Text

Draft Conclusion

Kerry Ann Lee uses her work as an outlet to not only respond and reflect on her own personal experiences with her cultural context, but as a way to prescribe this contextualisation to her audience and especially those at the same cultural crossroad as herself. Through her work, Lee has been able to define her hybridity of cultures and in reference again to Homi Bhabha, was able to create her own ‘third space,’ a combination of her different cultures and experiences in order to create a new identity and to answer these questions of who am I? Who are you? And what makes us different.

0 notes

Text

Gender

When comparing the traditional treatment of women by Māori to the treatment of women in Western culture, we can see stark differences that show how woman are held in vastly different hierarchical positions between the two.

Traditionally in Māori culture men and woman were seen as equals and both had defining roles not only in their society, but in their proverbs and the way in which they saw the world. “Both men and women were essential parts in the collective whole, both formed part of the whakapapa that linked Māori people back the the beginning of the world”(Mikaere, 1). Not only were the ways that woman were seen in Māori’s eyes equal, so were the ways they were raised to be treated in society “elders set the example of men and women respecting and supporting each other, and working alongside one another”(Mikaere, 1).

Almost in complete contrast to this societal balance, the way that Western culture approached gender was extremely dominating. In old Western culture “The head of the family (the husband/father) was in control of the household”(Mikaere, 2). As we can see, this clear hierarchy extends further than the views of the collective, and was being enforced in peoples own homes. This extreme unbalance was evident in Western culture, and after colonising New Zealand these ideals and laws started to also impact Māori’s views on this, especially in racially mixed partnerships, because in the eyes of the West, woman were more property than people “[after marriage] they changed from being the property of their fathers to being the property of their husbands”(Mikaere, 2).

Works Cited;

Mikaere, Annie, “Maori Women- Caught in the Contradictions of a Colonised Reality,” Faculty of Law - University of Waikato, 1994.

Simmonds, Naomi. “Mana Wahine: Decolonising politics,” Womens Studies Journal, 2011.

0 notes

Text

Draft Analysis

Feedback on this analysis was relatively positive in the way that I analysed Lee’s culture in terms of the artwork, although I will definitely need to refer back to one of my readings to give supporting evidence on these ideas.

Lee’s work below, ‘Trade and Exchange (hoard anything you can’t download)’ Shows explicitly how she expresses a loose form of cultural context throughout her work. The piece takes the form of almost a gallery, or exhibition of her life as a visual expression of her individual identity. The objects in the display draw you not to a singular place or culture, but to various different places and experiences throughout her life, “All identity is experience”(Selasi, 11:06). Although the majority of the artefacts being displayed in this artwork are inherently ‘Western’, she still pays homage to the experience and connection she has had with other cultures, such as the dragon head from the Chinese side of her family.

Lee, Kerry Ann. “Trade and Exchange (hoard anything you can't download).” 2017, Digital print on acrylic, lightbox, Pātaka Art + Museum, Porirua, NZ.

0 notes

Text

Cultural Appropriation

The preservation of cultural integrity and respect is a key part of maintaining the traditions and strength of a specific culture. This integrity is damaged when certain traditions and cultural aspects are taken out of their authentic context, taken for granted and stripped of their meaning, with no regard for their history. This type of cultural appropriation occurs a lot in the visual world due to the fact that many people are concerned explicitly with aesthetics rather than meaning. The main character in Sony’s ‘The Mark of Kri,’ has been accused of doing exactly this, by taking strong Māori features and exploiting them for the personal success of their video game, with no regard for the impact this has on its originating culture. Although Sony claim the character has no Māori affiliation, “From a Māori perspective, Rau’s name, moko and taiaha (spear) are Māori”(Schwarzpaul, 3).

This game, and many other examples like it, attempt “ to recover lost aesthetic styles – not, however, the “social, political, economic, and ceremonial institutions on which the aesthetic traditions were dependent and through which meaning was achieved”(Schwarzpaul, 4). Although this may not seem like a huge deal from an outsiders perspective, or even from Sony’s perspective, the savage, and sometimes violent nature of this game, and the nature of other examples of this appropriation projects similar connotations onto the culture as a whole. When people are exposed to a culture, in this case Māori culture, in a way that so strongly contrasts the true nature of its history, we immediately associate these false ideologies with the culture itself. This way of forming false stereotypes in the population is not only disrespectful to its origin, but becomes dangerous and counter productive when these stereotypes (like any stereotype) forms prejudges in the minds of the public.

Work Cited;

Zografos, Daphne. “New perspectives for the protection of traditional cultural expressions in New Zealand.” International Review of Intellectual Property and Competition Law, 2005.

Engels Schwarzpaul, Tina. “Dislocation Wiremu and Rau - The wild man in virtual worlds.” AUT University.

0 notes

Text

Essay Plan

Intro

Who are you? Who am I? What makes us different? These questions of identity have shaped the succession of our collective worldly society in more ways than we imagine, and our reaction to these differences helps to define who we are as a people. The way in which we define people in our society responds almost exclusively to their cultural background, especially when this perceived cultural context contrasts that of those around you.

