Text

Excerpt from an Interview Transcript

DAVID GERGEN: And what you're arguing is that that tradition has passed down in the black community from one generation to the next, but it also, what struck me about your book was, as opposed to the usual suspects we find as causes of crime or homicide, say poverty, economic issues, lack of jobs, drugs, what have you, you really--I was surprised to the degree to which you felt that the tradition of violence was passed down from father to son, father to son.

FOX BUTTERFIELD: Yes. And this was a big surprise for me. Willie, when he was a young boy,he didn't know exactly what his father had done, and his mother tried to shield him from the terrible secret that his father killed two men. But one day he saw on his grandmother's dresser a picture of a man in prison uniform. And he asked who it was, and his grandmother said, "That's your father. He killed two men. He's in prison. And when you grow up, you're going to be just like him." And Willie took that in a way as a mark of, of honor, of status, that his father had committed this worst of all crimes.

DAVID GERGEN: It sort of made you the baddest man on the street.

FOX BUTTERFIELD: It made you the baddest man on the street, and so he went around telling his teachers and his playmates, he said, "Don't mess with me. My father was a killer, and when I grow up, I'm going to be just like him."

DAVID GERGEN: But it was one of the only things he had to hang on to.

FOX BUTTERFIELD: It was. It created his identity, and interestingly, the same thing had happened with his father before him. His father early on knew that his own father was a, was acriminal, and tried to model himself on that. I think we all know that if your father is a doctor orlawyer or fireman or policeman, you're likely to go into their line of work. What doesn't occur tous, because we haven't had that experience, is if your father is locked up in prison, you may, you find that a powerful, if perverse, attraction.

DAVID GERGEN: So how many people would you say there are in prison today who have--related to others who have been--and their family who have been in prison?

FOX BUTTERFIELD: It's an incredible number. Among, among juveniles who are locked up, it'sabout 50 percent of all kids nationwide who are locked up who have fathers or other close relatives who've been in prison.

DAVID GERGEN: And they in some ways have idolized them and then tried to follow them.

FOX BUTTERFIELD: And they have taken this as some kind of a model.

Butterfield, Fox. "Deadly Legacy." Interview by David Gergen. Pbs.org. Pbs, n.d. Web. 16 May 2013. <http://www.pbs.org/newshour/gergen/butterfield.html>.

1 note

·

View note

Link

A clip from an interview with Fox Butterfield

0 notes

Text

Politics and Punishment

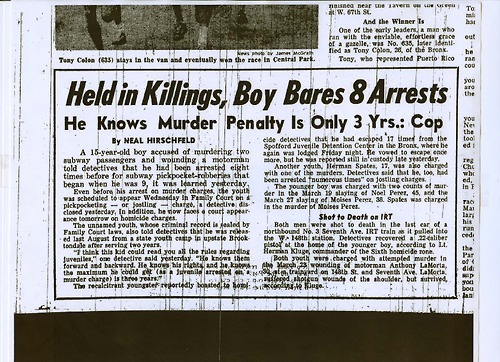

Governor Hugh Carey

In 1978 fifteen-year-old Willie Bosket was sentenced to only five years after he murdered two men on the subway. His sentencing sparked a public outcry and in response to this the Juvenile Offender Act of 1978 was put into place. This act made it legal for individuals as young as thirteen years old to be charged as adults for murder in New York State. An article written by Katherine Ramsland clearly illustrates the relationship between politics and punishment. At this time and immediately following Willie’s sentencing, Governor Hugh Carey was working on his campaign. His Republican opponent fought against Carey by stating that he was too soft on crime. The opponent followed this by proposing a harsh new law that would allow for minors to be charged as adults. After this incident and reading a newspaper article that disclosed leaked information about the Willie Bosket case, Carey decided to take immediate action and the Juvenile Offender Act was passed. Ramsland states, “this law reversed the tradition of the past 150 years that children were malleable and could be rehabilitated and saved. There was now an attitude that there were truly bad kids and they should be locked away from society. It was too late for Willie to be tried under this law, but it certainly changed things for others his age.” Meaning that this law marked a drastic change in history. This caused society to change its view on the innocence of children and how they were to be dealt with in the future for malicious crimes.

Ramsland, Katherine. "The State's Outrage." Willie Bosket — — Crime Library on TruTV.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 May 2013.

