The forces that drive the universe are not so very different from those that drive humanity. This is an opera blog. Ask me questions!

Last active 4 hours ago

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

bach's concerto for two violins in d minor remains the song of the summer for 295 years in a row

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

i made this for my wikipedia account but you guys would enjoy thsi too

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

in honor of the best Dropout clip of all time

24K notes

·

View notes

Text

Sorry I've been away from Tumblr for so long I've been listening to Schreker orchestral lieder #sigmamindset

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Salome, Elektra, Lulu?

[put the name of an opera in my inbox, and I’ll tell you how I would direct it/what my production concept(s) would be]

THREE FAVORITES HERE WE GO

Salome

So Salome is an interesting opera in that it’s kind of a weird one in Strauss’ output, and I think overall much weirder than people tend to appreciate. Before Salome, he was basically a promising third-tier composer, and after, he became Strauss. When he left Salome behind, he left a lot with it–an obsession biblical source material, 19th-century style exoticism, and a certain style of sensationalist violence that never really comes back again. Later violent scenes from Strauss, at least for me, seem to come with a bleaker weight and knowledge of the consequences of that violence (at least in the musical representation of it). Salome, on the other hand, is basically Quentin Tarantino violence–consequence-free blood splatters that cross into perverse, even erotic territory. That’s what I want out of a Salome. I want the audience to feel like they need a loooong shower before they can go out and face their world again. I want blood splatters on the stage in comical amounts, horror movie sets, and I want people to feel a bit physically ill afterwards, you know? During the final moments of the opera, I want Salome to physically get as close as possible to the audience, really luxuriating in the excess of the whole proceedings. Kids will not be allowed.

Elektra

Elektra is very much a sister piece for Salome, but with almost the opposite affect–at least when it comes to the violence. I would want my Elektra to be a mirror image of my Salome (it would be AMAZING if they could be done as a double feature or on consecutive nights). Elektra, as an opera, is the realization that aesthetic violence has consequences in the way that Salome never does. If Salome is a wild night of hedonistic abandon, Elektra is the hangover. Salome is colorful and exotic, Elektra is gray and tomblike. I would want my Elektra to be an examination of the reckless enjoyment of aesthetic violence that we indulged in for my Elektra, and really confront the horror of what that might actually be like. I think the sets and costumes for Elektra would have a similar aesthetic to my Salome, but more drab, perhaps even clinical. Ghosts of the carnage of Salome (perhaps literally projections of images of that cast, or maybe just metaphorical references if I’m feeling subtle) should float through the background in shadow. Perhaps some double-casting could be accomplished for minor roles that would bring attention to the idea of Salome and Elektra being two sides of the same coin. I do think that the ending of Elektra, however, should transcend this concept somewhat–perhaps daylight and color begin to come into the scene as she begins her dance, growing in intensity until she falls dead, plunging the scene back into gray, cracked darkness.

Lulu

Lulu is a phenomenal opera, but one I don’t feel qualified to direct myself (at least, not fully). I’d more or less like to start from scratch with a cast that would approach the opera more like a devised piece, largely driven by whoever plays Lulu, preferably Barbara Hannigan. I do NOT want a naturalistic take on Lulu, but beyond that, I’m open to what they come up with. Every singer I’ve heard play Lulu, especially Hannigan, has completely understood and invested themselves in the character in a way that has blown my mind every time I hear them speak. This, added to the fact that I am not a woman, drives home the point to me that Lulu needs to be largely driven by the person who plays her, far beyond the performance that happens onstage. She needs to be a large part of the process, helped along by the rest of the ensemble as they create something uniquely theirs and unlike any Lulu that could ever be made by anyone else.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

on neuschwanstein castle (part 1)

This is an essay in two parts.

Neuschwanstein Concept Drawing by the stage designer (!!) Christian Jank (1869).

There exist in architecture clear precedents to the McMansion that have nothing to do with suburban real estate. This is because “McMansionry” (let’s say) has many transferable properties. Among them can be included: 1) a diabolical amount of wealth that must be communicated architecturally in the most frivolous way possible, 2) a penchant for historical LARPing primarily informed by media (e.g. the American “Tuscan kitchen”) and 3) the execution of historical styles using contemporary building materials resulting in an aesthetic affect that can be described as uncanny or cheap-looking. By these metrics, we can absolutely call Neuschwanstein Castle, built by the architect Eduard Riedel for King Ludwig II of Bavaria, a McMansion.

