Text

An Introduction to Robert Devereux

“Bye bye 7.6 million dollars worth of modern and Contemporary British art!” the gavel seemed to say as it hit the auction block at Sotheby’s London from November 3-4, 2010 when art collector Robert Devereux decided to sell his collection and use the proceeds to start The African Arts Trust, a charity that supports arts organizations in Africa or arts initiatives in Africa that need more funding. Devereux could have used the funds from the sale to acquire Contemporary African art for himself or to support individual artists; however, those efforts would have been what luxury men’s style website Mr. Porter calls “indulgent.” Instead, Devereux lends a hand to African organizations that are already pursuing better funding for artists and helping support their careers. That way, Devereux also avoids having to make a decision on which artists have the talent and determination to make a career and a living out of art. Devereux does still have his own collection of Contemporary African art that he has been acquiring since around 2002-2003, although the funding for that has come from the businessman himself and not directly from the Sotheby’s sale.

Born and bred Englishman Devereux studied History at Cambridge University and then went on to work in publishing before eventually working for Richard Branson, the British Virgin media mogul and Devereux’s future brother-in-law. At Virgin, Devereux made his fortune and began collecting Contemporary art in the late 1970s and early 1980s when his wife at the time, Vanessa Branson, opened up a gallery in Notting Hill, London. At age 40, during what he describes as a “midlife crisis,” Devereux threw on a backpack and left for East Africa, falling in love with the continent (at least what he saw of it) and its local artists. Devereux felt he had the opportunity to make a difference by supporting the careers of artists in Africa who live in places where there is hardly an infrastructure of the arts, including lack of government interest in funding creative endeavors. “All artists have to struggle, but there are not many places harder than Africa,” Devereux explains.

In 2010, using the money earned from the Sotheby’s London auction of his contemporary British art collection, Devereux set up The African Arts Trust. The mission of the trust, as stated on its website, is to “act as a catalyst for the emergence and growth of locally managed and sustainable contemporary visual art organizations in Africa.” Among the range of support and services that these grassroots organizations provide for artists are studios, internet and gallery space. One of the organizations that has benefited from the trust is an organization known as Kuona Trust, a center for visual arts that provides exhibition space and studios in Nairobi. Kuona Trust was at one point run by Danda Jaroljmek, who serves as an administrator for The African Arts Trust and brings her expertise on the East African art scene to Devereux’s charitable organization. So far, the charity has done things like help fund a residency and exhibition for a Congolese artist at Gasworks Gallery in London and pay for the transport of three African artists to the Dak’Art Biennale in Senegal.

Robert Devereux attends the Soho House Kibera Project at Mount Street Galleries on October 4, 2011 in London, England. Source: http://www.zimbio.com/photos/Robert+Devereux/Soho+House + Kibera+Project/m3lwHdr86kk.

Devereux’s personal art collection of “art that is connected to the African continent,” as of 2017, includes around 500-600 works. However, the collector admits that he doesn’t know exactly how many works he has. The first public show of work from his collection opened in the United Kingdom at Cambridge, his alma mater, from February 25, 2017 to May 21, 2017. The exhibition, entitled Where the Heavens Meet the Earth, brings together more than 35 works from Devereux’s collection, which he calls the “Sina Jina Collection, named after the house he bought in Lamu, Kenya. The show featured art by names that someone who is familiar with Contemporary African art, at least - for example - who is selling at auction and at big-name galleries, would recognize, including: El Anatsui, Ruby Amanze, Romuald Hazoumé and Nandipha Mntambo. In terms of where he acquires works for his collection, the businessman says he looks to artists’ studios, auctions, galleries and art world professionals who show him work that inspires him to make a purchase. The Financial Times reports that Devereux has a preference for buying work on the primary market, because (among other factors) engagement with the artists invariably enhances his appreciation of their work.

Important to understanding who Devereux is as a collector is knowing that he does not like the term collector, and perhaps instead to be seen as a sort of custodian to the art he buys, which has less of a quotation of hoarding and not showing his art to the world. The reality is; however, that most of Devereux’s collection is in his home or in storage. The collector finds this situation unfortunate, and tries to make as many loans as possible.

The 2017 show at Cambridge is a good start for the collector in terms publicly displaying his works. The show itself, Devereux reveals, only displays a mere ten percent of his collection, making one wonder about the rest of his artwork. Since Where the Heavens Meet the Earth, critics have wondered when and if Devereux’s collection will return to the African continent and be displayed there - an idea the collector is open to and seems to be optimistic about. Speaking about where his collection will ultimately end up, Devereux said: “I would love to gift it to an institution, ideally to an African one.” In the meantime, Devereux has taken up various roles in the art world that help him guide the narrative of Contemporary African art, including serving on the African Acquisitions Committee at Tate as well as an adviser to 1-54 Contemporary African Art fair.

Bibliography:

BORGEN Magazine. “The African Arts Trust Celebrates Upcoming African Artists.” June 7, 2014. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.borgenmagazine.com/african-arts-trust-celebrates-upcoming-african- artists/.

Compton, Nick. “Mr Robert Devereux.” MR PORTER. October 15, 2013. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.mrporter.com/journal/journal_issue136/3#1.

Corbett, Rachel. “London Art Patron Robert Devereux on Finding Art’s Promise in Africa.” Artspace. October 16, 2013. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.artspace.com/magazine/interviews_features/how_i_collect/robert_devereux-51734.

Cummings, Basia Lewandowska. “From The Ground Up.” New African Magazine. September 18, 2013. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://newafricanmagazine.com/news-analysis/long-reads/from-the-ground-up/.

DandaJeroljmek.com. “Danda Jaroljmek.” Accessed November 4, 2018. https://dandajaroljmek.com/.

Downing College Cambridge. “When the Heavens Meet the Earth.” Accessed November 4, 2018. http://www.dow.cam.ac.uk/cultural-life/heong-gallery/past-exhibitions/when-heavens-meet-earth.

Enwonwu, Oliver. “Robert Devereux on the Magical and the Real.” Omenka Online. February 8, 2017. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.omenkaonline.com/robert-devereux-on- the-magical-and-the-real/.

Gleadell, Colin. “Dealers Snap Up Well-Estimated Works at Sotheby’s Devereux Sale.” ARTnews. November 16, 2010. Accessed November 4, 2018. http://www.artnews.com/2010/11/16/dealers-snap-up- well-estimated-works-at-sothebys-devereux-sale/.

Gosling, Emily. “Robert Devereux on what we can learn from the ‘anarchic’ spirit of African art and why painting will never die.” Creative Boom. March 24, 2017. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.creativeboom.com/features/contemporary-african-art/.

