henlo i am a budding hydra, let's talk about our world - aquatic inverts

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Let’s KRILL this love!

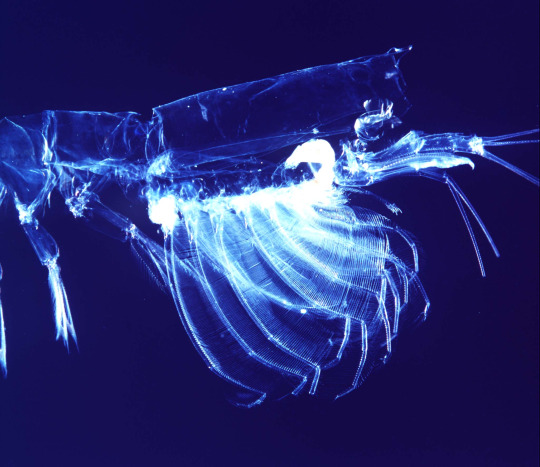

Did you know that Antarctic Krill can glow in the dark (like a lightstick *0*)?

They are bioluminescent! That means krill swarms look like a KPOP ocean!

Classification

Kingdom: Animalia

Subkingdom: Bilateria

Infrakingdom: Protostomia

Superphylum: Ecdysozoa

Phylum: Arthropoda

Class: Malacostraca

Subclass: Eumalacostraca

Order: Euphausiacea

Family: Euphausiidae

Genus: Euphausia

Species: Euphausia superba

(ITIS, n.d.)

Distribution and habitat

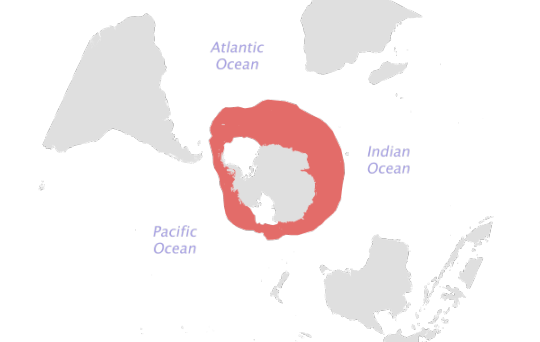

Figure 1. Geographical Distribution of Antarctic krill (fao.org, n,d,)

E. superba inhabits a wide circumpolar belt between the Antarctic Continental Shelf break and the Antarctic Polar Frontal Zone. Antarctic krill live in open marine waters (fao.org, n.d.). The larvae of the krill begin near the seafloor and gradually ascend towards the surface as it develops. Adult krills are found at depths ranging from surface waters to depths of 350 m and have occasionally been found as deep as 600 m. They usually dwell in deeper waters during the winter season (Gierak, n.d.).

Anatomy

Figure 2. External Anatomy of Antarctic Krill

E. superba known as Antarctic krills are shrimp-like in appearance though they can easily be distinguished from shrimp by their visible gills. Just like any other decapods they have exoskeleton which are made of chitin and have three body parts which is the cephalothorax, pleon and the telson. The cephalothorax bears the antennae, compound eye, 6 filter legs which are also called thoracopods and the gills. Krills have compound eyes which aid them in seeing while their antennae serve as another sensory organ as they live in the deep. The thoracopods or the filter legs on the other hand, assists the krill in straining its food from the water. Although the gills, guts and gastric mill are not part of its external anatomy, the three are visible from the outside. The middle part of its body is the pleon where the pleopods and the photophores are located. There are 5 pairs of pleopods or swimming legs that allow them to swim in the water column while the photophores or light organs act as a defense mechanism or a signal for their mates. Lastly, is the telson which is used by decapods as a paddle in caridoid escape reactions through backward propulsion (Grzimek's Student Animal Life Resource, n.d.).

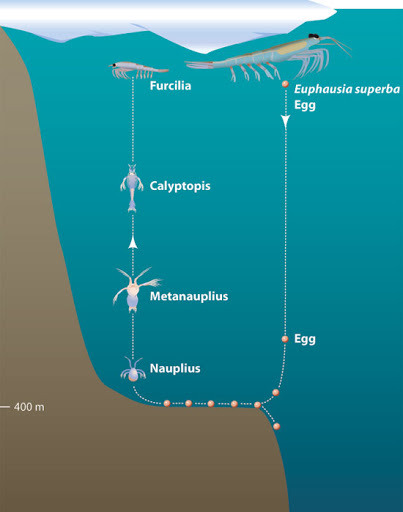

Life Cycle

Figure 3. Life Cycle of an Antarctic Krills Krills reproduce sexually and it usually happens when food is abundant. The male krill produces sperm packets and uses its first pair of pleopods called petasma to transfer the sperm into the thelycum of the female. They store the sperm until they are ready to lay their eggs. These eggs are fertilized once they are released by the female. These eggs settle at the seafloor and gastrulation happens. Eventually, the eggs will hatch and become a nauplius. In this the nauplius has only one eye and is not segmented yet. Then, the nauplius will molt and become a metanauplius wherein limb development begins and it will start to migrate to the surface which is known as developmental ascent. As it molts and grows, it becomes a calyptopis and eventually a furcilia wherein the movable compound eyes start to project at the edge of its carapace. The furcilia develops into a juvenile which can grow from 4 to 10 mm long (Gierak, 2013).

