— ☆ hi i’m eva and i write about bts sometimes! — 𝜗𝜚 mast. —

Last active 60 minutes ago

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

i used to pray for times like these

PARK JIMIN??? JEON JUNGKOOK???? HELLO?????????

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

© bambitae 2025 - please do not copy, claim as your own, or translate without permission. all readers can enter but if you are not 18+ please mind the warnings and refrain from interacting with explicit content.

legend: angst 𓆡 | fluff 𝜗𝜚 | smut ৎ୭ | personal favorite ✩

series: ongoing ✢, hiatus ✾, completed 𖡎 - titles with no symbol before them signal the work is in progress

KIM NAMJOON

Welcome to Wedding Hell ৎ୭ fake dating!au

27 might be too young to marry to some, but not to a man trying to slither into his grandfather’s will. When your best friend since college asks you to play the part of his fiancée, you’re not in a position to refuse. Having freshly broken up a 5-year relationship, you find accompanying him home for his cousin’s wedding might be just the change of pace you need. You have been friends for almost a decade now, after all, nothing could go wrong… right?

The Invitation ৎ୭

Kim Namjoon has had a very rough day. When he encounters an old friend on the street and receives an invitation to his party, he doesn’t know he’s in for an even rougher night.

Vengeance is Mine, All Others Pay Cash ৎ୭ partners in crime!au

Upon his return to Korea, Kim Namjoon, now no longer a powerless kid, sets out to get his revenge on the loan shark who ruined his family and along the way meets you — a girl who wants to accompany him on the hunt, with a vendetta of her own.

KIM SEOKJIN

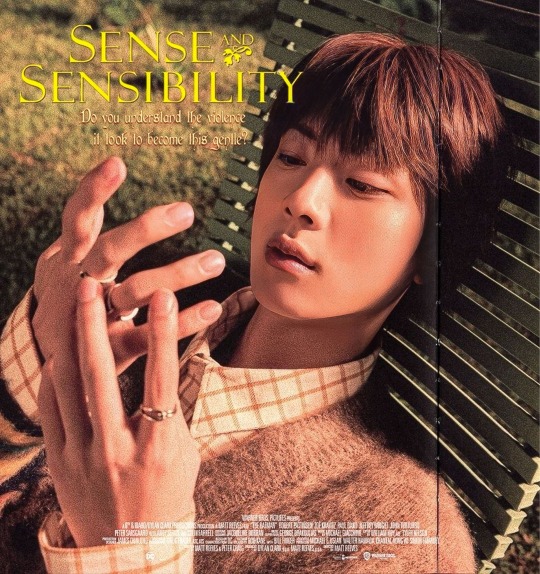

✢ Sense and Sensibility 𓆡, ৎ୭ age gap!au, summer romance (ft. Taehyung)

The worst thing that could happen on your summer visit to Santa Barbara was encounter your college friend’s fearsome stepfather — now, stranded with a thirty-something man instead of the silvery codger from your imaginings, you find yourself with a problem: your friend keeps delaying her return home and the two of you have to live in the same big, empty hacienda for the entirety of six long weeks.

prologue

Gifted 𝜗𝜚, ৎ୭ idiots in love, roommates!au

You have been living with your roommate for a year before you realized his advances have never been jokes — and all it took you to to reach this epiphany was him quite literally pouncing on you.

He’s Just Not That Into You 𓆡, ৎ୭ fwb!au

What is there to misunderstand? All those guys have never been into you, and especially that prissy frat boy Kim Seokjin. It’s just hard to get that through your head when, once again, he begins gracing your sheets after an ugly breakup.

The Edge of Seventeen 𝜗𝜚, ৎ୭ exes to lovers!au

The end of 2017 was the time when the two of you broke up. Now, eight years later, you both reminisce about your puppy love and college years while stranded in a café during a storm.

High Score ৎ୭ game rivals to lovers!au

Kim Seokjin walks into an arcade and is struck with the finding someone has beat his high score. He doesn’t believe this, and he has to find this cheater and have a word with them.

MIN YOONGI

Remember Me 𓆡, ৎ୭ amnesia!au (ft. Hoseok)

After an accident, your mind is addled with amnesia, and there are two completely opposite guys both claiming to be your boyfriend. You know neither of them and remember nothing they try to convince you happened; nonetheless, you must uncover which one of them is telling the truth and why they are so fiercely feuding over you.

No Hard Feelings 𝜗𝜚, ৎ୭ fwb, neighbors!au

Min Yoongi always found it indescribably odd, the human need for commitment; every one of the relationships he’d attempted had been a fluke and he’s long lost the desire to try romance. That’s why he finds it so puzzling when he begins sleeping with you, the sweet girl from next door, and for the first time in his life begins experiencing stupid emotions like affection, jealousy, and the urge to buy flowers.

I’m Thinking of Ending Things 𓆡

Yoongi has been thinking of breaking up with you for a long while now, but he still hasn’t found a good way to reveal the reason for his sudden change of demeanor.

The Piano Teacher 𓆡, 𝜗𝜚, ৎ୭ brother’s best friend!au, enemies to lovers

Running on limited time to learn to play your aunt’s favorite song on the piano before she passes away, you ask the only person you trust to teach you: your brother’s infuriating best friend who has had a knack for annoying you as long as you could remember. Perhaps giving the cocky bastard any sort of authority over you had been a great mistake, but it’s only when you spend time alone with him for the first time that you realize there’s a good guy hidden in him beneath all that sarcasm.

JUNG HOSEOK

Remember Me 𓆡, ৎ୭ amnesia!au (ft. Yoongi)

After an accident, your mind is addled with amnesia, and there are two completely opposite guys both claiming to be your boyfriend. You know neither of them and remember nothing they try to convince you happened; nonetheless, you must uncover which one of them is telling the truth and why they are so fiercely feuding over you.

The Wonder 𝜗𝜚 childhood friends!au

You had always wondered what a relationship with Hoseok would be like. After all, you had never been such close friends that you would never consider it. It’s on a group trip that you try to test this question out, but you don’t realize all the emotions he has been harboring throughout all these years.

Definitely Maybe 𝜗𝜚, ৎ୭ fwb!au

Nobody takes Jung Hoseok seriously, not even himself. Everything he does is careless, from his relationships to the jobs he can’t seem to hold down; this is precisely why everyone’s so puzzled when you fall for the resident clown, most of all he, who had already explained he wants nothing serious when you began seeing each other.