Harris, Kitty. “Founder of The African Arts Trust, Robert Devereux on the rise of contemporary art collectors.” LUX. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.lux-mag.com/founder-of-the-african-arts-trust-robert-devereux-on-the-rise-of-contemporary-art-collectors/

Shaw, Anny. “Will former Frieze chairman Robert Devereux’s collection of art from Africa and the diaspora return to the continent?” The Art Newspaper. January 17, 2017. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/will-former-frieze-chairman-robert-devereuxs-collection-of-art-from-africa-and-the-diaspora-return-to-the-continent

The African Arts Trust. “Home.” Accessed November 4, 2018. http://www.theafricanartstrust.org/.

Wrathall, Claire. “Why Robert Devereux sold his modern British art to buy African work.” Financial Times. March 3, 2017. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.ft.com/content/3930ecce-fa7a-11e6-bd4e-68d53499ed71.

Photo at top: Robert Devereux at the Kuona Trust, Centre for Visual Arts, Nairobi © Sven Torfinn. Source: https://www.ft.com/content/3930ecce-fa7a-11e6-bd4e-68d53499ed71.

#contemporary african art#contemporary art#contemporary art blog#african art#african contemporary art#artists on tumblr#art blog#art blogger#robert devereux#art collectors#collectors#art collector#devereux#robertdevereux

1 note

·

View note

Text

An Introduction to Jochen Zeitz

In Cape Town, South Africa sits a museum 9,500 square feet in size entirely devoted to Contemporary African art. All of the art hanging in the gigantic space - known as Zeitz MOCAA (Museum of Contemporary Art Africa) is from the collection of one single man: Jochen Zeitz, one of the top 200 most important art collectors, according to the prestigious annual ARTnews list. This blog post aims to help one get acquainted with Zeitz and understand his motive for collecting, because, by amassing a collection of Contemporary African art, and then funding a museum on the African continent to share this art with the world, Zeitz has helped bring the stories of African artists to a wider audience.

Zeitz, who was born in Germany, first came to Africa on safari in 1989. After that first trip, he tried to travel around the continent as much as he could. “When the German entrepreneur Jochen Zeitz fell in love with Africa, he took the passion seriously. He bought a 50,000-acre ranch in Kenya,” reports The Telegraph. Upon buying his ranch in Kenya in 2003, Zeitz even learned Swahili - allowing him to communicate with Kenyans in the country’s other official language besides English. Since then, Zeitz has become the Honorary Warden of Kenya, an award bestowed on him by the Kenya Wildlife Service. According to his wife, television and movie producer Kate Garwood, Zeitz “is in Kenya whenever possible.” This collector’s involvement and deep appreciation for African culture not only drives his art collecting, but speaks to his motives and his genuine desire to share Africa’s stories with the world through supporting the visual arts.

In 1993, Zeitz became the youngest CEO in German history to head a public company when he was appointed to the top position at Puma, a company that at that point was nearing bankruptcy. The businessman was able to turn the company around into becoming one of the top three brands in the sporting goods industry and generating over $4 billion in sales. Zeitz’s strategy for turning around the sneaker company was to invest in African sports teams, showing off Puma’s adventurous spirit. Through his forays into the continent as a businessman, Zeitz became fascinated by Africa and all of the creativity its people had to offer. In an interview with popular art collecting website Larry’s List, Zeitz recalls that he was surprised to see that Contemporary African art was not more popular on the art market and that there were not enough opportunities where the creativity that he experienced in Africa could be presented.

Determined to create those opportunities for the creativity of Africans to be expressed, Zeitz began collecting art from artists that he met and encountered around the time when he became a resident of Kenya in 2003. At this time in the early 2000s, Zeitz was just buying pieces here and there with no big purpose other than to have art around him in his private life. Although the businessman actually started his art collecting career in the 1990s while he was living in New York by collecting Pop artists like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, by the end of the first decade in the new millennium, Zeitz would focus his collection specifically on Contemporary African art.

In 2003, Zeitz hired Mark Coetzee, who was born in South Africa, and at the time the curator of the Rubell Family Collection in Miami, to oversee Puma’s creative platform. In 2008, Coetzee curated an exhibition called 30 Americans, a show that featured exclusively African-American artists and was sponsored by Puma for the Rubell Collection. Upon seeing the show, Zeitz said he wanted to know more and went for pizza with Mark to have a quiet conversation. The two ended up talking about why Africa didn’t have a major contemporary art museum, and Mark shared his vision to go back to South Africa and start one. Zeitz was intrigued. The Telegraph reports that Coetzee left the Rubell Foundation in 2011 to start working with Zeitz on creating their dream of the museum for Contemporary African art, and cites 2008 as a turning point for Zeitz when he turned his art collecting away from more “predictable choices” to specifically art made in Africa or by Africans from 2000 onward.

Robb Report, the American and English luxury-lifestyle magazine, explains that Zeitz started buying works under the guidance of curator Mark Coetzee and dove headfirst into his new project, buying a lot of work in a very short period of time. At the 2013 Venice Biennale alone, for example, the entrepreneur bought 85 works. By 2014, Robb Report explains, the duo had assembled the leading collection of works from contemporary African artists practicing in their native countries and elsewhere in the world. Zeitz unveiled a portion of his collection at his private Kenyan ranch, inviting guests to stay and taking notice of how people would react to the art on display. Three years later, Zeitz’s entire collection found a home in the Zeitz MOCAA, while he continues to acquire new works and support the artists who inspire him.

Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa (Zeitz MOCAA) describes itself (according to its website and mission statement) as: “a public not-for-profit contemporary art museum which collects, preserves, researches, and exhibits twenty-first-century art from Africa and its Diaspora; hosts international exhibitions; develops supporting educational and enrichment programmes; encourages intercultural understanding; and guarantees access for all.” ARTnews writer Gemma Sieff elaborates on the museum’s statement and explains: “The museum’s mission is to reposition Africa as an authority on its own 54 countries and global issues beyond—as a continent no longer plundered by outsiders and force-fed an exogenous narrative, but that is, increasingly, telling its own story.”

Zeitz MOCAA, Source: https://insideguide.co.za/cape-town/things-to-do/zeitz-mocaa/.

