Here to talk about all the things I don't get to: Art, Politics, Sports, Beer, Wine, Food, History, &cetera. No copyrighted or mature content, or get out!

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

FAVORITE MOVIE REVIEWS: #9 THE THOMAS CROWN AFFAIR, John McTiernan

My ninth favorite movie is perhaps my most embarrassing. The Thomas Crown Affair is fundamentally a date movie that happens to be about a heist. And call me a liberal fruit bat, but the film articulates some very problematic values.

However, The Thomas Crown Affair benefits from being one of my favorite movies from my adolescence and does a lot of things right. One of these is its representation of New York City, which is not accurate in detail as much as in spirit.

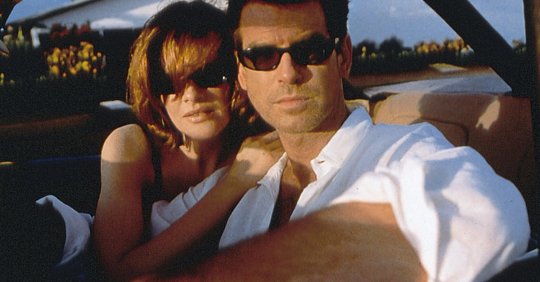

As an adult I appreciate the relationship between Thomas Crown, played by Pierce Brosnan, and Catherine Banning, played by Rene Russo. There are no easy answers in the movie or in their fun yet troubled romance.

Although The Thomas Crown Affair is shamelessly materialistic its moral strength is its honest amorality. It never mistakes its main characters’ drives with a higher sense of right and wrong, which is sadly becoming the norm in today’s media.

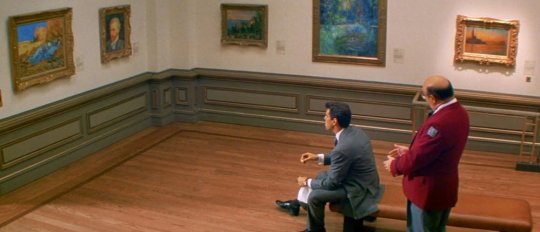

Thomas Crown is a Wall Street Mergers and Acquisitions giant with a fondness for one particular painting--Noon - Rest from Work by Vincent Van Gogh. He affectionately calls it “Haystacks.”

Late for work and stuck in traffic, he leaves his personal chauffeur in front of the Metropolitan Museum of Art to view the painting from a bench the impressionist wing. It should be mentioned that Crown brings a briefcase containing his lunch, which he eats in the museum.

He shows up later in the day at the Wall Street headquarters of his company Crown Acquisitions, having accidentally left his briefcase in the museum. Crown spends the rest of a busy day looking at his watch, waiting for the day to finally end. Crown finally leaves the office with another briefcase and returns to the Met.

I should mention that over the course of the day, a foursome of Eastern European thieves smuggle themselves into the museum hidden inside a Greco-Roman Horse (“Trojan Horse”) preparing to heist the very same wing Crown frequents. Their heist is unrealistically complex--involving crawling through air ducts, sabotaging the air conditioning and an airlift via helicopter.

When Crown arrives, he discovers the nefarious goings on and draws museum security to it. Security thwarts the art thieves before anything is stolen. But not quite.

1999 audiences knew from the trailer that Thomas Crown would steal one of the paintings. But in fact, the entire heist was orchestrated by Crown. While the impressionist wing is sealed and the thieves apprehended, Crown slides under the closing gate, steals one painting off the wall and stashes it in a briefcase hidden under a museum bench. He left the briefcase in the Museum intentionally!

And Crown is only able to make his escape because one of the gates is wedged open by the second briefcase he brought work. We later learn the briefcase was loaded with titanium.

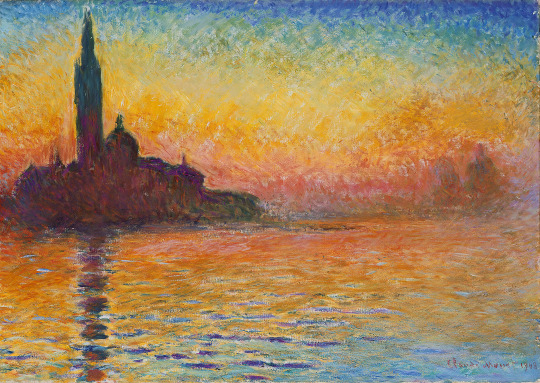

Crown does not steal his “Haystacks.” Instead, he steals a painting by Claude Monet San Giorgio Maggiore at Dusk. The movie sets up the painting early on as the watershed painting by Claude Monet that founded the Impressionist movement, worth $100 Million.

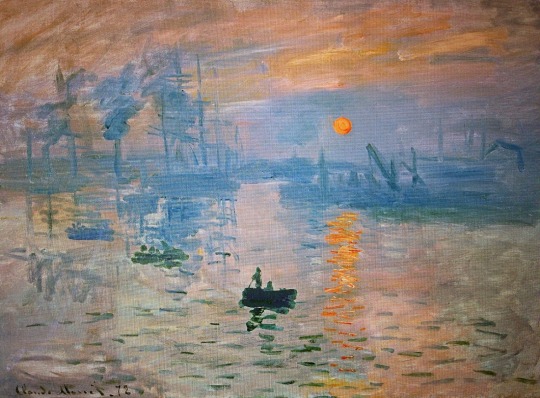

(It should be mentioned that this backstory is made up for the movie. The Claude Monet painting that founded the Impressionist movement is named Impression, Sunrise. It is actually housed in Paris and its subject matter is superficially similar to San Giorgio Maggiore at Dusk, though less dramatic.)

