#calixtus iii

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

October 14th 1285 saw the second marriage of King Alexander III to Yolanda de Dreux.

We hear a lot about Alexander in my posts due to the events after his death, I will try and concentrate more on his Queen, although she was Scotland’s Queen Consort for only 4 months and 14 days.

In that short time, Yolanda carried the hope of a nation – and its king – to secure the Scottish succession.

Yolande was born into a minor branch of the French royal family, probably sometime in the mid-1260s. Her father was Robert IV, Count of Dreux, who died in 1282 and her mother was Beatrice de Montfort, who died in 1311. She had 2 brothers and 3 sisters. Little is known of Yolande’s childhood but we can imagine that as a junior member of the Capetian dynasty, she grew up amidst some privilege and splendour.

Queen Margaret died in 1275 and within 8 years all 3 of her children were dead; 8-year-old David died at Stirling Castle at the end of June 1281, Margaret died in childbirth on 9th April 1283 and Alexander died at Lindores Abbey in January 1284, sometime around his 20th birthday. Alexander’s heir was now his infant granddaughter by Margaret and Erik, little Margaret, the Maid of Norway, born shortly before her mother’s death.

Whilst Yolande was growing into adulthood Scotland was experiencing a “golden age”, a period of relative peace and prosperity. Her king, Alexander III was married to Margaret, daughter of Henry III of England and the couple had 3 children survive childhood. Their daughter, Margaret, born at Windsor on 28th February, 1261, was married to Erik II, king of Norway, in August 1281. Their eldest son, Alexander, was born on 21st January 1264, at Jedburgh. On 15th November 1282 Alexander married Margaret, the daughter of Guy de Dampierre, Count of Flanders. A younger son, David was born on 20th March 1273. With his entire dynasty resting on the life of his toddler granddaughter, Alexander started the search for a new wife. In February 1285 he sent a Scottish embassy to France for this sole purpose. Their successful search saw Yolande arrive in Scotland that same summer, accompanied by her brother John. Alexander and Yolande were married at Jedburgh Abbey, Roxburghshire, on 14th October 1285, the feast of St Calixtus, in front of a large congregation made up of Scottish and French nobles. Yolande was probably no more than 22 years of age, while Alexander was in his 44th year.

The marriage was the shortest of any English or Scottish king, lasting less than 5 months. Tragedy struck in March of 1286 when Alexander took a tumble down that cliff near Kinghorn.

There followed months of uncertainty in Scotland. She had lost one of her most successful kings and the succession was in turmoil. Little Margaret, the Maid of Norway, had been recognised by the council as Alexander’s heir, but his queen was pregnant; and if she gave birth to a boy he would be king from his first breath. A regency council was established to rule until the queen gave birth. In the event, Yolande either suffered a miscarriage, or the child was stillborn. Some sources, the Lanercost Chronicle in particular, have questioned whether Yolande was pregnant at all, suggesting that she was intending to pass off another woman’s baby as her own. The plan thwarted, the chronicle recorded that ‘women’s cunning always turns toward a wretched outcome‘.¹ However, there are major discrepancies in the chronicle’s apparently malicious account and tradition has the baby buried at Cambuskenneth.

In May 1294 Yolande had married for a second time; Arthur of Brittany was a similar age to Yolande and was the son and heir of Jean II, duke of Brittany and earl of Richmond. Yolande was the second wife of Arthur, who already had 3 sons, Jean, Guy and Peter, by his first wife, Marie, Vicomtesse de Limoges.Yolande and Arthur had 6 children together.

Her second husband died in 1345 and after being widowed for a second time Yolande did not remarry.

During her time in Brittany Yolande continued to administer her Scottish estates; in October 1323 safe-conduct to Scotland was granted to a French knight ‘for the dower of the Duchess of Brittany while she was Queen of Scotland‘.

It seems uncertain when Yolande died. Sources vary between 1324 and 1330, although she was still alive on 1st February 1324 when she made provision for the support of her daughter, Marie, who had become a nun.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝟓 𝐒𝐎𝐍𝐆𝐒 𝐑𝐄𝐌𝐈𝐍𝐃𝐈𝐍𝐆 𝐎𝐅 𝐘𝐎𝐔𝐑 𝐌𝐔𝐒𝐄

Calista, the Immortal.

A collection of classical and metal music, symbolizing the key moments of Calista's lore and life along with pieces of her thoughts.

i - Isle of Wight - The Witch.

Princess Ui Sun of the Joseon Dinasty, in the 14th century. Revoked times when she was still human, before she turns into Calista, the monster.

"My beauty is praised, from the core of the Mountains to the edge of Meadow, in dawns and sunsets. Lines and Pools of Begging Souls, Empty Hearts and Unknown Faces I despise the carnation of. They bow at my feet, cover me in presents I did not request for. My name at the tip of their tongue rolls carefully yet, is carelessly thrown in some foolish adoration and a weak submission. This beauty of mine became theirs by simply praying to it, buying it. Princess Ui Sun, Soon to become Queen of the Qing Dinasty. A title I did not wish for."

ii - Hall Of The Mountain King - Apocalyptica.

The Lamia awakening, after a ritual performed by the Witches of Sihege. Princess Ui Sun is no more, only the beast remains. Calixtus Orion aka Calista, Daughter of Hecate, the Lamia, is born.

"What have they done to me? I have it. The hunger for blood and flesh, I crave it, I kill for it. It torns my limbs, twists my organs, overwhelms my senses, obsesses my mind and I crawl, I crawl like a serpent, like a beast in the night, in the forest, in the dark. I seize it, my first, second, hundredth prey and I feast. Bones cracking under my claws, under my fangs as I tear and rip them apart and open. I eat, I devour and I cry and I scream. What have they done to me?"

iii - Rex tremendae - Wofgang A. Mozart.

Calista as a commandant in War, in the 19th century. The very first battles of in the War Against the Witches, for revenge. Turning the mortal and immortal realms upside and down.

"The Art of War. I watch my armies of vampires and ghouls, the passion, the fever, one that bleeds from my heart to feed their minds, as I stand, in Pride, at the top of the hill, at the birth of an era. It is truly art, a canvas I am written in history. To watch the bodies dance through the blood and the blades. My soul is filled with a rage and hunger I wish for the world of Tomorrow to never cease tasting. I, the traitor of the Night will soon, seize the day.

iv - Gnossienne n° 3 - Erik Satie.

Calista after losing the War, 50 years later in the 20th century. Suicidal Madness has taken her. Hidden, away from whom would want to capture her as the War Criminal she has become.

"Death will not seize me. I have tried to cut my head with a saw more than I could count. I do feel the pain. My own bone breaking in a bath of black blood. It is only pleasure to me as I see closer and closer to my end. My head hits the ground and rolls, rolls, rolls. I can see it, the body, falling onto the ground, I smile and rest my eyes. It is a small death. It grows back however, the head and when I re open my eyes, I can feel my body again, attached as the previous skull remains in a corner. They don't rot, they simply aren't inhabited anymore. I have a hundred of these, my heads, in the castle gardens."

v - Vermillion - Slipknot

Calista as shareholder of the RLC company, in the 21st century. Living among the humans, in search of new powers to fight the Gods, defeat Immortality all together. "The only curse I have known was this eternal life. It ends now. No longer trapped I want to feel. It is not only my own Immortality that I will end but all Immortality. I will take back to the Gods what they have stolen from me. The Choice. The Choice to live, the Choice to die. the choice to never bare such an existence. It shall be under my command now that their gentle little eternal lives end. I only need the power, that one power I have been seeking for centuries now. I can smell it in these modern times, birthing. It shall be mine to collect. Soon."

tagged by : @ofgentleresolve @tewwor @rippleofwords (Thank you my loves)

tagging : @mythvoiced (Sarang my Everything) @serpentainted (Beryl) @solitvrs @fleuresins @amoresins (Mari) @antiromantlc @tvsteoftrvgedy (They have the same eras eep ) @eclavigne @jeoseungsaja (Saja) @antiresolution @yuelianghua

#Calista's lore is a whole rollercoaster#I am extremely proud of this playlist I will be honest#It's Intensity it's Sorrow it's Pain it's Madness it's Grand it's Calista#Realizing I haven't put Lacrimosa I'm just-#Lacrimosa would have been the 6th - Calista drinking bottled blood in 2143 watching the world crumble as she she started the apocalypse#Ferre asked for Quinn and I will do Quinn after Calista#Maybe I will do Ilana too I will see#I don't know who was tagged SO I'm just tagging whoever crosses my mind and whom im sure hasn't done it#셋 𝐂𝐀𝐋𝐈𝐒𝐓𝐀 / headcanons.#셋 𝐂𝐀𝐋𝐈𝐒𝐓𝐀 / the immortal.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book 46: The Borgias and Their Enemies

The all mighty RNG brought 945 History:Europe:Italy. So I chose Christopher Hibbert's The Borgias and Their Enemies: 1431–1519. It essentially covers Rodrigo Borja's ascent to power to Lucretia Borgia's death with some context before and after.

