Scott Pilgrim-esque moments in nod to video game knowledge.

The cast is strong, and works well together. The actors playing the teenagers don’t actually get much screen time to play their characters before their roles get taken over by the main cast, but they have nice chemistry with each other and do well with the time they have. Dwayne ‘The Rock’ Johnson is a solid comedic lead, and has worked with Kevin Hart before - they’re a good duo, especially if you enjoy seeing Hart as the fall guy for a lot of jokes.

I really liked the surprising duo of Karen Gillan and Jack Black - both teenage girls in the bodies of a attractive, skimpily dressed woman and an chubby, professorial man, which is very uncomfortable for them both - because it subverts expectations of what should happen when a smart, nerdy girl and a seemingly vacuous popular girl have to work together. They get their issues out of the way early on and spend the rest of the film helping each other out. And nary a boy is fought over. I wondered if this counts as passing the bechdel test? Strictly speaking, no, as the actors are a woman and a man, but the female bonding between the two female personalities within those bodies is strong.

I was especially assuming that Jack Black’s portrayal of a teenage girl wouldn’t exactly be nuanced but he unexpectedly treats the character in a way that she is funny, but she is rarely mocked just for a being a “social media obsessed” teenage girl - he respects her enough to portray her intelligence and growth in her own areas of experience.

It’s surprising, then, that the film does so well dealing with a friendship that only develops in the game, but with the one ir sets up from the beginning it almost underwrites? The boys, Spencer and Fridge (who become Johnson and Hart) are revealed early on to have been childhood friends who aren’t close as teenagers, unless Fridge needs Spencer to write a paper for him. The film sets this up as the friendship that needs fixing but almost forgets to do this - there’s no real moment of understanding between them about where their friendship went wrong, just accusations in a fight that is never really resolved, and a conversation about being brave at the climax. We see Spencer’s insecurities, it would have been nice to see Fridge’s and actually see that fence mended instead of just seeing that they are apparently friends again at the end without any resolution from their issues.

I didn’t even hate Nick Jonas! He’s fine as a 90s teen stuck in the game, unaware of for how long, that Bethany/Shelly (Jack Black) has a connection with. This ends fairly well for him, as the game ending means he resets to when he went in, but less well for poor Bethany, who next sees him when he’s in his late thirties with a family.

All in all, a fun movie that doesn’t need to be taken too seriously. 3.5/5

1 note

·

View note

Text

In I, Tonya everyone’s a winner, baby

I, Tonya (2018) Dir: Craig Gillespie

I’m sure this movie will be polarising – it’s the kind of movie you might really, really love or definitively hate, as is the case with most biopics. Especially if viewers remember the original incident at the 1994 Lillehammer games, and have their own opinions on what happened. I, being less than a year old and over the other side of the world, didn’t and so I was excited to go in with only my vague cultural knowledge of the Kerrigan/Harding incident,

Firstly, the good: the performances. Allison Janney is, as always, brilliantly brittle as LaVona Harding, Nancy’s emotionally withholding, abusive mother. She never shows a moment of affection for her fifth child (the only one she seems to be in contact with) until a scene at the end of the film – and even then it’s stilted and compromised by one last betrayal. The end credits show a clip of the real LaVona being interviewed and you can see how Janney deftly captured her mannerisms, without making her too much of a joke.

Margot Robbie is also brilliant – this is the role she’s been looking for, in perhaps her entire career so far. I remember the beginning of her career on Neighbours and wouldn’t have necessarily have believed she could give the performance she does here. So I’m oddly proud to see her give it her all here and be rewarded with a Best Actress nomination for it. Her Tonya is a sympathetic character, raised in abuse and poverty, abandoned by the only parent that ever showed her affection, and then trapped in another abusive relationship that starts when she is just fifteen. But Robbie isn’t afraid to make her unlikable, brash and rude at times. She’s not even afraid to look unattractive – which shouldn’t be such a big deal with female-led Oscar nominated films, but here we are – to make her Nancy seem as real and close to the truth of a woman living in near-poverty into adulthood, trying to compete in a sport populated by middle and upper class women. Her Tonya feels like a real person – not a saint, but not a sinner just because she’s uncouth and poor. Robbie plays her as someone who has worked three times as hard to get past class barriers and become the one-time best figure skater in the country, driven but flawed, someone who also has trouble taking responsibility or admitting fault. This is a very interesting part of Tonya’s characterisation that I feel the script doesn’t do nearly enough with – but more on that later.

Sebastian Stan has quietly become a very talented character actor in the last decade – much like Robbie, I don’t know if anyone watching teen fare like Gossip Girl and The Covenant might have expected this from him – but it’s truly on display here. His Jeff Gillooly is almost a double role – the meek, glasses-and-goatee wearing older Gillooly, being interviewed as part of a framing device, and the violent, alcoholic, needy young Gillooly of the older Tonya’s recount of events. Stan manages to find a kernel of humanity in the character, who consistently plays out a typical abuser behavioural pattern with Tonya: he hurts her, then feels very guilty and remorseful later, calms down for a while, then the cycle starts again. You can tell that he desperately loves her, but his low self-esteem issues and resentment of her commitment to skating, maybe even her success, cause him to constantly lash at her. That isn’t an excuse though, and even though Tonya can often be difficult he always goes too far in reaction, less sympathetic everytime he does. Stan plays Gillooly’s role in the assault of Nancy Kerrigan as that of the smartest idiot in a group of astoundingly idiotic men. His original, badly thought-out plan is just to get some men he’s never met to post death threats to Kerrigan in the hope of spooking her. It evolves into a horrifically mismanaged assault plan, given the go ahead by their contact, Gillooly’s deluded idiot of a friend, who is Tonya’s “bodyguard”. The script, and Stan, portrays him as definitively not signing off on this drastic change, but being unable (or unwilling to implicate himself) to stop it. Stan makes watching him spin further into paranoia and fear darkly entertaining - from his manic behaviour to, when finally given up by his wife after a final abuse, meekly co-operating with the feds and apparently keeping her name out of it.