Ecology

Figure 4. Thoracic endopodite of krill (wikipedia.org, n.d.)

Antarctic krill are filter-feeders that feed mainly on phytoplankton. They exhibit diurnal vertical migration, which means that they rise to the surface at night to feed by using their small, hair-like legs specifically thoracic endopodites as a suspension feeding basket. Apart from phytoplankton, they also eat copepods, zooplankton, and other krill or molted exoskeletons. In the winter, they eat algae under the surface of sea ice. They are considered the dominant herbivore of the Southern Ocean. Its biomass in the Antarctic Ocean is estimated to be between 125 mmt and 750 mmt, the largest biomass of any species on earth (Hardy, 2008). Antarctic krill is the keystone species of the entire Antarctic food chain. They provide a vital food source for whales, seals, squids, penguins, fishes, albatrosses, and many other species of birds. To avoid predation, they exhibit schooling behavior or swarming. Moreover, krill may be parasitized by organisms like protozoans, particularly the genus Ephelota. This suctorian ciliates interacting with E. superba cause hydrodynamic drag on krill swimming and make the host more vulnerable to visual predators (Gómez-Gutiérrez & Morales-Ávila, 2016). Other parasitic species include Cephaloidophora pacifica and Apostoma sp.

UNLI-KRILL @ 199!

youtube

Krill’s POV

Relationship with humans

Figure 5. Sports Research’s Antarctic Krill Oil with SUPERBA 2 (ph.iherb.com, n.d.)

Figure 6. Krill/shrimp chili paste and dipping assortments in Thailand (quora.com, 2016)

Although krill is mainly used as aquaculture feed and bait for fishing, it is also processed into a variety of products for human consumption such as paste, frozen tails, sticks, etc. Krill products have been known to pharmaceutical and industrial industries since it is found that the krill's lipid content can be used as a nutritional source of fatty acids that is potential in lowering cholesterol levels. Studies found that the lipids of Antarctic krill are more stable than those of some fishes consumed by humans. Krill digestive proteases can also be injected into humans to reduce pressure on nerve roots between vertebral discs (Gierak, n.d.). Tou et al. describe Antarctic krill as a “rich source of high-quality protein” with low fat and high levels of Omega-3s and antioxidants and the main source of the renowned krill oil.

5 health benefits of Krill oil you shouldn’t miss!

youtube

Little did you know that..

They are age-defying!

*jaw-dropping moment because olay age-defying serum just cant--*

➔ They have the ability to shrink in size when starve to conserve energy during the winter. Thus, scientists can’t tell the age of a krill solely from its size.

Phytoplankton is just a summer fling!

➔ They can survive more than 200 days without food.

Krillions of krills!

➔ Krill swarm together in massive numbers, with as many as 30,000 in one cubic meter of a krill swarm.

A Little Giant!

➔ It’s estimated that the total weight of Antarctic krill is more than the weight of all humans on Earth (Usoceangov, 2015).

Food is life but swimming is lifer!

➔ They are heavier than seawater and must swim constantly to stay afloat.

Climate heroes!

➔ Tarling and Thorpe (2017) have discovered that krill play a crucial role in sequestering carbon.

References:

Clark, D. (2012, September 17). The anatomy of the Arctic krill [Digital image]. Retrieved November 12, 2020, from http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-7NY88MHBVpc/UFfn-sAknuI/AAAAAAAAAW4/nkt1_Ba8G8k/s1600/Antarctic_krill_anatomy.jpg

Euphausia superba. (n.d.). ITIS. Retrieved November 8, 2020, from https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=95514#null

Euphausia superba (Dana, 1852). (n.d.). FAO. Retrieved November 10, 2020, from http://www.fao.org/fishery/species/3393/en

Exuvia of Antarctic krill [Online image]. (2005). English Wikipedia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Exuviakrillkils.jpg

Gierak, R. (2013). Euphausia superba (Antarctic krill). Retrieved November 12, 2020, from https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Euphausia_superba/

Gómez-Gutiérrez, J., & Morales-Ávila, J. R. (2016). Parasites and Diseases. Biology and Ecology of Antarctic Krill, 351–386. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-29279-3_10

Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. (2020). Krill: Euphausiacea. Retrieved November 12, 2020, from https://www.encyclopedia.com/science/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/krill-euphausiacea

Hardy, R. W. (2008). Alternative marine sources of fish feed and farmed fish quality. Improving Farmed Fish Quality and Safety, 328–342. https://doi.org/10.1533/9781845694920.2.328