The first chapter describes how Rome was a shithole even for the middle ages before popes returned to it (they had abandoned it for France for a while) and then there were three goddamned popes even, and finally things settled down and popes returned to Rome and they wanted a strong leader over a pious one necessarily, so they elected Rodrigo Borja, made a cardinal at a precipitously young age by his uncle Pope Calixtus III (Not uncommon, about every Pope of that age - even the more "honest" ones- promoted relatives and friends left and right). And let's be frank, Rodriogo- AKA Pope Alexander VI, was not one of the more "honest" ones.

He was the first Pope to admit to his children being his and not "nephews" as the phrase "nepotism" comes from. And I think that reflects his biggest downfall. His son, Cesare was a bastard in every sense of the word. He killed his brother and brother-in-law and a lot of other people and his dad still supported him and used simony increasingly heavily to fund his wars.

The Borgias (Italian for the Spanish Borja) are quite well known for poison so it was very disappointing to find out historically it seems only to be mentioned in Alexander VI's death, rumored as a poisoning attempt gone wrong, but quite possibly just some pedantic disease. Lucrezia Borgia in particular, aside from having an asshole dad and brother seems to be made out as all right if not a little into secular humor for the time. So, big whoop.

SHOULD YOU READ THIS BOOK: Sure, if you want a rundown of Italian history in the 1400s-to early 1500s I'd give it a go. There's a who's who of that period of Italian history including Michelangelo, Leonardo Da Vinci, Titian, the guy who broke Michelangelo's nose (Pietro Torrigiano), Nicholo Machiavelli, etc. The only thing I'd suggest is getting a map of Italy of the time to figure out what the sam hill is so important about Naples, etc.

ART PROJECT:

In a family known for its licentiousness the Feast of the Chestnuts stands out as a particularly bawdy episode in which they gave an orgy in which courtesans groped naked on their hands and knees in cadlelight searching for roasted chestnuts. Sorry for the poor scale in this, as I had an artistic vision in mind and stuck to it.

#the borgias#chestnuts#banquet of the chestnuts#52books#52booksproject#dewey decimal system#rng#christopher hibbert#rodrigo borgia#cesare x lucrezia#pope alexander vi

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

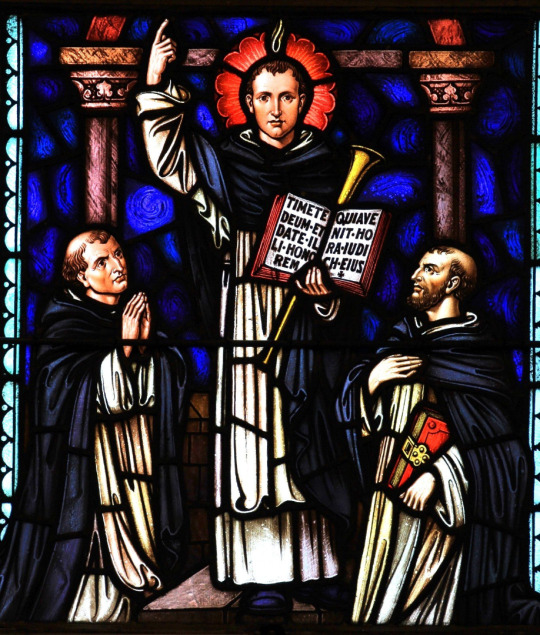

THE DESCRIPTION OF SAINT VINCENT FERRER The Patron of Builders and Construction Workers Feast Day: April 5

"If you truly want to help the soul of your neighbor, you should approach God first with all your heart. Ask him simply to fill you with charity, the greatest of all virtues; with it you can accomplish what you desire."

One of the greatest preachers of the Dominican order and dubbed the 'Angel of the Last Judgment', Vincent Ferrer was born on January 23, 1350 in Valencia.

From his parents (Guillem Ferrer and Constanca Miquel), he learned to love the poor, to fast on Wednesdays and Saturdays, and to have intense devotion to Jesus and Mary. Legends surround Vincent's birth. It was said that his father was told in a dream by a Dominican friar that his son would be famous throughout the world. His mother is said never to have experienced pain when she gave birth to him. He was named after Vincent Martyr, the patron saint of Valencia.

After joining the Order of Preachers (Dominicans) at the age of 18, he soon became a famous preacher, and everywhere, his lectures and sermons met with extraordinary success.

Vincent said to his fellow priests: 'In your sermons, use simple language and precise examples. Each sinner in your congregation should feel moved as though you were preaching to him alone. An abstract discourse hardly inspires those who listen.'

Vincent traveled throughout Europe, preaching mainly on sin, death, hell, eternity and the speedy approach of the day of judgement. He spoke with such energy that most of the listeners confessed their sins and repented from their sinful life. Several priests traveled with him, helping the saint in his ministry.

He instructed them in this fashion: 'When hearing confession, you should always radiate the warmest charity. Whether you are gently encouraging the fainthearted or putting the fear of God into the hardheaded, the penitent should feel that you are motivated only by pure love.'

On April 5, 1419 in Vannes, while delivering his last sermon, Vincent died at the age of 69. He was buried in Vannes Cathedral and was canonized as a saint by Pope Calixtus III in 1455.

#random stuff#catholic#catholic saints#dominicans#order of preachers#vincent ferrer#vicente ferrer#builders#prisoners#construction workers#plumbers#fishermen#spanish orphanages

0 notes

Photo

house borgia + history

#cesare borgia#lucrezia borgia#juan borgia#rodrigo borgia#alexander vi#gioffre borgia#calixtus iii#house borgia#the borgias#borgia#history#theborgias*#blood tw#my gifs#creations*

337 notes

·

View notes

Note

To what extent do you think the prejudice the Borgias faced in Italy as Spaniards and specifically because they were from Valencia shaped their lives and the stories that were later told about them (the Borgia myth)? Everything I've read kind of dismisses or glosses over it.