This is our first insight into Crown’s personality. Crown spends the early part of the movie fantasizing of an easier life, like the man enjoying a siesta in Noon - Rest from Work. But it is a facade. Crown is after the drama, dynamism and richness embodied in San Giorgio Maggiore at Dusk.

The above synopsis is only approximately the first twenty minutes of the film. The rest of the movie focuses on the investigation of the robbery. On the case are two NYPD detectives (“Michael”) McCann and Paretti--played by Denis Leary and Frankie Faison.

Having four thieves in custody, they want to treat the case textbook and overlook some of the unusual details. But they are joined within the first hour of their investigation by a Private Investigator named Catherine Banning, played by Rene Russo.

Her job “is the painting.” Already a nuisance to the detectives, she sits in on the Witness ID of the thieves, in which Thomas Crown is the witness. Banning gives Crown several suspicious glances, the gears in her mind turning.

After doing some research Banning discovers Crown has a habit of bidding on paintings by Claude Monet at auctions. She becomes certain that he stole the missing Monet, and after she resolves other details of the robbery McCann and Paretti believe her.

The rest of The Thomas Crown Affair involves Banning’s attempt to retrieve the missing Monet by seducing Crown--who also appears to be seducing her. While the plot develops it becomes unclear to both whether Banning is after the painting or Crown.

Whether or not The Thomas Crown Affair lands depends on its execution of the romance between Thomas Crown and Catherine Banning. More than half of the movie conforms to the plot structure of any modern romantic film. However, The Thomas Crown Affair deviates from romance tropes in several ways that give the film life where another film’s story and characters would drag.

(SPOILERS BELOW)

This is not to say that there are not several romance tropes littered throughout the movie. For instance, two love triangles are forced throughout the movie--involving Detective McCann and a young woman seen dancing early in the film with Crown. One of these love triangles even leads to a misunderstanding that makes Banning betray Crown to the police in the film’s climax.

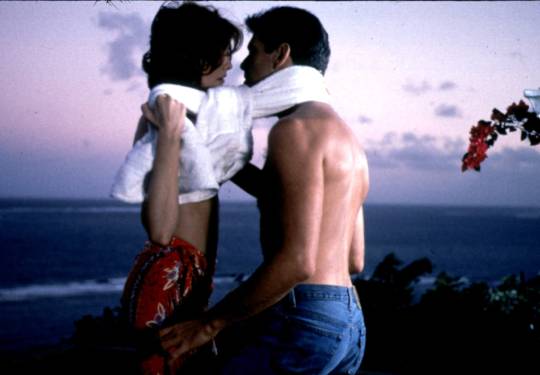

Banning is also led astray by Crown’s wealth and privilege--a tropey characteristic of female romantic leads all the way into the 21st Century. This would not be distracting except that it occurs during a sequence in the Caribbean island Martinique where the film’s pace otherwise grinds to a halt.

For reasons to be discussed, these appear to be problems with the script from its most early drafts. But The Thomas Crown Affair starts to circumvent romance tropes with its first shot. If there is a theme in The Thomas Crown Affair I have come to respect, it is the couple’s incongruent needs. Thomas Crown is attracted to Catherine Banning because of personal insecurity. On the other hand, Banning is attracted to Crown because he is handsome, receptive and fun to be with.

Crown’s insecurities regarding his love life are first stirred up in his first scene when his therapist questions in session whether a woman could ever trust him. In Crown’s relationship with Catherine Banning, he tries to prove that he trusts her as opposed to earning her trust.

From this context, Crown cannot resolve by himself his insecurity about whether a woman can trust. He is going about it wrong. What’s more, trust issues are only Crown’s hangup, not necessarily Banning’s.

Crown’s insecurity is not resolved at the end of the film. At a height of tension in their relationship, Crown promises Banning he will return the stolen Monet to prove that he trusts her. Instead she passes the information to the police.

This turn of events is perhaps the strength of The Thomas Crown Affair as a romance film. It is true that Banning sides with the police in part because of a misunderstanding about Crown’s relationship with another woman. This sort of misunderstanding is typical of Hollywood romance films.

On the other hand, the film avoids a more problematic romance trope by not stating whether Banning should choose Crown or the police. Romance films are typically coded so that a couple, especially the female-gendered half, should choose their romantic interest over their other values or responsibilities. But The Thomas Crown Affair does not even make the case that Banning should side with Crown over the police.

A climactic chase follows between Crown and the police inside the Met. Crown not only returns the painting while evading the police, he steals another--The Banks of the Seine at Argenteuil by Édouard Manet. The painting by Manet is what Banning points to on their first date, saying she would steal that one if given the choice.

Banning goes to the Wall Street Heliport where Crown asks her to meet him. But he has already left and his associate gives her the painting instead. A generous gesture, but Banning does not keep the painting. She returns it to the police instead.

