epifight

933 posts

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

Moldy Fruit Sculptures Formed From Precious Gemstones Challenge Perceptions of Decoration and Decay

40K notes

·

View notes

Photo

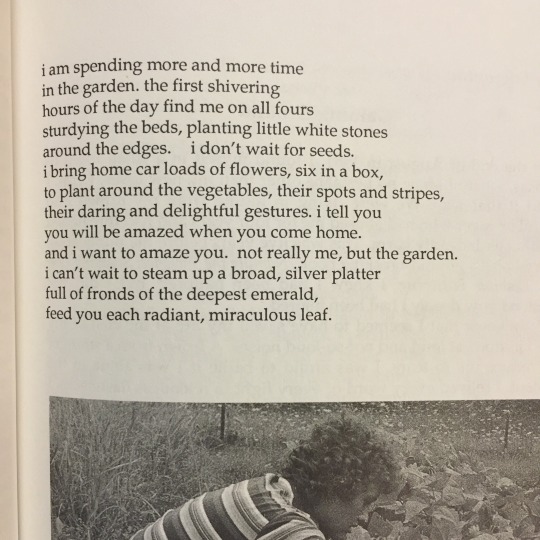

CV Dazzle is a response. It is a form of expressive interference that combines highly stylized makeup and hair styling with face-detection thwarting designs. CV, or computer vision, Dazzle is an updated version of the original dazzle camouflage from WWI, which was used to protect warships from submarine attacks. Like the original dazzle war paint, CV Dazzle is an unobvious style of camouflage because its eye-catching patterns and colors draw attention instead of hiding from it. As decoration, CV Dazzle can be boldly applied as hair styling or makeup, or together in combination with accessories. As camouflage, this facial markup works to protect against automated face detection and recognition systems by altering the contrast and spatial relationship of key facial features. The variations are limitless.

Camouflage from face detection. CV Dazzle.

5 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Korean Street Food | Ggultarae (Dragon's Beard Candy), in Insa-Dong, Seoul Korea

1 note

·

View note

Text

From Rape culture: would prison abolition help women?

But showing that prisons are sites of systemic sexual violence does not establish that immediate abolition would lead to quantitatively fewer rapes. The question is then if these carceral functions cannot provide the framework for eliminating rape and assault, what alternative structures can be established?

One option is ‘restorative justice’, involving facilitated meetings between the perpetrator and victim - to enable answers for any questions the victim has of the perpetrator, or acknowledgement of the harm caused. The New Zealand-based Project Restore is prominent in advocating this approach, which stems out of Maori accountability practices. In theory, this might provide some conciliation - equilibrium can be restored to the disrupted families, communities, and networks, if only by having the perpetrator acknowledge fault.

However, even Project Restore concedes the limits of such an approach. It does not, by itself, create conditions that enable safety and resistance to violence and oppression - or provide reparations to victims. Indeed, these projects gained traction within neoliberal approaches seeking cheaper alternatives to incarceration. Even the name, ‘restorative’ justice, reveals the limits of its intended effect. Rather than accountability for the victim and recognition of their needs, the peace of communities and families that failed to protect the victim from violence is intended – to restore things as they were.

Another alternative is ‘transformative justice’, which focuses on developing ‘community accountability’ structures to disrupt cycles of abuse and assault. This framework has been developed by women of colour-led US groups like INCITE!, Sista II Sista, and Communities Against Rape and Abuse (CARA), who organise against interpersonal and state violence. The idea is that support groups from the community facilitate a process between the victim and the perpetrator, and a process of dialogue and admission of responsibility by the perpetrator then approximates the necessary steps to repair harm. The support groups then monitor whether these steps are maintained.

'Transformative justice’ is centred in developing the community’s autonomy in order to prevent violence. It sees retribution as reactive, and incarceration as unable and incapable of unpacking more difficult questions about state violence, or the complicity of communal networks that feel obligated to intervene to stop drink driving, for example, but not child abuse.

But a 'transformative’ solution cannot simply involve a sentimentalised restorative justice system with a neoliberal renovation i.e. one that prioritises restoring unequal power relations for the sake of 'peace’ or expense, or transferring arbitrary judicial functions to communities, assuming this accounts for all of the survivor’s needs.

