Text

I took the picture above in December of 2020 in L Train Vintage’s East Village location. I remember entering the store on that cold, snowy day and being surprised by how packed it was; young adults, probably ranging from 16-28, bustled throughout the store looking for clothes. L Train was just one of many thrift stores in the area that thrived in the ‘vintage’ trend that had been set. This shift from the previously undesirable and economically accessible practice pf thrifting to one that had become fashionable and overpriced, mirrors the gentrification of the area. This is a topic we hope to touch on in our final project through a case study of Washington Square Park, which isn’t too far away from the store.

The objects in the picture themselves are stickers found on a basement wall of L Train. Their presence is not abnormal as stickers, formal and informal (such as graffiti sticky notes), are strewn across the walls throughout the store. What piqued my interest was the dichotomy between them. One sticker parodies the New York Police Department emblem, replacing the phrase “Police Department” with “Pricks and Dicks”. This seems to embody an anti-police, or at least anti-NYPD stance that had grown more prevalent in the wake of various instances of police brutality in New York (like Eric Garner in 2014) and nation-wide (like George Floyd earlier that year). In fact, I had attended police brutality protests not far from the store. Beneath this sticker was another one that represented a NYC gun club. Though not explicitly policing related, there is great overlap between those communities. Seeing these stickers together raised a few questions. What sticker came first? Was the placement of the latter an explicit response as I assumed or just a coincidence? Which side do the patrons of this store align with? Which side do the residents belong to ?

These ideas of commercialization at the expense of the marginalized, contrasting political views and policing in the Village all fit within the scope of our final project. Though we chose to focus specifically on Washington Square Park, these tensions are shared a few blocks over. It has become increasingly apparent that not all those who share this space share political views, whether it be about policing, profitization or public space. I am rather interested in seeing how these differences form along racial, gender, class and age lines, what compromises have been made and what the future holds for these shared sites of urban living.

0 notes

Text

Food Deserts in Queens, NY

UPDATE 12/14/21 - I just noticed that the FRESH zone layer was deleted from Arcgis, thus it appears in the picture and not the link.

Food deserts are a reality for many families, even in wealthy urban centers like New York City. Going from neighborhood to neighborhood, it is easy to see who has access to healthy food options and who does not. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) created a report regarding this problem, known as ‘food deserts. The report, titled “Characteristics and Influential Factors of Food Deserts” defines a food desert as a census tract that is both low-income and has low geographic access to food.

The study focused on specific calculations to determine poverty and access to healthy food. These determinations are often not accurate as they do not take into account certain diverse and variable situations. The census designation for low-income tracts is imperfect but accessible and reputable and so it was used for this map. However, the map utilizes the NYC Food Retail Expansion to Support Health (FRESH) zones to define access. These areas face a “ widespread shortage of neighborhood grocery stores providing fresh food options” The program offers economic incentives which “encourage the development and retention of convenient, accessible stores that provide fresh meat, fruit and vegetables, and other perishable goods in addition to a full range of grocery products” to mitigate this. As a local program, FRESH is likely more cognizant of New Yorkers' special circumstances that affect both affordability and access. Also, it is affirming to visualize these zones not just as an area facing hardship but as spaces worth active support and investment.

In Queens, unofficial systems often fill the void, from street vendors (often without permits) to community kitchens and potlucks. This food is filling, cheap, and sometimes nutritious. Another alternative is the deli/bodega which mainly functions as a place to get snacks, sandwiches, and convenience items. Unfortunately, they are some people’s main source of nutrition. Information on bodegas is hard to come by as it isn’t necessarily an easily defined category in city records but should be further examined concerning food deserts. Instead, the map outlines the influence of fast food by plotting all McDonald’s locations in Queens. These unhealthy food options primarily appear in low-income tracts and/or FRESH zones with a major clump in Jamaica.

Further research and visualization could expand upon this topic, perhaps showing the health effects these deserts create, the systemic racism woven into this phenomenon, and how transit can either bolster or diminish it. This piece, however, focuses on the economic aspects. As shown in the map, there is great overlap between low-income census tracts, FRESH zones which lack healthy, affordable food options, and the prevalence of fast-food establishments. More expensive, healthy food retailers often do not go into low-income communities as there is no financial incentive and US government subsidies are rarer and smaller than many other countries. It is important to recognize that FRESH and low-income areas don’t always interact. Race perhaps explains this divide; racialized neighborhoods are often perceived as unworthy of investment regardless of income. For example, there is a significant amount of economic diversity in the black enclave St. Albans, yet the entire neighborhood is FRESH zoned. Alternatively, many white and wealthy, gentrified, or formerly industrial areas parts of Queens like Long Island City, Sunnyside, and Woodside are also FRESH zones. These food deserts are likely because investments in these neighborhoods are just beginning and soon will be rectified. Anecdotally, I see a new trendy organic grocery store in LIC every time I go by.

Healthy food retailers operate in areas that provide the most profit that also meets racialized standards of urban desirability (not ‘ghettos’; ‘barrios’; or “Chinatowns”). That leaves a gap in the market that unhealthy food retailers, like McDonald's, take advantage of. In neo-liberal capital societies, access to food isn’t a right but is a full-fledged commercial enterprise.