This movie belongs to these three actors, but I’m going to quickly mention Paul Walter Hauser here - who as “bodyguard” and friend to Gillooly, Shawn Eckhart, gives a marvellously deranged performance in the third act, drunk on the power and infamy of organising something with such national attention, and having delusions of grandeur about working for government intelligence (ironic, considering how little he does to hide his or Jeff’s involvement in the crime.)

The cinematography is harsh but fluid, Tonya breaks the fourth wall a lot as the camera tracks her movement in skating, in fights, in driving away. This fluidity really works for a film about film skating, capturing the potency of Tonya’s routines – although for the famous triple axel it was considered too dangerous for a stunt double to even attempt, as the real Tonya was the first American woman to land it, and so the one seen in the film is CGI. The narrative framing devices are three separate interviews with Tonya, Jeff and LaVona, and it’s all very slickly put together with footage of the real interviews and Harding in competition playing over the end credits.

This where the bad comes in – despite all of these tricks: the fourth wall breaking, the moments of meta-narrative comment on the biopic narrative (such as a moment of Tonya shooting a shotgun at Jeff and then saying to camera, “I never did this!”) daring the viewer to contradict the presented narrative – the film doesn’t really ever contradict Tonya’s narrative, which makes up the majority of how the story is presented in the film. It tells a straightforward, tragic story about a woman in hardship who was flawed but didn’t deserve to lose her only joy in life. Now, given that I have little knowledge of the incident I can’t say that I actively disagree with the level of accuracy in this presentation of Tonya Harding’s story. My problem is that this film doesn’t present itself as a straightforward, tragic biopic about a polarising public figure. The marketing, and the framing devices of conflicting interviews give the appearance of a narrative that won’t be straightforward, seemingly asking who’s version of events should we believe? What is closest to the truth?

But unfortunately, Steven Rogers’ script isn’t really clever enough to pull this off – it presents two other accounts of the narrative, but privileges Tonya’s as the gospel truth. It’s a shame, because making the truth of events murky would actually make the script make more sense. The disparity between modern-day Gillooly and the film’s Gillooly, and how he was involved – the film can’t resist letting even him off the hook for the assault plan, when it’s not unbelievable that someone with a history of violence could be fine to, at the very least, organise the assault with someone. To take the film’s word, neither Gillooly nor Harding actually had a hand in the conception or carrying out of the plan to violently attack Kerrigan, just the one to mail death threats to her – in which, Harding is barely involved, and uncaring whether or not it goes ahead. There was a note, though – featured briefly in the film – with Harding’s handwriting detailing Kerrigan’s practice times and place. Why would she have needed to give that to anyone to send letters? The narrative works against itself, creating a pattern of Harding not taking responsibility for her own mistakes that never pays off, and a confusing, and ridiculous final speech about truth, featuring the line “there is no truth” – what does this even mean in the context of narrative that never attempts to present any other truth other than the person saying this?

Ultimately I think Rogers, and director Craig Gillespie, tried to do both – a straightforward biopic and an almost Rashomon-like look at a widely debated event from several perspectives, and in trying to do both, both ideas let each other down and take away from an otherwise gripping film. Thankfully, the performances are so engaging it almost doesn’t matter. Almost.

3.5/5 stars

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I Find You All Around Me - a film review

The Shape of Water (2017) - Dir: Guillermo Del Toro

I haven't seen much of the discourse around The Shape of Water, so I won't try to address it in this review.

Was it a perfect film? No, but I absolutely loved it. It's such a strangely intimate film about lonely, downtrodden and otherwise abused being being saved solely through compassion and their connection to each other. Maybe that's cheesy, but right now, I'll take it as what we can do together - we might feel individually powerless but together we are actually stronger than the small minded homogenous blob of men in power (represented by Michael Shannon's character, Strickland). It's important to remember this is a film by a Mexican director living in the US.The cinematography is gorgeous, soft and lush, making 1960s Baltimore look like a fairytale - bringing to mind the modern-fairytale New York aesthetic of 2008's Penelope - even though the narrative is very much aware of the unfairytale-like nature of the main characters' realities.

There are a range of different shades of blue on uniforms, cars, set dressings, wallpaper which lend the world and elegant, cozy feeling, especially when coupled with the constants of night and rain. Guillermo De Toro's set design and costuming is always a highlight of his films but this might be my favourite, realer than the gothic trappings of Crimson Peak but softer, warmer than Pacific Rim.

The most important protagonists of the film are all outsiders in some way, almost powerless to fight the injustices and loneliness that comes from this status.

The two female mains are arguably the visible outsiders: low-ranking cleaners, one who is a black woman, Zelda (Octavia Spencer) and one, Elena (Sally Hawkins) who has a Latina name and was raised by Latina nuns (it's not specified whether Elena is actually Latina, but Hawkins is Caucasian so I assume the nuns named her.) They work at a big government facility, at night, where the cleaners are largely women of colour and the people in charge are uniformly white men. Elena is also mute, communicating mostly with Zelda in sign language. The world sees her as meek, insignificant, even when they don't know that she is mute. She and Zelda are nearly invisible in their insignificance to these men. Shannon's Strickland even urinates at a urinal while they're cleaning the men's bathroom, telling them to go on like he isn't there, either sadistically enjoying or callously uncaring about the extreme discomfort this causes them. Zelda and Elena have each other, but both are lonely - Elena is unmarried and an orphan, and Zelda is in a tiring, loveless marriage to a man who never helps her. This is perhaps, what draws Elena to what she finds in the lab one night - an 'asset' brought in by Strickland that turns out to be a fish-man creature that they are studying to attempt to get an edge on the Russians in the Cold War.

