An ASHT initiative highlighting the sacrifices made by Sikh soldiers in the First World War

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Sikh Platoon Make History Come Alive at Royal Military Academy Sandhurst

Entering the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst, putting my first step on its’ historic soil on a beautiful sunny Friday morning, there is no greater place for me to be right now than here. As I walk past New College, admiring the beautiful whitewash buildings and inhaling the fresh morning air, peacefulness fills me. But right away my attention is drawn by the Sikh platoon in the distance, dressed in 95 British Army combat uniforms – what a sight! As the families of the Sikh regiment arrive, beaming with pride, and with smiles to match, the grand honour of being at Sandhurst on this historic day begins to sink in. All are ready to commemorate the Battle of Saragarhi. Today the commemoration at The Royal Military Academy Sandhurst is to feature a re-enactment by a troupe of 30 Sikh volunteers. The first Sikh platoon to ever parade at this military school.

The Battle of Saragarhi took place on the 12th day of September 1897 on the North-West Frontier of the British Raj, in the now border region of Pakistan and Afghanistan. 21 soldiers from the 36th Sikh Regiment defended an army outpost against 10,000 Afghan and Orakza tribesmen, preventing what would have been a devastating invasion of their homeland.

With over 300 guests in attendance it was an honour to walk around and take in what the family members were feeling before their beloved sons, fathers, and brothers marched out on parade. One lady who caught my eye was Manjit Kaur from Birmingham, the mother of Chamkor Singh. As I approached her, she was hugging her son, wishing him all the best for the parade. Her face filled up with happiness and joy, a mother so proud of her son:

‘I am really happy and proud that my son is taking part in the Saragarhi parade today in Sandhurst. He has worked so hard for this event alongside his colleagues.’ She also mentioned her family’s military history; ‘Chamkor’s uncle was in the military, and my son is carrying the tradition.’

Sukhy Kaur, whose husband Jatinder Singh Sanghera and brother Kalwant Singh, both a part of the 1914 Sikh project, expressed her joy:

‘I am so proud of my husband and brother being part of this prestigious event together. It is lovely to know that they both are raising awareness of our Sikh heritage.’

After finishing off our delicious refreshments, catered for by the traditional Punjab Restaurant, we are invited into the Indian army memorial museum. You cannot help but be in awe of the military feats of the Sikhs, as you see the huge stained glass tribute to the Sikh soldier “1919, Afghanistan” offering a panorama of imperial history, that is infused with sacred memory. On his podium, the commander welcomed the guests to Sandhurst, and proceeded to speak about the Battle of the Saragarhi.

Returning outside, in the afternoon sun, the guests take their seats and embrace this special moment, everyone holding a proud smile. The Sikh regiment, with heads raised high, launch the parade with the Sikh war cry ‘Jo Bole So Nihaal, Sat Sri Akaal - Uttering this one shall be blessed, True is the Timeless Lord!’. Sandhurst stands to attention as the words ripple through the air. The joy and happiness was one to be proudly witnessed, as The Royal Military School of Music joined the Sikh Regiment, marching together in rhythm.

Words cannot describe the reaction of the families, to this epic tribute, marking their glorious history. It is a beautiful moment to take in, an experience to remember, a blessing to be here watching the parade, and a proud feeling knowing that today, the outstanding effort of these 30 Sikhs have made history come to life. They have worked incredibly hard, for over a year, to mark this prestigious event. Watching them on parade, it is astonishing to see the uniformity of their drill and their uniform. The beautiful moment was ended with the Sikh platoon saluting and chanting delightful prayers. With the formal parade finished, all were assembled for the regimental photo with the Sergeant Major who had dedicated many an hour to train them to the high standards we bore witness to. As they posed for the picture, once again ‘Jo Bole So Nihaal, Sat Sri Akaal,’ reverberated around Old College. The Sergeant Major then gested, ‘I usually just say cheese!’ As laughter took over the seriousness of the event, it was plain to see how close a relationship had developed between the 30 Sikhs and the Sergeant Major.

This day was a very proud moment for loved ones to mark the history of those Sikhs who sacrificed their lives at the Battle of Saragarhi. This is the first event marking a new era of remembrance, which will mean that the sacrifice and bravery of the Sikh soldiers who fought for righteousness will not be forgotten.

Watch this space!

Help raise awareness for the Sikh soldiers whom fought with the British army in WW1 and WW2 . You can follow 1914 Sikhs on;

www.1914sikhs.org

Twitter - @1914Sikhs

Facebook – 1914Sikhs

Instagram – 1914Sikhs

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

1914 Sikhs Letter to an Unknown Soldier

Over centuries countless soldiers have died with their remains being identified. The Unknown Soldier has therefore become universally recognised as a description for those brave men who could not be afforded due recognition by fellow man yet remain “Known to God”

On the eve of the centenary of the outbreak of WW1 the 1418NOW - Letter to an Unknown Soldier campaign have initiated a remarkably powerful public initiative. Formed of thousands of letters from people expressing their thoughts, regrets, wishes, and blessings. The “Letter to an Unknown Soldier” will represent a living memorial to this immortal hero who transcends time.

The letter written by the 1914 Sikhs team on behalf of the Sikh nation to the Unknown Sikh Soldier is a humble effort to pay tribute to the Sikh Soldiers who we have allowed to be obscured from our individual and collective consciences.