As of now, the museum’s collection is mostly art from Zeitz‘s private collection (which is on lifetime loan); however, the museum has begun to also establish its own permanent collection through purchases and gifts. The museum has over 100 galleries and 6,500 square feet of exhibition space - which is inspiring when you think about all the Contemporary African art that is, and could be, shown there. When the museum opened in 2017, the inaugural exhibitions included works by Nicholas Hlobo, an artist from South Africa represented by the prestigious Lehmann Maupin gallery, El Anatsui, extremely well-known artist from Ghana whose works feature in the collection of important art institutions worldwide, and Cyrus Kabiru, creative photographer and hopeful rising star from Kenya. Speaking about seeing his collection in the museum, Zeitz reveals in an official Zeitz MOCAA press release: “I built my collection with a museum in Africa always in mind––the fact that these works will now be accessible to all is a very emotional thing for me personally and, ultimately, gives the art true purpose.”

Photo at top: Jochen Zeitz. Source: https://www.ft.com/content/5c3531e0-4947-11e8-8c77-ff51caedcde6.

Bibliography:

ARTnews. “2017 Top 200 Collectors.” Accessed November 4, 2018. http://www.artnews.com/top200year/2017/.

Ashton, James. “Jochen Zeitz: The businessman who uses his millions to change opinions on climate change.” The Independent. April 5, 2015. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.independent.co.uk/environment/climate-change/jochen-zeitz-the-businessman-who-uses-his-millions-to-change-opinions-on-climate-change-10157482.html

Caradonio, Jackie. “How Jochen Zeitz Created the World’s Biggest Museum of Contemporary African Art.” Robb Report. August 17, 2017. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://robbreport.com/shelter/art-collectibles/jochen-zeitz-built-world-biggest-museum-african-art-eg17-2727999/.

Lehmann Maupin. “Nicholas Hlobo.” Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.lehmannmaupin.com/artists/nicholas-hlobo.

Noe, Christoph. “How Jochen Zeitz Creates the World’s Largest Museum of Contemporary African Art.” Larry’s List. Accessed November 4, 2018. http://www.larryslist.com/artmarket/the-talks/how-jochen-zeitz-creates-the-worlds-largest-museum-of-contemporary-african-art/

Roux, Caroline. “Cape Crusader: meet Jochen Zeitz, the entrepreneur behind Africa’s largest museum of contemporary art.” The Telegraph, October 14, 2017. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/luxury/art/zeitzmocaa-cape-town-jochen-zeitz/.

Ruiz, Cristina. “Insize Zeitz Mocaa: our guide to Cape Town’s new mega-museum.” The Art Newspaper. September 15, 2017. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/zeitz-mocaa-our-guide-to-cape-towns-new-mega-museum.

Scher, Robin. “A Closer Look at Africa’s First Contemporary Art Museum.” Hyperallergic. September 22, 2017. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://hyperallergic.com/401607/a-closer-look-at-africas-first-contemporary-art-museum/.

Sieff, Gemma. “From Maize to Museum: The Long-Awaited Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa Aims to Let the Continent Tell Its Own Story.” ARTnews. September 7, 2017. Accessed November 4, 2018. http://www.artnews.com/2017/09/07/from-maize-to-museum-the-long-awaited-zeitz-museum-of-contemporary-art-africa-aims-to-let-the-continent-tell-its-own-story/

SMAC Gallery, “Cyrus Kabiru.” Accessed November 4, 2018. https://smacgallery.com/artist/cyrus-kabiru-2/.

Sulcas, Roslyn. “A Provocative Museum Places African Art on the Global Stage.” The New York Times. October 27, 2017. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/27/arts/design/zeitz-museum-contemporary-art-cape-town.html.

The B Team, “Jochen Zeitz: Co-Founder, The B Team.” Accessed November 4, 2018. http://www.bteam.org/team/jochen-zeitz/.

World Forum on Natural Capital. “Jochen Zeitz.” October 25, 2015. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://naturalcapitalforum.com/news/article/jochen-zeitz/.

Zeitz MOCAA. “Museum Educator - Schools, Youth and Family Programmes.” September 21, 2018. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://zeitzmocaa.museum/careers/museum-educator-schools-youth-and-family-programmes/.

Zeitz MOCAA. “Zeitz MOCAA: Mission Statement.” Accessed November 4, 2018. https://zeitzmocaa.museum/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Mission-statement.pdf.

Zeitz MOCAA. “Zeitz MOCAA Officially Opens as the World’s Largest Museum Dedicated to Contemporary Art From Africa and its Diaspora.” Zeitz MOCAA press release, September 15, 2017. Accessed November 4, 2018. Zeitz MOCAA website. https://zeitzmocaa.museum/zeitz-mocaa-officially-opens-worlds-largest-museum-dedicated-contemporary-art-africa-diaspora/

Zeitz MOCAA. “Zeitz MOCAA Unveils Its Opening Exhibitions.” Zeitz MOCAA press release, September 15, 2017. Accessed November 4, 2018. Zeitz MOCAA website. https://zeitzmocaa.museum/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/150917_Release_Zeitz-MOCAA-Inaugural-Exhibitions.pdf.

#jochen zeitz#zeitz#zeitz museum#jochenzeitz#contemporary african art#contemporaryafricanart#art#art blog#contemporary art#african contemporary art#contemporary art blog#cape town#cape town art#cape town arts#african art

1 note

·

View note

Text

An Introduction to Jean Pigozzi

“When I started, everyone thought that I was an idiot. But now many museums - like Pompidou, Tate, Metropolitan in New York, Los Angeles County Museum - they all want to do shows from my collection,” explains French-born Italian collector Jean Pigozzi in 2016, reacting to the rise in popularity and interest in Contemporary African art. At sixty-four years old, Pigozzi has amassed over 10,000 works of Contemporary African art with a particular focus on artists who live and work in sub-Saharan Africa. Pigozzi’s collection is different from other collections of Contemporary African art (such as the Zeitz collection) which include works by artists who may not be currently living and working in Africa and which feature artists from all different parts of the continent. What is not different, however, is Pigozzi’s desire to help African artists to share their stories with the world. Although his collection does not have a permanent museum or location where it can be shown altogether, the works are frequently on loan to prestigious museums internationally and featured in exhibitions worldwide.

Pigozzi was an artist before he ever became an art collector; he discovered photography at a young age as a way to capture the world around him and express himself without extensive writing, which he struggled with due to dyslexia. Growing up in what he calls a “typical European bourgeois” household, the young aficionado regularly attended art museums with his mother, and his parents even had a modest collection of Impressionist works. It was not until the 1970s, when he attended Harvard University in the United States, however, that Pigozzi exposed himself to art that was more avant-garde. Pigozzi recalls spending weekends in New York visiting MoMA, the Whitney, and galleries downtown. Pigozzi found the art around him fascinating: “It was all so exciting,” he said. “This was the time of Conceptual Art and Minimalism; Carl Andre and Sol LeWitt.” His first purchase was a small Sol LeWitt drawing. At age twenty one, Pigozzi inherited his father’s fortune and became wealthy enough to enjoy a life of leisure dedicated to following his passions - including his burgeoning interest in art - wherever they led him.