Dutko, Paula, Michele Ver Ploeg, and Tracey Farrigan. Characteristics and Influential Factors of Food Deserts, ERR-140, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, August 2012.“Rules for

Special Areas.” Zoning Districts & Tools : FRESH Food Stores -DCP, https://www1.nyc.gov/site/planning/zoning/districts-tools/fresh-food-stores.page.

0 notes

Text

Written Critique: The Park Bench Is an Endangered Species by Jonathan Lee

The urban environment is fast-paced, filled with a flurry of activity. There is a beauty, and a necessity, to rest in urban spaces. Rest allows you to align yourself and start paying attention to those around you. Jonathan Lee’s letter of recommendation in The New York Times Magazine—“The Park Bench Is an Endangered Species” — may more aptly be described as a love letter to the park bench as it fulfills this need. The piece contextualizes all of the benefits of public seating with Lee’s personal experiences, both as a child in greater London and as an adult in New York City. Then, Jonathan Lee discusses the current trend of hostile architecture in city planning and the societal phenomena that cause them: commercialism, rise in homelessness and anti-homeless rhetoric. And while I share the author’s love of public seating and the leisure, community-building, and nostalgia it provides, the article would have been more impactful if Lee delved into the material importance of benches to marginalized groups in urban spaces.

The Letter of Recommendation section of The New York Times Magazine is dedicated to “celebrating the overlooked and underappreciated,” which, for Jonathan Lee, is the park bench. It is not presumptuous to state that park benches are overlooked in the urban environment; they’re common enough that they don’t stick out yet are not ubiquitous. Passersby will more likely be struck by the lush greenery surrounding them, fellow park goers, park activities, the city soundscape, or perhaps a city skyline in the distance. However, Lee reminisces about his close observation of benches during childhood trips and then states how this continued into his adult life. As he states in the article, “often a bench is the only thing stopping a name or experience from being forgotten. Park benches are excellent vessels for passing off precious information”. There is something quite beautiful in these plaques, whether in memoriam or as a declaration of love. It is the endowment of memory which connects to the broader theme of cities as a collection of stories.

Jonathan Lee believes “a park bench allows for a sense of solitude and community at the same time, a simultaneity that’s crucial to life in a great city.” This physical convergence of the public and private spheres of life is emblematic of urban environments where space, resources, ideas, culture are personal but shared. There have been many days where I retreat to a local park for some serenity and lose myself, in both times of quiet and humming noise. In those same outings, I have connected with strangers over glances, smiles, and conversations. The fluidity of this space is vital.

Yet, these manifestations of urban simultaneity are being taken away from their landscapes, either through outright removal, purposeful redesign to make them less comfortable and/or charging for access. Lee connects this to broader societal trends of privatization and commercialism and touches on how this measure is used to displace homeless populations. He is right on all accounts. As our society has drifted from more leisure, community centered to a hyper-productive, individualist model, changes have been implemented to support systems of capital at the expense of people and city planning is no different. In this field it has developed in the form of hostile architecture. Lee does a good job at describing his love for park benches, but in the face of this rising threat, it may have been fruitful to further explore the material benefits of the fixture as well. Tearing them down will displace many people without homes, it will make park spaces less accessible for those with disabilities. While true to the author’s experience, we must be wary that conversations around park bench removal and hostile architecture do not hinge primarily on these artistic and philosophical virtues but on the physical realities for the most directly impacted.

Lee, Jonathan. “The Park Bench Is An Endangered Species.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 12 Oct. 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/12/magazine/park-benches.html?referringSource=articleShare.

0 notes

Photo

Jane Jacobs in New York. Time & Life Pictures / Getty Images. Bob Gomel, 1963.

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Revisiting Jane Jacobs

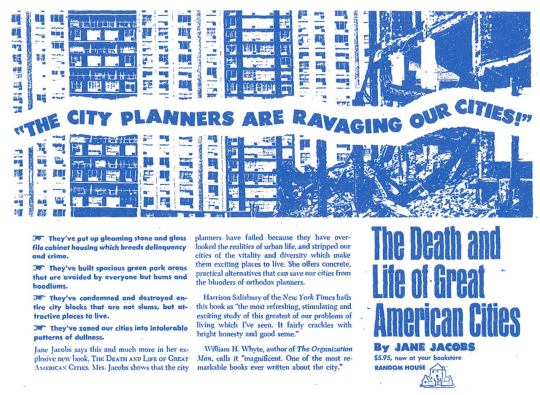

The graphic above is a book jacket of Jane Jacob’s famous book “The Death and Life of Great American Cities” which chronicled urban life in major United States cities and outlined Jacobs’ critique of urban planners of the era. Jacobs is often lauded as an important figure of urban studies. She led the charge against Robert Moses’ slum clearance plans of urban renewal, such as the Lower Manhattan Manhattan Expressway and the opening of a roadway through Washington Square Park. The practice of urban renewal was in full effect in the United States during the mid-century as imagery from ‘urban slums’ rocked the sensibilities of middle-America. It is also quite telling that this coincided with the Civil Rights Movements, so these concerns may have been racialized.

