How does one archive the immaterial, the absent, the inaccessible at times of crisis? How does one make visible disappeared and displaced populations?

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

For Edition IX – Bodies and Technologies the researcher Samia Henni was invited by programme curator Megan Hoetger to develop a new project related to her ongoing research into the French nuclear detonation programmes in the Algerian Sahara. What has emerged is Performing Colonial Toxicity, an expansive research project unfolding across a multimedia immersive installation (7 October 2023 – 14 January 2024; co-produced with Framer Framed, Amsterdam), an experimental repository publication (forthcoming November 2023; co-published with Framer Framed and Edition Fink, Zurich), and – what visitors find here in ificantdance.studio – an online Testimony Translation Project, which begins the long process of digitalizing and translating over seven hundred pages of written and oral testimonies from French and Algerian victims of the nuclear blasts. From each of these platforms Henni experiments with performative modes of exposing and spatializing the inaccessible classified archives of this violent history.

1 note

·

View note

Text

vimeo

Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme, Until we became fire and fire us. Sharjah Walkthrough, 2023.

32 minute 7 channel video, 6 channel sound piece Sublimation prints on fabric dimensions variable, Digital prints on metal dimensions variable, 7 Steel panels dimensions variable This work is composed of several works that come together to create a whole. The project can either be shown in its entirety or specific works from it can be shown as stand alone pieces. Low cloud hum 50x150 cm and 50x100 cm sublimation prints on fabric Two channel sound piece with subwoofer To dig a tunnel in the earth 50x150cm sublimation prints on fabric, Digital prints on metal dimensions variable, corten steel panel Subwoofer Low cloud hang Video 32 min, Digital prints on metal dimensions variable, corten steel panel Until we became fire and fire us 32 minute 2-4 channel video projection, 2-4 channel sound + subwoofer, concrete and metal panels size variable *** The song is the call and the land is calling The land is calling the vanished through the song The land haunts us And we haunt them The shadow, the echo, the ghosts of what remain The loss of our land haunts us. Having been severed from the land we are haunted by it. A forbidden land like a forbidden love. Until we became fire and fire us explore various forms of hauntings, love stories bound to loss, land and self, forms of imprisonment and the call to get free, with sound and song being at the heart of this exploration. In it all is a search for a reconnection to a severed broken land, community, history, one that haunts, imprisons and moves us all at once. The project is a mixed media installation with multiple channel sound and video. It formally explores the idea of hauntings in its aural and visual content and the way in which this material appears and disappears into a given space. Sometimes appearing as poetry from a dissonant voice, a broken melody or intense flashes of text and video, or an imprint from a forbidden land, a forbidden love. This work is part of the wider May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth project

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Paris Review - Six Photos from W. G. Sebald’s Albums

16 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Three Families & Three Families

Three Jerusalem Manuscript Libraries join efforts to preserve vulnerable Islamic and Arab cultural heritage in the city. Produced by Nun Films in collaboration wth the Khalidi Library and ALIPH.

Three Families & Three Families

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Some good news courtesy of the Arab Image Foundation and (the very much missed Dawawine):

2022 marks the 11th – and final – year of the AIF in its current location in Gemmayzeh. After viewing more than a dozen potential spaces across Beirut, we’re delighted to share the news that the ground floor of the Aresco building in Kantari will be the foundation’s new home as of the spring of 2023.

Spread out across two floors and a mezzanine, our new 800 m2 space will accommodate improved preservation and digitisation labs; a larger cool storage room (CSR) and a quarantine area for incoming collections; a work and display area; and a new space dedicated to library resources and to welcoming researchers.

AIF will collaborate with Dawawine, offering a specialised public library that houses both Dawawine’s and the foundation’s extensive book collections and audiovisual resources, which focus on photography, cinema, theater, and the performing arts. This new joint library and research center will be an important resource for artists, researchers, and scholars alike.

Please see Dawawine’s statement below about our new joint library.

