Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

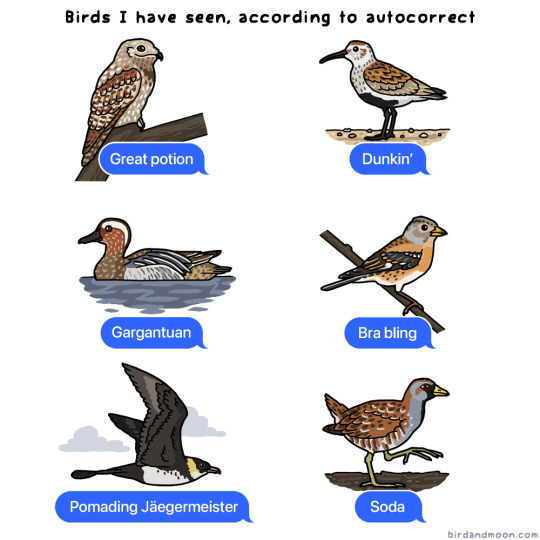

Birds I have seen, according to autocorrect.

14K notes

·

View notes

Text

The epoch that began with what we’re used to calling the “Age of Exploration” was marked by so many things that were genuinely new — the rise of modern science, capitalism, humanism, the nation-state — that it may seem odd to frame it as just another turn of a historical cycle. [… ]

The era begins around 1450 with a turn away from virtual currency and credit economies and back to gold and silver. The subsequent flow of bullion from the Americas sped the process immensely, sparking a “price revolution” in Western Europe that turned traditional society upside-down. What’s more, the return to bullion was accompanied by the return of a whole host of other conditions that, during the Middle Ages, had been largely suppressed or kept at bay: vast empires and professional armies, massive predatory warfare, untrammeled usury and debt peonage, but also materialistic philosophies, a new burst of scientific and philosophical creativity — even the return of chattel slavery. It was in no way a simple repeat performance. All the Axial Age pieces reappeared, but they came together in an entirely different way.

The 1400s are a peculiar period in European history. It was a century of endless catastrophe: large cities were regularly decimated by the Black Death; the commercial economy sagged and in some regions collapsed entirely: whole cities went bankrupt, defaulting on their bonds; the knightly classes squabbled over remnants, leaving much of the countryside devastated by endemic warfare. Even in geopolitical terms Christendom was staggering, with the Ottoman Empire not only scooping up what remained of Byzantium but pushing steadily into central Europe, its forces expanding on land and sea.

At the same time, from the perspective of many ordinary farmers and urban laborers, times couldn’t have been much better. One of the perverse effects of the bubonic plague, which killed off about one third of the European workforce, was that wages increased dramatically. It didn’t happen immediately, but this was largely because the first reaction of authorities was to enact legislation freezing wages, or even attempting to tie free peasants back to the land again. Such efforts were met with powerful resistance, culminating in a series of popular uprisings across Europe. These were squelched, but the authorities were also forced to compromise. Before long, so much wealth was flowing into the hands of ordinary people that governments had to start introducing new laws forbidding the lowborn to wear silks and ermine, and to limit the number of feast days, which, in many towns and parishes, began eating up one-third or even half of the year. The fifteenth century is, in fact, considered the heyday of Medieval festive life, with its floats and dragons, maypoles and church ales, its Abbots of Unreason and Lords of Misrule.

Over the next centuries, all this was to be destroyed. In England, the festive life was systematically attacked by Puritan reformers; then eventually by reformers everywhere, Catholic and Protestant alike. At the same time its economic basis in popular prosperity dissolved.

Why this happened has been a matter of intense historical debate for centuries. This much we know: it began with a massive inflation. Between 1500 and 1650, for instance, prices in England increased 500 percent, but wages rose much more slowly, so that in five generations, real wages fell to perhaps 40 percent of what they had been. The same thing happened everywhere in Europe.

Why?

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ag areas with drought kill weeds more because of their water consumption costs than crop competition purposes. weeds are thirsty too

The world's most unwanted plants help trees make more fruit

44K notes

·

View notes

Video

Another busy work week, so I am lagging a bit behind with photos but here’s a Flying squirrel to hold you over 😁 He’s been on camera last last October so it was a bit surprising to see him.

169 notes

·

View notes

Photo

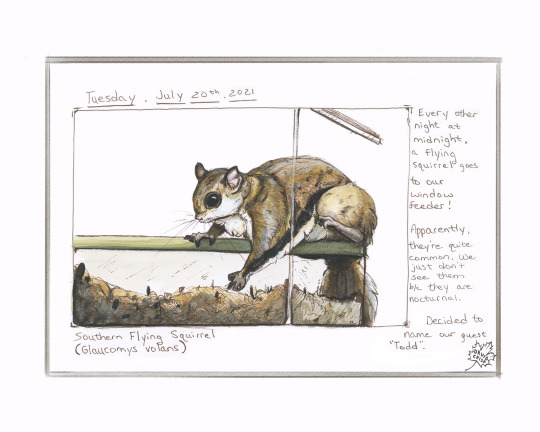

The study and final sketch of a flying squirrel that regularly visits our window feeder!

I couldn’t get any decent pictures of him to fully base a drawing off of… I also didn’t want to turn on the balcony light, since they’re nocturnal. So, I used my lower quality photos for the poses and several reference images to get the colors, fur, and details down.

I think I went a bit overboard with the watercolor pencils to give his fur some texture (in the final sketch), but I know I’m getting closer to finding the right balance!

All in all, I’m pretty happy with how it turned out! And it’s nice to have a representation of him in my nature journal!

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

i know a place! *brings you into my arms and hugs you*

110K notes

·

View notes

Text

A flying squirrel got into my folks house. 🐿

79 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Squirrel Appreciation Day reminds us to enjoy these adorable, scampering animals respectively! Our Flying Squirrels at OBC will be getting some extra love and gratitude today!

321 notes

·

View notes