The other two outsider main characters are invisible in a different way. Richard Jenkins' Giles, Elena's next door neighbour and close friend (a performance I think deserved SOW's best supporting actor nomination far more than Michael Shannon, who while a great actor doesn't have much to do but be menacing in his role) and Michael Stuhlbarg's Hoffstetler (I already said this in my CMBYN review but it is a CRIME he wasn't nominated for either film) are visible to the world, seemingly 'normal' - white, heterosexual American men, who can mix amongst the 'progress-and-military-might' antagonistic types that run the facilty. But they are just as lonely. Giles is a closeted homosexual in his sixties - who buys pies he doesn't need for an excuse to talk to the handsome, but most likely heterosexual young man who works at the pie shop. Hoffstatler is a scientist working on the fish-creature project, who is secretly a Russian spy - yet a good hearted one, an immigrant who agreed to help his country but just wanted to learn about the creature, not be complicit in torture.

The enemy in this is men like Strickland and the majority of men in charge at the facility - who would call not only the creature an "aberation" but likely all of them for who they are, for all the ways they aren't homogenously white, heterosexual male Americans. Compassion is anathema to them - it's part of what sets Hoffstetler apart even as he pretends to be exactly, unremarkably like them. It's also, again, a saving grace of connection for the mains, and what really does save a life in the course of the narrative.

If you're reading this review, you're probably aware that the central romance is between Elena and the humanoid shaped fishman. What I was surprised by was how tender and romantic, and not graphic their relationship was as it developed. I went in expecting something beautiful, but bracing for some uncomfortable things, but their relationship develops slow and tentatively and I was very moved by it. Some reviewers (I'm sure you can guess gender) questioned how likely it would be that she would fall for the creature when there are human men around. To that I say it's nothing new - just because you can't fathom why a woman wouldn't want to date men doesn't stop it from happening, whether it's a fishman or a woman, or someone else. I also saw a male reviewer refer to Elena's "rampant sex drive" because we see that masturbation is built into her evening/getting ready bath routine. Maybe they meant well, but it frustrated me because female masturbation is not often seen in mainstream films. Women can only be seen sexually through the eyes of another, because female self-pleasure and sexuality is taboo and something to be ashamed of. So thank you, Del Toro, for making this such a normal, routine part of this film - not gratuitously showing us the full act for voyeuristic pleasure, but solidly making us aware that this is a regular, healthy part of this meek-looking woman's life. That's a real feminist action.

One of the most moving elements of this film was over the connection that Giles and Elena have - they support each other when they're home, she cooks eggs for him, he understands sign language and goes out to eat with her. It makes them less lonely. But they have the visible/invisible otherness divide and it almost breaks up their friendship at one point. She - always visibly marked as different - likes that the the creature doesn't know how she's "broken" and wants to rescue him from the planned vivisection - but when she begs Giles to help her, he baulks. He's safely lived his life invisibly, navigating the 'normal' world without breaking the rules and he's just about to possibly be welcomed back to his job. It represents stability and normalcy, and her plan is dangerous, illegal and scary. But when he gets home after one of the most humiliating and alienating days of his life, both professionally and personally, he realises how he will never be a part of that normalcy, and that she is all he has in a unfair, lonely world - and he pledges to do whatever he can to save her from the same misery. It's a tragic, gorgeously acted scene and reader, that is when I cried.

There are some disturbing things in the film - surprisingly unrelated to the interspecies romance - that I didn't think worked. Michael Shannon is a great actor, who is very good at menacing roles but I didn't care about the film's attempts to show his life and pressures because I wasn't invested in him as more than an antagonist. I did not enjoy the somewhat violent sex scene between him and his wife, either, though I am sure it was included as contrast to the sweet romance of elisa and the creature. I even think the time they spent on that might have been better given to giving Zelda more to do in the narrative or showing more of her life. But that was probably my only issue with the film.

Otherwise I feel like this film was almost calibrated for me personally - there was even a dream sequence Old Hollywood-type musical number! All in all, I found it a beautiful, moving, surprising and well made film that I think may be Guillermo Del Toro's finest to date.

0 notes

Text

I saw three movies in the last week. They were pretty different to each other, but I quite enjoyed all of them, so I'm resurrecting my film blog to write reviews of them. To 2018, and resolutions to write more!

Call Me By Your Name (2017) Dir: Luca Guadagnino

I was very interested in this pre-release, even though I had never read the book. Luca Guadagnino caught my eye with 2015's A Bigger Splash, which is stylistically very familiar to CMBYN, and which I really enjoyed. Guadagnino shines in the aesthetic of his films, in the beautiful scenery and silences between sparse dialogue. Both create a languid, sumptuous mood - wealth and privilege on show, yet somehow not ostentatious to the viewer.

But where this mood creates distance and miscommunication between the characters of ABS, it brings the characters of CMBYN closer, creates warmth between them, bringing the viewer into Elio's extended family as easily as they welcome Oliver. The film is set over a summer in Northern Italy in 1983, and Guadagino skillfully captures the feeling of a slow, lazy summer pre-internet, where all there is for the teenaged main character, Elio (Timothée Chalamet), to do is lie around the pool swimming or reading, long family meals, piano practice or biking into town.

