Text

ReproducingーThe Great Wave

I this time done reproducing, " The Great Wave', from a image data of the original print, which I borrowed from Hagi Uragami Museum. The link:

When I first would write this article about the reproducing to introduce, I couldn't think of almost anything in particular to write since its concept and process of printmaking was basically same as the previous my reproducing of Hiroshige's One Hundred Famous View. So, I first thought I would introduce just by the photos of my printmaking scene. (Also, since I think explaining about Hokusai and the design itself has been done in many times in various media by various people, so I felt there was nothing for myself to write particularly about such those . )

However, I then came up with explaining in more detail about the concept of my previous and this time reproducing. Because there seemed little information such like that in general.

In addition, I had a sense of problem against that verifying and organizing concepts don't seem to be done properly in a project of the traditional ukiyoe reproducing. The root cause of why various contradictions, cheatings or deceptions arise in ukiyoe reproducing projects seemed to me that the concepts were not organized among the people involved, rather than issues of shortages of the materials and the skills of carver and printer nowadays.

A typical example of that is "confusing making an improved beautiful ukiyoe print by the higher skill of the traditional woodblock printmaking, with using modern improved washi and pigments than the original print, and reproducing ukiyoe print accurately as same as it was in the Edo period". Or, an example as "confusing ukiyo-e created during the Edo period and ukiyo-e reproduced during the Taisho or Showa periods." Those are examples seen among the experts. The reason why such logical fallacy occurred from the first , despite the involvement of the first class museums, researchers, and scientists, seems to be that very little researching about ukiyoe reproduction has been done(by third parties).

(Why does carver retouch the line after all as reproducing, despite saying himself as if he would reproduce to carve the same line as the original print? Why does printer have no interested in paper and paints of the original print? What is the true concept or theory of their reproducing behind those ? Is it really what aims to reproduce ukiyoe print as it was in the Edo period, or reaches to the same quality print as it was ? In terms of the skills of the printmaking, the materials, and the sense of producing, it seems that the traditional woodblock printmaking includes not a few matters established after the Meiji period, but ukiyoe reproducing was not affected by that ?

Although it looks that every carver can carve ukiyo-e and every printer can print ukiyo-e basically, but what does the "good or bad skill" for them refer to? And what does it have to do with the reproducibility of ukiyo-e?

Is there anyone who has scientifically verified or researched such those ?

For example, one master said to me, "What's the meaning of reproducing the same ukiyoe print as it was in the Edo period with reproducing the original paper and paints, , ? I'm not interested in such that. Since reproducing are made by modern people, a long way from the Edo period, so it is natural that we should add ingenuity and improvement as modern people. Also, what everyone want from ukiyoe reproduction is as a beautiful printing , not how closely same as the original print. But, the lines should be carved to reproduce accurately since they're what directly express the artist's individuality and artistry." When I listened to him , I thought that was different matter from reproducing truly. Moreover, it seemed that he retouches the original lines in carving after all, despite saying himself should to carve accurately, since his reproducing presupposes to make a beautiful printing. When you see his working scene of tracing the line by a latest equipment to make a perfect "hanshita", and carving carefully, or if you look at the his work history, most of you would think he tries to reproduce the original ukiyoe print accurately. But, I think it wouldn't be so, but an improved ukiyoe print in terms of the skill qualities of carving and printing , the materials of paints and paper, and the conscious of production. I wonder if museum like the British Museum and researcher doing a project with him with a theme like reproducing truly, are doing it upon understanding such that? Under such idea or theory, it seems determined from the beginning that such the theme will not be achieved,,,.)

Anyway, I'm a guy who has nothing to do longer such any projects. But, I thought that leaving such kind of information might be meaningful to someone someday in the future as one perspective. (I had been angry and frustrated for over 10 years at such deceptions of ukiyoe reproducing. However, now I came to think that the most important matter is to first wish for people's happiness. Even if they are like who commit fraud without apology under authority. That's the most matter I learned in this my work, in the world of ukiyoe reproducing where even experts don't understand well.)

Note: I in the following will explain in detail the concept of my previous and this time reproducing, but as I wrote in my previous article, those on the other hand have basically another concept that is "to make as good quality as possible in how quickly and cheaply ". Also, those made for wholesale purposes, basically for businesses. So, although I'm making my reproductions based on the concept described as the following, but there are also various constraints at the same time, which make it difficult to pursue. Also, the concept, theory or idea in the following are ones I arrived at through my own considering of how to create a realistic reproduction of ukiyo-e print, and are quite different from those of carvers and printers.

ーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーー

When comparing the original and the reproduction, we could feel there is a difference in impression between the both. But, why? What makes the different impression between ?

If we look for that factor on comparing the prints, we could say the following three matters as the main factors. ・Difference in the skill qualities of carving and printing.(Roughness〜Smoothness) ・Difference in the materials of paper and paints. ・Difference in deterioration due to aging.

In order to make ukiyoe reproduction realistic (close to the original), those differences are needed to pay attention. For that, I consider the most important matter is to grasp the nuances of the original.

Explaining each point in detail in the below, but first as a premise, I have the following ideas.

"Ukiyo-e prints in the Edo period were basically cheaply and quickly being made, by hands of master and apprentices together. They are not neatly produced like today, like that skillful carver and printer carefully make a beautiful work as art with using high-quality paper and pigments."

"When we look at the original prints, we could see that although the design itself is the same, but the colors and lines often vary by each edition. However, they all have the real feel as the original. So, we could say how accurately each color and line in reproducing matches the original does not have a direct relating on whether the reproduction gets the real feel as the original."

Upon those ideas, specifically explaining the 3 points of the skill, material, and deterioration over time as the following.

ーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーー

Regarding the skill, it seems that ukiyo-e in the Edo period was cheaply and quickly made by everyone together, from master to apprentices, so there are something rough parts arised on the print. Even if it was a good quality for its time as the first impression which was carefully made, we could find out something rough parts if we look closely, like a line chipping, line distortion, misregistration of the color, paint stains, paint peeling off, bending gradation, paint overflows in the fine parts, etc. The kind of beautifully carved and printed what is almost perfectly detailed from edge to edge, as is often seen in ukiyoe reproductions nowadays, would have been difficult to produce in the Edo period.

In terms of the skill, in order to achieve the reality of the original, it is important to capture and express the nuances of such those . There are not a few reproductions that are too beautifully carved and printed, resulting in an unnatural appearance, though we can look it as the pride of modern craftsmen and that isn't what should be denied.

For example, if there were two carving versions of reproducing in which "every line carved accurately from the original, but the rough parts retouched to carve to be more beautiful lines", and "some lines omitted and less accurate, but the rough parts carved roughly and the neat parts are carved neatly, capturing the nuances of the original", I think the latter carving will get a more real feel as the original. It's as the same in also printing. I think the most important matter is whether the nuances are captured and how accurately each line and color matches the original is a secondary consideration. If accurately done , that's better, but even if undone, I don't think it has a direct effect on the realism of the reproduction.

As that example, I would like to mention that the reproductions by Enji Takamizawa and Inuki Tachihara , who are renowned for making realistic reproductions, are not necessarily accurate to the originals in terms of each line and color. I have not yet seen Enji Takamizawa's reproduction directly, but from documented sources, it is considered that it was not very accurate in terms of how closely each line and color matched the original. I consider that the characteristic or feature of Takamizawa's reproducing lied in the realism of the aging process, and Tachihara's lied in the realism of the materials use of paints and paper.

ーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーー

Regarding the materials of the paints and paper, many of the original ukiyo-e prints from the Edo period are printed on thin washi paper that has dust and residue remaining, and that the vertical and horizontal grain can be seen to some extent clearly when held up to the light. That is different from the high-quality sturdy Japanese paper from Echizen province, which has been generally using in the traditional ukiyoe reproducing nowadays, which the grain is difficult to be just visible in one direction.(It is said paper from Iyo province had been used for the most of ukiyo-e prints at least in the Edo period.) Many of the paints used originally were also different from the chemically synthesized and neatly refined pigments used today in ukiyoe reproducing .

Even today, washi like that of the Edo period, namely: The raw material, kozo, is treated with natural lye instead of chemicals. - Rice flour is added. - It is thin. - Some fiber debris and dust remain. - The kozo fibers are not too fine. - When held up to the light, the vertical and horizontal grain can be clearly seen to some extent. It isn't seemed that washi that meets all these criteria is available on the market, but it can be custom-made. However, that takes cost much. Therefore, I currently choose and use one that is as similar as possible from commercially available sources within my budget.

As for paints, although I can still prepare the paints like the Edo period to some extent , but they are quite costly. So, I now use modern chemical pigments that are commonly used among the traditional printers. Theoe can be made into almost any color depending on how are mixed. (If we assume that we know what kind of paints were used in the original prints, and what their original colors were, I think it is possible to make the colors that are almost identical to those used in the Edo period by using those synthetic pigments.)

However, I think that the softness of the plant-based paints is fundamentally different from those synthetic chemical ones. But in the end, I think they are all very similar, but not the "real thing."

Since not a few of the original paints of the Edo period tend to discolor or fade over time by their nature, so if chemically synthesized pigments that are resistant to discoloration and fading are used, that ukiyoe reproduction may tend to look unnatural over time.

ーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーー

Regarding deterioration over time, ukiyo-e prints from the Edo period are affected by aging to a more or less extent: discoloration of the paints, getting a tan of the paper, dirt, scratches, wormholes, missing margins,etc. I think such deterioration over time is one of the main factors that makes the difference in impression between the original and the reproduction.(But, that's just one of the factors. Old reproductions from the past show that just aging does not necessarily mean to make them become like the original.)

Personally, I think that the beauty of ukiyo-e lies in its taste of antique, aged quality, so in my current works I try to give it an aged look. I this time reproducing did that a little stronger than the previous.

Since I wouldn't like it to be diverted as a forgery of the original, I put stamp on the frontside of the print.

Available for sale in my webshop:

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ukiyoe Reproducing ー "Asakusa Ricefields and Torinomachi Festival, from the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo".

I thesedays done a work. It's ukiyoe reproducing from a Hiroshige's work, "Asakusa Ricefields and Torinomachi Festival, from the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo".

The concept this time reproducing was to ``make as quickly as possible at the lowest possible cost, and with the highest possible quality.'' This work was made for wholesale sale to various vendors. However, there may be some individuals who want it, so I'm also selling it on my webshop.

I used the original image from the National Diet Library Digital Collection as a reference, but my colors and lines are quite different. However, such matter is generally not uncommon in ukiyoe reproductions. Also, even if the carving and printing are somewhat rough, it does not impede the appreciation of the print, which is particularly evident in the original prints from the Edo period. Thinking the producing status and skill standards of Edo period ukiyo-e prints, and comparing the originals and nowadays ukiyoe reproductions, it seems that the rougher carvings and printing take even more reality. Nowadays, ukiyo-e is commonly viewed as art , but on the other hand, it also has originally aspects of commercial prints made quickly and cheaply and printing techniques for that. Although it from my experience seems that carvers and printers in the past placed more emphasis on speed, but I think it comes from that. Alternatively, from the Meiji period to the present day, ukiyo-e may have changed from a ``commercial print'' to an ``work of art,'' and its technique changed from a ``printing technique'' to an ``artistic expression technique.'' One old printer once said, ``There is something "play" in the print by a master.'' In my personal interpretation, it seems to me like the work of a master , that is not made with perfect care and attention to detail, but rather work that is basically done well but still retains imperfection with a sense of speed. However, note this time my reproducing is far from such that level.

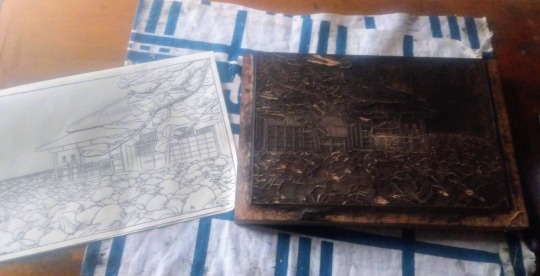

This time, I re-sharpened the previously used wild cherry woodblock with a plane and reused it. Such technique is also important in reducing production costs.

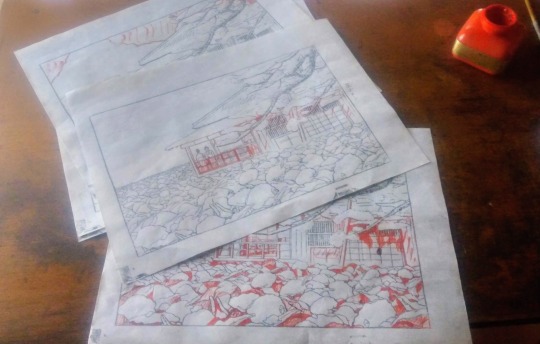

The keyblock done to carve. It's been 10 days since I started carving. Then, the necessary number of sheets are printed from this keyblock to make a manuscript for the color block, and each color block is carved based on that. I this time used woodblocks of plywood of japanese lime for that.

The all color blocks done to carve. Up to this point, 18 days have passed since I first started carving the keyblock.

I then prepared the paper for printing. It's hand-made japanese washi of all mulberry. The sizing was not drawn on this time paper, so I drew it myself. Once the blocks and paper are ready, I first do a test printing and check the blocks. Sometimes I forget to carve a part in the color blocks , so I must check it at this stage. After making a test print and checking the blocks, the final printing begins.

The total color impression is 17. I printed to make 120 sheets in 5 days. After this, l do some inspection work.

This time, I applied an aged color to only the front side of the paper since I thought that giving it an aged look would give it a better feel.

This time, the work took about a month in total, including holidays. When vendors purchase it all, this 120 sheet brings about 150,000 yen as my income. So I have to make it such quickly. Just to be clear, this is not a work of carver and printer, in terms of remuneration.

I mentioned that I made it for wholesale, but there may be people who want it personally, so I also sell on my webshop. In addition, my friend gave me the advice, ``I want one color ink line print of the keyblock since it's interesting. There might be other people who want it, so why not sell it?'' I thought that's a good idea, so I decided to sell a print of only ink line of keyblock this time.(This keyblock one not done aged process.)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Introduction about My Original Artwork of Woodblock Printing.

When I wrote my last article, what I had in mind was that I would work for income more from this year.

(What follows in this parentheses is a bit long talking that has nothing to do with the main topic of this article and this time printmaking, but let me talk.

For the past few years, I have been doing ukiyoe reproducing without considering profitability. Because, there were looked for me various contradictions fundamentally in the traditional ukiyoe reproducing. But, basically, such those issues I found seemed a kind what was difficult for people to understand. It seems difficult matter for people even to imagine, including for experts. Actually, it was difficult also for me for a long time to understand why so, why such ukiyoe reproducing done by the first class people from the very past gets fraud or contradiction easily from the early step in a project of ukiyoe reproducing. But, I now think as the reasons, that carvers' and printers' knowledge about the materials and skills nowadays includes some many that were established after the Meiji era, ukiyoe reproducing has an aspect or element as a new tradition after the Meiji era, reproducing same ukiyoe print truly as it was in the Edo era is originally out of carver's and printer's concept of skills, and researching and understanding about ukiyoe reproducing has not been developed so much that such those are recognized well. Therefore, contradictions or frauds would inevitably arise from those.