In that entire sequence, Crown shows that he did not fully trust her. And Banning does not reciprocate Crown’s further doting on her.

Catherine Banning’s attraction to Crown is based less on her emotional needs than for the thrill. As Crown says on their first date, “You like the chase.” This aspect is consistent with Banning’s counterpart in the 1968 film, Vicki Anderson as played by Faye Dunaway.

However, one of the major deviations between the 1999 movie and the original 1968 The Thomas Crown Affair is the remake’s “happy” ending. Crown arranges to sit behind Banning on her flight back to Europe and draws her attention by speaking in a Scottish accent.

The scene is ambiguous as to the couple’s future. The fact that Crown speaks in a Scottish brogue for his last line is a callback to the couple’s first date, when he says the hardest part of attending Oxford University was “learning to talk.” Crown finally feels free of the pretensions of English and American culture.

At the same time, Crown and Banning’s needs in the relationship are so different that it is foreseeable they are not a long term match.

As a film romance, The Thomas Crown Affair is refreshing because its romantic leads are not necessarily perfect for each other. They have their own motivations that are never completely reconciled or resolved. And that is more true to life than most Hollywood romances.

The Thomas Crown Affair’s script is written with a curious indifference to materialism. In today’s world, its tone may come off as dissonant. But understanding its perspective requires consideration of not only the era when it was written but the people involved in making the film.

The Thomas Crown Affair was one of the first films produced by Irish DreamTime, a production company founded by Pierce Brosnan and Producer Beau Sinclair. By the time a Director was signed, at least one version of the script was already being drafted. The best explanation why the film conforms to romantic comedy schlock is that its first draft was written to do so.

The early version of the script appears to have remained intact, since writing credits were still retained by Leslie Dixon and Kurt Wimmer. And since Pierce Brosnan was a producer, this means that The Thomas Crown Affair was intended as a vehicle for Brosnan. This is made apparent in the Martinique sequence, which is also where the film’s perspective on materialism is its most loud.

In the exact middle of the film, Crown takes a holiday with Catherine Banning in his island estate. As intimate and seductive as the setting is, Crown also advertises his lavish lifestyle to Banning. His seduction of Banning becomes more obvious when he offers her even more money than her commission to run away with him.

This sequence was likely included at the behest of Actor-Producer Brosnan himself. The actor has a well known attraction to tropical locales and even maintains a home in the Hawaiian Islands today. The ambiguities regarding Crown’s criminality or immorality would then be the product of indifference by the Writers and production staff.

This part of the film stands out in the 21st Century because of several scandalous stories involving Caribbean criminal havens, including the Paradise Papers and Jeffrey Epstein’s estate on Little Saint James in the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Obviously these scandals were not in the mind of the Producers when the movie was shot in the late 1990s.

But Thomas Crown is also represented ambiguously throughout the film. He is a remorseless criminal who has his hands dirtied by other schemes--bribery and offshore banking. This is consistent with the original 1968 film where Crown was more a villain than antihero. But more than the 1968 film, Thomas Crown is humanized as a protagonist and romantic lead. By association his values are also normalized.

Director John McTiernan’s similarities to Thomas Crown make the film’s perspective on materialism and white collar crime suspicious. McTiernan did more than direct. He also (uncredited) rewrote the script and used his own property and vehicles in the film.

McTiernan’s biography is also suspect. In 2000 McTiernan wiretapped a film Producer and later lied to Federal Investigators twice. Prosecution would drag until 2013 when McTiernan was finally sentenced to twelve months in prison.

During McTiernan’s first sentencing in 2006, the presiding judge publicly stated John McTiernan thought he was “above the law,” and “lived a privileged life and simply wanted to continue.”

There is reason to believe that McTiernan based Thomas Crown on himself during his rewrite. Thomas Crown is shown not to be attracted to fame or a cushy lifestyle. Instead, he is a thrill-seeker with a death wish.

But Crown’s motives are never stated explicitly in The Thomas Crown Affair. Furthermore, they are muddied by the existence of a forged Monet in Crown’s possession. The forged painting is eventually discovered by Catherine Banning. Although Crown needed the real Monet to commission the forged Monet, we learn by the end that Crown no longer had the stolen painting when he first met Banning.

Although the forged Monet tricks Banning, this could not have been Crown’s intent when he commissioned it. The best explanation is that Crown intended to trick the police.

More than that, it means Crown committed his theft intent on being found out. This is curiously similar to the judge’s description of Director John McTiernan--that he thought he was “above the law.” McTiernan’s detachment from the consequences of lying to Federal Investigators twice also echoes Crown’s arrogant disrespect for the police.

There are also sociological reasons The Thomas Crown Affair is ambivalent about wealth and materialism. Public opinion about Wall Street and the U.S. financial industry was not as negative in 1999 as it is in 2021. This is partly a result of politics changing in response to current events.

At the same time, the Wall Street boom of the 1980s and how it changed New York City were still fresh in the public consciousness of 1999. Especially in 1999, where big business was not yet politically divisive prior to the Dot-Com Bust.

The indifference the public had for big business is embodied by Detective McCann. By the end of the movie, although Thomas Crown has outsmarted the police and museum security, McCann admits to Catherine Banning that he does not really care about catching Crown.