Before I go any further, I have to discuss the opening credits, which go on for at least ten minutes and effortlessly set the tone for the casual opulence of the world of the film. Gentle, upbeat classical music plays over photos of classical sculptures - something that Elio's academic father and the grad student who he invites to work with him over the summer seem to be working in the field of - while the credits are written in a messy but elegant script, in a warm yellow shade. All of this somehow worked to already create the mood that pervades the rest of the film - casual wealth and intelligence, warmth and inclusion - before you even meet the Perlmans, and the beautiful villa they spend holidays in.

Some viewers might dislike watching films with wealthy people languishing in villas on holidays, but in the way that Guadagnino presents it, it's enchanting. I loved the feeling of seeing the easy, comfortable way the Perlmans (Elio's family) live on holiday, with their freshly made apricot juice and their family meals in a shaded grove. As I mentioned earlier, it creates a very welcoming vibe that helps you understand the mindset of the newcomer to this idyll, grad student Oliver (Armie Hammer).

The movie is really Chalamet's, and more on him below, but Hammer does quite well in a less showy role as Oliver - who has been invited to spend six weeks at an Italian villa working with an academic he seems to not have personally met before arriving. A great honour, clearly, but it's also awkward, and Hammer plays this slight dissonance well - he's a non-European American (like the rest of the Perlmans) which is both exciting and awkward to the gathered family and friends of the Perlman. Hammer's Oliver is a lot of contrasts, both interested and scared/offended by Elio, both very confident towards him and very hesitant, both cool and dorky. Armie Hammer's being doing a few lower budget indie, and more off the wall projects since the Lone Ranger debacle didn't launch him into the leading man blockbuster stratosphere, and personally, I think he's much better in these than attempting to be another leading man type. (And for that matter, I am genuinely annoyed both he and Michael Stuhlbarg were passed over for Oscar noms, so they could give two to Three Billboards. It's not like Hammer would have got it, but I think he certainly deserved the nomination.)

As I said though, Chalamet is the standout - it's his story and he does a lot with it. His Elio is very reminiscent of the frustrating uncomfortableness of being a teenager - he's awkward, moody, bitter, cheeky, afraid, delicate and above all, real. What was beautiful about this film is how much everyone loves Elio - he's not always kind and good, but he is also a teenage boy - but his sexuality doesn't shut him off from other people. It's not an isolationist story, like a lot of queer film narratives are. While I can understand the urge to show that side of things, it's incredibly gratifying to see a film about a queer boy in the eighties, where if everyone doesn't know for certain they probably are aware of it in some respect, and they don't seem to care. They just love him, and Chalamet plays Elio's connections with everyone (not just Oliver) beautifully. He certainly deserves his Oscar nomination, even though he's not the favourite to win. He's also in the Oscar nominated Lady Bird, and my feeling is that (hot take alert) he's gonna be big.

Further from this, I love how tactile the characters in this film are. Elio is very cuddly and childlike sometimes with his parents, who are very affectionate to him - and no one tells him "a seventeen year old boy shouldn't do that" which is a blessing. He's very affectionate with the girls he's friends with. His later dynamic with Oliver - once they've admitted to feeling something for each other - is very affectionate too, kind of awkward but in a sweet way. Not all their encounters are just these highly eroticised moments (which is not to say that none of them are). This makes their burgeoning relationship very real, like a seventeen year old boy fumbling his way toward a relationship that will always be meaningful, a first love more than just lust. Not that his dynamic with his sort-of girlfriend Marzia is unloving, just different, but no less sweet in its newness to the both of them.

On that note, I'm sure some people will say that there was a “lack of explicit sex scenes” in this movie. To that, I say PAH. It’s not like this movie is sanitised and sexless (hello, peach scene. yep.) It’s quite erotic in parts, quite good at conveying Elio's attraction to Oliver, and vice versa. But it feels like (unlike hetero love stories) that queer media is often all or nothing: either completely sexless, even affectionless even in a good relationship (Mitch and Cam on Modern Family didn’t even kiss on screen till like mid season two or three) or incredibly sexualised, and featuring intense sex scenes. This movie walks the rare line between the two - very affectionate (in private, natch) but allowing them the dignity of not being watched - as they always are, even by relatively benign eyes around them - in the moment of consummation. (For more on this - Jason Adams' delicate and moving review, Call Me With Kindness) It’s not even as though there are no on-screen sex acts in the film, either, so I'll say that I think it was a good, well-done balance.

If I had any slight problem with the narrative, it was that I found it hard to understand the progression of Elio and Oliver's relationship pre the mutual reveal of feelings - but that seemed to be a stylistic choice, and ABS was much the same, where the characters barely verbally communicated for a lot of the beginning arc of the film. It could be deliberately unclear- neither of them really know what the other thinks of them until they admit things together, while they're alone for once. Either way, it didn't much mar my enjoyment of their story which is emotional and complex but also very sweet.

The last thing I have to talk about is Michael Stuhlbarg, who is rapidly becoming one of my favourite actors (and who again, I am furious has not picked up any Oscar nominations for any of the great work he did in 2017). He was in two thirds of the films I saw recently, and he managed to be very moving in two small-ish roles. The scene where he tells Elio not to mock his friend and his male partner, that if he can be as knowledgeable as him and as good he'll be "a credit to him". Elio's father is a good man, and you can tell from this moment he doesn't care who Elio loves as long as he doesn't grow up boorish and ignorant. In fact, as much as the love story is engaging, my favourite scene of the file is when Elio and his father discuss Oliver after he has left. It was incredibly affecting to me - Elio's father doesn't come out and say he knew for certain about them, but refers to their "friendship" in the kindest, most respectful way, possibly even hinting about his own sexuality - not necessarily that he's closeted, but that he may have had an Oliver in his past he was too afraid to have anything happen with. Stuhlbarg is just so good, so affecting and plays really well off Chalamét, who allows Elio just the right amount of vulnerability and emotion.