Anyway, putting aside such my opinion, but please compare and observe the prints of the original and the reproduction more than anything. And please get to recognize the differences between the original print of the first edition and the reproduction of that, in terms of the materials use as paints and paper, and the skill qualities of carving and printing as line chipped, line distortion, color misregistration, color grazed, etc. Because, that seems to be very important to understand what ukiyoe reproduction is after all.

I'd like researcher or scientist particularly who relates a ukiyoe reproducing project to clarify such those differences between the original and the reproduction by doing comparative observation, as the basic knowledge for reproducing. And also to look and verify carver's and printer's theory of ukiyoe reproducing. Why does he retouch the line finally despite he traces it from the original very carefully using a latest equipment saying himself as if he tries to reproduce the same line? Why does he have no interested in the original paints and paper of the original of the Edo era? Please look and verify their theories behind those matters. Is that really what focuses on reproducibility or results to same ukiyo-e print of the Edo era ?

I consider the fundamental cause why ukiyoe of the Edo era have not been able to reproduce truly is that organizing concepts or theories is not done properly with verifying among persons who relate a project of ukiyoe reproducing, not lacks of the materials and the skills of carver and printer nowadays. Being adopted a theory which promise from the first to be making an modern improved ukiyoe print inevitably is the most cause why not done truly, I consider.

Talking a little long, unrelated the main topic of this article. But I as 19 years old started to do woodblock printmaking. I then became a printer, having a will which I someday in the future would reproduce ukiyoe in the truest sense, but such my idea was too different from the concept or theory of the traditional ukiyoe reproducing. So, I quit a printer and worked for it individually, but that was difficult to make a living. And I in the last year decided to put a period to such my work, but, as the period, what I left to say was such like that.)

Anyway , now let turn the main topic that is the printmaking this time.

So, when I thought about income, I came to think that if for income, is it better to make a something original print with ukiyoe or shi-hanga style than reproducing? In actual, such kind of wood block prints has recently been produced frequently by various publishers. So, I this time tried to make such one.

Concerning specifically what I made, I from the past have had an idea that something nice print could be born if I make woodblock print from a vintage photo postcard as the following, which began to be frequently produced about the turn of the 20th century. So, I this time put it into action.

Concept of this time printmaking is "making a nostalgic and beautiful print". For me, one of the charms of ukiyoe and shi-hanga is nostalgia, showing the old days.

But, what is more important than that as the concept is making a beautiful print.

Although I already mentioned about income as the background of this time printmaking, it seems important for that to make a beautiful print which makes people happy to appreciate. Actually,Ididn't have such idea so much in my past reproducing work, because reproducing same ukiyoe print thoroughly seemed for me essentially different matter from making a beautiful ukiyoe reproduction.

About the Design

This time I was inspired from this postcard and made the design. I'm not sure when this postcard was made, but since the postmark is 1939, so it would have been made around that year. It shows Shinobazu Pond with lotus flowers blooming in summer, in Ueno Park.

About the Materials

As woodblocks, I used a cheap cherry one for the keyblock. And, katsura and japanese lime for the color blocks. I didn't use expensive hard cherry wood block of good quality, because even those cheap wood blocks I selected seemed to be enough for the expression this time, and also l didn't have an idea to print in a large quantity.

As paper, l used handmade washi which I bought a little long time ago and left. Not sure though, it would be mulberry with pulp. I selected it thinking it responses enough for making a beautiful print.

As paints, l used chemical ones which a traditional printer nowadays has been using generally for reproducings of ukiyoe and shin hanga.

About the Carving&Printing

I didn't pursue too much the skills like which carver and printer normally do nowadays, particularly as the following.

·Carving lines without chipping.

·Carving smooth lines.

·Printing without color misregistration.

·Printing without paint grazing.

·Printing without paint accumulation ("tamari").

·Printing without paint stain in a superfluous area on a print.

The reason why I so was just for the expression, just for the taste of the print this time. But, as a premise of that, I have an idea as the following.

Such those kinds of carver and printer skills relate to beauty just only until a certain level.

What I mean is, when we look the original prints of ukiyoe and shin hanga (not reproductions at the present), there are many beautiful prints in spite of such skill matters aren't done so well. Especially in ukiyoe of the Edo era, it's normal it has some roughness parts in its skill quality. But, that seems natural matter, thinking that it in the Edo era had been produced very speedy by several hands from master to apprentices together. And also, since the skill level of carver and printer advanced around the Meiji era, a case also happens which even it was normal or good quality from the perspective of people of the Edo era, it looks to have noticeable roughness parts from nowadays. Even it's the first impression of the first edition which was careful made in the Edo era, it seems to have roughness parts usually if we look closely.

Also in the shin hanga, it doesn't seem rare that it has some roughness parts in its carving and printing if we look closely, though those would have been basically done as intentional expression in the case of shin hanga.

So, anyway, how much are such roughness parts in carving and printing related to the beauty of the print?

I think the first edition made carefully is more beautiful than its later edition made roughly. But, it's not rare even such first edition has some roughness parts.

And, is the beauty of that print spoiled by those roughness so much? Or, would the image become more beautiful if those roughness are well fixed in reproducing? I don't think it's either.

Therefore, it seems for me that the high skills of carver and printer relate to beauty of a print just only until a certain level, and unrelated over that level.

I this time printed 26 color impressions.

About Sale

Printmaking this time was so fun and comfortable. From the early step of the process, I could get something good feeling that a nice print could be born naturally, and also various nice images for the next prints came to my mind. However, whether I'll continue this project or not depends on its earnings.

Title: Ueno Park, Tokyo, 7, 1938

Paper size: 29×20.5 cm

The circulation is 23 of a limited edition. You perhaps wonder why it's such a small quantity. But, it's enough many from my sale ability at the present. I would make it more in the future new prints if people who would like to purchase my prints would appear in the future. But, in actual, if there were 20〜30 people who would like to purchase my prints around the world, that's Really enough for me.

It's available for sale in the following link.

If it would not be sold well, I will start again to make ukiyoe reproductions for vendors, as I had been doing in the past temporarily. That's not a work with publisher since I quit a printer years ago and not a carver from the first. That is a work which making in a large quantity in a cheap price while saving cost. But, that is what should be reached to an average level of ukiyoe reproduction in the market. That is a rewarding job also.

(I mentioned in the previous article, that I from this year would make ukiyoe eproduction including current condition. But I decided to stop that due to the sale risk. )

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shift in My Activity

On the way I worked as a printer, and looked through various literatures and ukiyoe reproductions which have been produced by the traditional wood block printmaking manner and society, I strongly came to feel that the skills of carver and printer, and the reproduction are not what focus on reproducibility truly for the original ukiyo-e print of the Edo period.

And when I in the prints searched for the factors what make the reproduction so, in other words, what factors cause different impressions between the original and the reproduction?, I came to think that the main are differences of materials use of paints and paper from the original, and being the skill quality of carver and printer nowadays higher advanced and sophisticated than the original.

(Plus, there is also the issue of deterioration over time, but there are many cases where even old reproductions that have deteriorated pretty much can be identified easily as "this is a reproduction'', so deterioration seems to be just a secondary factor.)

Also, in addition to those, even experts looked to tend to confuse "making a improved beautiful ukiyoe print" by using modern improved paints and washi paper, and higher skill quality of carving and printing than the Edo period, with "reproducing the same ukiyoe print in the Edo period truly". It looked that being understood for the reproduction falls too far into impression theory just on partial matters, and researching for ukiyoe reproduction and organizing concepts properly with verifying haven't almost ever been done historically, exists as the major factor also.