Constructed from 1869 through 1886 – the year of Ludwig’s alleged suicide after having been ousted and declared insane – the castle cost the coffers of the Bavarian state and Ludwig himself no fewer than 6.2 million German gold marks. (That's an estimated 47 million euros today.) The castle's story is rife with well-known scandal. I'm sure any passing Swan Enthusiast is already familiar with Ludwig’s financial capriciousness, his called-off marriage and repressed homosexuality, his parasocial obsession with Richard Wagner, his complete and total inability to run his country, and his alleged "madness," as they used to call it. All of these combine to make Neuschwanstein inescapable from the man who commissioned it -- and the artist who inspired it. Say what you like about Ludwig and his building projects, but he is definitely remembered because of them, which is what most monarchs want. Be careful what you wish for.

Neuschwanstein gatehouse.

How should one describe Neuschwanstein architecturally? You’d need an additional blog. Its interiors alone (the subject of the next essay) range from Neo-Baroque to Neo-Byzantine to Neo-Gothic. There are many terms that can loosely define the palace's overall style: eclecticism, medieval revivalism, historicism, chateauesque, sclerotic monarchycore, etc. However, the the most specific would be what was called "castle Romanticism" (Burgenromantik). The Germans are nothing if not literal. Whatever word you want to use, Neuschwanstein is such a Sistine Chapel of pure sentimentality and sugary kitsch that theme park architecture – most famously, Disney's Cinderella’s castle itself – owes many of its medieval iterations to the palace's towering silhouette.

There is some truth to the term Burgenromantik. Neuschwanstein's exterior is a completely fabricated 19th century storybook fantasy of the Middle Ages whose precedents lie more truthfully in art for the stage. As a castle without fortification and a palace with no space for governance, Neuschwanstein's own program is indecisive about what it should be, which makes it a pretty good reflection of Ludwig II himself. To me, however, it is the last gasp of a monarchy whose power will be totally extinguished by that same industrial modernity responsible for the materials and techniques of Neuschwanstein's own, ironic construction.

In order to understand Neuschwanstein, however, we must go into two subjects that are equally a great time for me: 19th century medievalism - the subject of this essay - and the opera Lohengrin by Richard Wagner, the subject of the next. (1)

Part I: Medievalisms Progressive and Reactionary

The Middle Ages were inescapable in 19th century Europe. Design, music, visual art, theater, literature, and yes, architecture were all besotted with the stuff of knights and castles, old sagas, and courtly literature. From arch-conservative nationalism to pro-labor socialism, medievalism's popularity spanned the entire political spectrum. This is because it owes its existence to a number of developments that affected the whole of society.

In Ludwig’s time, the world was changing in profound, almost inconceivable ways. The first and second industrial revolutions with their socioeconomic upheavals and new technologies of transport, manufacturing, and mass communication, all completely unmade and remade how people lived and worked. This was as true of the average person as it was of the princes and nobles who were beginning to be undermined by something called “the petit bourgeoisie.”

Sustenance farming dwindled and wage labor eclipsed all other forms of working. Millions of people no longer able to make a living on piecemeal and agricultural work flocked to the cities and into the great Molochs of factories, mills, stockyards, and mines. Families and other kinship bonds were eroded or severed by the acceleration of capitalist production, large wars, and new means of transportation, especially the railroad. People became not only alienated from each other and from their labor in the classical Marxist sense but also from the results of that labor, too. No longer were chairs made by craftsmen or clothes by the single tailor -- unless you could afford the bespoke. Everything from shirtwaists to wrought iron lamps was increasingly mass produced - under wretched conditions, too. Things – including buildings – that were once built to last a lifetime became cheap, disposable, and subject to the whimsy of fashion, sold via this new thing called “the catalog.”

William Morris' painting Le Belle Iseult (1868).

Unsurprisingly, this new way of living and working caused not a little discontent. This was the climate in which Karl Marx wrote Capital and Charles Dickens wrote A Christmas Carol. More specific to our interests, however, is a different dissenter and one of the most interesting practitioners of medievalism, the English polymath William Morris.