Generation Five, an organisation focusing on transformative justice in cases of child abuse, importantly state: “Without a just world, people cannot find healing and safety.” The primary task in communities and organisations attempting to articulate a response to violence is providing care and support to survivors, including being led by survivors’ needs and desires regarding their abusers.

But this has to be integrated with attempts to eradicate the inequities that allow patriarchal violence to occur.

'Transformative justice’ is contingent on broader social and personal transformation. Just as prison abolition is only conceivable by shifting resources to healthcare and education systems and removing the violence of poverty, 'transformative justice’ cannot simply depend on the community being inherently more accountable than the courts: it also has to identify the absence of reparations and accountability for the victims - and redistribute power to them.

While consent-based sex education is entrenched in discourse about how to tackle rape culture, and an important first step in beginning a shift towards transformative justice, there must also be a broader realisation of reproductive autonomy to redistribute power - for example abortion on demand, and trans-appropriate healthcare.

A transformative discourse about tackling rape culture would also consider the institutionalised violence of local authority care homes - which feed women and children into the violence of homelessness, addiction, and prisons.

Children’s rights are also vital to conceiving social and personal transformation as a means of dismantling rape culture. Children need more than comprehensive sex and relationship education: they also need greater democratic power in schools, and in their lives.

Without the broader empowerment of those vulnerable to patriarchal and sexual violence, transformative justice mechanisms no more provide accountability and reparations for rape survivors than our current carceral apparatus. And community accountability is anemic without addressing the ways in which women, particularly women of colour, women with disabilities and trans women, are trapped by the violence of poverty, or state violence.

In moving beyond a model of incarceration that exacerbates rape culture, transformative justice has to take account of survivors’ complex needs. It must ensure community accountability does not simply whitewash the systems that enable patriarchal violence.

683 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hyperrealist colored pencil drawings of giant dabs of thick oil paint created by Cj Hendry

58K notes

·

View notes

Quote

The 'abject' aspect of hatred of certain objects and others which results in various efforts at demarcation lies, then, in its necessary subjective failure. Furious efforts to separate from those who we have learnt within a particular society to designate as dangerous or fearful by means of historically specific social and spatial strategies (and spatial separation is only one possible strategy here) signal their inevitable failure in their very fury. The danger, the fear, is within; and the emotional energy, if it is indeed a product of abjection, signals the perpetrators' knowledge that the threat will persist, both subjectively and quite possibly socially, despite their best demarcating efforts. The spatiality of abjection and of the semiotic, then, is precisely about the persistent failure of borders, distinctions and separations.’ (Robinson, 2000: 296).

Robinson, J. (2000). ‘Feminism and the Spaces of Transformation’, p. 296.

5 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Mixing Face Powder (1958), British Pathé

0 notes

Quote

You know, you see how different all these women are who suffer violence. This was a very important step in this discussion of domestic violence – to accept that most women who suffer violence are not equal, and that they do not like each other. It is not easy to live together in a shelter – and being so different. The only thing connecting the women is that they have suffered violence and they need a safe place. And this is a very poor, very small thing to keep them together in shelter life. So it is very important to recognize these differences.

Barbara Kaveman, interviewed in Janice Haaken’s Hard Knocks: Domestic Violence and the Psychology of Storytelling (2010).

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

The following essays were written one each month for about two years [...] on topics suggested by current events. I was at the time trying to reflect regularly on some myths of French daily life. The media which prompted these reflections may well appear heterogeneous (a newspaper article, a photograph in a weekly, a film, a show, an exhibition), and their subject matter very arbitrary: I was of course guided by my own current interests. [...] Having been written month by month, these essays do not pretend to show any organic development: the link between them is one of insistence and repetition. For while I don’t know whether, as the saying goes, “things which are repeated are pleasing”, my belief is that they are significant. And what I sought throughout this book were significant features. Is this a significance which I read into them? […] is there a mythology of the mythologist? No doubt, and the reader will easily see where I stand.

Preface (1957) to Roland Barthes’ Mythologies. Translated from the French by Annette Lavers.

0 notes

Quote

We are volcanoes. When we women offer our experience as our truth, as human truth, all the maps change. There are new mountains.

Ursula K. Le Guin (1989), Dancing at the edge of the world, p. 160.

6 notes

·

View notes