Slightly passionate, slightly obsessive, this blog serves to catalog every photo of Old New York City I can find. Explore New York City by decade, search for a specific person or place, or click here to view random post

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

Teenagers on the Bank of the Frio Canyon River: May, 1973

These photos were commissioned by the Environmental Protection Agency as part of the DOCUMERICA: The Environmental Protection Agency's Program to Photographically Document Subjects of Environmental Concern, 1972-1977.

From The US National Archives: Source

#1970s#70s#1973#Texas#Teenagers#Hippies#Pot#Marijuana#Kissing#Kiss#Girls#Women#Documerica#epa#Frio Canyon River#May#US National Archives#US Archives#smoking

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

1990s NYC Punks

Uploaded by Diego Montoya to Flickr. That’s ABC no Rio btw.

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

Members of the Cree Tribe

On the roof of the McAlpin Hotel in New York City in 1913. Byron Company

From the Collection of the Museum of the City of New York.

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

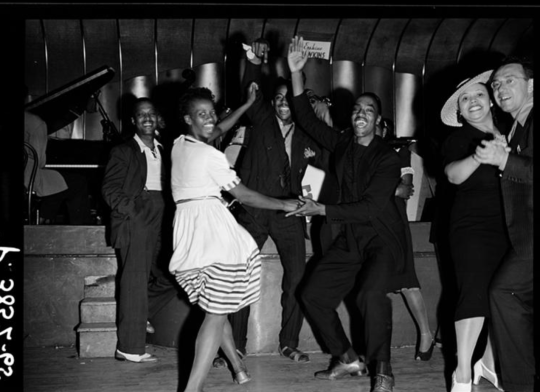

Jitterbugging in Harlem

From the Sid Grossman submission to the Federal Art Project of 1939. From the Collection of the Museum of the City of New York.

#30s#1939#Federal Art Project#Harlem#New York City#Vintage New York City#Sid Grossman#poc#vintage poc

261 notes

·

View notes

Text

So long, sweet summer.

Part of the Federal Art Project submission by Andrew Herman. From The Collection of The City of New York. 1939.

74 notes

·

View notes

Photo

1933 view from the Empire State Building toward the northeast.

Associated Press photo.

158 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A 1933 view toward the Empire State Building from 41st Street & Fifth Avenue.

Photo from the Postcards from old New York facebook page.

171 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bergdorf Goodman, 1979

448 notes

·

View notes

Text

The First Artist’s Loft Building

This blog is my personal memorial to a lost time in New York City. With each long-form post, I’m trying to recreate a scene or experience which is gone forever. This semester I’m taking an amazing class called “New Perspectives on American Art for the 21st Century”, taught by Dr. Joyce Polistena at Pratt. Over the course of the semester, she has mentioned that many of the painters we’re learning about lived on 10th Street. This post will serve as an attempt to resurrect the Tenth Street Artist Studios, the first artist lofts.

(Berenice Abbott, Tenth Street Artist Studios, 1938, From the Collection of the Museum of the City of New York.)

The Tenth Street Studio Building was erected in 1857. It was funded by a businessman named James Boorman Johnston. Johnston hired architect Richard Morris Hunt to design the first building purpose-made for artists. The units were attainable only to established artists due to the fact that studios, some with attached bedrooms, rented for between $200 and $400 dollars per year. The photo below is of Richard Morris Hunt’s space in The Tenth Street Studio building. Pictured are the desks of some of his students in the architecture school he eventually opened in the building. (Source)

The building was designed around its central communal gallery, illuminated with ambient light from the glass skylight ceiling. Sprawling outward from the center were the private studios of some of the greatest American artists of all time. In this digitized directory from 1876, we can recognize plenty of the residents.