Hm, yeah, the themes of prejudice regarding the Borgia family do tend to get dimiss or gloss over it, you’re right. Most works I have read only scratches the surface about that (and many other things, too), the one I found covered it the most was José Catalán Deus’s bio about Cesare, so if you speak Spanish, it might be worth a try, even though I still think he was rather shy about it and he failed to make the right connections at times. Without getting too much into this, the main problem I noticed in terms of literature is that, with some exceptions, you have a group of biographers/historians who seem clueless about these prejudices, and who underestimate the impact it had in the Borgias' lives, and how they and their actions were perceived and recorded in history. Many of them don’t see it as being a particularly relevant issue in order to tell their history, not how they want to tell it anyways, it is treated as a side issue rather than a fundamental one, which imo it’s one of the causes that leads to messy, lazy and unsubstantiated claims and conclusions on their part, or the repetition of it. The Borgia family, in their eyes, were just another noble family, when it’s not quite so. Their situation was more complex than that, and unique in some ways, the dynamics they had to deal with, both on a personal and political level, for the most part was different and specific to them. And then you have a group of biographers/historians who are aware of it, to varying degrees, however they seem either unwilling or not interested in delving too much into it, because doing so brings a direct conflict in how one must approach, and use the primary sources, especially when it comes to Rodrigo and Cesare, (there is such a wild arbitrary selection of how these sources are used with them, scholars really pick and choose which pieces of what sources to use depending on what they want to present, and they take so many things at face value, gladly so sometimes, it’s extraordinary to notice), and that in turn would conflict with much of the general, common narratives and character assessments made about the Borgia men, and that's not something most of them want to confront and/or recognize, I think, for various reasons, so they just make a quick mentioning of these prejudice-related issues, mostly the Spaniard one, and they move on with their story. That being said, I’m not sure if there is a connection between the prejudice the Borgias faced in Italy with the fact they were from Valencia specifically, anon. I’ve never came across anything pointing to that in my readings, but if you have something, please let me know because it would be interesting to read about. To my understanding, Italians of the time didn’t seem to make these region distinction with foreigns. It didn’t matter to them if a Spaniard was from Valencia or Barcelona, for example, what they saw was that he/she were a Spaniard and they were all put in the same group, as Spaniards, with the same ideas, right and wrong, being attached to them and their characters, as well as the same loathing Italians usually felt for them. The prejudice faced for being Spaniards is very pronounced in the historical material about the Borgia family, from Calixtus’s papacy to Alexander’s papacy and afterwards. Together with the prejudice faced due to nobility rank, (they weren’t seen as noble enough, or at all, by those who came from more ancient, noble families, and that carried a huge importance in the society they lived in), and the antisemitism linked to the suspicion, which only grew stronger after 1493, of Rodrigo and his children being “marranos”, particularly from places like Venice and Florence. This term “marrano”, which initially might have meant “atheist” from Savonarola and his fanatic followers, over time it started to also or exclusively mean “secret Jew”, and it was used as a way of describing the Borgias, and the Spaniards around them, as an insult, or as a reason not to trust them, and at least on one occasion, there is a historical record showing that even the word Jew was openly used as an insult against Cesare in 1503, he was called a “Jewish dog” by his enemies who wanted to kill him in Rome. So overall, these prejudices, alongside the politics, have shaped the Borgias’ lives and the stories told about them to a large extent, no doubt. On a personal level: for the first Borjas who went to Italy, namely: Alfons de Borja, and his nephews: Rodrigo and Pedro Luís de Borja, they had to adapt to a different culture while getting used to the fact they would always be seen as foreigners, Spaniards foreigners no less, which made things more difficult and it earned them another kind of treatment from others, we can’t know how that made them feel, or how much it might have upset them, but in any case, it was just a fact of their lives in Italy and they had find ways of dealing with it. For the Borgia children: Juan, Cesare, Lucrezia and Gioffre, I don’t think the culture part applies to them, given they most likely were born in Rome, and they were raised in Rome, but the second part does, and maybe for them it was confusing too, because if they were born in Rome, technically speaking they were Italians (or better said Romans), but Italians did not see them like that because of their Spaniard family roots, and because they were proud of it, openly displayed it by speaking the Spanish tongue among themselves, dressing in the Spanish fashion, dancing the Spanish dances, participating in the bull fights, but most of all: of clearly preferring the company of Spaniards who were part of their household, which seems to have bothered many around them, the fact they stood firmly with their own culture and people, see: they weren’t rude, Cesare in particular is noted as always being polite, patient and amiable with them, but he didn’t seem inclined to cater to them and their customs, although I think he incorporated a lot of the Roman customs, as did his siblings, but never above his own, and not in the way they wanted him to, so it rubbed them the wrong way, and it’s a constant complaint you see made about him, his father and his sister. As they grew up and entered the public/political stage, esp. after the election of Rodrigo as pope Alexander because that was the moment their lives really changed and everything became more real and dangerous for them, I think they all became more aware of these issues, and it’s something they also had to get used to it, the different dynamics and the insults made about themselves and their family, not only on the basis of being Spaniards, but as I said above, on the basis of social rank and the strong antisemitism sentiment of their times. I speculate sometimes that it’s possible this made them even more united and loyal to each other as a family, to only trust family members and people inside their circle, it was a matter of safety as well as comfort. Their situation was not one other nobles families shared, actually, maybe with the exception of the Medici family, they had little in common with them I'd say. And in addition to that, I can see how the hostile environment they lived in might have helped them further in building character, in learning how to be resilient. They display such creativity and diplomacy when solving problems, and definitely persistance in achieving their goals. It's one trait I really like about the Borgia family as a whole, but in particular with the trio Rodrigo, Cesare and Lucrezia, it's how they worked around obstacles and adversities, instead of sitting around feeling sorry for themselves, going "Oh, how unfair!" about these prejudices they faced, they worked hard, and they just kept going, patient and persistently. The unfairness, the hatred, the jealousy, the setbacks didn't stopped them, it seems they paid little mind to it (perhaps to a fault), and I think it even encouraged them to succeed, given so many people wanted them to fail and/or die. And on a political, historical level: it heavily influenced the defamation campaigns made about them by their political rivals, these campaigns were primarily motivated by political motives, yes, but they equally echo very clearly a high dose of these prejudices against the Borgia family, it is in their words and narratives used in the pamphlets and rumours that circulated Italy and Europe, the double standards applied to them and their actions, (which are still around today, even within the modern section of Borgian literature depending on which Borgia they are talking about), what Rodrigo, Cesare and Lucrezia did or were said to have done always generated more gossip and hypocritical condemantion than the actions of the other Italian nobles and European monarchs. There is a ridiculous sense of self-righteousness that started when they were living and never stopped. The ways they were used as scapegoats (Cesare most of all) for the social and political problems of the 15th century Italian society, and by Protestants in the 16th century and onward. All of this consolidated the Borgia myths, how they are seen in history, their terrible reputation, our ideas about of their characters, their actions, etc, some of it has been challenged, even if shly so sometimes, but much of it sadly is still presented in modern history as “facts” or as “the truth” about the Borgias, most of all when it is about Rodrigo and Cesare Borgia.

#anon ask#ask answered#house borgia in history#the borgias#calixtus iii#rodrigo borgia#alexander vi#cesare borgia#juan borgia#lucrezia borgia#gioffre borgia#tusertha#i hope this is somewhat coherent and helpful anon#i forgot it was in my drafts and now i'm like: hmmm does this make sense? did i answered the question?#i tried my best but if i didn't let me know!#;)

38 notes

·

View notes

Photo

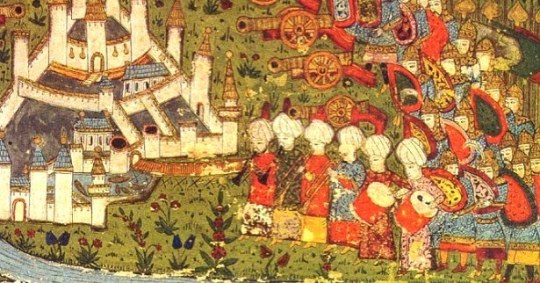

Pope Callisto III reaffirmed the idea of resuming the Crusade of the Church and of Christian principles for the conquest of Constantinople against "the anger of the Turks" from the point where Niccolò V had to suspend it for the coming of death. But he, like his predecessor, despite the preaching and the many ambassadors sent everywhere, had to deal with the shameful indifference of the european rulers against a new venture against infidels. Those rulers were solely committed to defending their interests, and did not consider the Turks threatening their own Western civilization. Charles VII of France long forbade the publication of the Crusade Bull issued in his kingdom on May 15, 1455, as well as forbidding the collecting of the tithes. The same thing happened in other countries. There were those who, like the Duke of Burgundy, collected them but put them in their pockets. In short, no one felt the urgency of a new holy war. Callisto continued to preach and prepare reconciliation with the spirit of a Spanish whose country had for centuries suffer the invasion of Muslims. He was building a fleet of sixteen triremes in Rome, on the Tiber. Ripa Grande became a real shipyard among the amazement of the population. And he, with tears in his eyes for emotion, looked away in the distance from the windows of his palace, the ships coming up from day to day. If Niccolò, his pale predecessor, had been a humanist among humanists, Callisto showed more interest in opposing Ottoman danger than in the diffusion of culture, so much to sell away a large number of precious volumes of the Vatican Library along with many objects of St. Peter's treasure to arm the fleet and drive out the infidels from Europe. Or he deprived those books of their gold-plated ornaments, causing the wrath of the curial letterati. He tore from an ancient, marble sarcophagus, discovered by accident near St. Peter's, all valuable objects, without worrying that the tomb probably contained the remains of Emperor Constantine and one of his sons. He melted the gold and silver found in the grave. From his canteen he banished the silverware saying, "I'm fine with terracotta dishes". The money was never enough, and then the pontiff, with a bull, imposed tithes and promised indulgences to anyone who had somehow helped the anti-Turks enterprise under the exhortation of talented preachers. Source: Antonio Spinosa - La saga dei Borgia

#i borgia#the borgias#pope calixtus iii#papa callisto III#alonso de borja#alfonso borgia#christian zeal#crusade#church#ottoman empire#maometto ii#constantinople#clement v

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Unlike the majority of sixteenth-century women who worked as silk-weavers, butter-makers, or house servants, Vannozza Cattanei (1452 [?]–1518) was exceptional, as she owned a business in Renaissance Rome, a category of work that, according to Alice Clark in Working Life of Women in the Seventeenth Century, was the least open to women. Thus, Cattanei, better known as the lover or mistress of Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia, later Pope Alexander VI (1492–1503), achieved what few women of her time could: she acquired, sold, rented, and administered more than a handful of locande (inns or hotels) in the center of Rome. This essay explores the personal and professional life of Vannozza Cattanei in order to chart her successes as a businesswoman in hotel proprietorship and management, work that allowed her to create a public identity through architecture.

