Audio

Gentle jazz filters in to where I sit perched up on the second ledge from the bottom. The Leubas must be near. Ah, yes, here they come, gently padding across the hardwood with their loving eyes scanning the many literary volumes and works of art spread throughout the room...

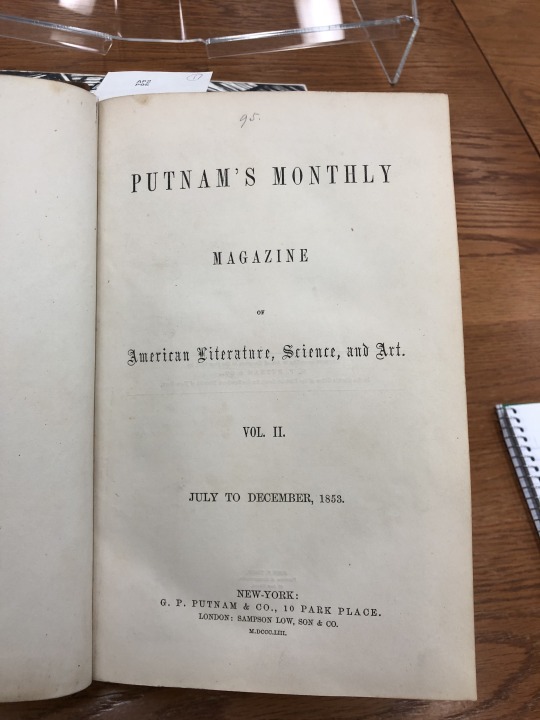

My, my, forgive me for my rudeness in not properly introducing myself...I am out of practice in this art as I mainly converse only with my fellow literary friends in the Leuba household. I am the Leuba’s (more on them later) 1855 volume of Putnam’s Monthly Magazine of American Literature, Science, and Art published in the Northern United States. Though I may not be of the same build as my grandfather, a monthly magazine as was the original format of Putnam’s Monthly (figures), I still contain all of the same pieces - just put together in an 1855 yearly volume. My pages are wrinkled, my coloring a fading tan and black. My weight, I dare to hesitantly reveal, is greater than that of the average novel...

Suddenly, but slowly and with a sure hand, I am being pulled from my resting spot on the second shelf. Ouch! Can you hear my spine cracking?

Again, I will have to ask for your forgiveness...My loyal companion two years my senior is pictured here instead of me (as I’m sure many of you will understand, it was a bad hair day). Although he contains material from the 1853 volume of Putnam’s Monthly, we are almost identical in form and layout!

The stories contained within my pages, some true and some not, highlight American thought during the middle of the nineteenth century - a time in which tensions regarding matters of race and slavery ran high. Americans and foreigners alike were grappling with these issues which understandably gave way to a desire to make known their opinions to the greater public.

“Topics of national and general interest, or relating to the public welfare, will be discussed when there is occasion, with freedom...”

-Publisher’s note in Putnam’s Monthly

It is here where we finally arrive at our destination on my page 353. You, reader, have been waiting oh so patiently, for aren’t we ultimately setting out to contextualize “Benito Cereno?” This story, “Benito Cereno,” was written by Herman Melville and tells the tale of sea captain Amasa Delano and his encounter with a peculiar ship carrying white sailors and African slaves - with special focus put on the ship’s captain Benito Cereno and his enslaved African companion Babo. Even though the story finds its basis in the writings of the real captain Amasa Delano, it diverges from the true happenings as Melville changes the character of Delano and the narrator and weaves a story, providing much more description. Overall, in making this change, Melville is able to intentionally represent slaves as being intelligent, strategic, and real people (especially in the case of Babo). Therefore, it takes on an abolitionist viewpoint and allows readers to fully see the humanity of African slaves without having radical anti-slavery writings thrust at them.