Being alone and in the dark doesn’t agree with us. In this mad city, we found an ally in the Arab Image Foundation, and instead of reinstating a bookstore, we will be experiencing the permanence of a public library. We'll be taking our books out of their boxes soon, and look forward to meeting readers, writers, art-makers, image seekers, and researchers at AIF’s new premises, where Dawawine’s books will find a home. We also hope to resume our programme of film screenings throughout the year 2023. There is so much more we’d like to say, but let us be patient; we'll share more updates with you very soon.

It is our hope that this move will allow us to open our doors wide, welcoming different publics, conceiving diverse programmes, and becoming an open space where people can meet, exchange knowledge, engage with each other, and learn together.

Arab Image Foundation, Issue #2023.01

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“This edition of the Biennale is said to be centered on decolonial engagement, to offer ‘repair . . . as a form of agency’ and ‘a starting point . . . for critical conversation, in order to find ways together to care for the now.’ Yet the Biennale made the decision to commodify photos of unlawfully imprisoned and brutalized Iraqi bodies under occupation, displaying them without the consent of the victims and without any input from the Biennale’s participating Iraqi artists, whose work was adjacently installed without their knowledge. Who is given agency in this form of ‘repair’?”

Rijin Sahakian, “Regarding torture at the Berlin Biennale“ (Artforum)