(Source: NYPL/Google)

This photo taken in 1866 by S. Beer shows Worthington Whittredges’ studio with many other artists inside! Shown are William H. Beard, John George Brown, John W. Casilear, Sanford Robinson Gifford, Regis F. Gignoux, Seymour J. Guy, William M. Hart, Edward L. Henry, Richard W. Hubbard, Thomas Le Clear, Jervis McEntee, John F. Weir and Whittredge. (Source)

The building was not only a conveniently designed space to paint but the communal gallery quickly became the epicenter of exhibitions in New York City. In 1859, Frederic Edwin Church exhibited his 10-foot panoramic painting, The Heart of The Andes in Tenth Street’s central space. (Wikimedia Commons)

“The installation of the work was as unique as its dimension and detail. There is no record of the appearance or arrangement of the Studio Building exhibit. It has been widely claimed, although probably falsely, that the room was decorated with palm fronds and that gaslights with silver reflectors were used to illuminate the painting. More certain is that the painting's casement-window–like "frame" had a breadth of fourteen feet and a height of almost thirteen, which further imposed the painting upon the viewer. It was likely made of brown chestnut, a departure from the prevailing gilt frame. The base of the edifice stood on the ground, ensuring that the landscape's horizon would be displayed at the viewer's eye level. Drawn curtains were fitted, creating the sense of a view out a window. A skylight directed at the canvas heightened the perception that the painting was illuminated from within, as did the dark fabrics draped on the studio walls to absorb light. Opera glasses were provided to patrons to allow examination of the landscape's details, and may have been necessary to satisfactorily view the painting at all, given the crowding in the exhibition room” - Avery, 1986.

This “grand opening” of the building predicted a decade of prosperity for the studios. The Tenth Street Studios transformed mere painters into true artist-entrepreneurs. After Church’s exhibition was over, he sold the painting to a private buyer but reserved exhibition rights. (Heart of the Andes is now part of the permanent collection of The Met) Frederic Edwin Church transcended his role as ‘mere painter’ into ‘savvy businessman’. The Studios brought the artists into direct contact with their customers and potential-patrons.

The image above is an illustration of a reception at Tenth Street in 1869. (Source)

Visiting The Tenth Street Studios was as much an artistic affair as it was a social event. There are numerous newspaper articles from the time period, pouring over the elaborate and vast details of the space. On January 19th, 1859, this article was published in The New York Times:

“Artists’ Reception in the Tenth-Street Studio. - Brilliant Assemblage.

There are few things more delightful, as Mr. Micawber says of a deviled turkey’s leg, than an artist’s reception. It is one of the institutions that have naturally sprung up quite promiscuously and naturally within the past three of four years, and they have been productive of a vast deal of benent both to Society and Art. There are two of these institutions. One is composed of an Association of Fifty Artists who give their reception and exhibit their “works” at the same time in the large room of Dodworth’s Dancing Academy ; the other is more exclusive, and is composed solely of the artists who inhabit the cloisters of the studio in Tenth-Street. The Dodworthians held their first reception for the season a few weeks since and the artists of The Studio held theirs last evening, in the large exhibition-room of the Eccaleobion of the Fine Arts. No pictures or works of art of an kind were admitted, except the productions of the artists of the Studio, and a most brilliant and attractive display they made. The only drawback to the pleasure of the exhibition was the trifling one of not being able to see any of the works exhibited. The great charm, however, of these receptions is not the pictures, nor the sculpture, nor the drawings, but the company. You find yourself, on entering the rooms, if you succeed in entering them, in the midst of a brilliant assemblage of youth, beauty, and fashion; of men worth knowing and women worth seeing ; and being hemmed in on all sides by orbicular spreads of brocade and velvet, you stand still, with your hat above your head, or suffer yourself to be swayed hither and thither by the pressure of the crowd. You catch glimpses of gilt frames in the distance, and now and then you find yourself thrust against a white but unresisting object, which you discover, on turning your head, to be a hideous group of Italian peasants in marble. You know there are charming pictures on the walls, lovely landscapes by Hubbard and Gifford and Quicy Thorndyke and Regis Gignoux, and Suydam and others ; you know there are groups of game by Hays and portraits by Osgood. But what’s the use? You cannot see them. Nobody sees them. But everybody sees everybody and there’s the delight of it. The ladies exhibit their their marvels of milinery, for New York ladies never miss an opportunity of exhibiting their dresses, as they out not to do, and the gentlemen exhibit their gallantry and gloves, and so the Receptions come to an end. And very delightful they are, as we said in the beginning. Some of the artists’s rooms last evening were lighted up and formed the most agreeable lounging places. There in Suydam’s room, for example, besides his own pretty coast scenes, might be seen one of the finest cabinet paintings of the modern French School, a charming little picture by Edouard Frere n, in Gignoux large room might be seen a superb picture of “Niagara Falls by Moonlight” which that accomplished artist has just finished for Mr. Belmont. Niagara has lately been done, artistically speaking, almost to death ; but this grand picture of Gignoux’s throws a new interest over the scene. The artist has invested in the subject, grand as it is, with a new grandeur by his treatment of it. Those who have not seen the great cataract b moonlight, have yet to see it under the most favorable aspects. Mr. Gignoux has most happily chosen, not only the best points of view, but the best time for his purpose. The spot selected, Goat Island, looking over the Horse-shoe, affords the best single e view of the Falls that can be obtained, as the full-orbed moon is sinking over the distant forests on the Canada shore, throwing a flood of silver light over the rushing waters. The scene is full of a solemn grandeur, which the artist has most happily preserved. The Reception was as pleasant an occasion as could be conceived of, but those who wish to see the pictures and sculptures of the Studio artists will go quietly by daylight. “

