Text

Critical Factors of Emergency Department Overcrowding

As an EMT, I wish I could say my job lived up to the expectations people attach to it: fast-paced, life-saving, screeching-sirens, television-esque first responder work. Sometimes it does and I end each call with a rush of adrenaline and a feeling of accomplishment, then clock out feeling satisfied that I did something.

More and more, though, my job description seems to entail a lot of waiting. Last month, I stood against the ER wall with a patient, waiting for a bed, for five hours. I’ve done this several times. But, I'm lucky; I've had coworkers wait in the ER for fourteen hours.

This doesn’t feel like emergency medicine; like adrenaline and accomplishment. This feels disappointing and dangerous.

These long wait times are due to overcrowding, where patient influx exceeds what an emergency department can handle. Dr. Daniel Fatovich, research director and professor of emergency medicine, calls overcrowding the greatest obstacle facing emergency departments today. Current scholars in emergency medicine agree.

Overcrowding has huge negative effects on patients. Long wait times, delayed pain relief, and poor outcomes are just a few, according to Dr. Robert Derlet, UC Davis doctor of emergency medicine. Some emergency departments (EDs) have resorted to closing their doors during high-volume periods. This causes overflow into other facilities, making the issue worse. Illustrated below is one of these most prominent and dangerous effects: prolonged wait times.

Figure 1: Median length of stay in ED before hospital admission.

Reese, Phillip. (2019). From “As ER Wait Times Grow, More Patients Leave Against Medical Advice.”

Overcrowding is not a new phenomenon, having influenced emergency care for years. The late 90s saw the beginning of strong research efforts into overcrowding. Scholarly interest remains high, since the effects of overcrowding affect everyone in healthcare, from patient to provider to administrator. But even with the last thirty years of research, we’re still seeing epidemic levels of ED crowding. Derlet’s worrying observations, if not fourteen-hour wait times, should tell us a solution is long overdue.

When I stood against the wall for five hours, I naturally began to wonder. Anything motionless in healthcare is very unusual, especially in a fast-paced field like emergency medicine. I wondered what was causing this; and I wondered what was changing in overcrowding, since I’d heard of long wait times in EDs for years.

Looking at the literature reveals something interesting: there’s actually been little change in the causes of overcrowding over time. Comparing old and new literature shows that today’s epidemic blooms from the same roots as thirty years ago. These factors, identified time and time again, must be foundational to overcrowding. This is an important observation; by analyzing this lack of change, we can create better solutions to our current crisis.

---

SHORTHANDED, OVERLOADED

Across time, studies describe staff shortages as a leading cause of overcrowding. Staff shortage, as defined by Schull et. al, includes an absolute lack of employees as well as increased workload per staff member. These same authors call staff availability the single most important factor of overcrowding. Old and new research describes staff shortage in similar ways, splitting it into two components: increased employee workload and raw numbers of staff.

High staff workload stems from intense patient visits. In 1999, Lambe et. al’s data showed that “critical visits to EDs increased by 59% from 1990 to 1999 and that urgent visits increased by 36%.” (p. 430) They write that higher amounts of critical visits play into overcrowding. These higher-acuity visits increase staff workload, exacerbate short-handedness, and slow patient flow.

In 2017, di Somma et. al made an eerily similar finding. Complex and labor-intensive patient care, they say, increases the burden on nursing staff and extends wait times. They specifically mention resource imbalances: low staff availability and high patient-provider ratios. This is a direct echo of Lambe et. al eighteen years prior.

This sparks a vicious cycle of mass burnouts. Providers that drop out from stress increase the workload of others, leading to even more staff fatigue. As staff reach capacity, they simply can’t attend to new patients. These factors -- burnout, high workload, and slow patient processing -- come together to cause overcrowding. This pattern happens at all professional levels of healthcare, from my fellow EMTs to nurses and doctors.