0 notes

Text

Willie and differential association theory

From the age of 6, Willie Bosket began showing signs of deviant behavior with small acts such as grabbing a woman’s pocketbook or stealing a woman’s wig. Willie showed signs of anti-social behavior. He didn’t like to play with the other boys in the neighborhood. He disliked sports and showed distaste for teamwork. Willie was satisfied being alone. Willie began showing signs of violent behavior when he jumped at a stranger and grabbed his neck. Willie wasn’t even in school yet when he began this streak of violent behavior. His mother said Willie’s environment is what influenced his actions. Willie took pride in the status he had created for himself. His dream was to be the best amongst his peers. Just like Butch in August, he thought his violence was a reflection on how he is respected.

“Laura blamed the neighborhood. She believed she had been a good mother - she worked hard, she saw that her children had a roof over their heads, food to eat, and clothes to wear. But Harlem had deteriorated since she was a girl, she reckoned - lots more drugs and crime and guns. “There was people out there doing thing, and Willie thought he could do the same thing he saw them doing,” Laura said.” (p. 139)

“Coming up in that neighborhood, Willie had learned the code of the street at a very young age, just as his father had in Augusta – that the secret to survival was a willingness to use violence, to be always ready to fight. But Willie was much smarter than the other kids on his block, and also more driven, more highly motivated. He wanted to be the best. So he took the code of the street to the extreme – he would be the most violent. It would be his ticket; it was the only way Willie knew to get ahead” (p.140)

0 notes

Text

Butch and differential association theory

Butch, growing up as “the orphan of Ninth Street”, began showing signs of trouble at a young age. He soon began a life of crime for numerous violent acts. When at Rockland, doctors examined Butch. Two-thirds of the boys at the reformatories had a father with a criminal record. Amongst those boys, 40% had a grandfather with a criminal record. Butch idolized his father for his criminal past. There are other explanations for his violent behavior. Butch’s environment played a role in how he acted. His life on the streets proved to give him more lessons than school. His peers acted in violent ways and he became developing his own values on life.

“One reason for this striking continuity might be that the boys, like Butch, dreamed of copying their fathers. Or perhaps the fathers and children in these criminal families shared an underlying vulnerability, like impulsiveness, that predisposed them to antisocial lives if they grew up in a certain environment. Impulsiveness is a trait of temperament, and such traits are to some degree inheritable. Pud, James, and Butch were all impulsive” (p. 103)

0 notes

Text

James and differential association theory

In All God’s Children, the differential association theory can be used to explain the criminal behaviors of the Bosket men. The Bosket men wanted people to be intimidated by them. Each Bosket man learned from their surroundings through direct observations from their peers and family members. This line of criminal behavior carried on through the Bosket men. Willie’s grandfather, James, grew up without a father figure in his life. He grew up learning about his father and wanting to emulate him. He wanted people to fear him because it made him feel powerful. This shows the differential association theory because although James had never met his father, learning about his actions led to James to pursue his very own “dream” of being like him.

“It was an all-American story, with a twist. Americans take pride that if they are doctors or lawyers, farmers or policemen, their sons will follow in their footsteps. James was pursuing the old dream. It was just that his father had beaten and robbed people. He told his relatives, “When I grow up, I’m going to be a bad man, just like my father.” (Butterfield, 1995, p.75)

Butterfield, Fox. All God's Children: The Bosket Family and the American Tradition of Violence. New York: Knopf, 1995. Print.

0 notes

Text

Differential Association Theory

Edwin H. Sutherland

The differential association theory is a view that holds that individuals engage in criminal activity when they believe the rewards of that activity outweigh the rewards of normal and legal activity.

According to Edwin H. Sutherland and Donald Cressey there is a set of principles that accompany the differential association theory.

The principles in Sutherland and Cressey’s theory that pertain to All God’s Children are:

Criminal behavior is learned

Criminal behavior is learned as a by-product of interacting with others

Learning criminal behavior occurs within intimate social groups

Learning criminal behavior involves assimilating the techniques of committing crime, including motives, drives, rationalizations, and attitudes

The specific direction of motives and drives is learned from perceptions of various aspects of the legal code as favorable and unfavorable

A person becomes a criminal when he or she perceives more favorable than unfavorable consequences to violating the law

Differential associations may vary in frequency, duration, priority, and intensity

The process of learning criminal behavior by association criminal and anti-criminal patterns involves all of the mechanisms that are involved in any other learning process

Although criminal behavior expresses general needs and values, it is not excused by those general needs and values, because noncriminal behavior expresses the same needs and values

Siegel, Larry J. "Chapter 7 Social Process Theories." Criminology: The Core. Belmont, CA: Thomson/Wadsworth, 2008. 172-74. Print.

0 notes