A blog about the War of Spanish Succession (1701-1715) and related events

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

1712 Jean-Baptiste van Loo - Louise Hippolyte Grimaldi with a view overlooking Monaco

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

My mutuals are excellent in building extensive and elaborate siegeworks, your mutuals struggle to dig a knee-deep moat.

3K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Recreation of the miquelets,

Source: Miquelets de Catalunya

1 note

·

View note

Photo

1710-1715 Unknown artist - Charlotte Christine of Brunswick-Lüneburg

93 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Royal Vaisseau, a late 17th century ship of line, puking fire by all the cannons. Pbom !!, by Edouard Groult 2022

357 notes

·

View notes

Text

These Silk fan depicts the siege of Gibraltar in 1779- 1783. Known as the Great Siege, it was an unsuccessful attempt by Spain and France from 1779 to 1783 to capture Gibraltar from the British.

The siege of Gibraltar with Spanish ships and troops in the foreground, the verso with engraved key in Spanish decorated with weapons of war on either side, mounted on ivory sticks, the sticks decorated in silver and gilt with a fort, ship and flag, the guardsticks carved and pierced and with silver and gilt depicting a ship and drums, 27.5cm

237 notes

·

View notes

Photo

One of the rules that the Spanish king created when Castile (Spain) invaded Catalonia in the year 1714 was this: Catalans were limited to one knife per family, which was to be used only to cut bread and had to be chained to the table.

If you visit old Catalan houses nowadays, you may sometimes still see the chain that tied the knife.

Other changes in Catalonia imposed by the Spanish military occupation included the following:

All the Catalan institutions were abolished and they imposed the Spanish absolute monarchy with Spanish governors chosen by the king

Imposition of the Spanish language as the only official one, banning the use of Catalan in public documents

Jail or execution of people who had had an important role in the defense of Catalonia during the war. There were also some extreme cases, such as general Josep Moragues. He was dragged alive through the streets of Barcelona, killed and his body mutilated. His head was exposed for 12 years on top of the entrance gate to Barcelona as a warning to anyone who thought to rebel

Jailing of thousands of Catalan people

All the possessions of people who were known to have fought in defense of Catalonia’s independence (including the ones who had died in the war) were confiscated

Catalans were forced to house the Spanish army in their homes, and every town had to dedicate a percentage of their fields to grow food for the horses of the Spanish army

Catalonia had to pay very high taxes to Spain, and those who refused to pay it had the army sent to their home to force them to pay

Everyone who had worked for the Catalan administration or governments was fired, and those judges, lawyers, scribes, nobles and members of the church who had been against the Spanish invasion were forced to go on exile

Destruction of many castles all around Catalonia

Destruction of historical documents like the Annals of Catalonia by Feliu de la Penya and all the documents printed during the war

Abolition of Catalan money and prohibition of Catalonia to ever make its own money again, and the coins already in circulation would be worth one third of their original cost

Prohibition for Catalan people to have weapons. Prohibition of the Catalans who had had the right to have a sword (it was an honour to be awarded the right to carry sword) from using it.

Replacing the Catalan symbols (like the senyera and Saint George) for portraits of the Spanish king Felipe V, the Bourbonic coat of arms and other symbols of the Spanish monarchy

Destroying one third of Barcelona, the houses of hundreds of families who had nowhere to go, to build the biggest citadel in Europe in order to control Barcelona

Every day at 2 pm the Cathedral of Barcelona had to ring the bells for a prayer to the Spanish King, to reminds the citizens of the occupation. The bell called Honorata was destroyed for the crime of having rang to call citizens to defend the city against the invasion

[The photo is from Casa Gassia, an old house turned into museum in Esterri d’Àneu (High Pyrenees, Catalonia). Photo by Jordi Borràs for La Mira.]