Introduce Kerry Ann Lee

Body

How do Kerry Ann Lee’s cultural background and link to Chinese, Cantonese and New Zealand culture make it hard to create a strong Identity?

How does the discriminatory history between New Zealand and Asian heritage effect how she feels she fits into society and how is this expressed through her work?

How does she use her cultural hybridity to create this ‘third space’ in her artwork, rather than creating work that feels disjointed?

Images From Exhibition.

These images are relevant to all three points, in the way that they are portrayals of how she blends her cultural background in a singular setting.

Lee, Kerry Ann. “The Many Faces of Paradise” 2017, Hand-cut paper installation, Pātaka Art + Museum, Porirua, NZ.

Lee, Kerry Ann. “Trade and Exchange (hoard anything you can't download).” 2017, Digital print on acrylic, lightbox, Pātaka Art + Museum, Porirua, NZ.

Other images

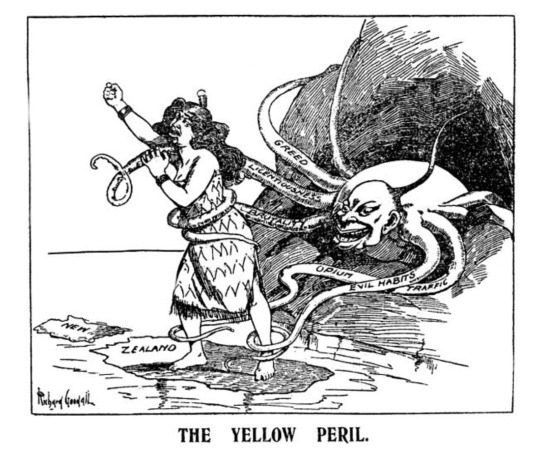

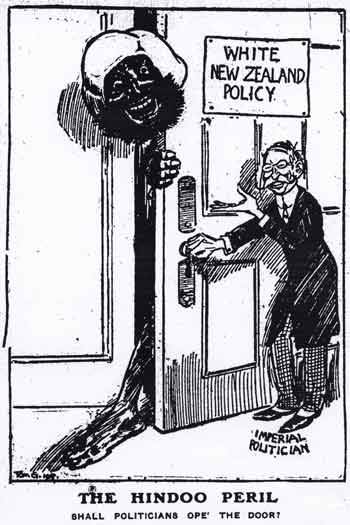

This image relates explicitly to the history of her culture in New Zealand and can be used to show how she responds to this discrimination in her work.

Goodalh, Richard. “The Yellow Peril.” 16 Feb 1907, Illustration, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand Truth Issue 87, paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZTR19070216.2.41.1

0 notes

Text

Hybridity

Hybridity, in the most primitive sense of the word, describes the mixing of two separate parties or identities. This definition supports basic hybridity in terms of cultural hybrids, but to little purpose. In reference to Homi Bhabha, cultural hybridity is described as being a ‘third space,’ meaning that rather than seeing the combination of two cultures as an identity, the output of this cross forms a completely new and self-sufficient culture that can stand alone without the need for any reference to the separate streams that lead into it. “For me the importance of hybridity is not to be able to trace two original moments from which the third emerges” (Bhaha, 211).

This definition doesn’t link explicitly to a cultural identity, but is a very important part of creating one. Bhabha says that this notion of hybridity is the combination of “the genealogy of difference and the idea of translation” (Bhabha, 211). This idea of translation is especially important in forming an identity through hybridity, as in its basic form, translation makes the need for the origin of its output obsolete. This shows that the true value in hybridity comes in the way that it creates something new, rather than just a translation of a different identity. Hybridity is the partnership between various identities, so although the premise of this ‘third space’ is inherently individual, the importance of it, in terms of forming an identity, is that “it bears the traces of those feelings and practises which inform it”(Bhaha, 211) and “puts together the traces of certain other meanings or discourses”(Bhaha, 211).

Works Cited;

Rutherford, Jonathan. “The Third Space. Interview with Homi Bhabha.” London: Lawrence and Wishart, 207-221, 1990.

Mok, Tze Ming. “Race You There.” Dunedin: Otago University Press, 18-26, 2004.

0 notes

Text

Potential Supportive Readings

Looking ahead to next weeks blog post task, I have found a couple of readings that I think will be very helpful to my final essay;

Rutherford, Jonathan. “The Third Space. Interview with Homi Bhabha.” London: Lawrence and Wishart, 207-221, 1990.

Mok, Tze Ming. “Race You There.” Dunedin: Otago University Press, 18-26, 2004.

‘The Third Space’ Will be especially useful in my writing as it describes cultural hybridity, identity and translation as a whole. This is extremely important when looking at people, in this case an artist, practising art that is informed by a different culture than they are presenting it to. The ‘third space’ that is discussed in this text could be defined as this visual output that is produced by these artists.