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

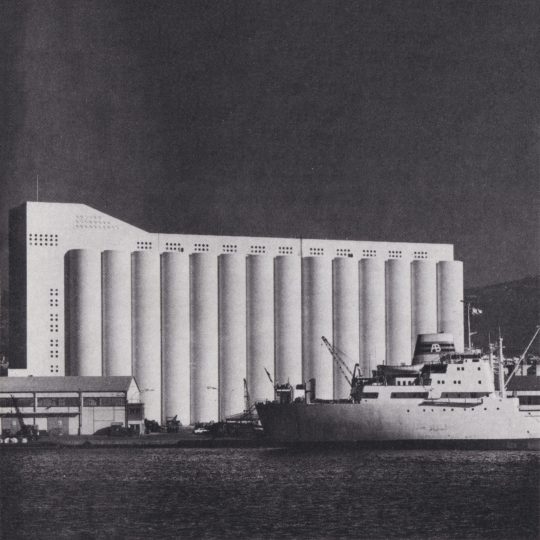

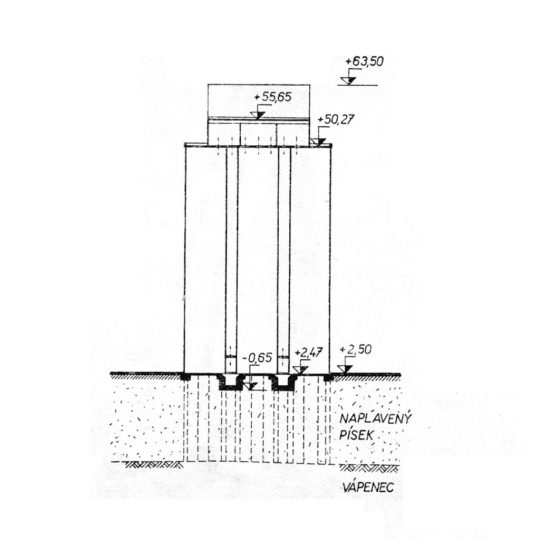

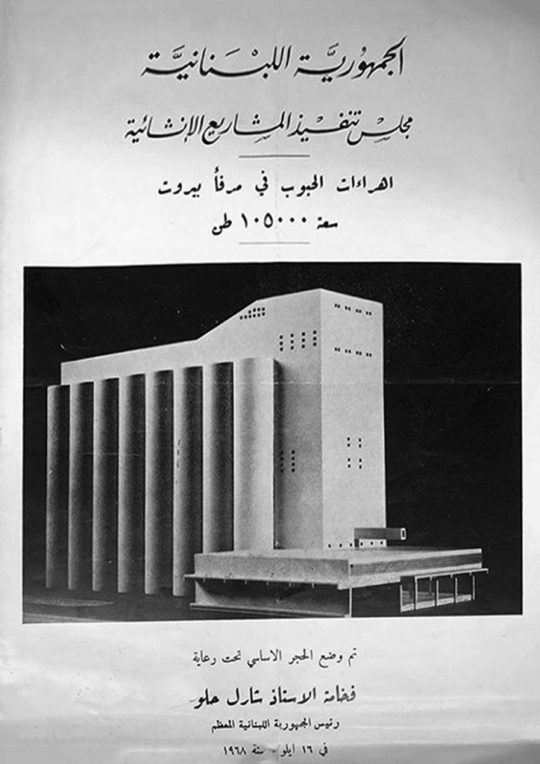

A short history of the Beirut Grain Silos, site of the catastrophic August 4, 2020 explosion. On July 30, 2022, the neglected silos finally collapsed.

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

UNPACKING THE ARCHIVE: THE SECOND INTIFADA – TWENTY YEARS ON

Screening Online June 9- 12

RSVP at ArteArchive.org

The Second Intifada heralded a particularly fresh, urgent and experimental approach to filmmaking, in tune with the uprisings to which it contributed. Working at a distance from both the main political organizations and, often, the aesthetic insistences of Global Northern art cinema funding, filmmakers took advantage of accessible technologies to forge new notions of freedom. The prolific body of work from this period does not just defiantly catalogue heightened colonial aggressions and appropriations, it does so with a wit and eclecticism of approach that touched diverse audiences at home and internationally.

The films in this program chart the violently altered geographies of expanding Israeli occupation: the pervasive military and civilian patrolling that sustain them, as well as Palestinian refusals of these imposed boundaries. Yet this work also questions modes of depiction that aim to straightforwardly document or witness. Instead, it often purposefully turns the recognizable and the everyday – along with steeped histories in how Palestine has been represented – inside out. In the process, these films question the capacity to capture the situation, or the territory, simultaneously maintaining a strategic tension between what remains globally familiar and the uniqueness of the circumstances in Palestine. An economy of style at once speaks of curtailment while always imaginatively bursting out of confinement.

Featuring works by Ayreen Anastas, Nahed Awwad, Enas I. Al-Muthaffar, Annemarie Jacir, and Larissa Sansour

Film Program:

Like Twenty Impossibles, Annemarie Jacir, 2003, 17 mins

A World Apart Within 15 Minutes, Enas I. Al-Muthaffar, 2006, 3 mins

Going for a Ride?, Nahed Awwad, 2003,15 mins

Pasolini Pa* Palestine, Ayreen Anastas, 2006, 51 mins

Sound of the Street, Annemarie Jacir, 2006, 3 mins

Not Just Any Sea, Nahed Awwad, 2006, 3 mins

Happy Days, Larissa Sansour, 2005, 3 mins

The screening will be accompanied by a recorded conversation between filmmakers Ayreen Anastas, Nahed Awwad and curator Kay Dickinson.

THE SECOND INTIFADA – TWENTY YEARS ON is curated by Kay Dickinson and presented as part of the ArteEast legacy program Unpacking the ArteArchive, preserving and presenting over 17 years of film and video programming by ArteEast.

Image Credit: Like Twenty Impossibles, (2003) Annemarie Jacir

THE SECOND INTIFADA – TWENTY YEARS ON | ArteEast

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Biennale Arte 2022 - Meetings on Art: What Could a Vessel Be?

The ninth event of the Meetings on Art at the 59th International Art Exhibition “The Milk of Dreams” (Venice, 23 April - 27 November 2022). One section within “The Milk of Dreams” is inspired by sci-fi author Ursula K. Le Guin and her 1986 essay “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction”, which thinks of the birth of technology and the writing of narrative through the metaphor of containers used for providing sustenance and care: bags, sacks, and vessels. Taking up this presentation as a point of departure, this panel reflects upon the metaphor of the vessel, asking what a vessel might be. With: Manuela Hansen, Christina Sharpe, Canisia Lubrin, Rinaldo Walcott, Wu Tsang.

Biennale Arte 2022 - Meetings on Art: What Could a Vessel Be?