McCann implies that compared to cases of domestic violence and human exploitation he usually investigates, the art heist by Crown is a victimless crime. The stolen paintings only matter to “very silly rich people.”

Detective McCann is held up throughout the film as its moral center. He has legitimate care and respect for Catherine Banning--even though it is shamelessly teased as a love triangle. He is motivated to solve the case from a sense of professional responsibility. In his last scene Banning even tells him, “You’re a good man, Michael.”

But McCann’s indifference to Crown’s crimes is The Thomas Crown Affair’s moral failure. The victims of art theft are not just the owners but the public itself. Pop culture pre-Enron was similarly indifferent about fraud and white collar crime, believing the victims were only the rich and wealthy.

This indifference is a product of the era. The world would learn very shortly that costs of financial fraud and white collar crime are felt more by society than by the financial industry itself. But to Hollywood and audiences in 1999, Thomas Crown’s art theft and financial crimes were all victimless crimes.

An aspect of The Thomas Crown Affair that deserves credit is its representation of New York City. The city depicted in the film is different from the experiences of most New Yorkers, even in 1999.

Although the film is not always shot in the correct location, the city is represented well in spirit. Early in the movie, a truck driver making a delivery to the Met gripes when Thomas Crown crosses into his lane. Detective McCann similarly expresses contempt for New York City’s social circuit in a manner often overhears. “I love this neighborhood, some of these broads are wearing my salary.”

An AIDS Research Ball hosted by BVLGARI is another realistic part of New York City culture in that AIDS activism had become mainstream by the late 1990s.

The Thomas Crown Affair is shot in a part of New York City that is inaccessible to most people, yet widely advertised. And it is represented in film authentically and amorally--if for no other reason than because the film was shot almost entirely within the city.

Perhaps the most widely entertaining aspect of The Thomas Crown Affair is its contribution to the heist film genre. Heist films are different from other crime movies in that the narrative usually follows the criminal’s or robber’s perspective.

Heist films are also preoccupied with how the criminal will pull off the caper. They differ from detective films where catching and identifying the criminal are the lingering mysteries.

But The Thomas Crown Affair is different from other heist movies in that the finer details of Thomas Crown’s capers are never shared with the audience. For instance, when Crown steals the Monet we are left to wonder how he evaded museum surveillance. Catherine Banning offers an explanation, but the question is never answered for certain.

Another mystery lingers when Thomas Crown steals the Manet at the end of the film. Absolutely no hints are offered as to how he managed to steal it. Part of the attraction of films like these is they leave audiences to guess how certain events occurred.

My favorite explanation for the stolen Manet is that Crown had a mole working at the Met steal the painting beforehand. That also explains how Crown obtained the information necessary to steal the first painting.

Catherine Banning’s explanation for why museum security failed to capture the first theft is that a heater was left in front of the painting. That is because museum surveillance used infrared cameras that responded to temperature, and a heater would have been just enough to interfere with the infrared camera. I should mention now that this feature of museum surveillance is one of the more far-fetched details in The Thomas Crown Affair. Especially today, since face recognition software is in such demand in cyber security.

Lack of realism in films about art or jewel theft is common within the genre, and especially true of the era’s other films--Mission: Impossible, Entrapment and Ocean’s Eleven.

The purpose of heist movies like this is wonder more than realism. And prior films have been similarly tongue-in-cheek about painting and jewel theft--such including the Blake Edwards comedy The Pink Panther.

Films like The Thomas Crown Affair are not intended to be a blueprint for future criminals. Ironically, The Thomas Crown Affair did inspire one bank robber who got away with the loot using the same costumed diversionary tactic as Thomas Crown in the film’s climactic chase scene.

Even though I have said a lot about The Thomas Crown Affair, there are simple reasons why I am fond of the movie. It is a well-made movie, beautifully shot and secretly intelligent. It is a decent representation of New York City, despite complications in the script and budget.

The movie itself is light and entertaining and leaves it up to the viewer to make up their mind. Yes, it requires some suspension of disbelief. Yet even in that way, it treats its audience as mature adults. A quality rare in action or romantic films of any era.

-ve

NEXT POST--#8 LET THE BULLETS FLY (dir. Jiang Wen)

#the metropolitan museum of art#New York City#pierce brosnan#john mctiernan#thomas crown affair#rene russo#martinique#art#impressionism#claudemonet#edouard manet#vincent van gogh#haystack#san giorgio maggiore#denis leary#surveilance#heist film#aids activism#1990s films#cipriani#magritte#white collar crime#romance#romantic film#pissarro

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

I worked 8 straight hours by will in order to get tipped Gratuity + $40 and am now celebrating with the only woman I can spend alone time with until I get vaxed.

0 notes

Text

Relative and Objective Morality

In light of the recent public shootings that are plaguing the United States, I am reminded of the same definition for two different things. This first one is taken from Albert Camus’ introduction to The Rebel, in the paragraph that begins, “Equally, absolute nihilism, which accepts suicide as legitimate, leads, even more easily, to logical murder.” Translated by Anthony Bower:

They were not this monotonous order of things established by an impoverished logic in whose eyes everything is equal. This logic has carried the values of suicide, on which our age has been nurtured, to their extreme logical consequence, which is legalized murder. It culminates at the same time in mass suicide. The most striking demonstration of this was provided by the Hitlerian apocalypse of 1945. Self-destruction meant nothing to those madmen, in their bomb-shelters, who were preparing or their own death and apotheosis. All that mattered was not to destroy oneself alone and to drag a whole world with one. In a way, the man who kills himself in solitude still preserves certain values since he, apparently, claims no rights over the lives of others. The proof of this is that he never makes use, in order to dominate others, of the enormous power and freedom of action which his decision to die gives him.