We cannot begin to imagine how it must have felt to leave the plum and orange sunshine of the Punjab for the spectral black and white shadows of war. The cold trees that stood sentry over you as you lay waist-deep in mud and maggots, with only the death-tipped shooting stars for company as they spat holes in the velvet canvas of night. No helmet for you, honourable son, to protect you from the shells that whistled overhead. Instead you chose to fight and die with your turban, your faith intact amidst the shattered corpses.

Read the full letter here

Please share and even better still write your own message so that after 100 years we can lift the veil of anonymity and afford due credit to our forefathers.

www.1418now.org.uk

1 note

·

View note

Text

BBC World War One at Home

As I put pen to paper, I cannot describe in words the amazing weekend I have experienced in Wolverhampton’s fine location of West Park. I am genuinely very grateful to have been given the opportunity to take part in this phenomenal event!

The BBC’s World War One at Home event definitely attracted a lot of attention from the public, bringing in crowds from far and wide.

There were several stalls set up at Wolverhampton’s West Park, each telling the story of what life was like during the First World War. Each stall covered a uniquely different topic, such as; ‘Blood and Bugs’ which illustrated the development of blood groups and transfusions during the period of the Great War. The ‘BBC Bus’ gave the public a chance to become war reporters. The ‘Pigeon Parade’ left the public stunned with the use of pigeons to help aid the allied troops. The ‘War Communications Department’ covered the newspaper stories that launched in the time of 1914, from the ‘Women’s Right to Serve’ to the ‘Zeppelin Attacks’; giving families a chance to bond with their children and the opportunity to get involved, choose a news story alongside a headline, print it off and take away to keep. Learning Morse code was a challenging and exigent experience but once I got used to the sounds of the beeps, I couldn’t keep my hands off!

One stall which really caught my attention was that of the 1914 Sikhs Campaign. Seven members of the campaign were there to enlighten, entertain and inform the public of the contribution made by Sikh soldiers in the war effort. The public were very intrigued to learn about the bravery and sacrifices made by these fine warriors. The crowd at large was drawn to this fantastic, hard working and caring group of members of the 1914 Sikhs Campaign; individuals who were there to help everybody get involved. It was an eye opener for me being a Sikh myself in learning how soldiers from my own faith and nation were so courageous and never hesitant to support the greater cause of justice and liberty for all.

Caption: 1914 Sikhs volunteers with Dave from Frontline Living History

Despite little knowledge of the reasons behind the conflict, these Sikhs did not hesitate to take up arms to defend the freedom of Europe, leaving behind their own homeland to fight in defence of the homeland of another. Sikh soldiers were highly regarded by British officers for their martial prowess and never say die attitude, even today the British Army continues to hold Sikhs in high regard and utmost respect.

What astonished me the most was learning that although Sikhs only made up 2% of India’s population, Sikh soldiers made up 20% of the British Indian Army during the course of the war! Truly an incredible contribution when considering the size of their population.

One particularly interesting part of the 1914 Sikhs stall was seeing how onlookers were able to experience tying a genuine Sikh turban. For Sikhs, the turban symbolises honour, self respect, courage, spirituality and loyalty whilst also serving as protection for the head during war. Historians mention how during the period of the Great War, Sikh soldiers would be seen picking out bullets from their turbans after battle.

Highlights from the BBC World War One at Home Live Event in Wolverhampton's West Park

It was very inspiring seeing these young Sikhs coming together to honour their forefathers who fought alongside Britain.

The number of members in the group are growing, with the youngest being just 15 years of age. When speaking with the youngest volunteer, Onkar Singh from Birmingham, how it felt to be part of the project despite studying at school, his response was;

‘I really enjoy being a part of this project. I have learnt so much about how our soldiers fought and I am still learning. In school they don’t teach about the contributions made by foreign soldiers so it’s nice to see that someone has taken on this initiative. We have been involved in many events and hope to continue doing many more. It really is like one huge family, my uncle is part of the team and the rest of the guys are all like older brothers to me. You can’t really put into words the love and respect that all the guys have for each other and the commitment they share in keeping the memory of our forefathers alive! I enjoy capturing priceless moments which is why I was asked to join the team as one of the team's photographers.’

Had it not been for the 1914 Sikhs team I may never have gained the valuable knowledge that I did that day. I felt the hard work and positive vibe that was surrounding the team. They were all very friendly, always smiling and laughing; and certainly made me feel welcome with their loving attitude and all that banter of getting each other’s name correct! When I first arrived to see the 1914 Sikhs stall, I was a stranger to all of the guys, but in all honesty, after only a few short minutes, it felt like I had known them all for a lifetime.

In all, the BBC World War One at Home event was a huge success! All ages and communities were welcomed with open arms. It was definitely heart warming to listen to the elder generation speak about their grandparents being involved in the Great War and to see the younger generation keeping their legacy alive. The public, BBC team and the volunteers; including myself were surely left feeling inspired and grateful.

Help raise awareness for the Sikh soldiers who fought with the British army in the First World War.

View more pictures from the event here:

https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.250229931768011.1073741831.217347435056261&type=1

For further information please contact:

Contributing Editor, Baljit Kaur at [email protected]

1 note

·

View note

Text

Foreign soldiers who fought trenches with the Tommies must not be forgotten, Cabinet minister says

Britain must remember the "Tariqs and Tajinders" as well as the "Tommies" who fought, and in many cases died, in the First World War Baroness Warsi warns.

