guttermagazine

9 posts

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

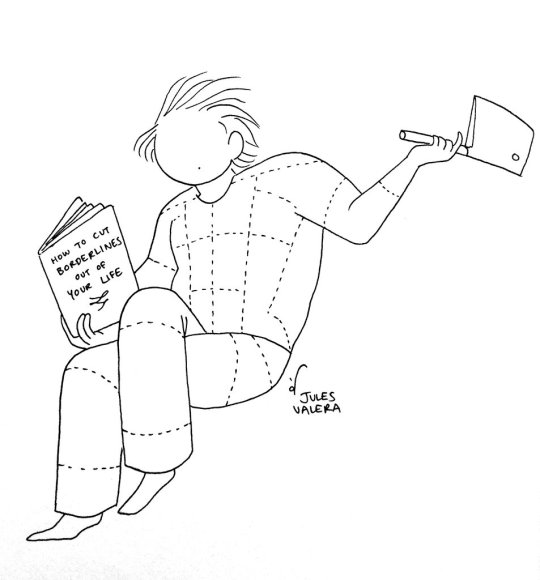

Exclusive Jules Valera Interview

I had the chance to sit down with Jules Valera, autobiographical comic artist, caricaturist, illustrator, animation student, writer, event sketcher and all around good egg. I’d been itching for an interview for a while as I find their work deeply inspiring and admire the way that they’re able to work in a wide variety of styles using a plethora of different media.

Hold onto your hats, chaps, this’ll be a good read!

Rebecca

Hey, Jules! Thanks for taking the time to speak to me. So let’s do this. First question! As a comic artist, how do you feel that you are perceived by the people in your life, the general public and other artists?

Jules

People in my life have responded pretty positively to my work as a comic artist. Comics are pretty cool at the moment and most people have some kind of relationship with them in some form.

I think people generally seem to think it’s cool that you can ‘get away’ with doing comics. The downside seems to be that the prevailing perception of comics is still superhero-exclusive.

Other artists I know seem to have a deep respect and hunger for comics. It’s the perfect fusion of things that artists generally love— story and drawings. Most artists I know, even non-comic artists, seem to get a lot of satisfaction out of comics and respect them as a medium.

Rebecca

So how and why did you end up making comics rather than something else?

Jules

I was a big fan of manga when I was growing up, and I’ve always found comics a very natural way of expressing ideas. A friend who happened to be studying comics studies uncovered some of my comics diaries early in my first year of uni and encouraged me to see the merit in continuing. Through him, I developed an interest in comic studies and particularly in graphic medicine (the overlap of comics and the medical humanities) which had a significant influence on my work.

Rebecca

How did your family react when you told them that you were pursuing comics?

Jules

My parents have both always been interested in comics and graphic novels— my mum read Bretécher cartoons as a child, and my dad is a big fan of Joe Sacco (Palestine, Footnotes in Gaza.) They were both supportive and interested from the get-go and have been ever since.

Rebecca

As an artist, do you ever feel apprehensive about sharing your autobio comics with others?

Jules

No— it can be a powerful means of expressing things that are incredibly difficult to communicate otherwise. The spectacle of it- framing real-life events as a narrative with characters- gives both the artist and reader a degree of distance, while the format- using your own words and pictures- allows you to express yourself without restraint, and allows the reader to fully empathise without feeling the need to ‘say the right thing’ or respond appropriately. In creating and sharing an autobiographical comic, you’re saying, “I’m in control of this story, these events, and how I feel about them, and I’m letting you see into my world.”

Rebecca

Do you feel that you have to exaggerate or slightly twist the events in your autobio comics to draw an audience to your work?

Jules

When I make comics based on true events, I try to focus on my own perspective, feelings, and memories, rather than one hundred percent accuracy and objectivity. In the same way as when retelling a good anecdote, I think some things naturally get edited down so that the timing is a little better or a little more convenient. What you end up remembering and recounting is whatever was important at the time.

Rebecca

Do you feel that comics have to be funny/happy for them to appeal to an audience?

Jules

There’s definitely a market for misery, but I think more than anything else what draws an audience to a comic is relatability. People want to be able to see themselves in comic situations— whether it’s inserting themselves into a superhero narrative, laughing at themselves in a cartoon, or seeing some of their own experiences reflected genuinely in autobio.

Rebecca

Does the way that you feel about the events depicted in your comic before you draw differ from how you feel after you’ve made and shared the comic?

Jules

Often I find that the process of drawing a comic helps provide some objectivity and perspective on my own feelings. Transforming an event into a narrative problem to be solved has always let me see myself a little better— helps me to understand how I actually felt at the time, and how I feel now.

Rebecca

Do you find making autobio comics therapeutic in any way?

Jules

For me, most of my autobio happens very urgently. The immediacy of drawing a comic often replaces a more self-destructive compulsion, and the emotion that then goes into those drawings and words is often something that I wouldn’t be able to express any other way. I think therapeutic might be the wrong word. If I don’t do the work unravelling issues and coming to terms with them with the help of a therapist then I know I can’t produce anything much of worth (if anything at all)— but comics provide me with context and allow me to see my own feelings objectively, transforming events and emotions into narrative problems to be resolved and presented to an audience in some way.