The same definition has described something else, albeit stated more succinctly. The writer in this case was Christopher Hitchens, in indictment of the policing policies of New York City instituted by Michael Bloomberg and earlier Rudy Giuliani in Vanity Fair.

This is the height of antisocial behavior, because it ruins the pleasure of others while bringing no benefit to the offender.

What Camus defines as “nihilism,” Hitchens defines as “antisocial behavior.” But they are used to describe different things--Hitchens was writing about people who talk at the theatre.

Beyond these examples, maybe we can recognize something more profound: an example of behavior that is objectively immoral.

I lived in New York City in December 2012. This means on the morning of the Sandy Hook school shooting, the killer passed my neighborhood on his drive from New Jersey to Connecticut.

After that news broke in the afternoon, I walked to a Halal stand for lunch. The cart driver, with whom I had a politely friendly relationship, was a man from Bangladesh. He was angry that afternoon to the point he was almost shaking. Without much prodding, he mentioned that his spiritual beliefs and those of his culture were that children were innocent. The crimes of that morning were almost horrifying to this man.

Years later, a graduate Professor expressed an opinion that morality is totally relative because it is derived totally from a person’s culture. I cannot help but think that this man would probably earnestly believe this perspective is respectful to the Halal vendor. And I am quite sure the vendor would find this white, self-identifying Liberal Professor’s regard for his beliefs condescending.

Yes, morality is defined by culture. But what is culture if not an expression of a people’s relationship with nature? And is a human being not a product of nature itself?

A human must eat or drink in a day in order to survive. Our bodily functions are necessary for our survival and if our body stops functioning we stop functioning. And our bodies are limited by their structure. Most animals occupy habitats that we cannot survive.

Between peoples and individuals, what is good or bad varies based not only on cultural values but circumstances.

Camus refers to an “enormous power” that the decision of suicide gives a person. There are many circumstances where a person’s powerlessness to pain and suffering could justify ending their life, even to Camus. Furthermore, members of certain social circles actually find some forms consensual pain as pleasurable.

Yet human beings are animals by nature. Circumstance will always vary their needs, but a need to live is a part of our nature. And our culture is derived from it.

There is something insidious about the tendency toward moral relativism and cultural relativism, beyond their tendency to patronize cultures that are not American or European. Total moral relativism is an expression that humans are free from culture, and therefore nature itself.

But that is not so much a goal as hubris. We are all fragile creatures our technology and energy is limited by the planet we live on and the Sun we orbit.

Instead of disowning nature, perhaps we should listen to it instead, not just for the planet but for ourselves.

-ve

Sources:

ALBERT CAMUS, The Rebel (Anthony Bower tr, 1st edn, Vintage International 1991)

CHRISTOPHER HITCHENS, ‘I Fought the Law’ [2004] VANITY FAIR <vanityfair.com/news/2004/02/hitchens200402> accessed 27 March 2021

1 note

·

View note

Text

FAVORITE MOVIE REVIEWS: #10 DREAMS, Akira Kurosawa

Dreams earns a spot as one of my favorite movies because it inspires childlike wonder and mature reflection in me. Its images inspire wonder in me that I only ever seem to feel within my own dreams. At the same time, I am moved by the movie’s careful treatment of its main theme--how to live in a world where the only certainty is our own mortality.

Dreams is a thematic sequel to Ran, the 1985 epic period film that earned Writer-Director Akira Kurosawa an Academy Award nomination for Best Director. Several critics have described Ran as pessimistic and nihilistic. Some have even interpreted the film as evidence of Kurosawa’s depression during the later part of his career.

Kurosawa’s later life certainly contains elements of tragedy and hardship, but Kurosawa’s outlook should not be described as nihilistic. Ran ends with a moral that human folly, not divine will, caused the film’s human tragedies.

Dreams continues this theme. It explores the subject of mortality and fear of death and seemingly concludes that this fear is the cause of human folly, and its crimes against nature.

Dreams shares many creative elements with Ran and Kurosawa’s earlier film Kagemusha. These elements are worth an entire treatment in and of themselves. Instead, I will discuss the themes and artistic aspects of the movie that make it one of my favorite films.

Dreams is part of a subgenre of movies that are anthologies of dream sequences--a genre that includes some of the most famous films by Luis Buñuel. Even though Buñuel was a surrealist with an interest in dream interpretation, Dreams may be a clearer window into its artist’s psychology than are Un Chien Andalou or The Phantom of Liberty. This is because Buñuel created structure in his scripts by inserting conscious political themes and dream sequences provided by his collaborators--Salvador Dalí and Jean-Claude Carrière.

Kurosawa frequently attempts to replicate the experience of his dreams. His most frequent device is to end each dream sequence with a cliffhanger, which he does in dream sequences “Sunshine Through the Rain,” “The Tunnel,” “Mt. Fuji in Red,” and “The Weeping Demon.”