Cabinet Minister Baroness Warsi Photo: GETTY IMAGES

Foreign troops who fought alongside British soldiers in the First World War must not be forgotten, a cabinet minister will say.

Britain must show its gratitude to the "Tariqs and Tajinders" who fought with the “Tommies in the trenches" for the hardships and horrors endured in a war fought thousands of miles from their homes, Lady Warsi will say.

The soldiers, sailors and airmen from the Commonwealth played in The First World War. More than 70,000 soldiers from the British Indian Army alone lost their lives during the conflict. Over 100,000 Canadians and Australians died in battle.

In 1915 the British Army formed a West Indies regiment to accommodate the15,000 Caribbean volunteers who had made their way to Britain to fight in the war.

Unveiling commemoration plaques to the bravest of these foreign soldiers Lady Warsi will stress that without the support of these foreign fighters Britain and the Allies would “not have prevailed”.

Around three million men from across the Commonwealth signed up to fight alongside British soldiers during the four years of war, with some travelling at their own expense from places as fair flung as Africa and the Caribbean to join the allied cause.

175 of these acted with such conspicuous bravery, self-sacrifice or extreme devotion that they were awarded the Victoria Cross, Britain’s highest military honour.

Soldiers from Canada, Australia and India as well as Belgium and Ukraine are among those who were honoured.

The plaques to each soldier who received a VC will now be sent to each soldier’s country of origin to be permanently displayed in public places.

As part of the commemoration of the centenary of WWI, the Foreign Office will be publishing an online digital archive of all the overseas VC recipients.

Lady Warsi will tell the event at Lancaster House in Westminster: “The bugle call to arms that sounded across Britain in August 1914 carried to the farthest corners of the world … and around three million men responded, coming to Britain’s aid and joining the Allied cause.

“Tariqs and Tajnders fought shoulder to should with Tommies in Flanders, Ypres, Gallipoli and Passchendele.

“And it is very clear without all of them Britain, the Allies, could not have prevailed. Without them we would not have the rights and freedoms that we all enjoy today.”

Among the recipients was Gobind Singh from India, awarded the VC after he saved fellow soldiers on three occasions by walking miles under heavy fire to deliver messages, after his horse was shot from under him.

Last year Lady Warsi visited the battlefields of France and Belgium on her “own personal pilgrimage visiting to the Neuve Chapelle India Memorial and laid a wreath to Sikh soldiers in Hollobeke in Belgium.

She added: “All deserve our enduring gratitude and respect for the hardships and horrors they endured, and for the selfless sacrifice they made. To me they are all heroes.”

Her words come as David Cameron travels to Ypres, Belgium to meet EU leaders for a summit two days before the 100th anniversary of the killing in Sarajevo of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the event regarded as the trigger for war.

The summit will begin at the Menin Gate, the memorial bearing the names of more than 54,000 soldiers from Britain, Australia, Canada, India and South Africa who have no known grave.

Among the names on the gate is that of Captain John Geddes, a relative of the Prime Minister who died at Ypres in 1915 in a clash known as the battle of Kitchener’s Wood.

Source: www.telegraph.co.uk

0 notes

Text

The men who cut the war short

Caption: Indian infantrymen on the march in France during World War I. Photo: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Gordon Corrigan was a soldier in the British army’s Royal Gurkha Rifles before embarking on a career as a historian and broadcaster. In 1999, he published Sepoys In The Trenches: The Indian Corps On The Western Front 1914-15, a detailed account of the Indian involvement and presence during the actions in France and Belgium. We spoke to Corrigan about the experiences of the Indian soldiers and their overall impact on the war. Edited excerpts:

What was an average day in the trenches like for a sepoy?

The average day in the trenches for Indian Army troops was very similar to that for British soldiers, except that Indian soldiers spent rather more of them. An Indian Army battalion was smaller than a British one at war establishment (753, all ranks, as compared to 997) so an Indian division had around 2,000 less infantrymen than a British division, but was expected to hold the same length of front.

This meant that rotation of men and units through firing line, support line and reserve line was less frequent for Indian units. A typical day would start with “stand to” half an hour before first light when every man was on the fire step, kit on and weapon ready to fire. This lasted for an hour and was a long-standing custom, originally because attacks tended to come in at first light and/or last light (when there was another “stand to”), but it gave platoon havildars, and platoon and company commanders, a chance to go round their men and see that all was well.

After that breakfast (usually tea and a chapati) would be brought up through the communication trenches carried by followers. Unlike in the British army, where tasks such as cooking, latrine cleaning, fetching and carrying were carried out by soldiers, in the Indian Army they were done by followers, civilians who were not paid a great deal but many of whom had served their regiments for generations, and did of course allow soldiers to get on with the business of fighting.

There are numerous tales of British officers’ followers going to extraordinary lengths to find bacon (the French don’t do bacon) and eggs for their sahebs. The rest of the day would be spent improving the trenches, repairing the revetting and the wire, resting and sleeping, and being briefed for night patrols into no-man’s land.

Lunch and dinner would be rice, chapatis, meat for meat-eaters (goat, mutton or chicken) and vegetables, washed down with large quantities of tea. A popular item was the rum ration—one tablespoonful of rum (diluted one part of rum to six parts of water) per man per day. It was insufficient to affect the man’s reactions, but a morale booster nevertheless.