1864 brought John Ferguson Weir. It was at The Tenth Street Studio Building that he painted his first major work, An Artist’s Studio. (WikimediaCommons)

In 1872, Winslow Homer painted Snap The Whip, and the picture was exhibited in his residence at the Tenth Street Studio Building in 1873. (MetMuseum)

Landscapes eventually fell out of fashion but in 1878, William Merrit Chase took over the central gallery and he brought with him not only a museum’s-worth of exotic wares, but a reviving breath into the lungs of The Studio. Historians often cite his passage from the studio as a signifier of it’s decline, but I have chosen to interpret the period right before as the Golden Age of Tenth Street. Pictured below is W.M. Chase himself in his studio. Notice the light from the glass ceiling bathing the space and his copy of the famous Frans Hals painting over his head. (Wikimedia Commons)

The following photographs of Chase’s studio both document the space he worked in and paint a non-human portrait of the artist himself. William Merritt Chase decorated his space to inspire him and for that reason, his studio in Tenth-Street became a work of art all on its own. It is important to remember that The Tenth Street Studios were not so because they were affordable, but rather they provided the perfect setting for already established, successful, painters, who could afford the relatively high rents. Chase took over the entire central gallery, leaving him plenty of room to display his souvenirs and oddities he collected from all over the world.

W.M. [William Merritt] Chase's studio, West 10th St. N.Y., ca. 1880 / George Collins Cox, photographer. Miscellaneous photographs collection, . Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Based on the number of pictures Chase made of his studio, we can easily see how much he enjoyed this space.

(William Merritt Chase, Studio Interior, 1882. Source)

(William Merritt Chase, A Corner of My Studio, 1895. Source.)

10th Street Studio Building

51 West Tenth Street: The Incubator of American Art

Jacob Riis describes the dwellings of mid to late nineteenth century New York City as being “dirty, dank, windowless, hovels” in How The Other Half Lives: Studies Amongst the Tenements of New York. It was in these spare rooms, unused attic spaces, and extra commercial areas like basements, where artists rented spaces to work in. A savvy businessman named James Boorman Johnston identified a market deficit - adequate studio spaces In 1857, Johnston built The Tenth Street Studio Building. The 51 West Tenth Street was host to historic exhibitions like Frederich Edwin Church’s 1959 Heart of the Andes and society affairs in William Merritt Chase’s extravagantly- decorated studio. Using primary sources, this paper was first conceived in the form of a blog post ( http://newyorkcityvintage.com/post/140584473451/tenth-street-studio- building )for seamless presentation of text and images. The purpose of this research is to create a singular set of comprehensive metadata so that the story of The Tenth Street Studio Building is free and accessible to all people with an internet connection. Using sources from the public domain such as newspaper archives, letters, directories, and images from open-source collections of art and archival institutions, 51 West 10th Street : Incubator of American Art will attempt to revive the experience of one of the most important addresses in art of all time from its birth in 1857 to its death by destruction in 1955.

