I dabble with music and the creation of pretty things – but even that is debatable

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

06202021

Saturday, 6 Feb 2021, 21:35:05-22:09:40

Singapore, Singapore

Warm, fair

Calm, a little tired

I’ve been feeling a little guilty for neglecting this and certain other goals or scheduled activities I’ve set for myself. Since my return to Singapore last weekend, I’ve spent a fair amount of time inside my own head, and sometimes deliberately keeping it empty. I’ve been blessed to be able to indulge myself a little, and have avoided the boredom from being cooped up during this “Stay Home Notice” period.

I’m still a little jet-lagged, and it feels like my person has started to settle into seeking and finding comfort in slowness. I am reminded of my sometimes fiery nature and it makes me wonder where that arises when it does – it seems strange that it comes and goes like lightning.

I recently submitted my university application, and think about it intermittently. I try not to think about it, and try to focus instead on next steps... I’m still not certain what they might be.

This period of isolation has been kind to me, and I wonder if this is how others have taken to it too. It has been quite luxurious if I dare say so. I have spent the days talking to James in the morning and at night during his commutes to work, and the rest of the hours reading and taking photographs from the balcony of the room, or taking baths with the bubble bombs sent by Sam. My mother and uncle have been sending me food and snacks religiously with or without me asking, too. It is so lovely to feel so loved.

A part of me misses the life I started to build for myself in New York, but mostly I think about how to build my world here all over again. I’m nervous about the opportunities I might be able to craft for myself, and about the relationships I have long neglected here. I miss James a lot, and I want to create something for him to come here for. Regardless of the affirmation and encouragement I receive from friends and family, there is always a quiet anxiety that sits within me, a soft voice that speaks to me about catastrophe and failure. I think that voice can be helpful, but for now, I’m trying to lower the volume and pretend it isn’t right.

Gratitude list for right now:

Resources: my computer, camera, and books that have kept me occupied, my friends, family, and my partner who have called to check up on me and who keep me in their thoughts despite my physical absence

Reminders that my past life and that the one I am constructing right now are not disjointed

The bittersweetness of going away and coming to all happening at once

Flexibility with myself

0 notes

Text

20210107

Monday, 7 Jan 2021, 21:38:50- 21:52:15

Staten Island, New York

Cold, windy

Stressed out and busy, feeling slightly like I’m a wheel not well oiled

It’s strange preparing for an extended leave for so long. From the time the seed of escapism is sown, until the blossoming of thought to action to completion, and it being replaced by a new urgent plan somehow or another related to the previous one.

Gratitude list for this week so far:

The gratification of drawing or doodling

I’m getting better at it but I haven’t tried to use this part of myself in awhile. Anyway, it’s nice to be able to build things from lines and make something fun looking. I like that it’s non-committal in that it doesn’t need to get finished, but it looks better the further you carry it. Sometimes not! Some of them want to be silly and so they just are. (Listen more to things around you and what they want to be)

Scary but I guess it really could be more thought of as exciting: Setting up my life back home again

Choices: It’s nice that I’ve found a way to buy myself time without drying myself out

Note: Having a single plan and idea that doesn’t account for contingencies or multiple plans occurring at the same time or none of them at all has never done you good. It’s good to be able to identify that and avoid it

I’m proud that I was able to, with time, reconcile the things about planning these possible futures that didn’t sit well with me

Opportunities and a flexible perspective to see how I might fit within it or adjacent to it

Things to write about in an effort to train my writing (glad to be able to invent opportunities for myself)

