Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Extracting Global Blackness

West Papua, Indonesia has been identified as a critical nexus in the rapid development of what Is called, low-carbon extraction, i.e. the mining of lithium, cobalt, manganese, nickel, and rare earth metals. This takes place in a region that has recently witnessed a marked exacerbation of long-term political conflict associated with controversies over adherence to international provisions for a referendum on self-determination established in 1961. In the subsequent decades of Indonesian annexation and rule, a period marked the substantial and growing extensions of military administration despite the veneer of governmental decentralization and affirmative action, Papuans have become a minority in their region and subject to massive expropriations of land for mining and corporate agriculture.

There has been a massive inward migration from other parts of Indonesia, including from Eastern regions, which share many religious and ethnic features of the indigenous Papuan population. In the major cities of Sorong and Jayapura there is an intensive struggle underway for cultural, religious and racial dominance of the critical processes of urbanization, with a degree to which several key observers indicate the immanence of new waves of repression and insurrectionary violence. The Indonesian military and police, in the form of a multitude of command structures, continue their penetration across the sectors of Papuan everyday life, becoming the major administrators of infrastructure and social development.

Long-term balances in land disposition, inter-governmental relations, and social composition are being rapidly upended in the investment in expanding urban areas, skewed to enhance the political, economic and social power of inward migrants. Time is quickly running out to ward off developments that are aimed at undermining the residual authority of civil administrations largely populated by indigenous Papuans and to effectively “divide and rule” nascent but culturally powerful everyday coalitions amongst a heterogeneous and increasingly self-identifying “black” population, made up of Papuans, Ambonese, Timorese, Kei, and Alor.New infusions of global finance aimed at expanding and securing extraction, creating new high capacity urban enclaves in cities to the marginalization of local black residents, and severely restricting available spaces for political contestation, cultural expression, and circulation of information constitute the key elements of an explosive situation in the making. While the Indonesian military may indeed be capable of suppressing disorder, completely colonizing the spaces of production, and rendering unviable any real opportunities for a distinct Papuan nation, the implications of more heavy-handed control will inevitably ramify across the Moluccas and Nusa Tenggara Timor, with their own long histories of internecine conflicts and now rapid appropriations of land for low-carbon extraction.

Here, spaces of everyday cultural interchange amongst “black youth” in Papua’s largest and rapidly growing city, Sorong become particularly important. Hip hop, plastic and theater arts, church mobilizations, after school study groups, and civil society sponsored local environment management initiatives are bringing together youth from “Melanesian” (black )rooted ethnicities that constitute a majority of the city’s inhabitants in relationship to growing numbers of inward migrants from Java and Sulawesi. A multiplicity of cultural practices, drawn from youth, church, civil society, and local government initiatives, consolidate to strengthen the commonality of a working “black identity” that might attenuate the cultural and economic dispossessions underway, provide new platforms for municipal democratic participation, as well as mitigate the intensity of the competitions among religious institutions underway—competitions that open the way for increased military penetration in everyday life.

West Papua as an epicenter of the remaking of Eastern Indonesia through new mechanisms of extraction and displacement demonstrates then the ongoing struggles between the enclosure and expansion of blackness, both as a locus of repression and an instrument of new territories of operation.

1 note

·

View note

Text

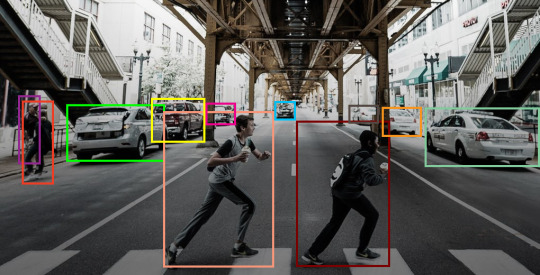

Detection

Detective Agency

Detection now plays an increasingly important role in our lives. The capacity to move, circulate, restore familiar patterns of work and sociality depend on the capacities to detect the presence of viruses, to detect trajectories of transmission, and surges and flattening of curves. The substantial elaboration of surveillance apparatuses is now well underway.

But there are also other more minor or subtle matters of concern when it comes to detection. These are about not only how present conditions are read in terms of detecting trends and patterns, but also the ways in which people detect themselves in a cascade of reports, stories, and analyses. How they see themselves a part of or apart from particular renditions of reality. There are those who detect that this crisis is a definitive crisis, that from which the once normal can never be restored, that is the harbinger of a new world and economic system. There are those who experience this time more cyclically, who detect the return of conditions that they already experienced some time ago, that reset the game, that wipe out all of the activisms and efforts of decades or a generation.

For example, many progressive activists who have worked with poor communities and social justice issues detect the present conditions as a return to 1998 and the end of the New Order regime of Suharto. All the work that had been done to strengthen the capacities and livelihoods of low-income settlements, to build new civil institutions is detected to have now largely been undone in a matter of weeks. On the other hand, decades of activism in India aimed at making the state assume more responsibility for ensuring the social welfare of the majority suddenly materializes in a substantial program of food and income support but in a context where many of the intended beneficiaries have at least momentarily disappeared from view. The practices of opacity that enabled many to secure livelihoods under the radar now complicate the ability of the state to reach them. Here, detection becomes an intricate game: the need to be fed but the need to avoid capture.

These conundrums are set within a larger game of contestation about ultimate values—the exigency to live versus the exigency to be free, reducing detection to all kinds of exhausted binaries, or at least arguments about proportionality. What proportionality is proper for what kinds of populations? Should those whose livelihoods are dependent upon day labor, hawking, waste recycling, artisanal factories, and marketing be forced into more extremes of impoverishment in the interest of reducing infection and morbidity rates? What degree of enforcement of spatial restrictions constitutes heavy-handedness?

A little bit of this, a little bit of that

Recipes for disaster would suggest a proportionality of ingredients, as would the rectification of disasters. But what if proportionality was not evident nor possible? What if it was unclear the extent to which existent realities on the ground were at one and same time self-destructive, virtuous, frivolous, necessary, generous, and manipulative? What if it were impossible to tell exactly what is virtuous or debilitating? In such instances everything become experimental, heuristic, a wager on a particular disposition. Detection stretches to enfold nearly impossible calculations as to the likelihood of viral transmissions in urban settlements difficult to lockdown, where interactions between exposures to various outsides, circuits of mobility, probability of contacts with those engaged in foreign travel, access to the tools of prevention, such as soap and water, are estimated as probabilities according to differing proportionality of contributing variables.

While it is clear that the survival should be extended wherever possible, that a right to survive should be embedded in every context of governance, just what constitutes that right, what secures it, what makes it possible in a given context may not entail either the possibility of working out proportions or that it even should. In other words, if initial responses to a pandemic require everyone to stay at home almost all of the time, what is the definition of home in which one must stay. If the outside is set off against the inside, to what extent are the dangers reversible, where certain dimensions of the outside are more than safe than anywhere else. If small factories in dense neighborhoods are being shut down because their production is considered inessential work, under what conditions and product lines could it be deemed essential, especially where these factories have always specialized in repurposing their tools and skills for other things. For all those petty traders who are taking whatever wares they have to sell to the rooftops, servicing the demand for goods issued from below, what happens to a refiguring of the street if these traders prefer not to return to the “ground. If youth still running in the thick lanes of popular neighborhoods force the elder authorities indoors, how might youth not so much take their place but rehearse their capacity, make something new in the here and now. The point here is that proportions depend upon the stability of their ingredients or variables, and that this may not be the time to insist upon such integrity.