363 notes

·

View notes

Photo

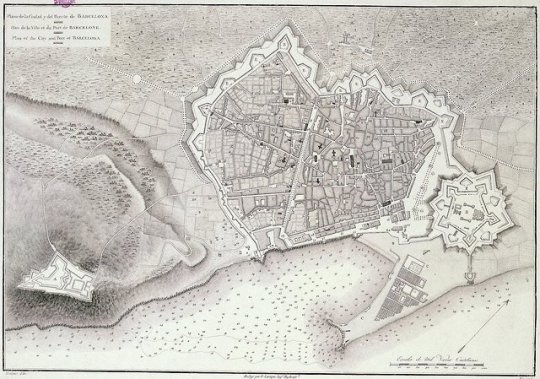

The Citadel of Barcelona was the biggest citadel in Europe at the moment of its construction, as well as the only citadel built with the purpose of attacking and controlling the city instead of defending it.

Its construction started in the year 1715, right after Castile (Spain) invaded Catalonia as part of the War of the Spanish Succession, during which Castile had also invaded the other Catalan-speaking countries the Kingdom of València and the Balearic Islands.

Barcelona, as the capital city of Catalonia and the last strategically important city to resist the Spanish invasion thanks to the population’s organization, and being a city who often revolted against injustice and famous in all Europe for its revolutionary attitude, it was seen as a dangerous. According to the Spanish government, the objective of building it was to «dominar al pueblo de Barcelona» (“to dominate the people of Barcelona”). To control the citizens and stop a possible uprising against the Spanish oppression and rule, a plan was created to build the enormous citadel, a fortification in the Montjuïc mountain, and many military caserns for the Spanish army as well as re-converting older buildings such as the University and different convents into military quarters.

To make space to build the citadell, a whole neighbourhood was destroyed: the La Ribera quarter. 1,016 homes were destroyed and, for further humiliation, each family who lived in that quarter was forced to destroy their home with their own hands.

The city hall of Barcelona requested to take down the citadel in 1794, 1840, 1845, and 1862. All of them were denied. The citadel was finally taken down in 1869, after the Revolution of 1868. Nowadays, the space is a public park. Under it, there are still remains of the basements of the destroyed homes.

67 notes

·

View notes

Photo

1717 Nicolas de Largilliere - Portrait of Voltaire aged 23

162 notes

·

View notes

Photo

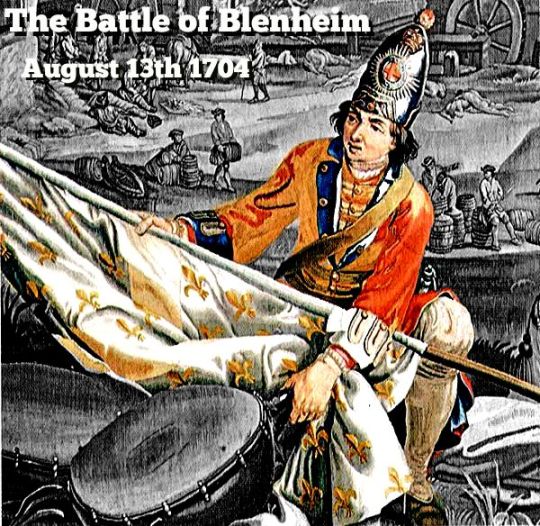

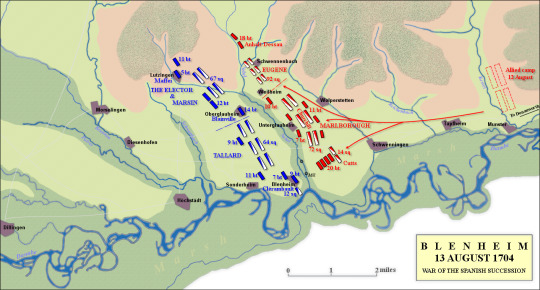

Battle of Blenheim, August 13th 1704.

On this day, one of the most important battles in British history took place. Although not quite as well known as it deserves to be, it was crucial for preventing France under Louis XIV, the notorious ‘Sun King’ from becoming as powerful as Napoleon was at the height of his power. It also cemented the reputation of John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, ancestor of Sir Winston Churchill, a figure who would himself play a decisive role in a future British war against a different continental enemy.

