Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

New website

Hello, I’ve a new website. I’ll be updating things over there from now on, less so here. https://www.andrebagoo.com/

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Thanks to Opal Palmer Adisa for this interview which was published in the Jamaica Observer of February 10, 2019.

OPA: For me, the history of Trinidad and Tobago is synonymous with Pitch Lake as that was one of the first facts I learned and because it also saved Columbus and allowed him to continue his colonial voyage. So what is the meaning and implications of this title for your collection?

AB: With Pitch Lake I was drawn to several things. Firstly, the polyvalence of each word. Pitch, a quality of sound, a measurement of steepness or highness, a degree of intensity, a space for play, an act of service in a game, a proposal, the density of words on a page and, of course, especially in Trinidad, another word for asphalt, bitumen, tar. Lake, a place within a terrain, a space filled with water, a metaphor. The conflation of these dynamic words pleases. They resonate in a potentially bottomless kind of way.

And of course the layers of geography, myth, history. The Pitch Lake is itself the world’s largest asphalt lake. Its history is not limited to Columbus, the indigenous peoples of this land developed myths about its formation and purpose long before him. (Incidentally, it seems there is some uncertainty as to whether it was Columbus or Sir Walter Ralegh who encountered the lake first). The lake itself is a natural wonder, its level has barely changed over the centuries. Ancient fossils and objects are spit out of its depths every day. It is a link to the past and the future. Scientists have said there are organisms in it that might give us clues as to what life on moons might be like.

Meaning and implications? That’s really not for me to say. All I can offer is that I was drawn to the lake as a symbol. I hope the whole book asks questions about language, the environment, sexuality, politics, the post-colonial condition. Asphalt from the Pitch Lake has reportedly been used to pave roads and runways all over the world including at Buckingham Palace and La Guardia Airport in New York. So too I hope my words travel.

In addition to the actual lake, Alfred Mendes’s 1934 novel Pitch Lake was also a presence. There is a bit of intertextuality. So there are lots of layers for me. Which I find interesting. Which says something about me and my sad life. Ha.

OPA: Some of your work is definitely a talking back to certain Caribbean iconic markers, such as “Sargassum,” and others seem a mirror trying to break beneath skin and thought such as “Poui.” How do you attend to your craft, the development and debut of a poem?

AB: Each poem is its own thing, and it's not often easy to predict where or how the idea is going to find expression. The most thrilling part of writing is the preparation to write, yes, but also the moment when you throw everything out the window and just let things happen to you and your poem. ‘Sargassum’ references the sudden proliferation of that seaweed in recent years due to climate change, but of course, it’s also alluding to a history which reaches well beyond the Jean Rhys novel. I see ‘Poui’ as a kind of aubade.

OPA: As poets, we sometimes write about our life or use it as a point of departure. There are hints of autobiography in some of your poems, but they feel more like pieces of a puzzle, the whole of which we will never get, or private revelations that is really a mask for something else, for example, “The Lost Earrings.”

AB: The closing section of the book is a series of poems which I regard as small thought experiments, playing with the idea of narrative, interrupting linear notions of time, allowing a stream of consciousness to be dammed then released then remixed then reversed—each a curation of complex emotions. I’m always interested in what the reader finds and their journey.

As for autobiography and masking, think of it this way: a poem is a Carnival costume. It might have a lot of fabric and fancy trimmings. Or it might be slender and revealing. Always, we get a sense of the human body beneath. Always, the choice of mask reveals something about the wearer of the costume. Paradoxically, it’s when we deploy masks that we show more of ourselves.

OPA: As a gay man living in the Caribbean, specifically Trinidad, where homophobia was, and perhaps still remains an issue, how have you addressed that topic in your writing? And now that the buggery law has been struck down, and Trinidad had its first Pride celebration, do you feel safer as a gay man to express that topic more openly in your work as in the poem “After Andil Gosine”?

I don’t ever want to feel safe in my writing. I think the question of ��openness” has a lot to do with expectations. Do we expect certain poets from certain backgrounds to always write poems about certain topics? When they defy us with poetry which is not overtly lined to any specific agenda does that make us inclined to regard them as hiding behind masks? Would we hold up heteronormative society to such standards? Are only certain types of poets allowed to deploy the fullest range of artistic expression and experimentation?

The ruling on the buggery law and our first Pride parade were touchstone moments which inspire hope. But the problem of homophobia in our society is a long-term problem.

I don’t address issues in my writing. I just write. And I let whatever comes to the surface rise. Hopefully, this brings me closer to a truth and that truth allows me to bridge different worlds, including worlds of diverse sexualities.