Those coming across “Benito Cereno” would no doubt also have to be aware of the other articles contained in my volume. It is serialized in Putnam’s Monthly, not a stand alone work and as such, we can look to the articles surrounding it to perhaps glean more about what other writers and publishers of the time were thinking about slavery and race. As you peruse my pages, you will find poems attributed to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, an ardent abolitionist, an article entitled “The Kansas Question,” and multiple other texts either directly or indirectly speaking on the question of slavery. There is a heavy emphasis on anti-slavery ideals, and even those writings not explicitly containing material about race or slavery can be applied to the emancipation cause if a reader was of that mindset.

Readers of Putnam’s Monthly would have received “Benito Cereno” as a way for Melville to subtly expose the status of slaves in a way that would further the abolitionist agenda without being an incendiary work that would cause a stir among the already divided states.

Remember the Leubas I referred to above? I told you we would come back to them! They, Walter and Martha, collect books, artwork, prints, letters, and other notable works from a multitude of remarkable figures. You know by now that I am a member of the extraordinary Leuba collection and contain many texts from writers holding anti-slavery opinions. But what about my other literary friends I spoke of earlier? What do their pages hold relating to matters of race and slavery, and what does this say about the Leubas?

The mark myself, as well as the others, proudly bear as parts of the Martha and Walter Leuba collection is pictured below.

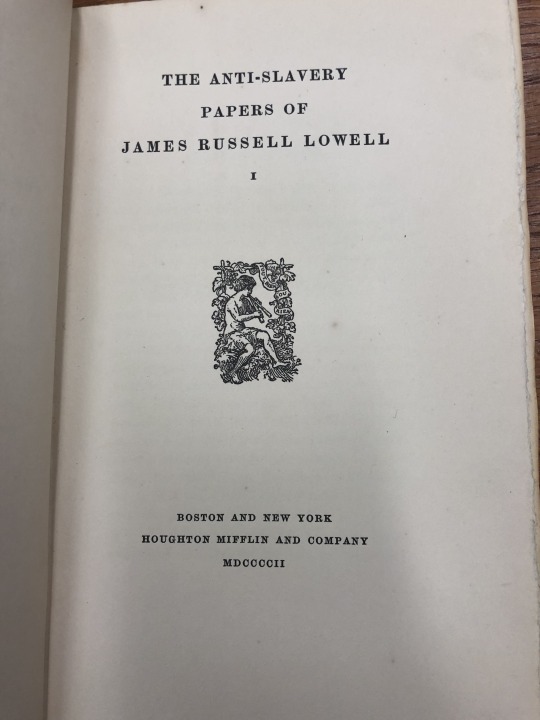

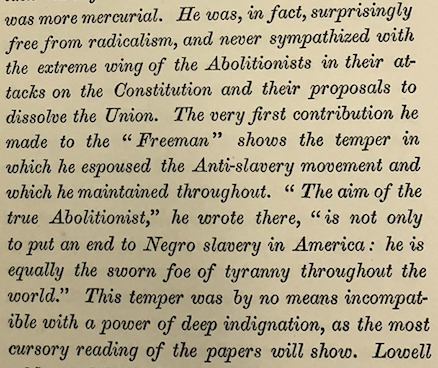

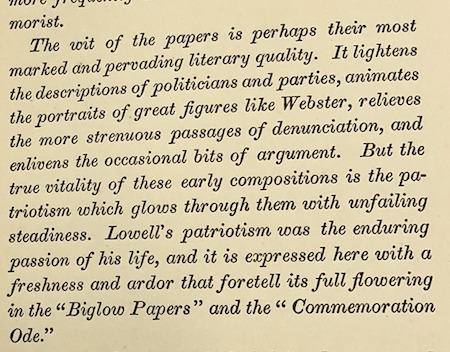

One good friend of mine is a copy of the Anti-Slavery Papers of James Russell Lowell volume I. He and his brother, volume II, comprise the set the Leubas own.

James Russell Lowell, as you can read more about in the two images below, was a writer who really became a part of the anti-slavery movement during the 1840′s. He penned many, many, poems, as well as articles, in defense of abolitionism and was the chief editorial writer for numerous anti-slavery / abolitionist newspapers, including the National Anti-Slavery Standard and the Pennsylvania Freeman. Even with his witty and slightly racy language, he managed to become a significant abolitionist.