For example, I think many people get the impression from looking the work scenes of carver and printer, or the titles of the organizations, that they aim to reproduce the same ukiyo-e prints truly from the Edo period. However, if you look carefully at the reproductions by them during this past 100 years, you would see that was not so. Alternatively, you can find it out by carefully researching the literatures.

However, so far, systematic organizing of the concept about such that has hardly been carried out. And if we just limit ourselves to such impression theory, the issues as like following will be overlooked:

・Problems that have historically existed in the ukiyoe reproducing.

( I from the first place wonder how many people, including experts, recognize contradictions or injustices in the reproducing ?Looking at a work scene that carver traces the lines from the original ukiyoe print so politely and carves so carefully with it on a very fine cherry woodblock, many people would get to think he tries to reproduce the same line or same print as the original in the Edo period. But, looking the finished reproduction and comparing with the original carefully, you could probably notice what he aimed to make wasn't the same line or same print, but more beautiful line with retouching or improved print by carving more beautiful line and printing more beautifully with modern pigments and washi paper that were improved nowadays. So, what did he try to make in actual ?Isn't there a contradiction between your impression and the actual product ? That's where I see the problems.

I think ukiyoe of the Edo period, even in the first impression of the first edition which was carefully and skillfully made, has some rough parts in the quality of carving and printing, because it basically was what so speedy made for low profit high sales, by hands of guys together from master to apprentices, and the skill level of carvers and printers was advanced particularly around the Meiji period(in other words, the rough parts seem to be more noticeable from the perspective of modern carver and printer, even if it was a good quality from the perspective of ones in the Edo period).

However, I think such rough part is a feature of ukiyoe of the Edo period and seems to relate to the reality of reproduction, so shouldn't be ignored when reproducing.

For truly reproducing, I think ukiyoe reproduction is necessary much more to be researched as comparing with the original print, and clarified the differences from the original, in terms of the materials use of paints and paper, and the skill quality of carving and printing, since those seem to relate directly to the reality of reproducing, rather than relying solely on the subjective opinions of carver, printer or publisher. )

・What is necessary in the reproducing in order to substantially reproduce Ukiyo-e from the Edo period?

(At least, I do not think that is just the skill of carver and printer. Because every carver can carve ukiyoe and every printer can print also, as basically. No matter how high printmaking skill he has, original ukiyoe prints are not seemed to be able to reproduce truly just by such that, looking the past reproductions. )

・The traditional carver's and printer's knowledge about the skills and materials use may not include some many that were established after the Meiji period?

(For example, looking at shin-hanga prints, etc. from the early 20th century, you could notice there are advances of printmaking skill, materials use and concept of production from the Edo period. And such those are reflected to also ukiyoe reproducing nowadays?

I think the traditional ukiyoe reproducing nowadays includes elements as a new tradition established after the Meiji period, in terms of the skill quality of carving and printing, materials use and concept of production. So, that way is to be necessarily variously contradictory in reproducing the same ukiyoe print of the Edo period. )

・And so on,,,,

And even the experts looked to be in such that overlooking situation.

(Hopefully, I'd like a researcher to research about the differences between the original and reproduction, especially in terms of materials use of paint and paper, and skill quality of carving and printing such as chipped line, distorted line, color misregistration, grazed paint and so on, by comparative observation of the original and reproduction. Because, those relate directly to reproducibility and are basic knowledge which should be known for reproducing, but appeared not to recognize well even among experts.)

So, I researched the materials and the skills of truth of the original print in the Edo period, and tried to organize the concept of reproduction comprehensively and systematically for these years. However, due to various circumstances, mainly problem of income, I decided to change the axis of my activity to the following two points for the time being.

One is that I'll go to a reproducing way, " reproducing with aged processing". Please refer to the previous article about this way.

Two is that I'll do a business as ukiyoe dealer, mainly sell reproductions produced in the 20th century.

Those prints are sold in my web shop in the following link.

As I am writing this article, there is no lineup of my reproducing artwork of "reproduction with aged processing", but I'll introduce it on my blog when the print is completed.

0 notes

Text

About Reproducing of "Awa Province: Naruto Whirlpools (Awa, Naruto no fûha), from the series Famous Places in the Sixty-odd Provinces (Rokujûyoshû meisho zue)".

I these days made a reproduction in collaboration with Cool Japan, a Japanese goods store in France.

So I would like to introduce the reproducing process in this article.

The original print was designed by Hiroshige Utagawa in ca.1855.

①Concept

The concept of this reproducing is completely different from the one I have introduced so far in this blog, and it is a "reproduction including aging."

In particular, for this time, I assumed the original print that is in good condition .

②About the original picture.

The original picture was selected from an art book, which seems to be the first impression or close to that. That is judged by the degree of wear of the key block line or the number of colors. The closer to the later edition, it tends that the more the lines become worn out and become softer, more crumbly, and the more colors are omitted.

(At least in Japanese law, there basically is no copyright in ukiyo-e from the Edo period, but depending on the photography method or editing etc. used as making ukiyo-e art books etc., the copyright of the person concerned is occurred. Some ukiyo-e art books are marked with a prohibiting copying or reproducing , but I do not to use such items. However, depending on the sources of collection, there would be where even if they did not express their intention to prohibit copying when they published the art book in the past, but they at the present do so and request the application as copying from their past art book.)

Although I have not had any direct touching experience with the original print of this time, but I own the original print of "Tôtômi Province" from the same series, that is a later edition with good condition. So I used that as a reference when determining the texture of the paper or the degree of aged processing.

③About the materials

The woodblocks are usually made of wild cherry , but due to budget constraints, this time I used magnolia and china veneer woodblocks, which are softer than wild cherry woodblocks.

The paper I used this time was selected from among the washi papers that are generally available on the market, that is cheap but looks like that as much as possible.

At that time, I paid particular attention to the thinness of the paper.

Generally, original prints from the Edo period are often used thin paper, unlike contemporary reproduction prints. The aforementioned "Tôtômi" which I used as a reference this time was also a paper so thin that it was difficult to hold it normally.

I chose such paper for this reproducing.

And, I used modern chemical pigments that are commonly used by the printers for reproducing.

④About carving and printing

What I was especially careful about was not to make the print beautifully according to the sensibilities and skill standards of modern carvers and printers, but to match it to the skill level of the original print. In reproducing by modern carvers and printers, mistakes in the original prints are often corrected, and it is common to be made more beautifully than the original.

However, looking back at their reproductions that have been made so far, I consider that such advancement in skill standards is one of the main factors that makes the difference of impression between the original prints and reproductions. Considering that ukiyo-e prints in the Edo period were produced speedily at a low profit high sales, everyone from the master to the apprentices were involved for making one work, the skill level of carvers and printers improved significantly since the Meiji period, and so on, I think even in the first impression of the first edition, there are to be roughness parts, in ukiyoe of the Edo period. And such roughness is a characteristic of the skill of ukiyoe of the Edo period, I think.

(In addition to that, I consider other factors are the differences of the materials of paints and paper, and aging. And, since even if an old reproduction which has aged considerably over time, there are many cases where it is possible to tell that it is a reproduction, so I think the difference in aging is a secondary factor, and the primary factor is the differences in the materials and the skill quality of carving and printing. )

In this reproducing, I tried to reproduce as much as possible the technical mistakes found in the original print, as long as they do not cause any major hindrance to appreciating.

However, there were some that didn't go as I thought due to my lack of skill, and especially in the carving, I wasn't able to follow the lines of the original print in so details since I used soft woodblocks as mentioned above.

⑤ After finishing the production

When I asked a acquaintance of mine, who is an ukiyo-e dealer, to look at the completed reproduction, he commented "I feel the color of red, the hardness of the paper, and the hardness of the colors are different from the original print. But for a moment I thought it was the original, and I don't think an ordinary people would be able to tell if it's an original or reproduction. "

This reproducing is limited to 33 copies and only handled by Cool Japan.