Kurosawa also tries to elevate the dreamlike quality of each dream sequence. The most successful instance is in “The Tunnel,” when Kurosawa as a soldier sighs with relief after walking safely through a tunnel path. There is no reason stated reason for apprehension, except that a dog illuminated in a red aura blocks the soldier from walking any other direction.

Details like these communicate Kurosawa’s experience within the dream. Another device with the same effect occurs at the opening of the dream sequence “Crows.” Kurosawa studies the Vincent Van Gogh painting The Langlois Bridge at Arles with Women Washing. The sequence cuts to a live action image of the painting and Kurosawa steps into the foreground from outside the frame, implying he is walking into the painting. Later in the sequence, Kurosawa runs through several of Van Gogh’s unfinished paintings, searching for the artist.

For reasons I will elaborate further below, Kurosawa’s attempts to replicate the dream experience sometimes fall short and weigh down the movie. Yet they are most effective where they distort space and time. One of the best examples is in “The Peach Orchard,” which I will return to below.

Some details of Akira Kurosawa’s biography inform the meaning of Dreams. Kurosawa paid attention to detail regarding his childhood home and his mother’s mannerisms in “Sunshine Through the Rain.” Kurosawa is also said to have taken mountain climbing as a hobby as a young man, which informs the sequence “The Blizzard.”

The movie’s themes of artistry, suicide and the Pacific War all affected Kurosawa’s life. Yet although Kurosawa was a soldier in “The Tunnel,” the real Kurosawa never served in Japan’s Imperial Army.

Kurosawa’s career has at times put him at odds with Japanese culture. His early films were at times criticized for emulating a Western style. He did draw on literature by Shakespeare, Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky. And was also quoted saying the Occupation changed the Japan’s film industry in some positive ways. It’s conceivable his critical relationship with the Japanese film industry may have contributed to Kurosawa’s industry struggles between 1965 and 1985.

The theme of suicide in Dreams suggests Kurosawa’s tone may also be an example criticism directed toward Japanese social values. Kurosawa was born in 1910 during the Imperial Period of Japan, where ideals of militarism and Samurai culture would have still been preserved.

In “Sunshine Through the Rain,” young Akira is shut out of his home by his mother and told to either commit suicide or to find kitsune, spirit foxes, and beg their forgiveness. Walking away from his home, the camera zooms out so he remains the same size in the foreground while the background shrinks. Literally, young Akira is growing up. However, he is leaving his home to beg forgiveness, not to commit suicide.

If “Sunshine Through the Rain” was an authentic dream, Kurosawa as a child may have emotionally understood suicide in its cultural context. And this is supported by details at the end of the dream sequence.

In every dream sequence Kurosawa rejects suicide when given the choice. Yet Kurosawa himself attempted suicide in 1971. Japanese ritual suicide (seppuku) is referenced in this sequence as he is given a dagger to disembowel himself.

Seppuku is referenced in one other sequence--“The Tunnel.” In that dream sequence, Kurosawa tells the spirits of several dead soldiers that as a POW he felt like dying, that it would have been easier. The statement refers specifically to the expectation during World War II that Japanese POWs were to commit suicide--by seppuku or by other means.

Other references to suicide in Dreams do not involve sepukku. But Kurosawa’s understanding of suicide as a child, when he presumably first dreamed “Sunshine Through the Rain,” would have come from his cultural context as Japanese. Although Kurosawa may not have intended to criticize social norms regarding suicide directly, as far as he was criticizing suicide itself he was doing so from his own cultural context.

The theme of suicide is a small part of the larger theme of Dreams--fear of mortality. Western critics tend to misunderstand this theme within the movie and believe Dreams as ‘misguided’ environmentalist preaching.

Yet the environmental themes in Dreams are not as cohesive or detailed. The theme regarding mortality is present in “Sunshine Through the Rain,” “The Blizzard,” and “Crows.” The only other dream sequence with only an environmental theme is “The Peach Orchard.”

Both themes are presented at the same time in “Mt. Fuji in Red,” “The Weeping Demon,” and “Village of the Watermills.” I believe this caused critics to misunderstand Dreams. Kurosawa was concerned about the environment and probably wanted to advocate for a harmonious relationship with nature. But his message about morality is the more consistent and more clearly articulated theme in Dreams.

As far as Dreams is an authentic representation of Kurosawa’s inner life, it also provides insight into the way he saw women throughout his life. This is important because Kurosawa has been criticized for his representation of female characters throughout his filmography.

The first three dream sequences heavily feature women. “Sunshine Through the Rain” shows young Akira Kurosawa intruding into a Foxes’ Wedding. His mother responds by refusing to let him into the house.

An important detail is that the Foxes’ Wedding is a traditional Japanese wedding and the female and male foxes are separated based on gender. For a young child, this detail represents an understanding of sexual difference. And that understanding separates young Akira from his mother.

“The Peach Orchard” contains a similar theme. However, young Kurosawa instead leaves his sister to chase after a young girl who is in fact the spirit of a peach sapling.

In “The Blizzard,” Kurosawa is now a young man climbing a mountain during a snowstorm with three male companions. When Kurosawa finally succumbs to exhaustion, he is visited by a Yuki Onna (literally “Snow Woman”). He pushes her away as she tries to comfort him and as the storm subsides Kurosawa and his companions make for camp.