0 notes

Text

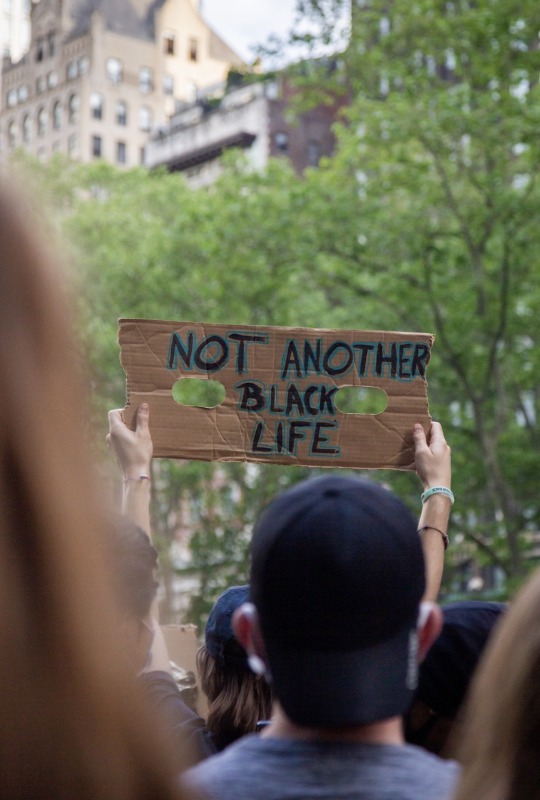

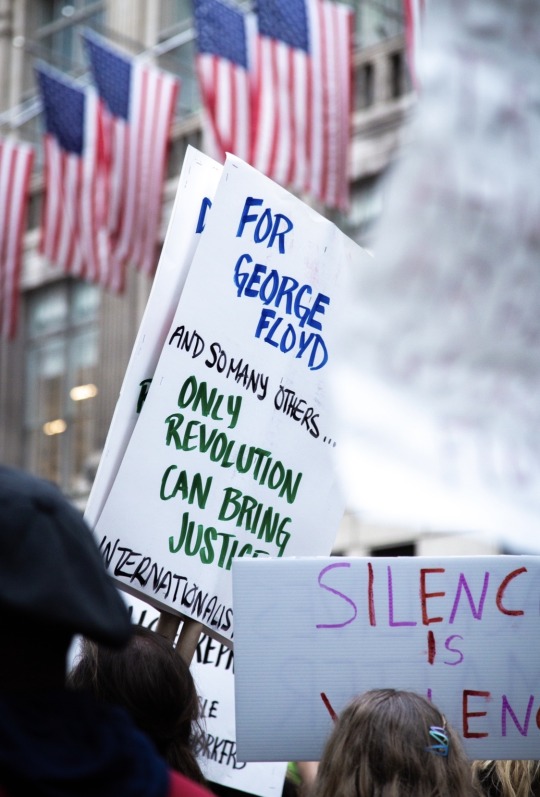

02062020 Bryant Park to Trump Tower, Manhattan, New York

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

0619: Graduation, Syracuse, NY

Sony RX10

0 notes

Photo

0419: Nicolai, Syracuse, NY

Sony RX10

0 notes

Text

Renaissance Italian Architecture: Roofs

The roofs of Renaissance Italian style of construction and design varied according to the building’s typology. In cases such as the Duomo of Florence, Santa Maria del Fiore, the domed roof was celebrated for its engineering prowess and beauty, and emphasised to accentuate the scale and grandeur of the building itself. This dome had a diameter slightly larger than the Pantheon and double the height (Mainstone, 2009). Compounding this, the dome was octagonal in plan and was constructed without supporting centering – an unprecedented feat at the time (Mainstone, 2009). This self-supporting domed roof was the pride of Florence, and it’s achievement showed Florence as a progressive city of influence, wealth, and learnedness.

Having a roof of such grandeur came with its own difficulties, and when proposing the construction of the dome, Brunelleschi devised an innovative construction method of containing a true circular dome within the thickness of the octagonal dome, and also by using a herringbone arrangement of brick-laying. This allowed the dome to be self-supporting and also cut costs of construction by eliminating the need for timber for the supporting centering (Mainstone, 2009).

While buildings of public interest such as the Duomo have highly celebrated roofs, in other buildings such as residential palazzi typology, roofs were typically downplayed to highlight the form of the building instead. In palazzo such as the Medici palace, classical cornices with large overhangs supported by brackets and embellished with designs ranging from dentils to egg and dart mouldings. In this case, the cornice was used to obscure or hide the actual roof, which was seen as purely functional and serving nothing to the ornamentation of the building. Palazzo Medici was a forereunner to the normalacy of the palace type during its time, and its overhanging cornice was the first of its kind. This is also seen in Palazzo Strozzi, where the completion of the cornice was prioritised on the front façade, which stands at the only fully completed face of the building.

