Stories. Art. Reviews. Let's Plays. Other things, too.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Lord Alfred’s Homecoming

A historical treatise by Josephine Childress-Busey Published June the ninend, MMVII

St. Michael's Mount is a little island off the southern coast of Cornwall, on which a Catholic monastery was built sometime in the 900s. The following century, Pope Gregory guaranteed an indulgence to those who made a pilgrimage to the site, which led to the town of Marazion being built on the nearby coast.

In said town, on a muggy summer night in 1097, Alfred Codd came screaming into the world in a coating of amniotic jelly, and celebratory drinks were had among the local peasants. Legend has it that a sip of beer was given even to the newborn Alfred; if true, this answers a few questions about his life's deeds, but raises several more. He would leave Marazion at the age of four, his family being relocated to replenish the serf workforce at newly-conquered Rennes, but he never forgot his Cornish roots.

Codd grew up in a turbulent time for the Kingdom of England, for even as its foothold in northern France strengthened, ground was being lost on the isles of Britannia to a new wave of Viking raiders. His ambitions elevating beyond the mere plundering of English settlements for gold and slaves, King Snorri Ragnvaldsson of Norway was now dispatching warlords to claim Britannia's fertile land as well, rewarding those who succeeded with governance over the won territory.

One such Viking leader was Knut of Anslo. In 1113, embarking with a fleet of longships gathered from multiple coastal towns along the Skagerrak, he and his army rowed across the North Sea, then through the English Channel, and made landfall near Britain's southwestern tip. He swore on his arm ring (a bracelet traditionally worn by Norse pagans) that this land would be his, and when his raiders were successful in securing it, he became Jarl Knut of Cornwall. Finding St. Michael's Mount to be a fitting site for his throne, he enslaved the resident monks and repurposed their monastery as a mead hall.

In Rennes, a young Alfred Codd recieved this ill news. He simmered on it for years, pacified only by near-daily visits to the pub. Once he was adopted into the English nobility as a reward for his victory on the road to Caen, Alfred insisted upon having Cornwall's colors (a white cross against a black background) incorporated into his family's new coat of arms-- for, you see, he never forgot his roots. Nor was he of the sort to forgive.

Fortuitously, retribution was not far out of his reach; early in the year 1120, Lord Alfred was called across the Channel to do battle with the Norwegians once more. A collective of small earldoms swearing allegiance to the crown of Snorri Ragnvaldsson had perforated the isles of Britannia. Raids and even full-blown sieges were occuring with greater frequency across Enlgand and Scotland alike, and the kingdom of Wales was on the verge of collapse. Lord Alfred vowed that the English crown would reign supreme in Britain once more, and that the reclaimation would start with Cornwall, freeing the House of Codd's ancestral homeland.

Jarl Knut saw him coming. A well-placed spy in Rennes sent warning across the Channel, aleting the Norwegians occupying Cornwall to an imminent English attack. Knut consolidated his forces, gathering a total of about 830 Viking warriors in Marazion and sending 400 more to outposts along the southern coastline.

Lord Aflred made landfall in Britain quite some miles to the east of Marazion with a force of mailed knights, longbowmen and swordsmen that totaled a little over two thousand. The westward march to their destination would be a days-long slog through near-constant rainfall, and Jarl Knut laid multiple ambushes in the Britons' path. Yet Codd and his loyal subordinates were relentless. Despite the men lost each time, no Norwegian that lay in wait to hamper Alfred's army survived the Englishmen's wrath, and these victories spurred them ever onward.

On a rainy morning coming on the heels of a rainy night, Alfred Codd and his force regrouped outside of Marazion, reduced to about 650 men (mostly melee infantry), their tabards stained with mud and Viking blood, their chainmail rusting and their bellies growling, but their resolve little worse for wear. Inside the monastery at St. Michael's Mount, Jarl Knut heard a dire thunderclap and must have figured Thor was sending him a good omen, because he then casually ordered his second-- one Halfdan Nine-Fingers-- to assume command of Marazion's defenders in his stead.

Alfred's company charged forth into Marazion's streets, defying the armor that bogged them down in the mud and rain. Finding the opportunity ripe for a cavalry charge, Halfdan bade all of his mounted Vikings (a few hundred in total) to plow into what he assumed was a tired, vulnerable rabble of longswordsmen and archers.

Halfdan himself turned the corner to join his men and discovered, to his confusion and horror, that the aforementioned Norwegian cavalrymen were already decimated. The charge had broken against English shields. Alfred and his men clambered over the piled bodies of Vikings and their mounts as the few surviving horsemen fled in stark terror. Halfdan turned to make his own escape, but a yeoman's arrow found his back.

Leaderless, the remaining Norwegian forces fell back across the knee-deep strait between the Marazion mainland and St. Michael's Mount, so as to make a stand just outside the monastery. They hoped to use the strait as a chokepoint and rain down on the English with arrows, but did not take into account the superior range of their enemy's longbows, which thinned out their ranks before Alfred then ordered a charge onto the monastery grounds. By the time Lord Alfred captured the isle, his force was reduced to about 400 men, but the Norwegian defenders had been put to rout.

Inside his "mead hall," Jarl Knut listened as another thunderclap pierced the victory howls of his enemies. He was starting to think this weather was the omen of a different deity, particularly when Alfred Codd kicked open the door across from him and strode in, hair and tabard soaked but eyes ablaze with a terrible fury.

"This past year," said the English general, "When first I led the charge against Northmen, I expressed a degree of grudging respect for your kin. I reserve none of it for the Northman that now sits before me. For you walk on Cornish soil and call it your own, take Cornish monks and Cornish women as slaves, desecrate the house of God, and cower in it while your warriors fight and die!"

Knut disagreed. Accepting defeat, he stood up, arms spread out, and dared Lord Alfred to strike him down-- to send him to the halls of Valhalla, where he and his would drink in the company of the gods forever.

Alfred instead ordered him imprisoned. As the province came back under English rule, the Codds used their influence to ensure that the once and former Jarl of Cornwall would rot in a dungeon, denied the death in battle for which he had yearned.

And as Knut's long incarceration ensued, so did Alfred Codd's campaign to destroy the other Viking earldoms of Britannia.

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Nothing can make today alright, but maybe we can take some comfort from the brutal reality that the weak must make way for the strong. Evolution marches on. The scythe is remorseless. I hope the scythe's remorseless swing can bring some comfort to you all.

Excerpt from Alan Johnson’s eulogy to Gerrard

4 notes

·

View notes

Quote

In a world spinning as fast as the inside of Homebase when you've just had a go at a four-pack of Dulux tester cans, who is left to fight for all that is right and proper and good and leather and full of money and belonging to that teenager who doesn't look like he can handle himself?

Sir Digby Chicken Caesar

1 note

·

View note

Quote

For an anime show to totally, utterly refrain from the use of sexual humor or fan service would be Japan's most groundbreaking achievement in the arts.

Me on Discord the other day

0 notes

Text

Captain Yahyah Goes to Adrianople

A historical treatise by Josephine Childress-Busey Published March the sevth, MMIII

In 1182, the Byzantine Empire-- the final true remnant of the ancient Roman state-- fell as it became another stepping stone in Poland's rise to global prominence. Once an unassuming Slavic kingdom, Poland had spent the better part of the 12th century growing to encompass much of eastern Europe, Scandinavia, and then Greece as well. In an era where heavy cavalry was the deciding factor on many a battlefield, the Polish were fielding the finest heavy cavalry in the known world, and this translated to successful expansion. Once it was under their control, Constantinople would ever remain Poland's largest and best-fortified city, and it seems a commitment to tradition was all that kept the Polish from making the grand settlement their new capital.