Rebecca

In making comics that people are able to relate to and engage with, do you feel as if you’re part of a community?

Jules

I think community can be a bit of a double edged sword. There’s the very immediate satisfaction and sense of validation that comes from people sharing your experiences and relating to your work, which I think is a very good and necessary thing. It comes with the burden of other people’s expectations, however, and I think the particular danger of your work being relatable to many people, especially when you do autobio, is that you become very available to them. I’ve been approached by strangers who felt like they knew me through my work and started very personal, overly familiar conversations with me because of it.

Rebecca

Autobio comics have been criticised for being too self-indulgent and as being of less worth than a fictional story such as those depicted in graphic novels. What are your thoughts on this?

Jules

I feel strongly that good stories, factual or fictional, always thrive on authenticity, and I believe that authenticity comes from people’s ability to transform their own experiences into a narrative. You don’t need to look far into autobiographical comics to find this happening- for example, in the works of Lynda Barry, Alison Bechdel, Marjane Satrapi, where a life story becomes a deeply intriguing story in its own right.

Rebecca

Do you think that autobio comics are important for not only a reader but also the artist creating them?

Jules

I think there’s great importance in letting people narrate their own experiences. It’s often the case that when someone is experiencing illness, trauma, grief, any number of life experiences, they’re forced to abdicate some control over to other people— in my case, writing about mental health, control of my life and experiences were often handed over to my family, my doctors, and anyone else with an opinion. Writing about it put me back in control over my own history and gave me an outlet to work out what I felt and experienced without having to put anyone else first.

Rebecca

Has reading a comic (be it autobio or not) ever helped you get through a difficult time?

Jules

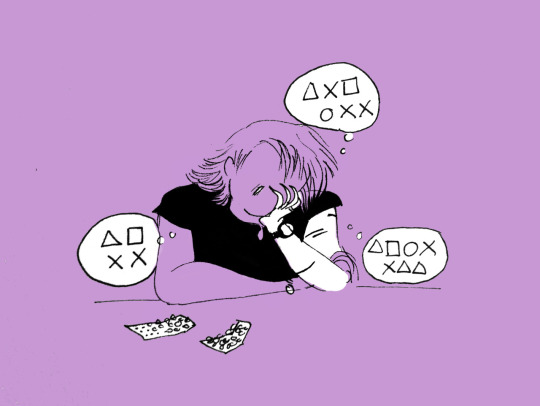

Definitely. I had a friend who could provide a comic for almost any event or occasion, and he gave me Glyn Dillon’s The Nao of Brown, which was a big help to me when I was struggling with obsessive compulsive disorder (the comic is fictional but loosely based on Dillon’s wife’s experience with OCD.) Darryl Cunningham’s Psychiatric Tales, a frank, straightforward, and kindly graphic novel about experiences of working as a psychiatric nurse, was also a great comfort when I was unwell. Saki Hiwatari’s Please Save My Earth was incredibly formative in giving me a story to relate to as a teenager experiencing dysphoria, as the manga deals with themes of identity, gender, and sexuality through the story vector of reincarnation.

Rebecca

Do you feel that the impact left on its audience by a comic differs to that of a novel, film or other form of art?

Jules

Comics are still considered, to some degree, to be a ‘junk’ art form. I think this can be a very good thing for comics, though— I appreciate that there’s still a sort of unpretentiousness to the reading of comics, and I think this allows readers to be moved and affected by them almost unconsciously in a way that’s different to the more lofty experiences of reading a novel or watching a film.

Rebecca

What are a couple of your favourite comics that you would recommend to readers, and do they differ from comics that you would recommend to aspiring comic artists?

Jules

For readers and artists alike, I would recommend anything by Chris Ware (particularly his ACME Novelty Library series, as well as the massive Building Stories) as he really does push the boundaries of what a ‘comic’ can be. Glyn Dillon’s The Nao of Brown is another favourite, with a more conventional structure, beautiful art, and a powerful, loving story. Lynda Barry’s cartoons are excellent (What It Is is a good one), and Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi should be required reading for most comics enthusiasts. I also love anything by Michael DeForge (Ant Colony). For aspiring comic artists, I’d say just read whatever appeals to you, art-wise or story-wise. New artists are constantly reinventing the medium.

Rebecca

What is your outlook on what it will be like to be a professional artist after leaving art school?

Jules

I ask my Magic 8 Ball this question all the time.

Rebecca

As an artist, do you worry about financial security?

Jules

Constantly.

Rebecca

Do/will you have to rely on other forms of income such as Patreon or a part-time job to be able to create comics?

Jules

I freelance doing commissions and bits and pieces of design work currently, which is more or less sustaining me for the time being, but after graduation I’ll most likely need a part-time job of some description. I hope to have a Patreon for comics and art up and running in the next year!

Rebecca

How has the ability to use the internet to share your work affected your career as a comic artist?

