The Journey of a PhD research in local future materials and territories

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

EAD 2019 - PhD event journal

Ritrovamenti

issuu

0 notes

Text

Opere d’arte come supporto ai contenuti

“Ci è sembrato che una rassegna di fonti iconografiche di tutt’altra origine, qual è quella dell’espressione artistica potesse - con quella rappresentatività e con quella intuizione del << tipico>>, che dell’opera d’arte costituisce, appunto, una nota saliente – fornirci un materiale illustrativo non solo più suggestivo per il lettore, ma anche più pertinente al carattere e ai limiti della nostra indagine. La nostra rassegna di queste fonti iconografiche condotta su oltre duecentomila riproduzioni di opere d’arte (o di loro dettagli) di ogni età, è stata, crediamo, relativamente esauriente, e si è rilevata per noi, comunque, sotto molti aspetti, assai istruttiva. Essa ci ha consentito di selezionare, oltre che abbondanti materiali relativi alla storia degli allevamenti, delle culture, delle tecniche e del lavoro agricolo nel nostro paese, alcune migliaia, almeno, di particolari iconografici relativi al più specifico oggetto di questa nostra indagine: e ci duole soltanto che il desiderio dell’editore, e nostro, di rendere questo volume accessibile ad un più largo pubblico di lettori, non aggravandone eccessivamente il costo; non ci abbia consentito di riprodurre qui che una parte relativamente piccola di questo materiale illustrativo. “

Testo tratto da Sereni, E., Storia del paesaggio agrario italiano, Editori Laterza, 2017 (prima edizione 1961), Roma.

0 notes

Text

MAKING/CRAFTING/DESIGNING: PERSPECTIVES ON DESIGN AS A HUMAN ACTIVITY Design Theory Symposium, 10–12 February 2011

STEPHEN DUNCOMBE New York UniversityArt of the Impossible: The Politics of Designing UtopiaA growing minority of critically engaged activists, artists, and designers have been abandoning the unveiling, revealing, and truth-telling function of political art and protest for a boldly utopian practice. These artists understand that the political crises of today’s world stem not from lack of access to the truth, nor will they be resolved by more criticism. The political problem par excellence is one of atrophied imagination. But what is so interesting about these artists’ imaginative designs is the nature of their utopias: they are patently and consciously absurd. They propose to make things that can never be made. But it is in this very absurdity that the political power lies. This creative practice opens up space for the viewer to question the present, without then short-circuiting this moment of democratic imagination with a realizable blueprint of the future. Simply, the design asks: What If?, without answering: This is What! Drawing upon a range of art and media examples from Thomas More’s 16th century utopia to absurd designs for urban futures to the Yes Men’s recent “Special Edition” of the New York Times, Duncombe will critically explore the creative terrain of impossible utopias that constitute a type of dreampolitik.

LUCY KIMBELL University of Oxford / Fieldstudio, London

Designing Future Practices

What is it that designers are designing when they do design? This paper tries to answer this question by reviewing developments in design theory and practice and combining them with work in the social sciences that attends to practices. In recent years, histories and theories of design have exhibited a social turn, at the same time that professional designers have moved into designing services, systems and interactions within commercial and public contexts. Within the emerging field of professional service design, for example, designers attend to the arrangements of material, digital, and people-based “touchpoints” with which consumers and customers engage as part of services that are orchestrated by organizations. Some designers are involved with helping redesign public services such as healthcare and education and within contexts such as international peace and security. A debate remains, however, about whether designers are still primarily concerned with designing “stuff,” what designers do that is different to what managers do, and whether both designers and managers are ready to understand the roles they and their designs play in constituting social worlds, at a time when climate change is forcing us to ask questions about how designers have contributed to particular kinds of consumption activity (Fry 1999, 2009). To explore these questions, the paper shifts the conversation away from oppositions between the material and the non-material to consideration of practices. Theories of practice (eg Schatzki 2001; Reckwitz 2002) avoid such dualisms by understanding social worlds as created through interactions between minds, bodies, things, structure, agency, and process. The opportunity for designers is to understand that what they are designing as future practices, which include arrangements of things, people, and symbolic structures, and within which both the things and the people play important roles in constituting the meaning and effects of designs. Drawing on work by Suchman (2003), Tonkinwise (2003), and others, the paper proposes key concepts to help orient understanding of practices including relationality, temporality, and accountability. This expanded notion of design has implications for design practice, research, and education.