BIRTH OF THE BUILDING

In the nineteenth century, The United States was still a relatively infantile country and its art was considered accordingly unremarkable. Respectable collectors in America preferred European paintings. In fact, the first American would not be accepted into the

Paris Salon until 1878, a year that was widely considered “disappointing”. (1) Congruous with the despicable attitude that was generally held about American art, most people would have considered James Boorman Johnston’s 1857 investment rather risky or even “experimental” (2). Johnston hired Richard Morris Hunt to design the first-ever artist’s studio building. The Beaux-Arts graduate designed a the building around a European-style “courtyard” that took the form of a glass-ceilinged central communal gallery. Three surrounding floors housed twenty-three studios in varying sizes. Hunt used large windows to provide the sunlight New York artists desperately needed. The building’s facade was done totally in red brick. The walls, moldings, and other accoutrements were all done in the same material.

The first tenants moved in before construction was complete. Rents at 51 West 10th Street were relatively expensive. This was a smart decision on behalf pf Johnston as it attracted only the most successful working artists. By the time construction was complete, the building was filled with artists of all disciplines. Richard Morris Hunt opened his own architecture school and subsequently the first American school of architecture at the Tenth Street Studio building. He was surrounded by painters, sculptors, writers, and philosophers.

51 West 10 Street Earns a Reputation

The Tenth Street Studios were typically open during “acceptable hours” on weekends. In a sort of modified version of a penny museum, visitors would pay to experience art-attractions like seasonal exhibitions, immersive panoramic painting, and sometimes celebrity masterpieces. In 1859 When Frederick Edwin Church exhibited Heart of the Andes for the first time, the Tenth Street Studio building was happily

overwhelmed with visitors. Lines to see the painting reportedly curled around block after block every day it was exhibited. Heart of the Andes generated over $140 each day,

profiting $3000(1-AVERY) by the end of the three-week exhibition at 51 West 10th Street.

However, the success of this exhibition relied on more than just good painting. Even though there are no photographs or drawings depicting this specific exhibition, much was written about it in culture and society columns. According to one writer, the painting sat in a fourteen-foot frame which stood upon the ground to immerse the viewer in the experience and also to keep a constant proper eye-level with the crowd. The walls of the communal gallery were draped in dark fabric to absorb extraneous light from the skylight which was pouring a beam directly onto the painting, seemingly lighting it from within. The painting was covered with a dark velvet curtain that slowly danced open to reveal the glorious scenery. Upon reveal, some people felt overwhelmed by a sense of lightheadedness, vertigo, and overall immersion in the imagery. This was identified at the time as the realization of the sublime. Of course, all this could only be experienced if one was lucky enough to actually see the painting. Even though opera glasses were passed around so viewers could examine every rock, leaf, blossom, and minute scientific detail of the piece, the gallery was described as being so crowded that visitors may need the opera glasses just to see the painting at all. All of this commotion put Church in direct contact with his audience. The communal gallery at the studio temporarily made the traditional gallery/art dealer system obsolete and gave greater business-power to the artists who showed there.

The Tenth Street Studio’s inaugural show was simply the first in a tradition of raucous exhibitions and open studios in the building. Visiting The Tenth Street Studios

was as much an artistic affair as it was a social soectacle. There are numerous newspaper articles from the time period, pouring over the elaborate and vast details of the space. One New York Times article from January 18, 1859 details the experience of one of these affairs. The following text was transcribed from a scan of the article to Rich Text Format and then catalogued to be searchable and accessible by the author of this paper:

“There are few things more delightful, as Mr. Micawber says of a deviled turkey’s leg, than an artist’s reception. It is one of the institutions that have naturally sprung up quite promiscuously and naturally within the past three of four years, and they have been productive of a vast deal of benent both to Society and Art. There are two of these institutions. One is composed of an Association of Fifty Artists who give their reception and exhibit their “works” at the same time in the large room of Dodworth’s Dancing Academy ; the other is more exclusive, and is composed solely of the artists who inhabit the cloisters of the studio in Tenth-Street. The Dodworthians held their first reception for the season a few weeks since and the artists of The Studio held theirs last evening, in the large exhibition-room of the Eccaleobion of the Fine Arts. No pictures or works of art of an kind were admitted, except the productions of the artists of the Studio, and a most brilliant and attractive display they made. The only drawback to the pleasure of the exhibition was the trifling one of not being able to see any of the works exhibited. The great charm, however, of these receptions is not the pictures, nor the sculpture, nor the drawings, but the company. You find yourself, on entering the rooms, if you succeed in entering them, in the midst of a brilliant assemblage of youth, beauty, and fashion; of men worth knowing and women worth seeing ; and being hemmed in on all sides by orbicular spreads of brocade and velvet, you stand still, with your hat above your head, or suffer yourself to be swayed hither and thither by the pressure of the crowd. You catch glimpses of gilt frames in the distance, and now and then you find yourself thrust against a white but unresisting object, which you discover, on turning your head, to be a hideous group of Italian peasants in marble. You know there are charming pictures on the walls, lovely landscapes by Hubbard and Gifford and Quicy Thorndyke and Regis Gignoux, and Suydam and others ; you know there are groups of game by Hays and portraits by Osgood. But what’s the use? You cannot see them. Nobody sees them. But everybody sees everybody and there’s the delight of it. The ladies exhibit their their marvels of milinery, for New York ladies never miss an opportunity of exhibiting their dresses, as they out not to do, and the gentlemen exhibit their gallantry and gloves, and so the Receptions come to an end. And very delightful they are, as we said in the beginning. Some of the artists’s rooms last evening were lighted up and formed the most agreeable lounging places. There in Suydam’s room, for example, besides his own pretty coast scenes, might be seen one of the finest cabinet paintings of the modern French School, a charming little picture by Edouard Frere n, in Gignoux large room might be seen a superb picture of “Niagara Falls by Moonlight” which that accomplished artist has just finished for Mr. Belmont. Niagara has lately been done, artistically speaking, almost to death ; but this grand picture of Gignoux’s throws a new interest over the scene. The artist has invested in the subject, grand as it is, with a new grandeur by his treatment of it. Those who have not seen the great cataract b moonlight, have yet to see it under the most favorable aspects. Mr. Gignoux has most happily chosen, not only the best points of view, but the best time for his purpose. The spot selected, Goat Island, looking over the Horse-shoe, affords the best single e view of the Falls that can be obtained, as the full-orbed moon is sinking over the distant forests on the Canada shore, throwing a flood of silver light over the rushing waters. The

scene is full of a solemn grandeur, which the artist has most happily preserved. The Reception was as pleasant an occasion as could be conceived of, but those who wish to see the pictures and sculptures of the Studio artists will go quietly by daylight.”

It was under these exact exciting circumstances that Emanuel Leutze would have shown Westward The Course of the Empire Takes Its Way in 1860. Leutze’s piece was nearly twice as big as Heart of the Andes, adding competition and in-fighting to the list of benefits of working in The Studio Building.

In 1861, Leutze moved out of the Tenth Street Studio Building and was replaced with Albert Bierstadt. Representing the Hudson River School painters, Bierstadt completed some of his greatest worst at the Tenth Street Studio Building such as Echo Lake, Fraconia Mountains (1862) and The Rocky Mountains, Lander’s Peak (1862). The arrangement of the studio lent itself to the process of the Hudson River School artists. In the summer, they would travel to make studies for paintings, sometimes subletting their studio to other artists. In the Fall, they would return to the Tenth Street Studio Building to dedicate entire winters to articulate the power and divinity of nature. Landscape painting soon fell out of fashion. A change in tastes was marked by new residents of the building like genre painter, Winslow Homer. Homer did a ten year stint in the building, notable for his painting Snap The Whip (1872). The twice-yearly exhibitions would include American greats like William H. Beard and Worthington Whittredge.

Willliam Merrit Chase Returns to America

Over the next decade, the studio building would undergo a tremendous shift. In 1878, William Merrit Chase returned some studying amongst the impressionists in Europe. Chase’s reputation made him privy to the next open studio space and he moved in immediately upon return. Inspired by Europe, Chase envisioned magnificent,

large, paintings (however his painting style was too meticulous to ever complete a large painting). His average-sized studio space on the ground floor of 51 West Tenth Street would not do. The Studio building was experiencing a waning relevancy due to the decline of landscape painting. Seizing the opportunity, William Merritt Chase transformed the central communal gallery into his own personal studio. He buried the space in a “brilliant assemblage”, of exotic wares from his travels around the world. In 1859, James Boorman Johnston offered his brother, who coincidentally was also the Founding President of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, rights to the building. 51 West Tenth Street accepted John Taylor Johnston as its new landlord. William Merritt Chase’s time at The Studio marked a change the way it was run. The Tenth Street Studio building could no longer host public receptions as Chase occupied its gallery. The communal aspect of the building was essentially gone and although Chase’s residency marked a new chapter for 51 West Tenth Street, it also signaled the death of another. Newspapers lamented the loss of the private receptions. Special viewings at The Studio were the only way that friends and families of the artists could see the paintings before they were publicly exhibited.