To prevent it from being misappropriated as a forgery, I this time added a little large blank space at the bottom of the print and put my signature there.

Note that this work had undergone aging processing. It has like the same level of dirt or damage as the original print, which can be said to be in "good condition", so please be aware of this before purchasing.

For order inquiries, please contact Cool Japan in this link,

0 notes

Text

”What is the Ukiyoe Reproduction?” part 3. Asking Mr.Motoharu Asaka,a carver.

About 15 years have passed since I got involved in ukiyoe reproducing, but during that time I have encountered many misunderstandings about the ukiyoe reproduction. It can be said that such the situation was rather general. So far,I have written articles on the theme of "What is the Ukiyoe Reproduction ?", but this time, for the third time, I interviewed a carver.

Since systematic research on the reproduction is still underdeveloped, the important matters to understand about the reproduction are to research literature, look at the reproductions carefully enough to make comparisons, listen directly to carvers and printers about the truth of production.

This time, I interviewed Mr. Motoharu Asaka, a carver. My first encounter with Mr. Asaka began about 15 years ago when I attended a woodblockprint making class hosted by him. The other day, I after a long time received a call from him for some tasks, so I requested him an interview that I had been thinking about from before.

In this article, I compiled centered on Mr. Asaka's views, about his thoughts on the reproduction, what he is focusing on when reproducing, and what excellent reproduction or excellent skill is. In addition, he has a deep knowledge of not only carving but also printing, so I asked him about printing also.

I interviewed Mr. Asaka at his studio, ”Takumi Mokuhanga Koubo (匠木版画工房)” , located in Tokyo, in June 2023.

Mr.Motoharu Asaka Biography (Excerpt from the official website of his studio. For further details, please refer to the same link though Japanese language.) 1951 Born in Shizuoka Prefecture.

1962 Began making woodblock prints, while a student at elementary school in Tokyo.

1967 Received instruction in the traditional woodblockprint making from Mr.Tadao Takamizawa (Note 1), while a student at high school in Tokyo.

1968 Became an apprentice to Mr.Kojiro Kikuda, a carver in Kyoto.

1985 After 17 years of training, became an exclusive carver at Takamizawa Institute.

1999 Established a studio together with Mr. Satoshi Hishimura, a printer in Nishi-Waseda, Shinjuku,Tokyo.

2011 Moved the studio to the current location (Tomihisa-cho, Shinjuku). In addition, many demonstrations and lectures in Japan and overseas.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

Yuya : “Thank you very much for your time today. At first, I would like to ask you to tell about your thoughts or mind about the reproducing. ”

Mr. Asaka: “I from childhood was interested in making woodblock prints, and when I was 16 years old, I by chance started to receive instruction from Mr. Tadao Takamizawa. Not long after that, Mr.Tadao recommended me to become an apprentice to Kojiro Kikuda, a master carver in Kyoto who was working with Mr. Tadao at the time. At that time, I was aiming to go on to an art university, and my high school teacher and others around me were against it, so I was very worried, but eventually I made up my mind and went to Kyoto for training at the end of the summer vacation of my second year of high school. Although I from that time on was indebted to Mr.Tadao, but after becoming independent as a carver, I became an exclusive carver at Takamizawa Institute.

Mr.Tadao was a guy who instructed, as using a magnifying machine to compare the original ukiyo-e print from the Edo period with the reproduction that I carved, " Look, the 36th dot from the right and the 16th dot from the top have different shapes, and the tip and belly of the brush strokes are also different."

Although Mr.Tadao's older brother, Enji Takamizawa, made such an elaborate reproduction that it was said that it was difficult to distinguish from the originals, even when compared side by side, but that will was passed on to Mr.Tadao, and also me. That's my origin. Not only in ukiyo-e reproducing, but also in Japanese paintings and Western paintings reproducing, my motto is carving out lines that are faithful to the original and are indistinguishable from the original.

Yuya: "What kind of things do you focus on in particular when ukiyoe reproducing?"

Mr. Asaka: “One is, as I just said, to carve lines that are faithful to the original print, and the other is to carve “live lines” that are sharp and momentum. In the Edo period, the line drawn by the artist was just a guideline, and the carver used that as a guideline to create the lines that "live lines ". For example, Hokusai's block copy in his later years has severely disordered lines, but the carvers at that time did not carve it as it is, but while fixing with conscious of the sharpness and momentum of the line so as to make the best use of Hokusai's line. However, reproducing in future generations, we have to carve it so that the lines are accurately traced because it is a duplicate. And if we carve it like that as carefully tracing, it will be difficult to create sharp and momentum lines.

That's where the difficulty lies. It is that we must study for decades to be able to carve lines that are sharp and lively while carving as if tracing accurately. No matter how faithful lines we carve, if the carved lines are not sharp and momentum, it is meaningless.

Yuya: “Regarding that, although it seems that there are not a few lines in ukiyo-e prints in the Edo period, that are lacking sharpness and momentum by disordered or chipped, do you think such parts should be corrected in reproducing? ”

Mr. Asaka: "I think that such lines disturbances should be corrected. However, at that time, for example, if it is Hokusai's print, I compare the prints in multiple art books, etc., and make corrections while assuming that Hokusai's line would be like this if it was carved well. It's no good to go away from Hokusai's line by retouching it beautifully on your free. I think the chipped lines should also be corrected if they are not intentionally expressed as the joints of the brush strokes.

Yuya : "Thinking about the characteristics of ukiyo-e prints in the Edo period, and the skill level of carvers and printers in that period,etc, I think that if it is to be faithfully reproduced, the disordered and chipped lines should be reproduced as they are to some extent.

Mr. Asaka: "Mr.Tadao had a similar idea as that , but the problem around that is a difficult one. Some carvers carve while omitting the lines of the original print though I don't approve of that idea, but in the end, the ideas and interpretations in carving are different for each person.

Yuya: “What do you think are the requirements for a master carver?”

Mr. Asaka: " To be able to carve lines that are faithful to the original, while at the same time being sharp and lively. To carve fast is also important. If the carving is slow, I don't think he is a master."

Yuya: “About printing, what do you think about the conditions of excellent printing, excellent reproductions, and a master printer ?”

Mr.Asaka : "I think that one is natural and smooth gradation can be printed, and the other is "gomazuri" (printing with grainy and mottled colors like sprinkled sesame seeds)is not be done except for special exception works. In addition, to be printed without misregistration of color blocks, but I think that is the most basic of basics.

Also, if he is to print 100 sheets, all of the 1st to 100th sheets should be uniformly finished. Like an example as, there is no difference in the thickness and density of the gradation when compared the 1st and 100th copies .

And, just like the requirements for a master carver, it is also important that the speed at which he can print fast, at the same time, not spare effort. A good job is taken time and effort, for examples, dark-colored gradation is printed not once, but in half the density, and printed twice to be more beautiful, or in order to print the outline of woman face finely,the entire paper in advance is rubbed from the back side and is to be stretched thin.

Yuya : “In regards to those, although there are many ukiyo-e prints from the Edo period that were poorly printed, do you think that such those mistakes should be corrected when reproducing ?”

Mr. Asaka: “Of course. There are many ukiyo-e prints from the Edo period that are rough-printed, but on the other hand, I think there are not a few ones printed carefully, which belong beautiful first-class prints, even though they have few opportunities to be opened. When reproducing, the first class one should be used as the original. If we can't do that, and if we use the second or third class one, I think it's important to reproduce it assuming careful and beautiful printing of the first class one .

Yuya: "If there are parts that are not printed well in spite of it is the first class original print, do you think they should be corrected?"