Meals were eaten by half sections, that is, one half would eat while the other half remained alert, and weapon cleaning each day would also be done by half sections so that there would always be weapons that were assembled and capable of being fired. Much work was done by night so men usually slept during the day, provided they were not being attacked or shelled.

Under cover of darkness, patrols would go out to dominate no-man’s land, raids on enemy trenches would be carried out, communication and fire trenches would be extended and ammunition and trench stores carried up from the rear. Indian soldiers might be in the firing line for up to five days at a time (up to seven in early 1914) before being relieved. There would be long periods of boredom when nothing much was happening, brief moments of sheer terror when being shelled or, more so, when a mine was set off under a trench, and times of pure exhilaration as the adrenalin kicked in when they were attacked or were attacking.

How well did the soldiers and their British officers get along?

Gordon Corrigan. Having interviewed many ex- sepoys and ex British officers of the Indian Army (albeit most from World War II, although a few from World War I too), read many personal accounts and in my own experience of 30 years with the Gurkhas, there is no doubt that a very strong bond existed between the British officer and the Indian soldier.

Of course the Indian soldier had to move some way towards the requirements of a modern Western and technological society, but the British officer was required to make a much greater move. He had to learn the language and be fluent in it, he had to understand the religion and culture of his soldiers and to conform to them (I, a Christian, have probably spent more time attending religious ceremonies in Hindu and Buddhist temples than I have in churches) and was required to trek in his soldiers’ homeland when on leave of absence (the exception was Nepal, a closed country until 1956).

Sikhs regard tobacco with abhorrence, so British officers in Sikh battalions were non-smokers in an age when just about everybody smoked. The bond was stronger, strangely perhaps, than it was between a British soldier and his officer, perhaps because there was no perceived class or social difference, rather Indian units were very much a “band of brothers”, with the British commander being the father (even if he was very young).

Today we pay great attention to cultural diversity and a multi-racial society—the old Indian Army was exactly that, with the British being just one more race among the many (admittedly the British were in command, but the analogy is relevant nevertheless). What the Indian Army brought to the front was an ability to improvise—the British army had no trench mortars in 1914 so the Indian sappers and miners made some initially from wood bound with wire and then from steel tubing. They made improvised hand grenades when no factory-produced model was available. All this came from soldiering in inhospitable areas (like the North-West Frontier) where, if something was unobtainable and you couldn’t find it, you simply made it.

You’ve written about the western front in your book. But what about the other theatres?

How important were the Indians? General Ian Hamilton thought that if he had had more Indian Army units at Gallipoli he would never have been held up by the Turks. The only people who knew what they were doing at Gallipoli were the units of 29 Indian Infantry Brigade (at various times two Punjabi battalions, one Sikh battalion and four Gurkha battalions), but there were no more Indian Army units to send, they being heavily engaged elsewhere.

Moving the Indian Corps to Mesopotamia in late 1915 made sense as they were better able to cope with the climate and the terrain than British troops, and by then there were enough British and empire troops available for the western front. Palestine could not have been conquered without the Indian Army (and the Australians) and the Suez Canal could not have been held without the Indians.

Were the sepoys held in high regard by the enemy?

The Germans were well aware of the abilities of Indian troops and were frightened by them, sometimes going to extraordinary lengths to surrender to British soldiers rather than Indians. There were rumours that Indians took no prisoners (untrue), that they ate prisoners (even more untrue) and that they used expanding bullets (illegal under the Hague Convention and also untrue).

Overall, when you look at the Indian contribution in totality, how much of an impact did they really have?

Indian and other empire troops made a huge difference to the outcome of the war.

By 1918, the BEF (British Expeditionary Force) had 50 British divisions and 12 empire divisions on the western front, with Mesopotamia and Palestine mainly being left to empire troops. In 1914, the Indian Corps arrived in France in just enough numbers and just in time to plug the gaps around the Ypres Salient.

Had they not been able to do so, the Germans might well have been able to break through, in which case the French would have withdrawn to protect Paris and the British would have evacuated Europe. Germany would probably still have lost the war as long as France was not defeated, which was by no means a certainty. And the Royal Navy blockade would have starved the Germans out eventually. But without that timely injection of Indian troops, the war in the west would have lasted far, far longer.

It must have been quite a culture shock for many of the soldiers. Tell us a few of your favourite Indian Army anecdotes from the war.

Firstly there is the story of Rifleman Gane Gurung, 2/3rd Gurkha Rifles, at Neuve Chapelle. A British advance was held up by a house in the middle of the village which was fortified and strongly held by German infantry. Without orders, and in an example of suicidal stupidity (and bravery), Gane alone ran across the square and burst through the front door. Everyone assumed he would shortly be dead.

There was much shooting and shouting, then silence. The front door opened and out came a file of seven large Germans, hands in the air, followed by a 5ft, 2 inches Gane with rifle and bayonet. The village was captured shortly afterwards.

Then, at Orleans, Sikh battalions, seeing the statue of Joan of Arc, assumed she was a goddess of the goras and took to saluting her as they passed.

Finally a German officer in a dugout, when the Indians attacked at Neuve Chapelle, found himself on the wrong side of the line when the battle ended, and came out to surrender. He was found, in full uniform, by the military police 3 miles away. Asked what he was doing he said that the area was full of Gurkhas who all saluted him! At this stage of the war, neither side was totally correct in matters of uniform so the chap being a gora was assumed to be British or French.

