Do I believe in God?Do I think God's a myth?Am I an atheist?An agnostic?A Christian?Well, the short answer is "yes". Visit this blog's new home on Pillowfort!

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

This blog has moved!

This blog is now hosted at Pillowfort. Most original content from this blog will be migrated over there, and all new content will be posted there.

0 notes

Text

Donald Trump is exactly the kind of person that Jesus would have thrown out of the temple and beaten with a stick, and the fact that so many self-identified Christians want to put him in office tells you pretty everything wrong with white American Christianity.

267K notes

·

View notes

Photo

“If you’re going to walk in this faith, you have to be willing to do it in season and out of season. When it’s popular, when it’s not. When people are with you, when they are not. When it’s politically acceptable, and when it’s not. Your job is to speak to them. Whether they listen is not your concern. Saying something is not an option. You can’t see injustice, and say nothing. You can’t see abuse of other human beings, God’s creation, because of their race, their creed, or their sexuality, and not say something. You can’t watch religion be used as a tool of hate, and say nothing. The prophetic call then and now demands that we say something. Not based on popularity, not based on whether you’re going to be heard, but based on God’s initiation, and God’s summons to speak.”

– Rev. Dr. William Barber II, Wild Goose Festival 2013

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

rich republicans: Sodom’s sin was homosexuality!!

me: no, actually, that’s just a headcanon that you’re confusing as canon.

me: like, sorry for spoilers, cause you obviously haven’t gotten to Ezekiel yet, but… “Now this was the sin of your sister Sodom: She and her daughters were arrogant, overfed and unconcerned; they did not help the poor and needy.” -Ezekiel 16:49 (NIV)

rich republicans: like the days of Sodom and Gomorrah, so shall the last days be!

me: well ain’t that the truth.

me: you sodomites.

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

So this isn’t just to say the easy “hey the context was different, so *shrug*” thing that a lot of people do, but if Christians would actually read the new testament, particularly the epistles but also a lot of what Jesus said, as one part of an ongoing conversation about just what it is that the fledgling movement meant — and particularly what it meant in the context of imperial domination — instead of assuming that the authors were creating ex nihilo prescriptions for the ideal christian life, then so much shit would be much easier to resolve and would make a hell of a lot more sense

635 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bree Newsome on Nationalism as theology

98K notes

·

View notes

Photo

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The truth is, you can bend Scripture to say just about anything you want it to say. You can bend it until it breaks. For those who count the Bible as sacred, interpretation is not a matter of whether to pick and choose, but how to pick and choose. We’re all selective. We all wrestle with how to interpret and apply the Bible in our lives. We all go to the text looking for something, and we all have a tendency to find it.

So the question we have to ask ourselves is this: are we reading with the prejudice of love, with Christ as our model, or are we reading with the prejudices of judgment and power, self-interest and greed? Are we seeking to enslave or liberate, burden or set free?

… If you want to do violence in this world, you will always find the weapon. If you want to heal, you will always find the balm. With Scripture, we’ve been entrusted with some of the most powerful stories ever told. How we harness that power, whether for good or evil, oppression or liberation, changes everything.”

- Rachel Held Evans, Inspired: Slaying Giants, Walking on Water, and Loving the Bible Again

552 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“We are sons and daughters of the living God, not business partners who have bargained to avoid some coming punishment.”

– Michael Howard

2 notes

·

View notes

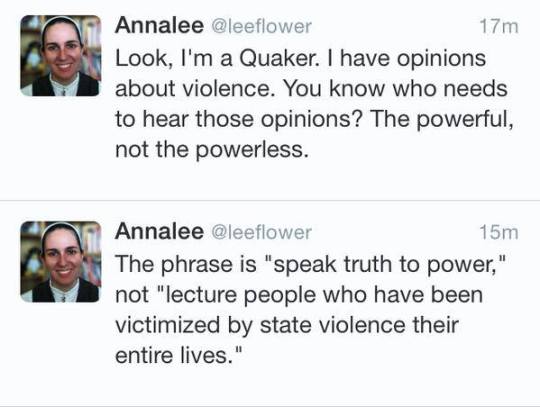

Photo

#i can choose nonviolence for myself from my own social position. #i can choose to stand alongside others who have chosen nonviolence. #i can explain why i choose nonviolence if people ask. #but if oppressed people do not choose nonviolence #my place is to help end the oppression they're responding to in the first place #not to condemn how they're responding to it. [x]

31K notes

·

View notes

Text

“The Bible doesn’t always agree with itself. As Timothy Beal put it, ‘The Bible canonizes contradiction.’