We may face a situation where preferences as to who can move where will be issued on the basis of detailed profiling of an increased range of data, just as surveillance has been structured on the basis of probabilities that certain correlations of variables pose specific kinds of risk. Whichever way such expansions of data analysis may go, there is an expansion of a grid on which individuals are positioned. Critical decisions may be increasingly made, not on the basis of the basic grids of race, class, national origin, or age but on one’s positionality on a proliferating series of grids that represent a constant reworking of multiple variables that produces a score calibrated to particular tasks, settings, futures expectations, and needed functions.

When figuring doesn’t seem to matter

It is not so much that systems of racialization are upended, extended, or reinvented, but that a more intricate gridding system provides an illusory “real” that such racial or class distinctions no longer are the primary things that matter. We all know that black people are more vulnerable to bad outcomes in the current situation because blackness ramifies across all kinds of relative deprivations and over-exertions. But this “clarity” ends up always being denied, excised from the reigning proportionalities or registered only as an epidemiological fact.

Rather, such extensions of the grid are constituted to provide an assurance of equality, but an equality that loses the conventional terms of comparison, and importantly the public negotiations about what social (biological, historical) differences mean. Instead of society democratically working out what equality means, it becomes increasingly a matter of a “mathematics of singularities”. As a result, I may have certain privileges, access, and rights based on an algorithmically deliberated correlation of thousands of date points that generate a reality of my existence beyond any common vernacular. What makes me equal to others then is not evaluable in terms of what I have access to but that the terms of any decision are largely inaccessible to everyone.

Additionally, the very need for equality is obviated in the emphasis that for every moment in every place and for every function or activity there is a “right” person to occupy that moment. When algorithmic deliberations generate composite scores for specific requirements, they constantly run different correlations among different constellations of variables so that each variable does not possess a static or definitive weight, but is always recalibrated in terms of what at that moment is being compared. Thus the fact that I have a university education, or am a 68 year old white man, or that I have worked in 57 different countries in the world or have two daughters, etc. are variables without definitive weight, so that wherever I am positioned on an expanding grid, I do not know for sure exactly how much any single factor “counted” in terms of my positioning. There is a thus an equality of uncertainty that inhabits this system of expanding grids.

If there are any prospects then for equanimity, for a sense of collective action based on a fundamental negotiability of meaning of the very language we use in order to approach and represent each other, it may seem necessary to get off the grid, off the imposition of more intricate segmentations, cadastration, mapping, remote sensing, and enclosing. While the grid may have indicated a public realm, of a public connected to the grid of provisioning, manifesting an infrastructure of commonality, not only has many aspects of such a grid been overwhelmed, through disinvestment, surges of demand, privatization ,and its conversion into a speculative asset, but the logic of the grid itself stretches the “public” beyond forms of recognition that can be actively deliberated by residents at different scales. It is not just that public utilities and transport systems have been taken apart, but rather that infrastructures are sutured and articulated across territories in such variegated and consolidated ways as to render the terms and financial underpinnings inaccessible to the various forms of the public they are intended to serve.

Yet, at the same time are grids not even more necessary at this moment. As the state is mobilized or pressured into doing things it never considered doing—mass provisioning and income support, will grids not be needed in order to make more visible the populations that need this support? If the exigencies of everyday survival in desperate condition may propel vulnerable populations in greater levels of opacity, of operating under the radar, then do they not need to be coaxed back into view as the conditions to which they might be adequately serviced?

Again, here is the question of proportionality between visibility and invisibility, between knowing precisely what kinds of variables are contributing to particular situations and the need to keep things out of precise detection. And so perhaps we need new practices of detection, those that are able to bring things sufficiently into view in order to engage them but at the same time accede to letting them go, assuming other shapes and operations.

Gumshoes in invisible coats

Standard forms of detection always assume a truth that is to be uncovered, even if what is detected exceeds the existent terms of understanding. Something needs to be known. So it is not so much a matter of whether the truth uncovered is the truth, but rather the self-confidence of detection to generate a sufficient reason, to reiterate itself the definitive method for establishing the basis for decision.

But as Rob Coley illustrates in drawing upon the classic film noir, the detective is less interested in the “real story” than in trying to work out the unanticipated complications that the pursuit of the mystery has unwittingly thrown up. Detection seeks less to uncover complicity and conspiracies than to detach itself from the accruing story. It is more interested in the tactics of ensuring that things do not come to light, for to understand the crime to be solved means seeing how the crime has permeated into all aspects of living, and how the transparency of detection might leave nothing in its wake.

Of course this is familiar to us through Jean-François Laruelle’s notions of generic detection, where the objective is not to find the relations among things, not to put together all of the clues and various into a sufficient explanation, but to stay with insufficiency. Where the proportions cannot be worked out.

Why is this important? Because across urban districts around the world, thousands of stories of adaptations, risks, ventures, retreats, and retooling are emerging that are need to be told and heard in their own emerging terms. That need not be reduced to levels of compliance and suffering. That need not be reduced to the proportion of populations obeying orders. This is not a critique of pandemic policies or a valorization of the disobedient. But in the inevitable work arounds of spatial segmentations and categorization of whose work counts there are experiences that don’t fit into any yet common language, that need to be detected as blips, glimmers, and glitches, possibly emerging into some more elaborated vernacular, but also perhaps just disappearing without trace.

Detection here then is not the method through which individual and populations are subsumed into a system of proportionality—more or less healthy, more or less immune, more or less eligible, more or less valuable. Instead, it points to a space or composition capable of holding within it things and processes that may be related to each other, or not; where what something is may be multiple, but that it does not owe its existence to how it is positioned within a network of multiplicities, through which it accorded particular statuses and potentialities. This is not dissimilar to Fanon’s point that the wretched are an infection at the heart of colonialism, but an infection, that while being localized, is also immune to definitive detection.

Here, rather, is a detective that discovers within his or her “beat” a “real” that is “this one, right now, right here” and which has no definitive connection to anything else. But by doing so, such detection levels the playing field, renders something no more or less important than anything else, and thus avails it to unthought of (so far) courses of action. One could see detective work as a form of rendering, of making things (up), of making something available to a particular (wider) use, of putting things in people’s hands that they didn’t have before or couldn’t imagine using. Less uncovering than rendering, detection then is a way of keeping things moving along, of telling stories that extend a person’s relationship with the world, rather than detection being the grounds to legitimate the removal of persons from worlds.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Islamic Practices and Urban Transformations: Reinventing Lifeworlds

The Urban Institute and the Sheffield Institute of for International Development, University of Sheffield

June 18, 2020

The 21st century has seen a series of rapid shifts at a global scale in geopolitics and security, nationalism and border regimes and cultural and territorial representations with reference to Islam. Islam is swamped in so many attributions in these shifts—concerning studies of society, structures, space and lifeworlds--that typically generate homogenizing and reductive narratives often confined to elitist, dominant or ‘outsider’ epistemologies.