Summer Strike ৎ୭ strangers to lovers!au

You’re visiting your grandparents’ house for the summer and find they had hired a new gardener; you shouldn’t be feeling this giddy about a crush in your adulthood, but it’s too much fun sneaking around in the bushes for you to keep a cool head.

PARK JIMIN

The Glory 𓆡, ৎ୭ former rivals to lovers!au

Now that he has become a famous dancer, Park Jimin visits the dance studio where his fame took root and finds that his former rival has taken the role of an instructor, which is an incredibly lucky coincidence, as she’s the only person he can confide in about his career-threatening injury and ask for help.

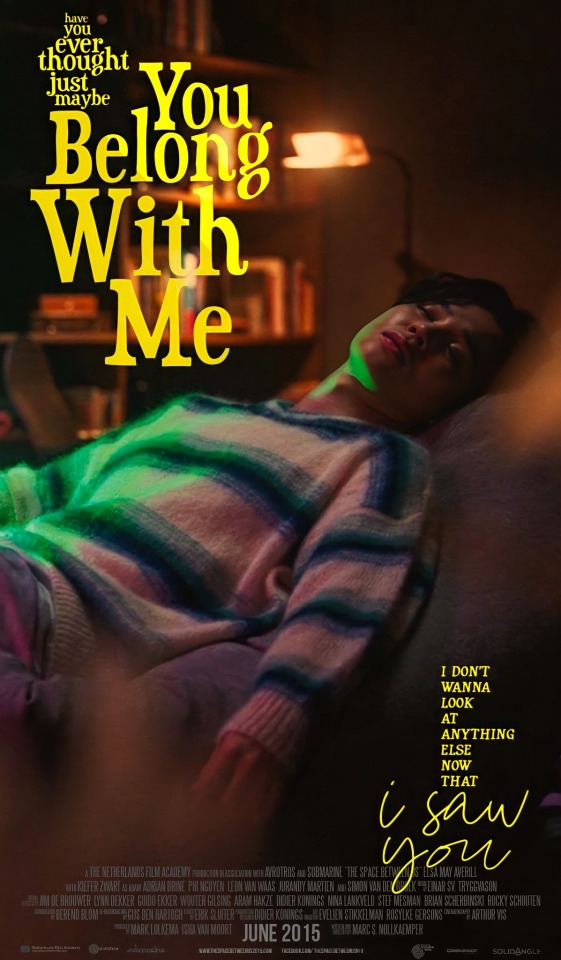

✾ You Belong With Me

When a cynical good-for-nothing, Jimin, sees the girl he was in love with a year after he’d quit gardening for “Bright Horizons”, the luxurious development she resides in, all his feelings come rushing back, along with the harrowing memories of what had happened in that gated community last summer; all the while he meets a mysterious man who claims he sees the potential for show-business within him.

When the Camellias Bloom ৎ୭ one night stand, childhood friends!au (ft. Jungkook)

After three years spent in college, the former trio having gone completely separate ways, you meet your two best friends from childhood and reminisce over drinks. One too many, and you’re suddenly trapped between them in the most unexpected three-way of your life.

KIM TAEHYUNG

I Know What You Did Last Summer ৎ୭ blackmail!au

Kim Taehyung knows what you did last summer in Santa Barbara, knows about your immortal affair, and he’s wickedly excited about using it as leverage to get you into bed.

10 Things I Hate About You 𝜗𝜚, ৎ୭ there’s only one bed!trope

‘Brat’ is the only word you can think of to describe the guy who had joined your winter vacation last minute, after having been thrown out of his own resort following an abrupt argument with his hookup. You’re shocked you even share friends with this sort of loud-mouthed menace. But the terror culminates when you find your room occupied and have no choice but to spend the night in his.

The Ugly Truth 𓆡, ৎ୭ friends to lovers, cheating!au

Nobody will tell you like it is quite like your friend Taehyung; and he’s telling you your boyfriend’s a tool.

JEON JUNGKOOK

Ready or Not 𝜗𝜚, ৎ୭ (ft. Namjoon)

Jeon Jungkook has had enough of unreciprocated feelings; after having reached the description of the ideal man you gave him two years ago, he’s ready to finally ask you on a date, but he finds there’s another man vying for your attention — and it’s none other than one of his closest friends, Namjoon, the very guy he looks up to. He has to take care of this quietly, before you notice and are swept away by his newfound rival’s bookish charms.

Sheep With the Sharp Teeth ৎ୭

You had always thought Jeon Jungkook was a rather innocent guy, but it’s only after you catch him in the act with a familiar sorority girl that he allows his mask to slip with you and you realize an entirely foreign side to the younger boy.

When the Camellias Bloom ৎ୭ one night stand, childhood friends!au (ft. Jimin)

After three years spent in college, the former trio having gone completely separate ways, you meet your two best friends from childhood and reminisce over drinks. One too many, and you’re suddenly trapped between them in the most unexpected three-way of your life.

CREDITS: The banners used for this masterlist were made by @cafekitsune. Dividers can be found here and the ‘masterlist’ and ‘mdni’ banners here. As for making text gradient or multi-colored, please see this helpful guide.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

doesnt my job understand i have a blooming fanfiction writing career to work on

#the sisyphean task of writing a smut scene during the shift#feeling like the 10 Things I Hate About You counselor#bambi: other

23K notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! Just wanted to stop by and say I enjoyed reading sense and sensibility! ❤️❤️❤️

Thank you for stopping by and for liking it!! It means a lot! Hope you’re having a great day! (ˆ꜆ . ̫ . ). ̫ . ��ˆ)

0 notes

Note

Hey, I love your writing and hope to see more of your stuff soon, I was also wondering if you could recommend any fics or writers that have a similar style or that you just like, thank you and best of luck

Hi!! Thank you so much, I’m really glad you liked it, it means so much! ♡ More stuff will come out in the coming weeks, though maybe not as quickly as I would like, but I hope you’ll be patient with me!

As for recommendations, one of my absolute favorites to this day, even if they are inactive, is @winetae ! They have fics that are in absolute Tumblr hall of fame, if you ask me. @ smashin are, I think, no longer active on Tumblr but here’s a link to their AO3 account — definitely worth checking out if you already haven’t; even though we have very different writing voices, theirs is extremely unique and interesting to read. Unfortunately, other writers on Tumblr I remember enjoying are either deactivated accounts or it has been so long since I’ve been able to finds their fics anywhere that I simply forgot their user/fic title.