Cattanei was not the typical “invisible” mistress, a term coined by Helen Ettlinger, for her life, her relationships, and her importance as the mother of the Borgia offspring kept her visible throughout history. Historians, art historians, and writers of fiction usually emphasize her roles as the mistress of the powerful Cardinal and as the mother of his children: Juan, Duke of Gandia; the notorious Cesare; Lucrezia, Duchess of Ferrara; and Joffre. Certainly, Cattanei’s life was scandalous by many standards. While married to one man, she lived and slept with, and bore children to another. Her accumulated wealth was not only based on her husbands’ assets, but on her close relationship to Alexander VI. Cattanei’s role as proprietor of successful locande was dependent on three factors coming together in her favor at the right time: money, opportunity, and location.

It was through her marriages and relationship with Alexander VI that Vannozza acquired the needed funds to purchase or rent the buildings that she converted into her hotels. Although little historical evidence remains that illuminates Cattanei’s early life, her adult life, during which she married three times and outlived all of her husbands, is quite well documented. She first wed Domenico da Rignano in 1469, most likely at the age of 27, and widowed for the first time in 1474. Together with Domenico, she purchased a house on the Via del Pellegrino, near Campo dei Fiori, for 500 ducats, of which 310 were from her dowry. Umberto Gnoli believes that this house might have been a gift from Cardinal Borgia as a sort of recompense for Domenico, although he offers no evidence to support this statement.

Cardinal Borgia, while holding the high-ranking office of Vice Cancelliere della Chiesa, an appointment that he received from his uncle, Pope Calixtus III Borgia, built a magnificent palace near the Tiber River, for many years the locus of the relationship between him and Cattanei. However, Cattanei, and eventually the Borgia children, would have claimed their legal domicile to be the house in which she lived with her husband. In 1474, while married to Domenico, Cattanei bore Borgia a son, Juan; a year later, Cesare Borgia was born. Domenico’s death in 1475 left her a widow for the first time. Although no known documents reveal the wealth she possessed at this time, she certainly owned the house on the Pellegrino and she inherited a house whose present-day address is Via di S. Maria in Monticelli. Demolished in the nineteenth century, it once displayed the Rignano family coat of arms.

While a widow, Cattanei gave birth in 1480 to a third Borgia child, a girl named Lucrezia; she then married again. Cattanei’s second husband, Giorgio della Croce, was an educated man from Milan. Why she decided to wed Giorgio is not known, but it might have been a legal agreement so that she could publicly continue her living arrangements with the powerful Cardinal Borgia. Giorgio undoubtedly benefitted from the arrangement; he received a papal appointment in the same year as his wedding. A year later, Cattanei gave birth to a fourth Borgia child, her third son, Joffre. Shortly after Joffre’s birth, Cattanei and the cardinal terminated their cohabitation. By 1486 Cattanei was living with her husband Giorgio; he fathered her next child, Ottaviano, who died after only two months.

At Giorgio’s death that same year, his inventory revealed that he and his wife owned two houses on the Pellegrino and one on the Piazza di Pizzo Merlo because the couple’s only son had died. Widowed again, Cattanei now had legal ownership of all properties. With her relationship as mistress to Cardinal Borgia now over, the widow married again, on June 8, 1486, with a 1000-ducat dowry. Her third husband, the Milanese Carlo Canale, was in the service of Cardinal Giovanni Giacomo Sclafenato of Parma. Both Cardinal Sclafenato and Carlo moved to Rome, where Carlo’s career prospered. Over the next few years, Canale and Cattanei bought vigne and houses in the Rione Monti, not far from the church of San Martino.

Many years later when Cattanei donated considerable sums to charitable organizations, she asked that prayers be said by the priests of San Salvatore for herself and her husbands—save for Domenico whom she excluded. According to Ettlinger, it was often financially advantageous for a man to allow his wife to conduct a carnal relationship with another, usually more powerful man (“Visibilis,” 771). Cattanei and her husbands bought and sold a variety of properties. She also received, as gifts, many items of expensive jewelry. After her relationship with the cardinal had ended and all three husbands had died, she was left a wealthy widow and continued to live in Rome. During her third marriage, she and her husband had started renting and buying locande in the center of Rome, which most probably brought in considerable sums of money.

Cattanei managed at least six of these small hotels, thus making her an accomplished businesswoman. Gnoli wrote that the terms ospizio, locanda, taverna and osteria all meant rented rooms, usually with food service. He estimated a total of sixty establishments in the center of Rome in the second half of the fifteenth century, the period when Cattanei’s business was flourishing. This figure indicates that she controlled about 10% of the hotel business in the central area around Campo dei Fiori, the major outdoor market where most of the small hotels in this period could be found. The circumstances of Cattanei’s career as an owner of small hotels and their locations can be recovered through documentation of sales, rents, and some lawsuits.

She operated at least six hotels, whose exact locations are known, though there remain no records concerning their day-to-day operations. Along the Tiber River was the locanda or osteria named the Biscione, very close to the so-called Tor di Nona, a medieval stronghold of the Orsini; from the early fifteenth century, it was used as a pontifical prison. Not far from the Biscione was the Hosteria della Fontana, the Leone Grande, and the Leone Piccolo. The most famous of her hotels was the Locanda della Vacca, a building still standing on its original corner of the Via dei Cappellari and the Via del Gallo at the edge of the Campo dei Fiori, the site of Rome’s famous market place. On November 10, 1500, Cattanei, under the name Vannozza di Carlo Canale, bought half of the Vacca building from Leonardo Capocci, a priest and canon of St. Peter’s, for 1370 ducats.

Her husband had died by 1500, so she was acting on her own and was in complete control of her own finances during these negotiations. Apparently owning just half of this centrally-located building did not satisfy her, but not until after 1503 was she able to purchase the other half, for the death of Pope Alexander VI and the turmoil that followed likely interfered with the transactions. Documents dated April 1, 1504 refer to her as Vannozza Cataneis de Borgia and verify as false the previous transaction of buying the Vacca and a house on the Via Pellegrino (vendita era stata finta). After the Pope’s death she probably needed to have her claims legalized or at least recognized as valid. She finally acquired the other half of the Vacca building for 1500 ducats from the brothers Pietro, Antonio, and Ciriaco Mattei.

The exact number of rentable rooms in the Locanda della Vacca is uncertain. However, a rough drawing of the ground plan of the building from 1563 exists in the Archivio di Stato, Rome. The three-story building sat at the busy intersection of the Via dei Cappellari and Vicolo del Gallo. The main doorway, on the Cappellari side, functioned as the main entrance. Once inside, corridors led to the many rooms and a courtyard on the ground level, while there were as many as five staircases leading to the rooms on the two superior floors. Along the front of the building were rentable spaces for four shops which at one time were occupied by a wine shop, a meat shop, a shoe shop, and a hair salon, which provided goods and services needed by tourists and visitors.

Cattanei understood the importance of timing and location in real estate. She acquired the first half of the Vacca in 1500—the year when her former lover, now Pope Alexander VI, called a Jubilee Year—so that she profited from renting rooms to the increased number of visitors to Rome. According to a recent article by Ivana Ait, Cattanei’s career as a female proprietor of several small hotels coincides with a surge in the economic life of Rome, largely due to the return of the papacy from Avignon in 1420 that brought a continuous supply of cardinals, ambassadors, and many others to the city. Records indicate that during the Jubilee of 1450 called by Pope Nicholas V, there was a scarcity of food and beds for the many pilgrims to Rome.

… Cattanei’s position as former mistress to the Pope and mother of the Borgia children would have helped ensure a solid standing with the Apostolic Camera during the early years of the sixteenth century. Whereas her beauty and personal charms may have brought her money and opportunity, it was her sharp business acumen, like Agnelucci’s, that helped her establish herself as one of the most successful female proprietors in Rome. Although the number of hotels run by men was certainly greater than those owned by women, Cattanei, Agnelucci, and de’ Calvi bring to light the successful careers of some women, who managed their own businesses in Renaissance Rome. In her later years Cattanei, as a pious widow, bestowed many large charitable gifts on her favorite institutions: she even donated her Locanda della Vacca to the Hospital of S. Salvatore near St. John Lateran.