Islamic practices—and Islam’s sense of itself—must inevitably confront an obsession with “security”, as if Islam poses some univocal threat to sovereignty and democracy, that somehow it operationalizes of frictionless space of overarching religious loyalty. Given Euro-American responses to “9/11”, the 2003 invasion of Iraq and subsequent incarnations of so-called Islamist terrorist groups spanning multiple continents, shifts in the study of Islamic practices are conducted largely in isolation from longer-term historical patterns of migration, colonialities, trade relations, cultural legacies and so on.

Taking on Sabah Mahmood’s call to understand “intimate knowledge of lifeworlds that are distinct” (2011: 98), we will hold a workshop to seek ways of diversifying, decentring and contextualising ontological and epistemological understandings of how Islam in the daily lives of communities and individuals are understood in plural contexts. We aim to engage with multiple Islamic ontologies and epistemologically address a fundamental reconfiguration of social life underway across worlds and how they grapple with sustaining and remaking collective life.

The workshop will focus on hosting discussions to include a wider scope and variety of social science disciplines; initiate conversations around what kinds of platforms can be used to expand ontology and discourse regarding lifeworlds and places where Islam is a frame of reference and how this intersects with class, gender, nationhood, culture, sect and tradition in various contexts.

Funds are available to defer costs of transportation and accommodation.

Please email: AbdouMaliq Simone at [email protected] and Nabeela Ahmed at [email protected] for information and proposals for the workshop.

1 note

·

View note

Text

It’s Only Temporary (Part One)

“It’s only going to be temporary” is a phrase that I have heard repeatedly during the past several years. Particularly from young adults looking upon their present circumstances. While youth has conventionally been considered as a process of transition, as something temporary anyway, this process is prolonged for many in an anticipation of gainful employment, marriage and family or a sense of stability, an anticipation that may never end. Much has been made for a long time about the seeming intensifying temporariness of everyday life, and the way this word has been affixed as temporary contracts and labor, temporary friendships with or without benefits, even temporary autonomous zones. In an extensively urbanized era replete with the valorization of mobility and circulation and the ways in which any apparent stability seems tenuous because of the ways in which social and geographic positions are networked across an ever-expanding range of relations, what could not be temporary?

I want to briefly reflect on the way in which such temporariness inhabits the urban, may be the urban’s sole inhabitant, as the temporary itself seems to constantly unsettle what it means to inhabit, and how the cities and suburbs and peripheries and all kinds of strange urban formations should not be viewed as places to inhabit. Rather, they are rather what Karen Barad might call an electronic body all the way down, a condensation of dispersed and multiple beings and times, where future and past are diffracted into each moment—a body set lose as a trans*-mattering, constantly wandering through what might be or have been, regenerating itself through strange alliances. As such urban residents are always on the way to themselves already somewhere else.

Or to take Jenny Robison’s project of comparative maneuvers, where urban territories are forged through things shifting sideways, laterally, without subsumption or overarching frame, without settling somewhere. For, “to settle�� has always been excessively burdened by the imperial practices of the “settler” and his fascination, obsession in marking a story with a definitive beginning and end, a story from which to measure the worthiness of all others, their rights of use and potentials of self-making. Much of the urban today, however, wards off narration. Storytelling may continue unbated but what is told is less a story than a profusion of disconnected details.

Of course the obdurate abounds—all of those markets, shops and cafes that have barely made a few daily sales for decades; all the residential and commercial buildings that always have seemed to show signs of immanent collapse, all of those who have never extricated themselves from the same dead end job. Much is made about the relentless and accelerated transformation of cities and urban life, but from Mexico City to Mumbai large swathes of the city have barely been altered.

Yet regardless of empirical evidence the modality through which we tend to look a things seems to attribute a temporary condition to them, the sense that in a fundamental way they are already gone, past; that there is nothing about them that seems adequately prepared to survive through what is just about to arrive; that in the search for more intense experiences and exposures to the world that the ability to sense what is in front of us or where we are as somehow important or adequate quickly fades into a generalized restlessness. Even the notion of the “temporary” would seem to undermine its own meaning—for we recognize something as temporary in contrast to that which endures, sustains, continues. But for many in Indonesia’s black far east there is little recognition of continuity or of a destination to arrive to. In recent weeks I have been taking long ferry rides with youth as they make their way back and forth from Kupang—the main city of the East—in search of work on palm plantations in Kalimantan and Malaysia, gold and coal mines in Papua, the pearl beds of Alor, the oil fields of Aru, commercial ships from Makassar, agricultural processing and construction in Ende or Maumere, or low end jobs in Surabaya.

Most have not retained any positions in advance, and if they manage to secure some kind of temporary arrangement, do not stay at it for very long, for the working conditions are oppressive, the supply of potential labor voluminous, and the work itself it often pitched to fluctuating markets of demand. They rarely talk about where they come from or where they would settle if they had a chance. In this region of promiscous mixture the long nights on the ferry are punctuated by racial and religious anxiety, of the ways in which skin tone indicates a shifting barometer of proximity to increasingly precarious economic opportunity on the one hand and a tenuous rootedness to tradition on the other.

In a region where barter, piracy, mercantilism, and capital exchange on steroids all intermix more or less, race is a marker of who and what is made available for what. As few on these boats claim any capacity to manage their fates, nights of sugary coffee banter center on who is really Indonesian or not as if any had the faintest idea of what such a national designation referred to in the first place. At one moment they will vociferously complain about the enduring capacity of the Bugis to capture commercial markets, dominate the trade in every small thing, at the next moment everyone will claim to be Bugis themselves knowing about a deal that is about to go down, an opportunity that could make everyone rich for a few days.

Everyone sizes themselves against each other, men and women alike, although this is primarily a male world, with the women consigned to adjudicate disputes that threaten to get out of hand or who are the only ones carrying real things to trade. Yet most are also able to temporarily break through comparisons inflected by racial anxiety to offer everyone something, where they seem to hold nothing back in terms of places to stay, names of contacts, tricks to get by. To listen to their accounts is to enter a fray, a sudden whirlwind like those that often plague the boats traversing these seas, and the subsequent rash of cancellations and rescheduling.

For what is told is usually disjointed, an account begins in one place but without warning the scene switches seamlessly to another, plantations become brothels become churches become rigs, and so forth, and it is hard to keep track anything coherent. No wonder, would be the quick conclusion, that these youth are not getting anywhere because they don’t seem to know where they are at any moment or what they are getting themselves into. They barely seem to touch shore and are at sea once again, which is the literal situation for many. Like their forebearers they are most familiar with “slash and burn”, as they are not investing in long terms relationships but in maximizing this particular moment of contact. As such, it is hard to tell where these youth are actually coming from. Just as they continuously talk about something “out there” that will change their lives, when you ask where they come from, they point out across the sea and say, from “out there.’

Of course they all come from somewhere. Many are the offspring of long disappeared migrants, of reworked households from which they have been sometimes excluded, sometimes made unwilling centers of. They were sometimes the ones on whom extended family hopes were placed, ones designated not to work the fields, or those for whom fields were already overcrowded or fallow. Some were designated as those who could best “do without”—a parcel of land, a spouse, a normal future, so that meager savings could be applied to those seen as more vulnerable. Their strength was thus immediately converted to a deficiency in larger labor markets, in which they had only temporary footing—a little bit of driving, delivering, constructing, repairing, servicing.