Source: www.livemint.com

0 notes

Text

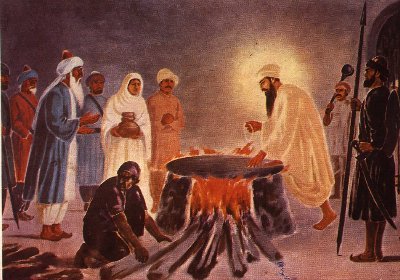

Shaheedi. Martyrdom. Sacrifice.

The ability to selflessly give one's own life for the sake of protecting the life of another.

A spirit of true love and compassion, instilled within the people of the Sikh Faith through the sacrifice of Guru Arjan Dev Ji, the fifth Guru of the Sikhs.

Caption: Guru Arjan Dev Ji, the fifth Guru of the Sikhs about to attain martyrdom as he sits on a hot iron plate to have boiling sand poured over his body.

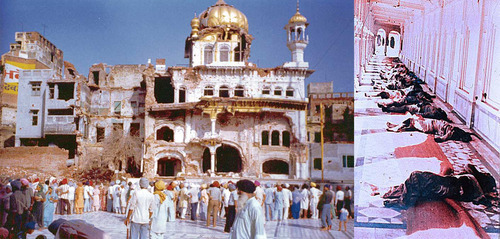

The month of June represents a very solemn time for many communities. As the Chinese remember those who were massacred at Tiananmen Square, as the Armenians remember those of their community who were brutally killed in the Armenian Genocide, the Sikhs reflect on the beginning of a systematic genocide of the Sikh people within India which even today manifests itself in forms of oppression and discrimination.

Caption: Tank Man. The iconic image of a lone unarmed man preventing armoured tanks from passing came to represent the bloody crackdown on peaceful protesters.

Caption: Armenian civilians, escorted by armed Ottoman soldiers, are marched through Harput (Kharpert), to a prison in the nearby Mezireh.

With the storming of the Akal Takht, the temporal throne of the Sikh Nation and the holiest shrine of the Sikh Faith, thousands of innocent men, women and children were brutally killed at the hands of the Indian Armed Forces in an attempt by the Indian Government to ethnically cleanse the people of Panjab.

Caption: Left, damage of Akal Takht from the attacks in 1984. Right, Innocent pilgrims lay dead after being shot at point blank range.

The time of June also marks the Battle of Krithia, Gallipoli, where the 14th Firozpur Sikhs suffered high casualties whilst fighting for the freedom of Europe during the First World War.

Whether it be the sacrifices made by Guru Arjan Dev Ji and his Sikhs in standing up to fight the tyrannical Mughal Empire. Whether it be the sacrifices made by the Sikhs in standing up to fight the oppressive British Raaj within India or the Sikh regiments fighting against the brutal powers of Europe during the World War. Whether it be the Sikhs who stood up and still continue to stand up and fight against the injustices carried out by the Indian Government...we salute you all!

'Jabai Ban Lagaiyo Tabai Ros Jagaiyo.' 'When the arrow hit me then I became enraged.'

- Guru Gobind Singh Ji, The 10th Guru of the Sikhs - Amrit Keertan, Ang 297

#1984#sikhs#armenian#armenian genocide#Tiananmen Square#golden temple#massacre#gallipoli#sikh genocide

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

To show their contempt for death, some Sikhs had refused to hide in the trenches

Sikh soldiers on the march in France at the start of the first world war. Photograph: Hulton Archive

12 Nov 1914: When the Indians Arrived

The people of the Raj – modern India and Pakistan – were not consulted about their participation in the war. More than 1 million soldiers served overseas in the Indian army – and 75,000 died. By autumn 1914, Indians were on the western front.

It was a curious sight to all of us, French or English, the day when the Indians arrived in a dreary little town of Northern France … Suddenly the Indian Lancers appeared, and the pavement on both sides of the street was at once filled by a crowd of soldiers and civilians watching the procession, as a London crowd will do in Whitehall on the day of the opening of Parliament. In fact, those Indians looked all like kings. The Lancers sat proudly in their saddles, with their heads upright under the Oriental crowns; then came a regiment of Sikhs, walking at a brisk pace, all big and strong men, with curled beards and the wide 'pagri' round the ears; the Pathans followed, carrying on their heads that queer pointed bonnet, the 'kullah,' which reminds one of the warriors seen on old Persian tapestries – a more slender type of men, but equally determined, and with faces at the same time smiling and resolute.

… The day after, we heard that during the night one of the Sikh regiment had had to recapture the trench, which the Germans had taken by surprise, and that their bayonet charge was so tremendous that the enemy did not dare counter-attack. Almost immediately after that feat an order came not to allow the Indians uselessly to expose their lives by walking out of the trenches. The fact was that, in order to show their contempt for death, some Sikhs had refused to hide themselves in the trenches and had immediately drawn a fierce fire on their regiment. Fortunately, they did not insist on playing that sort of game; otherwise the Indian Army Corps would have disappeared in one week's time out of sheer bravery. […]

A 'Black Maria' fell quite near a sapper while he was lying on the ground and steadily firing on the advancing foe. It did not hurt him, but dug a hole six feet deep at his side. The sapper – a Sikh, I believe – waited until the smoke had gone, and then jumped into the hole. He soon found that the position was a comfortable one, and started firing from the cover the Germans had dug for him; according to officers who were standing by, he managed to kill some fifteen or twenty Germans by himself, and would have remained there for ever if he had not been eventually ordered to retreat. He was warmly congratulated afterwards, but did not appear to think he had done anything remarkable.