1 note

·

View note

Photo

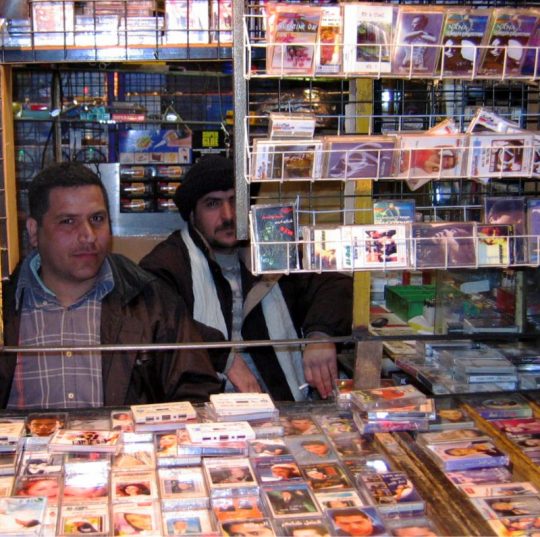

SYRIAN CASSETTE ARCHIVES

Syrian Cassette Archives (SCA) is an initiative to preserve, share and research sounds and stories from Syria’s cassette era (1970s-2000s). At the heart of the initial collection are hundreds of cassette tapes acquired by audio producer and archivist Mark Gergis during multiple stays in Syria between 1997 and 2010. The tapes weren’t originally collected with intentions of developing a public archive or forming a comprehensive overview of Syrian music. Instead, they reflect a period of personal research and curiosity, aided by connections made with local music shops, producers and musicians in Syria during the time.

The material is broad in scope – offering a small window into what could be found at cassette shops and kiosks throughout Syria during the 1990s and 2000s – a time when the country’s abundant retail cassette production was at its peak. The collection features an overview of musical styles from Syriaʼs many communities, including Syrian Arabs, Assyrians, Kurds and Armenians, as well as Iraqis displaced by sanctions and wars throughout the latter part of the 20thcentury. Amongst the tapes are recordings of live concerts, studio albums, soloists, classical, childrenʼs music and more, with special focus on the regional dabke and shaabi folk-pop music, performed at weddings, parties and festivities.

https://syriancassettearchives.org/about

28 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Day 4: AGHDRA. An excerpt from a film by Arthur Jafa. Film with introduction and conversation with Rinaldo Walcott.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

RIP Etel Adnan, 1925–2021.

Etel Adnan, To be in a Time of War (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 2005). Excerpt from page 1.

47 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Like physical photographs, we, too, shall disappear one day. Our urge to hold on, to prolong our lives and that of our communities, belongings, and symbols seems natural, and at the same time, illusionary. The digital realm is another form of preservation, albeit one that is equally ephemeral, in which new technologies render older iterations obsolete. Whether we realise it or not, we strive to create meaning to our objects, our desires, and our habitation by reproducing them, reinventing tools, and evoking narratives from diverse perspectives. What better way to live out our vulnerabilities?

Arab Image Foundation, Issue #2021.08

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

RECONSTRUCTING HISTORIES examines the role of the documentary in representing the Lebanese Civil War (1975–1990) through the experimental works of three important Lebanese post-war artists/filmmakers: Walid Raad, Jayce Salloum, and Mohamad Soueid.

The Lebanese Civil War officially ended after the 1989 Taif Accord, granting amnesty to those who committed war crimes, allowing these same figures to freely exchange their guns for a seat in the government, many of whom are still in power to this day. This raises the question: How can a country move forward when its past is unresolved and prone to repetition?

This policy of forgetting, and the failure of the government's handling of the nation's historical narrative, prompted a number of post-war artists - who were born during the 1960s and 1970s and grew up during times of war - to tackle the challenges of representing their recent past. These post-war artists used the documentary as a terrain to critically examine their history and how it was being represented.