Kupang, the largest metropolitan area of this East is full of young people with such temporary positions, waiting around, waiting to leave, then leaving. They deploy themselves as disposable income for tenuous and increasingly tense affiliations “back home” and beyond that are only partly familial, and entail complex relations of indebtedness among blood relatives, clans, local sponsors and authority figures—these the intricacies of communities hovering with uncertainty between the long-honed practices of bartering economies and the not yet fully instantiated economies of cash.

As retail and wholesale corporations increasingly dominate agricultural production locations and cycles all the way down, as large investors from Jakarta and beyond swallow up large tracts of land on and offshore in formerly remote locales, as the plantation system returns to consolidate individual landholdings, as already dry climates face further reductions in wet seasons, and as larger amounts of small scale agricultural production is left to older women, the stage is set for a preponderance of youth riding fast and loose on the motorbikes poverty no longer make unaffordable. For if your not riding the seas, your riding what passes for roads, sometimes with purpose, but most often without one.

In cities where the jobs of delivery are dependent on managing the mechanics of circulation, getting around is an intricate series of constant calculations always deliberated algorithmically in the imaginations of drivers that are buying time for their customers or making the sheer act of consumption possible. Algorithmically in the sense of various combinations of variables, impressions, hearsays, and shared messages that are reweighted in relation to each other, then applied to the question, “what should I do, how should I proceed?”

For, in many cities this kind of driving is done by marked bodies—those otherwise marginalized by virtue of racial or locational background, legal status, such as refugees and migrants, all of whose precarity cheapen the costs involved. Still this is the closest to stable employment many of these mostly young men will ever get. Itineraries thus are always subject to interruption—all trips between here and there are fraught with increased risks for specific bodies, where the specifics of their histories and aspirations are irrelevant to the fates to which they could be disposed.

Knowing that people have to move around, have to show themselves beyond the relative confines of safety in recessed neighborhoods, entire apparatuses function on the inflated prices of both survival and death that target such a showing. Extortion rackets, arbitrary detentions and executions, illegal detainment, shakedowns not only become purviews for criminal elements but integral aspects of official policing and municipal fundraising. So there is always a biomass available for being picked up, put over there, made to do whatever, and easily disposed of—creating an atmosphere in the midst of the urban poor where planning might simply be only useful as a recreational activity.

Instead of investing in the development of people’s lives as productive citizens, availed of a place from which to narrate a history of progression, of improved well-being, populations are “let go”, subject to what Ruthie Gilmore calls organized abandonment, their life-times freed up from definitive anchorage or accreted value, and made expendable, as currency to be spent, which in aggregate constitute a form of securitization, a constant stream of income available for expenditure, a wide open terrain of manipulations on what bodies can be used for, how they can be shifted around, all of which can be parried into claims of investment worthiness issued by elites and their nation-states.

Neferti Tadiar talks about the entrapment of populations having been convinced that becoming properly human is something worth pursuing, and willing to pay for. Residents have long been coaxed into jettisoning mixtures of jocularity, trickery, fast talking, inexplicable generosity, deft maneuvers, festivity and dissimulation in favor of a belief that propriety was attainable through considering one’s lifetime as a property to be cultivated, a value to be maximized. Never mind when teachers rarely showed up in classrooms, that the army milked every effort at entrepreneurial spirit, or that savings groups ended up paying exorbitant interest rates.

The urban poor are no longer reserve labor but indications of the capacity of states to move bodies around, keep them in line, kill them when necessary, and thus prove their creditworthiness on the international market. The refusal to invest in social reproduction, leaving the poor to fend for themselves now under conditions when fending becomes improbable conveys the willigness of nations to do what is necessary to guarantee the safety of foreign investment, to detach itself from its own coherence in favor of the machinic resonances of continuous incomes streams dutifully laundered. Life for many is what Neferti Tadiar refers to as “remaindered life”, that which remains after the pursuit of a normative humanity has been exhausted. As she points out, alternative ways of becoming human consist of tangential, fugitive, and insurrectionary creative social capacities that despite being continuously diminished, impeded, and made illegible by dominant ways of being human, are exercised and invented by those slipping beyond the bounds of valued humanity in their very effort of living, in their making of forms of viable life.

To mobilize even remote opportunities requires intricate forms of brokerage, lives subjected to intricate insurance policies that calculate the risks and attempt to circumvent them. Even for those riding the waves in Indonesia’s East attempting to escape all kinds of tedious obligations, they often end up owing far into the future, lives already mortgaged, forced to work backwards to pay off what they already owe. Here indebtedness seems far from temporary, that lives are rather locked into a set disposition from which there is no escape, except perhaps the literal taking on of more debt to escape that already accrued.

Under such circumstances what kind of story is worth telling? For these youth on boats, heading back and forth, they have little to carry with them but scenes of provocation, the way they push and pull at each other’s maneuvers. The ship may move ever so slowly, but in these long nights, they don’t sit still, they wander up and down every nook and cranny, they preach from tables, they sing local versions of Thai songs they have seen in videos, they demand each other’s attention, they hatch plots and schemes to take things weakly guarded, they talk about cousins and uncles who can do this and that. It is a thick web of complicities that can dissipate at any moment. Everything remains temporary.

0 notes

Text

Urban Human: a small treatise, part two

Entang Wiharo

Fields of Investigation:

1. Racialization, anti-blackness, and strange geographies

The urban human, in particular, wavers between three complicit versions of racialization—i.e. the consolidation of whiteness as the norm of humanity, the generalization of blackness as descriptive of the human condition, and the appropriation of blackness as its redemption. Blackness straddles these volatile divides, often attempting to “disappear” within vague spaces, futurist assemblages of ghosts, androids, gods, monstrous bodies, polyrythmic encounters. The Afro-future is a long-honed attempt to suture the human and non-human so as to circumvent all that has and is demanded of blackness.

If the purported nothingness of blackness is historically that vast chasm indifferent to human striving, that is the terror that would potentially immobilize any sense of free will, to what line is blackness kept if blackness does not line-up with any specific known category. For, it is in a world of its own ineligible from being a world. It is the nothing that must be kept close but away.

Urbanity built on anti-blackness keeps the expendable, the nothing, close as a constant reminder of what it is not, as something available to be operated on, lacerated, extinguished, penetrated. In doing so, racialized bodies are set at a remove, ineligible for the wanting and stabilities of that deemed normatively human.

But this calculus sets up a necessary inversion. For, what becomes removed is the spatializing of something that is not quite a world, territory, city, landscape or ecology—something else besides these things, yet close enough to being them to generate an incessant unease in our ability to secure any clear notion about what a world, a territory, a city might be. In other words, there is a modality of existence uninhabitable in any clear terms, yet which is lived in and lived with in ways that defy definitive judgement or assessments of viability. It is these zones zoned out of categorical policing that remain at a distance, the remainders of dispossession, and perhaps an important terrain for an urban human.

Entang Wiharso

2. Urban tissue as urban flesh

As Tom Cohen indicates: “The very thing that would universalize the prospect of a joint species perspective, “humanity” as the “humanualist” hominid that anthropomorphizes, guarantees the opposite: its fratricidal fragmentation—since anthropomorphism can only operate as an exclusionary usurpation. And it may reference what we take consciousness to be, without entirely reflecting whether “consciousness,” if definable, were necessarily hominidor might be generated and exceeded by A.I. networks.”