December 1914: A British Officer's Letter

A truce had been arranged [on Christmas Day] for the few hours of daylight for the burial of the dead on both sides who had been lying out in the open since the fierce night-fighting of a week earlier. When I got out I found a large crowd of officers and men, English and German, grouped around the bodies, which had already been gathered together and laid out in rows.

I went along those dreadful ranks and scanned the faces, fearing at every step in recognise one I knew. It was a ghastly sight. They lay stiffly in contorted attitudes, dirty with frozen mud and powdered with rime.

The digging parties were already busy on the two big common graves, but the ground was hard and the work slow and laborious … we chatted with the Germans, most of whom were quite affable, if one could not exactly call them friendly, which indeed, was neither to be expected nor desired. […]

They spoke of a bottle of champagne. We raised our wistful eyes in hopeless longing. They expressed astonishment and said how pleased they would have been, had they only known to have sent to Lille for some. "A charming town, Lille. Do you know it?" "Not yet," we assured them. Their laughter was quite frank that time.

Meanwhile time drew on, and it was obvious that the burying would not be half finished with the expiration of the armistice agreed upon, so we decided to renew it the following morning.

On Boxing Day … we turned out again … The German soldiers seemed a good-tempered amiable lot, mostly peasants from the look of them. One remarkable exception, who wore the Iron Cross and addressed us in slow but faultless English, told us he was Professor of early German and English dialects at a Westphalian university.

He had a wonderfully fine head … The digging completed, the shallow graves were filled in, and the German officers remained to pay their tribute of respect while our chaplain read a short service.

It was one of the most impressive things I have ever witnessed.

Soldiers wearing gas masks repair telephone lines during a gas attack. The use of gas as a military weapon was widespread during the first world war. Photograph: Corbis

Friend and foe stood side by side, bare-headed, watching the tall, grave figure of the padre outlined against the frosty landscape as he blessed the poor broken bodies at his feet. Then, with more formal salutes, we turned and made our way back to our respective ruts.

7 May 1915: The Gas Atrocity in Flanders

The following extracts from a letter written by a British officer at the front speak of the terrible suffering of soldiers who were "gassed" during the Germans assaults on Hill 60: "Yesterday and the day before I went with *** to see some of the men in hospital at *** who were 'gassed' yesterday and the day before on Hill 60. The whole of England and the civilised world ought to have the truth fully brought before them in vivid detail, and not wrapped up, as at present. When we got to the hospital we had no difficulty finding out in which ward the men were, as the noise of the poor devils trying to get breath was sufficient to direct us.

"We were met by a doctor belonging to our division who took us into the ward. There were about twenty of the worst cases in the ward on mattresses, all more or less in a sitting position, propped up against the walls.

"Their faces, arms, and hands were of a shiny grey-black colour, mouth open and lead-glazed eyes; all swaying slightly backwards and forwards trying to get breath. It was the most appalling sight, all those poor black faces struggling for life. What with the groaning and the noise of the efforts for breath, Colonel ***, who as everybody knows, has had as wide an experience as anyone all over the savage parts of Africa, told me to-day that he never felt so sick as he did after the scene.

"In these cases, there is practically nothing to be done for them, except to give them salt and water to try and make them sick. The effect the gas has is to fill the lungs with a watery, frothy matter, which gradually increases till it fills up the whole lungs and clogs up the mouth; then they die. It is suffocation – slow drowning – taking, in some cases, one or two days. Eight died last night of the twenty I saw, and most of the others I saw will die, while those who get over the gas invariably develop acute pneumonia.

"It is without a doubt, the most awful form of scientific torture. Not one of the men I saw in hospital had a scratch or a wound.

The Battle of Arras in April 1917 Underground, soldiers took shelter in tunnels dug centuries earlier by rich merchants. Photograph: Hulton Archive

"The nurses and doctors were all working their utmost against this terror, but one could see from the tension of their nerves that it was like fighting a hidden danger which was overtaking everyone.

"A German prisoner was caught with a respirator in his pocket. The pad was analysed, and found to contain hypo-sulphite of soda with one per cent of some other substance. The gas is in a cylinder, from which, when they send it out, it is propelled a distance of 100 yards. It then spreads. English people, men and women, ought to know exactly what it going on."

13 April 1917 : In the Caves of Arras

"This is King Street," said a voice in the darkness to-day, "the third to the left is India Lane." A moment later I collided violently with a dark figure, moist with mud, and our steel helmets rang sharply. We were in the caves of Arras, tunnelled out centuries ago, when rich merchants built the houses in the Grande Place and mansions guarded within grand walls, all pierced now or quite destroyed by two years of German shell-fire. But the caves and the tunnels have not been touched by any shell. They are very deep and wander in a maze far below the ruins of the cathedral city and out in the open country.

On Sunday night last, before our advance across the German lines, thousands of our soldiers waited in these caves for dawn, and before the dawn, marched down the tunnels, pressed close in a long tide of life, streaming forward for an affair of death. Hour after hour the supporting troops followed the first waves of assault, and from the world above came down the first of the wounded.

They passed their comrades closely, touched them with the blood of their wounds, and steel helmets clanked together. There was not much talking. The men going up asked a question or two. "How's it going, mate?"

"'Fine; we're through the second line."

"Badly hit?"

"It hurts, but it ain't much, old lad."