While these disparities may cause modern-day literalists to squirm, the authors and compilers of Scripture saw no need to iron them out. In fact, Jewish readers make a point of highlighting the Bible’s contradictions to spark discussion and debate. …

When God gave us the Bible, God did not give us an internally consistent book of answers. God gave us an inspired library of diverse writings, rooted in a variety of contexts, that have stood the test of time, precisely because, together, they avoid simplistic solutions to complex problems. It’s almost as though God trusts us to approach them with wisdom, to use discernment as we read and interpret, and to remain open to other points of view.

‘The iconic idea of the Bible as a book of black-and-white answers,’ wrote Beal, ‘encourages us to remain in a state of perpetual spiritual immaturity. …In turning readers away from the struggle, from wrestling with the rich complexity of biblical literature and its history, in which there are no easy answers, it perpetuates an adolescent faith. It keeps us out of the deep end, where we have to ‘ride these monsters down,’ as Annie Dillard put it, trusting that it’s not about the end product but the process.’ ”

- Rachel Held Evans, Inspired: Slaying Giants, Walking on Water, and Loving the Bible Again

584 notes

·

View notes

Photo

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

You are responsible for your religion.

This is a revivalist rant inspired by fundamentalist Christians bashing my gay trans brother, but it goes for everyone, mmkay?

You are responsible for your religion.

You are responsible for the morals you take from it, for the ways it impacts your life and those around you. You are responsible for the way you choose to practice. So often I see Christians using religion to justify their homophobia and sexism, or folkish Heathens using their religion to justify racism, but it isn’t Christianity or Heathenism that’s causing pain to other people; it’s the people who choose to interpret them that way.

(Heathens and Christians: I am sorry I used you as an example. Y’all have some pretty weird compatriots and they were the most obvious examples I could think of right now, but that doesn’t reflect on you, just on your weird compatriots.)

Many religions have their roots in very old cultures, with completely different customs and ideals than the ones our culture today follows. That holds true for us polytheistic types as much as it does for Christians. The Old Testament contains many things that are outdated and appalling in the culture of today. The myths and stories of Hellenic Polytheism come to us via an incredibly sexist and archaic culture.

You are responsible for how you choose to bring your religion into the present.

Old stories and old religions contain justifications for violence, slavery, racism, sexism, and a gigantic slew of problems that our culture today is still overcoming. That doesn’t make them bad, but it does mean that we should always be conscious of what we’re choosing to keep as vital to the religion and what we’re choosing to discard as outdated and relevant only to a culture that no longer exists.

You are responsible for your religion. You are responsible for the choices you make, or fail to make, in bringing your religion into the present–and you are responsible for the impact those choices have on the people around you.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

have y’all ever had communion bread that was just so….nasty? like i know we have to suffer as christians, but do we really need to have whole wheat bread as the body of christ?

220K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Text Is Not In Heaven: Fan Works, “Word of God,” and Midrash

In Jewish tradition, there’s a story from the Talmud in which two rabbis disagree over how to interpret scripture.

“If I am right,” declared Rabbi Eliezar, “let the carob tree outside testify to this fact!” The tree pulled itself up out of the dirt and walked 600 feet away.

“A tree has no authority to interpret Torah,” replied Rabbi Joshua, speaking for himself and the other Rabbis, who all agreed with him. “So we pay no attention to a carob tree.”

“If I am right,” said Rabbi Eliezar, trying again, “let the river testify for me!” And immediately, the river began to flow backwards.

Rabbi Joshua shrugged. “A river has no authority to interpret Torah. So we pay no attention to a river.”

Rabbi Eliezar was growing frustrated. “If I am right, let the very walls of this study hall bear witness!” The walls buckled and cracked, threatening to cave in.