Her generosity to the Ospedale di S. Salvatore can be documented by quite a large file of original documents clearly dated 1502, which print her name in large letters as Vannozza Borgia de Catanei. In another document, a notary identifies her as Vannozza Cattanei detta anche Borgia, and yet another as Vannozza Borgia dei Cattanei. She was clearly using the Borgia name to fashion her own identity despite the fact that she was never the legal wife of the cardinal. In fact, during her own life Cattanei chose to assume public visibility of her connection to the Borgia family by commissioning Sebastiano Pellegrini da Como to renovate the Locanda della Vacca and display her coat of arms prominently on the façade.

The coat of arms included heraldic symbols of the Cattanei, the Canale, and the Borgia, constructing a public identity that linked her to her father’s line, her husband’s line, and the line of her lover and children. Despite her successes in business and her charitable works, Venetian Senator and historian Marino Sanudo provided the following description of her funeral, dated December 4, 1518: “With the Company of the Gonfalone, [Vannozza Cattanei] was buried in Santa Maria del Popolo. She was buried with pomp almost comparable to a cardinal. [She] was 66 years old and had left all of her goods, which were not negligible, to St John Lateran [location of the Hospital of S. Salvatore]. The funerals of the cubiculari/servants of the Pope’s bedrooms are not solemn occasions to some.”

The report indicates that her generosity to San Salvatore was well known, although her relationship with a cardinal who became pope was equally well known, and overshadowed her accomplishments. I have tried to make the case that Vannozza Cattanei was much more than the whore of a cardinal who later became Pope. She was a wife, a widow, a successful businesswoman, and a pious woman with a long record of charitable activity. Instead of being known solely as the mistress of Alexander VI, or the mother of the Duke of Gandia, she should also be remembered for her business acumen and her piety: for this, she was celebrated in the records of her charitable gifts as La Magnifica Vannozza, a noble and generous benefactress.”

- Cynthia Stollhans, “Vannozza Cattanei: A Hotel Proprietress in Renaissance Rome.” in Early Modern Women

50 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi, I’ve been tasked with researching Richard Plantagenet for a paper and thus far found extremely negative accounts of the king, his religious bigotry being a reoccurring theme (his treatment of Jewish dignitaries attending his coronation and his reasoning to join the third crusade etc)

I stumbled across your wonderful tag for Richard at the weekend and wondered if you wouldn’t mind sharing your informed opinion of Richard and his views on religions ? Your writing seems very well balanced regarding his attributes and flaws. Thanks :)

Oof. Okay. So, a short and simple question, then?

Quick note: when I was first reading your ask and saw "Richard Plantagenet," I briefly assumed that you meant Richard Plantagenet, father of Edward IV, or perhaps Richard III, both from the Wars of the Roses in the fifteenth century, before seeing from context that you meant Richard I. While "Plantagenet" was first used as an informal appellation by Richard I's grandfather, Geoffrey of Anjou, it wasn't until several centuries later that the English royal house started to use it consistently as a surname. So it's not something that Richard I would have been really called or known by, even if historians tend to use it as a convenient labeling conceit. (See: the one thousand popular histories on "The Plantagenets" that have been published recently.)

As for Richard I, he is obviously an extremely complex and controversial figure for many reasons, though one of the first things that you have to understand is that he has been mythologized and reinvented and reinterpreted down the centuries for many reasons, especially his crusade participation and involvement in the Robin Hood legends. When you're researching about Richard, you're often reading reactions/interpretations of that material more than anything specifically rooted in the primary sources. And while I am glad that you asked me about this and want to encourage you to do so, I will gently enquire to start off: when you say "research," what kind of materials are you looking at, exactly? Are these actual published books/papers/academic material, or unsourced stuff on the internet written from various amateur/ideological perspectives and by people who have particular agendas for depicting Richard as the best (or as is more often the case, worst) ever? Because history, to nobody's surprise, is complicated. Richard did good things and he also did quite bad things, and it's difficult to reduce him to one or the other.

Briefly (ha): I'll say just that if a student handed me a paper stating that Richard was a religious bigot because a) there were anti-Jewish riots during his coronation and b) he signed up for the Third Crusade, I would seriously question it. Medieval violence against the Jews was an unfortunately endemic part of crusade preparations, and all we know about Richard's own reaction is that he fined the perpetrators harshly (repeated after a similar March 1190 incident in York) and ordered for them to be punished. Therefore, while there famously was significant anti-Semitic violence at his coronation, Richard himself was not the one who instigated it, and he ordered for the Londoners who did take part in it to be punished for breaking the king's peace.

This, however, also doesn't mean that Richard was a great person or that he was personally religiously tolerant. We don't know that and we often can't know that, whether for him or anyone else. This is the difficulty of inferring private thoughts or beliefs from formal records. This is why historians, at least good historians, mostly refrain from speculating on how a premodern private individual actually thought or felt or identified. We do know that Richard likewise also made a law in 1194 to protect the Jews residing in his domains, known as Capitula Judaeis. This followed in the realpolitik tradition of Pope Calixtus II, who had issued Sicut Judaeis in c. 1120 ordering European Christians not to harass Jews or forcibly convert them. This doesn't mean that either Calixtus or Richard thought Jews were great, but they did choose a different and more pragmatic/economic way of dealing with them than their peers. This does not prove "religious bigotry" and would need a lot more attention as an analytical concept.

As for saying that the crusades were motivated sheerly by medieval religious bigotry, I'm gonna have to say, hmm, no. Speaking as someone with a PhD in medieval history who specialised in crusade studies, there is an enormous literature around the question of why the crusades happened and why they continue to hold such troubling attraction as a pattern of behavior for the modern world. Yes, Richard went on crusade (as did the entire Western Latin world, pretty much, since 1187 and the fall of Jerusalem was the twelfth century's 9/11). But there also exists material around him that doesn't exist around any other crusade leader, including his extensive diplomatic relations with the Muslims, their personal admiration for him, his friendship with Saladin and Saladin's brother Saif al-Din, the fact that Arabic and Islamic sources can be more complimentary about Richard than the Christian records of his supposed allies, and so forth. I think Frederick II of Sicily, also famous for his friendly relationships with Muslims, is the only other crusade leader who has this kind of material. So however he did act on crusade, and for whatever reasons he went, Richard likewise chose the pragmatic path in his interactions with Muslims, or at least the Muslim military elite, than just considering them all as religious barbarians unworthy of his time or attention.

The question of how the crusades functioned as a pattern of expected behavior for the European Christian male aristocrat, sometimes entirely divorced from any notion of his private religious beliefs, is much longer and technical than we can possibly get into. (As again, I am roughly summarising a vast and contentious field of academic work for you here, so... yes.) Saying that the crusades happened only because medieval people were all religious zealots is a wild oversimplification of the type that my colleague @oldshrewsburyian and I have to deal with in our classrooms, and likewise obscures the dangerous ways in which the modern world is, in some ways, more devoted to replicating this pattern than ever. It puts it beyond the remit of analysis and into the foggy "Dark Ages hurr durr bad" stereotype that drives me batty.

Weighted against this is the fact that Richard obviously killed many Muslims while on crusade, and that this was motivated by religious and ideological convictions that were fairly standard for his day but less admirable in ours. The question of how that violence has been glorified by the alt-right people who think there was nothing wrong with it at all and he should have done more must also be taken into account. Richard's rise to prominence as a quintessentially English chivalrous hero in the nineteenth century, right when Britain was building its empire and needed to present the crusades as humane and civilizing missions abroad rather than violent and generally failed attempts at forced conversion and conquest, also problematized this. As noted, Richard was many things, but... not that, and when the crusades fell out of fashion again in the twentieth century, he was accordingly drastically villainized. Neither the superhero or the supervillain images of him are accurate, even if they're cheap and easy.

The English nationalists have a complicated relationship with Richard: he represents the ideal they aspire to, aesthetically speaking, and the kind of anti-immigrant sentiment they like to put in his mouth, which is far more than the historical Richard actually displayed toward his Muslim counterparts. (At least, again, so far as we can know anything about his private beliefs, but this is what we can infer from his actions in regard to Saladin, who he deeply respected, and Saladin's brother.) But he was also thoroughly a French knight raised and trained in the twelfth-century martial tradition, his concern for England was only as a minor part of the sprawling 'Angevin empire' he inherited from his father Henry II (which is heresy for the Brexit types who think England should always be the center of the world), and his likely inability to speak English became painted as a huge character flaw. (Notwithstanding that after the Norman Conquest in 1066, England did not have a king who spoke English natively until Henry IV in 1399, but somehow all those others don't get blamed as much as Richard.)