This does not mean that the dispensing with the human is the necessary precondition to enable a more judicious rendering of urban life. Rather is it possible to come up with a different sense of what universals might be? For example, the emancipation projects necessary to upend the dependency on subjected and subjectless persons in predominant reflections on the human might reiterate the importance of the “flesh.”

Here, flesh is that unruly particularizing that takes place within a seemingly featureless mass, and the mass transformed into individuals and particularities that cannot be legislated, cannot be rendered an object of law or discourse. This might reiterate the salience of the concept, “urban tissue”.

Andy Merrifield considers urban tissue “as fine-grained texturing, as a mosaic and fractal form that has some delicate content, some feel to it, something we can touch and manipulate in our own conceptual hands, think feelingly, as it were.”

It is the materiality of encounter among things, materials, and bodies. Each is articulated to each other in ways that exceed the capacity to map, measure, and account for their oscillating relationships. Tissue as in the push and pull of different practices of connection that simultaneously compete with and complement each other, not in consensus, but in cross-patterning of stitch and weave, turn-taking, and looking-out for that Toni Morrison attributes to quilting gatherings of women in her novel, Home. Survival means covering the angles, hedging all the different ways things can be disrupted, changed.

So tissue is not the seamless connectivity of everything. It is rather that which enjoins different forms of speculation, risk-taking, hedging, and shapeshifting. It is the quilting of seemingly contradictory ways of doing things. It is the texture of ambiguity, of not knowing for sure, of a willingness to go this way or that, of not knowing for sure that angle or the position from which one speaks.

Flesh perhaps then points to a more viable “human”. This is what Hortense Spillers would call the “zero degree of conceptualization.” It is the flesh that is exemplified within the contexts of black subjection, where particular bodies are read and governed as indicative of particular genealogies, functions, capacities and degrees of humanness. But these are readings, which at a level of the body’s fleshy substance, are, by virtue of the very act of being read, both inconclusive and insufficient.

Flesh finds itself in the middle of things, not as the mediator of pre-existent identities, but rather as a gatherer of details. Flesh lures the reader and then blindsides her at the same time; flesh exists to be read, but always read the wrong way.

To have flesh, then, points to the terrain of humanity as a relational assemblage exterior to the jurisdiction of law given that the law can bequeath or rescind ownership of the body so that it becomes the property of proper persons but does not possess the authority to nullify the politics and poetics of the flesh found in the traditions of the oppressed. … it translates the hieroglyphics of the flesh into a potentiality in any and all things, an originating leap in the imagining of future anterior freedoms and new genres of humanity (Alex Weheliye).

What is it that inhabits this flesh? How has the flesh acted as the scene of so many crimes, the rooting place of so many “potentates”, where bodies were forever indebted to the utter arbitrariness of authority? How is such flesh real? How is it more than its manifestation of conquest?

Any discernment of this possibility requires a particular methodology, what Achille Mbembe calls “clairvoyance”, a capacity to intersect the mobilization of both life and death, where each signals the beginning of the other, a starting point that returns each to the other and is, itself, an inexhaustible surplus. In situations that are seemingly devoid of human values and capacities, of bodies reduced to their flesh, what else does or can ensue in these bodies connection to a larger terrain besides bareness and precarity?

Here, it is important to look at emerging tissues of care, where providing care entails acts outside of labor. What are the ways in which urban residents, faced with rapid and substantial transformations in terms of where and how they live, piece together a “flesh” of commonality in terms of collective strivings, ways of tending to each other in precarious circumstances?

Entang Wiharso

3. Popular Economies

Popular economies could be considered as a kind of flesh, a body that has no inherent coherence or set of boundaries, something that extends and retracts, that appropriates various tools and vernaculars, the rests more in the gathering of details that in a particular logic of operation.

Popular economies refer to the variegated, promiscuous forms of organizing the production of things, their repair, distribution, use, as well as the provision of social reproduction services that simultaneous fall inside and outside the ambit of formal capitalist production. Neither reducible to notions of informality, shared or social economy, the popular embodies the various efforts undertaken by those with no, partial or unsustainable access to wage labor to not only generate a viable livelihood but to anchor such livelihood in forms of accumulation that enable them to participate in larger circuits of sociality and to elaborate the semblance a public infrastructure.

Popular economies are always mutating in terms of repositioning themselves in relationship to their availability as important domains for the extraction of value and the ongoing exertion of exploitation for more powerful institutional actors.

That which seeks to “withhold” itself from subsumption in circuits of capitalist extraction or from being relegated to the status as an economy in reserve—instruments of limited accumulation for those considered expendable—always must recalibrate expectations and practices in order to retain as much as possible the worth of its own efforts. That which is witheld might be considered “the human dimension” even as it is reliant upon various non-human actors.

4. The wasted remainders of human life

Urbanization is extended across various landscapes in part through the dispersion of calculations and automatization that displace the importance of human intention and cognition. What, then, are the “remainders” of urban systems—on the surface apparently useless, wasted or irrelevant—that hold within them vital traces or incipient formations of the human within the urban? What infrastructures, sites or domains avail themselves to the elaboration of and use by various constellations of collective life, licit and illicit?

The activities of those converted to apparently sheer labor, or relegated to labor in reserve give rise to alternate forms that Henri Lefebvre calls the residues hiding in plain sight. In the third season of Italy’s most popular television series, Gomorrah, the urban landscape is the main actor.

Here, across abandoned factories, dilapidated housing projects, freeway underpasses, ruined seaside resorts, waste dumps, empty churches, unused parking garages, and jettisoned construction sites an urban economy is pieced together and violently contested. While the proceeds of the activities of an amorphous Camorra are invested in gleaming office towers and offshore accounts, the everyday transactions that forge temporary alliances and betrayals, load and unload narcotics and other contraband, or act as venues for meetings between the licit and the illcit all take place among the unused, wasted remainders of an urban fabric that is always moving on somewhere else, seeking renewal and greater levels of abstraction.

In the wasted peripheries of Naples and Athens, a vast network of Chinese manufacturing unfolds largely in secret. The suburbs just beyond Gare du Nord are the sites of intricate home-grown real estate systems that house the barely documented, that operate as the interfaces and intersections among various diasporic commercial activities, all under the pretense of being car washes, petrol stations, box stores, delivery services, auto parts markets, and recycling centers.

Through these are the backdoors onto a larger world, of goods and services moving outside official channels, of ethnicities being sutured into provisional complicities. Here, a “strange” urban geography emerges where it is not clear what things are, what they do, or what form they take. The apparent function of things, the ghostly spectres of their past identities shimmer into a blurred network of connections, both inviting and circumventing new modalities of urban control

Entang Wiharso

Summary

If our familiar and relied upon versions of the urban human are being radically reshaped through economies of calculation, the proliferation of territories of experience and the conversion of human life into financialized entities, through what medium does such conversion take place and on what terrain will contestations about this process take place? Here, affect becomes key, both as something subject to calculation but also exceeding it.

What kind of bodies will populate the eventual urban? Here a focus on blackness as a generic term becomes important because it carries with it a long history of having inhabited urban spaces in ways that did not conform to the narratives and geographies of normative human life. Through blackness it is possible to think through a specifically urban flesh to human life.

If the margins suggest a terrain through which it might be possible to envision future forms of the human that have always already been immanent in urban settings, paying attention to the supposedly wasted remainders, useless spaces of urban life become potentially generative sites for investigation. The relationship between calculation, affect, remainders, and flesh entail an economy—a means of understanding use and value.