In the experimental documentary Hostage: The Bashar Tapes, Walid Raad challenges notions of truth and historiography, bringing to the foreground the mediation of images in the construction of historical knowledge, questioning who has the right to shape historical narratives. In This is Not Beirut, Jayce Salloum highlights the crisis of representation - from reductionism to misrepresentation - conveying the impossibility of representing the overwhelming and complex narrative of the Lebanese Civil War. While the works of Salloum and Raad are crucial to addressing the issues and limitations of the documentary form, their role has been to point out, rather than fix these problems, reflecting the postmodern approach and its tendency towards aversion to "truth" in representation. In comparison, Mohamad Soueid’s Nightfall takes a subjective rather than conceptual approach, excavating fragments of Lebanon’s past from the ruins of memory.

Hostage: The Bachar Tapes, Walid Raad, 16 min | United States, Lebanon | 2001

This is Not Beirut (There was and there was not), Jayce Salloum, 49 min | United States, Lebanon | 1992-1993

Nightfall (Indama Ya'ati al-Masa), Mohamad Soueid, 70 min | Lebanon | 2000

RECONSTRUCTING HISTORIES is curated by ArteEast’s film curator Ginou Choueiri and presented as part of the ArteEast legacy program Unpacking the ArteArchive, preserving and presenting over 17 years of film and video programming by ArteEast.

RECONSTRUCTING HISTORIES—Unpacking the ArteArchive

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Beirut Urban Lab

The Beirut Urban Lab is a collaborative and interdisciplinary research space. The Lab produces scholarship on urbanization by documenting and analyzing ongoing transformation processes in Lebanon and its region's natural and built environments. It intervenes as an interlocutor and contributor to academic debates about historical and contemporary urbanization from its position in the Global South. We work towards materializing our vision of an ecosystem of change empowered by critical inquiry and engaged research and driven by committed urban citizens and collectives aspiring to just, inclusive, and viable cities.

Beirut Urban Observatory

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Commemorating the Beirut Port Explosion

Today, August 4, 2021 marks one year after the catastrophe of the Beirut Port Explosion that killed more than 200 people and left thousands wounded. Massive moral and material losses were experienced by the Lebanese people, Arab people, and all friends and loves of Lebanon around the world. A year after the explosion, the investigation committee did not arrive to a conclusion, the economy in Lebanon has severely collapsed and Lebanon is currently experiencing a suffocating political vacuum. On this sad day, we will not mourn Beirut, that is stronger than death and destruction, and that has gathered its wounds and risen to continue to play its role in raising the torch of freedom, creativity, art, and culture. On this sad occasion we stand to salut Beirut, the capital of Arab culture, presenting friends with testimonies of that dreadful day.

Commemorating the Beirut Port Explosion, Institute for Palestine Studies

6 notes

·

View notes

Quote

In the US state of Louisiana, along the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, a heavily industrialised ‘Petrochemical Corridor’ overlays a territory formerly known as ‘Plantation Country’. When slavery was abolished in 1865, more than five hundred sugarcane plantations lined both sides of the lower Mississippi River; today, more than two hundred of those sites are occupied by some of the United States’ most polluting petrochemical facilities. Residents of the majority-Black ‘fenceline’ communities that border those facilities breathe some of the most toxic air in the country and suffer some of the highest rates of cancer, along with a wide variety of other serious health ailments. They call their homeland ‘Death Alley’. Here, environmental degradation and cancer risk manifest as the by-products of colonialism and slavery. Sugarcane was historically the most dangerous crop to cultivate. To accommodate a negative demographic growth rate among the enslaved population, each plantation established at least one, and sometimes as many as three cemeteries for its enslaved population. The majority of these burial grounds were omitted from historical maps. Over the decades, all outward traces of many of these cemeteries have been erased. On rare occasions, cemeteries resurface – when petrochemical corporations break ground on new construction sites. In 2015, two cemeteries were uncovered during a survey for a proposed expansion of a refinery owned by Shell Oil Company. Four years later, four more cemeteries were located during the early stages of the construction of a new facility by the company Formosa Plastics. How might we recover the memory of the hundreds, if not thousands, of missing cemeteries at risk of desecration?

Environmental Racism In Death Alley, Louisiana ← Forensic Architecture

2 notes

·

View notes