Anyway. I feel as if it's best to stop here. Hopefully this points you toward the complexity of the subject and gives you some guidelines in doing your own research from here. :)

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today the Church remembers St. Bernard of Clairvaux, Monk.

Ora pro nobis.

St. Bernard de Clairvaux, (born 1090 AD, probably Fontaine-les-Dijon, near Dijon, Burgundy [France]—died August 20, 1153 AD, Clairvaux, Champagne; canonized January 18, 1174; feast day August 20), was a Cistercian monk and mystic, the founder and abbot of the abbey of Clairvaux, and one of the most influential churchmen of his time.

Born of Burgundian landowning aristocracy, Bernard grew up in a family of five brothers and one sister. The familial atmosphere engendered in him a deep respect for mercy, justice, and loyal affection for others. Faith and morals were taken seriously, but without priggishness. Both his parents were exceptional models of virtue. It is said that his mother, Aleth, exerted a virtuous influence upon Bernard only second to what Monica had done for Augustine of Hippo in the 5th century. Her death, in 1107, so affected Bernard that he claimed that this is when his “long path to complete conversion” began.

He turned away from his literary education, begun at the school at Châtillon-sur-Seine, and from ecclesiastical advancement, toward a life of renunciation and solitude. Bernard sought the counsel of the abbot of C��teaux, Stephen Harding, and decided to enter this struggling, small, new community that had been established by Robert of Molesmes in 1098 as an effort to restore Benedictinism to a more primitive and austere pattern of life. Bernard took his time in terminating his domestic affairs and in persuading his brothers and some 25 companions to join him. He entered the Cîteaux community in 1112, and from then until 1115 he cultivated his spiritual and theological studies.

Bernard’s struggles with the flesh during this period may account for his early and rather consistent penchant for physical austerities. He was plagued most of his life by impaired health, which took the form of anemia, migraine, gastritis, hypertension, and an atrophied sense of taste.

Founder And Abbot Of Clairvaux

In 1115 Stephen Harding appointed him to lead a small group of monks to establish a monastery at Clairvaux, on the borders of Burgundy and Champagne. Four brothers, an uncle, two cousins, an architect, and two seasoned monks under the leadership of Bernard endured extreme deprivations for well over a decade before Clairvaux was self-sufficient. Meanwhile, as Bernard’s health worsened, his spirituality deepened. Under pressure from his ecclesiastical superiors and his friends, notably the bishop and scholar William of Champeaux, he retired to a hut near the monastery and to the discipline of a quack physician. It was here that his first writings evolved. They are characterized by repetition of references to the Church Fathers and by the use of analogues, etymologies, alliterations, and biblical symbols, and they are imbued with resonance and poetic genius. It was here, also, that he produced a small but complete treatise on Mariology (study of doctrines and dogmas concerning the Virgin Mary), “Praises of the Virgin Mother.” Bernard was to become a major champion of a moderate cult of the Virgin, though he did not support the notion of Mary’s immaculate conception.

By 1119 the Cistercians had a charter approved by Pope Calixtus II for nine abbeys under the primacy of the abbot of Cîteaux. Bernard struggled and learned to live with the inevitable tension created by his desire to serve others in charity through obedience and his desire to cultivate his inner life by remaining in his monastic enclosure. His more than 300 letters and sermons manifest his quest to combine a mystical life of absorption in God with his friendship for those in misery and his concern for the faithful execution of responsibilities as a guardian of the life of the church.

It was a time when Bernard was experiencing what he apprehended as the divine in a mystical and intuitive manner. He could claim a form of higher knowledge that is the complement and fruition of faith and that reaches completion in prayer and contemplation. He could also commune with nature and say:

Believe me, for I know, you will find something far greater in the woods than in books. Stones and trees will teach you that which you cannot learn from the masters.

After writing a eulogy for the new military order of the Knights Templar he would write about the fundamentals of the Christian’s spiritual life, namely, the contemplation and imitation of Christ, which he expressed in his sermons “The Steps of Humility” and “The Love of God.”

Pillar Of The Church

The mature and most active phase of Bernard’s career occurred between 1130 and 1145. In these years both Clairvaux and Rome, the centre of gravity of medieval Christendom, focussed upon Bernard. Mediator and counsellor for several civil and ecclesiastical councils and for theological debates during seven years of papal disunity, he nevertheless found time to produce an extensive number of sermons on the Song of Solomon. As the confidant of five popes, he considered it his role to assist in healing the church of wounds inflicted by the antipopes (those elected pope contrary to prevailing clerical procedures), to oppose the rationalistic influence of the greatest and most popular dialectician of the age, Peter Abelard, and to cultivate the friendship of the greatest churchmen of the time. He could also rebuke a pope, as he did in his letter to Innocent II:

There is but one opinion among all the faithful shepherds among us, namely, that justice is vanishing in the Church, that the power of the keys is gone, that episcopal authority is altogether turning rotten while not a bishop is able to avenge the wrongs done to God, nor is allowed to punish any misdeeds whatever, not even in his own diocese (parochia). And the cause of this they put down to you and the Roman Court.

Bernard’s confrontations with Abelard ended in inevitable opposition because of their significant differences of temperament and attitudes. In contrast with the tradition of “silent opposition” by those of the school of monastic spirituality, Bernard vigorously denounced dialectical Scholasticism as degrading God’s mysteries, as one technique among others, though tending to exalt itself above the alleged limits of faith. One seeks God by learning to live in a school of charity and not through “scandalous curiosity,” he held. “We search in a worthier manner, we discover with greater facility through prayer than through disputation.” Possession of love is the first condition of the knowledge of God. However, Bernard finally claimed a victory over Abelard, not because of skill or cogency in argument but because of his homiletical denunciation and his favoured position with the bishops and the papacy.

Pope Eugenius III and King Louis VII of France induced Bernard to promote the cause of a Second Crusade (1147–49) to quell the prospect of a great Muslim surge engulfing both Latin and Greek Orthodox Christians. The Crusade ended in failure because of Bernard’s inability to account for the quarrelsome nature of politics, peoples, dynasties, and adventurers. He was an idealist with the ascetic ideals of Cîteaux grafted upon those of his father’s knightly tradition and his mother’s piety, who read into the hearts of the Crusaders—many of whom were bloodthirsty fanatics—his own integrity of motive.

In his remaining years he participated in the condemnation of Gilbert de La Porrée—a scholarly dialectician and bishop of Poitiers who held that Christ’s divine nature was only a human concept. He exhorted Pope Eugenius to stress his role as spiritual leader of the church over his role as leader of a great temporal power, and he was a major figure in church councils. His greatest literary endeavour, “Sermons on the Canticle of Canticles,” was written during this active time. It revealed his teaching, often described as “sweet as honey,” as in his later title doctor mellifluus. It was a love song supreme: “The Father is never fully known if He is not loved perfectly.” Add to this one of Bernard’s favourite prayers, “Whence arises the love of God? From God. And what is the measure of this love? To love without measure,” and one has a key to his doctrine.

St. Bernard was declared a doctor of the church in 1830 and was extolled in 1953 as doctor mellifluus in an encyclical of Pius XII.

O God, by whose grace your servant Bernard, kindled with the flame of your love, became a burning and a shining light in your Church: Grant that we also may be aflame with the spirit of love and discipline, and walk before you as children of light; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you, in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever. Amen.

#christianity#jesus#saints#monasticism#god#father troy beecham#troy beecham episcopal#father troy beecham episcopal

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Is The Angelus?

Designed to commemorate the mystery of the Incarnation and pay homage to Mary’s role in salvation history, it has long been part of Catholic life. Around the world, three times every day, the faithful stop whatever they are doing and with the words “The Angel of the Lord declared unto Mary” begin this simple yet beautiful prayer. But why do we say the Angelus at all, much less three times a day?

Most Church historians agree that the Angelus can be traced back to 11th-century Italy, where Franciscan monks said three Hail Marys during night prayers, at the last bell of the day. Over time, pastors encouraged their Catholic flocks to end each day in a similar fashion by saying three Hail Marys. In the villages, as in the monasteries, a bell was rung at the close of the day reminding the laity of this special prayer time. The evening devotional practice soon spread to other parts of Christendom, including England.

Toward the end of the 11th century, the Normans invaded and occupied England. In order to ensure control of the populace, the Normans rang a curfew bell at the end of each day reminding the locals to extinguish all fires, get off the streets and retire to their homes. While not intended to encourage prayer, this bell became associated nevertheless with evening prayer time, which included saying the Hail Mary. Once the curfew requirement ended, a bell continued to be rung at the close of each day and the term curfew bell was widely popular, although in some areas it was known as the “Ave” or the “Gabriel” bell.