Naruturd_505. (n.d.). Hoshiumi Korai A Little Giant GIF [Online GIF]. https://tenor.com/view/hoshiumi-korai-alittle-giant-smile-haikyuu-anime-gif-17909731

Oh, yeah- what?! GIF. (2013). Gfycat. https://gfycat.com/detailedfaintalbertosaurus

SuperSmiles17. (2013). Definitely one in a Krillion! [Online GIF]. https://imgur.com/gallery/YtN30/comment/16282449

Tarling, G.A., and Thorpe, S.E. (2017). Oceanic swarms of Antarctic krill perform satiation sinking. Proc. R. Soc. B., 28420172015. http://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2017.2015

The Ozone Hole. (n.d.). [Life Cycle of Antarctic Krill]. Retrieved November 12, 2020, from http://www.theozonehole.org/images/v43n2-wiebe3en_10243.jpg

[Untitled image of a tardigrade]. (2017). BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-40752669

Usoceangov. (2015). Animals of the Ice - Antarctic Krill. Youtube. Retrieved November 10, 2020, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RFqhocQqbgM

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pearly shell from the Ocean-yah!

Can you guess what organism we will talk about just by reading the title?

If not, let’s do the revised version of PPAP song!!!

Classification

Kingdom: Animalia

Subkingdom: Bilateria

Infrakingdom: Protostomia

Superphylum: Lophozoa

Phylum: Mollusca

Class: Bivalvia

Subclass: Pteriomorphia

Order: Pterioida

Family: Pteriidae

Genus: Pinctada

Species: Pinctada maxima

(Gervis and Sims, 1992)

Distribution and habitat

Figure 1. Geographical distribution of Pinctada maxima (red indicates high probability of occurrence; yellow if otherwise) (aquamaps.org, 2019)

Pearl oysters are distributed in Indo-West Pacific: from Nicobar and Andaman Islands to Melanesia; north to Japan and south to Queensland and Western Australia; Borneo and Moluccas (sealifebase.ca, 2020). They are specifically present in 22 countries across Asia and Oceania and a native to five tropical marine ecosystems: the Indian Ocean, Indonesia Sea, Pacific Ocean, West Philippine Sea (South China Sea), and the Sulu-Celebes Sea. They mainly live in clear water under the influence of currents, usually grow in dense colonies and thrive in a variety of habitats, ranging from sand and mud to seagrass beds, deep water reefs, or soft corals, for as long as these are within littoral (close to shore) to a depth of 60 m; and sublittoral (between low tide line and edge of continental shelf) zones at depths of 5 to 30 m (Animalscene.ph, 2018).

Anatomy

Figure 2a-2b. Major external anatomic features; and internal shell surface of a mature P. maxima showing major anatomic and surface features (Humphrey and Norton, 2005)

When the shell is held in the hands, hinge uppermost and horizontal and the byssus is directed away from the observer, the left and the right shell valves of the oyster correspond to the left and right hands of the holder. The hinge corresponds to the dorsal side, the region at the opening of the shell valves is the ventral margin. The byssus marks the anterior region. It is noteworthy that the left shell valve is more convex or arched than the right (Humphrey and Norton, 2005).

The attachment of the adductor muscle is seen as a comma-shaped depression in the centre of the shell. The depressions for the attachment of the retractor muscles of the foot lie immediately anterior-dorsal to the attachment of the adductor muscle. The pallial muscle attachments are seen as irregular linear depressions between the adductor depression and the pallial line. The pallial line is where the pallial muscles attach to the shell valves (Humphrey and Norton, 2005).

Figure 3. The inner surface of two valves of Pinctada maxima from two varieties: gold lip pearl oyster (left) and silver-lip pearl oyster (right); arrows indicate lip colour (Mamangkey, 2009)

Pinctada maxima possesses a pair of valves that are attached with a ligament in the dorsal hinge region and there are no hinge teeth. The right valve is usually flatter than the left. Each valve is composed of three layers: (1) the outer layer is the periostracum or conchiolin layer, which is mainly composed of protein and help reduce biofouling on the outer shell surface; (2) the middle layer is the ostracum or prismatic layer; and (3) the inner layer is the hypostracum or nacre (mother of pearl) layer, which are composed of calcium carbonate (Humphrey and Norton, 2005).

Figure 4. A pair of valves showing shell morphology and orientation: ae (anterior ear); am (adductor muscle scar); bn (byssal notch); li (ligament); ms (pallial muscle scar); nb (nacre border); nl (nacre layer)/ MOP (mother of pearl); pl (prismatic layer); and um (umbo) (Mamangkey, 2009)

Figure 5. Internal anatomy of Pinctada maxima (Mamangkey, 2009)

The mantle covers and protects the internal organs of the shell. It is also responsible for assimilation, respiration, locomotion and reproduction (Simkiss, 1988). The bivalve mantle consists of two lobes of tissue that line the inner surfaces of both shell valves. Each mantle lobe in P. maxima can be divided into three zones: the marginal, pallial and central zones (Dix, 1973; Humphrey & Norton, 2005). Marginal zone splits into three folds: the outer, middle and inner folds. The central zone covers the soft tissue and the pallial zone is composed primarily of muscular threads used in mantle retraction and tissues that are used in the cultured pearl production process (Acosta-Salmón, 2004).