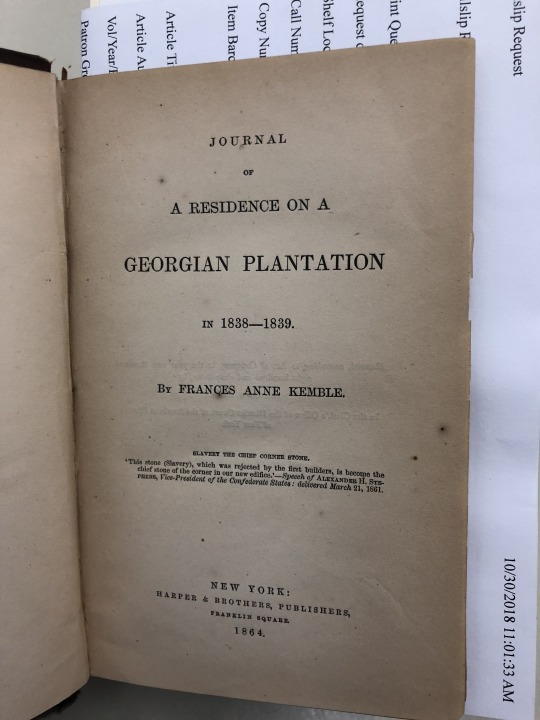

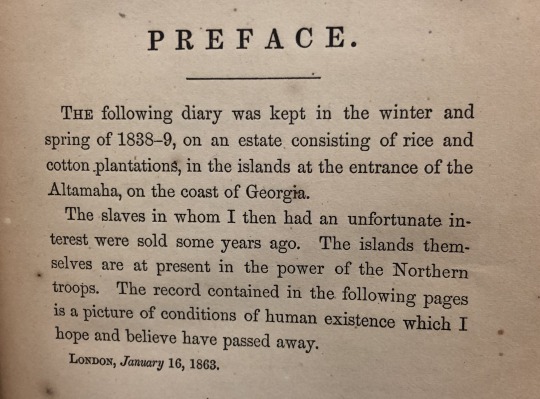

Yet another close friend of mine in the Leuba collection contains the personal writings of “Fanny” Kemble in what is considered the “closest, most detailed look at plantation slavery ever recorded by a white northern abolitionist” (PBS).

This journal was written during the time Fanny spent on the Georgian rice and cotton plantations actually owned by her husband, Pierce Butler. At the time of their marriage, she was not aware of his great dealings in the slave trade and ended up divorcing him after realizing he would never change his pro-slavery views.

Fanny’s writings as a whole show that she is so blatantly positioned in complete opposition of anything to do with slavery. She passionately exposes the inhumanity and horrors faced by the slaves and continued to stand firm in her abolitionist ways.

Though these are only two closer looks at fellow books in the Leuba collection, there are many more dealing with the same topics of race and slavery from the same perspective of being directly against them. My personal opinion, which I hope can now become yours as well, is that Martha and Walter greatly appreciate the efforts of abolitionist writers and their works during the 1800′s. Their aim is to preserve these books of significance for future generations. It can also be said that the Leubas would read my “Benito Cereno” pages and think about slavery through an abolitionist lens while understanding the African slaves truly were intelligent, worthy human beings.

Works Cited

-images were taken of books from the Special Collections room at Hillman Library

"Fanny Kemble and Pierce Butler." PBS Africans in America, WGBH, www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/

4p1569.html.

"James Russell Lowell." Poetry Foundation, www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/james-russell-lowell.

"Longfellow, Slavery and Abolition." National Park Service, 12 Jan. 2018, www.nps.gov/long/learn/

historyculture/longfellow-slavery-and-abolition.htm.

Melville, Herman. "Benito Cereno." Putnam's Monthly Magazine, vol. 6, 1855, pp. 353+.

"Putnam's Magazine." Wikipedia, 20 Jan. 2018, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Putnam%27s_Magazine. Accessed 3

Nov. 2018.

"Walter and Martha Leuba Papers." ULS Digital Collections, digital.library.pitt.edu/collection/

walter-martha-leuba-papers. Accessed 2 Nov. 2018.

1 note

·

View note