Fry, Tony. 1999. A New Design Philosophy. An Introduction to Defuturing. Sydney: UNSW Press. Fry, Tony. 2009. Design Futuring: Sustainability, Ethics and New Practice. Oxford: Berg. Reckwitz, Andreas. 2002. Towards a Theory of Social Practices: A Development in Culturalist Theorizing. European Journal of Social Theory 5, no. 2: 243–63. Schatzki, Theodore R. 2001. Introduction: Practice Theory. In The Practice Turn in Contemporary Theory, ed. Theodore E. Schatzki, Karin Knorr Cetina, and Eike von Savigny. London: Routledge. Suchman, Lucy. 2003. Located Accountabilities in Technology Production, Lancaster: Centre for Science Studies, Lancaster University. Tonkinwise, Cameron. 2003. Interminable Design: Techne and Time in the Design of Sustainable Service Systems. Paper presented at the 5th European Academy of Design Conference, Barcelona.

http://www.makingcraftingdesigning.com/reviews.htm

1 note

·

View note

Text

Dalla progettazione del prodotto industriale al tutto

“Con il passaggio da un’economia dei consumi a un’economia della sovrapproduzione, e la conseguente ridistrubuzione degli scenari produttivi internazionali, soprattutto nei paesi come il nostro a bassa vocazione industriale e forti radici artigianali, la figura del designer come tecnico del processo industriale è entrata in crisi e il design ha progressivamente mutato i suoi ambiti configurandosi non più come scienza settoriale ma come disciplina ampia alla base di approfondimenti teorici e nuovi processi organizzativi. Il design ormai non è più solo progetto del prodotto industriale ma una disciplina in continua evoluzione che applica il processo progettuale alla costruzione di oggetti quanto alla costruzione di scenari, ‘capace di connettere saperi diversi, dalle scienze tecniche alle humanities, e di sviluppare tematiche ad ampio raggio (Germak, 2008)’”.

Testo tratto da Follesa, S., Design e Identità. Progettare per i luoghi, Franco Angeli, 2013, Milano, p. 78.

BIBLIOGRAFIA

Germak, C. (a cura di), L’uomo al centro del progetto, Allemandi, Torino, 2008.

0 notes

Text

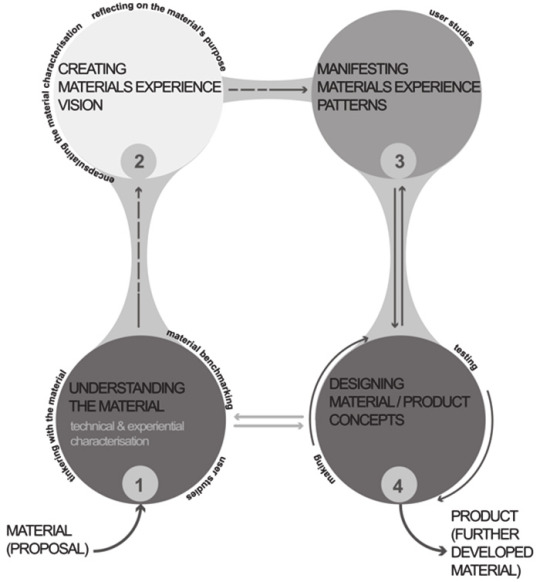

Materials Driven Design (MDD)

(Karana, E., 2015)

“A method to facilitate a design process in which materials are the main drivers.

We ground our discussion on many disparate but interconnetted sources: existing literature and theories on materials experiences (Giaccardi & Karana, 2015; Karana et al., 2014; Karana, Hekkert, & Kandachar, 2008); ingredients of experience design (Desmet, Hekkert, & Schifferstein, 2011); methodology for material- centered interaction design research (Wiberg, 2014); the material learning that was carried out at the Bauhaus (Wick, 2000) and tinkering with materials in art, craft, and design. [..]