Mr. Asaka: “Of course. The first one would have been printed by a master, so there must be no mistakes such as color misregistration or gomazuri, but if there are some mistakes, they should be corrected in reproducing. I think it's strange to reproduce those mistakes as they are.

Yuya : “On a different note, when looking at various reproductions, there is not a few done aging processing, such as fading color and staining the paper intentionally. However, it seems that reproductions tend not to be done such aging processing as the periods go down to the present. Why do you think it is? ”

Mr. Asaka: “Although I think one of the reasons is that doing the processing takes time and effort, but more than that , it is because there is no one to ask for it or supervise it.There is also no one who has eyes to appreciate such that.”

Yuya: "If you have any goals for the future, please let me know."

Mr. Asaka: “Although I have been training some disciples, I want to pass on the skills I have cultivated to future generations. Also, I want to make an environment where my disciples will be able to make a living. Specifically, I am thinking of commercializing my studio and publishing as a publisher. The same goes for ukiyo-e, but besides that, I want to make use of high woodblockprintmaking skill to publish various works. I want my disciples to move forward with their hopes and goals. I hope that they will become master carvers who can carve sharp, vigorous and faithful to the original lines with fast speed.

My master (Mr. Kojiro Kikuda) was a guy who would not take a cheap job for the sake of his disciples or money, saying our hands would become dull if we would do such.He was the kind of guy who selected and made us use well-carved original pictures or block copies for our training.

I as well make my disciples use the carved of master carvers rather than poor skill originals or block copies. I want them to sharpen their skills by carving and carving while acquiring a discerning eye by looking at a lot of good works.

Yuya: "It was a valuable talk. Thank you very much for today."

Reference

(Note1)

・高見澤たか子「ある浮世絵師の遺産―高見澤遠治おぼえ書―」(東京書籍株式会社、1978年 )

・吉田暎二「浮世絵事典 中巻」(画文堂、1990年、167~168頁)。

・中村暢時「高見澤版複製浮世絵の歴史」(「浮世絵備要」、自家版、2000年)

・畑江麻理「大正期「複製浮世絵」における高見澤遠治 : その卓越した精巧さの実見調査と 、岸田劉生らに与えた影響の考察」(「Lotus : 日本フェノロサ学会機関誌」39号、日���フ ェノロサ学会、2019年)

0 notes

Text

Restorative Reproducing of Ukiyo-e Print,partⅡ, taking the example of Utagawa Kunisada's print.

I used to be a traditional printer, but I was influenced by Mr.Inuki Tachihara's reproducing work, and I have been reproducing by myself, including the materials such as paints and paper of the original ukiyoe prints in the Edo period.

If reproducing is done according to the methodology of a traditional carver and printer, the finished print as a result has a strong character as "an improved product". Even if it is made with the cooperation of first-class carver and printer, first-class museum and ukiyo-e researcher, it is to be what has various contradictions as an accurate reproduction woodblock print at the substantial aspects of producing and finished product. Aiming to make a beautiful print by a higher skill level of carving and printing than in the Edo period, using improved modern color materials and washi paper as they do, seems to me that it is fundamentally a little different from aiming to reproduce the print of the Edo period truly.

I departed from such conventional way of reproduction, and I have been working on reproducing with the theme of "reproducibility", which is as reproducing ukiyoe prints as the same quality as those that had just been printed up in the Edo period, both in terms of materials, and the skill level of carving and printing. And I named that "Restorative Reproducing".

This time, I've just completed the second work, so I would like to introduce the details. (The previous article about "the Restorative Reproducing, partⅠ" is available in the following link.)

The following is a description about the reproducing this time.

①About the original print.

It's "New Higurashi (Shin Higurashi):Double Blossoms,Single Blossoms,Mountain Cherry (Yae, Hitoe, Yamazakura),from the series Cherry-blossom Viewing Spots in Edo(Edo hanami tsukushi)", by Utagawa Kunisada.

It is my personal collection that I purchased from an ukiyo-e dealer.

Regarding the year of its publication, the ukiyo-e dealer said, "It is difficult to specify, but it is about mid-Tempo.The time of printing is relatively close to that of the first edition".

However, as described below, when the paints were analyzed at a later date, the use of prussian blue was not detected, and indigo and aobanagami were detected as blue paints. Therefore, it was also thought that the possibility that it was before the early Tenpo era was high.

②About the paints.

Not a few of the paints on ukiyoe prints cannot be judged or are difficult to estimate with the naked eye, so doing scientific analysis to the original print is useful for the reproducing. I asked Mr. Takuji Yamada of Ryukoku University for this time paints analysis, and the analysis methods this time were microscope magnification observation, fluorescent X-ray analysis, visible reflectance spectroscopic analysis, and infrared camera.

As a result of paints analysis, the following paints were estimated to have been used at each part in the figure below. (Each number corresponds to that in the figure.)

01ーsafflower 02ーred iron oxide 03ーindigo and orpiment

04ーsafflower 05ーindigo and orpiment

06ーindigo and orpiment 07ーsafflower and aobanagami

08ーsafflower and aobanagami 09ーindigo and orpiment

10-safflower 11ーsumi 12ーred iron oxide 13ーsafflower

14ーsafflower 15ーorpiment 16ーsafflower

Based on the results of this analysis, the paints used for the reproducing are as following.

Sumi: I used the current Suzuka sumi of oil soot by the soaked sumi method.

Orpiment (artificial) : Based on recent research about artificial orpiment in ukiyo-e prints, the orpiment in this original print is natural one. However, since I couldn't procure natural one for this time, I used artificial.The production of artificial has already been discontinued in Japan, but it seems that it was still being produced at least at the end of the Showa era, and this time I obtained the stock of that time and used.

Safflower: I used safflower cakes as raw materials made at "大賀藕絲館" in Machida city,Tokyo, and made safflower paint by myself referring to the book,大関増業編, "彩色類聚巻之下",1817. When I used the paint, I used acid solution of plum.

Aobanagami: I used one produced currently in Kusatsu city, Shiga.

Red iron oxide: From the analysis result, it was estimated to be red iron oxide of sulfate of iron. So,I used one by the current 西江邸 in Fukiya , which is made by burning and splashing sulfate of iron made from iron pyrrhotite ore, as like in the Edo period.

Indigo: Indigo is used in the original print ,which can be seen as indistinguishable from prussian blue with the naked eye. Judging from the date of publication of the original print,it is probable that this was made by the extraction method by boiling indigo-dyed cloth with lime and starch syrup.But,in this reproducing,I used a mix of the three as the following, "made by myself using ready-made indigo dyed yarn by the method above", "made by the bubble of indigo dyeing solution by lye fermentation", and "ready-made chemically synthesized pigment" .

This reason is that I in the middle of this time reproducing had the opportunity to receive an indigo bubble from Mr. Ranshu Yano, an indigo dyer in Tokushima,and I also wanted to confirm the following assumptions based on my own experience of doing the extraction method by boiling and researching of literature until then.The assumption is ,“both the methods of indigo bubble and the boiling leave dullness in the finished paint, and the former method is duller than the latter.But those dullnesses are due to the lye content, and the lye-removing operation in the process will eventually give them both a clear blue color."

However, due to the amount of raw materials in the experimenting and the result that although the removing of lye from both methods increases the bluishness of the color, but it seemed that it would not become a prussian blue color as like the original, so I needed to use chemically synthesized pigment when printing. At this time, I haven't figured out how to make the indigo paint like prussian blue, which existed in the Edo period.

In addition, when I used sumi,orpiment,red iron oxide and indigo,I mixed with cowhide glue that does not use chemicals or additives. In addition, I added starch paste when I was printing 12 (red iron oxide) ,07 and 08 (safflower and aobanagami) parts . (There is an old book that mentions paste was not used in the past. Based on the color texture of the original print, I felt that no paste was necessary, so I basically decided not to use paste. However, when printing those parts, I decided to add paste due to those color textures when I actually printed it. )

③About the paper

The dimensions of the original print is about 25×37cm.