But I do have literary recommendations for you if you’ve enjoyed “Sense and Sensibility”. The fic began as a writing exercise in the first place and is (very visibly) modeled after the writing style of Aciman’s “Call Me by Your Name” and Tartt’s “The Secret History”, with a bit of Du Maurier’s “Rebecca” sprinkled in. If it’s “You Belong With Me” you liked, the voice of that one is modeled after “Paradais” by Fernanda Melchor, this one a bit more obvious because the plot is really just reimagining of that story with Jimin as the protagonist.

Hope I could be of help, best of luck to you too ˶ᵔ ᵕ ᵔ˶

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Sensé and sensibility is soooo good! I haven’t been this exited for a fic in a long time, do you know when you’ll be posting the rest? I can’t wait! All the best to you

It actually made my heart flutter to read this ask! I’m glad my writing was able to make you happy! I have been working on the first chapter for some time already as I have the story somewhat mapped out, but I’m a bit slow when it comes to actually putting the words down on the page, so I would say it will be ready in the next few weeks TT

Thank you so much for reading, all the best to you too!! ⸜(。˃ ᵕ ˂ )⸝♡

0 notes

Text

Sense and Sensibility: Prologue

➥ Synopsis: You reminisce about the summer of 2006, the time you were stranded in Santa Barbara with no company but your friend's stepfather, and the secret affair that had blossomed in the absence of the friend who had invited you to visit.

⇁ Pairing: Kim Seokjin x Female Reader (ft. Taehyung)

⇁ Genre: Drama, Angst, Smut, Age Gap!AU

⇁ 3.5k

⇁ Author's Note: this is finally done!! i've been working on this for a year and the prologue is finally done TT this work has seen me move six times before i was finally able to post it! i'm so excited! i hope you enjoy my blood, sweat, and tears and the 'call me by your name' influence left imprinted on me after finishing the novel - i am so happy that i could hug each one of you !!! ♡♡♡

“Well then.” The curt words, the bored sigh that came beforehand, the attitude.

You’d never heard someone use “well then” to say goodbye before. That’s what he’d told you on the day you met him, as he placed the one dented suitcase you’d brought before Maya’s bedroom door; a long, loud step back, bare foot slapping against the terracotta parquet. Then he disappeared down the high-ceiling hall, behind a potted palm, lustrous floor spidery with his own lanky, distorted shadow.

It is the first thing you remember about him, and you can still hear it today, “well then,” just the thought of it transporting you back to Santa Barbara, last summer, stepping out of the train to see him before the station, tan pillars rowed with arches and a flat, clay roof, colossal palm trees and the unclouded sky; and he, a stranger, with his billowy blue shirt, wide-open collar, opaque blazer limp on his arm, skin everywhere. Suddenly he’s shaking your hand, taking your suitcase, telling you Maya is staying a few days longer in Los Angeles with her aunt.

It may have started right there and then: the shirt, the rolled-up sleeves, aviator sunglasses gliding down his nose as he looked at a passing salaryman, palm up for a greeting.

The occurrence was a startling and gnarly one, and most of the ride to Riviera you remember by being terribly stiff and silent, perplexed whether you looked to the cigarette hung from his mouth or the soaring hillside through the window—the vistas of white stucco walls nestled in the mountains becoming closer and more tangible the farther you climbed up the twisty roads.

Stepfather you had known from the stories, the college friend who’d invited you there in another city: a strained scenario no matter which way you’d want to twist it.

You were a bit uncomfortable, after the diatribes you’d heard, having to do with his conceit and bestial cruelty toward Maya, and you were mad at her too for being too lazy to ring you and set you to arrive a few days after. You wondered, as the breeze mussed your hair and you squirmed on the burning seat, if you would even withstand those six long weeks you had promised her.

It was impossible in the first days you didn’t scorn and fear the stepfather a little bit, even as he drifted in and out of the house like a shadow, unobtrusive, remote from it for most of the day. Images conjured by Maya’s tales came alive every time you were in the same room as him, the first of many a tableau of him at the breakfast table: robed in velour, morning paper in hand, whipping you with a stare over the rim of his spectacles as soon as you stepped over the kitchen threshold.

Everything was similar to how you’d imagined it, the hostile air and white mug from Saks he began using after smashing his favorite in an argument they had, but instead of the silvery codger in your fantasies, senile and swivel-eyed, he was a man who couldn’t have been past thirty, slight in the face and alabaster skin stretched taut over his jaw and clavicle. Only at glimpses did it catch the golden Californian tan: a bit on his cheeks and forehead, over his jutting metacarpals and lithe fingers, on one of them a pale hoop you sometimes saw when his wedding ring slipped.

Looking back at that morning, the first breakfast you ate at his house and by far the most miserable, the worries plaguing you were vague and paranoid ones, spiraling like tentacles into the abysmal nothing. You remember eyeing the coffee he’d brewed to you, too afraid to ask where they kept sugar, and feeling like you’d made a terrible mistake when the jam slipped off your toast and made an ugly, crimson splotch on the china. When he’d apologized for not having a proper breakfast ready, “I don’t eat it myself, you see,” impersonal and hidden behind the text-condensed pages of The Wall Street Journal, your reassurance came much too quick and petrified, bubbling out of your mouth through a slew of unchewed bread.

Maya had made him out to be a brute, a tetchy old man; it was wise for you to be wary. For the whole meal, you thought of the broken mug, pitying Maya for having to call such a man her father.

Your spoon kept clanking against the plate. He put his mug in the exact same spot each time. Your legs touched once before he stood up and put his mug in the sink. Before he’d left for work, he told you smoking wasn’t allowed in the house, and he said it absently, looking at his watch, one foot already out the door.

Memories of the first time being alone in the hacienda are now murky, muddled with the sludge and sloth of forthcoming events, but the awe you felt exploring remains fresh. It was hard to believe you were in California, with the wood beams for a ceiling, endless archways for doors, the lord-like coastal view from the living room window.

Without having anything better to do, you meandered for most of the day, stopping to admire every painting hung on the white walls until an old Baroque piece beside the garden archway startled you. It was a Diego Velázquez, the portrait of little prince Baltasar on a horseback, and you knew selling your kidney wouldn’t have made you nearly enough to buy it.

“It’s a fake,” he had told you one morning, later, as he watched you gape at it from the patio. “But a good one. Even the slightest detail on the clouds are identical.”

“Have you ever seen the real one up close?” you asked as you studied the details on the plump horse, the billowing military sash wrapped around the boy’s chest.