Figure illustrates the MDD Method with four main action steps presented in a sequential manner as: (1) Understanding The Material: Technical and Experiential Characterization (tinkering with the material; material benchmarking; user studies), (2) Creating Materials Experience Vision (The Materials Experience Vision expresses how a designer envisions a material’s role in creating/contributing to functional superiority (performance) and a unique user experience when embodied in a product, as well as its purpose in relation to other products, people, and a broader context (i.e., society and planet), (3) Manifesting Materials Experience Patterns (RQ: What are the interrelationships between the created material experience vision and the formal qualities of materials and products?), (4) Designing Material/Product Concepts. […]MDD starts with a material (or a material proposal) and ends with a product and/or further developed material. […] The journey of the designer from tangible to abstract and then from abstract back to tangible.

3 starting scenarios: [Scenario 1]

Designing with a relatively well-known material,

[Scenario 2]

Designing with a relatively unknown material,

[Scenario 3]

Designing with a material proposal with semi-developed or exploratory samples”

Text from Karana, E., Barati, B., Rognoli, V., & Zeeuw van der Laan, A. (2015). Material driven design (MDD): A method to design for material experiences. International Journal of Design, 9(2), 35-54.

(Valentina notes)

How to apply and adapt MDD method to a specific local context in order to propose a future material culture?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Desmet, P., Hekkert, P., & Schifferstein, R. (2011). Introduction. In P. Desmet & R. Schifferstein (Eds.), From floating wheelchairs to mobile car parks: A collection of 35 experience-driven design projects (pp. 4-12). Den Haag, the Netherlands: Eleven.

Giaccardi, E., & Karana, E. (2015). Foundations of materials experience: An approach for HCI. In Proceedings of the 33rd SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 2447-2456). New York, NY: ACM.

Itten, J. (1975). Design and form: The basic course at the Bauhaus and later. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Hekkert, P., & van Dijk, M. (2011). Vision in design: A guidebook for innovators. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: BIS.

Karana, E., Hekkert, P., & Kandachar, P. (2008). Materials experience: Descriptive categories in material appraisals. In Proceedings of the Conference on Tools and Methods in Competitive Engineering (pp. 399-412). Delft, the Netherlands: Delft University of Technology.

Karana, E., Pedgley, O., & Rognoli, V. (2014). Materials experience: Fundamentals of materials and design. Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Tung, F. W. (2012). Weaving with rush: Exploring craft-design collaborations in revitalizing a local craft. International Journal of Design, 6(3), 71-84.

Wiberg, M. (2014). Methodology for materiality: Interaction design research through a material lens. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 18(3), 625-636.

Wick, R. K. (2000). Teaching at the Bauhaus. Stuttgart, Germany: Hatje Cantz.

0 notes

Text

About DIY materials

“In recent years many initiatives based on DIY practices (Fox, 2014) have flourished around the world. These also concerned professional design and not just the works of amateurs. In fact, the designer took the opportunity to acquire control of the entire design process by developing material artefact autonomously. Kotler (1986) defines Do-It-Yourself materials as an activity in which individuals employ raw and semi-raw materials and parts to produce, transform or reconstruct materials goods, including those obtained from the natural environment. When designers faced this growing trend related to self-production and focused on the material dimension, a new class of materials was born, DIY materials (Rognoli et al, 2015)”

Text extracts from Rognoli, V., Alaya Garcia, C., Pollini, B., DIY Recipes: Ingredients, process and material qualities in Material Designers. Boosting talent toward circular economies, 2021, p. 28.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fox S. (2014). Third Wave Do-It-Yourself (DIY): potential for prosumption, innovation, and entrepreneurship by local populations in regions without industrial manufacturing infrastructure. Technology in Society n.39, pp.18–30.

Kotler P. (1986). The Prosumer Movement: a New Challenge For Marketers. NA - Advances in Consumer Research, vol. 13, pp. 510-513.

Rognoli V., Bianchini M., Maffei S., Karana E. (2015). DIY Materials. Special Issue on Emerging Materials Experience. In: Virtual Special Issue on Emerging Materials Experience, Materials & Design, vol. 86, pp. 692–702

0 notes