Not to mention, Sufjan Stevens' two gorgeous original songs for the film, but I'll close this out by saying that there's a certain kind of idea about the kind of queer romance film that gets the Academy's attention - that it has to be sad, that the characters have to suffer and end up unhappy, and everyone can discuss how tragic it was. That sort of story is fine, because yes historically many LGBT people couldn't be open or take chances, and many did suffer. But that's not the only LGBT narrative to be told, even when set decades ago - and I'm thrilled to see films like 2016's Carol, 2017's Best Picture Winner Moonlight, and CMBYN tell a new kind of queer narrative where the characters are allowed to be happy even in an oppressive time, where the characters can break up and be miserable because of that (and not because of illness or bigoted violence), where the focus is just the love story. It gives me hope for the generation of younger LGBT viewers to see themselves outside of misery narratives.

4/5 stars

#call me by your name#cmbyn#luca guadagnino#timotheé chalamet#armie hammer#michael stuhlbarg#film review#oscars 2018

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The pitfalls of the Swedish Neo-Noir effect

Marcella – Season 1

C-

(Spoilers Ahead)

Ah, what a disappointment. As a viewer, I personally love stories with various different characters. I don’t mind random subplots – but they are a lot to take on, and thus hard to do well. If a narrative has several seemingly unrelated subplots, you have to take care to make sure they all coalesce into a narrative that at least mostly makes sense and is satisfying. Especially when you’re a week to week drama, and yet I binged the entire eight episodes of Marcella over a 24 hour period and I had trouble keeping up with everything happening.

Marcella is an interesting enough conceit, albeit a character archetype we’ve seen in lots of other detective shows – ‘anti-social, aloof, brilliant lone wolf detective’, stop me if you’ve heard this before – but I was interested in the idea of the female anti-hero. This isn’t as common as it is with male anti-heroes in much lauded dramas, as if they are allowed to be complex but a female character has to represent her entire gender and either be lovely, or the underwritten bitchy woman. She’s at the end of her tether – her husband breaks up with her at the beginning, she misses her kids who are at boarding school and seem to miss her less, and to cap it off she has terrifying stress blackouts where she loses time and has to figure out what she did during.

This is interesting enough! That’s a lot to go on, given that she becomes aware of her husband’s mistress just before one of these blackouts and promptly finds out the woman, Grace, is missing after she comes to. But then there’s the drama with Grace’s family who own the company that Marcella’s husband works for. That might be enough, but episode by episode there are more and more subplots that build up, supposedly connected but by the end almost feeling largely like unnecessary red herrings the writers put in so they could pat themselves on the back for being so clever that no one figured out the identity of the killer. It’s all a bit too self-satisfied.

An early subplot with a streetwise hustler and webcam stripper, Cara, was one of my favourites and it ended unnecessarily cruelly. I might point out that she is one of three confirmed LGBT characters on the show, and none of them really end the season in a good way. At least the couple, Matthew and Yann don’t die, but they go through a lot of trauma and we aren’t allowed the catharsis of seeing them reunite. That annoyed me, because if you put effort into investing us in unrelated characters and plots and then drop them once they’ve served the greater story, you’re kind of betraying the audience. On that point, maybe it was me but I felt like they were deliberately dancing around whether there was something between Henry and Matthew. Yann’s deliberate jealously was a large part of his plotline, and yet none of that ever came to the fore. It might even have been a crappy smokescreen to stop us from thinking he was even attracted to women. Whatever it was, I don’t think it was handled well.

So many of these subplots never tied into the main plot and thus felt like a waste of time at the end – coincidences and stretches of belief and gaps in logic were never explained, making them more glaringly irritating. The most annoying though thing was the messy and without merit denouement, which seemed so pleased with revealing the killer as someone the audience wouldn’t logically have guessed it forgot to tie it to most of the subplots or indeed anything that came before in way that made any sense. Apart from the idea that hiding your murder amongst a string of serial killings like an earlier case is probably the stupidest way of trying to get away with murder (how do I make sure I don’t draw attention to this murder I want to get away with? I know! By bringing back an old unsolved case and repeating it in a way that’s sure to get a lot of police and public attention, especially since the first case was unsolved!) the actual justification for Henry’s crimes is pissweak. We spend seven episodes with him, hating his stepmother, having conversations that are nothing but how shaken he is by the loss of his sister and how he has nothing for him in England (ESPECIALLY PRIVATE CONVERSATIONS WITH CO-CONSPIRATOR MATTHEW) only to find out that he did ALL of that ridiculous planning, framing and gruesome murdering with targets ranging from a young girl to an old man so his stepmother would like him more, apparently.

Yet the actors are so good with what they’re given, particularly Anna Friel as Marchella and Harry Lloyd’s Henry Gibson (but with strong support from Sinead Cusack, Nicholas Pinnock, Jamie Bamber, Ian Puleston-Davies, Ray Panthaki, Tobias Santelmann, Florence Pugh and Nina Sosanya) that it’s disappointing that their characters end up making illogical decisions and behaving meanly for no real reason. By the end there’s no rhyme or reason to why anyone does what they do, they just clank around snapping at each other and making bad decisions both personally and professionally.