That Poland was then able to maintain a peace with the Seljuk Turks-- who lived right across the Aegean from them-- for thirty-four years is a bit of a surprise. Admittedly, the Polish were a bit preoccupied with fighting Kiev and Novgorod during this time and the Seljuks had their own little border squabbles with the Khwarezmid Empire to deal with.

But in 1216, with English general Ralph Codd taking his infamous tour of conquest into Egypt and whispers of the Mongols' approach to the Near East growing more alarming, the Arab world collectively decided that Constantinople simply -had- to become a Muslim possession. This was stated to be because Allah willed it, but more likely because Islam itself faced an existential threat and was in need of a defensible position.

And so a holy war-- a "Jihad", the Muslims' equivalent of a Crusade-- was called, targeting Constantinople for capture. The Seljuk Sultanate of Rum eagerly answered, sending a good-sized navy toward the harbors of the city they knew as "Istanbul".

The fleet was promptly sunk to the bottom of the Bosporus Strait. It turned out, to the Seljuks' mild surprise, that Poland had a good-sized navy as well.

Though the Jihad was quietly called off, the Turks committed to their new war with Poland, as the humiliating defeat had not left them in a terribly good position to negotiate a ceasefire. Which brings us at last to the subject of this treatise.

The year was 1219, and a handful of further attempts at capturing Constantinople had proven fruitless. Sultan Malik Shah II recognized the city for the nigh-impregnable fortress it was; Poland had only managed to earlier capture it because a Byzantine guard neglected to shut one of the gates before the assault commenced. Malik devised a new approach in which his Turks would capture settlements to the north and west of Constantinople, cutting it off from the rest of Poland and surrounding it on multiple fronts. As the first step of this plan, Malik sent an army by ship to land on the northern coast of the Aegean and march northeast for a swift capture of Adrianople. One Yahyah Qutb was placed in command by the Sultan for this attack.

Two things were happening in Adrianople at the time. One is that the city was being governed by an adopted son of the Polish king, Janusz Wiktorowicz, who was fated to do great things later in life. The other is that an English diplomat, Roger of Flookburgh, was visiting Janusz on a tour of Poland's southernmost provinces. Neither man expected Roger to witness an attack by the Turks during his trip, so, naturally, at sunrise on the second day of Roger's visit to Adrianople, he awoke to find it under siege by the Turks.

With the city supplied enough to weather the siege for multiple months, Lord Janusz was unconcerned, and even invited Roger to accompany him to the ramparts above the southern gate for a view of the Seljuks' camp. As they took in the horizon together, they saw a single man ride forth from the gathered army, presumably to parley. Janusz ordered his crossbowmen hold their fire, and bade the Arab to speak. Roger's understanding of Arabic and swiftness as a scribe allowed him to pen a transcript of the Turkish captain's declaration:

"Infidels of Poland, look behind me, and there see the might of the Sultan-- one thousand archers of the horse, four hundred swordsmen of the horse, five hundred foot spearmen, and one hundred siege operators manning thirty catapults. I ask your people, once and only once, to lay down arms and leave Adrianople in peace, that they may live their lives elsewhere. If you should stay, your walls will be as dust and the number of your dead vast. My Sultan will have Adrianople, and Allah willing, the rest of Greece thereafter. For I am Captain Yahyah! Remember the name!"

Upon the conclusion of the Turkish leader's speech, Janusz Wiktorowicz broke into a laughing fit, as did a fair number of the Poles that were within earshot. Roger asked him what was so funny. "He said his name is Jaja," Janusz was recorded replying, "Did you not know? 'Jaja' is the Polish word for 'bollocks'."

Janusz then gave his crossbowmen orders to open fire on "Captain Bollocks."

Yahyah was quick to ride back to his army, he and his horse managing to avoid any injury from the flurry of bolts, and he ordered his catapult corps to begin their bombardment. The joke truly was on him that day, however, for the guard towers of Adrianople housed ballistae of considerably good range and accuracy, and Yahyah's catapults were all destroyed over the following hour. The city walls, though battered, held firm.

Still needing to breach the walls, the Seljuk captain kept his army out of range of the Polish ballista towers and bade his siege corps to procure and salvage wood with which more effective siege equipment could be built. Yahyah surmised that counterweight trebuchets could punch through Adrianople's walls from a safe distance, and prayed for but time to see them built.

Lord Janusz would not give him that time. By his orders, hundreds of Polish light hussars mounted up and rode forth out the southern gate, then began a frighteningly swift charge toward the Seljuk camp. Caught unprepared for this, Yahyah attempted to get his own horsemen to form up quickly enough to defend the siege corps, but it was too little, too late. The hussars plowed into the Turkish ranks, killing scores of their mounted swordsmen and foot spearmen. Only after they then chased down and killed the majority of the fleeing siege corps did Yahyah's cavalry archers finally arrive to the enemy line.

The Polish hussars sustained some losses to Seljuk archer fire but, their task finished, they retreated back behind the city walls. The moment of violence having passed, Captain Yahyah took stock of his situation and realized to his horror that the Polish had sacrificed surprisingly little to fully deprive him of the means to get past Adrianople's defenses... and kill a third of his army, to boot.

Roger of Flookburgh watched with awe from atop the ramparts as the Turks packed up and headed southwest-- back toward the transport ships they'd left on the Aegean seashore. Roger's written account of the battle gave England a bit of valuable insight into the battlefield tactics of the Turks and the uncanny resilience of the Poles.

Janusz Wiktorowicz would go on to become the king of Poland-- the first of a renowned bloodline.

Yahyah Qutb would go on to fill gravel pits at a mine in the arse-end of Anatolia.

0 notes

Text

The Anglo-Egyptian War Begins

Tales of the Crusades was a popular historical radio drama serial written and narrated by Dolph Segel that could be heard on EBC Radio 4 for much of the mid-20th century.

The sixteenth episode of the program, "The Anglo-Egyptian War Begins", chronicling the Battle of Libya fought in 1214, was originally broadcast on July 13, 1943, but was never rerun. It later came to light that the EBC had misplaced the tape.

A copy of this long-lost episode was discovered in a commoner's garage in New Londinium on February 5, 1999. The tape was badly damaged and only the final ten or so minutes of the broadcast could be restored. Below is a transcript of the restored segment.

{Static.}

{Calm, dour music plays.}

{Ambient sounds: Howling wind, hoofbeats on sand.}

DOLPH SEGEL: In spite of the week-long sandstorm, they ride west. Their eyes half-shut and faces covered in cloth to protect them from the searing wind, the Fatimids march slowly on through Libya, astride camel and horse alike, driven by duty to Allah and the Caliphate. Captain Ahmad, deprived of a clear view of the stars for the last several days and unable to see more than a hundred yards ahead, has been relying on the nearby Mediterranean coastline to know which way is west, for all is clouded by Saharan dust.

{Beat. Music and ambience continue.}

SEGEL: His is the first Fatimid army deployed by Caliph Al-Amir Bi-Ahkamillah against the bloodthirsty Inqulish, and will soon be the first to meet them in battle. The prospect is none too appealing, for Raluf Qad-- the Inqulish general-- is as fanatical a Christian as they come, and in the wake of his eastward march from Gibraltar, the Moorish nation already lies in ruin.

{Beat. Music and ambience continue.}

SEGEL: Ahmad must stop the Inqulish before they can reach Egypt, for if they should gain a foothold at the Nile River Delta and recover their strength there, nothing may be able to stop them from marching on Cairo, on Jerusalem, or even on Mecca. To halt this advance as far from Egypt as possible, Captain Ahmad has pushed his army on through the ungodly sandstorm that now rages in northwest Libya, sleeping on the saddle. Only just last night did they make camp for five hours' rest.