Jules

The ability to use the internet has been absolutely crucial in my career as a comic artist. The vast majority of acquaintances, friends, and collaborators I’ve met in comics, I’ve primarily met through Twitter initially. I think the internet, for better or for worse, puts artists all on a somewhat level playing field— it doesn’t cost anything more than the price of an internet connection to publish your work, advertise yourself, network with other artists, gain an audience, and sell things, all online. The value of internet relationships is massive for providing everything from support and resources to literal couches in countries across the world.

Rebecca

Would you ever want to work for a publisher or would you rather self-publish your work?

Jules

I think both have their merits, but I don’t have any experience with either so I’m unsure of the benefits and downsides of both. I have friends who’ve started their own small press imprints, which interests me a lot.

Rebecca

Have you ever taken part in a collective comic anthology? Do you feel like you gained anything from working with others?

Jules

I’ve been published in anthologies a few times— local comics collectives and fanzines mostly. The pressure of a deadline and the thrill of seeing your work published as well as the social aspect of going to launches and promoting the work are all good things I think. I would love to do more practical collaborative work with other artists in the future.

Rebecca

What is your opinion on manga – is it the same as reading a Western comic?

Jules

I think manga follows a different set of rules based on an entirely different history and storytelling tradition from Western comics. Personally, I was drawn to manga when I was growing up because the artwork appealed to me more, but also because the stories in shōjo manga felt more contemplative, with thoughtful pauses visualised in consecutive black pages, empty speech bubbles, metaphorical flowers blooming, et cetera. There was an emotional focus that I found Western mainstream comics largely lacked. My experience of reading manga was, and still is, very different because of that sense of emotional timing.

Rebecca

Thanks so much for your time!

You can find Jules’ work online on their twitter and portfolio site

https://twitter.com/lieabed https://www.julesvalera.daportfolio.com

0 notes

Text

Autobio comics – important or self-indulgent?

Autobiographical comics, as you may have figured out, are comics drawn by the artist that depict events of their own lives. Autobio comics are popular with some comic fans because of their relatability and realness, but have also been heavily criticised and shunned by other comic fans.

Using Twitter, Sophia Foster-Dimino reached out to the Titter comic community to ask what it was specifically that people didn’t like about autobio comics and received a huge response.

Julia Gfrörer responded, ‘I get annoyed when they’re braggy or approval seeking. Anybody who needs to be the hero has no business writing autobio’. Some autobio comics unfortunately do portray a hero complex and this has definitely fed the stigma of self-indulgence, and yet, the point of autobio is not to be a hero, or even an everyday hero, but to be a human being; to be flawed.

(Above: Muggy Ebes - Lucie Ebrey)

Many of the responses brought up the issue of gender. Apparently autobio comics made by men are perceived by women as being a showcase for their male privilege while comics made by women are perceived by men as being shallow. Twitter user, ~Slime Dog concluded that ‘the only time [they] don’t like autobio is when they’re by boring white straight dudes [because] they’re boring and unrelatable’. Unfortunately, issues of race, sexuality and gender are often brought up in toxic and unhealthy ways when discussing autobio. It can be easy to feel as if you are not represented, yet are expected to be able to relate to the comic; however, just because one individual can’t relate to one autobio comic shouldn’t mean that the genre deserves to be criticised on the whole. Criticising an artist because of their gender, sexuality and race (all at once, in the above example) extremely prejudiced, and yet, comments such as this were abundant in the findings.

One of the greatest strengths of autobio is that anyone can be represented because of the fact that so many different people from all walks of life create autobio comics and as a last resort, you can represent yourself and create your own if you want to. There are many autobio comics created by the LGBTQ and POC communities. Because of this, it could be said that it is invalid and inappropriate to criticise autobio comics because of their protagonist, so to speak, unless the material is inherently sexist, racist, transphobic, homophobic or offensive in any way.

Another criticism of autobio comics is that they’re a gateway for younger or more inexperienced artists to take a dip into making comics, because subject material is so easy to find. You can create a comic about literally anything that happened to you ever and expect people to read and appreciate it. This is definitely self-indulgent but perhaps that is no bad thing, as reflected in the opinion of Sarah Glidden, ‘art is kind of self-indulgent? But who cares? Someone is communicating something. Let them do it.’

(Above: Safe Spaces - Schnumn)

And so, this raises the question, is it OK to communicate when you have nothing of importance to say? I would argue yes. Freedom of speech. I would also add that the more you practice communication, the better you will become at communicating, and perhaps, in time, you will have more meaningful things to say. Even with autobio comics, developing a narrative takes time.

(Above: Choice - Schnumn)

I interviewed comic artist, Jules Valera and asked for their opinion, ‘I feel strongly that good stories, factual or fictional, always thrive on authenticity, and I believe that authenticity comes from people’s ability to transform their own experiences into a narrative’. Thus, someone’s life story can become a deeply intriguing story in its own right, but requires skilful execution.