“I have.” He was stubbing a cigarette, sinking into the embroidered pillows of the velvet-upholstered sofa. “It’s displayed in Prado.”

But you had already known that.

As it happened, he’d caught you on the patio, on the same sofa, when he came home that first day, curled up with a book you had stolen from his study, a cigarette in his mouth and tie so loose it bent clumsily to the side. He was much too sluggish for your apologetic fervor to faze him. “It’s alright,” he said and sat across from you in a wicker chair, dumping his blazer over the arm. “You must be bored.”

It may have even started then, with the way he lit his cigarette: good, bared forearms on his spread knees; eyebrows rumpled and smoke curling out his mouth.

“Have you called Maria?” he said after a time, and looked at you over the eyebrow.

“No,” you were stuttering, not having expected he would talk to you, “my phone has no credit.”

He dug into his pocket and fished out a cellphone, typing away on it as he blew smoke to the side. Afternoon sun streamed directly into his face, in such a strong light most people looked washed out, but his surly, angular features lit up with the warmth of near sun-down until it was a shock to look at him. He had leaned into the shadow of hacienda’s roof before you finished admiring him, eyes squinted as he handed you the phone with Maya’s contact on it.

“I’m sure you have a few things to talk about,” he’d told you and stubbed out his cigarette, and then he told you to ask if you ever needed the phone and, if he wasn’t there, to take the landline one in the hall, and with that he went into the house, not to be seen again until dinner. Even through the haze you can recall his curt murmur as he passed the prince Baltasar, “Well then.”

Prior to the first weekend in Riviera, the pictures arranged in your mind seem disjointed and hazy, but it is on that first Sunday when they come into razor sharp focus and he morphs from a discreet, eldritch figure floating through the hallways into a creature of flesh and blood, a real person with a beating heart. You too appear as somewhat of a stranger in these memories: gauche and oddly elusive because of all the anguish of being stranded in a foreign state and the chilling stories Maya had bashed into your head for the past year. It had taken you days to look him in the eye and speak without odd, wary pauses; and now all those times you had ducked into a room at the sound of his footsteps only embarrass you, especially because you now realize, long after the fact, that your attempts to evade him were far from discreet.

Maya’s stepfather didn’t appear to be the monster she had led you to believe, and only after the six weeks together and the long time after you parted, which you spent scrutinizing and obsessing over him, did you realize he too must have been frightened and bewildered, waiting for you to make the first move with hands folded on his lap, politely as a maiden aunt. You were an intruder in his house, a strange girl who seemingly had her mouth sewn and fell into long spells of staring directly at him. You were every bit of an anomaly to him as he was to you; an alien who was all of a sudden curling up on his patio and leaving breadcrumbs on his table in the mornings; a complete disruption. And still he had made every effort to host you until Maya came, despite not wielding any responsibility towards you.

After that first morning, the refrigerator had become plump with breakfast options and a warm pastry awaited you by the bread box after his early cigarette trips to the store, and it was often he recommended books, asked if you needed to use his phone, or otherwise apologized for Maya’s absence—something even she failed to do once you managed to get a hold of her. But all this he did with such a sour face, spoke in such an enervated monotone, that you were certain he only saw a huge bother in you. It was that first Saturday when this fear began to gradually dispel.

You had never realized, of course, that the hacienda would not be completely desolate on the weekends. You remember now, looking back, how on that first Saturday morning he was up and writing letters, not in his usual uniform but a pair of swimming trunks and a robe coming undone at the waist, and when you got downstairs, he was nearly finished and placing them into thick, cream-colored envelopes, a cigarette hanging at the corner of his mouth.

He swiftly plucked it upon noticing you in the doorway. “Don’t mind me,” he said; “this place should air out fine in a minute with all the windows this room has. Not that you should smoke inside just because you saw me doing it. The coffee and the hot dishes are on the sideboard, feel free to help yourself.” You said something about not minding the smoke, how all right with all of it you were, but he did not listen, he was looking down at a letter, frowning at something.

He didn’t seem to notice you, in fact, even when you sat across from him at the table, a little overawed at the brilliance of the breakfast presented to you: dishes of poached eggs, of bacon, and another of sausages and fried bread. There was tea in a grand porcelain tureen, and coffee, piping hot, in a similarly wonderful urn with two huntsmen in acryl, chasing after a deer. A cluster of grapes dangled from the dessert stand, surrounded by a ridiculous diversity of fruits—guavas and figs and pomegranate slices—but the tower paled in comparison to the one beside it, adorned from top to bottom with various cakes. It didn’t seem possible that he could prepare all of this by himself, and his disregard for the feast was perplexing. From the entire table he had taken only a cup of coffee for himself. And, it seemed, some grapes. The twigs lay barren on the saucer by his hand.

“Is today a celebration of some kind?” you said, unmoving at first, wary of bad manners. You didn’t know how hungry you were before you sat down.

But, “No,” he replied simply, unsheathing his pen. “It’s just a Saturday.”

It was strange to you to think that Maya, who back in Portland shared a dorm with you and bathed in communal showers, should sit down in her home on the hillside of American Riviera to a breakfast like this one, day after day, for her whole life probably, and find nothing absurd about it, nothing wasteful. You couldn’t fathom why she would enroll into a public university at all when she was accustomed to such banquets, but you now understood why she sometimes scrunched her nose at supermarkets and people dressed in secondhand, and were a little bit flurried.

You noticed he poured himself more coffee. You took a slice of ham. And you were afraid to wonder what would happen to all the rest, all that meat and fruits and the chocolate gateau, and the tea once it went cold. There were no menials in the house, no one to wait for the gift of breakfast other than the dustbins.

“Why even try to argue with a woman of such a feeble mind,” he said suddenly after a time, during which he wrote furiously, the paper all a sharp, messy hand. He set down his reading glasses, not looking you in the eye. He waited for you to raise your head. “It seems Maria is coming next Sunday, after all. She banged up her phone and lost her train ticket. Her aunt will drive her back here, and she’s not free until the weekend.”

The announcement startled you. “On Sunday?”

“If Maria’s aunt is to be trusted—and she’s not. I don’t understand why everything has to become so complicated.” He got up from his chair and lit a cigarette. “I’m sorry about this, I really am. You’ll have to make do for another week even though it’s uncomfortable.”

“It’s all right,” you said, sounding quite small. Suddenly your appetite was lost.

“I mean this very seriously.” He was looking out the window, into the courtyard and pool, at the indolent rose bushes swaying slightly in the wind. His robe was open now as he leaned on the windowsill. “She’s being extremely irresponsible, I can’t begin to imagine why she left you here all alone.”