{Beat. Music and ambience continue.}

SEGEL: On this morning, after a few hours' trekking, Ahmad orders his men to halt, sensing something amiss. Carefully he listens, trying to tune out the howl of the ongoing sandstorm, and through it hears a faint, deep rumbling to the west. To ascertain who or what lies ahead, Ahmad orders five horse archers to advance, scope out the potential threat and report back. The scouts are apprehensive, but dutifully ride into the sandy murk.

{Sound effect: Louder hoofbeats, slowly fading out.}

SEGEL: It is not long before they can no longer be seen through the dust on the wind.

{The music fades out, but the sandstorm ambience continues.}

SEGEL: The rumbling halts. Minutes pass, the silence broken only by the storm.

{Pregnant pause. Ambience continues.}

{Sound effect: Hoofbeats and frightened Arabic shouting.}

SEGEL: At last, two of the scouts emerge from the storm to rejoin the Fatimid army, crying out in a panic. A long, oaken arrow has pierced the shoulder of one of them, and by the way its corresponding arm drooped at his side, Ahmad imagines he has lost use of it.

CAPTAIN AHMAD: Where are the others?

SCOUT: Dead! Two died before we could see who shot them. An arrow found the back of another as we retreated.

{Dramatic music plays.}

CAPTAIN AHMAD: Did you see who killed them?

SCOUT: I saw men in the armor of Crusaders. They wave crimson banners depicting golden lions, and white banners with red crosses. The number of their foot archers is beyond the counting.

{Beat.}

CAPTAIN AHMAD: The Inqulish. I thought we would not meet the enemy this soon, but Raluf Qad seems to have been pushing his men even harder than I mine.

{Beat.}

CAPTAIN AHMAD: They have marched more than halfway across Ifriqa to be here. Surely, the journey has left them exhausted. {He raises his voice to a commanding shout.} All mounted spearmen, form ranks and prepare to charge the Inqulish! We will rush their accursed archers and stomp them into the ground!

{Sound effect: Loud hoofbeats, gradually fading to nothing.}

SEGEL: After giving the command to charge, Ahmad watches as near ten dozen men-- some on camels, others on horses-- ride forth into the veil of dust with spears pointed ahead. Soon, the wind drowns out their hooves. Or is it the wind? Ahmad finds it unusually high-pitched.

{Sound effect: Quiet battle clamour.}

SEGEL: Nay; it is a chorus of soldiers shouting in the chaos of battle, of horses whinnying and blades crashing together. Minutes later, the shouts grow louder, as the thunder of hooves comes back, albeit mild in comparison to the initial charge.

{Sound effects: Hoofbeats, panicked Arabic shouting.}

SEGEL: Worried, Ahmad watches as something between thirty and forty mounted spearmen return from beyond the obscuring dust, howling with lost hope. Ahmad stops one of the routed camel spearmen from fleeing.

CAPTAIN AHMAD: Report! What has happened out there?!

CAMEL SPEARMAN: {He is audibly shaken.} The archers are guarded by dismounted Templars carrying halberds. We broke against their line! All the while, arrows rained on us... arrows truly beyond counting.

CAPTAIN AHMAD: Then we will--

CAMEL SPEARMAN: {He interrupts the captain.} We face demons, not men! If you will not flee, then pray that Allah will preserve you. I am getting to safety either way!

{Sound effect: A single animal's hoofbeats, fading away.}

SEGEL: Spurring his camel, the soldier disappears into the dusty fog to the east.

{Sound effects: Oncoming arrow volley, renewed panicked shouting. The music switches to a more panic-inducing track.}

SEGEL: And from the west, arrows begin flying into the bulk of Ahmad's army. Horse archers, foot spearmen and foot archers numbering just over a thousand begin to fret and waver.

CAPTAIN AHMAD: Horse archers! Ride ahead and harass their longbowmen while I get these men to regroup!

{Sound effect: Receding hoofbeats.}

SEGEL: The Fatimid cavalry archers ride west and disappear from sight, but the flurry of Inqulish arrows does come to a halt. With this moment of respite from the attack, Ahmad rides back and forth in front of the men, barking orders to reform their ranks. Minutes are spent on the effort, but the Fatimid army's morale seems restored... just in time for arrows to start raining on them again from the west.

{Sound effect: oncoming arrow volley, renewed panicked shouting.}

{Pregnant pause. The above music and battle ambience continue.}

SEGEL: Not one cavalry archer has come back from the Inquilish's position; Ahmad imagines they were finished off. Arrows shot from a greater distance than to which Ahmad's own archers can return fire come down on the Fatimids' heads, numerous as raindrops. Most of them hit nothing but sand, but it matters not that the Inqulish fire blindly ahead, so numerous are the missiles. One dozen after another, more of Ahmad's men fall dead with each volley. Since getting into whatever formation they were in, Raluf Qad's forces have slaughtered half of Ahmad's army without taking another step forward.

{Sound effect: Loud arrow strike, horse whinnying.}

SEGEL: An arrow strikes Ahmad's horse in the neck, and the animal falls onto its side. His left leg pinned by the weight of his dying mount, Captain Ahmad is unable to stand. At last, he hears someone barking orders in a language he does not know, and watches as his remaining men flee.

{Sound effect: Charging, shouting army.}

SEGEL: At last, Inqulish forces emerge from the cover of the sandstorm-- knights in red-and-white tabards on armored horses, chasing down the routed. In the throes of their victory, the Crusaders utter a Latin chant: "Deus vult! Deus vult!" Then, a man clad in full plate and draped in Inqulish heraldry approaches the downed Captain.

{Sound effects: Sword strike. Ahmad lets out an anguished shout.}

SEGEL: The last thing Ahmad ever sees is the the helmet-obscured visage of the enemy general as the latter drives a sword into his chest.

{Pregnant pause. All ambient sounds fade out.}

SEGEL: And the English army under Lord Ralph Cod continues on its warpath toward Cairo.

{Music ends.}

ANNOUNCER: You are listening to EBC Radio Four. For the next half-hour, we will be presenting a documentary on the Japanese colonization of Indones--

{Static.}

0 notes

Text

Snorri, Spear of Odin - Conclusion

In addition to being a veritable wellspring of charisma, King Snorri Ragnvaldsson, the "Spear of Odin," was an accomplished leader of warriors. After taking the throne of Norway and reinstating worship of the gods of Asgard, he heard objections and threats from the rest of Scandinavia, and this did not so much dissuade Snorri from embracing his people's old ways as it redirected his greedy gaze upon said neighbors.

Whilst continuing to send raiders to Britannia to bring in wealth and slave labor for bolstering Norway's economy, Snorri himself stayed in Norway to lead the bulk of his forces in his kingdom's defense from the other Scandinavian powers. He managed to dissuade Catholic inquisitors from formally accusing him of heresy outright-- by reminding them that attacking fellow Christians had been Magnus' crime rather than his own-- but the king knew he had to play his hand carefully. Too much aggression on his part would provoke the calling of a new Crusade and bring the wrath of most of Europe down on him, so he chose to wait for one of his neighbors to make the first move.