Rabbi Joshua sighed, and rebuked the walls. “When Rabbis are discussing Torah, who are you to interfere?” The walls stilled, and did not collapse further.

Finally, Rabbi Eliezar called out, “If I am right, let Heaven itself say so!”

A booming voice called out from Heaven, saying “Why do you argue with Rabbi Eliezar? He is right. He has always been right!”

Rabbi Joshua shook his head. “The Torah is not in heaven,” he said, referencing Deut. 30:12. “It was given to us, on Mt. Sinai. Therefore, we pay no attention to a voice from Heaven.”

Hearing this, God laughed and said, “My children have triumphed over me!” He rejoiced, knowing that instead of being content to passively await wisdom handed down from on high, his children were capable of reasoning and thinking things through for themselves.

Storytelling is inherently interactive. That’s part of its very nature, on a fundamental level. The story does not exist on the page or the screen – all that’s there is a bunch of black squiggles or color-flashing pixels. It’s only in the mind of the reader or viewer that it becomes something more. And every reader or viewer will invariably bring their own interpretations to the story, based on their own values and experiences. Thus, there will be as may different versions of the story as there are readers – some will differ dramatically, some will be almost exactly the same, but no two will be 100% identical. So literally the only way to prevent different versions of a story from existing – the only way to safeguard the author’s “one true” interpretation – is to lock it away where no other human being will ever see it. The instant an author allows another person to engage with their work, they are permitting – no, inviting – them to become co-creators in a collaborative endeavor.

“Death of the Author” – the position that a text stands on its own, apart from its author – has been a staple of literary criticism since the mid 20th century. That’s not to say that the author’s interpretation of the text is wholly irrelevant. It’s just no more (or less) authoritative than anyone else’s interpretation. For those who cling to the notion that “Word of God” trumps all, countless cases of authors contradicting themselves throw quite a spanner into the works. And fandom has tacitly acknowledged the authority of reader interpretations for centuries, as shown by the nearly unquestioned acceptance of Juliet pining for Romeo from her balcony, Sherlock Holmes’s pipe and deerstalker cap, and Cinderella’s glass slippers.

But as the story at the top of this post illustrates, the notion that authority ultimately rests with the readers, not the author, goes back much further and is in fact part of sacred tradition. Far from being disrespectful, the capacity for re-telling and re-interpreting a sacred text is an integral part of what makes it so powerful in the first place. During the 1st century CE, in the wake of the destruction of the Second Temple, the Jewish Rabbis embraced a type of Biblical interpretation called midrash. This involves creatively engaging with the text to discover how it can speak to present circumstances.

From The Case for God by Karen Armstrong (terrible title, wonderful book):

Jews had long realized that all religious discourse was basically interpretive. They had always looked for new meaning in the ancient texts during a crisis.

Scripture was not a closed book and revelation was not a distant historical event. It was renewed every time a Jew confronted the text, opened himself to it, and applied it to his own situation. The Rabbis called scripture miqra: it was a “summons to action.” No exegesis was complete until the interpreter had found a practical new ruling that would answer the immediate needs of his community.

Revelation did not mean that every word of scripture had to be accepted verbatim, and midrash was unconcerned about the original intention of the biblical author. Because the word of God was infinite, a text proved its divine origin by being productive of fresh meaning. Every time a Jew exposed himself to the ancient text, the words could mean something different. […] The rabbis believed that the Sinai revelation had not been God’s last word to humanity but just the beginning. Scripture was not a finished product; its potential had to be brought out by human ingenuity, in the same way as people had learned to extract flour from wheat and linen from flax. Revelation was an ongoing process that continued from one generation to another. A text that could not speak to the present was dead, and the exegete had a duty to revive it.

In some versions of the Talmud, there was a space on each page for a student to add his own commentary. He learned that nobody had the last word, […] and that while tradition was of immense importance, it must not compromise his own judgment. If he did not add his own remarks to the sacred page, the line of tradition would come to an end. […] “What is Torah?” asked the [Talmud] Bavli. “It is the interpretation of Torah.”