When analysing the paints mentioned above, it was found that the paper of the original print is mulberry paper containing rice flour, but I couldn't carried out further investigation at this time.

I have had Mr.Ryoji Tamura,a craftsman of Tosa Washi,make custom paper that has the characteristics that are considered to be somewhat common in ukiyoe paper in the Edo period, and I used this paper for reproducing this time.

The characteristics that are held down are:

1:To be thin. 2:To be tosa mulberry paper. 3:To use natural lye in boiling mulberry process. 4:To contain rice flour. 5:To make the grain of the paper, which can be seen when the paper is held through the light, cross the short side of the paper finely with respect to the long side. 6:To leave a certain amount of dust or dregs of mulberry in the finished paper.

However, regarding 4, the amount of rice flour added was set at 50% against the raw material weight of mulberry. This is the average value when I asked the Kochi Prefectural Paper Industry Technology Center to analyze the paper of six ukiyo-e prints from the Edo period.Also, regarding 5, due to the nowadays papermaking tools, it is not reached the state of the general ukiyo-e prints in the Edo period.

When using paper, I did sizing . The glue is the same as mentioned above, and the alum was made by myself from aluminum sulfate and wood ash, referring to the method of making artificial alum in the Edo period.

④About carving and printing.

I used four woodblocks of mountain cherry.

In the society of the traditional carvers, it is not uncommon for the lines of the original prints to be omitted when reproducing.Or, even if he says,"I carve and reproduce lines that are completely faithful to the original as being indistinguishable from the original", it does not mean to carve and reproduce the same lines as the original as if it is like a copying at face value.

In that ,it seems that there is a lot of implication included, that "I do not omit the original lines, but I make corrections to the parts that are not well carved such as broken lines and chipped out lines to make the lines more beautiful than the original ."

It also seems to be like "recreating of an idea (which doesn't exist on the original print in front of )" of each ukiyoe artist's line as Hokusai's , Hiroshige's and so on.

Whether it is the former example or the latter example, in the society of the traditional carvers, it seems that carving“alive line”which is sharp and vigorous exists as one of the important values.

Such kinds of skill value also exists in printers, and if we do reproducing according to the methodologies of the traditional carvers and printers, various contradictions will arise in reproducing focused on reproducibility.

Apart from making the same prints as the original prints, in a way that contradicts that, there seems to be the senses of values regarding the skills in the traditional carvers and printers.

But in my opinion, since it seems that craftsmen from poor skills to good skills were typically all-together involved as making for one ukiyoe print in the Edo period, and many of ukiyoe prints are said to have been sold as the price of a bowl of soba noodles, so it seems that it was impossible for one ukiyoe print to be carved and printed well from corner to corner, and it is natural that there are some parts that were not carved or printed well. Even if in the first class impression which was carefully made, if we look closely the original print, we could find technical mistakes in carving and printing such as chipped lines, color misregistration,etc.

Even if there was a ukiyoe print that has no such technical mistakes, I think it is a "special exception", and considering the skill standards of carving and printing in the Edo period,I don't think it should be standardized. The skill standard of carvers and printers seems to have changed by the periods, and it seems that it became more advanced especially around the Meiji period. When reproducing ukiyo-e prints of the Edo period, I think the skill level of the carver and printer in the Edo period should be considered and taken, not the level of the modern carver and printer after having undergone such advancements in skill.

Even if it's the first impression, the original ukiyoe print has some rough parts in carving and printing quality, but those are features of the ukiyoe of the Edo period, so shouldn't be ignored as reproducing, I think.

In addition to those, although it is not SoetsuYanagi's thought, I feel that the parts on the original prints, which are not well carved or printed are also deeply related to the original beauty of ukiyoe prints in the Edo period.

Putting aside such the subjective question of whether it is beautiful or not, since the goal of this reproducing at least was to "reproduce the same quality as the original print which is just printed up in the Edo period", so I dedicated to reproduce the parts that are not well carved or printed on the original print as they are, as long as they did not very interfere for appreciating.

⑤About comparison photos.

It is often difficult to convey the reproducibility of a reproduction unless a comparison is done with its original print.

Although there is not a few parts that I couldn't reproduce well due to my skill problems, and such the texture of the paper can't be conveyed, but I put some copies of the original and my reproduction so that you could use as a reference for comparison in somewhat.

the original

my reproduction

backside of the original

backside of my reproduction

In the following each photo, the above one is the original and the below is my reproduction.

0 notes

Text

I will explain detailed info at a later day.

1 note

·

View note

Note

Hello! Is it possible to order a specific ukiyo-e?

Hi. Sorry for the late reply. I was using an older version of the app, so I missed your notification by something system error.

Thank you for reading the article. You must have a beautiful garden. Whether you can order depends on that content. If you are still interested in ordering, please tell me more about it.

0 notes

Text

Paints of Ukiyo-e - Aobanagami③ - Lecture Report, “About the Use of Aobanagami in Ukiyo-e ” .

In the spring of 2022, I was gaven to lecture about the use of aobanagami in ukiyo-e, as part of the seminar by the Kusatsu Aobanagami Manufacturing Technology Preservation Society.

I report that on this article.

(The following is the contents of the lecture at that time.)

"I this time talk about the use of aobanagami in ukiyo-e prints in chronological order of the history.

Ukiyo-e in the Edo period basically consists of handwriting and woodblock printing, but what I will talk about this time is wood block print which originally started as an illustration in a printed book and eventually became independent as a single print. It was around the end of the 17th century that the illustration became independent as a single printing. In the early stages, the ink outlines were printed on a woodblock, and the colors were hand-colored using brushes, but around the early 1740s, multicolored printing began to be used. This is called Benizuri-e in the category of Ukiyo-e prints, and it is a multi-color print of about 4 or 5 colors, in which the outlines are printed with sumi ink, and red, indigo, green, etc. are used there.

The blue paint in this Benizuri-e period is basically genuine indigo derived from plant indigo, but there is a scientific analysis research that confirmed the detection of aobanagami in Benizuri-e works about 1760. So, as far as it is empirically confirmed, about 1760 is considered to be the earliest time of introduction of aobanagami in ukiyo-e of single print.

However, as far as I have confirmed, it is only a guess, but the earliest example looks to have already been used about 1730 when before Benizuri-e was invented. Since this is only a judgment by the naked eye of mine on the art book, that is a matter which I'll hopefully do a paint analysis research in particular in the future.

A short time after that, about 1764, multi-colored printing called "mizue" , which is also a small number of colors and used the blue of aobanagami instead of sumi for the contour lines of the keyblock, became popular for a while and aobanagami was frequently used. It is probable that around that time, a market system was established in Edo where aobanagami was supplied at a relatively low price.

From historical materials related to the Zeze domain in the Edo period, it is considerd that the production of aobanagami was expanding around Kusatsu in the latter half of the 18th century when aobanagami began to be used in ukiyo-e, and this is considered to relate to the introduction of aobanagami in ukiyo-e.

But, since long before the Edo period, ordinary Tsuyukusa, which grows wild around the country, seems to have not been distinguished from Aobana in terms of its name or purpose of use. For example, a documentary material from the end of the 18th century, said the raw material "Utsushiki no Hana" as a method of manufacturing Hanadagami which is another name for Aobanagami. Utsushiki no Hana is said to be one of the Kyushu dialects of Tsuyukusa. In other words, it seems that the manufacturing method of aobanagami was known to a certain extent of wide area at least till that time.