In the spring of 1103, Denmark did. Not with an army, mind you, but with a wave of missionaries. They proseletyzed in the streets for weeks, imploring the Norwegians to abandon their course and return to the gaze and favor of God. In this, Snorri saw naught but an opening to strike at his enemies' heart. His trusted agents went to work, and-- with careful placement of a Christian priest's corpse, a Norwegian jarl's corpse and a dagger in the former's hand-- successfully made the evangelists look like they were there to enact a dishonorable, hypocritical plot by Christendom to destroy his nation. The ruse was covered up so thoroughly that evidence of it would not be discovered until the late 20th century. Denmark's standing with Pope Paschal II was left sufficiently damaged that King Snorri was able to launch an invasion without third-party hindrance.

Thus, the campaign to unite all Northmen under one banner formally began. Over the course of the next fourteen years, the warpath of Snorri Ragnvaldsson took him all across Scandinavia, gradually putting Sweden and Finland under his rule.

The Danes, however, were more resilient. The year was 1117 when King Snorri's army at last came to the walls of Arhus, Denmark's capital city, after a lengthy and arduous push down the isles of Zealand and Fyn. Reinforcements arrived in the form of Vikings who were on their way home from a raid on Britannia but changed course upon hearing news of the coming siege from another longship; eager to take part in such a decisive battle, they made landfall in Jutland and marched east to join the main army. To see the raiders come to his aid without prompting humbled King Snorri and gave his men's morale a helpful boost.

Regardless of having his forces replenished and reinvigorated, an equal number of men waited for them atop and within Arhus' walls, all fueled by desperation. Snorri and Denmark's monarch, King Niels, agreed to parley before the assault. Niels' personal scribe was on hand to record their conversation, translated to English below:

NIELS: You have my thanks for agreeing to this meeting, Son of Ragnvald. Perhaps the Holy Spirit yet softens your heart, if but a little.

SNORRI: On your throne, there once sat a man named Ragnar Lodbrok-- a strong leader and peerless warrior. You, Niels, are no Ragnar Lodbrok... but you have been fortunate to find me in a good mood. Speak your piece.

NIELS: Denmark stands on a precipice. Most of my earls have perished, and all that remains of our royal blood is either within those walls or standing before you now. It may well fall, should we fail to find an agreement at this hour. Yet I imagine this is no concern for you.

SNORRI: Nor should it be for you! Denmark's defenders have fought well in this war, and in Odin's presence are not ashamed. Soon, the remainder of your warriors shall join them in Valhalla's halls-- as will their king, should you take up blade and shield alongside them.

NIELS: Leave that pagan claptrap out of this, and listen to me! My kingdom is all but destroyed, but it has regained the Pope's sympathy as a result. Do you understand what that means? You have nothing to gain by snuffing out what remains of Denmark, but everything to lose. Keep what land and riches you have claimed in this war thus far, if you must. I ask only that you give us peace.

SNORRI: Very well. You will have peace. After sorely grieving me by sending agents after me and my jarls in the guise of priests of your god... after cheating my nation out of some of its treasury the last time you approached the negotiating table, only to slaughter defenseless Norwegians the next day... after leading half my standing army into a dishonorable ambush at Fyn and slaying them to the last man after they'd surrendered... and after insulting me today with this petty hypocrisy in the wake of all of your actions... I shall give you and your Danes the peace of the grave.

NIELS: You fool! Stop walking away!

Snorri opened the subsequent battle by having his catapults bash open the gates of Arhus from afar. Scores upon scores of Viking infantry poured in with unholy fervor, meeting Danish forces in a bloody melee near their garrison. Despite the aid of King Niels and his personal bodyguard of war clerics, the Norwegian charge could not be held back. Within the first hour of battle, the king was slain, and a wedge of Norwegian footmen had been driven into the Danish line, killing over a thousand of the latter.

Horrified but quick to act, a Danish captain of unknown name assumed command of the men in Niels' place and bade them fall back to where one of the main roads opened into the royal castle's courtyard-- as good of a choke point as they had left-- and the defending army made a final stand there. The Norwegian push to take control of the city center was slowed, but remained relentless; for all the Viking bodies that piled up in the choke point, they kept coming. At last, though, Norwegians started entering the courtyard from another road, allowing them to flank the Danes and crush them. What remained of the nobility in Arhus capitulated not long after.

With that, the Jutland peninsula had become Norwegian territory, marking the end of Snorri Ragnvaldsson's conquests. Being connected to mainland Europe, Jutland made a fortuitous staging point for further Viking raids into Germany, Poland and English Normandy. Bands of Norwegian raiders would remain a considerable thorn in the side of Catholic Europe for half a century thereafter.

0 notes

Text

Snorri, Spear of Odin - Part 1

A historical treatise by Josephine Childress-Busey Published February the one-threeth, MMIII

In 793, the island monastery of Lindisfarne in Britannia was pillaged by men from across the eastern sea. To the Catholic monks residing there, the attackers seemed like agents of Satan-- wild, merciless, and willing to commit any act of blasphemy in the pursuit of riches. So began the first age of the Vikings, pagan warriors and explorers who sailed from the realm of Scandinavia on distinctive longboats to see the wider world and claim its riches... or die honorably in the trying.

In three short centuries, they left an indeliable mark on the world. Signs of their former footholds still linger on the Britannian isles, northern Europe and Asia, and even on the east coast of what is now the United States of Apacheria. Lands, kingdoms and noble families were named in their honor. Many in Western Europe can trace their ancestry back to this first Viking wave.

By the turn of the 1000s, the Viking raids had mostly come to a stop, and the kingdoms of their northern homeland were Christianized. Many thought that was the end of it-- that with Scandinavia integrated, the Catholic world could safely focus its concern on the Muslim caliphates growing across the Mediterranean.

Then a Papal bull came out of the Vatican announcing the immediate excommunication of Norway, and everything went down the proverbial drain.

Pope Paschal II, in either the bull itself (issued in the summer of 1102) or any public statements, never gave even the vaguest rationale for this. King Magnus "Barefoot" Olafsson of Norway had spent a significant portion of his reign so far on a series of invasions into the Britannian isles-- home to multiple Catholic kingdoms-- and one might speculate that this aggression provoked the Pope's ire. Magnus, himself a devout Christian, denied this vehemently and insisted that all of his endeavors had God's approval.

The excommunication threw Magnus's subjects into social turmoil. Many Norwegians feared divine punishment was at hand. Others, however, took to rejecting the Christian faith in protest. One Snorri Ragnvaldsson was part of this latter camp, and went as far as to openly embrace the pagan beliefs held by their ancestors, provoking accusations of heresy.

As chaotic riots took hold of Norway, only one notion united the people: Disdain for King Magnus Barefoot. All saw him as a hypocrite, carrying on the raids and conquests of yore whilst proclaiming piety to a god that abhorred the Vikings' actions. This, Snorri seized upon while leading protests. Gradually, his words grew bolder, proclaiming that if the god of Christendom has indeed abandoned Norway per the Pope's decree, then Norway would have to turn to other gods. King Magnus's power and influence shrank by the day as Snorri's following gained steam, and soon the latter was being called the "Spear of Odin."

In the fall of 1102, Magnus Barefoot and his family disappeared amid a riot in the city of Borg and were never seen again-- possibly having fled the country in the face of his total loss of recognition as ruler. Snorri Ragnvaldsson took the throne bloodlessly, and with the blessing of a majority of Norway's populace. His first decree as the new king was to switch the nation's state religion to old Norse paganism.

That winter, in the Highlands of northern Britannia, a fleet of longboats larger than anyone had seen in centuries approached the mouth of the River Ness one snowy morning, and the city of Inverness was pillaged by savage, blasphemous warriors. When the invaders departed with gold, trinkets and slaves in tow, leaving the icy streets of red with Scottish blood, the consequences of Norway's excommunication became clear: A new generation of Viking raiders had emerged to terrorize western Europe once again.