In 1989, Pigozzi discovered Contemporary African art when he attended the well-known, yet controversial, exhibition Magiciens de la terre at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris. The exhibition, which is seen as one of the major turning points for the art world’s globalization, featured works by more than 100 artists from 50 countries, half of which were so-called “non-Western.” Upon seeing the show, Pigozzi was struck by the creativity of the African artists whose works were featured. Pigozzi was not able to purchase the works in the show, which included those by now relatively more well-known Contemporary African artists Bodys Isek Kingelez and Chéri Samba, because they were owned by a French television station. However, Pigozzi was introduced to André Magnin, who helped curate the show, and he became Pigozzi’s advisor as he began to collect Contemporary African art. Most of the works that the collector has acquired were purchased directly from the artists themselves, and many of them were discovered by Magnin through his journeys into Africa scouting for artistic talent.

While Pigozzi himself has never been to Africa, he remains committed to meeting and talking with the artists whose work he collects, finding collectors who do not do so to be more vulnerable to the tall tales sometimes told by art world professionals when trying to make a sale. Among the 71 artists listed on Pigozzi’s collection website, only some of them have been featured in gallery or museum shows - lending itself well to the interpretation that Pigozzi enjoys discovering new artists. Pigozzi has been credited for essentially launching the careers of artists in his collection who do have more art world visibility. For instance, journalist Tess Thackara argues: “Without Pigozzi’s patronage, it’s easy to imagine that [Kingelez] would never have made it onto the MoMA’s walls; the high-profile collector has undeniably brought visibility to Kingelez’s work and played a crucial role in its preservation.”

When he talks about his motives for collecting the art that he does, Pigozzi never talks about financial viability, stability or even potential to produce any sort of profit. In fact, Pigozzi believes that anyone viewing his collection through a financial lens would see it as a “mistake,” with his most valuable paintings being worth $100,000 at maximum, according to the collector - a small amount of money compared to the millions of dollars that Warhol’s and Basquiat’s achieve at auction. But, Pigozzi does not view his works through a financial lens, explaining that while his choice of category may not make sense of a collector interested in making a long-term profit off his works, it makes sense for Pigozzi because he feels he occupies an interesting and unique niche within the art world.

Artworks from The Contemporary African Art Collection (CAAC), which is what Pigozzi calls his collection, have been featured in what one might argue to be every important exhibition of Contemporary African Art in major art institutions in 2018, including Romuald Hazoumè at Gagosian, Park & 75, New York; Platform: Barthélémy Toguo: The Beauty of Our Voice at the Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, New York; and Bodys Isek Kingelez: City of Dreams at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. All of those exhibitions have gotten major press coverage, including mentions or full articles in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, TIME, and Forbes.

In terms of his plans for the future, Pigozzi has expressed a desire to contain his collection within one place and make it available to the public without having to be dispersed among various museums. “It would be sad if 30 years of work disappeared, and the 10,000-strong collection was dispersed,” Pigozzi laments. Yet, Pigozzi realizes that he may not have the resources to put all of his art in one place right now - at least not in a place that he himself funds. “If I [were] Bill Gates,” he says, “I would build a museum. But I’m not Bill Gates. So, I’m open to suggestions,” Pigozzi discloses in an interview with an implied sense of humor. In the meantime, viewing sublime works from Pigozzi’s collection, like the imaginative Bodys Isek Kingelez’s utopian city sculptures at MoMA, is not a bad option for those of us interested in unveiling the stories that Pigozzi readily makes available to the art-viewing public.

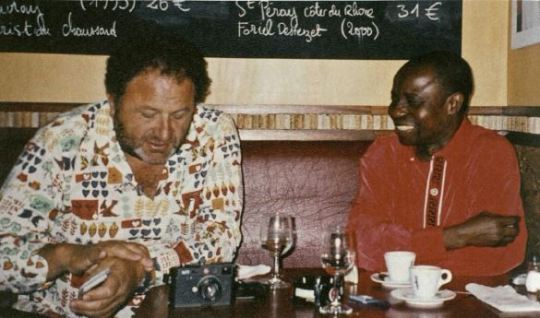

Jean Pigozzi and Chéri Samba, Paris, 2002. Source: Les Initiés: un choix d’oeuvres (1989-2009) dans la collection d’art contemporain africain de Jean Pigozzi, Fondation Louis Vuitton, 2017.

Photo at top: Jean Pigozzi. Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-Jy-ggtttZQ.

Bibliography:

Artforum. “Jean Pigozzi to Build Foundation for Contemporary African Art.” April 26, 2017. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.artforum.com/news/jean-pigozzi-to-build-foundation-for-contemporary-african-art-68078.

Baumgardner, Julie. “Inside the World’s Largest Collection of Contemporary African Art.” Artsy. October 12, 2015. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-inside-the-world-of-jean-pigozzi-the-tech.

Buffenstein, Alyssa. “Investor and Celeb Photographer Jean Pigozzi Is Searching for a Home for His African Art Collection.” artnet News. April 27, 2017. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/jean-pigozzi-foundation-contemporary-african-art-938897.

Caacart.com. “Artists.” Accessed November 4, 2018. http://caacart.com/caacart-artists.php. Caacart.com. “Exhibitions.” Accessed November 4, 2018. http://caacart.com/caacart-exhibitions.php.

Caacart.com. “Home.” Accessed November 4, 2018. http://caacart.com/.

Christie’s. “The Insider’s guide to Contemporary African art.” February 15, 2018. https://www.christies.com/features/The-insider-guide-to-Contemporary-African-art-8887-1.aspx.

Delson, Susan. “In the Hamptons, This Artist Builds the Boat And Serves the Coffee.” The Wall Street Journal. July 26, 2018. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.wsj.com/articles/in-the-hamptons-this-artist-builds-the-boat-and-serves-the-coffee-1532617982.

Edwards, Natasha. “Jean Pigozzi’s Massive Collection of African Art.” Surface. November 30, 2015. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.surfacemag.com/articles/20151130jean-pigozzis-massive-collection-of-african-art/.

Friedel, Julia. “Magiciens de la Terre.” Contemporary And. August 12, 2016. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.contemporaryand.com/magazines/magiciens-de-la-terre/.

Harris, Gareth. “Venture capitalist Jean Pigozzi plans foundation to house contemporary African art collection.” The Art Newspaper. April 26, 2017. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/venture-capitalist-jean-pigozzi-plans-foundation-to-house-huge-contemporary-african-art-collection

Meistere, Una. “Jean Pigozzi.” Independent Collectors. July 19, 2016. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://independent-collectors.com/collectors/jean-pigozzi-arterritory/.