For me, the question of how open you get in your work is more about experience than a wider social narrative, though they undoubtedly blur. It’s like asking would you like to be the subject of a reality TV show or not? Each person has a different answer depending on their personality.

Some of my sexiest poems, or poems in which queerness is part of the fabric of the poem were written and published (and performed) years before recent developments.

That said, every poem, no matter how clothed, is a deeply personal artifact. Take it or leave it. And poetry is a freedom that I am entitled to. Feeling free in real life does enable me, somewhat, to be braver in whatever I write. And, yes, who knows what a sense of freedom might bring to the mix.

OPA: I really enjoyed the “Art Teacher,” which seems strictly a prose piece, so I am curious about its inclusion in this collection?

It comes in the LAKE section, where I examine language itself, the idea of words forming an endless sea of (broken) narrative. The juxtaposition of a conventional linear narrative alongside the other pieces is meant to trigger comparison; to create the sensation of something suddenly out of place, complicating and interrupting the three-section schematic of the book. Part of me wanted to ask the question: what’s the distinction between prose and poetry? Why is a story not a poem? Heidegger says poetry is the essence of all other art forms.

OPA: Do you have any urge to write strictly prose, where the story element takes precedence?

AB: Poems tell stories. Stories can be poetry. Dylan Thomas. Borges. Baudelaire. All wrote both. That said, I do have those urges. I have lots of urges. Don’t we all? It depends on the pressure giving birth to a particular idea. It’s a matter of feeling things out. There are times when I have written the poem, then the story, then done the painting.

You can read the full interview here.

#Pitch Lake#Poetry#Caribbean#LGBTQ#Gay#Caribbean Literature#Literature#Poems#Jamaica#Observer#Interview#Poets

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A recording of my poem ‘The Tourist’ is featured in episode 2 of ChapelFM’s overview of Caribbean poetry selected by Juleus Ghunta. Starts at 08:25. Listen here.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

For World Poetry Day 2019, I was asked by Dazed to say what political poetry means to me. Here’s what I said. (Photo Marlon James.)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Was surprised by a hard copy of this the other day and even Chaplin is like whaaaaat? There’s something about holding magazines in your hands, the ink the glossiness. Thanks Breanne Mc Ivor and Maco People for this feature! 😍

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

SOMETHING about the planes. They draw him in. Perhaps it’s the drama, the epic struggle of the airmen fighting to get their machines off the ground. It gives him hope when it comes to his writing. Yet, leave the excitement of this air show in 1909 behind and fast forward to his deathbed decades later, in 1924, when he is editing ‘The Hunger Artist’. The joy of ‘The Aeroplanes at Brescia’ is gone. Instead, Franz Kafka gives us the story of a man nobody believes, a man unable to escape suspicion no matter his sincerity, a hero grounded and made subject to the merciless, never-ending gaze of onlookers, who dies miserably in a cage. The metamorphosis is complete.

What happened to him? The mysterious menace that pervades Kafka’s work clouds our understanding of his life. We are tempted to believe he was miserable, dying at the relatively young age of 40. He starves to death. He has a form of tuberculosis that seals his throat. His three sisters Ellie, Valli, and Ottla are murdered during the Holocaust by the Nazis. Had he survived he too might have met the gas chamber.

But just as his novels are left incomplete, so too Kafka’s life story. More manuscripts, more diaries, more pieces of correspondence are destined to emerge. For decades they have been subject to a legal battle, scattered in bank vaults and safes in Israel and Switzerland thanks to Max Brod’s secretary Esther Hoffe. Yet, even if Kafka the man is yet to fully come out, some readers can already sense what town knows. Here is a writer deeply concerned with the oppressive power of the deep state; who fears autocrats as much as he fears fathers; who exudes queer sexual desire but must hide it. This is the world in which Anu Lakhan’s new chapbook Letters to K, complete with drawings by Kevin Bhall, arrives.

— from 'Reading Kafka in Port of Spain', my review of Anu Lakhan's Letters to K.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

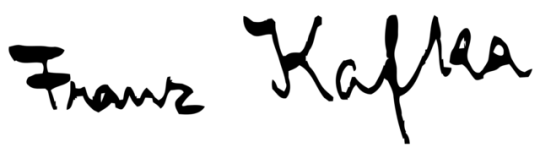

On the first night of the Kings and Queens of Carnival competition at the Queen’s Park Savannah, Vaughan crosses the stage. He’s plucked a single line from the novel and built a costume around it. “The Sun Rises and Overwhelms the Sinnerman” is a coruscating metaphor prancing to Nina Simone’s “Sinnerman.” Like a blinged-out version of Peter Doig’s 2007 painting “Man Dressed As Bat”, Vaughan is gorgeous, radiant, yet gloriously ambiguous as he looks down on us, a giant studded moth with eyes lined with red. Your blood flows faster.