“It’s all right,” you repeated. “Did she leave some sort of message for me maybe?”

He shook his head, a cigarette upon his lips. “If she did, her aunt omitted it.”

Neither of you said anything for a moment.

“So, what are you going to do?”

“Pardon?” Finally, you put down the heavy silverware.

“Are you going to wait for her until she comes?”

The question boggled you. Did he want you out of the house? But it would be a long way back to Oregon, and you had barely caught a glimpse of California. “If I’m not a burden on you,” you said, spineless.

He said nothing before coming to the table to put out his cigarette, the robe fluttering behind him. “Understood.” He took his papers, the conversation having seemingly left him sour. “Enjoy your meal.” Then he strode out into the hall, leaving you in the thick silence of the kitchen, alone among the plates of meat and dessert stands.

You tried not to be too curious, and after abandoning breakfast amused yourself with plans of taking a long walk to the East Beach, or reading, or even having a drink in West Mesa, on the terrace of a cafe with a good look at the ocean. It wasn’t until you were coming up to the bedroom to get dressed, sometime before noon, that you glanced through the window and realized he hadn’t left for work still.

Instead he lounged in the courtyard, along the edge of the pool, with his eyes closed and his back turned to you, and it startled you, what broad shoulders he had, the bare and wet skin, the slight quiver of muscles as he rested on both elbows, foot gently caressing the pool-water. For a moment he held it there, on the surface, unmoving, only to let it fall limp with a splash. Hair was sticking to his face; his swimming trunks clinging to the skin. Beside him lay his robe and his cigarette packet, as well as an empty glass, all scattered, and he seemed to care very little about the mess, instead tranquil, dreaming, slowly swaying backward as he soaked in the sun. He was a different person to the man writing letters in the morning.

For the first time it had struck you how handsome he was, and although you may have known this before, you were too afraid to think it. It would have been far more noticeable had his posture been less stiff or his gaze, behind the glasses, less shrewd. He looked almost young now as he stretched across the cantilever deck, younger than he already was, lingering for another moment before he dove into the water. There was a splash, a ripple. It all seemed very beautiful to you, how it danced and glittered in the sunlight.

You caught yourself by the window, peering at him from behind the curtains, and were promptly humiliated. You drew the curtains, the skin on your neck hot, and the back of your ears, and you didn’t know what to do with your hands or your feet or your reflection in the wardrobe mirror, prancing around half-undressed and with a wire poking out of your brassiere. You thought about how he could’ve looked up and caught you: the unwelcome guest, spying on him in nothing but her underwear. And what shabby underwear it was! You unhooked it the same moment and threw it in your suitcase, still burning.

The impression of looking battered was stuck on you even as you picked out your least worn swimsuit and a dress to go with it, which prior to coming here seemed rather Californian to you. Now it looked childish, too flowy, like a little girl’s dress. What did it matter if you looked silly? You didn’t know but you feared it, and as you twirled around and picked at the threadbare stitching, you only thought of how flustering it would be for him to notice the cheapness of the material, the slightly frayed hemline with a thread sticking out from beneath. Maya would have made fun of the dress, if she were here to see it. The thought alone made you swear not to wear it around her, perhaps never wear it again at all, and instead you dressed in a shirt and shorts, both fitting loose and boyish; they made you look plain but they at least didn’t make you look stupid.

You had just been packing your beach bag when a knock came at the door; it was him, changed out of his swimming attire and a towel on his neck. “Going somewhere?” he asked after a brief gust of silence, in which you stood there, staring stupidly at his face, and it wasn’t until he had spoken that you became aware, with a rush of color to your face, that you had blundered irrevocably in thinking he had come to reproach you, had noticed your watching him. You had made a fool of yourself looking so scared.

“Yes,” you said, stammering, your words tumbling over each other. “Yes, I’m going to the beach.”

“That’s nice,” he said; and he knew, you thought, he guessed you had done something wrong and inappropriate in his house, or in the very least finally pegged you as an odd person. It was in his eyes, the gentle, perhaps slightly pitiful scrutiny. “One of my nephews phoned me earlier. He and my sister will be coming for lunch and he asked for some sort of bracelet he borrowed to Maria. I thought to ask you to look for it, but it seems like you’ll miss them.”

“Oh. Yes, of course.” You were overly relieved, overly eager. “I’ll look for it. It’s no problem.”

“You don’t have to inconvenience yourself, it was my mistake to bother you,” he said, his voice even. “Go to the beach.”

“I have the whole day, it’s really no problem.” You were already pushing the door into a close.

He put his hand on it. “It would be easier to find, I think,” he said, reaching into his pocket for a photograph, “if you knew what it looked like.”

There was a ghost of a smile on his lips, fingers grazing your as he handed it over. And you knew that, by then, it had already begun.

#seokjin x reader#kim seokjin#seokjin fic#seokjin fanfiction#female reader#seokjin fanfic#seokjin angst#bts fanfic#bts fic#seokjin x you#seokjin x y/n#candy writes#bts imagines#i hope you enjoy#love you guys!!#♡

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

You Belong with Me

Synopsis: When a cynical good-for-nothing, Jimin, sees the girl he was in love with a year after he'd quit gardening for "Bright Horizons", the luxurious development she resides in, all his feelings come rushing back, along with the harrowing memories of what had happened in that gated community last summer; all the while he meets a mysterious man who claims he sees the potential for show-business within him.

Pairing: Jimin x Reader

Genre: Romance + Drama + Angst + Smut + Fluff

Word Count: 3.6k

|| Episode 01 of ? ||

i.

Tonight he saw you. Yoongi and he were pushing out of the cinema in a current of people when he saw you in a blue coat, mincing through the crowd. That stupid hot tremor mantled his cheeks, his chest and stomach; always new and horrifying no matter how many times he felt it. He called your name so quickly his voice ended a squeak, and the pedestrians around him became dense as statues as he charged through them until finally a pinch of your coat was in his fingers and you turned to look at him, the shimmer around your eyes sparkling under the pale streetlamp. He was bilious with panic. Beneath your skirted coat, your legs were naked and bristled with goose bumps, and he barely recognized you with your face made up.

“I’ve been looking all over for you,” he said. “Y/N. Call me, write to me.”