Therefore, in the late 18th century, Aobanagami was also produced in the Kanto area, and the possibility that it was introduced into Ukiyo-e is considered low, but it may be. Also, in the Nagano area, there is a dialect called 'kamisomebana' as theTsuyukusa dialect, and it is associated with flowers used for dyeing paper, that is aobanagami.

As far as I know, according to documents, the areas other than Omi including modern day Kusatsu where aobanagami was produced are Ise and Yamato. This is confirmed by documents from the Edo period. Further research is still needed to find out the background and factors behind the introduction of aobanagami in ukiyo-e.

I make talk return to the history of ukiyo-e. Nishiki-e was born about 1765, right after Mizue was born. This is a multicolor print with a much greater number of colors than before. Since then, this form of nishiki-e had become popular, and the representative works of Hokusai or Hiroshige, which you generally think of when you hear ukiyo-e, fall under this nishiki-e category. Since the age of nishiki-e, aobanagami comes to be commonly used as a pigment for coloring the blue parts of works. However, this is the case when focusing on the blue part.

The green color in ukiyo-e is usually created by mixing blue and yellow paints, but when focusing on the green part in that time, it seems that genuine indigo is often used as the blue paint. The reason for this is not clear at this stage. However, I think as my hypothesis that aobanagami was used because of the advantages of that is cheaper and its paint spreads better on the woodblock, but in order to produce a certain dark green color, the use of deep-colored genuine indigo would have been more economical and easier to adjust the green color.I hope to clarify also this someday in the future.

From about the latter half of the 1810s, the frequency of use of aobanagami, which had been used to color the blue parts, decreased, and the frequency of use of indigo came to increase instead. It is said that by the early 1820s, the transition from aobanagami to indigo was completed as the blue paint commonly used for blue parts. And after that, until prussian blue became popular, which was the next blue pigment, genuine indigo had been basically used for coloring the blue parts of the prints. In the background of this shift from aobanagami to indigo, I speculate that a new production method for indigo was developed and it became possible to supply it at a lower price than before.

Famous painters from the era when aobanagami was commonly used to color blue parts were Harunobu , Kiyonaga, Utamaro or Sharaku. It's also used for the blue part on the screen in the prints of about first half of the drawing period of Hokusai.

However, due to the characteristics of aobanagami, it is common that the color cannot be confirmed on the prints nowadays.

Aobanagami is said to turn gray, yellowish brown, or turn colorless over time. I don't know yet how it will change colors or fade under what conditions, but the part of aobanagami of the print I reproduced a few years ago is already turning gray though it was stored away from light, so I speculate that basically it's going from gray to colorless, and if the action of light is added in the process, it will turn yellowish brown. I would like to investigate those patterns of discoloration and their causes in the future.

There is a historical document about the aobanagami trade in the early 19th century, and it confirms that there were at least three quality ranks of the aobanagami on the market. In addition, aobanagami produced in Yamada villagein which was the center of production in the current Kusatsu area where aobanagami was thriving to be produced at that time, would have been known as a brand in particular at that same time (about 1800).

In other words, it is conceivable that various qualities of aobanagami were also used in ukiyo-e. This is also what I hope to clarify in more detail in the future.

Next, I talk about purple in ukiyo-e. In the nishiki-e era of ukiyo-e, started about 1765,, purple was basically made from a mixture of safflower red and aobanagami at least from the beginning of that era, and even after the aobanagami was no longer used as a single blue color in the prints after the first half of the 1820s, on the other hand, aobanagami continued to be used as a paint for purple until the end of the Edo period. So what is the reason for that ?: Why did aobanagami continue to be used for purple even after it was no longer used as a single blue color ?

There in recent years is one theory explaned sometime like that the people of the time would have an aesthetic sense of color, that is, they believed that the blue of aobanagami was necessary to express the purple of ukiyo-e, however, I consider that there is a more fundamental reason because the changes in ukiyo-e paints from the Edo period to the present day seem to be basically strongly related to the price of paints in each era or the ease of use in terms of woodblock printing techniques. I have a few hypotheses about that at the moment, so I hope to confirm them in the future.

In the stage of Meiji period, chemical dyes began to be used for purple, and aobanagami was no longer used in ukiyo-e after that.

The production of reproductions of ukiyo-e seems to begin from about 1890 in the traditional woodblock printmaking society. Historically, there have been various production policies for the reproductions, but basically it is a imitation print that is made by carving new woodblocks and using them to print newly in later years. However, in the history of reproductions, it seems that there is basically no attitude or idea to stick to use the original paints of the Edo period, such as aobanagami and other paints, and using aobanagami seems to have died out long ago in the traditional woodblock printmaking society.

That's not unheard of, but exceptional. As far as I know, it is said that there are some works used aobanagami in Enji Takamizawa's, who was active in the early 20th century , was a guy who originally restored damaged ukiyo-e prints and then started reproducing. And, Inuki Tachihara, who passed away in 2015 and was a woodblock print artist who had been reproducing by self-taught. Aobanagami is also used in his reproductions.

Therefore, in the history of reproducing, it seems that the people who have been particular about using aobanagami are different from the publishers, carvers, or printers who are the main producers of reproductions.

Basically, in reproducing by the traditional woodblock printer nowadays, many of the paints including aobanagami have been replaced by the use of chemical paints. There are generally cases that a reproducing which the color of aobanagami is printed in that looks like faded though its official opinion is like that it is a reproduction of the color of the Edo period printing. In the first place, there doesn't seem to be the high consciousness that trying to reproduce the original color of aobanagami in the traditional society of the reproducing.

From the points of view of the concept or the production policy that have been formed in the history of the reproducing, or the professional nature of the publisher, carver and printer, it seems that using or restoring of original paints including aobanagami would not have been basically important.

Nowadays , it is a common tendency in the reproducing that adding improvements or changes to the original print in order to make a reproduction more beautiful. Instead of such perceptions and concepts, reproducing by focusing more on restoration and working on restorative is to be still at present an effective means of recreating the original appearance in the Edo period of ukiyo-e prints . I think working on that will also lead to the resolution of various mysteries related to the paper and paints used in ukiyo-e prints in the Edo period, because that is naturally at the same time necessary to research those. In the case of aobanagami, that would be about when it was introduced into ukiyo-e, the background of its widespread use, the name and quality, the conditions for discoloration and fading, etc.

Among the producers of the reproduction, and also in general public, the color of the aobanagami in the reproduction doesn't seem to be a problem at all if it is printed by modern chemical paints and even in a faded yellowish brown or gray color.

In general, it seems that the use and restoration of the color of aobanagami is not necessary in reproducing ukiyo-e, but in my opinion, even if the exact same color can be produced by chemical paint, I want to be particular about using aobanagami.

I think that it is important to seek the same paints as in the Edo period and use them in reproducing in order to restore ukiyo-e prints, and also think that one person would appear once in several decades, who wants to know the facts such as what kinds of materials as paints and paper, tools, and techniques were used in actual to make ukiyo-e prints in the Edo period, rather than those of the the traditional woodblock print carver and printer nowadays, and wants to make the prints into reproductions that can be actually seen and touched. So I want to leave knowledge about those paints including aobanagami, and their manufacturing methods and handling methods as materials so that when such a person appears, it will be a guide for that person.

I feel that the essential meaning of my work lies just in that."

Previous article can be read in the following link,

1 note

·

View note

Text

I've posted an article about the history of ukiyo-e reproduction in my japanese blog. I did not create an English version this time due to the large amount of text and my busyness.

So, I put the link in the following.If you like, please translate it yourself and read it.

0 notes

Photo

Restorative Reproducing of Ukiyo-e Print, Taking the Example of Toyokuni Utagawa III, "Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido, Choemon Minakuchi".

(This article is a revision of a manuscript , that I submitted to a research journal but was rejected. Please read on the premise of verification deficiencies. )

I Introduction