Pigozzi, Jean. “Jean Pigozzi: The Collecting Life.” Caacart.com. June 2005. Accessed November 4, 2018. http://caacart.com/about_jp_en.php.

Press, Clayton. “Romauld Hazoumé, Gagosian, Park & 75, New York.” Forbes. September 23, 2018. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.forbes.com/sites/claytonpress/2018/09/23/romuald-hazoume-gagosian-park-75th-new-york/#5227dbdf3b58.

Schwendener, Martha, Will Heinrich, and Jillian Steinhauer. “What to See in New York Art Galleries This Week.” The New York Times. September 13, 2018. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/13/arts/design/what-to-see-in-new-york-art-galleries-this-week.html.

Shapiro, Eben. “At MoMA, a Genius Finally Gets His Due.” Time. June 28, 2018. Accessed November 4, 2018. http://time.com/5324720/body-isek-kingelez-moma/.

Smith, Roberta. “Fantastical Cityscapes of Cardboard and Glue at MoMA.” The New York Times. May 31, 2018. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/31/arts/design/bodys-isek-kingelez-review-moma.html.

Thackara, Tess. “Bodys Isek Kingelez, Maker of Utopian Cities, Finally Gets the Retrospective He Deserves.” Artsy. May 24, 2018. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-finally-notice-bodys-isek-kingelezs-utopian-vision.

#jean pigozzi#pigozzi#jeanpigozzi#contemporary african art#contemporary art#african art#african contemporary art#blog#art blog#art blogger#contemporary art blog#art collectors#art collector#collectors#art collector profile#art collecting#cheri samba

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Introduction to Chéri Samba

Known for his playful, brightly-colored, graphic paintings with a political message, Chéri Samba is one of the most visible Contemporary African artists on the market today. His goal, as expressed, is to make people think critically about the world around them, and his topics range from the impact of colonialism to what it means to be a successful artist. Samba’s work has been included in basically every turning-point exhibition that is considered part of the genre’s history. His paintings have also been featured - and highly publicized - in every single one of the Sotheby’s Modern & Contemporary African art sales since they began in 2017. He exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 2007, and is represented in the permanent collections of prestigious institutions like MoMA and the Centre Pompidou. Through this blog entry, I aim to introduce the reader to Samba and his unique paintings, providing context that will help hopefully encourage him or her to explore further.

Born in Kinto M’Vuila, a small village in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Samba came of age in a pivotal moment for his country. In the 1960s, the DRC was liberated from its Belgian colonial rule - known to be among the most violent and oppressive - and entered into a new era with “music, bars and cars” as it became an independent state. Eventually, the DRC’s economy crashed and became entangled in poverty, but the time in which Samba began to paint for a local audience (the 1970s) was one characterized by optimism and great political change. Through his artwork, Samba has set out to portray the everyday realities of Congolese life from the late 20th century up until the present day. Topics have included the involvement of youth in violence and corruption (ex. Little Kadogo, I am for Peace, That is Why I Like Weapons, 2004), as well as the prosperity of the upper-class (ex. Un Vie non Ratée (A Successful Life), 1995).

Samba has shown an interest in dilemmas that go beyond the borders of his home country and that affect us globally as well. The painting Probléme d’Eau (Water Problem), 2004 takes the international water crisis as its main theme, showing his intention to use his art to serve a purpose, or at the very least, make a political statement. Speaking about the difficulty accessing clean drinking water in Africa, Samba has said: “It’s a ridiculous problem. Why don’t the Americans help African governments to put a water tap in every home? It might be expensive, but I wonder, how much are they spending on missions to find out if there is water on Mars?” With this painting, Samba illustrates what he finds to be the absurdity of forgoing the needs of our own species in order to look for life (or evidence of life in the form of water) on other planets.

Chéri Samba, Probléme d’Eau, 2004. Acrylic on canvas. Source: http://art-for-the-world.blogspot.com/2016/05/world-water-joy-project-participating_48.html.

Samba’s personal life plays an important role as well in the understanding of his works because many of his later works, from the late 1980s onwards, take this topic as their main theme or focal point. Samba always knew he wanted to be an artist, even from when he was a young child drawing pictures in the sand in Kinto M’Vuila. In primary school, Samba was known as the best artist, and he even sold his drawings to friends. Worried that he might not be able to make enough money off his drawings, Samba turned to painting by the time that he got to secondary school in hopes that it would lead him to a real career. One of Samba’s paintings was taken on tour with the school’s soccer team and received a huge positive reaction. Looking at the painting, Samba realized he needed to get out of his small village and pursue his artistic talent seriously.

Samba’s father, however, was not supportive of his son’s talent for art. Instead, he wanted his eldest son to stay home in the village and take care of the family farm. Samba’s struggle with his father to feel support for his artistic career plays a major role in the artist’s personal history, and has served as the inspiration for some of Samba’s paintings. In Le pardon libére, 2015, we see flames burst from Samba’s heart, as he dreams of following his love for creating art. Samba’s father stands with his back facing his son, representative of his dismissiveness regarding his son’s dream. Knowing that Samba was one of ten children, and the oldest male child, we might have some sympathy with his father, who was paying money for his son to get an education in order to help his family’s business.

Chéri Samba, Le pardon libére, 2015. Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0loCX-b8hGQ.

At age sixteen, Samba decided that it was time to follow his heart, even without his father’s support, and left for Kinshasa in 1972. Carrying with him a burning appetite for success and recognition of his talents, Samba arrived in the city and used his existing skills to land a job in a sign painter’s studio where he produced billboards and advertisements for local clientele. Three years later, at age 19, Samba opened up his own sign painting studio and also began drawing cartoons for Congolese entertainment magazine called Bilenge Info. The same year, Samba experimented with painting on sacking cloth, canvas being too expensive, and showing his work on the street. At first, people would pass by and not really notice his artworks. To captivate the attention of the Kinois who passed by, Samba began using text in his paintings, incorporating speech bubbles and narrative lines usually written in French or Lingala (one of the four DRC languages).

His paintings became popular with an intentional audience when Samba participated in the exhibition Les Magiciens de la Terre in Paris in 1989. Following the show, collector Jean Pigozzi began acquiring works by the artists featured in the show, including Samba- whom has since achieved international fame within the Contemporary African art world. In 2004, the artist landed a solo show (J’aime Chéri Samba) at Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain in Paris, and was featured in another show there in 2015-2016 (Beauté Congo 1926-2015). Formal exhibition catalogues were produced for both shows, and although written in French (and therefore not accessible to everyone interested in researching the artist), they provide a valuable record of Samba and his work. The catalogue for Beauté Congo 1926-2015 is available in major art research libraries like the Watson Library at the Met and the MoMA library.