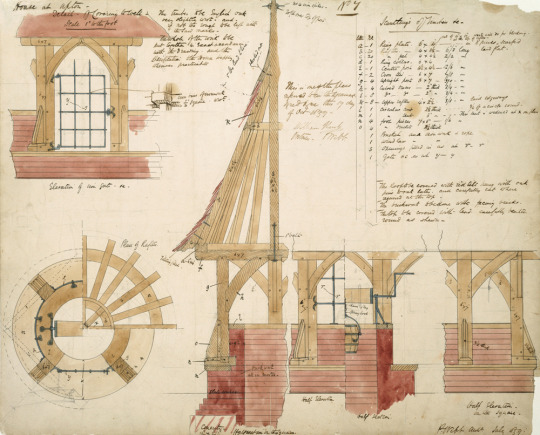

The roofs of these palazzo types were likely constructed with a capriata wooden truss system designed to support the ornate ceilings of the palazzo, transferring the load of the roof onto the load bearing walls. While the ceilings were heavy, the roofs themselves were typically simple terracotta tiling, and without much surface area as they were often flattened to have a very low pitch. Thus, the simple wooden beams of the capriata truss system was adequate in supporting these roofs in addition to being fairly easy to construct.

Primarily, Italian renaissance roofs that were not domes were very flat – justified by climatic reasons that compound the ability for a more downplayed roof to give importance to the main form of the building. Therefore, the roof was typically seen as a functional element rather than an ornamental one unless it was in a celebrated religious building. Despite being the precursor for much of European style, Italian renaissance style was not copied in its entirety elsewhere. On the contrary, the Mansard roofs characteristic of France are viewed as a primary element in a building. The steeply sloping roofs serve both practical and aesthetic functions, allowing snow to slide off the roof during winter while not compromising useful square footage, and being a characteristic unique to French style buildings. In Chateau de Chambord, the Mansard roofs are modified to create an animated roofscape that complement the rest of the building’s exciting design, with the primary purpose being to showcase the patron’s decadence, power, and wealth (Tanaka, 1992).

0 notes

Text

‘Yayoi Kusama: Life is the Heart of a Rainbow’ Review: visual spectacle with a missed opportunity

Singapore

The Kusama exhibition opened at the Singapore National Gallery just over a month ago and has been making waves on all platforms of social media. In recent years, the reclusive 90-year-old Japanese artist has grown to become everyone’s favourite, inheriting her role as The Avant-Garde Artist and Provocateur from the likes of Salvador Dali and Andy Warhol.

I made several attempts to view the exhibition before finally succeeding to beat the crowd by visiting the museum at 10am on a Tuesday. Otherwise, the queues were monstrous, and the daily ticket quota meant that if you arrived late you might not be allowed entry (upon first hearing this, I thought “great, the galleries shouldn’t be that crowded, they’re making effort to do a reasonable job with traffic control so that people can actually look at what is being put on display”, but I was so very wrong).

Walking through the gallery, you are constantly surrounded by people babbling away, or children running around with their parents telling them to behave, each and every one of these visitors stopping for a few extra seconds to get that perfect selfie or Instagram pic. Strange, nobody is really stopping to look. It doesn’t really help that in the timed displays, each viewing only lasts about 20 seconds.

I recall distinctly how during my visit to this exhibition I heard someone say “oh, yeah, she’s the dot painter”. A woman who has challenged so many limitations of the art world, and played a key role in the development of Surrealist and Pop Art. Ultimately, she can only be “the dot painter”.

The exhibition display spans most of the third floor of the National Gallery of Singapore, and begins with a few early small scale Surrealist styled works that Kusama did in a traditional Japanese style of painting, progressing into a series of Infinity Net paintings. Among these Infinity Net paintings are two sculptures, Death of a Nerve (1976) and Statue of Venus Obliterated by Infinity Nets no. 2 (1998), leading to three of her well-known pumpkin-themed works (two paintings and one installation) that conclude the first gallery’s display. In the adjoining hallway between galleries 1 & 2, a series of mosaic tiled pumpkins are scattered about with some free reading material placed in the corner for passers-by.