0 notes

Text

Stereotypes

Racial stereotypes are engrained in almost every culture in the world and almost express explicitly negative characteristics of these certain races. The 2004 TV show, ‘Bro Town’ follows the lives of five New Zealand school boys, and their usually mischievous adventures. The show embodies many of the racial stereo types in our own society, specifically that of pacific island cultures. Of the five school boys, one of these is a Māori boy called ‘jeff da Māori.’ In relation to the stereotypical groupings in Melanie Wall’s text ‘Stereotypical Constructions of the Māori Race in the Media,’ this character is using Māori as ‘the comic Other,’ and whilst the character dissolves certain aggressive stereotypes sometimes associated with Māori, It works to “berate their buffoonish behaviour” (Wall, 42) and enforce “stereotypes such as the innate laziness of the Black man” (Wall, 42). This type of stereotyping is seen even in the opening scene of the first episode of the show where the five boys think they’re in trouble for skipping class and all start to blame each other for various different reasons, but the argument is resolved when one of the Samoan characters blames the Māori character for acting out, purely based on his race, saying “it was Jeff’s fault, he’s a Māori” (Bro Town). This type of character that was laughed at by the public, was perhaps the most explicit portrayal of this form of stereotypical construct, and lies in complete contrary to the portrayal of Māori by the New Zealand kapa haka group ‘Te Waka Huia.’ Te Wake Huia perform to embrace the more traditional, and common values of Māori culture, not just through their use of traditional dance and costumes, but "It's not just about kapa haka but it's about leadership and looking after people and families.” (Stuff). This family orientated group breaks down these commonly misused stereotypes through their pure expression of Māori art in a way that completely contrasts the non-Māori writing in ‘Bro Town,’ from an exclusively Māori perspective.

Works Cited;

Pratt, Ciara. “Five-Time Champions.” Stuff, 26 Feb 2013, http://www.stuff.co.nz/auckland/local-news/western-leader/8351381/Five-time-champions

Bro Town. “Jeff da Maori’s first bed / BroTown.” Youtube, BroTownChannel, 30 July 2009, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eWzZ54_Dft8

Bro Town. “Bro’Town - Season 01 - Episode 001 - The Weakest Link.” Youtube, Thuan Hoang, 5 Sep 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WlAhygXLPao

Wall, Melanie. “Stereotypical Constructions of the Maori ‘Race'" in the Media. New Zealand Geographical Society, 1997.

Panoho, Rangihiroa. “Maori: At The Center, At The Margins.” Headlands: Thinking through New Zealand Art, 1992.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Question

I have chosen to explore question 1 for this assignment.

Select an artist, designer, or collective with Moananui a Kiwa (Pacific) or Asian whakapapa working within Aotearoa New Zealand whose work talks to their cultural context. Discuss the ways that the maker/s reflect and/or respond to their social, political, cultural, and historical experiences through their work. Explain how hybridity and/or diaspora is addressed in their work.

I think this will be an interesting avenue to explore, as I really don’t know anything about non-native New Zealand art. The only New Zealand artwork I have really researched for previous assignments has been very culturally orientated by Māori or European artists. I think this cultural blend will be interesting to research in this assignment.

After some preliminary research, I found the images below that speak of different cultures in New Zealand, through performance, art, and their social context.

0 notes

Text

Pacific Identity

The term ‘Oceania’ has had its definition dramatically altered from generation to generation. What was once considered a simple cluster of southern cultures, has now become “a world of social networks that crisscross the ocean all the way from Australia and New Zealand in the southwest, to the United States and Canada in the northeast” (Hau’ofa, 392). Albert Wendt also talks about this diverse culture by saying “Like a tree, a culture is forever growing new branches, foliage, and roots. Our cultures, contrary to the simplistic interpretation of our romantics, were changing even in pre-palagi times” (Wendt, 120). The ever changing nature of these cultures, and Oceanic culture as a whole, is important to consider when discussing pacific identities “So far these attempts have foundered on the reef of our diversity,” (Hau’ofa, 392) meaning that for years the idea of a collective pacific identity hadn’t been fully embraced, and instead focused on individual differences between these cultures. Without trying to flatten all of these cultures into a singular, Hau’ofa suggests that when we consider these identities, we first have to gain strength as a collective before having the power to celebrate our differences, “As individual, colonially created, tiny countries acting alone, we could indeed “fall off the map”.” (Hau'ofa, 393).

The term “fall off the map” was new to me in Epeli Hau’ofa’s reading but is a very effective phrase in describing the fragility of these cultures and in turn, the importance of preserving them, at the fear of them being gone forever.

Works Cited;

Hauofa, Epeli. “The ocean in us.” The Contemporary Pacific. University of Hawaii Press. 1998.

Wendt, Albert. “Towards a new Oceania.” in Sharrad, Paul, ed. Readings in Pacific Literature. New Literatures Research Centre University of Wollongong, 1993.

0 notes