One of the most well-known (or at least visible in terms of the Contemporary African art market) Samba works is titled J’aime La Couleur (I Like Color), of which the artist made many versions. The artist himself is shown in the center of the composition, holding a paintbrush dripping with different colored droplets. The central figure is also slightly surrealist, as his skin is unfolding into a staircase-like form into the sky. Different versions of the work have come up at auction fifteen times. Perhaps the work is so popular because color is one of the signature marks of Samba’s paintings, and here he declares his love for color - matching his personal philosophy with his artistic style. Discussing the work, Samba explains: “Colour is everywhere. To me, colour is life. Our heads must twirl around as if in a spiral to realise that everything around us is nothing but colours. So I say 'I like colour' instead of saying 'I like painting'. Colour is the universe, the universe is life, painting is life."

Chéri Samba, J’aime La Couleur, 2005. Source: http://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2018/modern-contemporary-african-art-l18801/lot.82.html.

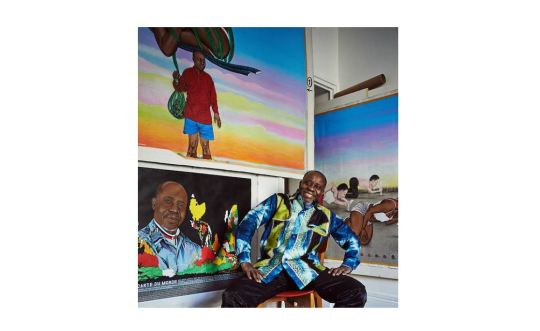

Chéri Samba in his studio, Kinshasa, 2003. Source: Les Initiés: un choix d’oeuvres (1989-2009) dans la collection d’art contemporain africain de Jean Pigozzi, Fondation Louis Vuitton, 2017.

My personal favorite Samba work is one in which he displays his signature whimsical, almost surrealist, tendency in full-force in order to relay his message. The work is called Le secret d’un petit poisson devenu grand (The secret of a small fish grown up), painted in 2002. The purpose of the painting is to instruct young artists on how to achieve success. Seeing himself as a role model, Samba has said that he hopes to inspire the next generation of African painters.

Chéri Samba, Le secret d’un petit poisson devenu grand (The secret of a small fish grown up), 2002, Oil on canvas, 81 x 100 cm. Source: http://www.pascalpolar.be/site/artisteview.php?nom_de_tri=Ch%E9ri%20Samba.

In the work, the little fish becomes big because he has a “secret,” and that is listening to everybody, but ultimately making his own decisions with his heart. For this reason, the anatomical heart fills the largest ear present on the man-fish figure, symbolizing that among all the voices that we hear, the one of our hearts is the most important. If no one is criticizing you, Samba explains, then it means that no one cares about you. In fact, this kind of exposure is even more important for African artists, Samba believes, because Africans should be proud of what they do. Before the exhibition Magicians de la Terre, Samba believes that people in the international art world did not believe that Africans could make art in a contemporary style.

Still working and making art, Samba splits his time between Kinshasa and Paris, and is represented by Galerie Pascal Polar in Brussels, Belgium. In terms of what Samba has been up to recently, his works were shown at The Fondation Louis Vuitton in 2017 as part of the exhibition Art/Afrique, le Nouvel Atelier, which featured works from the Pigozzi collection. Gallery Magnin-A, based in Paris, showed Samba’s work at 1-54 Contemporary African Art fair in London in 2017. Sotheby’s sold four of his paintings in their Modern & Contemporary African Art auction in May 2017, five in their March 2018 auction, and seven in their October 2018 auction. Concurrent to the inaugural edition of 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair in Marrakech, Samba’s work was shown in an exhibition at the Museum of African Contemporary Art Al Maaden (MACAAL) in February 2018. In the summer of 2018, his paintings were shown at the Evora Africa festival in Portugal and at the University of Michigan. Who knows what’s next on the horizon for this Contemporary African art star? We can only stay tuned into ContemporaryAfricanArtUnframed.tumblr.com to find out.

Photo at top: Chéri Samba, Paris, France, March 13, 2013 in his Paris workshop. © Antoine Doyen. Source: https://antoinedoyen.photoshelter.com/image/I0000ikhRfWbsesE

Bibliography:

Abramowitz, Eden. “Chéri Samba and Congolese Popular Painting.” Sotheby’s. September 1, 2017. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.sothebys.com/en/articles/cheri-samba-and-congolese-popular-painting.

Art for The World. “World Water Joy: A Work in Progress- Participating Artist - Chéri Samba.” May 26, 2016. Accessed November 4, 2018. http://art-for-the world.blogspot.com/2016/05/world-water-joy-project-participating_48.html.

Artnet. “Chéri Samba, I Like Color - search results.” Accessed November 8, 2018. http://www.artnet.com/pdb/faadsearch/FAADResults3.aspx?Page=1&ArtType=FineArt.

ArtReview. “Chéri Samba- Congo’s Hogarth.” June 2007. Accessed November 4, 2018. http://www.fredrobarts.com/articles.html.

Bonhams. “Lot 19: Chéri Samba: J’aime la couleur.” Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.bonhams.com/auctions/23091/lot/19/.

“Chéri Samba.” In Luminós/City.Ordinary Joy, Ethelbert Cooper Gallery of African & African American Art. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014. Exhibition catalogue.

Crichton-Miller, Emma. “Congolese art at Fondation Cartier.” Financial Times. August 7, 2015. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.ft.com/content/d7bf402e-3a92-11e5-bbd1-b37bc06f590c.

Culture Trip. “Chéri Samba: The Art of Telling the Truth.” January 29, 2016. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://theculturetrip.com/africa/dr-congo/articles/cheri-samba-the- art-of-telling-the-truth/.

Da Silva, José. “‘Global’ contemporary African art comes to rural Portugal - despite growing visa issues for artists travelling to Europe.” The Art Newspaper. May 30, 2018. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/new-festival-evora-africa-brings-global-contemporary-african-art-to-rural-portugal.

Ellis-Petersen, Hannah. “Paris hosts first ever retrospective of art from Democratic Republic of the Congo.” The Guardian. July 10, 2015. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/jul/10/democratic-republic-of-the-congo-art-paris-fondation-cartier.

Fondation Louis Vuitton. “Sweet Samba.” Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.fondationlouisvuitton.fr/fr/collection/artists/cheri-samba.html.