I asked Jules for their opinion on whether autobio comics are important for not only a reader but also the artist creating them,

‘I think there’s great importance in letting people narrate their own experiences. It’s often the case that when someone is experiencing illness, trauma, grief, any number of life experiences, they’re forced to abdicate some control over to other people— in my case, writing about mental health, control of my life and experiences were often handed over to my family, my doctors, and anyone else with an opinion. Writing about it put me back in control over my own history and gave me an outlet to work out what I felt and experienced without having to put anyone else first.’

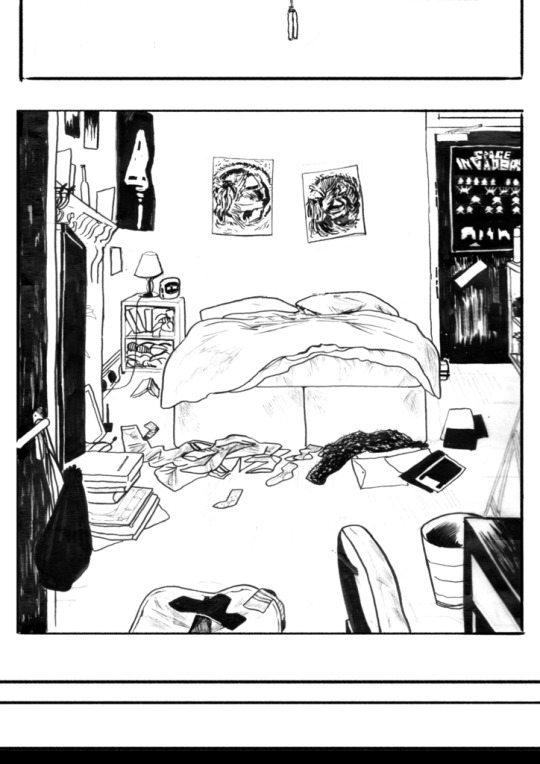

(Above: In Your Shadow - Jules Valera)

When reading some autobio comics, you can find yourself wondering what the point of that was, or thinking something along the lines of, yes OK, that is relatable, but does it need to be a comic? Have you created this for the sake of art and expression or for the retweets? On the other hand, autobio comics done well convey something bigger and more important than the self. The self is just a gateway into an experience, feeling or observation. Autobio comics done well convey the human experience in its purest form, and that is something that we can all relate to.

0 notes

Text

Starting with superheroes: comics as apowerful tool of communication

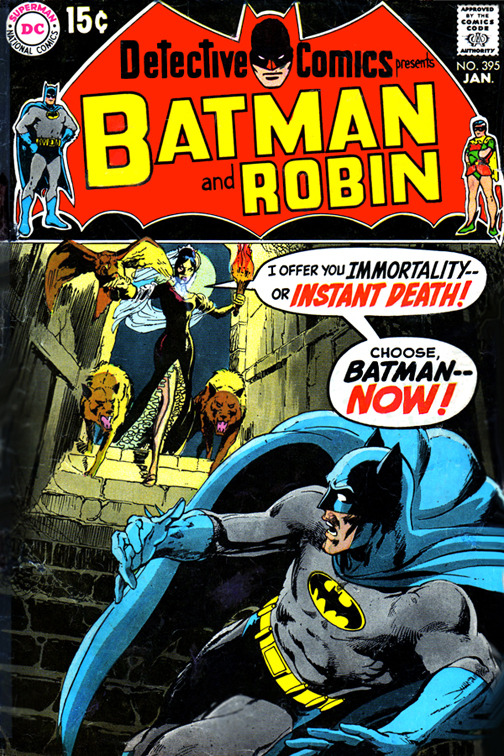

When we think of comics, most of us instantly recall American classics such as Superman and Batman, probably rescuing a defenceless damsel in distress or kicking some bad guy’s butt. This form of comic first gained popularity after the 1938 publication of Action Comics featuring the debut of Superman, although the comic form can be traced to much further in the past.

Since their conception, comics have fought to become a respected form of communication and genre of literature, with conflicting response. There are many who believe that comics are solely meant for children, and others that believe that even children should not read them as they encourage them to turn away from the reading of novels and of classic literature (apparently, it’s inconceivable that you can enjoy both). Carol L. Tilley, a professor of library and information science in Illinois has discussed this, "A lot of the criticism of comics and comic books come from people who think that kids are just looking at the pictures and not putting them together with the words. Some kids, yes. But you could easily make some of the same criticisms of picture books - that kids are just looking at pictures, and not at the words."

Contrary to these beliefs, it has been proven that comics have helped to improve literacy in children and adults, both now and in the past. In the second world war, one of the many problems the military faced was that there was a large amount of illiterate citizens who were suddenly expected to be able to operate complex machinery. Comics played the role of communicating instructions to soldiers while also slowly teaching them to read. Today, comics are used frequently to teach children with dyslexia and other learning difficulties, thus they are not only tools of communication, but also agents of communication that allow others to learn how to communicate through the written word.

It is interesting to note that comics were originally meant for adults, not children. From political strips in newspapers to Detective Comics (who later became DC) with their violent heroes and sexual heroines, it could seem difficult to believe that anyone would want to pass on the material depicted within comics to children, but despite the above, these superheroes have acted as positive role models and provided escapism for both children and adults since their inception.