The gill is a crescent-shaped, brown organ that lies between the mantle lobes within the mantle cavity and generally surrounds the outer portion of the adductor muscle (Humphrey and Norton, 2005), and involved with both respiration and ciliary suspension feeding where it filters small particles out of the water which are then transferred to the mouth by a pair of labial palps (Harper, 2005).

Another organ is the adductor muscle that is a large, pale, conspicuous comma-shaped mass that lies generally central to the shell valve, apposing the gills and the mantle and firmly attached to the inner surface of each shell valve. It allows the opening and closing of the valves (Humphrey and Norton, 2005).

Aside from reproduction, the gonad has a great importance in pearl production for it receives the nucleus and nacre-secreting tissue implant required for production (Taylor & Strack, 2008). The ripe gonad of male P. maxima is milky white but it is creamy yellow for females, and when it reaches ripeness, the gonad may occupy one-third of the internal space of the oyster. Full gonads cannot produce pearls because space is needed to house the nucleus and tissue implant. The gonad occupies the posterior region of the visceral mass.

Figure 6. Region of apposition of gill, palps, foot and visceral mass in mature oyster showing major anatomic features (Humphrey and Norton, 2005)

The foot arises as a protrusive, tongue-like organ from the antero-dorsal aspect of the visceral mass, extending towards the byssal notch for burrow and movement. The palps are utilized in feeding and sensory functions. It extends from the proximal termination of the gills to the mouth as four flattened brownish sheets of tissue, arising lateral to the byssal threads and foot. Laterally, the palps merge with the anterior-dorsal mantle. located deep in the terminal closure of the palps and mantle in the anterior-dorsal aspect of the visceral mass is the mouth. The heart is seen as a dark mass within the fine, membranous pericardial cavity, adjacent to the visceral mass on the postero-dorsal aspect of the visceral mass, between the adductor muscle and the visceral mass; subdivided into two portions: the ventricle and the auricles (Humphrey and Norton, 2005).

Life cycle

(Southgate, 2008)

Pearl oysters are protandrous hermaphrodites, which means it begins its life as a male and later changes into a female. P. maxima reach sexual maturity at around 1 year old and 110-135 mm in length. They reproduce by spawning, releasing egg or sperm into the water where fertilization occurs randomly. Temperature is one of the factors that stimulate spawning. Since they are broadcast spawners, there is no parental investment involved. They develop independently starting from trochophore larvae then turn into veliger larvae. As the larvae approach settlement, the foot develops and they start to crawl to look for an appropriate hard surface, if found, the veliger settles on it and metamorphoses into the juvenile stage known as “spat.” They will then start forming shells and become sedentary bottom-dwellers. P. maxima can live up to 40 years. (Welch & Johnson, 2013; “Pearl oyster”, 2013)

Do u think I’m cute? No? To see is to believe 😉 This hooman documented me.

youtube

Ecology

P. maxima (pearl oyster) just like any other bivalves is a filter feeder. They strain minute food particles suspended in the water through their gills. Their diet includes nanoplankton, bivalve eggs, bivalve larvae and other particulate matter. Despite having hard shells, pearl oysters are not free from predators especially at its early stages. Pelagic fishes such as tuna and mackerel often feed on the planktonic pearl oyster larvae. At its spat stage wherein the larvae attach to the substrate, demersal fishes such as snappers are threats to the spats of pearl oyster. Although you would think it is unlikely for adult pearl oysters to have predators, there are still organisms which prey on them such as turtles and boring worms (Fisheries, 2013).

Relationship with humans

Just like the singer P!nk, I’m pretty famous too!

(The Pearl Source, n.d.)

(Pearls Center, 2017)

P. maxima is not only significant in ecology but is also a commercially important species as it produces valuable pearls. These pearls from P. maxima are used as jewelleries, fine quality button and inlay. Since it is difficult to cultivate due to its sensitivity to environmental changes, pearls from the pearl oyster are highly valued.

Did you know?

If you’ve got it, flaunt it!

➔ P. maxima are the largest among other pearl oysters and have the thickest nacre layers, averaging between 2.0-4.0 mm thick or more.

Yes sir, I’m ONE-OF-A-KIND!

➔ They are the rarest of all pearl oysters and produce the most beautiful pearl nacre of any mollusk.

⚠️FRAGILE!

➔ They are extremely sensitive to changes in environmental conditions and must be handled with care in culturing.

✕✕✕✕✕✕✕✕✕ COMMERCIAL BREAK JK ✕✕✕✕✕✕✕✕✕✕✕

A NATIONAL GEM

➔ P. maxima can be found in the 1000 Philippine peso bill.