As popular economies are relational economies in that they are oriented toward putting things into all kinds of relations, constantly changing what any particular thing might mean, might count for, or be used for at any particular time, then they become sites to understand how the “urban human” reflects the interweaving of the human body and human cognition with other entities, bodies, and materials. Popular economies become important sites to observe the emerging practices and politics shaping these relationalities within the scope of constructing an urban existence through specific contexts of exchange, production and transaction.

0 notes

Text

Urban Human: a small treatise, part one

Edward Burtnysky

If the “human” is to be recouped as a viable entity through and around which the urban is to make sense and be sustainably developed, such a process requires grappling with four fields of investigation.

1) The implications of racialization, particularly the enduring role antiblackness plays in the organization of urban governance, 2) reworking notions concerning urban tissue into those of “urban flesh”—thinking through the very materiality of the contemporary and prospective human form; 3) working through various instantiations of popular economies—those ways of making, repairing, and transacting that exist both within and outside the logics of capital and; 4) engaging the wasted “remainders” of urban life, its apparently useless and banal spatial products that could be considered “uninhabitable.”

While human endeavor may be most easily seen as threatened by the prospects of a singularity, where human cognition is subsumed by artificial intelligence and robotics, or generalized automation, the vulnerabilities and potentials of urban humans are largely those of their own making. At the same time, these “failures” should not be construed as a fundamental deficiency of the human.

After all, the human crosses a wide range of manifestations. The urban human as a concept would suggest as much in so far as the urbanization of the human results in different versions of human life that constantly have to be sutured together. Thinking about degrees of urbanization is not a matter of how particular instances of the urban conform or deviate from some kind of overarching normative functioning, but rather how the urban “shows up” in any specific instance of observation; that it is something potentially present in any place. The conceptual challenge then is not to decide upon whether something is urban or not, but rather to dynamically account for its oscillating appearances over time. The same challenge would then also apply to thinking about the human.

At the same time, human endurance may no longer be strictly conceptualized in “human” terms; that is, such endurance may be best experienced as the relinquishing of human form in favor of new bodily and cognitive configurations, sometimes viewed as a post-human. Here, the urban human, might more productively be seen as not something yet to be invented, but as a modality of living that is always already present within the seemingly marginal, wasted and tentatively experimented spaces of the urban.

It may be found in the body’s capacity to hold that beyond its own processes of self-recognition; its own inter-woveness in quilted geographies of sense and materials that are the properties of no one, of entities that have no clear names, and collectives that have no set identities or boundaries. In other words, this may point to a human yet to come, yet already here. This is not to say that the urban human is attached to specific conditions or space, but rather to emphasize the productive use of the “margins” as a starting point to discover all of the things that human is or might be.

Accordingly, the “urban human” may act as a chiasmus, a mutual reiteration. This does not mean that the urban=human, but rather that the “urban human” constitutes an urbanization of the human that takes it away from a self-preoccupied reflexivity. It enjoins it as a composite of an interwoven fabric of material and immaterial entities, and that the urban can be animated by the particularly human strivings for freedom.

The mutating geographies of blackness, the ambiguous unfolding of popular economies along always shifting boundaries between capital and non-capital, and the capacities of the seemingly useless to act as a locus for the illicit—that which operates outside the law—provide critical points of entry into this conjunction of the “urban human.” The urban human is its own specific conjunction—neither specifically urban nor human, but both as something inextricably linked. Additionally, this “urban human” is that which is left over after all of the formatted spatial products, high-speed security trades, inter-operable data regimes, and media saturated harvesting of desire have colonized urbanization.

Stepping-stones to researching the concept urban human

There are three domains of investigation that can act as stepping-stones into explorations of the urban human that don’t presume it to be a stable entity or concept. These three domains would be the affective, calculative, and blackness. Each presumes the human as something destabilized, distributive, and contested. Each presumes that the coherence of the human is sustained by operations that at one and the same time always threaten to disrupt that coherence. Each points to the conditions through which the human is transformed and the extent to which a recognizable human form re-emerges from such transformations.

“Humanity has left the building.” This is an increasingly common invocation pointing to the widespread automatization of everyday production, the intensity of ruthless regard for the vulnerabilities of residents, and the hegemony of the axiomatic. The latter primarily refers to the unquestioned, self-evident, and perpetual continuity of capital as that operating system for human transactions.

Long having moved on from simply defining the logic of economy—the process through which things that are made enter into particular kinds of use and valuation—capital is the DNA of reproduction, a mathematics that penetrates into nearly all domains of existence, aimed at the maximization of value based on the extensive harvesting of nearly everything as a cheapened resource. In urban contexts the degree of capital’s coverage can be witnessed in the generalization of real estate from land and the built environment to the very affective dimension of human life.

This means that urbanization not only entails a political economy of land organized around human inhabitation, but also political economy of affects and experience, where humans are not only inhabitants but also marketable resources. Affects, as the pre-conscious, transindividual propensities and inclinations of human bodies to act, to feel, collaborate and decide, become materials to be harvested, codified, and transacted.

That which would seem to be one of the key defining features of the urban human is converted into an extension of the commodity form, aggregated, traded and calculated so as to maximize the powers of pre-emption deployed by corporations and states. Pre-emption refers to the capacity to shape and intervene into eventualities no matter what; to deploy eventuality—an uncertain something to come, a potential for unanticipated transformation that lacks definition—as a tool within the present. Pre-emption is a way of acting on the present that owes no allegiance to the agendas or strivings of the past; it is a modality of knowing and acting that need not respect the integrity of any specific entity, context or circumstance.

kaylan f michael

Rather, it relies upon perpetual calculation, the running of algorithms to generate multiple associations of data derived from the proliferation of parameters across the environment, and that question the nature of any entity. Uncertainty, about what things are, how they are assembled, and what they are capable of doing is brought within the present as a means of constantly hedging and leveraging the potentialities of various combinations of action to generate specific dispositions of events. In other words, as urbanization processes are organized not simply around the maximization of ground rent or spatial fixes and platforms for circulating capital, but on maximizing the productivity of uncertainty itself, the very notion of the human is altered as well.

Here, the archives of human memory, the histories of human valuation, and the forcefulness of a “human will” become increasingly insignificant markers for engendering a future. As Agnieszka Leszczynski (2016) points out, using what she calls, the”‘urban derivative,” cities are dissolved “into discrete codifications of places, denizens, flows, and events reassembled across data flows via an algorithmic calculus that speculates on the imminence of particular kinds of city-assemblages that loom on the horizon of possibility”.

This is why a focus on affect is an important complement to research on various forms of urban metrics, growth strategies, provisioning systems, and automation. For modernity, as a particular mode of reflexivity, a means of regarding ones actions simultaneously as a participant and a detached observer, is further intensified as it is coupled with the proliferation of media and technicities. For much of contemporary media supercedes human cognition in their capacity to interrelate an always expanding series of data, variables, and events considered relevant to effective human prospering.

Given the important attention to studies on urban governance and its increased emphasis on co-constitution, to what extent, then, can the predominant tropes of equality, democracy, justice and citizenship continue to do the “work” of substantiating and sustaining the concrete abstraction called, “the human”, across contemporary urban contexts? For the human—as a generalization from the specific genealogies, practices, and lifetimes of specific bodies, their thoughts and aspirations—requires a mode of enactment and regard that generates an experience, not simply a conceptualization, of the common.