Batman in particular was an important role model for the American nation. Unlike Superman, Batman lacks any form of super power, instead relying on his human strength, inventions and his mind to fight crime. Batman was an inspiration because he felt like a more attainable hero while Superman’s powers were impossible, but this is not to say that Superman wasn’t important. Both heroes strived to defeat evildoers at any cost, both heroes defended the weak and upheld the good and both heroes were an ideal that was pleasant to believe in.

Comics have played a vital role in America since their beginnings but particularly around the second world war. They were compact and cheap; easy to carry around and trade, and their simple speech balloons and easy to read fonts made them accessible to those of poor reading, not to mention the fact that the stories were of a pictorial nature which made them accessible to the illiterate. In terms of communication, they conveyed powerful and complex ideas in simplistic ways to allow all ages and levels of learning to understand them.

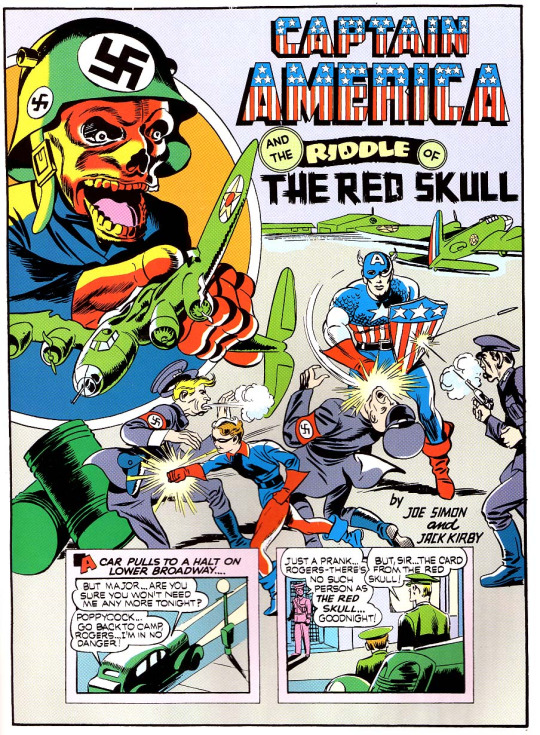

The form of comics and their influence on the youth especially were taken advantage of during the war. While at first, comic publishers and writers were reluctant to get involved with the war effort – reflecting the mind-set of the nation at the time – but soon, heroes such as Shield Man and Captain America emerged in red, white and blue costumes and were shown to be fighting the Nazis. Even a Nazi villain, Red Skull, was created. Superman and Batman, while not shown to be fighting Nazis, were used to promote war bonds and later, The Red Cross. By this point, their influence on the nation was huge and the campaigns were successful.

Soon, America was in total war. Comics still served as a form of escapism, but in a different way. While before their heroes had been fighting evildoers, their enemies were now the very tangible and threatening Nazis, whose defeat at the hands of the heroes was critical for the morale of American youth at the time. The creators of the characters and publishers belonged to a group called the Writers’ War Board who were privately run but received government funding. While the creators never lost control over how the public saw their heroes, the WWB had control as to how the villains were portrayed. The Nazis and those who supported them appeared as being twisted and deformed next to the handsome and well-sculpted heroes. While this was important to the war effort, it could be argued that these portrayals of other nations infected the minds of the youth at the time, leading to generations of racism.

Comics have also been used in textbooks to make topics that may be perceived to be monotonous or boring interesting. A good example of this is the Horrible Histories series, a British collection of books in which historical figures and events are turned into comics alongside text to make the subject more light-hearted and funny, therefore more significant and memorable to the reader.

As a form of communication, it can be said that comics are an extremely powerful format. They have the power to spread ideas to all ages and even transcend language as their pictures can fill in the gaps that not being able to read the words might leave. They can be used as a method of propaganda and be a method of sending ideas, be they good or bad. Comic heroes can instil hope, bring people together and even make people realise their mistakes. Comics are ideas given character; ideas made real and human. The combination of visuals and text are its strength and it is difficult to imagine another form of communication that has that power.

0 notes

Text

Quick tips on tackling loneliness as an artist

Listen to podcasts/ artist vlogs while you work. They’re great for boosting inspiration and motivation whilst making you feel like there’s someone else in the room

Make the effort to go to a local life drawing group. It’ll be good for you and good for your art

Make artist friends, online or otherwise, and collaborate regularly. You could even do something as simple as streaming together on Twitch or YouTube.

Engage with the online art community. Look at other people’s art, especially if it’s similar to yours. Leave lots of comments.

Join an online DnD session (psst, that stands for Dungeons and Dragons). Yeah, I get it, Roleplay isn’t everyone’s bag, but it’s great for improving your storytelling and character design skills while also being fun. Just try it before you snub it, OK?

Get some plants and/or a pet (if you can afford to/have the space and time to care for it. Do not get a pet without considering it THOROUGHLY).