A lover of Arthurian legend and an admirer of the architect and design reformer John Ruskin, Morris was first trained in the office of architect G. E. Street, himself a die-hard Gothic Revivalist. From the very beginning, the Middle Ages can be found everywhere in Morris' work, from the rough-hewn qualities of the furniture he helped design to the floral elements and compositions of the art nouveau textiles and graphics he's most famous for -- which, it should be said, are reminiscent of 15th century English tapestries. In addition to his design endeavors, Morris was also a gifted writer and poet. His was a profound love for medieval literature, especially Norse sagas from Iceland. Some of these he even translated including the Volsunga Saga -- also a preoccupation of Wagner's. Few among us earn the title of polymath, but Morris' claim to it is undeniable. Aside from music, there really wasn't any area of creative life he didn't touch.

However, Morris' predilection for the medieval was not just a personal and aesthetic fascination. It was also an expression of his political rejection of the capitalist mode of production. As one of the founders of the English Arts & Crafts Movement, Morris called for a rejection of piecemeal machine labor, a return to handicraft, and overall to things made well and made with dignity. While this was and remains a largely middle class argument, one that usually leads down the road of ethical consumption, Morris was right that capitalism's failing of design and architecture did not just lie with the depreciated quality of goods, but the depreciated quality of life. His was the utopian call to respect both the object and the laborer who produced it. To quote from his 1888 essay called "The Revival of Architecture," Morris dreamed of a society that "will produce to live and not live to produce, as we do." Indeed, in our current era of AI Slop, there remains much to like about the Factory Slop-era call to take back time from the foreman's clock and once more make labor an act of enjoyable and unalienated creativity. Only now it's about things like writing an essay.

I bother to describe Morris at length here for a number of reasons. The first is to reiterate that medievalism's popularity was largely a response to socioeconomic changes. Additionally, since traditionalism - in Ludwig's time and in ours - still gets weaponized by right-wing losers, it's worth pointing out that not all practitioners of medievalism were politically reactionary in nature. However – and I will return to this later – medievalism, reactionary or not, remains inescapably nostalgic. Morris is no exception. While a total rejection of mass produced goods may seem quixotic to us now, when Morris was working, the era before mass industrialization remained at the fringes of living memory. Hence the nostalgia is perhaps to be expected. Unfortunately for him and for us, the only way out of capitalism is through it.

To return again to the big picture: whether one liked it or not, the old feudal world was done. Only its necrotic leftovers, namely a hereditary nobility whose power would run out of road in WWI, remained. For Ludwig purposes, it was a fraught political time in Bavaria as well. Bavaria, weird duck that it was, remained relatively autonomous within the new German Reich. Despite the title of king, Ludwig, much to his chagrin - hence the pathetic Middle Ages fantasizing - did not rule absolutely. His was a constitutional monarchy, and an embattled one at that. During the building of Neuschwanstein, the king found himself wedged between the Franco-Prussian War and the political coup masterminded by Otto von Bismarck that would put Europe on the fast track to a global conflict many saw as the atavistic culmination of all that already violent modernity. No wonder he wanted to hide with his Schwans up in the hills of Schwangau.

The very notion of a unified German Reich (or an independent Kingdom of Bavaria) was itself indicative of another development. Regardless if one was liberal or conservative, a king, an artist or a shoe peddler, the 19th century was plagued by the rise of modern nationalism. Bolstered by new ideas in "medical" “science,” this was also a racialized nationalism. A lot of emotional, political, and artistic investment was put into the idea that there existed a fundamentally German volk, a German soil, a German soul. This, however, was a universalizing statement in need of a citation, with lots of political power on the line. Hence, in order to add historical credence to these new conceptions of one’s heritage, people turned to the old sources.

Within the hallowed halls of Europe's universities, newly minted historians and philologists scoured medieval texts for traces of a people united by a common geography and ethnicity as well as the foundations for a historically continuous state. We now know that this is a problematic and incorrect way of looking at the medieval world, a world that was so very different from our own. A great deal of subsequent medieval scholarship still devotes itself to correcting for these errors. But back then, such scholarly ethics were not to be found and people did what they liked with the sources. A lot of assumptions were made in order to make whatever point one wanted, often about one's superiority over another. Hell, anyone who's been on Trad Guy Deus Vult Twitter knows that a lot of assumptions are still made, and for the same purposes.(2)

Meanwhile, outside of the academy, mass print media meant more people were exposed to medieval content than ever before. Translations of chivalric romances such as Wolfgang von Eschenbach’s Parzival and sagas like the Poetic Edda inspired a century’s worth of artists to incorporate these characters and themes into their work. This work was often but of course not always nationalistic in character. Such adaptations for political purposes could get very granular in nature. We all like to point to the greats like William Morris or Richard Wagner (who was really a master of a larger syncretism.) But there were many lesser attempts made by weaker artists that today have an unfortunate bootlicking je nais se quoi to them.