A BIG FISH

➔ A perfect strand of deep golden South Sea pearls in large sizes can sell for more than $100,000 or over 4 million in Philippine peso (“Golden South Sea Information”, n.d.).

THE PEARL OYSTER:

HUMANS:

References:

Animalscene.ph. (2018). The Pinctada maxima: Producer of the World’s Loveliest Pearls. Retrieved October 15, 2020, from https://animalscene.ph/2018/03/11/the-pinctada-maxima-producer-of-the-worlds-loveliest-pearls/

Aquamaps.org. (2019). Computer generated distribution maps for Pinctada maxima (silverlip pearl oyster), with modelled year 2050 native range map based on IPCC RCP8.5 emissions scenario [Digital Image]. Retrieved October 15, 2020, from https://www.sealifebase.ca/images/aquamaps/native/pic_W-Msc-464492.jpg

Bagapuro, L. (n.d.). Philippine Peso [Online image]. Pinterest. https://www.pinterest.ph/pin/116108496627088701/

Ezell, A. (n.d.). Tv Quotes [Online image]. Pinterest. https://i.pinimg.com/originals/bd/e8/31/bde83115cac997439b66ebf153c7d25e.jpg

Features - Australian South Sea Pearls. (2017). Retrieved October 17, 2020, from http://www.australiansouthseapearls.com/the-world-s-finest-pearls

Fisheries. (2013, April 24). Pearl Oyster. Retrieved October 17, 2020, from http://www.fish.wa.gov.au/species/pearl-oyster/Pages/default.aspx

Gervis, M.H. & Sims, N.A. (1992). The Biology and Culture of Pearl Oysters (Bivalvia: Pteriidae). Retrieved October 12, 2020, from https://www.worldfishcenter.org/libinfo/Pdf/Pub%20SR76%2021.pdf

Golden South Sea Information. (n.d.). Pearlparadise. Retrieved October 12, 2020, from https://www.pearlparadise.com/pages/golden-south-sea-information

Harper, E.M. (2005). Fossil Invertebrates: Bivalves: Soft Part Anatomy. Retrieved October 15, 2020, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/earth-and-planetary-sciences/bivalve#:~:text=In%20most%20bivalves%2C%20the%20gills,on%20the%20feeding%20process%20employed.

Humphrey, J.D. and Norton, J.H. (2005). The Pearl Oyster Pinctada maxima (Jameson, 1901). An Atlas of Functional Anatomy, Pathology and Histopathology. Retrieved October 15, 2020, from http://www.frdc.com.au/Archived-Reports/FRDC%20Projects/1997-333-DLD.PDF

Mamangkey, N. (2009). Improving the quality of pearls from Pinctada maxima. PhD thesis, James Cook University. Retrieved October 15, 2020, from http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/11722

Palomares, M.L.D. and D. Pauly. (2020). Pinctada maxima (Jameson, 1901) silverlip pearl oyster, data taken from SeaLifeBase by SAUP Database. 2006. Retrieved October 15, 2020, from https://www.sealifebase.ca/summary/Pinctada-maxima.html#

Pearl oyster. (2013). Government of Western Australia. Retrieved October 12, 2020, from http://www.fish.wa.gov.au/species/pearl-oyster/Pages/default.aspx

Pearls Center. (2017). [Diving for pearl oysters]. Retrieved October 17, 2020, from http://www.pearlscenter.com/australian-pearl-oyster/

Southgate, P. (2008). Generalized development scheme for pearl oysters from fertilized egg through larval development to adult [Online Image]. Sciendirect. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780444529763000073

The Pearl Source Blog. (n.d.). [Pearl jewelries]. Retrieved October 17, 2020, from https://www.thepearlsource.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Valuable-Pearls-700x480.jpg

[Untitled illustration of spider man]. (n.d.). Makeameme.org. https://makeameme.org/meme/when-she-thicc-c87c59

[Untitled GIF]. (2019). Kpopsicle. https://kpopsicle.co/g-dragon-one-of-a-kind/

Welch, D.J. & Johnson, J.E. (2013). Assessing the vulnerability of Torres Strait fisheries and supporting habitats to climate change. Report to the Australian Fisheries Management Authority. C2O Fisheries. Researchgate. Retrieved October 12, 2020, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309043114_Assessing_the_vulnerability_of_Torres_Strait_fisheries_and_supporting_habitats_to_climate_change_Report_to_the_Australian_Fisheries_Management_Authority_C2O_Fisheries

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE "NOT-S0″ NAUGHTY LUZ

Classification

Kingdom: Animalia Subkingdom: Bilateria Infrakingdom: Protostomia Superphylum: Lophozoa Phylum: Mollusca Class: Cephalopoda Subclass: Nautiloidea Order: Nautilida Family: Nautilidae Genus: Nautilus Species: Nautilus pompilius

Distribution and habitat

Fig. 1 Chambered nautilus (Kalpana, 2018)

Nautilus pompilius, also known as the chambered nautilus, lives in the deep warm waters of the Western Pacific Ocean and Indian Ocean wherein there is little light. Most nautilus species spend most of the day in the deep and only swim upwards to the coral reef slopes at night to search for food. Among them, Nautilus pompilius is the most widespread species (Kennedy, 2019).