Lambe et. al’s study also found that California lost an eighth of its EDs, or 12.3%, from 1990 to 1999. These EDs closed because they couldn’t amass the resources, namely human capital, to care for patients. This 1999 trend is repeating itself in 2021. EDs are forced to close their doors -- temporarily or permanently -- as shorthanded staff fight against waves of critical patients. di Somma et. al comment that, during their study, several EDs closed due to staff shortage. The authors sound distinctly unsurprised. They cite Hsia et. al’s 2015 study, which finds that recruiting and maintaining staff is a major factor in ED closures. In all studies, the closure of one ED redirects patients to others, directly causing overcrowding.

---

COMPLEX CONDITIONS

Staff shortages go hand-in-hand with high patient complexity to cause overcrowding. A “complex patient” is anyone who requires a high level of care. Schull et. al write that patient complexity is critical to overcrowding. They find that a patient’s complexity increases with age, length of stay, and overall health. The authors bluntly state: “...older and sicker patients contribute to overcrowding by virtue of higher acuity and admission rates.” (p. 81) Like staff shortages, this factor shows very little change over time. Studies separated by decades all indicate patient complexity as a cause of overcrowding.

As America’s population ages, patients become more complex, with fragile conditions and longer recovery periods. The poor health of many Americans complicates ED visits, too. For example, diabetes is notorious for complications like poor postoperative outcomes, kidney failure, and heart disease. Almost one in ten Americans have diabetes, according to the American Diabetes Association. With just diabetes, we can easily see how common complex patients are.

Overlapping conditions in unhealthy Americans is common and leads to longer ED stays. From slow-healing wounds in diabetes to the frailty of heart or kidney failure patients, complex patients go to the ED more often and require more care.

When I take a patient to or from the hospital, they usually have established records from frequent visits. Nurses, if I ask for a medical history, rarely waste words. They just point to the laundry list on their computer and let me skim.

Past research noted these trends of increasing age and illness. From twenty years ago, Schull et. al’s study noted these high-complexity patients in overcrowding. Derlet, in 2002, predicted that EDs will see higher numbers of patients with many complex medical problems. He wrote that these high-acuity patients would contribute to overcrowding.

Current studies and trends confirm Derlet’s predictions. di Somma et. al found that complex patients, together with overwhelmed staff, strain ED resources. The 2021 Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) report also finds a link between overcrowding and complex patients. The report states that resource-intensive patients -- specifically the elderly and chronically ill -- slow patient flow. These modern studies find the same causative factors in overcrowding as others did in 2002.

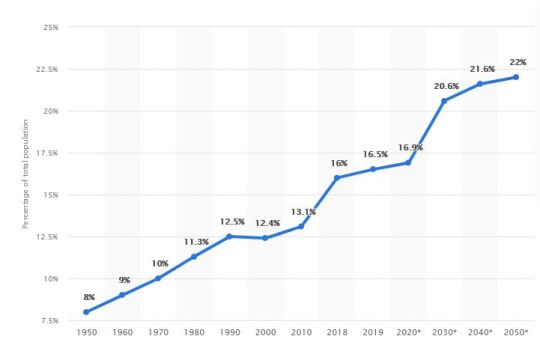

This trend of high complexity will only get worse. Again using diabetes as an example, the ADA writes that 1.5 million Americans are diagnosed with diabetes every year. Since Schull et. al’s and Derlet’s articles, an additional 28.5 million diabetics have been diagnosed. America’s population is aging rapidly, too, as illustrated in the graph below. Modern trends in overcrowding mirror these increases in age and illness. Whether twenty years ago or now, research shows that patient complexity is foundational in ED overcrowding.

Figure 2: US seniors (> 65 years old) as share of population. Statista. (2017). From https://www.statista.com/statistics/457822/share-of-old-age-population-in-the-total-us-population

---

BED AVAILABILITY

Both staff shortages and patient complexity overlap with bed availability in overcrowding, or the ability for a patient to be seen at all. Past and present literature point to bed availability as a major factor of overcrowding.

Almost every source in past literature places special emphasis on bed availability. Derlet states that filled inpatient beds are a leading cause of ED congestion. Fatovich concurs, finding that American medical beds decreased by 18% from 1994 to 1999.