The War of Spanish Succession

The War of Spanish Succession had been precipitated by the death of Charles II of Spain, last of the Spanish Habspurgs in 1700, who had bequeathed the throne to Philip, Duke of Anjou, who belonged to a cadet branch of the French Bourbon dynasty. However, the throne was also claimed by Archduke Charles of the Holy Roman Empire, son of Leopald I, Louis XIV’s long standing enemy. Louis XIV’s enemies viewed a Bourbon on the throne of Spain, with it’s vast Empire, as unacceptable, in the same way Louis XIV viewed being encircled by rivals and enemies as similarly unacceptable. England (later part of Great Britain) entered the war in 1702 alongside its Dutch and other allies in order to prevent a nightmare scenario whereby Louis XIV, a lifelong enemy of England and Holland, would get to preside over a continental superpower consisting of the most populous nation in Europe and its largest and wealthiest Empire.

Marlborough’s March South

At the beginning of 1704, the war was not going very well for the allies. The French were pushing the Austrians back across Italy into their heartlands, at the same time Leopold I, the Holy Roman Emperor was facing a rebellion in Hungary, and Bavaria, a technical vassal of Leopold I, had declared in favour of France in order to protect their governorship on behalf of Spain in the Spanish Netherlands. John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough, in command of Anglo-Dutch forces in the Netherlands, wanted to march south along the Rhine in order to confront the threat to Vienna, which if it had been captured, could knock Austria out of the war and thwart the balance of power England sought on the continent for its own security. The Dutch however, where cautious, and refused him permission to take his troops away from the Dutch frontier where they feared an invasion by French forces.

Marlborough plotted in secret to take English forces and march south anyway, whilst deceiving both his Dutch allies and the French of his intentions, who initially believed he was planning to attack French forces in the West. However, he turned South and East along the Rhine, presenting the Dutch with a fait accompli. They could either march with Marlborough, or run the risk of his army being defeated without Dutch help and therefore leave them isolated and unable to resist a French invasion.

And so on May 19th, Marlborough set out to follow the Rhine with 21,000 men (including 16,000 British troops), to be joined along the way by allies from Denmark, Prussia, Hanover, Saxony, Austria and Hesse. The journey was fairly rapid, despite the poor roads and often poor weather, as Marlborough had taken care to plan ahead and set up supply depots along the way in order to speed the advance up and avoid alienating the local populace by looting them for supplies, as the French typically did. As Marlborough intended, the march south also drew French troops away from the Dutch frontier, much to the relief of the Dutch Government.

Marlborough was later joined by Prince Eugene of Savoy, a Frenchman by birth who had once sought employment in the French Army, only to be rebuffed, and so had entered Austrian service instead. In the meantime, Tallard, Marshall of France, was marching east through the Black Forest in order to link up with Bavarian forces and defend against Marlborough and Eugene.

The Armies Deploy

The two armies eventually met near the village of Blenheim (also known as Blindheim) on the 12th of August, and the two allied commanders resolved to attack Tallard’s forces the following morning.

Tallard had placed his army on high ground in front of a marshy stream called the Nebel, which allied forces would have to cross in order to confront Franco-Bavarian troops on the ridge ahead,. In addition, Tallard was able to anchor his right flank by garrisoning a substantial force within the Village of Blenheim next to the River Danube, whilst his left flank was partially protected by heavy woodland and the village of Lutzingen, along with another settlement called Oberglau just to the left of Tallard’s centre, which was also garrisoned and barricaded. Tallard also slightly outnumbered the allies, with 60,000 men compared to 56,000 on the allied side, as well as 90 artillery pieces to the allies 66.

Conventional wisdom would have suggested that an allied attack under such circumstances would be madness, but Marlborough and Prince Eugene decided that such conventional wisdom, if adhered to by Tallard, would inspire complacency in the French and their Bavarian allies, as the last thing the enemy would be expecting was an attack uphill against their superior numbers and fire-power.

The Battle Begins

At 7 AM the following morning, the French observed the allied army approaching to attack, and organised their units into position. At 11 AM, the battle commenced when the French batteries opened fire on the allied lines. Fortunately, many of the troops were partially obscured by unharvested crops growing in the fields, which made it much harder for French gunners to direct their fire towards them. Marlborough ordered his men to lie down in order to protect them from the full effects of the bombardment, and was himself almost killed when a French cannonball ricocheted off the ground underneath his horse. Marlborough waited until Prince Eugene’s forces where in position before he would commence the attack.