Galerie Pascal Polar. “Chéri Samba.” Accessed November 4, 2018.http://www.pascalpolar.be/Polaruserfiles/file/about/polar/samba/Cheri-SAMBA%20BIO.pdf.

Hawkins, Sydney. “U-M exhibition challenges traditional understanding of African arts and cultures.” University of Michigan News. August 8, 2018. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://news.umich.edu/u-m-exhibition-challenges-traditional-understanding-of-african-arts-and-cultures/.

LVMH. “‘Art/Afrique, le Nouvel Atelier’ at Fondation Louis Vuitton showcases African art.” April 26, 2017. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.lvmh.com/news-documents/news/artafrique-le-nouvel-atelier-at-fondation-louis-vuitton-showcases-african-art/.

Magnin-A. “Chéri Samba.” Accessed November 4, 2018. http://www.magnin-a.com/en/artistes/presentation/864/cheri-samba.

Magnin, André, Fondation Cartier. Beauté Congo: 1926-2015. Paris: Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, 2015.

Ochieng, Akinyi. “5 Works of Art You Need to See at 1:54 Contemporary African Fair London 2017.” OkayAfrica. October 6, 2017. Accessed November 4, 2018. http://www.okayafrica.com/5-works-art-need-to-see-1-54-contemporary-african-fair-london-2017/.

Orosz, Peter. “Kicking it with the cool kids of 1950s Kinshasa.” Jalopnik. November 29, 2011. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://jalopnik.com/5863413/kicking-it-with-the-cool-kids-of-1950s-kinshasa.

Piasa. “The contemporary art of Chéri Samba.” April 18, 2018. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.piasa.fr/en/news/actualite-art-contemporain-cheri-samba.

Sesay, Nadia. “1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair Landing in Marrakech is 2018’s Most Anticipated Art Event.” OkayAfrica. February 23, 2018. Accessed November 4, 2018. http://www.okayafrica.com/1-54-contemporary-african-art-fair-lands-in-marrakech/.

Sotheby’s. “Chéri Samba: Une Vie non Ratée (A Successful Life).” Accessed November 4, 2018. http://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2017/modern-contemporary-african-l17801/lot.2.html.

Sotheby’s. “Results for ‘chéri samba.’” Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.sothebys.com/en/searchresults.html?query=cheri%20samba&refinementList%5Bdepartments%5D%5B0%5D=African%20Modern%20%26%20Contemporary%20Art.

We Are Our Choices. “CHÉRI SAMBA 1/3 - Congo Imagination.” YouTube Video, 8:01. May 10, 2017. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?list=PLiFbXVhb3POVGoJ6OD1ZitKuBO97947eP&v0loCX-b8hGQ.

We Are Our Choices. “CHÉRI SAMBA 3/3 - From Africa to the World.” YouTube Video. 7:25, May 17, 2017. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YQrwhAcJEMg.

Worldcat.org. “Beauté Congo: 1926-2015.” Accessed November 4, 2018. http://www.worldcat.org/title/beaute-congo-1926-2015-congokitoko/oclc/914160532&referer=brief_results.

#chéri samba#cheri samba#cherisamba#samba#contemporary african art#contemporary art#contemporaryafricanart#african art#african#democratic republic of the congo

1 note

·

View note

Text

What is Contemporary African Art?

Contemporary African art, according to the scholars who study it, is generally considered to be art created in the postcolonial time-frame, meaning the 1950s and beyond, by artists who are in some way connected to the African continent.

Debate arises over this definition, like all definitions, because of its scope - both in terms of time period as well as subject matter. For example, who can be considered to be an African artist? Do artists of African descent living in other countries count? Another question we might ask is: Why do we consider decolonization to be the mark of modernity, or the beginning of “contemporary,” and what do we do with the fact that different countries in Africa were ruled by different colonizers, who left at different times? With a continent composed of 54 nations, we might wonder how we could - or whether we even should - attempt to cover so much ground with one definition for Contemporary African art.

To this point, many people - curators, art historians, and scholars - go to great lengths to avoid giving a specific and narrowly-defined definition for Contemporary African art. In their book Contemporary African Art Since 1980 (2009) renowned experts Okwui Enwezor and Chika Okeke-Agulu spend pages explaining the malleability of every single one of the points upon which they define Contemporary African Art. For instance, they say that today’s Africa “is not a flat field, but a series of shifting grounds composed of fragments, of composite identities, and micro narratives.” By the time one is done reading their introduction chapters, one honestly still might have no idea how to explain what Contemporary African art is in one sentence. In fact, it took me weeks, and plenty of books on the topic, to come up with the definition that I gave in my opening paragraph.

Although academics like Okwui Enwezor and Chika Okeke-Agulu, as well as others like Zoe Whitley, curator of international art at Tate Modern, are able to skirt giving a concise definition of Contemporary African art, market players and leaders (such as gallerists and auction house representatives) often must define the category for the purpose of marketing their sales and targeting specific consignors and collectors. Hannah O’Leary, Director and Head of Modern and Contemporary African art at Sotheby’s, explains that she defines Contemporary African art - at least in terms of which artists get to be included - as work created by those who are either from Africa, have lived in Africa, or have worked in Africa (implying that Africa has then had some influence on their work).

In terms of time period, most sources - academic and even colloquial (Wikipedia, Artsy, etc.) - agree that Contemporary African art is, in the words of scholar Sidney Littlefield Kasfir, “quintessentially postcolonial.” The majority of African countries that were colonized gained their independence between the 1950s to the 1970s - the period of time that also marks the beginning of Contemporary art in Western art history, although for different reasons. Kasifr explains, “While this is the same time-frame used to describe Western ‘contemporary’ art, the reasons for the importance of the mid-1950s to mid-1960s as a watershed decade are different - this was when political independence was gained, when colonialism was cast off and when the enormous intellectual and creative euphoria which this engendered emerged.” Therefore, while Contemporary African art can be seen as beginning around the same time as Western Contemporary art, each is a symptom of its own cultural and art history. Instead of being spurred by avant-garde artistic movements like Abstract Expressionism, the contemporary in African art is considered to be a result of the freedom gained with the exit of foreign leadership in the middle of the twentieth century.

Contemporary African art must also be contextualized within Africa’s rich art history, including a tradition of art-making that spans back thousands of centuries, way before colonizers even began arriving in the late 1800s. For some, calling it “postcolonial” simply does not do the category justice, as it implies too much of a sense of before-and-after, meaning that all art before colonialism can be grouped into one category, and all art after colonialism can be grouped into one category as well. As people thinking about Contemporary African art, it would serve us well to remember that this pre-colonial/post-colonial dichotomy might be short-sighted.