Moko jumbies might look to the past, but this band’s inhabiting of Harris’ novel opens up fresh possibilities. It’s a perfect marriage between one imaginative world and another; a kind of meta-fiction or cosplay in the extreme. And what a procession it all amounts to!

— thanks Global Voices for asking me to write about Moko Sõmõkow’s Palace of the Peacock in this feature published exactly one year after the death of the great Guyanese poet and novelist Wilson Harris.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Palace on stilts

“A brilliant day. The sun smote me as I descended the steps. We walked to the curious high swinging gate like a waving symbol and a warning taller than a hanging man whose toes almost touched the ground; the gate was as curious and arresting as the prison house we had left above and behind, standing on the tallest stilts in the world.” (The Palace of the Peacock, p. 21)

Everywhere in The Palace of the Peacock, we are asked to look up. At the sky, at the sun, at swinging gates, at trees, birds, waterfalls, stars, comets, at dangling nooses, up ladders, and even at houses built on stilts.

Why a novel? Why bring a mas based on a book? And a book by an author with a style as dense and formidable as Wilson Harris? Why? Because this is a book that teaches us to levitate. Consider its scenes of elevation, literal and spiritual, as embodied by the quotation above. But as is typical of Wilson Harris nothing is one thing or another. What is dead is also alive; what is up is also down:

“The whispering trees spin their leaves to a sudden fall wherein the ground seemed to grow lighter in my mind and to move to meet them in the air.” (28)

“Every boundary line is a myth,” (22) the character called Donne warns. We are in the landscape of the mind, a “chaos of sensation” (24), a collage, a mosaic, a painting. We are journeying through a “masquerade of appearances” (13), the expanse of the fabric of the universe.

Reading The Palace of the Peacock is, therefore, like encountering a riptide. You have to cut your way through it diagonally or else you drown.

This is not prose. This is a book-length poem that stretches its language; a rich stew in which the twins of past and present are blurred, as the Mayans might blur them. People appear, each a “character-mask” (8), each both dead and alive, dreaming and awake, traveling yet not moving, dancing yet still, doing things, finding things, yet not finding.

Slowly, the novel reveals its secret: the person who is at the center of it all, that person emerges—like the star-studded peacock that gives the book its title—at the very end, making it plain that we have been reading a self-portrait in the form of a written mas.

Here is a book that challenges the idea of the novel, turning it into a poem, a painting, a dance on stilts, a history lesson, a Carnival of the soul. It seeks now, through this band of Mokos, an audience.

— from my talk given at the launch of ‘The Palace of the Peacock’, this year’s Carnival band by Moko Sõmõkow, at Granderson Lab, Belmont, February 14, 2019.

#WilsonHarris#MokoSomokow#Moko#Novel#Poem#Caribbean#Guayana#literature#trinidad#Trinidad and Tobago poetry

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Chaplin appreciates a room with a view.

4 notes

·

View notes

Quote

I wanted vast complexity relegated to a small screen in a small corner, mirroring how queer sexuality in TT is often suppressed and gazed at furtively in discrete recesses. Hughes, who visited Trinidad and had ties to this country, is the perfect symbol of how queerness is dismissed and etherised by straight power.

from Janelle De Souza’s Sunday Newsday report on my collaboration with Adam Patterson on Langston Hughes

1 note

·

View note

Text

A note on ‘Sailors’ with Adam Patterson

SAILOR MAS takes distinct form in the Caribbean, but really the sailor is a universal symbol. A sailor is someone who crosses water. Before he was a poet, Langston Hughes was a sailor who explored.

We were both inspired by Hughes. We discussed sexuality’s mediation through a sea of oblique encounters - be it in books, on screens, through spyglasses. For me, making a film poem fit. I wanted vast complexity relegated to a small screen in a small corner, mirroring how queer sexuality in Trinidad and Tobago is often suppressed and gazed at furtively in discrete recesses. Hughes, who visited Trinidad and had ties to this country, is the perfect symbol of how queerness is dismissed and etherised by straight power.

Also, I wanted to suggest we should think of poetic form more widely. Just as poetry works through what is withheld, so does it gain by what is absorbed. All art is poetry, Heidegger said. And performance need not be a grand gesture. In fact, it’s the supposedly smaller everyday performance via laptop screens or in quiet corners that matter. As the opening line of my poem suggests, Hughes was a performer all his life.