Entering the next gallery, visitors are first briefed on the long waiting times for some of the displays, and not to touch the work, before being greeted by a maze of convex mirrors that comprise the Invisible Life (2000) installation. This labyrinth ushers us into the display in gallery 2 that mostly surrounds Kusama’s soft sculptures and her time in New York City, save for the Infinity Mirrored Room: Gleaming Lights of the Souls (2008). Among the soft sculpture works is an almost random hanging of Kusama’s Cage, Painting, Women (1967 - 1970), three mixed media paintings that feature depictions of Elizabeth Taylor, Mata Hari, and Marilyn Monroe, who Kusama has referred to as “bad girls”. Her work that tackles her time in New York City and her activism is tucked away in a corner of this gallery, labeled as a restricted section for persons aged 18 and above due to “mature content including nudity and sexual content” despite the narrative of her soft sculptures being directly associated with said sexual content. Never mind that some of her soft sculptures are almost explicit visual references to genitalia (did anybody see the glowing red sculpture mounted on a canvas whose form basically resembled the female genitals? I most certainly didn’t.) This gallery finishes off with a video display of Kusama singing a song about her dealings with depression and prescription drugs.

The third gallery space starts with Love Forever (2004 - 2007), a series of 50 uniformly-sized black and white canvases drawn in felt marker, stacked around each other in a grid and covering almost all the walls in the room. In the middle of the room is another mirrored box titled I Want to Love on the Festival Night (2017), a dazzling display reminiscent of the iridescent glow of fun fair lights. The next room is fun and bright with playful polka dots and giant tulip sculptures that comprise With All My Love for the Tulips, I Pray Forever (2013), leading into the final room of gallery 3 that displays the My Eternal Soul series (2009 - present) with some of her colourful amoebic sculptures. Finally, the show concludes with Narcissus Garden (2017) that has been installed in the City Hall Chamber, an installation that was first realised at the Venice Biennale in 1966 and has been repeated for various different sites over the years.

While the exhibition is wonderful because of Kusama’s art, I felt that it lacked the ability to translate her story to the visitors. This exhibition is full of fun and folly and is undoubtedly enjoyable, save for the crowds and queues for brief viewings of some of the mirrored installations. And although I hate to sound sour, perhaps the curators and organisers overlooked their public responsibility for the sake of increasing profit and ticket sales. The problem with most contemporary art and how they are perceived by the public is that there is often a lack of context for us to read the work from. And although Kusama’s work is relatable and lovable because of its beauty and vibrancy, this exhibition failed to provide ample context for us to understand it, and thus the exhibition falls short of being great.

Perhaps the greatest irony of this exhibit is that the visitors are largely interested in getting selfies in front of pretty backgrounds for Instagram, but when you really look at her work, Kusama has explored so many ways of diminishing the importance of the Self in favour of the Whole. When I attended the panel discussion on this exhibition that was held by the National Gallery, the curators spoke extensively on the idea of “obliteration” and the significance of that idea to the work of Yayoi Kusama. They spoke in lofty words of how the exhibition was about the Object and the Self, but not once did I think about how I stood relative to the display during my walk through the gallery. The curators mentioned the “obliteration of the ego”, but not once did I look around me and see anything more than people feeding and enhancing their egos. They spoke of the comfort of the image juxtaposed with the difficulty of the subject matter, but walking through the exhibition, I hardly felt uneasy about the subject matter that was presented to me - and I think I speak for almost all the attendees - because even though I was aware of Kusama’s struggles, it was not explained to me by this exhibition. Her work was presented as a series of highly photogenic pictures, perfect for racking up likes on the ‘gram, but save for tiny labels to certain works that were usually tucked away and presented almost separately from the works they were addressing, there was very little that was done to address the “difficult subject matter” that these curators claimed to be presenting. Kusama’s abstract and surrealist works succeed in themselves, but for most of us they remain ambiguous and firmly grounded in the world of abstract and difficult to unpack.

My greatest frustration with this exhibition has been experienced outside the walls of the gallery. Almost daily, I come across at least one photoset on Instagram or one Facebook post on my newsfeed waxing lyrical about how incredible this exhibition was and how “I wish I was weird like Kusama”. No, you do not wish you were “weird like Kusama”. Yayoi Kusama’s unprecedented success coupled with her personal struggles as a woman in a male-dominated market, as well as her mental illness and esotericism (and I am sure I’m missing plenty of other hurdles she has faced in her career), are perfect reasons to relate this exhibition to something outside of this bubble of the “art world”. Particularly now, with taboos surrounding mental illness chipping away, and feminism being such a hot topic, this display of work by Kusama missed a huge opportunity to bridge a gap of understanding, and make the esoteric understood.