What would urban humans be without the capacity to be enjoined on a level that exceeds the specificities of discrete and divergent lives, but yet incorporates these specificities as critical evidence for the fact of human existence? Might it be necessary to rethink viable planes of commonality that address the implications of both the prevailing conceptualizations and experiential histories of the human?

At the same time, the “human” also embodies a troubled political history. In many ways the privilege through which a particular mode of living has been consolidated as “human” posits the seeds of its own demise. The city existed as the locus through which certain of its inhabitants could reflect on their being as a singular prerogative untranslatable across other modalities of existence. It was the place that formed a “we” unrelated to anything but itself, Yet this “we” was inscribed as the node whose interests and aspirations were to be concretized through the expropriation and enclosure of critical metabolic relations. The “we” as a commons thus becomes partial—both in the sense of incomplete and judgmental.

For the capacity to reflect and manage the recursive intersections of materials, space, and bodies required gradation. Gradation would specify various levels of capacity and right. It would designate who was to be considered human or not as the means to capture the volume of labor sufficient to monumentalizing the human form as the living embodiment of property and freedom. The capacity of the human to operate according to the maximization of its position required a notion of free will, of the ability to act freely amongst otherwise constraining interdependencies. This freedom necessitated relegating certain bodies to the status of property, capable of circulating only through the transactional circuits of economic exchange and valuation.

Existence that is staked on the protracted and relentless constitution of blackness as the nothing that humans overcome in order to recognize themselves as free must continuously demonstrate a capacity to keep blackness in line. To a large degree the defense of the “human” has been predicated on blackness and, as such, the compensation for the demise of the human, now largely marked as its destructive actions as a geological force, is to be found in the “overcoming” of anti-blackness.

In other words, the period of the Anthropocene is to be addressed through either the vacating of this world or through a more judicious immersion in this world—an immersion now often envisioned as a journey through “blackness.” At the same time, as Achille Mbembe points out, the transformation of blacks into commodities or into “object-humans” or humans-with-prostheses – which happened in that early stage of capitalism—could now be considered potentially as a universal becoming-black-of-the- world.

Thus, the human is something broken, broken in the first instance in its self-reflexion on itself, as living out the idea of itself as sufficiently detached from the world to be its orchestrator. Ironically, being reduced to a thing that can be moved around and recombined, which is seen as the diminution of human life, may be that which holds the most opportunities for it.

At the same time, the operations of technocapitalism, with its emphasis on optimality and perfected coordination of data sets and actions, treats the human as the primary impediment to ongoing earthly survival. As Mbembe tells us, this condition demands a particular kind of observation and writing: to write is to try to repair something that has been broken, to again weave ties between entities that have been separated so that the subject might find a possibility to recreate meaning where meaninglessness prevails.

0 notes

Text

A matter of form (2)

(kaylan f. michael)

There are spare parts stores in Delhi, filled to the brim with every imaginable item that is and has been used in any type of electronic equipment for decades and piled along endless and crowded shelves. There are no formal inventories or classification systems, no records or maps indicating precisely where a specific type of item has been lodged. Rather, the staff quickly move through the aisles of circuit boards, monitors, pins, wires, bearings, battery packs, and cartridges according to a calculus that intersects, for example, the fungibility of a part, its capacity to play a role in compositions that differ from its original position, its roundness or flatness, color and texture, its relative rarity and prospects for reuse. All the staff not only has memorized such a calculus but come to intuit it as well. So here a working geography is constituted not by subjecting the details of a particular item to strict classifications of what that item was in the past, but rather what it could be and the apparent likelihood of that disposition.

In other words, there is a tenuous form at work that enables a sense of continuity, of parts being related to other parts, of a sense of parts pointing to each other as potentialities in different virtual assemblages. Yet there is no fixed “body” involved, no strict order of coherence. The array of materials is curated as a speculation, but a speculation that requires a shape, some kind of measure that might indicate how things that are occurring now might be related to things occurring “then”—as some kind of volatile and temporary amalgamation of past and future; a “then” that is not specified either way.

All of these details, these parts, have been somewhere else and carry the effects of their past belongings now shaken off partly within a dynamic mode of waiting, waiting to see what might become of them. Customers, not privy to the working maps of the staff, are equally encouraged to roam around. They may have come in with specific requests but the encouragement to roam is a lure to see if anything comes to mind, to dream their plans differently and not worry if the risks they take in selecting an item against the grain doesn’t work. The owner reassures them that the parts are always returnable, if not at the same price. Customers are encouraged to then pursue idiosyncratic purchases, purchases against the grain, which in turn add new twists and turns to the calculus underlying the store’s geography.

Here we encounter the idea of form as “a strange but nonetheless worldly process of propagation … one whose peculiar generative logic necessarily comes to permeate living things (human and nonhumans) as they harness it” (Kohn, 20). Kohn emphasizes the spontaneous, self-organizing apperception and propagation of iconic associations in ways that can dissolve some of the boundaries we usually recognize between insides and outsides.

The gathering up of details in and through form not only narrates regularity to things, but the reiteration of multiple possibilities. The stops lights adjusted to flows of traffic, the rhythms of use for the car wash that never closes or for the supermarket across the road that keeps similar hours; the schedule of garbage trucks and street cleaning machines, the amalgamations of schedules of people leaving and coming back from work; the daily rituals of storefront shutters open and closed; the punctuations of police sirens and emergency vehicles; the morning rush to get to school and the lingered exits in the mid-afternoon; the delivery trucks piling up on a single thoroughfare slowing down the circulation of traffic; the roars from a crowded bar ensconced in front of a televised sport event. All of these instances have their parts to play, have more or less detailed itineraries of execution. All are also detached from each other as observable events, yet constitute a reality to which all must at least implicitly adjust.

What these different facets of everyday activity mean to each other is not the purview of a single participant’s perspective or those of some collective whole if such were empirically attainable. Everyone can theoretically notice when something is “out of place” if even they are paying attention. But just how out of place is a matter of people’s expectations for unanticipated occurrences, their familiarity with the cast of whatever is being enacted, but above all, their sense of form, that whatever takes place emerges and then disappears from the very “connective tissue” of which they are a part. These are not symbolic connections requiring conventions of cultural meaning that generate and pattern differences. Rather form blurs the lines of distinction as each action and entity flows into the other without cause and effect, without knowing what happened first. Details here are less marks of distinction that they are conveyors of a passing through, of resonance or sympathetic charge.

Cities are replete with incongruous landscapes, things next to each—rails, dumps, nursing homes, warehouses, prefabricated logistics offices, abandoned factories, box stores, car washes, auto repair shops, slightly dilapidated pavilion housing, and the list can go on. The point is that there are large swathes of the city whose heterogeneous inscriptions are not easily amenable to categorizations and cadastrals. Oscillating land values and uses, the reconfiguration of value itself as various assurances of contingency, and the imperative to gear the built environment towards unknown eventualities often does seem to make any kind of real knowledge about these landscapes irrelevant.