Finally, it felt right on the night of the event last Sunday at Alice Yard to have proximity to Adam’s stationary maypole, a reference to the Barbados landship tradition. For me, this proximity came to embody the idea of dance through negation; of impulses that could be acted upon left dangling; of horizons yet to be explored.

Read more here.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

'All art is poetry’

Thank you to Paul Brookes who asked me to be a part of The Wombwell Rainbow interview series. The full interview is reproduced below.

Paul Brookes: What inspired you to write poetry?

In my teens, I wrote poems for boys. I made little chapbooks and would gift them to these baffled studs, sometimes anonymously. Poetry became me.

PB: Who introduced you to poetry?

The answer to this question depends on the answer to another question: what is poetry? I feel poetry is around us all the time even when it’s not on our radar. So it’s hard to say who introduced poetry to me. But I do remember a teacher who showed me a whole new level of analysis when it came to reading poetry. This was in secondary school. We had Mr Perkins for English. One hot afternoon he came in and told us to open our textbooks and read ‘Mass Man’ by Derek Walcott. He unpacked the poem word by word, line by line in a way that felt like discovering the world is not flat. I went deeper. I explored the National Library’s collection. I found poets like Samuel Beckett. (I encountered his poetry before his plays, which was a blessing.) The poem became not only an object but also a process. All at once so much opened.

PB: How aware were you of the dominating presence of older poets?

As a reader first and foremost, other poets, other voices, always dominate. Very early on, encountering each poet’s work was like encountering strokes of a painting, shapes of a costume, notes in a score: the form always seemed magical and meaningful. Dominating was not the word. It felt like communing. It still feels that way.

PB: What is your daily writing routine?

Someone once advised me to always listen and wait for the poem. To give it time. To let it happen. So I would say it depends on what you mean by writing. The preparation for writing – researching things, feeling things out – is as much a part of writing as typing words or making jottings in a notebook. Sometimes I latch onto a form or rhythm that works. In those instances, I might devise a routine to support the work. Other times I am haphazard. So I guess if there is a routine it is the absence of routine. Opening a space for mystery, accident, surprise.

PB: What motivates you to write?

Dancers have this thing called muscle memory. Writing feels like something that happens to me because it’s now part and parcel of me. Even when I step away, even when I cross into other terrains like dance and visual art, it remains. Heidegger believed poetry was the essence of all art and sometimes I think that’s true. In a way, then, everything motives me.

PB: What is your work ethic?

One of my favorite books is What Work Is by Phillip Levine. Something about its searching, its reportage, its drilling down and surrender to the profound questions that surround human beings and our labours beguiles me even in its uncomfortable moments. It all seems to implicitly ask: What is the work of the poet? Someone once said every poem is an ars poetica. I feel each poem makes a world while also becoming a part of it; is a setting-into-being that opens setting-into-being to new possibilities. So, to go back to your question, I guess we can look at this in terms of what work the poem does, what work the poet does, and whether there is a relationship between both things, or a separation, and what patterns or systems might shape how much I do any of these things. I am tempted to say I have a strong work ethic driven by the fact that I’m not sure how much time I have on this planet. At the same time, Locke’s insights on labour and mercantile notions of productivity don’t seem to be useful models when approaching poetry. All I can say, then, is these things called poems come, sometimes frequently sometimes infrequently. Always there is a questioning: is this a poem? Why? Why not? At which stage is the poem a poem? When someone else reads it? When I write it? When it forms, inchoate, in my body? Do I have a responsibility or relationship to it? And do only poets write poems? It’s hard to paper over all of this and describe my own processes. Even if I dream of a world where poems, which seem to do nothing, change everything.

PB: How do the writers you read when you were young influence you today?

I like to read in an engaged way. I’m experiencing what I am reading. I am also analysing what I am reading. And learning from what I am reading. So whatever I read tends to soak in. I’m very permeable that way. I am not too sure how to trace the strands of influence but it’s there. But influence is more than just a surface resemblance. It’s about process and context; particularly civic context too. Real influence might not be discernible on the page.

PB: Which writers do you admire the most and why?

Currently, I’m drawn to Heathcote Williams’ audacious investigative poetry; as well as Tom Raworth’s work. Raworth was one of the first people to have open heart surgery and someone once suggested you could sense a different kind of heartbeat pulsing through his writing, an idea I find not only beautiful but true when considering the sensibility of some of his poems.