And so is this exhibition a worthwhile visit? Perhaps. But among all the Instagramming and snapchatting et cetera, don’t forget to save a few moments to obliterate your ego and look at what Yayoi Kusama has to offer.

#Yayoi Kusama#National Gallery Singapore#Life is the Heart of a Rainbow#exhibition#review#Singapore#clarissajane

0 notes

Video

vimeo

Alexandra & Ainsworth Estate, London, England (2017)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brutalism & Late Modernism

youtube

The Royal Festival Hall is a project that displays a full manifestation of modernism’s interests in publicness and privacy. Challenging existing archetypes of auditoriums and community buildings, this project uses an egg-in-a-box method of encasing the primary program (auditorium) in a publicly used building of multiplicity functions. Interestingly, the building was privatised in the 1980s, but still functions as a largely public-use building.

This structure and its counterparts along the southbank are all examples of architectural choreography that we have explored previously, beginning with the initial introduction to the idea of the picturesque. Down to its bespoke furnishings, the Royal Festival Hall is a building that promotes specific usage and activity in nuanced methods of choreography, and displays various degrees of gray zones and in-betweens that are much more “radical” than any preceding project.

Today, we see how this type of building with multifaceted types of (“plug-in”) programs have influenced the way we design for large scale projects to be inclusive of various audiences and types of public.

0 notes

Text

WWII & the Blitz

From 7 September 1940 to 6 June 1941, the Blitz ravaged the city of London as part of an indiscriminate war of industry and development, destroying 1 million homes and killing 40, 000 civilians. The “frontline” of war was redefined during this time period, where previously it was far-removed from urban life, it now was affecting domestic and urban life on the “home front” and thus a war effort that involved all demographics, regardless of gender, occupation, or descent.

Coventry after the air raid of 14 November 1940, BBC.

The bombings that ravaged the city of London resulted in drastic changes to the city landscape, and additionally saw a radicalisation of ideas that had been explored previously with early modernism and the émigré architects. As the shelling demolished whole districts and parts of buildings alike, this new cityscape proposed different understandings of interiority and exteriority (for example, exposing the interior of the house to the street without the use of a threshold such as walls or fenestrations as a type of “buffer zone”). Furthermore, as the disruption to everyday life affected people’s methods of dwelling, city infrastructure became repurposed and thus perceived differently, ultimately resulting in a changed perception of domesticity and public life.

Surviving the Blitz, BBC.

Inhabiting public infrastructure, the British.

This tragedy of war was in fact a type of unexpected and uncontrolled radicalisation of modernist concepts that had been explored in the preceding decades (primarily by émigré architects), and in effect was a type of forced “experiment” surrounding human life and pre-established normalcy of domesticity. And so with some of the reactions to war that were carried out in the city of London - such as the inhabitation of unconventional spaces such as tube stations -, what was brought about by method of destruction of war were physical and real manifestation of Modernist interests, grounding these previously niche intellectual interests in a tangible reality that was experienced by all.

Living in London and experiencing first hand how public infrastructure is so integral to the functions of the city, this multivalence of function comes off as something so natural, and makes me question the initial resistance to modernism and its efforts that were faced in the preceding decades. Although in a normal setting of city life absent from war, the inhabitation of public infrastructure seems so surreal and inconceivable, considering the situation also allows me to understand the “readiness” with which people carried out such activities during the time. Particularly when traversing the city and these tube stations, the plausibility of this reality becomes even more easily understood as the extensiveness of these stations and the underground network becomes realised. This was was an issue of social and material experience (particularly relative to established ideas of urbanity) that established new material relationships between people and objects (infrastructure), and removed familiarity to redefine relationships between human beings and living in the built environment.

Particularly when considering the projects and efforts in urban planning that emerged as a response to these phenomena, one begs the question: why was modernism so late to arrive in Britain? Why did modernism only “reach” Britain as a fully established style in the 1950s, when the same movement began it decline in continental Europe?

