Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

A further step with Anglish

Folk like Anglish for it doesn't brook the borrowed words, for it is a lutterer English. But there's something that unformithely comes along when swaping out ellandish words with those from the same tongue kinfolk: foroldness.

And this seems to be something Anglish-followers like, for I found an almost fulwrought foroldening of English staffcraft. And I'm not going to hide that I'm one of those who like foroldening, and that I liked to know about this deeper back-to-the-roots.

I'll be talking about was changed in this forolder Anglish here. I'll be reckoning the links to a more throughgone writ in the end of this writing.

Staffrow (Alphabet)

Only two bookstaffs are eked: Ƿƿ (/w/) and Þþ (/θ/, /ð/). Yes, it's not that gripping, but things truly get started with the switches!

⟨c⟩ as /s/ > s (cinder > sinder)

⟨ch⟩ & ⟨tch⟩ as /tʃ/ > c/ce (chin > cin/choke > ceoke)

⟨dge⟩ as /dʒ/ > dg (bridge >A curious mind is a terrible curse bridg)

⟨gh⟩ as yoreloreish [x~ɣ] > g (high > hig/night > nigt)

⟨ie⟩ as /i/ > ee (field > feeld)

⟨le⟩ as /əl/ > el (neetle > neetel)

⟨o⟩ as /ʌ/ > u (son > sun/some > sum)

⟨ou⟩ & ⟨ow⟩ as /aʊ/ > u/ue/uCe (hound > hund/sow > sue/loud > lude)

⟨ough⟩ as /aʊ/ & /ʌf/ > uge (plough > pluge/tough > tuge)

⟨qu⟩ as /kw/ > cƿ (queen > cƿeen)

⟨sc⟩ as /sk/ > sk (score > skore)

⟨sh⟩ as /ʃ/ > sc (ship > scip)

⟨th⟩ as /θ/ or /ð/ > þ (the > þe)

⟨u⟩ as yoreloreish /ju/ > eƿ (hue > heƿ)

⟨u⟩ as /ɜ/ > e/i (bury > berry/burden > berden)

v as /v/ > f (leave > leaf/over > ofer)

w > ƿ (water > ƿater)

⟨wh⟩ as yoreloreish /hw/ > hƿ (whelp hƿelp)

y as /j/ > g/ge (yes > ges/yore > geore)

⟨z⟩ as /z/ > s (graze > grase/fizzy > fisy)

Retchings for why it was switched to that in the link reckoning below.

Can you already see the forolderlooking from this? Here's a wordset I'll be brooking as forebisen:

Unforolded: The tough errand to dodge through the crowded boughs of a fern oak tree thared skill and lastingness. Forolded: Þe tuge errand to dodg þruge þe crueded buges of an fern oak tree þared skill and lastingness.

That truly pleases me and is aslaking seeing English truly looking like a Germanish tongue. I thought about writing in a more and more forolded way as I reckon the changes, but, for the sake of a flowsome reading for the reader, I'll leave this list aside, but, if you'd like to read wordsets looking as such, there are sere in the from leaf at the end of this upload.

This switching might be enough for some, but there are those, like me, who would like to go even further and see, too, a forolded speechcraft.

Theedness and some throughnesses (Conjugations and some details)

Before we get started with theedness, we understandendly will be brooking the forename "thou". A forolded theedness may be known for all, since it can be outlined through the twoth and the third atell:

Twoth: anward > -est; forthwitten > -edst

Third: anward > -eth

And that's all, hence you can make any wordset:

"The man giveth the boy a book"

"A woman walketh through the woods"

Underyet: there are some sunderly shapes: doth (does, spoke /dʌθ/), hath (has), saith (says, spoke /sɛθ/).

Asking

To make asks, we will leave out the ask markers "do" and "does". Instead, we'll put the tideword in the beginning of the wordset, as one does in Deutsch:

Does he know the answer? > Knoweth he the answer?

Where do you live? > Where livest thou?

Ofolder and chirten.

Naying

Also in naying wordsets "do" and "does" swind. Instead, we use "not" after the main tideword:

I know not.

He came not.

With wrayingly, the ea is putting "not" after a wrayingly forename, but before a meanname:

I love him not.

I have not the book.

If the wordset has a underwordset, "not" will be right before the latter:

The king thought not that he was in any danger.

Byings and kins (Declinations and genders)

Here is the knottiest thing to learn, though not the hardest - you'll only need some time. Byings and kins are a widegale ken, which, for me at least, is the most gripping thing in speechcraft, for it's where the tongue shapechanges the most.

The first thing we need to know is that English wonted to have kins: werely, wifely and neither. And byings: nemmeningly, wrayingly, streeningly and forgivendly. And it turns out not only the meannames, but also the beckoningly forenames, lithwords and ekends had their own kin and bying bendings. Although Anglish doesn't brook the forgivendly bying.

