Text

tfw you just wanna sit in a corner and read books on ancient civilizations but mum and dad wanna dress up for some spooky human tradition

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Mass Effect au where instead of the Starchild, Shepard finally gets indoctrinated by the Reapers at the very end and you have to play as the squadmate with highest relationship points or their LI to stop them.

If your ems is high enough, you can break through the indoctrination and bring Shepard back to stop the cycle.

If your ems is too low, you have to stop Shepard.

Permanently.

And it falls to you to activate the Crucible.

14K notes

·

View notes

Text

thankfully she can rely on her wife to take care of them 🌪️🎃

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

for personal reasons i need everyone to have seen this

267 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just a modern witch casting spells to bring out the spring with her gang, wearing moss coat and leather dress, in the remote woods near her small cottage full of herbs and spells.

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

portrait of Adèle to brighten up your day

#Adèle Haenel#poalof#portrait of a lady on fire#Portrait de la jeune fille en feu#P.28#it's her best outfit#don't fight me on this#my art

58 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hi! Was sketching today. Thought maybe you’d like to see this one :)

———————————————————————————————

aqsdfghjkgfd so you tell me this is supposed to be a “sketch” ?? are you for real 😭

It’s so so stunning !! thank you for sharing this designit, you made my day !

330 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Came back from my little break for that new article ! Here is the translation of Adèle and Aïssa’s interview for Libération. It’s a very long, but very interesting one. So i recommend to read it. There may be a lot of incoherencies so please tell me if something doesn’t make sense !

Aïssa Maïga and Adèle Haenel : «Finally there’s something political happening»

They stood up together at the César and have since been striving to invent a common front against all forms of discrimination. For “Libération”, actresses Adèle Haenel and Aïssa Maïga retrace the journey of generational awareness.

Some kind of symbol. A large mural, in tribute to George Floyd, a 46-year-old black American who died on 25 May when he was arrested by a white policeman, and to Adama Traoré, who died at the age of 24 on the floor of the “caserne de Persan” (Val-d'Oise) following an arrest in 2016, was painted at the beginning of the week on the façade of a building in the 10th arrondissement of Paris. Close by, the Adama Committee organized a press conference on Tuesday. Words, demands and the announcement of a new march to fight against police violence. It takes place this Saturday in the capital, from the Place de la République to the Place de l'Opéra. The organizers dream of seeing a huge crowd come together. This demonstration comes at the heart of a tense period. Young people are demanding answers and action, while many police officers feel that the Minister of the Interior is letting his troops down in the face of the scolding.

In the street, we will find associations, politicians and many people. Adèle Haenel and Aïssa Maïga will be there. Not a first. They were already present on June 2nd at the rally in front of the Paris high court. The actresses didn’t really know each other before the last César ceremony, marked by the speech of one and the shattering departure of the other. Since then, they have never left each other. Both describe the moment as a “turning point”. The fights converge.

When the idea of a cross-exchange came on the table to put words to their commitments, they did not hesitate. On Thursday, in a roadstead near Belleville, Adèle Haenel arrived first, followed by Aïssa Maïga. They are not of the same generation, the journeys and paths are different. The styles too. The one who got up at the announcement of the prize awarded to Polanski goes up and down, talks with her body. The one who, at the same ceremony, invited to count the black people in the room appears calmer, stays seated on her chair, speaks in a low voice. Adèle Haenel and Aïssa Maïga complement each other.

From where are you speaking?

Adèle Haenel: I speak from my personal political background, rooted in feminism, a background that is shaken by the worldwide movement around police violence and by the French movement around the Adama Committee. I would say that taking charge of my own history has given me the ability to deal with other broader issues that do not immediately affect me. I’m talking about a kind of political awakening. This desire to show my support for the families of the victims, for the political movement against racism and police violence in France, and for the actors who take a stand. I’m thinking of Omar Sy, Camélia Jordana and you, Aïssa.