Around 1323, the Bishop of Winchester, England, and future Archbishop of Canterbury, Bishop John de Stratford, encouraged those of his diocese to pray the Hail Mary in the evening, writing, “We exhort you every day, when you hear three short interrupted peals of the bell, at the beginning of the curfew (or, in places where you do not hear it, at vesper time or nightfall) you say with all possible devotion, kneeling wherever you may be, the Angelic Salutation three times at each peal, so as to say it nine times in all” (Publication of the Catholic Truth Society, 1895).

Meanwhile, around 1318 in Italy, Catholics began saying the Hail Mary upon rising in the morning. Likely this habit again came from the monks, who included the Hail Mary in the prayers they said before their workday began. The morning devotion spread, and evidence is found in England that in 1399 Archbishop Thomas Arundel ordered church bells be rung at sunrise throughout the country, and he asked the laity to recite five Our Fathers and seven Hail Marys every morning.

The noontime Angelus devotion seems to have derived from the long-standing practice of praying and meditating on Our Lord’s passion at midday each Friday. In 1456, Pope Calixtus III directed the ringing of church bells every day at noon and that Catholics pray three Hail Marys. The pope solicited the faithful to use the noonday prayers to pray for peace in the face of the 15th-century invasion of Europe by the Turks. The bell rung at noontime became known as the “Peace” bell or “Turkish” bell. In 1481, Pope Sixtus IV was petitioned by Queen Elizabeth of England, wife of King Henry VII, to grant indulgences for those who said at least one Hail Mary at 6 a.m., noon and 6 p.m. There is evidence that a bell was rung at those times.

The Angelus Today

By the end of the 16th century, the Angelus had become the prayer that we know today: three Hail Marys, with short verses in between (called versicles), ending with a prayer. It was first published in modern form in a catechism around 1560 in Venice. This devotion reminds us of the Angel Gabriel’s annunciation to Mary, Mary’s fiat, the Incarnation and Our Lord’s passion and resurrection. It is repeated as a holy invitation, calling us to prayer and meditation. For centuries the Angelus was always said while kneeling, but Pope Benedict XIV (r. 1740-1758) directed that the Angelus should be recited while standing on Saturday evening and all day on Sunday. He also directed that the Regina Coeli (Queen of Heaven) be said instead of the Angelus during the Easter season. Over the years many of the faithful have focused the morning Angelus on the Resurrection, the noon Angelus on the Passion and the evening Angelus on the Incarnation.

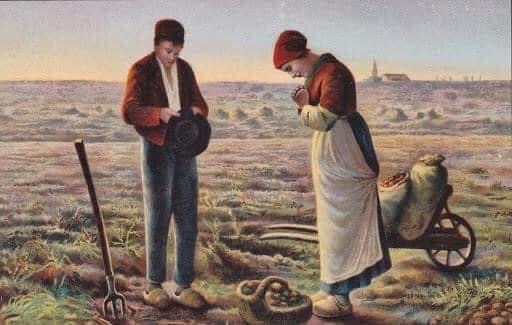

It is said that over the centuries workers in the fields halted their labors and prayed when they heard the Angelus bell. This pious practice is depicted by Jean-François Millet’s famous 1857 painting that shows two workers in a potato field stopping to say the Angelus. There are also stories that animals would automatically stop plowing and stand quietly at the bell.

Like a heavenly messenger, the Angelus calls us to interrupt his daily, earthly routines and turn to thoughts of God, of the Blessed Mother, and of eternity. As Pope Benedict XVI taught last year on the feast of the Annunciation: “The Angel’s proclamation was addressed to her; she accepted it, and when she responded from the depths of her heart … at that moment the eternal Word began to exist as a human being in time. From generation to generation the wonder evoked by this ineffable mystery never ceases.”

1 note

·

View note

Photo

October 14th 1285 saw the second marriage of King Alexander III to Yolanda de Dreux.

We hear a lot about Alexander in my posts due to the events after his death, I will try and concentrate more on his Queen, although she was Scotland’s Queen Consort for only 4 months and 14 days.

In that short time, Yolanda carried the hope of a nation – and its king – to secure the Scottish succession.

Yolande was born into a minor branch of the French royal family, probably sometime in the mid-1260s. Her father was Robert IV, Count of Dreux, who died in 1282 and her mother was Beatrice de Montfort, who died in 1311. She had 2 brothers and 3 sisters. Little is known of Yolande’s childhood but we can imagine that as a junior member of the Capetian dynasty, she grew up amidst some privilege and splendour.

Queen Margaret died in 1275 and within 8 years all 3 of her children were dead; 8-year-old David died at Stirling Castle at the end of June 1281, Margaret died in childbirth on 9th April 1283 and Alexander died at Lindores Abbey in January 1284, sometime around his 20th birthday. Alexander’s heir was now his infant granddaughter by Margaret and Erik, little Margaret, the Maid of Norway, born shortly before her mother’s death.

Whilst Yolande was growing into adulthood Scotland was experiencing a “golden age”, a period of relative peace and prosperity. Her king, Alexander III was married to Margaret, daughter of Henry III of England and the couple had 3 children survive childhood. Their daughter, Margaret, born at Windsor on 28th February, 1261, was married to Erik II, king of Norway, in August 1281. Their eldest son, Alexander, was born on 21st January 1264, at Jedburgh. On 15th November 1282 Alexander married Margaret, the daughter of Guy de Dampierre, Count of Flanders. A younger son, David was born on 20th March 1273. With his entire dynasty resting on the life of his toddler granddaughter, Alexander started the search for a new wife. In February 1285 he sent a Scottish embassy to France for this sole purpose. Their successful search saw Yolande arrive in Scotland that same summer, accompanied by her brother John. Alexander and Yolande were married at Jedburgh Abbey, Roxburghshire, on 14th October 1285, the feast of St Calixtus, in front of a large congregation made up of Scottish and French nobles. Yolande was probably no more than 22 years of age, while Alexander was in his 44th year.

The marriage was the shortest of any English or Scottish king, lasting less than 5 months. Tragedy struck in March of 1286 when Alexander took a tumble down that cliff near Kinghorn.

There followed months of uncertainty in Scotland. She had lost one of her most successful kings and the succession was in turmoil. Little Margaret, the Maid of Norway, had been recognised by the council as Alexander’s heir, but his queen was pregnant; and if she gave birth to a boy he would be king from his first breath. A regency council was established to rule until the queen gave birth. In the event, Yolande either suffered a miscarriage, or the child was stillborn. Some sources, the Lanercost Chronicle in particular, have questioned whether Yolande was pregnant at all, suggesting that she was intending to pass off another woman’s baby as her own. The plan thwarted, the chronicle recorded that ‘women’s cunning always turns toward a wretched outcome‘.¹ However, there are major discrepancies in the chronicle’s apparently malicious account and tradition has the baby buried at Cambuskenneth.

In May 1294 Yolande had married for a second time; Arthur of Brittany was a similar age to Yolande and was the son and heir of Jean II, duke of Brittany and earl of Richmond. Yolande was the second wife of Arthur, who already had 3 sons, Jean, Guy and Peter, by his first wife, Marie, Vicomtesse de Limoges.Yolande and Arthur had 6 children together.

Her second husband died in 1345 and after being widowed for a second time Yolande did not remarry.

During her time in Brittany Yolande continued to administer her Scottish estates; in October 1323 safe-conduct to Scotland was granted to a French knight ‘for the dower of the Duchess of Brittany while she was Queen of Scotland‘.

It seems uncertain when Yolande died. Sources vary between 1324 and 1330, although she was still alive on 1st February 1324 when she made provision for the support of her daughter, Marie, who had become a nun.