You smiled at him, a bit like you from last summer, nodded stiffly, and you were gone with a bang of the yellow cab door. He stood on the curb for what felt a long time, hands sweating in his pockets and the oppressive, sweltering desire gutting him as he thought of your slight eyelashes and voice and lissome fingers on his shoulder, until that prick Yoongi came and slapped him on the head, telling him to get a move on and not to be so fucking pathetic, and Jimin slapped him too, and the prick laughed in his creepy, gravelly voice and fished a cigarette out of his pocket and shoved it into Jimin’s hand and told him to come on, that he’ll buy him a drink, and to wipe off that pussy ass face and stop being a fucking idiot.

He took him downtown, to Jack Rabbit, a sorry little alleyway pub made of wood panels and suffering from cramped space and fusty cigarette air, and they sat at the bar across the bearded codger that tended it on uncomfortable oak stools; Jimin couldn’t understand why he insisted on coming there, because, honestly, the draft beer was too bitter and flat and the ancient pop music from the jukebox prickled his ears and the codger always spewed some pseudo-philosophical bullshit and bored him to death with his dull life spent in poverty and gloom—and, really, it was a bit humiliating to frequent such a dump. It was a mystery how it stayed running with barely any guests. Still, Yoongi dragged him there routinely and downed the beer as if he enjoyed it and entertained that annoying old man with sagging jowls and a pig gut. If the prick weren’t the one paying, Jimin would have fucked right off out of there.

They drank for hours, until both of them were red in the face and slumped over the bar; the hung glasses and shelved alcohol bottles spun violently, Jimin’s foot kept slipping off the footrest, and Yoongi shook him until he was nauseas. You’re a moron, he kept telling him. A fuckin’ dunce. Face it: she’s never going to be with a good-for-nothing like you. You think she’s gonna pick you over all the rich motherfuckers chasing her? Don’t be a damn idiot, Chimmy, save yourself the fucking time.

But Jimin knew all this and still he didn’t believe it. The problem was not that he mowed your lawn the previous summer or that he went to a shithole like Jack Rabbit because he had no money to buy himself a beer. The problem was he, that fuck-face, that disgusting richling and his sick obsession with you.

It was all Kim Taehyung’s fault, that’s what he wanted to tell Yoongi. Jimin’s only sin was not killing the fucker. Richling was crazy about you, and Jimin saw firsthand how for weeks the bastard spoke about nothing but screwing you, making you his, whatever it took; I’ll fuck her like this, he’d drawl, the same shit over and over again, eyes bloodshot from the alcohol, I’ll fuck her like this then I’ll flip her on her knees and I’ll bang her like this, and he would wipe the whiskey off his mouth with the flat of his hand and laugh like a psychopath. Then he would clamber to his feet at the edge of the pier and pull out his cock and piss in the river as he blabbered on about how he was going to ram into you, teach you a lesson, and then he would shove it back into his swimming trunks, sit back down, and roll a blunt with those same filthy hands that touched his penis, all the while Jimin laughed faintly and made the most of Taehyung turning his back on him to swig from the bottle and take another cigarette, puffing smoke at the relentless mosquitos that wouldn’t stop latching onto his arm.

It was all that bastard’s idea of a joke, just banter, drunk talk, or at least that’s what Jimin thought in the beginning during their first carousals down by the river, in the shadiest part of the small wooden platform, where the gnarled branches of the fig tree kept them hidden from the eyes of the watchmen and other residents of the complex, and most crucially Taehyung’s grandparents that would, in his own words, suffer a stroke if they saw their “little boy” drinking alcohol and smoking pot and who knows what other crap, and that with none other than a member of “the help.” A gardener, no less.

That would be an absolute scandal, a breach of trust that would undoubtedly send Jimin across the river never to come back to Bright Horizons again, which in all truth wouldn’t really bother him, to stop slaving away for the bourgeois, except this was his first real job, his first signed contract and a steady paycheck, and even if it weren’t for the money, he would agonize endlessly over having lost the opportunity to see you, a privilege he wouldn’t have outside of that picket fence community, and for that he would withstand all Taehyung’s yapping and twisted fantasies, no matter how sick he was of his obsession with you, whom the bastard had fallen for the same day Jimin had, that afternoon in late June when your family drove to the Horizons to pick up the keys to your new home, you sprawled barefoot over the backseat of your grand white jeep with a book in hand.

Jimin remembered that day well; he had gawped at the Patek Philippe glimmering gold on your father’s wrist, lolled outside the window as the man gestured around explaining who you were and what you were doing there, a firm, grave glare fixing Jimin over the rim of his horn-wire spectacles, and your mother sat gracious beside him with a wary mascaraed eye, your run-of-the-mill lady, identical to all the other women living in the Horizon’s white villas, with her lips painted red and a hand fan in her lacquered fingers.

For a moment, you had looked up from the book, a finger pressing into the page, eyes naked and lustrous and in that moment staring into his with an air of bright, girlish interest; and even when he had opened the gate and the jeep drove in with a powerful whir, he saw you peek through the rear glass, mouth twisting into a demure smile once you had caught his eye.

Later, when he had first sat with the richling by the river, Jimin listened to an excruciating torrent of bullshit about how you had come out to the veranda barefoot that day, in your whorish white dress, and sat with your book and an apple, crossing your legs and biting into the fruit as if you had meant to taunt him who was watching you from the window, and whom you had smiled at too once he strutted into your front lawn with a plate of his granny’s lemon pie.

“I knew I would fuck her the moment I saw her,” Taehyung had told him, speaking of this as if it were some grand catharsis, only to then cluck with laughter like a damn hen and say, “But the slut is harder than I thought.”

That was the pioneer of all the times Jimin fantasized of wrapping his fingers around the bastard’s thick, tan neck until it blued and the fucker finally croaked; the first time his hands tingled at the thought of punching him. He wanted to push his head into the river, yank his arm out of the socket, beat him bloody for the whole Horizons to see and make him eat dog shit and garbage off his own lawn. And that’s what he should have done before leaving, instead of fearing what the rich boy might do to him; then he wouldn’t have had this terrible lingering fury that made him break out a sweat every time he thought of his idiotic face.

Around midnight, when Jimin was already so pie-eyed he could scarcely follow Yoongi’s monologue, a small group of men, all with gelled hair and their shirts crisp with starch, ludicrously wandered into Jack Rabbit, buzzing with talk and decorous har-de-har, their eyes meandering over the joint and its only two patrons with an air of cool, curious solicitude. The one who had opened the door, a tall, long-faced fellow with a rounded jaw, grinned widely, black coat billowing behind him as he approached the bar.