Aïssa Maïga: This intersectional awakening evoked by Adèle is a place where I have been for a long time without necessarily being able to name it. For a long time, the racial question in cinema was so pervasive in my life that it cannibalized everything else. I felt that it was less difficult to be a woman, in a world that discriminates women, than it was to be a black woman. The work done by Afrofeminists in France and abroad put the words in my mouth that I didn’t have because I didn’t have that heritage. I am speaking from a place that is on the move and that is not made up of certainties, that is made of interrogations, especially about the fact that I can implement changes on my own scale. And I’m also speaking from a place that is purely civic and is tinged with various influences. I didn’t grow up in a poor suburb, I didn’t live in financial precariousness, I come from a rather intellectual middle class, it gave me certain tools, and yet I haven’t escaped this very French thing, a soft racism, rarely seen but which is haunting… because it’s omnipresent.

Why did you get involved with the Adama Committee?

A.M.: Because this is a fight for justice. It was Assa Traoré who came to meet me during the release of the collective book Noire n'est pas mon métier (“Black is not my job”). I knew her from afar, I knew her struggle, and she appeared. The support became obvious and it has really taken shape in the last few months. I was immediately impressed by this woman, her quiet strength, and this ability to forge a bond, to think of her family drama in political terms. Her voice matters. She’s not just an icon: she allows a movement to emerge.

A.H.: For me, it’s even more recent, I had to go through a problem that was going through me, that involved my body in discrimination in order to mingle with other injustices. I was listening to what Assa Traoré was saying and I was struck by her determination and intelligence. But it is only very recently that I also became physically aware that I could not fail to support this woman and the whole fight against police violence and racism, in the same way that I am taking up the fight for feminism and against sexual violence. I can’t have it two-tiered.

On June 2nd, more than 20,000 people gathered in front of the High Court of Paris, at the request of the Adama Committee. An unprecedented turnout, with many young people, why?

A.M.: The Adama Committee saw very well the link between George Floyd’s drama and their own. The death of Adama Traoré, choked under three gendarmes, was materialized before our eyes with the unbearable images of Floyd’s death. The French youth who look at these images cannot fail to make the connection, it is obvious. There is also a form of accessible activism that is developing via social networks. Activists will involve others through simple, accessible sentences: if you are not a POC, you are still involved, it is your responsibility to listen and take an active part, at your level, in the fight for equality. There is also the idea that we need to establish a link between police violence, the racism that can be found in other social spaces, the issue of gender equality, the environment, and the urgency of dealing with these problems now. There is also a form of anxiety among young people: they are told that in fifty years’ time there will be no more water. And finally the feeling of injustice, which is omnipresent and linked to the circulation of images on social networks. Police violence follows one after the other, and this creates an accumulation effect. It is not just a dogmatic political vision, but a reality that is lived or perceived as real.

A.H.: There is a turning point in the effectiveness of the movement as well. This feeling carried by Assa Traoré that we are powerful. It’s not just ideas that go around the world, it’s ideas that make the world happen. It gives hope and responsibility to a whole generation.

During Aïssa’s speech at the Césars, in which she confronts the profession with the near-invisibility of actors, filmmakers and producers from French overseas territories and African and Asian immigrants in French cinema, you are in the room, Adèle. You don’t know each other yet. Do you understand her speech immediately?

A.H.: It’s obvious, but it’s not immediate, it takes a little time to understand the extent of the racist mechanism when you, yourself, haven’t been forced to see how it works. I was brought back to particular assignments, but not to this one. So it takes a long time before it becomes unbearable evidence. When Aïssa takes the floor, it’s courageous because the room is very cold and it’s making it even colder. I thought it was funny and I thought “finally, something political is happening”.

Did you both understand that people find it violent to count black people in the room, and even that they might find it paradoxical to split the audience?