I love a minor tangent related to my interests, so here's one: a good example of this nationalist granularity comes from Franz Grillparzer’s 1823 pro-Hapsburg play König Ottokars Glück und Ende, which took for its source a deep cut 14th century manuscript called the Styrian Rhyming Chronicle, written by Ottokar Aus Der Gaul. The play concerns the political intrigue around King Ottokar II of Bohemia and his subsequent 1278 defeat at the hands of Grillparzer’s very swagged out Rudolf of Habsburg. Present are some truly fascinating but extremely obscure characters from 13th Holy Roman Empire lore including a long-time personal obsession of mine, the Styrian ministerial and three-time traitor of the Great Interregnum, Frederick V of Pettau. But I’m getting off-topic here. Let's get back to the castle.

The Throne Room at Neuschwanstein

For architecture, perhaps the most important development in spreading medievalism was this new institution called the "big public museum." Through a professionalizing field of archaeology and the sickness that was colonialist expansion, bits and bobs of buildings were stolen from places like North Africa, Egypt, the Middle East, and Byzantium, all of which had an enormous impact on latter 19th century architecture. (They were also picked up by early 20th century American architects from H. H. Richardson to Louis Sullivan.) These orientalized fragments were further disseminated through new books, monographs, and later photography.

Meanwhile, developments in fabrication (standardized building materials), construction (namely iron, then steel) and mass production sped things up and reduced costs considerably. Soon, castles and churches in the image of those that once took decades if not a century to build were erected on countless hillsides or in little town squares across the continent. These changes in the material production of architecture are key for understanding "why Neuschwanstein castle looks so weird."

Part of what gives medieval architecture its character is the sheer embodiment of labor embedded in all those heavy stones, stones that were chiseled, hauled, and set by hand. The Gothic cathedral was a precarious endeavor whose appearance of lightness was not earned easily, which is why, when writing about their sublimity, Edmund Burke invoked not only the play of light and shadow, but the sheer slowness and human toil involved.

This is, of course, not true of our present estate. Neuschwanstein not only eschews the role of a castle as a “fortress to be used in war” (an inherently stereotomic program) but was erected using contemporary materials and techniques that are simply not imbued with the same age or gravitas. Built via a typical brick construction but clad in more impressive sandstone, it's all far too clean. Neuschwanstein's proportions seem not only chaotic - towers and windows are strewn about seemingly on a whim - they are also totally irreconcilable with the castle's alleged typology, in part because we know what a genuine medieval castle looks like.

Ludwig's palace was a technological marvel of the industrial revolution. Not only did Neuschwanstein have indoor plumbing and central heat, it also used the largest glass windows then in manufacture. It's not even an Iron Age building. The throne room, seen earlier in this post, required the use of structural steel. None of this is to say that 19th century construction labor was easy. It wasn't and many people still died, including 30 at Neuschwanstein. It was, however, simply different in character than medieval labor. For all the waxing poetic about handiwork, I’m sure medieval stonemasons would have loved the use of a steam crane.

It's true that architectural eclecticism (the use of many styles at once) has a knack for undermining the presumed authenticity or fidelity of each style employed. But this somewhat misunderstands the crime. The thing about Neuschwanstein is that its goal was not to be historically authentic at all. Its target realm was that of fantasy. Not only that, a fantasy informed primarily by a contemporary media source. In this, it could be said to be more architecturally successful.

The fantasy of medievalism is very different than the truth of the Middle Ages. As I hinted at before, more than anything else, medievalism was an inherently nostalgic movement, and not only because it was a bedrock of so much children's literature. People loved it because it promised a bygone past that never existed. The visual and written languages of feudalism, despite it being a terrible socioeconomic system, came into vogue in part because it wasn't capitalism. We must remember that the 19th century saw industrial capitalism at its newest and rawest. Unregulated, it destroyed every natural resource in sight and subjected people, including children, to horrific labor conditions. It still does, and will probably get worse, but the difference is, we're somewhat used to it by now. The shock's worn off.