Anatomy

Fig. 2 External Anatomy of Nautilus pompilius Top: (Barord, 2015), Bottom: (Basil, 2008)

The chambered nautilus is the only cephalopod with an outer shell. This shell, which protects it, has chambers which have separation. This helps the nautilus to be more buoyant and even control its vertical movement by manipulating the fluid inside these chambers. Aside from this, it also has a hyponome or siphon which helps it move through jet propulsion. Like other cephalopods, nautilus has tentacles but it is not just ten or eight but it may have up to 90 tentacles. Its tentacles do not have suckers, which most cephalopods do, but are lined with sticky grooves that aids it in catching its prey. The digital tentacles are not just for grasping but also have sensory functions. Then, it also has buccal tentacles which surround the buccal area. Aside from these, it also has pre-ocular and post-ocular tentacles, which have sensory functions, located behind and in front of the eye. Another interesting thing about nautilus is their eyes. Although large, their eyes lack lenses but have pin holes which allow light to enter. All these tentacles are accommodated in sheaths except the buccal tentacles. Below the eye sac, are two other organs: rhinophore which is another sensory organ and a pair of statocyst which is a balance sensory receptor (Barber, 2010).

Life cycle

Mini nautilus shellebrating its hatchday

youtube

Chambered nautiluses reproduce through internal fertilization. Males transfer sperm into the females’ mantle cavity using his spadix, a composite erectile organ made up of four modified tentacles. Mating process can last up to 24 hours. The females then lay fertilized eggs to a hard surface such as rocks, each egg is around 3.8 cm in length. The gestation period takes about 9-12 months before emerging as a hatchling. The shells of newly hatched chambered nautiluses are about 2.5 cm in diameter (“Chambered Nautiluses”, n.d.) and the largest of all cephalopods. It takes 15-20 years of age for nautiluses to reach sexual maturity.

Ecology

youtube

Since chambered nautiluses possess a pinhole eye, which does not have a lens, they rely heavily on their sense of smell to detect food. They are nocturnal opportunistic feeders that feed mainly on small fishes, crabs, and carrion (Attenborough 1979, Morton 1979). Their tentacles do not sting their prey, but stick to it. Some of the natural predators of nautilus are octopuses, sharks, triggerfish, groupers, and snappers (“Chambered Nautilus”, 2017). Large predators are able to penetrate the nautilus shell.

Relationship with humans

Fig. 3 Top: Nautilus in the Great Barrier Reef (Fleetham, n.d.), Bottom: Nacre (Lenzi, 2016)

Nautilus pompilius have economic importance where it supports a substantial shell trade especially from beach drift specimens and artisanal fisheries. Researchers have come upon a process called biominetrics, where the outer layers of the shell reveal a silvery mother-of-pearl that lines the inside of N. pompilius' shell. This material is synthesized to produce an organic material such as nacre and it can be of great use in small machines. In the Philippines, the meat is sometimes consumed by the locals. In addition, researchers are fond of using the species as a research subject because of their unique uncommon eye type (Clery 1992 and Nilsson 1989).

Did you know?

Nautiluses have existed before any other organisms, even dinosaurs. They are a deep-branching lineage within the cephalopod phylogeny and split-off early on from other lineages, causing its shell as a mark of this ancient evolutionary divergence.

Out of the 10,000 nautilus species that once existed, only six are still around – including the Chambered Nautilus.

They have highly developed sense of smell with the chemoreceptors in the pore under their eyes or also known as “pinhole eyes”.

^^THE THING U CAN’T UNSEE BUT FOCUS ON MY EYES NOT THE FACE PLEASE!!!

Nautiluses have about 90 suckers and none of them are equipped with suckers, instead rely on sticky ridges and grooves for grasping.

They have efficient metabolism and spend minimal energy for locomotion [hence, not-so-naughty luz] and can go on a month without eating.