A.M.: Counting isn’t splitting, it’s measuring the gap between us and equality. When it comes to inequality, to be blind to color is to be blind to the social burdens that come from our history and the imagination that flows from it. I am fighting for art and culture to deconstruct racial fictions. In our field, cinema, there is a tendency to believe that when a few exceptions appear, the problem of racial discrimination is solved. I do not think that my presence, that of Omar Sy, Ladj Ly or Frédéric Chau, Leïla Bekhti, for example, however gifted they may be, exonerates French cinema from an examination of conscience. There is always an over-representation of people perceived as non-white in roles with negative connotations - and it’s not me saying this, it’s the CSA, through its diversity barometer. There are still too few opportunities for younger people, who today in 2020 deplore what I deplored when I was starting out. Still too few non-whites behind the camera and almost no one in decision-making positions. I started this job when I was 20 years old. I am 45. A generation, not a few exceptions, should have risen. It hasn’t. And it’s unbearable as a citizen, a mother and an artist.

At the César ceremony, I deliberately used a inflammable symbol. If we refuse to measure differences in access to opportunities in terms of racial discrimination, perhaps we are accepting the status quo. Today, we need concrete action by decision-makers and numerical targets in order to measure progress. A few personal successes, however brilliant they may be, cannot justify the violence of large-scale unequal treatment.

A.H.: The substance of what Aïssa said to the César is relevant, it speaks to the moment, and being shocking has the virtue of awakening. The criticisms that followed were “I agree but”… In fact, it means that even when the substance is right, the form is never the right one. It’s a form of censorship, there are people who have the right to speak and others who don’t.

A.M.: Allowing oneself to express anger head-on is taboo because we are actresses and we are supposed to preserve the desire that others project on us. And also because it highlights the precarious nature of this profession: are you able to overcome your fear, to express your opinion, with the risk of losing something?

A.H.: From my point of view, that of a white woman - forgive me for putting myself in this position, but it’s still unfortunately an assignment - I see that when I spoke about what happened to me personally, I received a lot of support, especially from people who are not especially on our side. However, as soon as I spoke up, politically, to say that giving the prize to a rapist fleeing from justice was an insult, all of a sudden I was really overstepping what I was entitled to do, what I could interfere in…

Do you think there’s a “white privilege”?

A.M.: Words are so tricky…

A.H.: When Virginie Despentes uses the term “white privilege”, it’s a bit related to Aïssa’s gesture when she counts the black people in the room. It’s a question of pointing out, by calling up words that should be those of the past, the gap between the evolution of universalist ideals and the facts of manifest exclusion at work. Provocation points out this flaw and invites us to close it.

Is there state racism?

A.M.: I don’t know about “state” racism, it would have to be written into the laws to say that. The right word is systemic: it means that there is something that does not allow for real equality, something in the established rules that allows a small number of people to discriminate without being worried. What also raises the question is the inertia of the state in the face of the continuation of systemic inequalities.

From what you say, we are at a turning point in the struggle against racial, gender, social and other forms of discrimination…

A.M.: I felt the turning point in 2018 with #MeToo, Time’s Up, and when I saw all these women from such diverse backgrounds (in the streets) after Trump’s election. It was an image I had never seen before in my generation. It was in the United States, and yet something happened to me in France, because I had been dreaming of this convergence for a long time. I’m not here to defend my chapel. I’m not going to be satisfied with a breakthrough if blacks have more roles while Arabs and Asians are still in a degraded situation in French cinema. The convergence I’m talking about didn’t quite take place at the time of #MeToo, which quickly became a white women’s movement in my eyes. In French cinema, there is also the “50-50 for 2020” movement [collective for parity and inclusion founded in 2018, editor’s note] that I saw coming like the guerrilla movement we had been waiting for for a long time, pragmatic, quick, positively impatient, very constructive. The work done in favor of parity is colossal. On the other hand, I regret that diversity is the next program. But it cannot be the next program for me, that is the mistake. I’ve talked about it very openly, and frankly in a fairly relaxed way with some of them.

A.H.: Much more relaxed than I was, by the way!