I can only think that Hans Rosenberg and co were sold on Friel and Lloyd’s acting talent and knew they wanted them to be adversaries in the end of the story – but didn’t know how to get there exactly in a way you would never see what was coming and so they cheated a bit.

Lloyd and Friel, it must be said though, play great adversaries. This is especially given that Henry Gibson has been fairly put together for seven episodes and is fast cracking up, allowing Lloyd to showcase a same manic eye-glint and elasticity of features that adds a lot of credulity in the moment to the idea of his psychopathy. Friel’s Marcella unleashes from the unknown well of rage, almost animalistically taking all the stress and grief and rage of her recent experiences out on him, characteristically both harsh towards his early stammered protestations that he stabbed her husband in “self defense” and panicked and soft when hopelessly tending to her husband’s wounds.

Some shows aren’t intelligent enough to ever see the high bar, and so as a viewer you’re not as harsh. They never even had to potential to get there. It’s especially disappointing though when something with the potential to be intelligent and interesting, paired with great cinematography and acting, turns out to miss the bar so completely.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

we’re not ugly people: carol, an old-fashioned love story

SPOILERS AHEAD

I honestly loved Carol.

I’m writing this a while after seeing the film, and a few weeks after the Oscars 2016. I knew it wouldn’t get any awards, and I think I know why. Oscars-bait queer films always seem kind of tragic – someone always dies at the end: a transwoman of AIDS, Jack Twist being beaten to death. This one dares to be a love story between two women, which might possibly have an optimistic ending for them. A hopeful and positive ending, which is something rarely seen in high-visibility Hollywood films about queer people.

This is just a beautiful film. Beautifully shot, with flashback memories shot like a 50s cinecamera (but in colour) and unflinching close-ups on Therese (Rooney Mara) and Carol (Cate Blanchett)’s faces, allowing their reactions to develop slower. The locations are beautiful – New York in the snow, the scenery passing by the car on Therese and Carol’s road trip, Carol and Harge’s imposing stone mansion.

Everyone is really good in their parts. Kyle Chandler in particular could have a thankless role as Carol’s husband Harge, but it was nice that his character wasn’t physically abusive to Carol – she wasn’t embodying the trope of the woman driven to other women out of fear of men. It was very much about attraction to other women and not Harge. Jake Lacy (as Therese’s boyfriend Richard) has a harder job – Richard shouldn’t even be this much possessive over Therese because they aren’t married, and they don’t live together.

Cate Blanchett is always brilliant and here is no exception. She embodies Carol so well, and all her layered feelings with each character are different – disconnection but a sort of sympathy for Harge, guarded WASP sophistication and attraction toward Therese, long-term friendship and solidarity with Abby and love and affection to her daughter Rindy. One of her best scenes is when she goes to a custody meeting with Harge and realises he wants sole custody of their daughter, due to her ‘perversion’. She implores him to allow her regular visits with her child, and gives an emotionally fraught but controlled speech about how Rindy is the best thing they ever gave her, and she cannot be a good parent to her ‘if [she] is to go against her own grain’. It’s such a reasonable and mature way of appealing to Harge’s best sensibilities, and it’s one of the most moving and best scenes in the film.

Rooney Mara is also very good – she’s surprisingly as good at playing a doe-eyed ingénue as she is playing a scary technopunk Swedish hacker. Mara makes her a sympathetic and realistic character, young and struggling with her identity, which is something I’m sure many people can relate to. Sarah Paulson is really good – she both plays a really good friend to Carol that doesn’t seem like she carries long last resentment over the end of their relationship and a helpful character of insight with Therese, warning her that things with Carol can just end, without seeming bitter but also quietly hurt.

That the film begins at the end of the narrative is something only realised at the end of the movie, but it’s such a striking framing device, and jars the audience so much more when we see it happen again in context.

A very well-realised and emotionally moving film.

4/5 stars

#carol#carol 2015#rooney mara#cate blanchett#carol aird#therese belivet#carol x therese#Film Review#review

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

“This is too much madness to explain in one text!”: A cult film in the making

When I first saw Attack the Block in 2011, I thought it would be a fun, but not overly clever sci-fi movie about alien attacking a group of Londoners. What I got was a thrilling, funny and surprisingly intelligent mix of being-chased-by-monsters action and poignant social commentary that became one of my favourite films.

Made on an eight million pound budget (somewhat higher than the average British film budget, but still lower than any of its US contemporaries (BFI, 2009)) from first time writer/director Joe Cornish and using a cast that were mostly teenagers or younger, it could have been a massive failure especially considering the little advertising it got in Australia. But all of the young actors (for many of them, this was their first film role) proved extremely competent alongside more experienced actors like Nick Frost, Jodie Whittaker and Luke Treadaway, and Cornish’s intelligent, authentic-feeling script combined with a great reggae and electronica influenced soundtrack made it a film many critics called a cult favourite in the making (/Film 2011, Reflections on Cult Movies and Classic Television 2012, Yahoo Movies 2011)

There are several different groups of people in the film that start out as distant as possible, and converge in different ways throughout the story: teenaged Moses and his gang (Pest, Biggz, Dennis and Jerome), the teenage girls from their South London estate housing (the ‘block’) Sam, a young nursing student; Brewis, a young, posh boy who lives with his wealthy parents and buys weed from Ron (Nick Frost) who lives in the block and is employed by the film’s secondary antagonist, thuggish and terrifying gangster Hi-Hatz. Moses and the boys are thrown together with Sam only a short while after mugging her, forming a tense and unlikely group. In a nice twist on this trope, she doesn’t let the fact they’re being chased by ‘gorilla-wolf monsters’ let her forget what they did to her and is still fairly hostile towards them until the climax of the film.