The long tunnel was only dark at its entrance. Further along was the glimmer of electric bulbs, set along the walls at even distances. I passed on a long way and heard a throbbing down in a deep pit and felt a sudden warmth come up to me. Here was the power-house for the electric plant. Further still I looked down other tunnels leading away to unknown places. Men slouched down them and talked in low voices. Cigarette-ends glimmered, a rifle fell with a clatter. I had a sense of bring in a subterranean world inhabited by men doing uncanny work. […]

I turned down India Lane, climbed a long flight of chalk stairs, felt the wind blow on my face, and heard the infernal clangour of great guns. My steel helmet caught in a strand of barbed wire. Before one stretched the battlefields of Arras. Down across the battlefields came the walking wounded. They were not in a company, which makes suffering more tolerable … but in single figures, lonely, after being hit by chance shells up by a village where fighting was then in progress.

I hated to pass these men without an offer of help, but I could do nothing for them. They walked very slowly, avoiding the litter of brickwork flung up by shell-fire, drawing breath sharply when their tired feet stumbled against a stone, hesitating with a look of despair when they came to the edge of broken trenches. They were "light cases" – the lucky ones – but their way was a Via Dolorosa.

An officer came along in a private's tunic. He was wounded in the arm and very white and weak looking. "Feel bad?" I asked. He smiled. "I'm all right … but it's slow going."

A comrade with me pulled out a flask and said, "This will do you good." The officer lifted it to his lips, and the colour came back into his face a moment. "Thanks very much," he said, "elixir vitae at a time like this." A German crump cracked a score of yards away from us with a howl and a roar. The wounded officer struck half right. "Not out of it yet," he said. I watched him stagger a little and then straighten himself and trudge on – a gallant man, needing all his courage for that walk.

The German prisoners huddled together for warmth until they were given shelter. The officers were … grateful for their treatment and were polite to their captors, saluting punctiliously with a click of heels. They were mostly young men and not professional soldiers before the war, and nearly all of them Bavarians and Hamburgers.

Some of them excused themselves for being unshaven and dirty.

"We had to keep close to the dug-outs," they explained. "Your drum fire was frightful. Up above it was certain death."

"The waiting was worse than death," said one young officer whose hand trembles as he lit a cigarette. […]

"We could do nothing. We were trapped," said the Brigadier, who was taken with his whole staff. The Brigadier wept a little. He confessed to the humiliation of being captured with such little loss among his men. "We thought the Vimy Ridge impregnable," he said.

But his greatest grief was not for the defeat or for the capture or sufferings of his men. "My little dog," he said again and again. "Has anyone seen my little dog? It has been with me ever since the beginning of the war." He had lost his little dog when he had come out of his dug-out and held up his hands and then come down with his mob of men.

9 October 1917: A Country Diary

The barometer was falling at the weekend, and yet on Saturday the sun and wind combined to make an ideal day for fruit-getting. Many worked, as we did, from early morning till dusk. Since the storms of wind and rain have swept over the country … I find from very recent inquiries that farmers in Cumberland and Westmorland have come through their labour difficulties exceedingly well, owing to the ready help given them by their friends and neighbours in all ranks of society. To see a lady of title drive a milk cart and at a pinch shoe her own horse, and young and old take their share of the work, rough or smooth, as they have done now for months past, shows one that there is no degeneration in the race.

Source: www.guardian.co.uk

0 notes

Text

Walking the Western Front: A Sikh soldier lies at rest, far from homeland and adopted land

He left no photos, no letters, but Sunta Gouger Singh was among 10 Sikh soldiers who fought with Canada in the Great War. And he was the first to give his life

Image: Richard Lautens/Toronto Star

La Laiterie military cemetery outside Ypres.

Kemmel — Sunta Gouger Singh was the first Sikh to die for Canada in the Great War, but his headstone in a rural cemetery outside Ypres is the only Canadian one without a maple leaf engraved on it.

At the outset of the war, most of the men who enlisted were immigrants — most obviously the British who felt a strong tie to the homeland. But there were people from many backgrounds, both new and old to Canada. Among them were 10 Sikhs.

The Sikh population in Canada was small at the outset of WWI, dropping from 5,000 in 1907 to fewer than a couple of thousand by wartime, largely because restrictions, including the head tax, made immigration difficult. Those who were successful usually landed in Vancouver, though many were turned away — most famously, the ship Komagata Maru was denied entry into Vancouver in 1914 because of exclusion laws.

Singh was born in Lahore, Punjab, India, in 1881 and signed up for service in Montreal. On his attestation papers, “complexion” has been crossed out and a word that looks like “caste” is written in its place: “Rugepoot. E. Indian,” which is perhaps a bungled interpretation of a Sikh Rajput.

“The Sikh community has had a long-standing military tradition,” says Pardeep Singh Nagra, the executive director of Sikh Heritage Museum of Canada, noting that photos of early Sikh pioneers in Canada show them wearing military medals. One interesting stat: Sikhs made up 22 per cent of India’s armed forces at the outset of the war although they accounted for less than 2 per cent of the population. Singh had been a member of the Punjab Rifles for three years before he came to Canada.

Image: Richard Lautens/Toronto Star

Gouger Singh's name is given many alternate spellings on a variety of official documents, including his gravestone.

La Laiterie Cemetery is a regimental cemetery; many men buried here were “trench wastage” — a term common in WWI to refer to a soldier killed by a sniper or a shell but not in a major offensive.