A.M.: And then I said to myself that the battles are progressing on different levels and that we’re going to have to find some kind of alignment. The fight for women’s rights is not just a women’s issue, it’s a men’s issue, just as the fight against racism is not just about POC. And it wasn’t until 2020 and the murder of George Floyd that there were those voices, especially white voices, that said, “This is my problem too.” Including in France, where this awakening of consciousness is made possible by the work done by the families of victims of police violence.

A.H.: In my political journey so far, I had forgotten to understand the places where I am not just in a situation of domination. I am also, as a white woman who is not in a precarious position, in a dominant position in certain aspects. Understanding that, feeling that, is essential. My political agenda was focused on feminism, and I didn’t realize that it was implicitly white feminism, unintentionally excluding. What Aïssa says seems fundamental to me: the agenda that would order one cause after another is not conceivable and leads to inertia. It leagues us against each other in identity issues that are sterile, since they reiterate the terms of oppression. This is a major issue in the effectiveness of political struggles: how can we mobilize without reiterating the categorization we are fighting against? This implies understanding that there is a deep articulation between all systems of domination and that there is a need to defend these causes in a cross-cutting manner.

Aïssa’s speech on June 2nd, during the demonstration initiated by the Adama Committee, called for a fair, dignified and positive representation of minorities in the media. But who can judge what is dignified and fair? Only the ones who are affected ?

A.H.: Today, in France, female characters in films are implicitly white women: I have a much wider range of possible jobs than that offered to a black actress. But in my field of so-called universal women, very often, women are offered satellite roles around male characters. These roles take up what is considered to be the normal white female nature, of restraint and reification. What appears natural here is a cultural construction of identity that is done precisely through stories. This is one of the reasons why the political stakes of representations in the cinema are so important.

Is this a criterion for assessing or rejecting a work? What should be done with existing works that have been reassessed as problematic?

A.H.: Works must be recontextualized. They are not created out of nowhere, out of time. Let’s question them! That doesn’t mean that we stop watching them, but that we ask ourselves what their political substratum is and what they convey. Questioning representations is a sign of vitality. And that does not mean that we would no longer have the right to see these works.

A.M.: With this waltz of statues of slavery figures in the United States or in the French overseas departments at the moment, the citizens gives their answer. Either the work must be contextualized, in a museum or in a place with a historical explanatory note, or it must stand out.

Is it women, more willingly than men, who carry this convergence of fights ?

A.M.: I feel a change in the scale of our lives, a major turning point in the way we perceive each other and allow ourselves to hybridize in these battles. Regarding the massive presence of women from cinema in front of the High Court on June 2, I wonder. In particular about my own capacity to build bridges… while guaranteeing the visibility of the fights against discrimination against women or POC. How do we ensure that the fight against discrimination, for equality and equity, is as visible as the rest? I am not at all sure how to do this. But it has to be done. When, the day after the César, I received a text message from Adèle, even though we don’t know each other, and she writes to me to say “I heard you. I’m here. Let’s meet”, it can be as simple as that.

Why did you send that text?

A.H.: Because of the solitude in this room. And the brave gesture of saying what she said on stage. We’d met the same evening and maybe I hadn’t caught the moment, I was captivated by our own event… That is, what had happened after we’d, let’s say…, gone to get our coats a bit earlier in the dressing room… (Aïssa Maïga laughs) And I thought, let’s not forget the constructed gesture, the political intentionality of Aïssa in there. I wanted to get closer to her courage. So I think that we shouldn’t talk about masculinity by saying “men”, that we should consider masculinity as a field of organization of power with its own complexities, and its intersectional repercussions. I refer to Angela Davis’ book, Women, Race & Class, on the issue of the difficult articulation between the civil rights movement in the United States and the emerging white feminist movements where there was a lot of racism. Why don’t we think of ourselves as spontaneous and necessary allies between categories of discrimination, racial, social and gendered? We need to take the history of this division seriously in order to work on it and overcome it. As Assa Traoré does in an ultra-intelligent way when she says “Whatever your religion, your sexual orientation, wherever you come from, whatever your skin color”. It is an invitation to self-criticism of our own movement. This is my discovery at the beginning of this year: the self-criticism of my history as a white feminist.