Cornish deftly weaves in issues of growing up and social commentary on race and financial status in London into this sci-fi tale; In one scene Moses darkly infers that the aliens are just the government’s next attempt to kill off black and impoverished youth, along with drugs and guns. It’s a heartrending comment, as we can see the cycle that starts with the nine year old kids ‘Props’ and ‘Mayhem’ (two boys called Reginald and Gavin) wanting to be violent and ‘cool’ like the street gang, and ends with teenagers like Moses going down a darker road from mugging strangers to becoming a drug dealer for psychopathic gangsters like Hi-Hatz. Moses and his gang appear terrifying at the start of the film, wearing hoods and scarves, looking dehumanised, and carrying weapons to threaten innocent people like Sam with. Throughout the film they are divested of these layers, these weapons, appearing just as the kids they are and they learn as much from Sam as she learns about them. They realise that she lives in the block too, so she isn’t well-off either and regret mugging her, returning her things at the climax when they are locked in Ron’s weed room. Moses goes through a journey of growing up and becoming remorseful at his violent actions; realising his mistakes throughout the film and bearing that weight of everyone calling him a ‘waste’. This in turn makes Sam come to realise that he’s gotten into this violent lifestyle because he’s a lonely kid with a terrible home life, and ends up supporting him instead of seeing him as her enemy. Even Brewis (Luke Treadway), who is mainly dorky comic relief, gets his own story arc resolution: he may not be from around there, he may awkwardly try to use “urban” speak to fit in, but ultimately his scientific knowledge helps save the day and finally ingratiates him with Moses and Pest.

I would agree with previous critics who said this film was on its way to achieving cult status and would say that everything from the soundtrack, the script, the acting and the effects to the fact that it was executively produced by Edgar Wright, writer director of cult genre-buster favourites Shaun of the Dead and Hot Fuzz means it deserves its 90% score on Rotten Tomatoes (Rotten Tomatoes 2011), and is one film I would recommend to even people who aren’t hardcore sci-fi fans. It’s worth it.

References

Attack The Block, 2011, DVD, Studio Canal UK, London, Directed by Joe Cornish.

Attack The Block, 2011, Rotten Tomatoes, viewed 6th September 2013 <http://www. rottentomatoes.com/m/attack_the_block>

'Attack the Block' Pays Homage to Many Classic Cult Favorites, 2011, Yahoo Movies, viewed 6th September 2013 <http://movies.yahoo.com/news/attack-block-pays-homage-many-classic-cult-favorites-221900444.html>

‘Attack The Block’ Review: A Genre Blending, Cult Classic In The Making, 2011, Slash Film, viewed 6th September 2013 <http://www.slashfilm.com/%E2%80%98attack-the-block%E2%80%99-review-a-genre-blending-cult-classic-in-the-making/>

CULT MOVIE REVIEW: Attack the Block (2011) 2012, Reflections on Cult Film and Classic Television, viewed 6th September 2013 <http://reflectionsonfilmandtelevision.blogspot.co.uk/2012/02/cult-movie-review-attack-block-2011.html>

UK Film Council publishes Statistical Yearbook on UK film 2011, BFI, viewed 6th September 2013 http://industry.bfi.org.uk/15747

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Durgnat Vs Douchet – Fear, Desire and Complicity in 'Psycho'

Raymond Durgnat’s article “Inside Norman Bates” and Jean Douchet’s “Hitch and His Public” are both well written and interesting articles, and share some good points that they approach in very different ways.

In the start of both, each brings up the very first scene of Psycho, the tracking shot into the cheap hotel room where Sam and Marion are having their illicit lunchbreak fling. Durgnat chooses to discuss the “unsatiated sensuality” (Durgnat 1967) of the scene – the desaturated (even for black and white film) look of the settings, the visceral noontime heat, the only half-way nudity of Sam and Marion – and all of this seems to be a theme of Hitchcock’s, the unsatisfied desire, and at the very least a big theme of the movie. Durgnat points out that while we sympathise with the two, we’re more curious to see what they’ll do to be together rather than excited to see everything go smoothly and watch them settle down together. Douchet on the other hand, discusses a similar point from a different angle – that voyeurism is a key theme of Hitchcock’s films, driven to its literal conclusion in the film Rear Window, but very present again in Psycho. She spectates that audience (who are the James Stewart character of Rear Window, wanting to look into where we shouldn’t, wanting to see something dangerous or sexy but also afraid of it) finds nourishment in the opening scene that leads us from the city into the lovers’ hotel room and we see them on the bed, ‘demonstrating a great physical attraction’ (Douchet 1986) but then we also feel frustrated at the lack of conclusion to this encounter and that it can only be satisfied at the end of Janet Leigh’s time in the film. Douchet suggests that in a sick way, her complete nakedness and helplessness as she is stabbed (with a murder weapon of phallic shape, no less) finally satisfies the frustration from that earlier scene, what she describes as a ‘wish fulfilment beyond all hopes” (Douchet 1986.)

This is now where their critical approaches diverge – Durgnat begins to discuss the character of Norman Bates in-depth and then the psychology behind him and other characters, whereas Douchet discusses the storyline in relation to Hitchcock’s style of film-making and themes.