As both sides exchanged artillery fire, Prince Eugene was busy deploying his forces to the allied right. At 12:30 a message arrived from the Prince informing Marlborough that his forces where finally in position and that the allied assault could begin. Rowe’s Brigade commanded by Scotsman Archibald Rowe attacked the French right barricaded in Blenheim, with Rowe himself fearlessly leading the charge from the front. He ordered his men to hold fire until he could strike the walls of the village with his sword. Rowe managed to survive long enough to reach the wall and smack his sword against it, but fell mortally wounded soon after, as did two of his aides who dashed forward to try and rescue him. The British opened fire with their muskets, but the attack was repulsed and they were forced back. A French counter attack was however in turn repelled by steady volleys of British platoon fire that drove the French back behind the walls and barricades of Blenheim. An attack by Tallard’s cavalry attempting to role up the British infantry was also repulsed. After a period of reorganisation and rallying, the British left, under the command of Major-General Lord Cutts renewed the assault on Blenheim, but they were forced back once again. However, the attack did panic the commander of the French right, Marquis de Clerambault into moving no less than 27 French battalions or 12,000 men into the village to ensure that it was held, packing them in so tightly that they made easy targets for allied guns and muskets, whilst they in turn could not bring their own muskets fully to bear against the redcoats. It also meant they could no longer support nearby French cavalry effectively.

The two failed assaults had caused heavy casualties however, and Marlborough ordered Cutts to cease his attacks and hold his position in order to keep the French penned up in Blenheim whilst he advanced his centre forces across the Nebel and the marshy ground to assault the French centre as Eugene attacked from the right and kept the Franco-Bavarians occupied there.

Attack on the Centre

Tallard allowed British forces to cross the Nebel relatively unmolested except for some artillery harassment. He hoped that by allowing them to cross the stream and over the marshy ground that they would be trapped and unable to escape quickly across the marshland, allowing him to smash the allied centre with a devastating counter-attack.

Despite a concerted attempt by the French cavalry and supporting infantry to attack Marlborough’s infantry in the centre and open up a flank on the right of the British left, the attack failed and the French cavalry was repulsed by a counter attack from British cavalry, though they themselves were compelled to fall back temporarily in the face of heavy French musketry when they advanced too far in pursuit.

Prince Eugene’s Assault

Prince Eugene’s initial attack on the French left near Lutzingen met with limited success. Although the Dutch, Danes and German forces under his command managed to drive the Franco-Bavarians back , even to the point of reaching the enemy’s cannons and engaging in hand to hand combat with French artillerists, they were driven off by a counter-attack from the enemy’s infantry. The enemy gunners swiftly brought their cannon back into action, deploying them as giant shotguns unleashing a storm of canister that shredded its way through Prince Eugene’s retreating forces, causing horrific casualties. Despite the failure of Prince Eugene to make a breakthrough, his attack did serve to tie up much of Tallard’s left flank and distract them from Marlborough’s main attack through the centre.

The Collapse of the Franco-Bavarian Army

In the centre, a renewed allied assault finally broke the French cavalry, who, overcome with panic, began to flee the battlefield across the plain and over the Danube River to the South, where many of them drowned. As the French cavalry ran, 9 battalions of French infantry, now unsupported by cavalry and therefore trapped, were bombarded without mercy by Colonel Blood’s (son of the notorious Tower jewel thief) artillery, until they themselves broke and ran, only to be pursued and cut down by English and allied cavalry. During this rout, Marshal Tallard himself was captured, as Eugene’s forces on the allied right and Marlborough’s forces on the left advanced on the villages of Luzingen and Blenheim respectively.

Faced with an irresistible onslaught backed up with artillery, the Franco-Bavarians set fire to Lutzingen and Obergrau to cover their retreat before withdrawing. As Eugene advanced, the English began to envelop Blenheim, which was still holding out even as the rest of Tallard’s forces were being driven from the field.