Benefitting from improved farming techniques and healthy trade deals with Novgorod, Lithuania, the Kievian Rus' and even the Seljuk Turks, Norway had been enjoying a sizable population boom, which was now translating to larger bands of raiders than were seen in the previous Viking era. The profits from their hit-and-run attacks on English, Irish and Scottish coastal cities proved useful, for King Snorri soon found his nation on the defensive back home in Scandinavia.

Norway's close neighbors-- especially the kingdom of Denmark based on the Jutland Peninsula-- remained staunchly Catholic, and were eager to win the Pope's favor by crushing this pagan resurgence.

0 notes

Quote

Maybe he'll end up happy and successful and I won't. That would be typical. I do everything society demands and die in a ditch; he sits on his arse and accidentally shits a golden egg.

Mark Corrigan

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Barbarossa, the Last Kaiser - Conclusion

By 1149, Lafrancus I had spent most of his tenure as Pope so far watching Emperor Frederick of Germany attack one Catholic neighbor after another. The rulers of Poland and England had been guilty of the very same thing, more or less, as each fought their wars of expansion the last five decades, but what made Germany special among them was their delusions of being Roman, enabled by one of Lafrancus' predecessors. The Emperor had designs of conquering Rome-- of conquering the Papal States-- and Lafrancus would not have that.

Frederick Barbarossa was excommunicated from Catholicism on March the 12th, 1149, to which the Emperor reacted by appointing his own Pope. Pope and Antipope were quick to excommunicate each other, and the rest of the world was quick ignore the latter.

A little later in the same year, the Anglo-Polish Alliance was forged in the fires of mutual disdain. Even as Germany was trying to fight off the English on its western flank, it was still occupied with war at its eastern fringes against the Kingdom of Poland. Fighting on both fronts simultaneously might have been manageable for Barbarossa before this pact was made, but now England and Poland were sharing resources and strategic plans with each other.

Germany also faced problems from within in the wake of the excommunication. The grandmaster of the Teutonic Knights, Henry the Lion, chose this turbulent time to betray Barbarossa and try to seize the German throne at Nuremburg. He failed and was executed. Barbarossa saw to it that the Teutonic Order was fully absorbed into the Imperial army (personally installing trusted general Wilhelm Gottschnitzel as its new Grandmaster), but this much-needed addition to his military power was too little, too late. His "Holy Roman Empire" spent the following decade shrinking as England and Poland divvied it up between themselves.

England's first significant conquest of German territory was in capturing the city of Frankfurt, and while praise for Alfred Codd's leadership is due, the battle was mostly won via German incompetence. Out of sheer, determined self-delusion, the German men-at-arms stationed in Frankfurt convinced themselves that there was no need to actually man their ballista towers. They reasoned that as long as they held on to their courage, the spirits of their "proud Roman ancestors" would operate the ballistae for them. As a consequence of this, Alfred Codd's battering ram was able to reach the western gate of Frankfurt unhindered.

In 1158, an aging Alfred Codd won the final battle of his life by capturing the fortified city of Innsbruck. The Polish nobility congratulated Lord Alfred on an illustrious military career by bestowing on him a bejeweled chest said to contain the Holy Prepuce. Codd wasted no time with the ribald jesting, pretending to complain "I couldn't even wake up my dear Amelyn with this!" His Polish friends were amused. The Papal inquisitor that happened to be standing within earshot was not. Needless to say, Lord Alfred only barely talked his way out of trouble.

Alfred Codd retired to his birthplace of Cornwall, but his liver began to fail in the same year. His eldest son, Simon, answered the summons to his beloved father's deathbed with haste, arriving to Britannia within two weeks. He had expected Alfred to entrust him with command of his army with his last breath, as he had been groomed to that end all his life.

But just as a lifetime at the wine jug had claimed Alfred's liver, so too had dementia claimed his mind. His final words, uttered not long after Simon arrived to his side, were "You're not my son. Get out of here."

A sympathetic King Mark I promoted Simon Codd to the post instead.

Simon proved not to be too different from his father when it came to leading Englishmen into battle, but he was also good at striking up spur-of-the-moment alliances of convenience. Case in point: Simon convinced a band of Norwegian raiders to help him and his Polish allies in the assault on Germany's final stronghold in Hamburg in 1160.

Faced with three armies at their final refuge, Barbarossa, Grandmaster Gottschnitzel and the surviving German troops and Teutonic Knights resigned themselves to a glorious death in battle.

So it must have come as quite a disappointment that when the Polish settled in to occupy the captured city, they took Barbarossa prisoner instead. He was forced to bear witness as the curtains drew on the German state (and, in his mind, the legacy of Rome itself), and wasn't executed until after a year-long show trial. His body was stuffed in an inconspicuous barrel full of vinegar and left forgotten in the catacombs beneath the cathedral at Hamburg. No one knows where it is today.

And what of Wilhelm Gottschnitzel? There is no credible testament to what the man did after the fall of Hamburg-- only that he survived and escaped Polish capture. For years after, those dwelling in the new German provinces of England and Poland held on to a hopeful legend that the Teutonic Grandmaster would one day return to restore the Reich, but there are no credible accounts of the man ever being seen again.

One thing was certain.

The geopolitics of Europe had become much less complicated.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Barbarossa, the Last Kaiser - Part 2

On the day that Barbarossa commenced the assault on Wroclaw's western gate, Polish crossbowmen watched the German battering ram (constructed one day behind schedule) crawl toward them from the safety of the ramparts, and then shot it with bolts coated in burning pitch. Fire consumed the ram before it could reach the gate to start its work. Barbarossa and his army proceeded to stand around, feeling awkward.

At which point an army of 6,000 Poles arrived from the east (two days behind schedule), immediately to be reinforced by the 2,000 or so men of Wroclaw's city watch. The German emperor hastily roused his men back into action with a few paeans to the glory of the Reich and the inevitable downfall of the hated auslander, and they met the enemy with gusto. Barbarossa's force did outnumber Poland's by about 1,500, but this ended up being no advantage at all; a significant portion of the Polish forces were crossbowmen mounted on some of the finest steeds yet produced by Slavic husbandry. These cavalry marksmen were learned in a fire-and-retreat tactic that long ago had served the Huns well in bringing the true Roman Empire to its knees. Barbarossa's men had no strategic answer for this, and were put to rout.

The following year, 1142, saw Germany put on the defensive, forced to defend its eastern holdings from Polish invasion as opposed to vice versa. But where German forces failed so flamboyantly at conquering new territory, they were quite apt at protecting what they already possessed from the Poles, at least for the three years to follow. With matters firmly in the realm of a stalemate at the border with Poland, Barbarossa lost interest in the war and left the front to focus on administrative duties. He made Nuremburg the new capital city of his realm, set a fixed price on grain to foster population growth, mandated better defenses for the northern settlements to protect them from Viking raids, and occasionally remembered to put on his crown in the morning.

For all the embarrassment his first two military campaigns caused him, it was in 1145 that Barbarossa's nation truly started going downhill. That year, a diplomatic envoy from the Kingdom of England (which was by now in control of most of the territory that had once been France's) came to treat with the German king, offering mutual trade rights and requesting an exchange of map information. That England wanted up-to-date maps of the Holy Roman Empire made Frederick suspicious and paranoid, and after a few hours' musing, book-throwing, shouting at advisors and sulking, he asked for the English diplomat to approach him once more.