Singh’s grave is in the area farthest from the road, under a copse of trees, on the sloping land where the 24th battalion (Victoria Rifles) buried their men.

According to the battalion diary, they finished their tour of nearby trenches on Oct. 4, 1915, with an enemy that was fairly active with “sniping and artillery.” Just beside Singh’s final resting place, headstones marked W.A. Ward, E.A. Clift, mark the human toll of the diary’s neutral language.

On Oct. 13, the men bombarded the enemy’s line and threw smoke bombs. T.G. Smith, buried to Singh’s right, died that day.

On Oct. 16, the battalion was relieved: “Our second tour of duty in the trenches, apart from the bombardment was an uneventful one,” the diary notes. The graveyard and the luxury of hindsight tell another story: six Canadians buried.

While they were resting in billets, working parties were sent to rebuild trenches, day and night. Singh was likely involved in this work; he was killed in action on Oct. 19.

The bureaucracy wasn’t sure how to classify Singh in life or death. On the enlistment papers he belongs to the Church of England, on a death certificate he is Buddhist. At the cemetery, he is listed under “Gougersing” in the registry. His headstone — which spells his name Gougar instead of Gouger — is engraved with Gurmukhi (the most common Punjabi script) that translates as “God is one” and “Victory to God.”

Of the three Sikh Canadian WWI graves, two have maple leafs and one has a cross. Nagra isn’t sure why Singh doesn’t have a maple leaf but believes it might be related to the script, which overlaps the area where the maple leaf usually goes.

Image courtesy of the Sikh Heritage Museum of Canada

Indian troops in the British Army.

There are no photos of Singh, no letters. The museum does have a letter from Sikh Waryam Singh, describing fighting on the Somme in November 1916, where shells and bullets fell like rain and “one’s body trembled to see what was going on.”

“We went over like men walking in a procession at a fair and shouting we seized the trench and took the enemy prisoners. I didn’t think of our safety at all but felt that the Guru Maharaj was fighting in me. He is great and it is thanks to Him that I was able to do all I did … The bravery which we showed that day was the admiration of the British soldiers. After the fight they asked me how it was that I was so utterly regardless of danger,” he wrote.

There is only one name in the visitor book of this cemetery — Mrs. P. Jackson, April 19, 2014, from Carperby North Yorkshire. “Beautifully kept,” she writes.

Leaving the cemetery, the highest peak in Flanders (it is generously called Mount Kemmel, though just 156 metres) was a valued strategic prize in wartime. On the way to the top, past the bunkers where British forces were able to observe nearby Ypres and Messines, a grouse squawks and bursts out of the roadside bramble, the effect a cartoonish explosion.

Up the steep incline is the French ossuary honouring the soldiers who died here in April 1918 when the Germans finally broke through.

At a nearby hotel, we are given a room with a view. The man at the front desk says he’d do the same for anyone, from any country. Maybe not Germany, he says, smiling. They did take this place twice.

And as photographer Richard Lauten chimes in, on those occasions they didn’t make a reservation.

Source: www.thestar.com

1 note

·

View note

Text

1914 Sikhs & Satinder Sartaaj

Londons' Royal Albert Hall was the scene for the final leg of Mehfil-e-Sartaaj, and what a fine setting it was for the finale of a sell out tour.

Eager fans packed into the historic venue for what was sure to be an evening showcasing the finest of Punjabi musical artistry. 1914 Sikhs ambassadors were alongside decorated Sikh veterans, on what was to become an unforgettable night.

With the stage set, and the lights dimmed, the crowd roared with delight as BBC presenters Bobby Friction and Suzi Mann announced "Sartaaj, Sartaaj, Sartaaj". In a truly modest and thoughtful walk onto the stage, Sartaaj greeted all in the traditional Punjabi way. Finally taking his seat amongst his musicians, crossed legged on the floor of the stage, he opened up his harmonium, his book of poetic music, and the audiences' hearts.

As the night proceeded, the air was filled with the hypnotic sound of harmonium, tabla, bansuri and violin. The energy was palpable, and the audience mesmerized. For the 1914 Sikhs team, it was a unique opportunity to spend the evening in the company of our guest Sikh war veterans. We wanted to share this opportunity with everyone, so at the interval, ushered backstage, we prepared ourselves to announce the 1914 Sikhs campaign to all at the Albert Hall.

Bobby Friction set the scene by referring to the centenary of World War 1 and paying tribute to all those from the Indian sub continent who had given their lives. The crowd rose to their feet in unison, cheering and applauding as the small band of Sikh ex-servicemen presented Satinder Sartaj with a memento on behalf of the 1914 Sikhs campaign. The pride and heartfelt emotion exuding from everyone in the venue was both moving and inspiring.

Caption: From left to right, 1914 Sikhs ambassadors, Amritpal Singh & Danash Singh along with World War Veterans, Sardar Smittar Singh, Sardar Rajinder Singh & Sardar Mukhtar Singh, presenting 1914 Sikhs artwork to Satinder Sartaaj at the Royal Albert Hall, London.

0 notes

Quote

As a wounded Sikh wrote to his brother: "I must finish my letter... In a few days I shall go back to the war... If I live, I will write again" Some men even seemed to sense that their letters might even become their memorial.

Indian Voices of the Great War. David Omissi.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

1914 Sikhs - Never Fogotten

1 note

·

View note