When modernism arrived in the form of émigré architects in the 1930s, efforts were largely not well received and had to tread lightly, avoiding anything that was obscenely radical. However, the Blitz worked as a type of catalyst, forcing radicalisation of these modernist concepts into a tangible reality in a situation where the public had no choice in accepting or denying it.

The curious thing however, is that following WWII and the Blitz, projects fully embraced these modernist concepts that they had been so quick to denounce in the most recent decade, and in some cases these were radicalised and explored in a much more extreme manner than any early modernist endeavour. Perhaps this was a result of a trickle effect from the limitations and restrictions (in livelihood and resource allocation) brought about by the war, but perhaps there was another more localised trigger for this that affected the perception of modernism in Britain.

Considering the recent political climate, and the apparently nationalistic interest of a British Britain, perhaps these sentiments have prevailed thorough the decades and are emerging in new manifestations now, but perhaps they also reveal how the British perceived external influence (both then and now). Was the resistance to early modernism purely a result of the comfort of familiarity? Perhaps there are other underlying reasons of nationalistic interest, although this may easily also be entirely speculative.

0 notes

Text

Early Modernism & Emigré Architects

While modernism began to develop slowly after making its way to Britain during the interwar period, it was consistently faced with high levels of resistance from the British, who despite embracing some modernist efforts such as those proposed by early health centers and related philanthropic projects were ultimately steeped in familiarity and highly resistant to changes to the existing architectural typologies. In general, it was a strange resistive but embracing reaction to modernism felt in Britain.

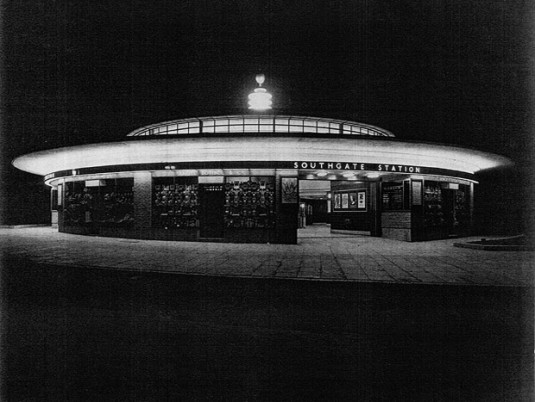

Southgate Station (1931 - 1932), Charles Holden

From 1931 to 1932, Charles Holden spearheaded a project with a series of manifestations to redesign some London Underground tube stations. These primarily used classical forms and references to Wren’s city churches in materiality and treatment of atmosphere, but ultimately were addressing very modern needs of inner-city transportation.

The 1930s introduction of the automobile proposed new methods of transportation and the problem of relating these various methods of transportation to each other to create a multi-layered network. Furthermore, given the necessity of transport and it’s inseparability form urban life, these tube stations created a renewed perspective of social space and its significance. These could be comparable to a type of contemporary “religion” (although this word is used loosely), giving weight to city infrastructure due to it’s social necessity.

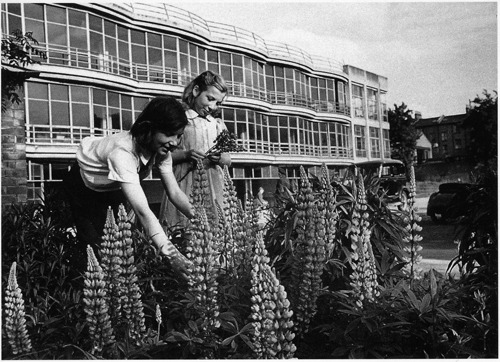

Perhaps the most significant changes brought about by modernism are in its effects on lifestyle. The Peckham (Pioneer) Health Centre (1933 - 1935) designed by Sir Own Williams is one of the projects that marked these changes.

Considered the first modernist project (proper), this was a philanthropically funded project targeted at the general community. This project is a manifestation of modernism’s marriage of technological interest and socio-political agenda, with extensive use of glass and large “healthy” spaces with fresh air and ample exposure to natural light that intended to promote healthy habits.

The model for this endeavour was based largely in prevention and the anticipation of illness or ailments. The effort was preemptive, not posthumous. Ultimately this was an experimental project that hoped to achieve social progress and a general improvement in the quality of life by means of technological progress.