PB: Tell me about the writing projects you have on at the moment.

In 2018 I published The City of Dreadful Night, a book-length visual poem that takes James Thomson’s poem of the same name and seeks to dialogue with it through a sequence of images. I like to think of form in poetry in a wide sense, extending beyond questions of whether a poem is a sonnet or a villanelle to include questions of medium. I’m drawn to this idea of drilling down to the essence of things using whatever is at hand. To go back to Heidegger, perhaps what he said was true, “All art is poetry”.

- from The Wombwell Rainbow.

#interview#poetry#thewombwellrainbow#Caribbean#heidegger#stella artois#pitch lake#The City of Dreadful Night

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Yes it happened right here, a spot of blood appeared and grew.

— from ‘Scarlet Ibis Variations’, my visual poem sequence published at Burning House Press https://burninghousepress.com/…/andre-bagoo-scarlet-ibis-v…/

Thank you Paul Hawkins for selecting this piece to round off your guest editorship. Around this time last year, some of the first ibis works (heavily influenced by Broodthaers/Mallarme) were published by SJ Fowler over 3AM. Since then, sections were published in The Poetry Review, performed at Fowler’s Poem Brut and Tony Frazer’s Shearsman readings in London, turned into film poems by Soraya Moolchan and Israel Ramjohn (screened at The Poetry Society) and me (screened at the IMAX opening night of Green Screen 2018), and also made an appearance in Wretched Strangers, edited by Ágnes Lehóczky and JT Welch. To think of the germ of this idea starting with Ovid all those years ago. Onward voyagers & happy new year 2019! Xo

(O & apologies to Henri Michaux)

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

He had these poems within him; he rearranged his life in such a way to match the poems inside him longing to come out. — talking to Breanne Mc Ivor about Robert Lax, the writing life, my latest book and more in Maco People https://macopeople.com/people/andre-bagoo-for-the-love-of-language/ PHOTO BY BREANNE MC IVOR. (at Queen's Park Savannah)

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Being your slave, what should I do but tend Upon the hours and times of your desire? – Shakespeare, Sonnet 57 My sonnet crown, 'I was programmed into thinking I could be a poet', appears in NO, ROBOT, NO! a book all about robots, AI, and things that go too far. Beautifully compiled designed and edited by Jon Stone and Kirsten Irving. Chaplin can’t get enough of it. #asemic #poembrut #poetry #robotics @sidekickbooks #norobotno #literature #sonnet #shakespeare #sonnetcrown https://www.instagram.com/p/BqUvtwjgi8j/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=22vyu2x1jq55

1 note

·

View note

Photo

‘now the black, the cut, the red the colony dispersed by bullets I ask whose land it is’ Just in time for Republic Day 🇹🇹, my poem — ‘The Scarlet Ibis is the National Bird of Trinidad & Tobago’ — is published in WRETCHED STRANGERS, an act of solidarity; an anthology crossing borders during the time of Brexit and whose proceeds will be donated to charities fighting for the rights of refugees. My contributor’s copy arrived in the mail last week like the monolith from Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, traveling through space and, perhaps, transporting us to some moment when all that will matter is not what matters now, when we will truly unite. More: https://www.instagram.com/boilerhousepress/ #books #bookstagram #bookshelf #bookshelves #bookstagrammer #bookshelfdecor #books📚 #bookstoread #booksbooksbooks #bookstore #bookshops #bookshop #bookstores #bookseries #bookstgram #booksigning #booksamillion #bookselfie #bookseller #booksnotforsale #bookstack #booksonbooks #bookslover #bookslut #bookshopping #bookstagramer @jtwelsch (at Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago) https://www.instagram.com/p/BoEeG1NHgM9/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=17nxa45qsaku8

#books#bookstagram#bookshelf#bookshelves#bookstagrammer#bookshelfdecor#books📚#bookstoread#booksbooksbooks#bookstore#bookshops#bookshop#bookstores#bookseries#bookstgram#booksigning#booksamillion#bookselfie#bookseller#booksnotforsale#bookstack#booksonbooks#bookslover#bookslut#bookshopping#bookstagramer

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

It was a pleasure appearing on the LMC’s podcast last week discussing 🏳️🌈 in TT. Listen https://latinomediacollective.com/2018/09/14/sept-14th-2018-lgbtq-victory-in-trinidad-tobago/ Photo: The Silver Lining Foundation. #GlobalVoices #BeyondLatinx (at Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago) https://www.instagram.com/p/BnylNvyn1Uj/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=1rwt4l4v02u9l

5 notes

·

View notes