This factor remains unchanged. The 2021 ASPE report finds that bed availability, proportional to America’s population size, continues to fall at a rate similar to Fatovich’s 1999 finding. The report states, point-blank, that “there are not always sufficient beds” for patient care (p. 5).

The only real change from 1999 is how EDs developed techniques to cope with limited beds. Kim et. al’s 2020 study describes these tactics, including speeding up decision times, rejecting ambulances, and transferring patients to faraway hospitals.

This is deeply worrying. Is the main factor in patient outcomes not quality of care, but if they can be seen at all?

Increases in population with no increase in bed capacity leads to overcrowding. This factor appears in both old and new literature, and its obvious importance means it must be included in a solution. For example, one hospital saw marked decreases in overcrowding after opening more bed spaces, as shared by Fatovich. We may see similar successes by treating this common cause of overcrowding.

---

WHAT DOES THIS ALL MEAN?

The last three decades of scientific study point to the same root causes of overcrowding: staff shortages, patient complexity, and available bed spaces. As these roots persist, overcrowding, too, remains a fixture of American EDs, growing to epidemic proportions.

I was drawn to healthcare by its constant evolution: its innovations, its value of research, its providers who value new information and constantly seek improvement. Overcrowding being so stagnant captured my attention.

Functional emergency rooms are invaluable. To preserve these vital safety nets, we desperately need a solution to overcrowding. Fortunately, literature shows that such foundational causes have remained consistent over time. Creating strong solutions will be much easier, knowing these key foundations of overcrowding.

I joined EMS to do something. I don’t want to be a hero or warrior or what-have-you, but EMS holds a unique, powerful position as the first point of care for emergency patients. There is so much more I can be doing than standing against the wall in an ED. Despite epidemic levels of overcrowding, though, I remain hopeful. The causes of overcrowding are well-characterized over the past decades of research. We know where to start; we only need to implement a solution. (1795 words)

---

BIBLIOGRAPHY

American Diabetes Association. (2015). Statistics About Diabetes. Diabetes.org. https://www.diabetes.org/resources/statistics/statistics-about-diabetes

Derlet, R. W. (2002). Overcrowding in emergency departments: Increased demand and decreased capacity. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 39(4), 430–432. https://doi.org/10.1067/mem.2002.122707

Fatovich, D. (2002). Recent developments: Emergency medicine. British Medical Journal, 324(7343), 958-962. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25228071

Hsia, R. Y., Kellermann, A. L., & Shen, Y.-C. (2015). Factors Associated With Closures of Emergency Departments in the United States. JAMA, 305(19). https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.620

Kim, J., Bae, H.-J., Sohn, C. H., Cho, S.-E., Hwang, J., Kim, W. Y., Kim, N., & Seo, D.-W. (2020). Maximum emergency department overcrowding is correlated with occurrence of unexpected cardiac arrest. Critical Care, 24(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-03019-w

Lambe, S., Washington, D. L., Fink, A., Herbst, K., Liu, H., Fosse, J. S., & Asch, S. M. (2002). Trends in the use and capacity of California’s emergency departments, 1990-1999. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 39(4), 389–396. https://doi.org/10.1067/mem.2002.122433

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2021). Trends in the utilization of emergency department services, 2009-2018. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/migrated_legacy_files//199046/ED-report-to-Congress.pdf

Reese P. As ER Wait Times Grow, More Patients Leave Against Medical Advice. Kaiser Health News. Published May 17, 2019. https://khn.org/news/as-er-wait-times-grow-more-patients-leave-against-medical-advice/

Schull, M. J., Slaughter, P. M., & Redelmeier, D. A. (2002). Urban emergency department overcrowding: defining the problem and eliminating misconceptions. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine, 4(02), 76–83. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1481803500006163

di Somma, S., Paladino, L., Vaughan, L., Lalle, I., Magrini, L., & Magnanti, M. (2017). Overcrowding in emergency department: an international issue. Internal and Emergency Medicine, 10(2), 171–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-014-1154-8

U.S. - seniors as a percentage of the population 2050 | Statista. (2017). Statista; Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/457822/share-of-old-age-population-in-the-total-us-population/

0 notes