Interestingly, while these types of projects were largely successful, some other projects that targeted similar agendas were not nearly as well received. For example with Highpoint I & II (1935 - 1938) by Berthold Lubetkin, which challenged existing definitions of publicness and privacy, there was much skepticism in its success and how these changes to the perception of public and private would affect living. Even in some design decisions such as the cantilevered shelter (below), Lubetkin was ridiculed for his ambition, and in response added a caryatid to feign structural support.

Another example of this resistance can be seen in Ernö Goldfinger’s 2 Willow Road (1939), which was modern in design, but ultimately attempted to disguise it’s modern approach using materiality. The building featured a brick-cladding that was meant to act as a kind of “buffer” for the radicality of its modernist agenda.

Considering the difference in reaction to the various types of projects, one begins to question why these reactions were so varied. Ultimately they were responses to social patterns and technological advancements, and so the disparity in reception is curious. While some explain it as a desire for familiarity, and the overall resistance to change that was a product of an International Style (and thus non-nationalistic), perhaps this is not a fair assessment as this resistance was in fact selective, and not homogenous across projects.

0 notes

Text

WWI: the first global, industrial and colonial war

Waterlily house in Kew Gardens

Visiting Kew Gardens and viewing the various greenhouses as attractions, their original purpose feels far removed. Seeing how beautiful and pleasurable these facilities are, its “dark” past as a result of colonisation’s interests in the exotic is almost inconceivable. In retrospect, these are almost a precursor to the later evolved modernist concept of architecture as an essential public service. However much these archetypes have evolved, it is undeniable that they are a modern manifestation of architecture’s pursuit for control.

Originally research facilities for the exotic botany that was imported from the colonised countries, these greenhouses allowed controlled climates to be produced for these flora and fauna, and were in some sense an exhibition of Imperial power.

World War I was ultimately a war of industry and over colonies. As a modern phenomenon, this ultimately was a type of “project” aimed at modernisation.

0 notes

Text

Industrialisation - Environment and Society

Early 19th Century industrialisation in Britain saw changes to material and infrastructure. While the idea of industrialisation is something of a blanket concept, it can be understood in two parts: production, and communication.

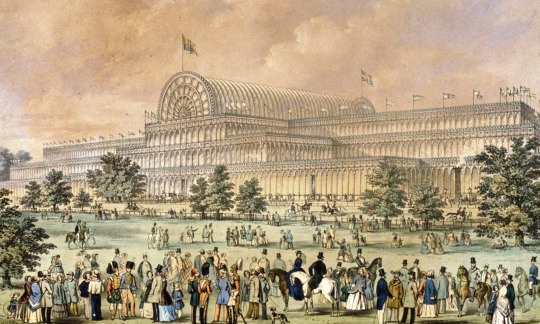

A project that is typically used to characterise the epitome of industrialisation and its effects is Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace that was constructed for the World’s Fair of 1851.

Inspired by Chatsworth Greenhouse (1840 - 1841), this was considered a structure that was not necessarily architectural.

While architectural style was previously a primary method of asserting “dominance”, this distinctively style-less structure displayed dominance and significance more in its purpose and what it represented: the height of globalisation, colonisation, and Imperial prowess.

Furthermore, in lacking architectural qualities, it was revolutionary in its display of industrial potential. The structure was entirely pre-fabricated and assembled on site as a kind of “kit”, and later dismantled and removed after its purpose was served. This temporality and emphasis on speed of production was unprecedented, and revealed the potential of industrialisation and how it could be used in the creation of social spaces for events as significant as the inaugural World’s Fair.

The arts and crafts movement emerged in the mid to late 19th Century as a response to industrialistion’s destructive impact in hopes of reviving the value of craftsmanship and artisanal production. This movement had a strong interest in material integrity and the “liberation” of craft and creativity by “rejecting” many modernist principles and methods such as mass-production, engineering, and industrial materials, instead embracing the everyday life and the humanity of design and production.

The Red House (1859 - 1870), Philip Webb and William Moris

While the Arts & Crafts movement is often perceived as a complete rejection and polar opposite of industrialisation, perhaps the better explanation of this movement is that it proposes an alternative modernity. And so ultimately it can be understood as a method of production with a future-oriented outlook that does not necessarily reject the past or the existing trajectory of modernism, but has instead taken a critical standpoint that responds to previous endeavours while selectively utilising specific methods or concepts.