When you get up during the César, is it thoughtful or impulsive?

A.H.: This award was a claim to the right to do whatever you want as long as you are at the top. That is to say: rich white men who don’t feel concerned when we talk about violence. What it means beyond sexual violence is that there are people to whom repressive laws do not apply. It’s as if the police and the laws shouldn’t act against them, but around them… And that’s what you feel in that moment in the room. What happened on César night was a dissolution of the status quo. Now it’s either you stay in the room or you don’t stay in the room.

A.M.: And it was important to be there at the César, because I read a lot about boycotting that evening, but for me there was no question of backing out. A boycott is not just staying at home behind your television, not being there without anyone really noticing. It was important to say that the home of cinema is also our home, our space, our place of expression. We are in a position to speak out and for that to have the virtue of provoking discussion. When that person wins that award, it’s the time of the turkey, where someone praises the rapist grandfather, when everyone knows. And you’re breathless, you can’t move, time becomes elastic, everything is extremely heavy, it’s unreal. You enter another dimension. And the fact that a person manages to regain possession of time, to become master of their time and master of their body by standing up and saying no, it put oxygen back in, it woke us up. Adèle and I looked at each other two or three times during the evening, we knew we were together. There was something like a physical experience. We boarded the ship together.

We’re spotting the allies.

A.M.: That’s right. And time returned to normal when Adèle, Céline Sciamma and others, including me, got up. It was a coherent political gesture in which many people recognized themselves.

Do you think that your political positions, formalized at the César, can have an impact on your career?

A.M.: The question is how do you break a family secret? Festen is one of my favorite films. (Laughs) I wasn’t born at the time of the 2020 César, it’s the result of a personal journey and a legacy. Others before me have spoken, for example Luc Saint-Eloy and Calixthe Beyala on the same issues at the Césars in 2000. When Canal + and the César invited me to come and give an award, I said “yes, but I want complete freedom”. Blowing up a family secret is a movement for self-liberation, it’s an essential meeting with yourself. Choosing to be on the side of silence, of the status quo and therefore of injustices with full knowledge of the facts is something I was quite incapable of doing. The consequences for one’s profession are not that one doesn’t care, but spitting out what one has to say is a top priority. The question of what it is going to cost behind it is resolved by the feeling of freeing the word, provoking debate, making a generational contribution to the fight for equality, which in essence concerns us all. I have an appointment with myself around 60, 65, the age when my children will be about the same age as I am today. There is something about transmission. I want to be able to look at myself in the mirror. I don’t want to tell myself that I haven’t taken advantage of my little privilege of being a POC exception in French cinema to the detriment of all those young people I meet on the street, who aren’t white and who say to me with fear in their stomachs, “Do you think I can still do this job?”

What about you, Adèle?

A.H.: The message that was sent to me very clearly by a casting director is that I will never work again. Obviously, this person was very sure of himself, since he wrote it in print capital letters about a dozen times. What do you say when you ask for respect and silence? They say, “Don’t speak out politically because it’s not your role”. But also: “Don’t take the lead artistically either because you’re an actress, you have to follow the genius of your director”. This whole structure is part of this culture where you shouldn’t listen to yourself but to submit. I don’t know what the consequences will be for my job. What is certain is that I will never regret it. We did something that night that freed the voices of a lot of people. That is worth much more than all the threats to my career, which in any case is always fragile, because it is a precarious environment. If I totally respected the rules and said, “Yes, yes, you have to separate the man from the artist”, that wouldn’t stop me from being able to get out of the game. It’s as much about inventing one’s life as trying to open up the future.