0 notes

Text

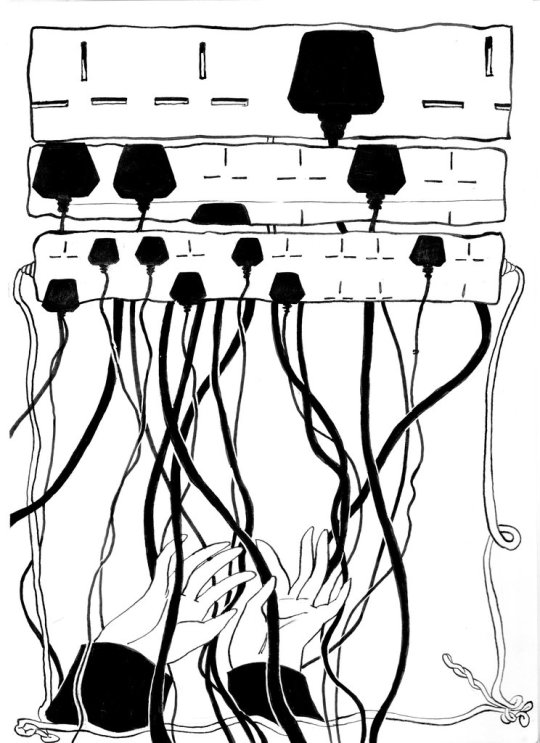

Problems of the creative shut-in

Anyone who creates, by default, has to spend a large portion of time alone in order to be able to get anything done. Creatives mostly prioritise the honing of their craft and project progression over fun, often out of necessity rather than choice.

The creative field is an incredibly competitive one, and with the rise of the Internet and digital learning resources such as Pluralsight and Ctrl+Paint as well as art accessibility, more people are being inspired to get creative. While this is undoubtedly a good thing, it unfortunately means that there are more people than ever applying to jobs in the creative industry.

For example, any animator will be able to tell you that the all-work-and-no-play mentality comes with the territory, not only because it is such a pain staking and time consuming task but also because it is such a competitive industry. You have to be the best to be hired, and you can’t be the best without some hard ass work.

But creative burnout is definitely an issue that most artists face at some point and it can be easy for artists to come to resent the projects that they once loved when they are forcing themselves to work on them all the time. It’s like that old saying goes: no TV and no beer make Homer something something.

Go crazy? Maybe not quite. But taking breaks and having fun is vital to the creative process. Unfortunately, sleepless nights and working until the point of exhaustion seem to be not just an unfortunate by-product of the creative lifestyle, but actually an expectation of anyone who wants to be taken seriously as an artist or designer.

The distinguished Feng Zhu of FZD Design recounted in his YouTube vlogs that in order for him to be successful, especially as a student, he felt that he had to be constantly creating and developing his skills every waking hour of the day until he finally landed a job, at which point he decided to stick strictly to the 9-5 work regime, in order to be allowed to have a social life and relaxation time.

Unfortunately, taking regular breaks and fulfilling our social needs is easier said than done when you’re trying to get something done. Time spent away from work can result in feelings of intense guilt. Before you know it, you find yourself in a position where you’re ‘taking a break’ but constantly worrying about what you’re not doing. This isn’t really taking a break, it’s just a stressful limbo where you’re constantly aware of how far behind you’re falling and how difficult the struggle will be to catch up.

But breaks are important, nonetheless and everyone, have to take them, artists and non-creatives alike. Leave the room. Do something else, and most importantly, accept that you’re taking a break and that it’s OK to do that. Accept that now is not the time to be thinking about work and set yourself a time or a day to return to what you were doing. Structure your me time in a way that makes sense. Structure your work time in a way that ensures you know what you’re doing. Make to-do lists, if that’s the kind of thing that helps you. Most of all, hold onto your drive and remember what it is that you love about what you do.

0 notes

Text

Why aren’t comics cool?

(I mean, they so totally are… but for the sake of discussion, let’s dig a little deeper…)

It’s no secret that in the past, comics have been considered to be utterly uncool; something that only nerds enjoy. Nerds are often frowned upon by the ‘cooler’ members of our Western society. It’s difficult to narrow down what a nerd is exactly in formal terms, as it’s such a colloquial term, but it’s definitely a pejorative term, describing a person who typically lacks social skills, preferring to spend their time studying, reading comics or playing video games. Typical characteristics of a stereotypical nerd are obsessive behaviour and a preference to spend time indoors with their various hobbies than in ‘the real world’ interacting with others; however, this is a dated idea and does not necessarily apply to today’s modern nerds.

The Internet has greatly affected the way that everyone lives their lives – nerds included. While it may seem that they may be spending all their time indoors alone, the lone nerd may not actually be lonely at all. Online multiplayer games and even online Dungeons and Dragons sessions are a popular pass-time for the common nerd. They enjoy discussions that take place with like-minded individuals whilst not having to sacrifice the comfort and safety of their own home.

The fact is that today, it is far more acceptable to be a nerd. Nerd culture has even been celebrated, in part, thanks to the help of Hollywood and its superhero films. You don’t have to be a diehard Marvel fan to enjoy the Spiderman films (…the newer ones, anyway) and these films are a common ground between the nerds and their cooler counterparts. Nerd culture is an integral part of pop culture, which is becoming more and more mainstream, especially amongst millennials and 90s kids but even beyond. In its own strange way, being a nerd is now considered to be a strange form of… cool.