While he sat beside Jimin, a cologne of birch tar and lavender whipping him over the face, he wished the codger a good evening, his three cohorts sidling after him while giving each other the eye.

“Hello to you too,” said the codger and plucked the cigarette from his mouth, smile so big Jimin could hardly believe his cracked lips could stretch that far. He leaned over the bar. “Been a while since I saw you here, son.”

The man spoke again, and this time Jimin was perplexed at how deep and scratchy his voice was, and still less irritating than Yoongi’s. “I was busy with work,” he had said, or something along those lines; Yoongi clicked his scrawny fingers and distracted him from eavesdropping.

“Are you even listening?” he said, and Jimin could barely make out what was his voice and what the screech of the stools.

“No,” he told him, unsure if he had heard right, too shit-faced on those rums Yoongi had made him chug to think about it too much.

“Asshole.” He grabbed his bottle by the neck; draft beer had become too warm for him, he claimed.

The group had settled at the bar but everyone aside from the cheery man squirmed on the rock-hard oak, warily taking off their shawls and coats, the stubby one seated at the end trying to hook his own on the rack. One of them, the man who seemed youngest, was typing something on his phone while glancing at the codger at intervals.

“What are the gentlemen drinking tonight?”

The man took off his coat and elbowed Jimin in the ribs; the large tag inside read “Max Mara,” beneath it a bold, flashy text: Made in Italy. “Give me a Tom Collins,” he said, and shoved his coat into the man beside so abruptly the phone nearly fell out of his hand.

Jimin scoffed. “You make cocktails, old man?”

“For you, I don’t,” he said, and Yoongi laughed with his mouth still on the bottle. The man chuckled politely too, fingers laced and propped on his elbows. His sleeves were neatly rolled up, leather wristwatch taunting Jimin with its shine. The fool held himself so high and mighty all the while he sat in the same dunghill Jimin did.

Then, and for the rest of the time spent in that hovel, Jimin watched the man out the corner of his eye, contempt sprouting furiously at his lifeless, impersonal laughter, spiraling when he opened a fat cigar case and lit one of those dark, wiener-like abominations. Pungent whirls of tobacco drifted through the small space, thick and inescapable, crashing into Jimin’s cigarette smoke. The man nudged the pack toward the codger, who begrudgingly took one and smelled it, grumbling about its staleness while he hungrily drew on it.

Jimin didn’t have to speak to him to know the type. Entitled, obtrusive, rich. The kind who were born with a silver spoon in their mouth. Former presidents of the Student Council in college, which they breezed through in a whirl of toga parties and drinking contests, always secure and unafraid because a chair at daddy’s marketing firm was being kept warm for them. Those were the sort who grew up to be glitzy businessmen oblivious to their extravagance—the cigars, tailored suits, those bland, overpriced Max Mara coats. They were all Kim Taehyung in a few years, once he buys a few blazers and decides he wants to play grown-ups.

Those pricks seemed to haunt him, follow him even to a dump like the Rabbit. What did they want of him? Why did they swat at him like flies to shit?

“That’s the problem with rich bastards,” he was telling Yoongi later, as they walked through narrow Ahyeon-dong streets with their last cigarettes in mouth, steep alleys with webbed cables, too narrow for cars. “They’re all the same. Thinking they can just walk in anywhere and be treated like kings. Fucking pricks.��� He was slurring frenziedly, tongue immobile and heavy in his mouth.

An icy breeze blew past, and all the blood surged into his cheeks, pumping, until he was so hot under the collar he thought he might go insane.

Cloud of smoke Yoongi had blown out hopped over his head and disappeared. “Stop your whining,” he said. “The world isn’t gonna stop spinning just because it hurts your feelings, Chimmy boy.”

Jimin could barely walk without vertigo and as they stumbled up the slope, then climbed the chipped rock stairs hanging onto the railing brown with rust, up till their street, he couldn’t strangle the words coming out his mouth to a halt; curses, profanities, calling Yoongi a pansy and a coward, sending him to hell, drooling like a cur, blustering with such famine and delirium until in the end he revolted himself, yet Yoongi’s apathy to the whole ordeal annoyingly persisted.

Before he went into the house, he gave Jimin a friendly slap on the cheek and told him to go to sleep, and to that Jimin stood in front of his house shouting until the man stuck out his middle finger and he was left on alone on the street and could go nowhere but his own home where, once he had closed the door, the silence was deep and thunderous.

The few hours until dawn were a painful slog. It was surreal: he wanted to fall asleep or at least do something, anything to keep the blare of quietude from piercing his ears, but instead he stared at the wall, turned over his bed like a worm, tiptoed from his room to the kitchen with his head full of nothing. He couldn’t tell what he thought about even if someone asked. Fatigue was weighing on him and the first hints of sun trespassed into the house in slits, cut up by the metal bars on the window, the sorry semi-basement rectangle. Outside of it swayed the rose shrub madam from upstairs planted; the tall brick gate it leaned on hid the street.

Jimin took a roll-up from the coffee table over his mother’s sleeping body, and it was a bad one, stale tobacco the color of hay jutting out the tip, and he sat on his bed listless, the only thing that could sedate him the thought of you. If he concentrated hard enough he could almost believe you were beside him, finger pressed into a book, window light catching onto the slight curly hairs that turreted into your scalp.

He fantasized about your skin, your big, honest eyes looking over him, the smile you gave him tonight, all those times last summer when you sat by the pool as he cleaned it, pushing a glass of lemonade into his hands, telling him it must be so hot and so hard and to come sit with you under the shade of the garden parasol for a moment. Then, as these thoughts usually went, those hands of yours, soft with all the creams smelling of pink peonies and peach, were gliding down his arm and you were thanking him for all his hard work, but he couldn’t hear you anymore because you hung on his elbow and the soft flesh of your breasts spilled over the neckline and touched his skin. He could die in that moment, if he wanted to. And although this image in particular usually led him to a cozy fairytale land, wherein he would be so muzzy and warm fighting sleep seemed tiresome—the joy of speaking with you in tongues and hands too grand to leave—tonight even those thoughts went awry.

The longer you were on his mind, the colder your smile from tonight felt, more distant, until it seemed so cruel he was certain his memory must have warped it.

What had that smile meant? Why had you said nothing to him? Would he, if he were someone like Kim Taehyung or the peacock from the bar, live to see you shun him so frigidly?

Sometime when the sun broke wholly over the sky and the rushed footsteps of the landlord’s children going to school trundled past his window, Jimin dozed off into a heavy, dreamless slumber, the stuffed ashtray beside his shoulder spilling when he rolled to the side.