Barbarossa took the scroll on which was scribed England's proposal and threw it into a burning brazier, then handed the envoy a counter-offer to take back to London. It read:

Kaiser Mark, Though I rightfully think him a spy, I have mercifully allowed your deceitful knave of a diplomat to return to your realm of England with his life, that he may deliver my response to your transparent ploy to obtain maps that would aid you in plotting further subterfuge against my Reich. There will be no trading between our peoples. Not a single auslander shall be allowed through our shared borders. No Englishman shall desecrate Holy Roman lands with their filthy footsteps, be they men-at-arms, merchants, spies or honest diplomats. A zweihander to the neck of any who do so. I demand recompense for the time that has gone to waste in our exchange of words. In three weeks' time, an envoy of my own will come to the gates of the English city of Rheims. Your representative is to give him one hundred and sixty florins as a show of apology. If England fails in this, the true sons of Rome will do all in their power to ensure I see you kneel before me. -- Frederick, First of His Name, Holy Roman Emperor

Mark I of England reportedly grinned as he read what is now infamously known as the Hundred and Sixty Ultimatum. To put in perspective just how petty this demand was, one hundred sixty florins was barely enough money to cover the upkeep of a hundred soldiers for half a year. The German emperor was threatening to go to war over what amounted to kings a pittance. King Mark surmised that if Barbarossa was going to be -this- childish, then Barbarossa would have to treat with England's most childish representative. And so Mark called for Alfred Cod.

Receiving a missive from the king instructing him to make for Rheims and deliver the official response to the Germans on England's behalf, Lord Alfred reluctantly departed from the French war front, leaving it in another general's hands, and rode northeast with haste.

Alfred arrived to Rheims in time to join its city watch on the ramparts above its eastern gate as Barbarossa's envoy approached with a bodyguard. The English general declined to come down to the ground and shouted this spiel at the diplomat:

"I have here a missive from my king. It contains his official reply, and instructs me to read it aloud. It is dignified and most eloquent. Verily, Frederick Barbarossa expects the most solemn respect from us Britons... but he has done naught to deserve it, so if it is quite alright with His Imperial Majesty's envoy, I will paraphrase my king's sentiment instead: You and your foppishly-armored little entourage can sod off! If Barbarossa so lusts to see his own people's entrails spilled across the fields of his kingdom, then by God's will, England shall oblige! You are not holy. You are not Roman. And when we have finished with you, you'll not be much of an empire either!"

Alfred Cod then led his men in singing a rendition of the then-popular drinking ballad "Trust Not Those New Krauts Over There", during which the seething envoy turned to leave, his guards following behind.

War was declared the following day, and the Holy Roman Empire swiftly raised an army to assault Rheims. Lord Alfred repelled the siege in short order, and he estimated that Germany spent ten times the Hundred and Sixty Ultimatum's demanded sum of money to recruit and equip the army that had just broken against Rheims' walls, leaving him to wonder what Barbarossa was thinking.

In truth, all was currently going according to Barbarossa's plan. He had expected England to reject the Ultimatum and its most famous general to react with violence. In his mind, the rest of the scheme played out beautifully; he would coax further aggression out of the English until it seemed that the rightful inheritors of Rome's glory were under assault by their fellow Catholics. Pope Lafrancus I would excommunicate Mark I, bringing the rest of Europe down on England like starving vultures, and allowing Barbarossa-- in helping to defeat England-- to claim such glory in the eyes of the Christ-on-Earth as to be granted rulership of Rome itself.

There was but one problem with Emperor Barbarossa's plan.

Pope Lafrancus I was an Englishman.

0 notes

Text

Barbarossa, the Last Kaiser - Part 1

A historical treatise by Josephine Childress-Busey Published March the threeth, MMIII

During a fair chunk of the Middle Ages, there existed a geopolitical hot mess of princedoms and city-states in central Europe that tried its very best to present itself to the outside world as a unified kingdom. If one was to travel back to the era and ask this nation's loyal subjects, they would refer to it as the “Heiliges Romisches Reich", or "Holy Roman Empire".

Everyone else with half of a decent education, however, properly knew the place as "Germany".

How did the German people acquire their pretensions of being the successors to the Roman Empire of old? The short answer is that the Vatican crowned Charlemagne "King of the Romans" in 800 to snub Byzantium, the -actual- remnant of the Roman state, because it had a female Empress at the time and the Church felt that being a leader of Romans was strictly a boys' club. Upon being given this inch, the Germans took a mile-- much to the ire of the Byzantines and the bemusement of everyone else.

For most of its history thereafter, Germany proceeded to remain the geopolitical hot mess described above. But as the early 12th century progressed, news of what was happening in the wider realm of Europe gradually stoked the Germans' collective dread. To the west, a small and relatively new Christian kingdom founded by William of Normandy grew to encompass the whole of Britannia, and soon began greedily conquering swaths of France. To the east, more and more of the Slavic world was rapidly coming under the rule of Poland. To the north, Denmark fell to a re-paganized Norway, exposing Germany to the brunt of the Viking Resurgence.

The year was 1136 when a youthful Swabian of noble birth named Frederick came to prominence. Together with the recently-founded Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem-- alternately called the Teutonic Knights-- Frederick siezed the German throne at Aachen and quickly crushed any of the princes who dissented. On Christmas Day of that same year, he was crowned Holy Roman Emperor. Tapping into his people's fear and hatred of the other European powers that surrounded them, Frederick was able to foster at least -some- semblance of national unity among them. The new Emperor's volumnous, firey-red beard inspired a nickname among the Germans in the form of "Rotbart". The rest of Europe came to know him better by the Italian variant of the title, "Barbarossa".

Once secure in his power, Emperor Frederick's next order of business was southward expansion. For all his delusions of being the one to carry on the legacy of Caesar, Frederick knew the "Holy Roman Empire" would live up to its name slightly better were it to actually control Rome. And so he rose a great army at the city of Innsbruck for a campaign to that end.

This did not escape the notice of the Doges governing Italy's northern city-states; they had expected Germany to make such a move for decades. Uniting and sharing their military power, the Doges of Venice, Milan and Genoa founded the Lombard League, no more than a year after Emperor Frederick took power.

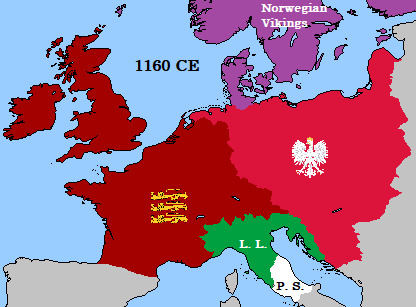

Pictured: The Empire and its neighbors at the time the Lombard League was founded.

Over the next two years, most of the other independent duchies between Germany and Rome would join the League; Bologna even went so far as to cecede from German rule and join this alliance. The stage was set for war.

And by the spring of 1141, Barbarossa was forced to admit he'd lost said war, having accomplished little more for the sacrifice of so many soldiers than to sack a few minor cities and lose the allegience of the Bolognese. Withdrawing his surviving men with shame, Barbarossa reflected on his reign so far and resolved not to be remembered for his failure in Italy. He needed to defeat someone to make up for it. He needed a more manageable enemy-- one that would not put up much of a fight-- and decided that Poland was that enemy.