But what even is coolness? According to Bruce Mao’s Incomplete Manifesto for Growth (1988), ‘Cool is conservative fear, dressed in black.’ This statement has come under a great deal of scrutiny, but it does make sense. If what is cool equates to what is popular, then doesn’t everyone who is cool simply follow the crowd? Is that not conservative fear? Yes, but there’s more to being cool than fashion and keeping up with trends. Perhaps what is truly cool is not caring what others think, but enjoying what you enjoy anyway and not being shy about it.

The archetype of the badass is undeniably cool. It’s cool to break the rules and not get caught. It’s cool to be chill and reserved, while being respected. Maybe that’s why Batman is often considered the coolest of all the superheroes. He’s gritty and dark and doesn’t rely on fantastical powers to get shit done.

So, if the characters in comics are cool? What has made the medium as a whole so uncool in the past? Perhaps what really defines being uncool, is being a shut-in. Being someone who doesn’t spend any of their time interacting with others in meaningful ways and building social skills and friendships. This would explain why, especially in the past, comic readers and video game players were chastised by their family and mocked by their peers. The stigma that being a comic fan equates to being a hermit is one that has stuck, but in the modern era, it is slowly being deconstructed.

Another problem that comics have had in the past is that many of them catered very specifically to fans of science fiction. Sci-fi comics such as 2000AD and Star Trek had far more complex storylines than most other forms of entertainment at the time. They discussed paranormal activities and parallel worlds, often using complicated jargon to tell their stories. This made them less accessible to anyone who wasn’t smart, or a nerd. This is less of a problem now, as comics are a medium that span hundreds of different genres and are a lot more relatable, but it could definitely be said that this is largely why comics were considered to be nerdy and uncool; a stigma which stayed with them for decades even to the present day.

0 notes

Text

Recommended Webcomics

Check out these gems!

Tapastic.com/series/Purgatory Mspaintadventures.com Thegamercat.com Avasdemon.com Muggyebes.tumblr.com Sarahcanderson.com Webcomicname.com Poorlydrawnlines.com Explosm.net

0 notes

Text

Where are all the comic fans?

From three-panel newspaper strips to graphic novels, most of us have encountered a comic in some form at least once in our lives, and yet, it seems that most of us keep relatively quiet about it, especially when compared with how much we discuss other media. Do we just not care that much about comics, or could it be something else?

It’s a given that some people genuinely really just don’t care about comics. At all. Fair enough, but there are hundreds of thousands of comic fans out there – right? Where are they all?

Kevin Drum, political blogger for Mother Jones, estimated that a mere two percent of millennials read comic books in 2014. That’s a shockingly small percentage considering that millennials often get a bad rap for allegedly being lazy, comic book reading, video game playing couch potatoes (although admittedly, I am all of those things. Maybe it’s true).

But his data is flawed. It doesn’t cover the sale of comics online and in used book stores; neither does it take into account the sales of smaller comic publishers. But the data’s true flaw lies in the fact that it reduces reading comics to buying them.

Comics, as with a great many other things, are no longer restricted to the printed form and are available online for free. Creators are able to cut out the middle-man by publishing their work on the Internet using blogs such as Wordpress and Tumblr or sites specifically made with comics in mind such as Tapastic.

Webcomics are incredibly popular. They don’t require you to carry around anything other than a device which can connect to the internet, which you were probably already carrying around, you can blast through them relatively quickly and if you’re reading them on a phone, even in a public place, no-one will ever know.

Most webcomics have a regular update schedule which means you don’t have a wait a month or a year (although this is not always the case… Homestuck, I’m looking at you!) or however long for the next part to be released, and in the time that you are waiting, you can join in with some online discussion, which can be pretty fun and lead to the making of new friendships. Comics on the whole have a pretty broad community, sure, but within that community dwell a multitude of smaller communities dedicated to particular fandoms so it’s easy to find something to talk about or to speculate on what happens next in your favourite comic (beware of spoilers if you’ve not fully caught up yet).

Debatably, one of the most important aspects of webcomics is that they’re easy to share. With the simple click of a button (or, a few buttons, depending on what website or app you’re using… or no buttons, if you’re using a finger …does tapping something on a screen count as pressing a button?) you can share a whole comic with a friend or a whole host of people online. And then, if your pals read it, you’ll probably just talk about it online over whatever platform you used to share it in the first place. And so, perhaps one of the main reasons why we don’t hear people talking about comics so much is because the discussion takes place online.

There are so many places to talk about comics online and they’re easy to find with a simple Google search. In theory, online comic communities provide a safe space for fans to discuss their interest without the fear of being judged, although in reality, it’s not quite so simple. From comic discussion boards such as CBR Community and The Outhousers to comic subreddits, comic elitism is definitely a thing. Beware and possibly reconsider if you’re a casual fan because if you haven’t read every single issue of Batman since its inception, whatever you have to say is probably wrong and oh, boy, you will be made to know it.