Assault on Blenheim and French Surrender

Although Blenheim was still heavily garrisoned with French troops, they held on with dogged determination, forcing the British to fight a vicious and brutal close quarters struggle with bayonet, bullet, butt and fist from house to house and street to street. Eventually, they managed to drive the French into a walled Churchyard and its surrounding buildings. At this point, much of the village was in flames, partly through the constant gunfire, but also through deliberate arson on both sides as they tried to flush the enemy out with fire or obscure their manoeuvres. Many troops on both sides, particularly the wounded, suffered a grisly fate, consumed by the flames where they lay helpless and unable to escape.

By this point, Clerambault was missing, presumed dead and what was left of the French garrison was commanded by the Marquis de Blanzac. During a brief truce agreed between both sides in order to recover their dead and wounded, the French learned that their commander in chief had been captured and the rest of their army had fled from the field. As night fell, Blanzac, persuaded of the hopelessness of his position, agreed to surrender the remaining 10,000 troops under his command. The battle was over.

Aftermath

The allied victory was decisive, but had come at a heavy cost. 14,000 allied troops had been killed or wounded, but the French and Bavarian forces had for their part lost 20,000 dead or wounded with a further 14,000 taken prisoner. What was left of the enemy army limped back to Strasbourg, haemorrhaging several thousand more troops through desertion along the way.

French plans to take Vienna were in ruins, as was the nigh on invincible reputation of Louis XIV’s forces. News of the stupendous victory reached England on the 21st of August, amidst much rejoicing from Queen Anne, Parliament and the people. A grateful nation granted the triumphant Duke money and land with which to build a sumptuous palace, known as Blenheim Palace, after the battle that proved to be the Duke’s greatest triumph. Although the war was far from over, it had put the French on the back foot and the Sun King’s hopes for a peace in his favour were dashed. It would take many more years and many more battles before the war ended in the allies favour with the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, followed by the Treaty of Rastatt between Louis XIV and Leopold I the following year. Although perhaps not as decisive in its own right as other more well known battles such as Waterloo and Agincourt, Marlborough and Prince Eugene’s victory at Blenheim had arguably saved the allies from defeat by preventing the French from knocking the holy Roman Empire out of the war and forcing an unfavourable peace on the allies that would have left the Sun King stronger than ever. It might be said that although this battle was not decisive in the sense of destroying the enemy, if this battle had been lost, or not fought at all, Britain would not have been able to achieve its later successes. For this reason, Blenheim must surely rank amongst British history’s most notable battles.

153 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The portrait of Philip V, king of Spain, hangs upside down in the city of Xàtiva (Valencian Country). Philip V was the king who militarily invaded the Valencian Country, Catalonia, Aragon, and the Balearic Islands, illegallized our language and our institutions and imposed Castilian rule.

Xàtiva hasn’t forgotten how Philip V ordered to burn down the city as a punishment for their resistance to invasion. The king’s orders were: “[…] for the stubborn rebelliousness to the point of desperation with which the inhabitants of the city of Xàtiva have resisted my arms […] my justice is decided to ruin it in order to extinguish its memory, as it has been done to punish their obstination, and to teach the lesson of anyone who might try their same mistake”. After burning the city down, he ordered to throw salt on the fields (which makes it impossible for the fields to grow anything) and changed the name Xàtiva for “Colonia Nueva de San Phelipe” (New Colony of Saint Philip).

The portrait of the man who condemned the city to poverty and oppression will remain upside down, and it has become a symbol of Valencian resistance and against the monarchy.

248 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sant Ferran Castle (Castell de Sant Ferran), Empordà, Catalonia.

This fortress, even though it’s not very well-known to most people, is the largest monument in Catalonia, and not only that, but it is considered to be Europe’s largest bastion fortress, with an area of 320,000 m2 within a perimeter of 3120 m, and cisterns located under the courtyard are able to hold up to 40 million liters of water. At its height, the castle could support 6,000 troops.

It was built in the 18th century, when the Fort of Bellaguàrdia (Northern Catalonia) passed into the hands of the French state as a result of the Treaty of the Pyrinees (1659).