Yet in their details they do hold the possibilities of a provisional base for those targeted for their race, immigration status, mental health or wayward desires. In spreads of banal housing and barely viable commercial enterprises, there are forms for stalling, encroaching, coalescing, and incremental attaining. They are contexts in which to manipulate the details of zoning, licensing, land consolidation and parceling, building auctions, liens, abatements and property tax, as well as to momentarily withdraw from scrutiny.

It is these details that enables Fikru, a 20 year old Eritrean resident of the Kato Patisia district of Athens, to slink his way across daily routines of searching for other Eritrean associates he barely knows, checking the various relief offices for food parcels, scanveging the streets for potentially useful discarded items, waiting his turn to sleep in an overcrowded hostel room he shares with ten others, and all the while trying to garner a sense of what is going on. It is a compendium of his assessments about how other refugees without papers are making it, how to stay out of the way of shakedowns and parasites and scam artists. The ebbs and flows of circulations of all kinds, the appearance or absence of various kinds of officials, authorities, bosses or enforcers, the oscillations of crowdedness and emptiness, of groups on their way somewhere, of permissible or viable trades or transactions on the street, of the sheer volume of things, be in noise, materials, bodies—all are details around which Fikru’s movements and thinking momentarily fix themselves to in order to switch somewhere else, always in the middle of things.

“While my sheer survival is not really in question, everything else is; all my training is useless here; I must unlearn everything but I also cannot come to any conclusion too fast; I have to give myself some space to think right about how all these different people might think about me; I have to insert myself into their thoughts in a way that clears the way for me.” “Most people in this neighborhood don’t come from here, and they are all doing the same thing.” We have little way to be together except for this task that essentially divides us but, here we are, and we must pass through each other in order to find what we are going to be.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

A matter of form (1)

Tim Portlock

Urbanity built on antiblackness keeps the expendable, the nothing, close as a constant reminder of what it is not, as something available to be operated on, lacerated, extinguished, penetrated. In doing so, racialized bodies are set at a remove, ineligible for the wanting and stabilities of that deemed normatively human.

But this calculus sets up a necessary inversion. For, what becomes removed is the spatializing of something that is not quite a world, territory, city, landscape or ecology—something else besides these things, yet close enough to being them to generate an incessant unease in our ability to secure any clear notion about what a world, a territory, a city might be. In other words, there is a modality of existence uninhabitable in any clear terms, yet which is lived in and lived with in ways that defy definitive judgement or assessments of viability. It is these zones zoned out of categorical policing that remain at a distance, the remainders of dispossession.

But then what becomes close, proximate is the harrowing unease that the supposed self-sufficiency of the human project, the white project, is insufficient in its own terms; that it is something that needs always to be propped up. After all, over there, beyond the pale, over the hill, on the outskirts is a life where work doesn’t seem necessary, where sex is plentiful, where games of chance prevail, where spells are cast, where a monstrous skill at making something out of nothing endures no matter how much it is beaten down.

So closeness entails both the certainty that bodies can be made nothing, kept in line, but also the uncertainty that there is something else besides this extinguishing that burns at the vey interior of a coherent, ordered life. And so distance also entails the certainty that nothing is something way over there, far removed from the operations of everyday normative life, but at the same time also another universe whose nothingness occludes economies of interweaving among things and spirits and sensibilities and infrastructures that can only be hinted at, apprehended with a vague sense of discernment.

Even under various forms of lock-down and containment, the insides of that which is removed continuously feed off of a body that remains hidden, indiscernible, even as individual trajectories are eminently predictable. Rodger, a detective from Brownsville’s 73rd precinct in Brooklyn once remarked in reference to trying to manage policing in the Howard, Van Dyk, and Tilden Housing Projects, “ we can count the bodies, we have a pretty good idea who belongs to what gang, we have a pretty good sense about where money is coming from, but we haven’t got a clue about the world to which any of this belongs; even as thousands come in and out of prisons and juvie, in and out of jobs; even as social workers and community workers and teachers and preachers try to keep a finger on the pulse of disputes and networks of care, it’s a life where things happen in a flash, according to their own rules, like things are connected to each other in a way that just can’t be figured out ever.”

There are, of course, attempts to close the gaps between the diffracted sense of two forms of proximities and two forms of distance. This takes place through the pervasiveness of a culture of valuation and the indeterminacy that is at the heart of it. Here, attempts to restore the clear hierarchical sense of things, their “proper order” of distance and proximity, of what lives have to do with each other occurs through the extending of value production to the entirety of life experience. So, all life becomes financialized at its very core—flesh, genetics, language, affect, and neurophysiology.

Cities do not so much hold an army of labor in reserve, but use the reserves themselves, their lifetimes, all of their makeshift, oscillating mix of calculated and desperate, intuitive and impulsive maneuvers to tend to themselves and others as raw materials from which to derive speculative domains of value extraction. Not only, as Neferti X.M Tadiar points out, are the lifetimes of the poor harvested for economies based on internment, recycling and rehabilitation, but whatever livelihoods are eked out in the interstices of conventional labor, production and circulation is put to work in the elaboration of new commodity circuits Maintaining coherence in the operations of institutions of all kinds, given the volatilities inherent in the larger settings in which they are situated, requires adjustments of all kinds. Such adjustments entail the possibility of cheap and temporary labor, payoffs, circumvention of rules, the proliferation of all kinds of dirty and off-the-book jobs whose performances remain largely unregistered in conventional imaginations.

For those relegated to the status of nothing, excluded from normative human attainments, an entire economy is generated from leveraging what it is that such (non)humans can do. Unsettling the reserves, disrupting stabilities resets the value of existing social relations. Residents have to scurry around for new exposures and connections, as limited resources are shifted around. People are willing to do things they were unwilling to do in the past; new dependencies are created; bodies are taken in and out of circulation, as a favor to someone who then come to owe someone else, perhaps his or her life.

So accustomed to viewing life at the urban edge as either the purview of individual moral success or failure or in terms of an overarching structural condition, we often fail to see the extent to which lives, laboring or not, are the raw materials from which reputations can be marketized, through which symbolic capital can be garnered, and objects diverted from the customary protocols and circuits of exchange. The hierarchies of what is accessible or not are thus disrupted.

In cities where many livelihoods have been predicated on the capacity of individuals to become many different things for many different people, lifetimes, as Tadiar explains, become increasingly derivative and are lived as if financial derivatives. Urban renewal and development have always speculated on the extent to which certain bodies could be removed, enrolled, and deployed at affordable prices.

And so some parts of the city are converted into a slow-burning game of everyone extorting everyone else; others are treated like start-ups, continuing long histories of incremental experimentation with complementary forms of entrepreneurship; others are bastions of apparent illegality that put food on the table through a host of illicit practices that generate substantive income for police and politicians; still others exude a sense of self-sufficiency inherent in residents maintaining a wide range of low-paying jobs somewhere, who diligently keep internal disruptions to a minimum, yet can easily be picked off and relocated if necessary. In many poor and working class districts things are constantly being rearranged, as different constellations of residents, internal and external brokers speculate on new construction for cheap rentals or clear away areas for land to be banked.

All of these practices of what we might have called autconstruction can now constitute the underlying asset for forms of managing uncertain futures that will never belong to the residents themselves—from pay as you go services, to fees for recycled materials, to the conversion of a barrio into cheap sex motels, to gentrification, to enforcing household expenditures through conditional cash transfers, to leveraging the killing of drug addicts in order to make new connections with local political bosses.