The Polish were not amused to find Germans at the gates of Wroclaw that summer, especially since nothing had been done on their part to provoke the Reich. An exchange of letters ensued between Emperor Frederick and Wladyslaw II of Poland:

Kaiser Wladyslaw, I merely wish to inform you for the sake of politeness, if naught else, that an Imperial army far larger than the town guard of Wroclaw has the city surrounded and will be able to maintain its siege for up to four years. May its brave people go on to serve well as part of the glorious Reich. -- Frederick, First of His Name, Holy Roman Emperor

To the good King of Niemcy, It is noble of you to inform me of the estimated length of your present affront to my people of Polska. I find my spirits lifted by the news, for Wroclaw is well-supplied enough to withstand a siege for up to eight years. I have enclosed a small crate of kielbasa as a token of good will, Your "Imperial" Majesty. Perhaps, in sampling it, your people will finally learn what sausage is supposed to taste like. -- Wladyslaw II

Dear filthy, blasphemous auslander, Eight years, you say? Did you know, perchance, that it takes a couple of days at most for my devoted siege corps to build a battering ram? For your insults, all of Poland shall quake and kneel before the true sons of Rome. -- Frederick, First of His Name, Holy Roman Emperor

King of Niemcy, Do you know what takes less time than the construction of one of your battering rams? The answer is a single day's march, which is all that the six-thousand-strong reinforcements I have just dispatched need to reach Wroclaw. Perhaps you should attempt another invasion of Italy. They are quite preoccupied with laughing over the last time you were there, so you would have the element of surprise. -- Wladyslaw II

So began the battle.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Battle of the Road to Caen

A historical treatise by Josephine Childress-Busey Published November the ninend, MMVII

1119 is a year that many of my fellow historians look to as that in which the world's fate was forever derailed from its course. To assume this is to ignore the factors that enabled the brief battle fought on that day.

Personally, this scholar is more given to arguing that the true tipping of destiny's scales came in 1102. This was, after all, the year in which Pope Paschal II excommunicated the nation of Norway seemingly on a whim. Paschal never openly stated a reason for condemning the Norwegian people to spiritual damnation and would take whatever rationale he had to his grave. Whatever the case, the ripples started here-- ripples that, by the time they reached English-ruled Normandy, crashed ashore as a tsunami.

The news that they were no longer Christian in the eyes of the Christ-on-Earth rattled the Norwegian people. Collective dismay hastily evolved into collective anger, fueling a nationalistic movement that saw the Norwegians embrace their pre-Christian traditions to set their identity apart from that of other European powers. Chief among these deviations was their choice to reject Catholicism outright and return to the old polytheistic beliefs of the Norse, wearing the derogatory term "pagan" as a badge of pride.

That winter, Norwegian raiders made landfall in Scotland by longboat for the first of many new pillages. The Vikings had returned.

For over a decade thereafter, the fruits of Norway's ongoing pillages fueled a war of expansion back in Scandinavia. Gradually, Sweden and Finland were absorbed. In 1117, forces under the command of Snorri Ragnvaldsson captured Jutland. This move had the dual effect of not only wiping the Kingdom of Denmark off the map, but giving the Norwegians a convenient staging point for raiding the Holy Roman Empire, Poland and northern France by land.

By this point, England had gained more territory on mainland Europe-- specifically, the county of Brittany that lay west of Normandy. A road running between the cities of Rennes and Caen became one of England's busier trade routes, so it should come as no surprise that a band of Vikings came along to prey on caravans along this road. Each time they captured a haul of goods, they'd keep the food and drink to supply themselves, send the treasures home to Norway, and feast in celebration until their fingers itched for another plundering. As the English nobles thought little of this problem in the grander scheme of things, this group of Vikings was able to keep up the profitable venture for two years, until a young English serf-- born in Cornwall but living in Brittany at the time-- roused himself from his drunken stupor to loudly declare that enough was enough.

His name was Alfred Codd, and he had no earthly idea what he was doing-- only that he was tired of bar brawls and pushing around wheelbarrows full of dung.

When spring came in the year 1119, Codd was successful in convincing the Earl of Brittany to let him levy and command a militia. He put out a call for able-bodied citizens of Rennes to defend king and country from the Viking menace... but less than a thousand answered, all desperate peasants like himself. Those volunteers with experience in hunting were equipped with a bow. The rest were armed with pitchforks. Their armor mostly amounted to padded cloth and leather vests, with the few available chainmail shirts being given to Alfred himself and some of the pitchfork-wielders. In total, around seven hundred men were put at arms-- four hundred archers, and three hundred "spearmen" (insomuch as farming tools can be treated as spears). Following the morning sun, they departed from Rennes through its eastern gate and started trekking up the Road toward Caen, certain that the Vikings would show themselves somewhere along the path.

English morale was low on the morning of April the sixenth, and it is little wonder, as Alfred woke up with a hangover only minutes before the fighting began, and his second-in-command had to remind him what was going on. Through a spyglass, it had been determined that the Viking band headed toward them numbered about one thousand, and consisted wholly of melee infantry and light horsemen with axes. After splashing some cold water on his face and having his second punch him in the face a few times to induce alertness, Alfred ordered the peasant mob into a formation; he told the archers to stand together in a short, broad column and instructed the "spearmen" to surround them as a two-row-thick box, then ordered them all to stand their ground.

On being told it would help the men's morale to say a few words before battle was to be joined, Alfred Codd spoke thus:

"Bah, my head rebels against me. Thank you for joining me, brave Britons. I'm told many a general likes to rouse his men before battle with some manner of lip service to God. I am not one of them. Instead I will pay lip service to Maggote, a fine barmaid here in Normandy whom I am proud to call the first person ever to punch me out cold. God's blood, what a woman. Would that she would join us today. Now, our foes are Norwegians who would see us dead and our treasures looted. I, erm... I respect the Vikings-- not for their violence or their heathen beliefs, but for their prowess and courage in battle, and the hardiness forged by the harsh winters of their homeland. It is a shame, therefore, that we must now fill them with pointy sticks. Still, I confess that my codpiece is tightening at the prospect. Is that a snake? A snake! Kill it! Kill the bloody snake! Wait; it's only a twig. Thank the Lord. What else? Remember to watch out for spears. Oh, shite, they're almost here. Hold steady, lads!"

Alfred's oratory skills would improve over time.

After delivering the above speech, he took up his pitchfork and joined the other "spearmen". The Vikings stopped on their way west when they noticed the English army standing on the road in formation. Confident in their ability to quickly do away with the rabble but with no options to attack from a range, the raiders charged forth.

Whilst Alfred used protests and threats to keep his infantry from breaking formation, the four hundred hunters began to let fly. Their accuracy was lacking, but by virtue of there being so many bowmen and a decent supply of ammunition being available to them, they filled the air of the battlefield with enough arrows that for some of them to find their mark was an inevitability. At least ten volleys were fired before the mounted Vikings could complete their charge, and by the time they did, a third of the raider band was already dead.

The Viking horsemen plowed into a section of the "spearmen" box, trampling over some, causing dozens of others to spend a few moments fleeing, and even wedging some ways into the archers' formation. But now these horsemen were surrounded. Horror gave way to confidence, the hunters nearest to the mounted Vikings drew clubs, and together with the pitchfork wielders, they crushed the cavalry. It quickly became clear that, given some time at a smith's grinder for sharpening, a pitchfork lent itself decently to killing a horse or forcing a cavalryman off his mount in a pinch.

Alfred was able to rally the mob back into formation, and the hunters continued firing on the approaching Norwegian footmen. A little over half the Viking band had fallen by the time its main bulk closed in for melee combat. Flanking the English proved futile; the box of "spearmen" surrounded their archer comrades on every side. The melee struggle was grueling, but the long reach of the Britons' pitchforks did prevent many Vikings from being able to get a solid swing in without being skewered, and the hunters carried on firing over the melee lines to kill more raiders that were waiting behind those already engaged in combat.