The jacket highlights a few direct quotes from the book, a general overview of the book and positive remarks from reviewers. Jacobs’ overarching claim, which visually takes center stage on the jacket, is that “The city planners are ravaging our cities!” . This language could be seen as sensationalist, but it would likely engage readers with varying levels of prior knowledge of or involvement with this phenomenon, which is likely what Jane Jacobs wanted. This book was published in 1961, in the middle of the grassroots organizing of Greenwich Village, Little Italy and Chinatown residents against Moses which Jacobs was a part of. Thus, this language was likely a conscious choice to incite audiences and persuade them to join the struggle.

The next portion of the jacket consists of additional quotes from Jane Jacobs’ book where she cites changes urban planners have implemented in the cities she uses as case studies. There is an intentional contrast in the language Jacobs uses to describe the developments (likely mocking the original planners’ descriptions) and that which she uses to describe their effects. For example, “Gleaming” housing which “breeds delinquency and crime”. Her take on zoning is especially interesting as she seems to denounce the monotonousness of this system which leads to “intolerable patterns of dullness”. This supports her broader point, that cities thrive off of diversity and community; this new wave of cookie-cutter development, neighborhood demolition and highway construction would ruin that.

That’s not to say that Jane Jacobs’ platform didn’t have faults. Her use of “delinquency and crime” is concerning because in the cultural zeitgeist those words often didn’t denote criminality but instead perceived criminality of people of color and low income people. The next bullet point continues this trend of chiding ‘the other’. Jacobs seems to purport that the recently developed parks are failures as they only serve “bums and hoodlums” but aren’t they also members of this diverse community Jacobs admires so deeply? Today, park space is a more beloved aspect of Greenwich Village but economic division remains. Now the park is an exclusive commodity where community members would like to exclude “bums and hoodlums”.

Jane Jacobs’s impact on urban planning cannot be understated. Her dedication to community organizing and maintaining the exuberance of urban spaces was vital. The tactics used by her and the Joint Committee to Stop the Lower Manhattan Expressway may be helpful for anti-gentrification organizers today. However, we must be careful to not fall into the same pitfalls of classifying community members as civilized and not. One of her proposed alternatives was an “eyes on the street approach” which scholars note may lead to profiling of ‘the other’ and mob mentality. Empowering community members this way, without accountability, training and seeped in socialized biases, often has dangerous consequences, like in the murder of Trayvon Martin.

Andersson, Johan. “‘Wilding' in the West Village: Queer Space, Racism and Jane Jacobs Hagiography.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 39, no. 2 (2015): 265–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12188.

Jacobs, Jane. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York, NY: Random House, 1961.

0 notes

Text

At the Altar of the Storefront Church

Religion and spirituality, or the lack thereof, have historically been very impactful in the individual lives of and interpersonal connections between people. Practitioners often sustain their beliefs through circumstances and active efforts to stifle them. Storefront churches such as Gethsemane Baptist Church are characteristic of that innovation and resilience. The photo which captures it is entitled “Gethsemane Baptist Church, 2097 Fulton St., Brooklyn, 1977”. It was originally taken on 35mm by Camilo J. Vergara in 1977, presumably while he was a graduate student at Columbia University. Though many people might picture churches like the grand and neo-Gothic St. Patrick’s Cathedral or even the newer megachurches like the Christian Cultural Center, Brookly, the ‘Borough of Churches’ is home to many small storefront churches. Gethsemane seems to be a small church which takes residence in a small part of a New York City block, nestled in between what may be a storefront and residential entrances. This suggests a very flexible, multi-purpose urban environment where business, home and church co-exist in close proximity. This unconventional use of space is often driven by economic necessity, New York City rents are exorbitantly high and most churches, fledgling or otherwise, cannot afford large spaces.

There is an older black woman in the photo, sitting in front of the church on a foldout chair, gazing watchfully into the lens. The pile and rack of clothes next to her can be presumed to be some form of mutual aid as churches are known to act in this capacity. This encapsulates the importance of churches like these in these communities. They provide a physical space for worship but also space community building; they provide resources like free clothes and food. This is rather powerful especially in the context of the austerity of the building itself, especially when compared to the aforementioned stately and wealthy peer institutions. There are perhaps some merits to this simplicity beyond financial feasibility. It is likely very similar to the architecture of the rest of the neighborhood and then perhaps more approachable and accessible. Consequently, it is very integrated into the neighborhood it is located in.

Throughout his career, Vergara seems drawn to these dichotomies of the urban environment. The derelict ruins of Detroit also hold some sense of untapped potential. This small building lacks the majesty of the cathedrals near the city's center but has high functionality by the nature of its location and integration into the neighborhood. The storefront churches are a wonderful example of a practice wherein marginalized communities assert their agency in spite of processes that mitigate their autonomy such as redlining and gentrification.

Citations

Vergara, Camilo J, photographer. Gethsemane Baptist Church, Fulton St., Brooklyn, 1977. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2020699444/>.

0 notes