Female characters only feature heavily in two of the remaining dream sequences in Dreams. This fact strongly suggests Kurosawa’s emotional life was not as strongly influenced by women after adolescence, a possible explanation why women are frequently not protagonists in Kurosawa’s filmography. More than that, female characters in Kurosawa’s dreams are all either family or magical creatures until the dream sequence “Mt. Fuji in Red.”

One last theme worth discussing is the role that Vincent Van Gogh played in Kurosawa’s career. Vincent Van Gogh appears as a character in the dream sequence “Crows.” Kurosawa was well known as a painter and used his paintings as storyboards. His paintings have a wild quality and use a surreal, vibrant color palette--which influenced his use of color in Kagemusha and Ran.

Embarrassingly, it took me a few years and several rewatches of Dreams to realize Van Gogh was Kurosawa’s primary influence as a painter.

Dreams is one of my favorite movies. However, it is Number 10 because it has some fundamental flaws.

I have mentioned that the movie attempts to replicate the experience of a dream with mixed success. The failures are mostly in scenes when the protagonist observes and responds to his surroundings. The device works in dream sequences such as “The Tunnel” because the script viewer shares the character’s apprehension. The tunnel is shot pitch black and a threatening dog emerges from the tunnel before Kurosawa enters.

Other sequences are less successful. In “The Weeping Demon,” Kurosawa walks from the ruins of a city onto a desolate slope. There is no shot establishing what Kurosawa sees as he changes his path from one direction to another. This goes on for several minutes before any payoff.

Other dream sequences have the same problem with pace. “The Blizzard” opens with approximately ten minutes of Kurosawa and his companions hiking through a snowy mountainscape. Although we learn that the men are lost, no dialogue or action establishes that the mountaineers are lost or confused. I must confess that I have fallen asleep more than once in the early parts of the dream sequence “The Blizzard.”

Another sequence with this problem is “Crows.” The second half of the sequence shows Kurosawa chasing after Vincent Van Gogh while inside the artist’s unfinished paintings. Unlike “The Blizzard,” this sequence does not harm the narrative of the dream sequence because the first half already established two things. It established that Kurosawa is inside Van Gogh’s paintings and that he is chasing the artist himself.

One possible reason the film makes these mistakes is budgetary. Shooting vast landscapes would have required the resources to shoot on location or create large elaborate sets. Some sequences do exactly that--“The Peach Orchard” and “Village of the Windmills.”

Dreams had a large budget for a Japanese movie of its time. But at approximately $12 Million US, the budget would have limited what could be done.

The mistakes regarding the pace in the end fall onto the screenwriting. The runtime of Dreams is 119 minutes. Trimming “The Blizzard” and “The Weeping Demon” would have solved these problems and still kept the runtime over 90 minutes.

Critical characterization of Dreams as self indulgent is probably correct, and is the best explanation for these decisions. But it is also a creative decision Dreams has in common with the earlier Ran and Kagemusha. Both run nearly three hours and include several lingering shots--a stylistic trademark of Kurosawa’s later films. The criticism that Dreams is self indulgent is less an indictment on this style than it is on the quality of the movie itself.

However, Akira Kurosawa’s self indulgence is forgivable because Dreams is such a pretty movie to look at. Many sequences were Kurosawa’s first experiments with digital special effects, which are never used in a distracting way.

Beyond that, several shots in the movie are made using experimental cinematography to great effect. One shot is in the sequence “The Peach Orchard.” Young Kurosawa is confronted by the spirits of several cleared peach trees in the form of hina-ningyo--ornamental dolls representing the Japanese Imperial Court. When young Kurosawa expresses his grief for the trees, the spirits respond by performing a traditional dance for young Kurosawa.

The dance takes place on a hillside that is not especially steep. Yet the spirits appear at the same approximate distance from the viewer, as though they are on the same display as a hina doll set. Such a shot is obtained by using a strong telephoto lens, which tends to compress the depth of frame in a shot. For this effect, Kurosawa would have had to shoot this image from at least 250 meters away.

“The Tunnel” is another surprising sequence for its cinematography. Specifically, the dog that emerges from the tunnel is illuminated in a red aura that contrasts with the color palette of the rest of the scene.

Modern viewers might assume this was accomplished with simple digital editing. In fact, the red light comes from a street light that is barely visible throughout the scene. It does not shine brightly until the dog appears and is barely visible as faint glare on the street gravel.

How this shot was made confuses me. I am certain that the effect is caused by increasing the brightness of the light because the red aura touches Kurosawa’s protagonist in some shots. But I am not certain the shot could be illuminated from a street light unless the set was already shot in low light. Other details suggest the sequence was shot entirely in low light.

These and other sequences in Dreams create surreal visual splendor that is only glimpsed in the earlier Ran and Kagemusha. Although Dreams was not nearly as commercially successful, it is less trapped by its genre and is one of the best movies to look at.

Some of the sequences appeal to me personally because they are things I have only seen in my dreams, such as the mob of crows at the end of “Crows.” Other images remind me of what I imagined as a child or the paintings I would have wanted to make when art was a greater part of my life. For these reasons, I recommend Dreams to any viewers who look for that certain visual quality in what they watch.