On another note, we must not forget that “contemporary” as a term remains deeply tied to the present moment. No matter when it starts, it is never finished. The category might become too wide and too encompassing for future generations, or even for our generation as we continue to introduce African talent to the global art market. The idea of what exactly is meant by Contemporary African art is constantly open to change and will evolve with time, as well as with scholarship on the topic.

For the purpose of this blog, I will focus on the people who are making a living definition of Contemporary African art. I look at artists who connect themselves to the African continent - either through their heritage or their artistic practice, or both. I look at auction house sales, galleries and fairs that consider themselves to be part of “Contemporary African art.” Most importantly, I look beyond categorical nomenclature and dive deep into the passion and dedication of the people who create, promote, study and collect visual art connected to the African continent. It is through these stories that some Western audiences can begin to see African narratives unfold. In the words of Moroccan-born Founding Director of the internationally-renowned 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair, Touria El-Glaoui, “It is really through art that [Africans] can regain [their] sense of agency and empowerment. It is through art that [Africans] can really tell [their] own story.”

Bibliography:

Artsy. “Contemporary African Art.” Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.artsy.net/gene/contemporary-african-art.

Burns, Charlotte. “Transcript: Contemporary African Art.” Art Agency, Partners. October 5, 2017. Accessed November 4, 2018. http://www.artagencypartners.com/episode-16-transcript-contemporary-african-art/.

El Glaoui, Touria. “Inside Africa’s thriving art scene,” filmed August 2017 at TEDGlobal 2017, TED video, 7:58, Accessed November 4, 2018, https://www.ted.com/talks/touria_el_glaoui_inside_africa_s_thriving_art_scene/up-next.

Enwezor, Okwui and Chika Okeke-Agulu. Contemporary African Art Since 1980. Bologna: Damiani, 2009.

Kasfir, Sidney Littlefield. Contemporary African Art. London: Thames & Hudson, 1999.

Wikipedia. “Contemporary African art.” Accessed November 4, 2018. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Contemporary_African_art#cite_ref-:0_16-0.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Introduction

Welcome to my blog on Contemporary African art. My name is Deanna, and I started this blog in November 2018 to share the stories and artwork of the incredible talent that comes from the African continent and African diaspora. The blog is a collection of essays that focus on the Contemporary African artists and market players that one might encounter at auction or at art fairs right now.

Contemporary African art has been gaining visibility in the international art world more than ever before, especially in the last few years. In 2016, Sotheby’s launched its department for Contemporary African art and held its inaugural sale in that category in 2017. In 2013, Touria El Glaoui founded 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair, an art fair held now in London, New York and Morocco dedicated solely to showing work from artists connected to the African continent. In 2015, the Brooklyn Museum in New York presented the work of Contemporary African photographer Zanele Muholi, whose photographs aim to create visibility for the black lesbian and transgender communities of South Africa. The Zeitz MOCAA (Museum of Contemporary Art Africa), the largest museum dedicated to art from Africa and its diaspora opened in Cape Town in 2017, covering more than 65,000 square feet of gallery space with works by up-and-coming Contemporary African artists like Cyrus Kabiru and Nicholas Hlobo. Over 1,000 people traveled two hours outside of New York City in 2015 for the opening of an El Anatsui show at Jack Shainman Gallery’s upstate location. Clearly the market is teeming with untapped potential and hotter than it has ever been.

My interest in Contemporary African art was sparked last fall when I was working on a project for my graduate program where we were asked to come up with a business plan to start a branch of Christie’s (with a full saleroom) somewhere in Africa. I started looking at Contemporary African artists because I thought they might be a great way to get the business invested in something that could help connect it to its new location. I yearned for a good entryway into the category of Contemporary African art - a way to learn who is who, and understand some of the themes and issues tackled in the artwork that I was seeing. I couldn’t find anything like this blog, which would have given me a great place to start for my research. Instead, I read everything I could on Contemporary African art that I pulled up on Google, and slowly compiled information and gained a sense of a market on my own over the course of the last year. My vision is that people like me can use this blog to help guide them as they explore this category and the incredible beauty produced by artists of African descent.

I hope to inspire my readers to learn more about the artists & people that I write about, as well as those that I have not yet written about, and to contribute their own perspectives to the conversation. I will be actively seeking guest writers starting this summer to submit articles that can help me cover more artists and people, and turn this blog into one that expresses a multitude of voices.

Bibliography:

Kinsella, Eileen. “Sotheby’s to Hold Its First-Ever Contemporary African Art Sale.” artnet News. April 26, 2017. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://news.artnet.com/market/sothebys-african-art-sale-938408.

Neilson, Laura. “At Jack Shainman’s Upstate Space, a Venice Golden Lion Winner Has Room to Spread Out.” T Magazine – The New York Times. May 18, 2015. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://tmagazine.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/05/18/jack-shainman-el-anatsui/.

Sotheby’s. “African Modern & Contemporary Art.” Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.sothebys.com/en/departments/african-modern-contemporary-art.

Sotheby’s. “Auction Results – Modern & Contemporary African Art, 16 October 2018.” Accessed November 4, 2018. http://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/2018/modern-contemporary-african-art-l18802.html.

Sotheby’s. “Meet Hannah O’Leary - Champion of Contemporary Africa Art.” February 1, 2017. Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.sothebys.com/en/articles/meet-hannah-oleary-champion-of-contemporary-african-art.

The Brooklyn Museum. “Zanele Muholi: Isibonelo/Evidence – May 1-November 8, 2015.” Accessed November 4, 2018. https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/exhibitions/zanele_muholi/.

Zeitz MOCAA. “Zeitz MOCAA Officially Opens as the World’s Largest Museum Dedicated to Contemporary Art From Africa and its Diaspora.” Zeitz MOCAA press release, September 15, 2017. Accessed November 4, 2018. Zeitz MOCAA website. https://zeitzmocaa.museum/zeitz-mocaa-officially-opens-worlds-largest-museum-dedicated-contemporary-art-africa-diaspora/

Zeitz MOCAA. “Zeitz MOCAA Unveils Its Opening Exhibitions.” Zeitz MOCAA press release, September 15. Accessed November 4, 2018. Zeitz MOCAA website. https://zeitzmocaa.museum/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/150917_Release_Zeitz-MOCAA-Inaugural-Exhibitions.pdf.

1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair. “About 1-54.” Accessed November 4, 2018. http://1-54.com/about/.

#introduction#contemporary african art#art#african art#contemporary art#art blog#contemporary art blog#african contemporary art

1 note

·

View note