Unheeding the thoughts of how these bendings would have grew and going right to the retching way English would look like today, we have:

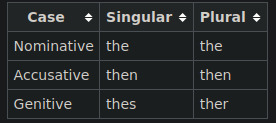

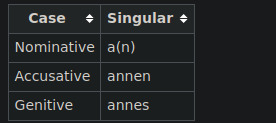

Markoff lithword

Unmarkoff lithword

Ekends

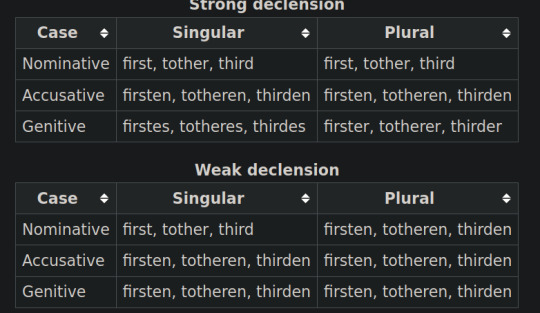

But ekends are not that ofold though. It's said the strong-weak shed would have likely been kept. So ekends can be either strong or weak, and their bending changes for it. Although we can overlook the weak one and brook the strong one only, I'll be brooking both for the sake of a rawer forolding.

On the other hand, the ea to bend it is easy: weak ekends are those whose meanname is with a lithword, kithing forename or it's in streeningly; strong ekends are those that are unmarkoff. Here is the bending:

With these changes, let us take a look at what our bisen wordset looks like now:

Unforolded: The tough errand to dodge through the crowded boughs of a fern oak tree thared skill and lastingness.

Forolded: Þe tuge errand to dodg þruge þe cruededen bugen annes fernes oakes trees þared skill and lastingness.

Dealnimmends (Participles)

Dealnimmends are like the ekends, and as such they would be bended with the same endings, if there were not an unbiseniness in them:

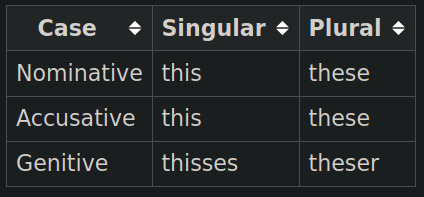

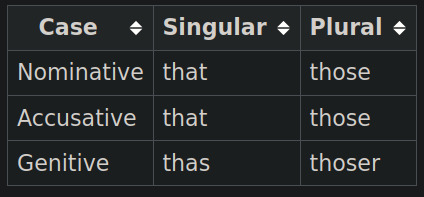

Kithings (Demonstratives)

The kithings, since they are also ekendish, also are bent:

Rimes (Numbers)

Believe it or not, rimes wonted to be bent in the past. The rimes "one, for some ground, were the only ones that are bent. Rimes are either mainly or endbirdly. And, since they can be brooked with lithword, they can also be either strong or weak. The mainly's benting is:

The endbirdly's benting is:

Ownerly forenames (Personal pronouns)

And going even further, we forolden the ownerly forenames:

The shapes "mine" is now brooked before words beginning with a clepend as "a(n)". The same for "thou", which becomes "thine".

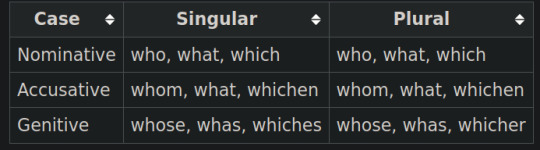

Askinglies

And, alongside with it, the askinglies are also bent!

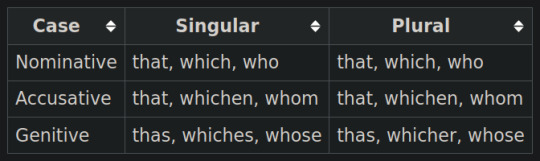

Kinshiply (Relatives)

Forget we not the kinshiplies:

And since "that" and "which" have now a streeningly bying, there's no more anyet in brooking "whose" for unmanly words, so:

Þe dog hƿose oƿner is far aƿay > Þe dog þas oƿner is far aƿay In þe ƿoods þere ƿas a birdling, hƿose huse was red > In þe ƿoods þere ƿas a birdling, hƿices huse was red.

---

There are still other changes that make it even more forolded, reliving raw shafts of the tongue, but I think this is enough for now. It's not like you would be wrong brooking only a stitch of the forolding anyway, since it's clearly underfangendly to not fully forolden. I shall likely make another upload on these foroldenings in the toward.

---

Froms:

Staffrow: https://anglisc.miraheze.org/wiki/Anglish_Alphabet

Theedness: https://anglisc.miraheze.org/wiki/Archaic_grammar

Byings and kins: https://anglisc.miraheze.org/wiki/Archaic_case_%26_gender

4 notes

·

View notes