In the end, the raider band-- reduced to a fifth of their numbers-- gave in to survival instinct and was put to rout. Alfred Codd looked around to see many of his fellow peasants on the ground, bloodied and writhing. The victory would turn out to be less Pyrrhic than it seemed; among the many dozen injured, only two had actually died of their wounds. These numbers surprised Alfred himself, but not as much as his family's elevation to the nobility as a reward for his accomplishment that day.

"If this is to be my lot in life," remarked Alfred upon his appointment to the lofty position of a general, "then I will need a substantially larger codpiece."

Spirits were high across the French provinces of England in the wake of the battle, a minor triumph over the Viking Resurgence though it was. Yet Lord Alfred was scarred by it in more ways than one, and wrote as much in his personal journal:

I drink to the dead now, until I achieve a blissful stupor. Us suffering a mere two losses would be much happier news to me had those two not been my only friends.

Granted command over an army of professional archers, heavy infantry and horsemen, Alfred Codd was soon summoned across the English Channel to the isles of Britannia. The new wave of Vikings had brought the Kingdom of Wales to its knees, handed Scotland some grievous defeats and placed fortresses along the eastern coast of England. It was time to bring these isles to order.

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

I'm just gonna not deal with that. That's my favorite solution to any problem. It's like the classic debate of why measuring the position of an electron changes its momentum and vice versa; the only correct answer is to get drunk and set fire to things.

Gordon Freeman

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Crow T. Robot: “This is how blurry it looks when I try to put on your glasses, Jonah.”

Jonah Heston: "When do you do that?!”

Crow: “When you’re sleeping.”

Jonah: "What other things of mine do you try on when I’m sleeping?”

Crow: “That’s it; just your glasses. But you should know, I do smell a lot of your things.”

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Things I Learned About Medieval Times from Age of Empires II

Standard marching protocols of the Middle Ages demanded that an army walk together in a tightly-packed column at the speed of their slowest-moving man. Combat of any kind was utterly forbidden until the army reached its destination, and ambushes were to be blithely ignored.

During the Persian siege of a Japanese colony on the Yucatan Peninsula (c. 2003), the Japanese used massed trebuchets for defense, and laughed that no amount of micromanagement would allow those slow-ass war elephants to dodge flying rocks.

It was often faster to just build a new castle than to repair a damaged one.

The gentlest way to instruct someone in the art of war is to hammily yell step-by-step instructions at them in a thick Scottish accent.

Siege engines such as the trebuchet and ballista were fused with the souls of orphans sacrificed during Catholic mass. This enabled the machines to move around, fire and reload on their own. Battering rams were even able to talk.

Farming was a lot easier during the feudal era. Land that had been designated for growing food would instantly till itself. One then merely had to sprinkle about half a tree’s worth of woodchips over the land, and the desired crop would grow to maturity in a matter of moments. The only remotely time-consuming step of the process, in fact, was harvesting.

Aztec priests were able to convert Christian monks to Mesoamerican mythology by lifting their robes to flash them. Such converted monks would continue dressing like Western shepherds for a while, but upon picking up a sacred relic would quick-change into Aztec vestments.

Early gunpowder cannons were ridiculously effective at destroying battering rams… unless they were fired from the top of a watchtower, at which point it was tantamount to throwing packing peanuts at the ram.

The Mongols conquered all of Europe under Ogatai Khan. The influence they would have on the colonial powers is felt even in modern America, where victorious baseball teams customarily build mountains out of the skulls of their beaten opponents.

Elephants were still used for war by many civilizations all the way up to the 16th century. Only the Indians thought to have archers mount on them, but the Persians could train an African elephant to follow a general’s orders even without a rider.

The body of Frederick I of Germany, Holy Roman Emperor, is interred in the Dome of the Rock at Jerusalem—perfectly preserved in a barrel of vinegar.

The best visual indicator of a medieval empire at its height was the presence of numerous useless mining camps all over the place.

Until the 16th century, the single most common medical procedure, no matter the ailment, was to wave a shepherd’s crook in the air and make tinkling sounds. This was good enough to help a man recover to full health, even from the brink of death, in at most a few minutes.

It was considered poor form to lower a portcullis to crush even your most hated enemy. So if a city gate opened during a siege and enemy troops got underneath it quickly enough, they were free to pass through.

William Wallace’s Scottish forces won the Battle of Falkirk, and did so as easily as if it were a tutorial mission.

The final battle of the Anglo-Byzantine War (c. 2005) was won with almost no bloodshed. Byzantine peasants simply hoarded building materials and constructed the Hagia Sophia. The sheer magnificence of the new basilica caused the Britons to lay down their arms and admit defeat.

As long as they were paying attention, just about anyone could dodge a fired cannonball, unless the cannon was built in Spain or Portugal.

English yeomen could shoot from out of the range of any castle’s defending archers—a fact that made longbows one of the last words in siegecraft. Under a sufficient barrage of longbow arrows, a castle would crumble in a few minutes.

The secret of Greek fire was leaked from the Byzantine archives sometime in the 600s, and it quickly became a staple of naval warfare all over the world. Even the Aztecs were already using it by the time Cortes showed up.

Persians were pathologically unable to recognize Scythians as enemies. Scythians were able to tear down Persian cities and slaughter their populaces while facing absolutely no resistance.

Guy Jocelyn prophesized the anointing of the late Joan of Arc as a saint several hundred years before it happened. It has even been credibly suggested that he foresaw it after he died.

It was frequent for an entire formation to break apart and spread itself all over the battlefield trying to chase down a single scout.

A predilection for wearing plaid kilts is a popular misconception about the Scottish people. In reality, they donned pantaloons with clownish vertical stripes.

Peasants were very polite. They were willing to take an alternate route around an entire forest or wall rather than get in someone else’s way.

The Vikings did have horns on their helmets, but you had to look really close and squint your eyes a bit to see them.

The Goths adopted an intricate new army composition in the High Middle Ages that consisted of huscarls, huscarls and more huscarls. Once they had this convoluted strategy fully worked out, there was virtually no battle they could not win.

As soon as the Roman Empire fell, javelin-throwing skirmishers suddenly became the bane of anyone that wielded a bow or crossbow, including the sort of horse archers that used to hand Roman skirmishers their arse.

No force in western Europe was more terrifying than a mob of Spanish villagers. Each one could endure being blown up by up to four suicide bombers and still be well enough to mockingly flamenco-dance away.

The Viking national anthem consisted of a single sour note, played on a horn for roughly two-and-a-half seconds.

A transport barge roughly twice an elephant’s size could carry as many as twenty elephants.

The amount of wood in a single oak tree was sufficient building material for two whole houses. The secret of such astounding efficiency was lost upon the advent of the Renaissance.

Poland never existed as a nation during the Middle Ages, but several nations that are not Poland fielded winged hussars as scouts and light cavalry.

By the time Attila came to rule the Huns, the Western Roman Empire’s architectural style was startlingly similar to what the Ottoman Turks would build about nine hundred years later.

The Mongols improvised with siege towers, far more often using them as APCs than as a means to get troops onto city walls. When fully loaded with infantrymen, a Mongolian siege tower could outrun a galloping horse.

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I felt secure in the demagogic wisdom of my early thirties. I believed that I had already beheld true madness. The alien sequence from Life of Brian. The Great Horned Rat declaring Slaaneshmas to be “fucking dead-dead.” The whale-shaped drive-thru speaker asking a fat little luchador to chop off his own legs. Real life people actually believing homeopathy works.

Naively, I assumed myself conditioned to endure anything insane without batting an eye.

...and then I watched Bravest Warriors’ season 2 opener.

1 note

·

View note