But speaking of casual comic fans, so many people read comics and don’t even know it. Trigger warning: now is the part where I talk about memes but bear with me (if you can stand to) because this is actually relevant.

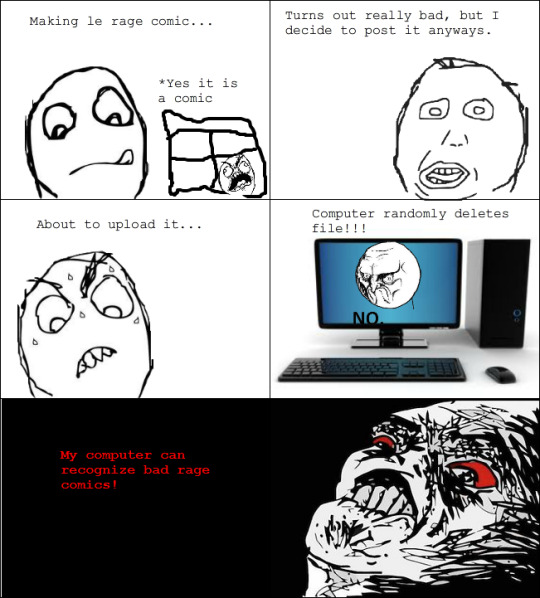

From their inception in 2008 on 4chan until around 2011 when their popularity started to decline, Rage Comics were all the rage (pun intended. Obviously). If you don’t know what a Rage Comic is, you’ve clearly been living under a rock for quite some time. I recommend not only searching up what Rage Comics are, but also a great many other important and culturally relevant modern things such as dabbing and Harambe. Anyway, now that we’re all on the same page, it seems strange to think of Rage Comics as being comics because first and foremost, they’re a meme. But comics and memes are by no means mutually exclusive.

Rage Comics became so popular that people would talk about them and (rather annoyingly) quote them in real life all the time. Eventually, everyone wanted to make their own, resulting in Rage Comic creators such as Dan Awesome’s Ragemaker Site and the Memebase Ragebuilder.

The prospect of non-artist adults wanting to make comics is incredibly interesting. Children draw comics because they are able to be creative without fear of judgment and they are allowed to be interested in comics and cartoons. Artists make comics because that’s what they do. It’s what they love. It’s what they’ve sent years learning how to do through gritty trial and error; through many sleepless nights and tears. But non-artist adults making comics. That’s new. Was it just because Rage Comics were so popular? Did they just want a slice of the meme pie? Maybe, but more than that, it was because anyone could make them and everyone has a story to tell.

Rage comics are a very crude form of autobio comics. They depict everyday experiences that pretty much everyone can relate to, and by their very nature, mostly look the same, using pre-made templates of characters. All one needs to do to create a Rage comic is to have an idea and use a Rage Comic builder. Pretty easy. It makes you wonder why, if so many people would make comics when it was easy, doesn’t everyone make comics all the time?

Largely because it is deemed acceptable to create and share memes. Not only acceptable, but cool. Everyone wants to be a memelord. But creating comics from scratch, dedicating large portions of your life to drawing cartoons? Nah, that’s for nerds. Screw that. So you could argue that the only real difference between making certain kinds of memes (because it’s not just Rage Comics, basically any meme with more than one image could be reductively defined as a comic) and comics is the amount of effort put into them.

I mean, obviously there’s more to it than that, but it’s a pretty interesting comparison. Without comics, would we have memes? Probably. Nothing can stop the meme train. Even ‘real’ comics have been turned into memes. As an example, Sarah Anderson comics have a huge following and people share them all the time, especially on Facebook, because they’re so relatable. People will think ‘that’s so me!’ and share it. And then they go and read more of them because there are so many of them and they’re all so relatable while being quick to read but also being good time-fillers. But most of the people who read her work probably don’t consider themselves to be comic fans – even though they totally are.

It’s pretty cool that people can read and share comics without even really thinking of them as being comics. It’s thanks to things like this that the stigma of comics as being nerdy (the bad kind of nerdy, not the good kind, by which I mean the fashionista hipster bullshit ‘I’m a nerdy girl’ kind of nerd, if that can even be deemed good at all) is slowly disappearing. But what’s equally as cool is that it basically means that comic fans haven’t disappeared at all. They are everywhere – in disguise.

0 notes

Text

Welcome to the best of both worlds!

Mmmmm, comics. The delightful blend between novels and visual art. The story told with both images and words. Here on this blog, I’m taking a look at the medium that has taken the world by storm and against harsh criticism, finally seems to be earning the respect that it deserves as an art form and valid means of communication.

Whether you’re an artist who makes comics, an artist in general, a comic fan or whether you’ve never read a comic in your life (which I doubt!), there’s tons of intriguing content here. Maybe you don’t even like comics; maybe you believe that they’re a waste of time. Pray thee, read further.

All in all, this tiny blog is pretty packed with comic goodness which I sincerely hope you enjoy.

Rebecca Ollerton, Editor [email protected]

0 notes