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

John Hunyadi’s great victory at Belgrade in 1456 breathed new life into the anti-Ottoman struggle. It effectively halted the Islamic advance into Europe for the next seventy years. News of the Ottoman defeat was hailed throughout the capitals of Europe. Pope Calixtus III, the first Borgia pope, praised the Hungarian leader, declaring Hunyadi an “Athlete of Christ,” comparing him to the great commanders of antiquity. #Hunyadi #Belgrade John Hunyadi and the Defense of Belgrade, 1456 draculachronicle.com/2018/08/20/joh… via @draculachron #Hunyadi #Belgrade #Hungary #1456 https://www.instagram.com/p/BnNyfcOAe5j/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=81rbx10ptsjs

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Blessed Memorial of St Vincent Ferrer O.P. (1530-1419 aged 69) Religious Priest, Miracle-worker, Logician, Preacher, Missionary, Confessor, Teacher, Philosopher, Theologian known as the “Angel of the Apocalypse” and the “Mouthpiece of God” – Patron of brick makers, builders, Calamonaci, Italy, Casteltermini, Agrigento, Italy, construction workers, Leganes, Philippines, Orihuela-Alicante, Spain, diocese of, pavement workers, plumbers, . tile makers. Representation: Bible, cardinal’s hat, Dominican preacher with a flame on his hand, Dominican preacher with a flame on his head, Dominican holding an open book while preaching, Dominican with a cardinal’s hat, Dominican with a crucifix, Dominican with a trumpet nearby, often coming down from heaven, referring to his vision, Dominican with wings, referring to his vision as being an ‘angel of the apocalypse’, pulpit, representing his life as a preacher, flame, referring to his gifts from the Holy Spirit.

Vincent was the fourth child of the nobleman Guillem Ferrer, a notary who came from Palamós and wife, Constança Miquel, apparently from Valencia itself or Girona. Legends surround his birth. It was said that his father was told in a dream by a Dominican friar that his son would be famous throughout the world. His mother is said never to have experienced pain when she gave birth to him. He was named after St. Vincent Martyr, the patron saint of Valencia. He would fast on Wednesdays and Fridays and he loved the Passion of Christ very much. He would help the poor and distribute alms to them. He began his classical studies at the age of eight, his study of theology and philosophy at fourteen.

Four years later, at the age of nineteen, Ferrer entered the Order of Preachers, commonly called the Dominican Order, in England also known as Blackfriars. As soon as he had entered the novitiate of the Order, though, he experienced temptations urging him to leave. Even his parents pleaded with him to do so and become a secular priest. He prayed and practiced penance to overcome these trials. Thus he succeeded in completing the year of probation and advancing to his profession.

For a period of three years, he read solely Sacred Scripture and eventually committed it to memory. He published a treatise on Dialectic Suppositions after his solemn profession, and in 1379 was ordained a Catholic priest at Barcelona. He eventually became a Master of Sacred Theology and was commissioned by the Order to deliver lectures on philosophy. He was then sent to Barcelona and eventually to the University of Lleida, where he earned his doctorate in theology.

Vincent Ferrer is described as a man of medium height, with a lofty forehead and very distinct features. His hair was fair in colour and tonsured. His eyes were very dark and expressive; his manner gentle. Pale was his ordinary colour. His voice was strong and powerful, at times gentle, resonant and vibrant.

Three men claimed to be pope in the 1300s and 1400s. Kings, princes, priests, and laypeople fought one another to support the different claimants for the Chair of Peter. This chaos led to the Western Schism, and God raised up Vincent Ferrer.

When Vincent joined the Dominicans, he zealously practiced penance, study and prayer. He was a teacher of philosophy and a naturally gifted preacher called the “mouthpiece of God.” His saintly life was what made his preaching so effective. Vincent’s subjects were judgment, heaven, hell and the need for repentance.

Even the holiest people can be misled. Pope Urban VI was the real pope and lived in Rome but Vincent and many others thought that Clement VII and his successor Benedict XIII, who lived in Avignon, France, were the true popes. Vincent convinced kings, princes, clergy and almost all of Spain to give loyalty to them. After Clement VII died, Vincent tried to get both Benedict and the pope in Rome to abdicate so that a new election could be held. It hurt Vincent when Benedict refused.

Vincent came to see the error in Benedict’s claim to the papacy. Discouraged and ill, Vincent begged Christ to show him the truth. In a vision, he saw Jesus with Saint Dominic and Saint Francis, commanding him to “go through the world preaching Christ.” For the next 20 years, Vincent spread the Good News throughout Europe. He fasted, preached, worked miracles and drew many people to become faithful Christians. Vincent returned to Benedict in Avignon and asked him to resign. Benedict refused. One day while Benedict was presiding over an enormous assembly, Vincent, though close to death, mounted the pulpit and denounced him as the false pope. He encouraged everyone to be faithful to the one, true Catholic Church in Rome. Benedict fled, knowing his supporters had deserted him. Later, the Council of Constance met to end the Western Schism.

St Vincent always slept on the floor, he had the gift of tongues (he spoke only Spanish but all listeners understood him, he lived in an endless fast, celebrated Mass daily and known as a miracle worker; he is reported to have brought a murdered man back to life to prove the power of Christianity to the onlookers and he would heal people throughout a hospital just by praying in front of it. He worked so hard to build up the Church that he became the patron of people in building trades.

Because of the Spanish’s harsh methods of converting Jews at the time, the means which Vincent had at his disposal were either baptism or spoliation. He won them over by his preaching, estimated at 25,000. Vincent also attended the Disputation of Tortosa (1413–14), called by Avignon Pope Benedict XIII in an effort to convert Jews to Catholicism after a debate among scholars of both faiths.

Vincent died on 5 April 1419 at Vannes in Brittany, at the age of sixty-nine and was buried in Vannes Cathedral. He was canonised by Pope Calixtus III on 3 June 1455. His feast day is celebrated on 5 April. The Fraternity of Saint Vincent Ferrer, a pontifical religious institute founded in 1979, is named for him.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jézus megdicsőülését ünnepli az Egyház

Miután az apostolok Jézusra Messiásként, Isten fiaként tekintettek, ismertette velük mindazt, ami Krisztusra vár

Krisztus mennyei fényben való megjelenése az írások szerint a Tábor-hegyen történt. Itt az arab hódítás előtt három bazilika is épült. Jézus isteni mivoltára Jakab, János és Péter jelenlétében mutatott rá. A színeváltozás (görögül: metamorphószisz; latinul: transfiguratio) a keresztény teológiába értelmezése alapján Krisztus „isteni dicsősége megmutatkozásának az Újszövetség által feljegyzett eseménye”.

Miután az apostolok Jézusra Messiásként, Isten fiaként tekintettek, ismertette velük mindazt, ami Krisztusra vár: el kell mennie Jeruzsálembe, szenvedések hada vár rá, megölik, majd harmadnapon feltámad. A tanítványok ezt nem akarták elfogadni, majd a fegyelmezésük után Jakab, János és Péter kíséretében a hegyre mentek, ahol Jézus arca a naphoz hasonlóan tündökölt, s a fényhez hasonlóan pompázott a ruhája. Ekkor Mózes és Illés is ott „termettek”, akik Jézussal társalogtak. Majd Péter hangot adott annak, hogy jól érzi ott magát, s mondta, hogy ha Jézus is szeretné, hármójuknak készít ott sátrat. S egy fényes felhő megjelenése után hangot hallottak, miszerint „Ez az én szeretett Fiam, akiben gyönyörködöm, reá hallgassatok!”. A tanítványok félni kezdtek, de Jézus bátorító szava erőt adott nekik, s a Tábor-hegyről lefelé jövet utasította őket, hogy a történtekről mindössze a feltámadás után beszélhetnek.

A jeles nap három elnevezést is kapott: Úr színe változatja (Érdy-kódex), Úrnak megváltozása (a Müncheni-kódex naptára) és Jézus táborhegyi színváltozásának ünnepe.

A keleti egyházban Urunk színeváltozása karácsonyt, húsvétot és pünkösdöt követően ez az legszentebb. A nyugati egyház a legelső ezredfordulót, s Jézus akkorra várt visszajövetelével összekapcsolva kezdte nyilvántartani a jeles napot. Ünnepnappá III. Calixtus pápa nyilvánította a nándorfehérvári diadal hálaemlékére, ugyanis az akkori Magyarország végvárának Hunyadi János és Kapisztrán Szent János török ostrom alóli felszabadításának hírét ezen a napon – 1456. augusztus 6-án – kapta. Erről szinte naponta megemlékezünk, méghozzá a déli harangszó hallatán.

Laky Erzsébet

Források: ITT, ITT és Éneklő Egyház – római katolikus népénektár

Képek forrásai: wikipedia és bdsz.hu

#déli harangszó#egyház#Főoldal#Hunyadi János#III. Calixtus pápa#Jézus színeváltozása#Kapisztrán Szent János#nándorfehérvári diadal#Tábor-hegy

0 notes

Photo

house borgia + notable members

#cesare borgia#lucrezia borgia#juan borgia#gioffre borgia#alexander vi#pedro luis borgia#rodrigo borgia#calixtus iii#house borgia#history#theborgias*#my gifs#creations*

308 notes

·

View notes