All that upheaval I talked about earlier made people long for a simplicity they felt was missing. This took many different forms. The rapid advances of secular society and the incursion of science into belief made many crave a greater religiosity. At a time when the effects of wage labor on the family had made womanhood a contested territory, many appeals were made to a divine and innocent feminine a la Lady Guinevere. Urbanization made many wish for a quieter world with less hustle and bustle and better air. These sentiments are not without their reasons. Technological and socioeconomic changes still make us feel alienated and destabilized, hence why there are so many medieval revivals even in our own time. (Chappell Roan of Arc anyone?) Hell, our own rich people aren't so different from Ludwig either. Mark Zuckerburg owns a Hawaiian island and basically controls the fates of the people who live there lord-in-the-castle-style.

Given all this, it's not surprising that of the products of the Middle Ages, perhaps chivalric romance was and remains the most popular. While never a real depiction of medieval life (no, all those knights were not dying on the behalf of pretty ladies), such stories of good men and women and their grand adventures still capture the imaginations of children and adults alike. (You will find no greater fan of Parzival than yours truly.) It's also no wonder the nature of the romance, with its paternalistic patriarchy, its Christianity, its sentimentality around courtly love, and most of all its depiction of the ruling class as noble and benevolent – appealed to someone like Ludwig, both as a quirked-up individual and a member of his class.

It follows, then, that any artist capable of synthesizing all these elements, fears, and desires into an aesthetically transcendent package would've had a great effect on such a man. One did, of course. His name was Richard Wagner.

In our next essay, we will witness one of the most astonishing cases of kitsch imitating art. But before there could be Neuschwanstein Castle, there had to be this pretty little opera called Lohengrin.

---

(1) If you want to get a head start on the Wagner stuff, I've been writing about the Ring cycle lately on my Substack: https://www.late-review.com/p/essays-on-wagners-ring-part-1-believing

(2) My favorite insane nationalist claim comes from the 1960s, when the Slovene-American historian Joseph Felicijan claimed that the US's democracy was based off the 13th century ritual of enthronement practiced by the Dukes of Carinthia because Thomas Jefferson owned a copy of Jean Bodin's Les six livres de la Republique (1576) in which the rite was mentioned. For more information, see Peter Štih's book The Middle Ages Between the Alps and the Northern Adriatic (p. 56 for the curious.)

If you like this post and want more like it, support McMansion Hell on Patreon for as little as $1/month for access to great bonus content including a discord server, extra posts, and livestreams.

Not into recurring payments? Try the tip jar! Student loans just started back up!

5K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Upright Harp Piano by F. Beale & Co., Musical Instruments

Medium: Mahogany, paint, gilding, cast iron, paint, silk, ivory, ebony, glaze

Gift of Mrs. Greenfield Sluder, 1944 Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY

http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/504396

216 notes

·

View notes

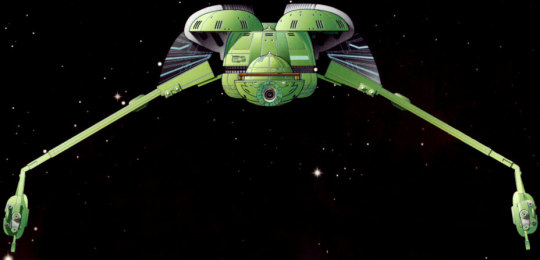

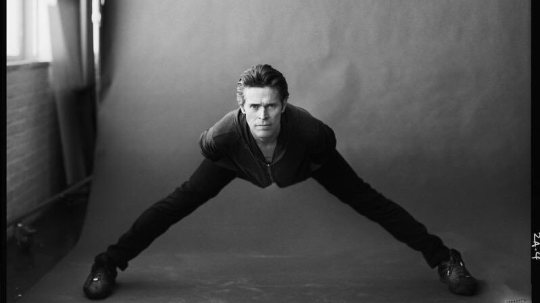

Text

Utterly thrilled that Williem Dafoe has been cast as the Klingon Bird of Prey

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

Anthony Roth Costanzo, star of the Met’s upcoming production of Akhnaten, liked a comment of mine on Facebook showing the setup of the tech elements of the opera from the Met’s public page and I’m loving it

This one specifically

121 notes

·

View notes