The stench of cigarettes was unbearable when he awoke that noon, mother’s hands joggling him until he felt queasy. Look at what you’ve done, she was yelling, get up, get up right now, you idiot, but Jimin’s eyes felt so sunken and heavy it was a labor to open them, and he kept swatting her hands away, saying he will, saying just another moment, until she struck him so fatally on the back he jolted right up. She snatched the linen smeared with ash, singing a tired monologue of how he never listened, how she’d told him so many times not to smoke in the house, until it soared to the most common conclusion in their household: he was the same as his father. It all made his head ache and a faint taste of rum was on his tongue. Today, he felt so miserable he couldn’t find it in him to talk back to her.

At the side of the house, in the claustrophobic, dark cubicle of a bathroom, smelling of toothpaste and cleaning supplies, Jimin bent over the washbowl in unthinking ritual, scrubbing the filth off his face with soap, but no matter how many times he kneaded the bubbly foam into his cheek or spat out the gum-bloodied paste, he could not rid himself of the crud and grime anchored in his skin, as if he wore the raveled coat of a street mongrel.

Begrudgingly, he let the bathtub fill, and in the meantime sat on the fractured toilet seat that swayed to the side whenever he moved, lighting a cigarette he had swiped off the table. Now that his body had sobered, it seemed his mind followed, and in the place of last night’s ire and hurt came the routine gloom. He felt so full with nothing he thought he might implode. Everything he did last night, everything he said, even his every thought now seemed so juvenile and worthless, seemed so humiliating shame could have swallowed him whole. Why had he let any hope of you linger when all it ever did was fatigue him? He looked at the purling bathtub, the yellow rust inside it and the enamel steel chipping at the sides, and was sick with laughter. Even in a world where you wanted him, what came after that, bringing you to his house? Letting you bathe in there? See where he slept? He would rather bite his tongue off than ask that of you.

Never mind how better he wanted to make himself think he was than those banal fools swatting you, it was, in the end, a fact: he was twenty, jobless, and living with his mom in a half-basement. Of course you would shun him. Yoongi was right: he couldn’t compete with all the rich motherfuckers chasing you.

Still it was a pleasure to fantasize. As Jimin poured some little wash gel in the tub and soaked himself in the scent of camellia, the bad habit persisted, pictures of your sundress and hair tousling in the wind and all those times you touched him, where you for a moment became a creature of flesh and blood and not a figment of his imagination stalking barefoot across the lawn, sprawled furiously before his eyes, every one of them another punch in the gut.

It always was very hard for him to think of you without romanticizing you, but today all the love and worship in these dreams and memories, which had mushed together in a confused, giddy dollop, seemed cruel and masochistic to indulge in, and still he sought them and the pain they brought.

He must have enjoyed suffering if he longed for it that much.

Jimin sank his head in the water until it swallowed everything beneath his eyes, and at once, absurdly, felt entirely peaceful.

Until the water cooled and his mother began yelling for him to get out, Jimin kept punishing himself by thinking of you and holding his breath under water, and by the time he had dried himself, he was serene, almost rechristened. Nothing had changed, and he barely felt any better, but now he had accepted you were only ever meant to be in his head.

Author's Note: Hello, lovelies!! Thanks for reading all the way through to the end, I can't explain how grateful I am you took the time to consume my story! You are wonderful!

Aside from expressing my gratitude, I wanted to throw out some fun facts about this particular story for anyone who's interested. This entire written chapter had been sitting in my drafts for almost two years now, and it wasn't until a few weeks ago that I went trash-diving through my laptop and found this. At the time I'd first written this, I was very discouraged because I felt this was not good enough, and it took me many morning commutes to work to finally talk myself into posting this.

What I really wanted to gain from sharing this fic here on Tumblr, though, was an honest opinion of someone outside of my head. Is this actually any good? Is this oh-my-god-throw-it-in-the-trash bad? Is there any aspect of this I could improve? That is what I wanted to ask you. So, if there is anything at all you wish to say to me about my writing (even if that's: Uhm, you misspelled this word here, dumbass...) you are very welcome to do so!

If you're too shy or simply think this was so bad you want to forget it as soon as you scroll past this post, that's okay too! Thank you for reading and I hope you have a very nice day ahead of you.

XO, bambitae -`♡´-

#bts fanfic#bts#bts jimin#park jimin#jimin fanfic#writer#writeblr#writing#bts angst#smut#jimin smut#bts smut#bts fluff#bts imagines#fanfiction#fanfic writing#creative writing#jimin x reader#bts fic#jimin drabble#jimin scenarios

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

jimin and taehyung are only two months apart but jimin sounds like hes 12 and taehyung sounds like he’s gone through puberty twice and this is why i have trust issues

98K notes

·

View notes

Text

u think i am joking but this is genuinely how i look while writing: “god, you’re so fucking wet” and “such a good girl” for the hundreth time in my miserable existence

23K notes

·

View notes

Text

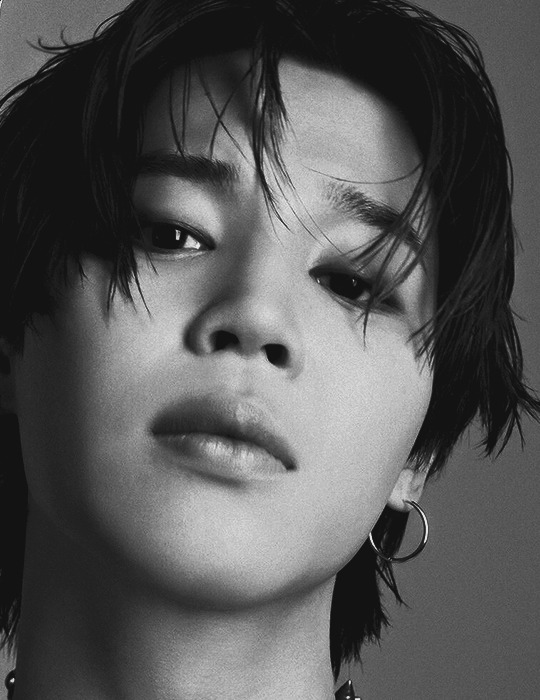

230305 - jimin on instagram

814 notes

·

View notes

Text

JIMIN

LOVE YOURSELF 承 ‘Her’ Jacket shooting sketch.

383 notes

·

View notes

Photo

jimin for w korea

9K notes

·

View notes