References

Attenborough, D. (1979). Life on Earth. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

Barber, V.C. (2010) The Sense Organs of Nautilus. In: Saunders W.B., Landman N.H. (eds) Nautilus. Topics in Geobiology, vol 6. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-3299-7_14

Barord, G. (2015, October). Photograph of Nautilus pompilius caught in the Philippines with general anatomical features labeled [Digital image]. Retrieved October 08, 2020, from https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Photograph-of-Nautilus-pompilius-caught-in-the-Philippines-with-general-anatomical_fig1_286937206

Basil, J. (2008, March). Lateral view of Nautilus pompilius pompilius [Digital image]. Retrieved October 08, 2020, from https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Lateral-view-of-Nautilus-pompilius-pompilius-depicting-various-external-components-with_fig2_228617630

Chambered Nautilus. (2017). Fws.gov. Retrieved October 09, 2020, from https://www.fws.gov/International/animals/nautilus.html#:~:text=Natural%20predators%20of%20nautilus%20include,may%20also%20prey%20on%20nautilus

Chambered Nautiluses. (n.d.). Marinebio. Retrieved October 09, 2020, from https://marinebio.org/species/chambered-nautiluses/nautilus-pompilius/

Fleetham, D. (n.d.). Nautilus in the Great Barrier Reef [Digital image]. Retrieved October 09, 2020, from https://www.agefotostock.com/age/en/Stock-Images/Rights-Managed/PAC-1982381

Goetz, B. (2000). "Nautilus pompilius" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved October 09, 2020, from https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Nautilus_pompilius/

Headfoot. (2016). Nautilus Rage Face: A New Template. IMGFLIP. https://imgflip.com/i/1b5kvk

Kalpana, K. (2018, June 20). [Chambered Nautilus]. Retrieved October 08, 2020, from https://alchetron.com/Nautilus

Kennedy, J. (2019, December 13). Fascinating Nautilus Facts. Retrieved October 08, 2020, from https://www.thoughtco.com/fascinating-facts-about-the-nautilus-2291853

Lenzi, P. (2016). Nacre, Poesy Plus Polemics. Retrieved October 09, 2020, from https://poesypluspolemics.com/2016/04/29/nacre/

Morton. (1979). Molluscs. London: Hutchinson & Co.

Nautilus pompilius. (2013). Retrieved October 09, 2020, from http://cr2chicago.weebly.com/with-every-drop/cephalopod-of-the-week-4-chambered-nautilus

Runck, A. (2018). Nautilus pompilius. Retrieved October 09, 2020, from https://australian.museum/learn/animals/molluscs/nautilus-pompilius/

That’s Shocking [Online GIF]. (n.d.). GIPHY. https://giphy.com/gifs/mrw-elf-imdb-Qphre1I5uUdZ6

The Coral Reef Generation Project. (2013, February). Cephalopod of the Week: Nautilus pompilius. Retrieved October 09, 2020, from http://cr2chicago.weebly.com/with-every-drop/cephalopod-of-the-week-4-chambered-nautilus

[Untitled GIF of a Nautilus]. (2020). GIPHY. https://giphy.com/gifs/OeRWVxiBVedDeIvqvf

[Untitled GIF of a Nautilus]. (2020). GIPHY. https://media2.giphy.com/media/mBvwjrojZiPX4spz1u/200w.webp

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Nude Dancer

Welcome to the nudist show...

but first let’s get to know to know the different sea slugs.

Presenting: The Nude Dancer

Classification

Kingdom: Animalia

Subkingdom: Bilateria

Infrakingdom: Protostomia

Superphylum: Lophozoa

Phylum: Mollusca

Class: Gastropoda

Subclass: Opisthobranchia

Order: Nudibranchia

Suborder: Doridina

Family: Hexabranchidae

Genus: Hexabranchus

Species: H. sanguineus

Did you know that...

The scientific name of H. sanguineus describes its appearance? Hexabranchus means “six gills” while sanguineus means “blood-colored” (”The Enchanting Dance of the Hexabranchus Sanguineus”, 2015) .

Out of 3,000 nudibranch species, the Spanish dancer is the only nudibranch that can swim.

It is the largest nudibranch and measures around 40 cm in length.

It violently flaps its gills and displays its bright colors when threatened which resembles a flamenco dancer, giving it its name the Spanish Dancer (Oceana, n.d.).

Where does this nudist thrive?

This nudibranch occurs in coral and rocky reefs. Regions where this slug is found include the Tropical Western Pacific and Indian Oceans.

A dancer’s body

Anatomy of a dorid nudibranch (Pictton, 1994)

Anatomy of an aeolid nudibranch (Pictton, 1994)

The Spanish Dancer Sea Slug is a dorid nudibranch. Dorid nudibranchs breathe through gills that are located at their back. The other suborder, which are the aeolid nudibranchs on the other hand, have cerata or finger-like projections extending from their mantle which are used not only for respiration but also for digestion and defense. Aside from the gills that distinguish dorid nudibranchs from aeolid ones, dorid nudibranchs also have mantles which extend over the foot. Tubercles may be found in the mantle which is a key characteristic in identifying nudibranchs. The mantle may also have acid glands and spicules in it which are used for defense. Nudibranchs also have rhinophores for chemosensory functions and a foot for locomotion. While Spanish Dancer may not have it, many nudibranchs may also possess oral tentacles which aid them in identifying their food aside from their rhinophores (The Invertebrates Collection, 2018).