Chase’s Tenth Street Studio

The Studio itself would become the subject and background of many of William Merritt Chase’s most notable interior scenes. A Corner of My Studio seems to be Chase’s ode to his space. The piece can be viewed as a non-human portrait. The Sun Times describes how Chase’s environment informed his reputation, “William M. Chase, N. A., is pretty widely known, not alone by his own works, which are many and interesting, nor by his pupils only, but as much by reason of his having had for years, in

the old Tenth street studio building, the one conspicuous show studio of the town.” William Merritt Chase is represented through the rich, Victorian decoration. Every inch of every wall and surface is host to a menagerie of foreign fineries. Brilliant light bathes furniture from the glass ceiling above. His style for decorating seemed to inspire the other tenants and by 1887, 51 West Tenth Street became was the most-written about studio in the world, setting a standard for style and eccentricity among the spaces of all subsequent artists. John Taylor Johnston died in 1893 and William Merritt Chase would move back to Europe to teach, leaving his studio and its legacy behind.

Demolition

Chase’s large space was quickly filled by sculptor Stirling Calder. Even though artists would occupy the building for fifty more years, the qualities that fueled the formative years of 51 West Tenth Street were gone. The twentieth century would bring the studio nominal success. It was still occupied by artists but without any special draw, 51 West 10th Street was lost among its backdrop of budding bohemian Greenwich Village. After nearly one hundred years of housing most of America’s greatest and most influential artists, a small notice was given in the New York Times announcing the sale of the property and its planned demolition. Being held together by only residual interest, The Tenth Street Studio Building was unceremoniously razed and replaced with apartments.

Blaugrund, Annette. “The Tenth Street Studio Building: A Roster, 1857-1895”. American Art Journal 14.2 (1982): 64–71. Web.

Disturnell, John. New York As It Was And Is. New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1876. Print.

Gray, Christopher. "Remembering An 1858 Greenwich Village Atelier". New York Times 1997: n. pag. Print.

Hooper, Lucy H.. “The Paris Salon of 1878”. The Art Journal (1875-1887) 4 (1878): 254–255. Web.

Internet Archive". Archive.org. N.p., 2016. Web. 2 May 2016. JSTOR Early Journal Content, “The Crayon,” Volume 5. , January 1898, Web. 2 May 2016. Web.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Happy Birthday, Jayne Mansfield! And New York, get out there today and vote!

Finally found a new Facebook cover photo! - Times Sq Billboard, 60s.

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lower Manhattan from the Top of the Woolworth Building, John Marin, 1922

John Marin was painting during an explosive time in New York. The city was expanding outward and upward at an unprecedented speed. The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

#Painting#1920s#John Marin#Woolworth Bulilding#20s#New York City#Manhattan#Lower Manhattan#Museum of Modern Art#MOMA

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

RIP Phife Dawg. A Tribe Called Quest Downtown in 1989. Photo by Jeanette Beckman.

68 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Edie and Andy at the Factory. Photographed by Susan Wood.

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

1st Avenue & 10th Street Market photographed by Sol Libsohn in New York City 1938.

142 notes

·

View notes

Photo

One of my favorite buildings in New York City.

192 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A reader asked me to try to find some photos of their Dad’s deli at 82-09 Northern Boulevard from around the 40s. Without purchasing the 1939 Tax photo of the specific lot from the Municipal Archives (which might not be helpful anyways since it predates the shop), these are the closest I can come to finding a photo. This will drive me crazy and I’ll probably look for a photo of their Dad’s deli forever.

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jerome Liebling

Lower East Side, New York City, 1947

307 notes

·

View notes