But Dreams also has an important message about mortality and loss. For that reason, I recommend Dreams to anyone dealing with grief and recovery.

-ve

NEXT POST--#9: THE THOMAS CROWN AFFAIR (dir. John McTiernan)

#akira kurosawa#dreams#dreamscape#movies#cinema#cinematography#90s#japan#japan aesthetic#photography#painting#kagemusha#ran#luis bunuel#salvador dali#vincent van gogh#van gogh

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

ANNOUNCEMENT: (New Series) FAVORITE MOVIE REVIEWS

Starting with this post, I am starting a new series reviewing my ten (10) favorite movies of all time. Self indulgent? Possibly. But there are reasons I am choosing this topic.

First, the reason I started this blog was to have a place where I could share my opinions on things that I had in common with friends from high school and college. Among those subjects has been sports, politics and film. In adulthood, I have been surprised how few people share these and other interests--and are able to speak about them in a respectful way. Perhaps I should have appreciated my circle of friends when I was younger than I did.

But in particular, most people I meet don’t think as carefully about movies as I used to expect. So I have decided to come here as a place to exercise my thoughts about film, which need a good workout.

Second, I am choosing to write about my favorite movies for a couple reasons. Doing so will give the reader a sense of who I am, so this is a good project to start the blog early on.

Also, this is a good way to express myself in a healthily modest way. Few of the movies in my “Top 10” list are movies that I consider the greatest movies of all time. They are movies I like more than the rest. Some are a little embarrassing. When reviewing these movies, my goal is to be honest about their shortcomings. Just because something is great does not mean you have to like it. And just because you love anything, does not mean it has to be perfect.

Third, the purpose of these blog posts are a writing exercise. True, these essays are nonfiction. And as an English professor once said, they are all TTTP: “Talking to the Paper.” But creating prose that is readable, digestible and timely produced is an important skill for anyone who writes. And I hope to hold myself to that in this series of essays.

I hope to use this blog for other purposes too. There are things going on in the world of politics that people overlook, not because they are boring but because demagogues assume we won’t care--or worse, prefer that we do not know them. The world emerging from the cocoon of the pandemic is fundamentally changing. I hope to share my thoughts about it all. But first I must get used to sharing. And that is why I am starting this series.

ve

NEXT POST--#10: DREAMS (dir. Akira Kurosawa)

0 notes

Text

MARTIN SCORSESE VS. MARVEL

Martin Scorsese’s comments these past years on Marvel’s MCU, and how they have been covered by the entertainment press, labeled him a snob or cranky Grandpa for an entire generation. You can say what you want about Marvel Studios--and I tend to have much more negative to say about the Marvel films than most people. Truth be told, some of Scorsese’s comments have been problematic. But his opinions have been treated aggressively when they are mostly harmless and, should be unpacked with care instead.

First we should be familiar with what he said about Marvel before rushing to judgment. According to The Guardian:

“I tried, you know? But that’s not cinema. … Honestly, the closest I can think of them, as well made as they are, with actors doing the best they can under the circumstances, is theme parks. It isn’t the cinema of human beings trying to convey emotional, psychological experiences to another human being.”

The implication within his statement is that movies that don’t communicate psychological experiences are not “cinema” but a different kind of art. True, he did sort of walk that back by saying the recent superhero movies are not the “cinema of human beings trying to convey experiences to another human being.” It could be he realized saying the Marvel movies should not be called “movies” or “cinema” altogether would be even more harmful than his criticism.

But the problem remains Scorsese took an elitist tack with the Marvel MCU--an implication that the franchise lacks artistic value. Even though that tack seems harmless it opens the door to dangerous ideas, including the Pandora’s Box of governments making art illegal for “lacking any artistic value.” (Miller v. California, 413 U.S. 15 (1973))

Don’t get me wrong, I don’t think Martin Scorsese intends further censorship of movies for a few reasons, including his professional relationship since the 1980s with members of China’s Fifth Generation of Chinese Filmmakers.

But also because Scorsese’s movies have long flown in the face of industry censorship. His earliest movies were notorious for pushing the bounds of acceptable language in film. The Last Temptation of Christ was shelved for ½ a decade due to protests by religious groups. And his indie followup to the failed production featured a man and woman discussing the novel Tropic of Cancer--the object of an infamous obscenity trial.

Scorsese is not advocating for further censorship of film, but his statements lend themselves to this bad intent.

So should we all be concerned that Scorsese’s opinion will justify a new censorship regime based on the “artistic value” of any movie? Hardly, and for one obvious reason: Scorsese is not powerful enough to lead any such political movement. He does not even own his own movies.

On the other hand, major studios owned by Disney, Warner Brothers and others own the rights to these movies and have always wielded control over what is, and is not, acceptable in the art they own.

And this has led to some questionable creative decisions--including insertion of Right Wing political messages in recent Marvel and James Bond films. Since Disney owns Pixar, Marvel, Lucasfilm and now Fox, the studio has control over not only what messages can be in any movie, but whether a movie gets made at all.

Censorship of film and other art, if it comes, will not come from culture snobs. It will come from major corporations including Disney and its subsidiaries--but also Time Warner, Facebook, Amazon, Google and Apple.

1 note

·

View note