If this is a profoundly reverent approach to sacred texts, how much audacity must a modern-day writer have to say that their writing is somehow above such examination and re-interpretation by their own devoted fans? If fanfic and fan interpretations are invalid, this means that the text in question is more sacrosanct than Jewish and Christian scriptures (perhaps other religions’ as well, but that goes beyond my area of study). It presents the author’s metaphorical “word of god” as more definitive than what many revere as the real-world Word of God. It demands greater deference from fans than, per sacred tradition, God even wants from the faithful! Consequently, I can’t respect any writer who speaks against fanfic, or disparages fan interpretations. And I can only laugh at readers who willingly surrender their own fannish agency by doing likewise.

Long before television, movies, or the printing press, storytelling was a communal practice. Stories changed with each re-telling, sometimes accidentally, sometimes on purpose. They were living, evolving things, carrying far more meaning and potential than shone through in any one telling. Fan communities who produce new interpretations and fanfics restore life to stories which have been artificially frozen in place. As MIT professor Dr. Henry Jenkins put it, “Fan fiction is a way of the culture repairing the damage done in a system where contemporary myths are owned by corporations instead of by the folk.”

So, is Hermione Granger black? Is Dean Winchester bi? Is Sheldon Cooper autistic? In some cases, the powers that be approve of such interpretations. In others, they vocally oppose them. Most of the time, they don’t comment one way or another. And in the end, it doesn’t matter. Because the text is not in heaven – therefore, we pay no attention to a “Word of God.”

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“I take the Bible too seriously to take it all literally.”

– Madeleine L’Engle, A Stone for a Pillow

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Argumentum ad Millennium Falcon

In Star Wars (I’m talking original, Episode IV here), Han Solo famously boasts that his spaceship, the Millennium Falcon, is so fast that it flew the Kessel Run in less than twelve parsecs. There’s just one problem – a “parsec” is not a unit of time. It’s a unit of space. Han’s line is like bragging that your car is so fast, you drove to church in less than three miles. It simply doesn’t make sense.

Except, well, fans are clever. Very clever.

Over the years, fans came up with a theory. The Kessel Run, they reckoned, goes through an area of space containing many gravity wells. A safe route gives each gravity well a wide berth, to avoid being sucked in, but weaving in between them all results in a long route. The closer you can get to each gravity well, the shorter the route will be, but the higher the risk of getting sucked in. The closer you get to a gravity well, the faster your ship needs to go to break free again.

So you see, shaving the length of the Kessel Run down to only twelve parsecs required getting really close to some of the gravity wells, and that required a lot of speed to survive. Et voilà, Han’s “parsecs” comment was about speed, after all! It all makes sense!

But is that what George Lucas had in mind when he wrote the line? Did fans merely reconstruct the explanation he’d been thinking of all along? Does this mean that there wasn’t actually any error in the first place? Yeah, right.

The lesson here is, of course, that just because someone can come up with a clever way to explain away a problem doesn’t mean that there wasn’t really a problem in the first place. Indeed, the only reason such a clever solution was necessary in the first place is because there is a problem.

The connection to religion should be pretty obvious at this point, but I’ll spell it out anyway.

Biblical literalists (never mind their awfully selective literalism) love to claim that the Bible is completely free from errors or contradictions of any kind. And when backed into a corner, they often manage to concoct some solution or another. But again, does the ability to invent a clever explanation mean that the problem itself never really existed at all? Did Jesus celebrate Passover with the Essenes, so he could still be killed on the (Pharisees’) Passover? Did he cleanse the temple twice? Did Matthew give Joseph’s lineage, while Luke gave Mary’s?

I call the idea that invented solutions can negate the existence of the problem “argumentum ad Millennium Falcon” because the logic shares the same flaw as supposing that George Lucas was alluding to a cluster of gravity wells all along. Star Wars fans managed to explain away this line within a few decades (at most). Christians have had a couple millennia. It would be more surprising if those committed to literal readings hadn’t come up with a decent number of excuses in that time. It doesn’t make literalism true.

#bible#biblical literalism#christian fundamentalism#logical fallacies#millennium falcon#original content

1 note

·

View note