A Dancer’s Life

Nudibranchs are simultaneous hermaphrodites which means they possess both male and female reproductive organs. In copulation, both individuals are donating and storing sperm. They lay eggs close to a food source to ensure that the larvae will be able to feed when they come out. The eggs also contain chemical toxins to ward off any predators. Once the eggs are hatched, the larvae move into deeper water where they develop into the adult form (“Diving with Nudibranchs”, n.d.). During the juvenile stage, they drop their shells that they have developed in the larval stage.

How it dances with the others...

The Spanish Dancer is a carnivorous animal. It feeds on at least 11 genera of sponges from 5 orders and 2 classes, even the toxic ones from the Halichondra family. It uses radula which contains macrolides. The macrolides and the Spanish dancer partake in a parasitic relationship, wherein the macrolides allow the nudibranch to produce a toxic chemical for protecting its eggs from predators. These toxins allow the nudibranchs to survive from predation (Pawlik et al., 1988). The Spanish dancer also shares a mutualistic relationship with the Periclimenes imperator, a species of shrimp. It lives inside the gills of the nudibranch to protect themselves from predators and keeps the gills clean in exchange for a small amount of food supply (Maui Ocean Center, 2013).

Man and the Nudist

H. sanguines have little to no significance to humans since they are poisonous. However, its beauty and captivating dance attract hobbyists, divers, and snorkelers. Nudibranchs also attract the attention of natural product researchers due to the potential for discovery of bioactive metabolites, in conjunction with the interesting predator-prey chemical ecological interactions that are present (Dean and Prinsep, 2017).

References:

Dean, L.J. & Prinsep, M.R. (2017). The chemistry and chemical ecology of nudibranchs. Natural Product Reports 34(12): 1359-1390. https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2017/np/c7np00041c#!divAbstract

Diving with Nudibranchs. (n.d.). Dive the world. Retrieved 3 October 2020, from https://www.dive-the-world.com/creatures-nudibranchs.php#:~:text=Life%20Cycle&text=Once%20hatched%2C%20the%20growing%20larva,for%20a%20few%20of%20weeks

Jewell, G. (n.d.). Spanish Dancer [Online image]. Pinterest. https://www.pinterest.ph/pin/373658100327553717/

Jones, A. (2016). Meet the nudibranch: Seven reasons these 'naked' gastropods are more than pretty faces. Retrieved 4 October 2020, from https://amp.abc.net.au/article/7658610

Moenning, A. (n.d.). Hexabranchus Sanguineus: The Real Spanish Dancer. Retrieved 4 October 2020, from http://bioweb.uwlax.edu/bio203/f2013/yurk_devi/index.htm

Oceana.org. (n.d.). Cephalopods, Crustaceans, & other Shellfish: Spanish Dancer. Retrieved 4 October 2020, from https://oceana.org/marine-life/cephalopods-crustaceans-other-shellfish/spanish-dancer

[Online image]. (2019). Twitter. https://twitter.com/eveninghawk/status/1138474776299757569/photo/1

Picton, B. (1994). Anatomy of an aeolid nudibranch [Online image]. Retrieved October 04, 2020, from http://www.seaslug.org.uk

Picton, B. (1994). Anatomy of a dorid nudibranch [Online image]. Retrieved October 04, 2020, from http://www.seaslug.org.uk

Picton, B. E. & Morrow, C. C. (1994). A Field Guide to the Nudibranchs of the British Isles. Retrieved October 04, 2020, from http://www.seaslug.org.uk/nudibranchs/

Spanish dancer nudibranch. (n.d.). 123rf. https://www.123rf.com/photo_70265164_spanish-dancer-nudibranch.html

Spanish Dancer Sea Slug (Great Barrier Reef). (2018). Reddit. Retrieved from https://gfycat.com/enviousadmirablebeauceron

The Enchanting Dance of the Hexabranchus Sanguineus. (2015). Leisurepro. Retrieved 3 October 2020, https://www.leisurepro.com/blog/explore-the-blue/enchanting-dance-hexabranchus-sanguineus/

[Untitled gif of Spanish Dancer]. (n.d.). Gifer. https://gifer.com/en/AHs6

[Untitled illustration of Spanish dancer]. (2015). Pink tank scuba. https://pinktankscuba.com/2015/09/21/spanish-dancers-the-biggest-nudibranchs-in-the-world/

Whyte, R. (2016). The Spanish Dancer nudibranch, and its eponym [Online image]. Flickr. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-07-29/spanish-dancer-nudibranch-and-model.jpg/7669392?nw=0

#gastropod seaslug nudibranchs#hexabranchus#mollusks#seaslugs#nudibranchs#opisthobranchia#spanish dancer#gastropods#aquatic invertebrates#invertebrates#mollusc#sea#slugs#butterflies of the sea#science#biology#ecology#discovery#nude#poisonous#naked gills#fish#anatomy#lifecyleofseaslugs#lifecycle#reproduction#hermpaphrodites#interesting facts#taxonomy#taxonomic classification

4 notes

·

View notes