On the 1st of February of 1939, the last meeting of the government of the Spanish Republic was held in this castle before the victory of the fascists at the end of the Civil War.

In the castle’s official website you can take a virtual visit that explains each part of the fortress and its history and strategical use.

36 notes

·

View notes

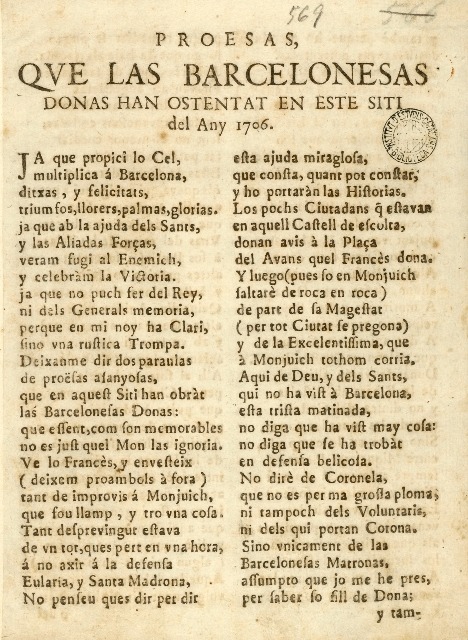

Photo

“Allow me to say two words about the unflagging feats, that in this Siege have done, the Barcelonian Women: for being as memorable as they are it’s not fair that the World ignores them.”

(“Deixanme dir dos paraulas de proësas afanoses, que en aquest Siti han obràt las Barcelonesas Donas: que essent, com son memorables no es just quel Mon las ignoria.”)

This pamphlet explains in verse what happened on May 12th, 1706. It was during the War of Spanish Succession (1701-1715), the Bourbonic troops of France and Castille had sieged Barcelona, but on May 12th 1706 the inhabitants of Barcelona got out of the city to fight the French army. All the contemporary sources agree that women had the most important role in this fight: fighting with their firearms and also aiding the wounded. The Catalans forced the French troops to leave their city and chased them far away.

That day, there was a total solar eclipse. It was interpreted as the fall of the Bourbons, since Louis XIV of France called himself “the Sun King”, and other pamphlets talk about how Charles III (the Habsburg that Catalonia backed against the Bourbons) had eclipsed Louis XIV.

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

Me, a person from catalonia, when I see a post with the number 1714

76 notes

·

View notes

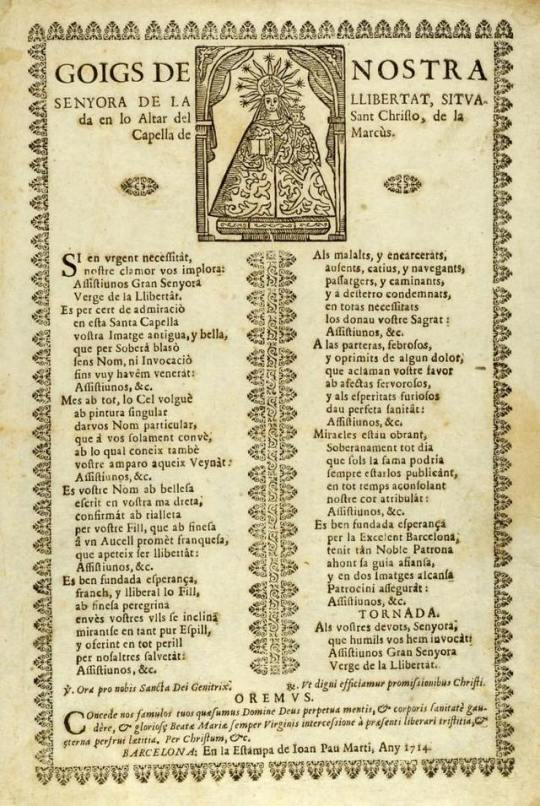

Photo

A song dedicated to Our Lady of Freedom.

Printed in Barcelona (Catalonia), year 1714, in the Catalan language.

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

ab. 1716-1720 David Richter the Elder - Emperor Charles VI and Elisabeth Christine von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel

22 notes

·

View notes