Durgnat talks about how Norman is presented as a sweet, honest naïve ‘country youth’, and that ‘the whole film hinges on his sensitivity and charm – we tend to like him whatever his faults’ (Durgnat 1967.) This representation is important, drawing our attention away from him and towards the more obvious horror elements of the film like the old Victorian house, and the mysterious mother and the remoteness of the motel. Durgnat presses on, postulating that this liking of the sweet, naïve Norman only grows throughout the viewing of the film, suddenly making the viewer question whether they want him to be found out or not. We want the private detective to fail almost, for Norman but we also want her lover and sister to discover what happened to Marion. Durgnat’s point is that we sympathise with these felonious individuals (Marion and Norman) because we are excited by them committing crimes, we want these nice-seeming criminals to get away with these crimes! Then are we, the audience, justifying them as being nice people because we see ourselves that way and could almost justify these crimes to ourselves if we wanted to? Durgnat theorises that Hitchcock is playing a serious practical joke on the audience – making them realise they are complicit in these sins just as much as Marion and Norman are.

Douchet also notices a somewhat religious theme, and explores the storyline after Marion steals the money and drives out of town. She presents a series of theories about the cop that stops Marion, the most interesting being that he is somewhat otherworldly, either Salvation or Retribution, sent to herd her to her doom. We realise as soon as Marion comes to this sinister isolated place, that she will be doomed somehow. She also refers to the audience as complicit in the onscreen crimes, for wanting them to succeed. She then proposes that Hitchcock’s master manipulation of the viewers fears and desires, taking them to the “limits of fear” and leaving them only with blind prayer that Marion’s sister will escape her fate. Both articles are masterful analysis’ of Hitchcock’s work and Psycho in particular and are enduring and relevant even decades after they were written.

References

Durgnat, R, 1967, 'Inside Norman Bates’, Asian and Pacific Migration Journal in R Durgnat (ed.), Films and Feelings, Boston, MIT Press, pp209-20

Douchet, J, 1986, ‘Hitch and His Public’, in Deutelbaum M and L Poague (eds.) A Hitchcock Reader, Iowa State University Press.

Hitchcock, A, 1960, Psycho, DVD, Paramount Home Entertainment.

0 notes

Text

Mad Men Pilot Review: "Smoke Gets in Your Eyes"

The first shot of the Mad Men pilot, “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes” shows a crowded bar, panning over laughing, chatting friends and couples to a man sitting alone. That man is Don Draper, one of the titular Mad Men, or men who work in advertising on Madison Avenue in the 1960s. This first scene makes it clear that this is a very character driven television series. The most important characters this episode focuses on are Don, Peggy Olsen, and Pete Campbell.

Don is the most important character on this show, as of this episode. We only really learn a little about him, but a combination of Matthew Weiner’s clever writing and Jon Hamm’s enigmatic performance makes it seem like we know more. Don is a definitive loner, as that first shot suggests. He isn’t interested in socialising with the office men, and he takes to his office to be alone. He also seems a procrastinator, knowing he has no ideas for a big account pitch but spending the remaining time sleeping with his bohemian artist girlfriend, drinking and sleeping on his office couch. We see that he’s haunted by a war he fought, which seemingly contributes to his semi-nihilistic views on life. He tells this to someone later, "You're born alone and you die alone and this world just drops a bunch of rules on top of you to make you forget those facts. But I never forget. I'm living like there's no tomorrow, because there isn't one."

He keeps a drawer of fresh shirts in his desk, so he can change in his office. In a way, this is just another way Don Draper is about making things up: the image he presents to anyone outside of his office is very polished and together; he asks his new secretary, Peggy, whether his colleague Pete knows he’s sleeping in the office and is relieved when she says no; and he works in advertising, which you later see he’s brilliant at, making something genius up at the last minute of the meeting. He has a complex relationship with women – he’s handsome but doesn’t seem to know what he wants (he has a mistress, a young wife and he starts a flirtation with an intelligent female client in this episode.) Don is a mystery we only really get a glimpse of this episode, making the audience want to come back for the rest.

Peggy and Pete are the two next most interesting characters. Peggy is a naive, Catholic, twenty-something girl who starts as Don’s new secretary. She dresses conservatively, and several characters comment on this as soon as she meets them, all seemingly telling her that she needs to look prettier, wear sexier clothing, and yet is also the subject of the younger men’s sexual harassment. The last of these is Pete, who Don embarrasses when he sticks up for her. The combination of everyone telling her that Don ‘didn’t like his last girl’, ‘he’d like to see [her] ankles’ and this causes her to uncertainly flirt with him, thinking this is what has to happen, but he rebuffs her immediately. She immediately withdraws, humiliated. But there is an understanding there, that she’s ‘not that kind of girl’ and from that, a sort of respect between them.

Peggy is still under confident though, shown through Pete’s arc in this episode. Pete is a young account executive, about to marry a girl with a wealthy father, whom he says he loves. He is at once most privileged out of the three, and yet the most pathetic. He is also extremely ambitious, wanting Don’s job and yet also wanting his approval. Don dislikes his immature fraternity-boy natureand tells him that he’ll never be promoted if he makes a reputation for being unlikable after he embarrasses Peggy with unwanted advances. He steals research given to Don that he rejected for the pitch meeting, and his idea angers the client, proving he’ll never be as good as Don. Even at his bachelor party (which he unsuccessfully attempted getting Don to attend) he harasses a girl to the point where she almost leaves, and he seems unhappy while his friends have fun. Afterwards he drunkenly visits Peggy. Given their earlier interaction, I had thought Peggy would tell him to leave, but she is still naive, and she lets him in because he “had to see her”. Pete is interesting, as he’s had everything given to him and yet he is uncertain, making him sad and petty.

The three main characters of this episode are all struggling with something; Don is lonely, searching for some meaning in his life and relationships; Peggy is naive and unconfident and Pete is uncertain, despite his privilege. This all hopefully will make for some interesting character development down the road, in a well-written, well-acted show such as this.

1 note

·

View note