0 notes

Text

Ruins & Ruination

The idea of degradation as we know it proposes that nature and the built environment are opposing forces where one thrives only when the other fails. Ruins are understood as products of a gradual and extended process, where nature overtakes man’s ability to tame it (as discussed in Destruction and Opportunity).

Previously, with many of the projects that John Nash, the architect of the moment, had undertaken, the “picturesque” entailed a careful curation of natural and physical landscapes, typically favoring the built form and controlling the natural environment. However, when John Soane emerges in prominence in the late 18th Century, he proposes a more romantic fascination with architecture and nature, where the two are complementary and not opposing each other.

To first explore this, we first looked at the portrayal of architecture’s relationship with nature through history, and more specifically, in painting and pictorial representation.

Beginning with an early painting using raised linear perspective, Christ Giving the Keys to St. Peter (1481 - 1482), by Pietro Perugino, this image shows us a view of nature being secondary to the built environment, recessed into the furthest part go the image, and even still depicted as tame and “cultivated”, creating the ideal backdrop setting.

Compared to The Building of a Palace (c.1514 - 1518), by Piero di Cosimo - which is represented in a similar manner with a raised linear perspective, and composed with human activity as a foreground, architecture and the built form as the immediate backdrop in the middleground, and the landscape as the furthest background -, we begin to see the change in setting, where the overall landscape is not fully built and constructed with tiled flooring, but instead is somewhat “seamless” in that it is raw and in unison with human activity.

This second image (The Building of a Palace) also highlights the significance of building and construction in the production of a built structure, with the focus of the image being the labour being input to the final built form. In this image, we see construction and conception (of a built form) as complementary forces. They are interdependent and concurrent activities.

Later, however, with the rise in interest in the concept of disegno, we begin to see the growth of the divide between construction and conception. This can even be seen as the beginnings of the studio process or “studio culture”, that promotes the “drawing forth of an idea”, entailing that built structures must be planned and developed via a methodogical design process, transferring the two dimensional world into a three dimensional tangible reality. This idea of drawing and design was completely novel, as built structures were previously more “spontaneous” and unplanned, evolving constantly as construction was carried out on site.

As we see in some Romantic work such as Nicolas Poussin’s paintings like Landscape with Diogenes (c. 1647), nature’s role becomes much more primary, pushed to the foreground. Architecture in this representation becomes more of a supplementary supportive element, placed in the composition so that it is less accessible, crowded out by the sprawling landscape that has become something of monumentality - the primary element that is instrumental to architecture’s setting.

This view of architecture and nature leads us to the unification of the two in the projects of William Kent, one of the first designers of nature, who used follies to enhance and create a type of “nature” set in an architectural landscape. This attempt to coalesce nature and architecture created a seamless unification of built and natural, implying that neither existed before the other, but instead that they evolved as codependent forces.

In addition to this idea of disegno, there is also the idea of experience as instrumental to influencing design decisions - a development derived from the philosophical school of thought of empiricism.

Rousham House and Garden (1738 - 1741), William Kent

John Soane

Interested in re-engaging the site and studying the relationship between architecture and nature, John Soane aspired to creating an atmosphere - not a place necessarily, but an inhabited space (a space in its own right). Soane proposed a view of the ruin as document, existing the the past, present, and future, not merely as a fragment of the past as per its typical readings. His interest in atmospheres included a consideration of temperature, light, sounds, and smells as valuable measured components in designing architecture.

Interested in creating the picturesque, Soane was known to have critiqued Nash’s idea of the picturesque, which he perceived as instrumentalising the picturesque (adapting the picturesque of landscape painting) and thus not a truthful development of the picturesque; his interests reveled interpreting themes of landscape painting and adapting them to built form, not choreographing using types of pônt-de-vue and other “follies”.

0 notes

Text

Metropolitan Improvements

Learning about the history of Regent Street and Trafalgar Square (and other associated projects), we begin to understand more clearly how architecture has served as a method for reinforcing or implementing social hierarchies. Furthermore, drawing comparisons between Nash’s endeavours during the Regency and earlier development

0 notes