Written by Cécile Daumas , Rachid Laïreche and Sandra Onana. Photo by Lucile Boiron

947 notes

·

View notes

Photo

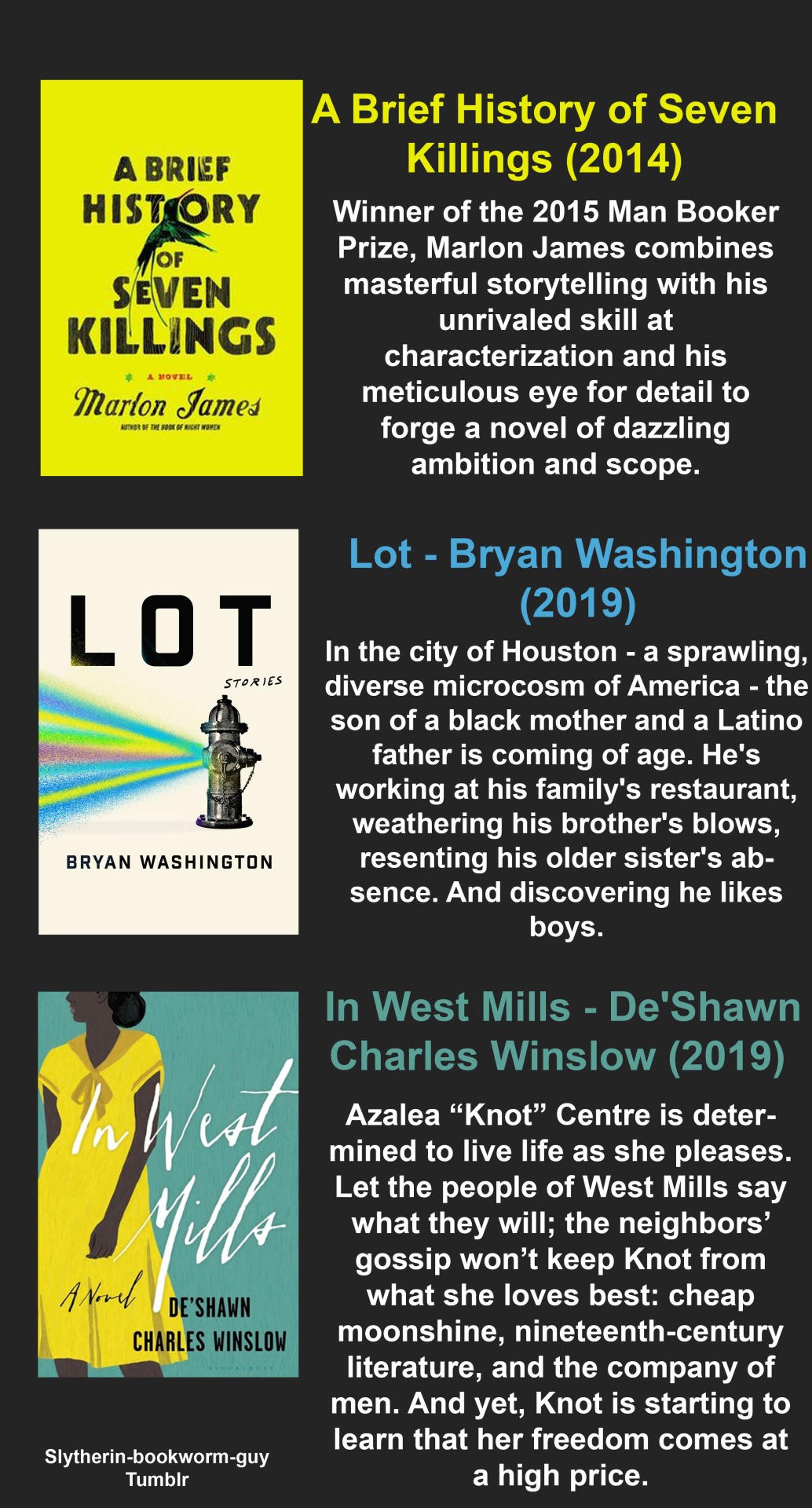

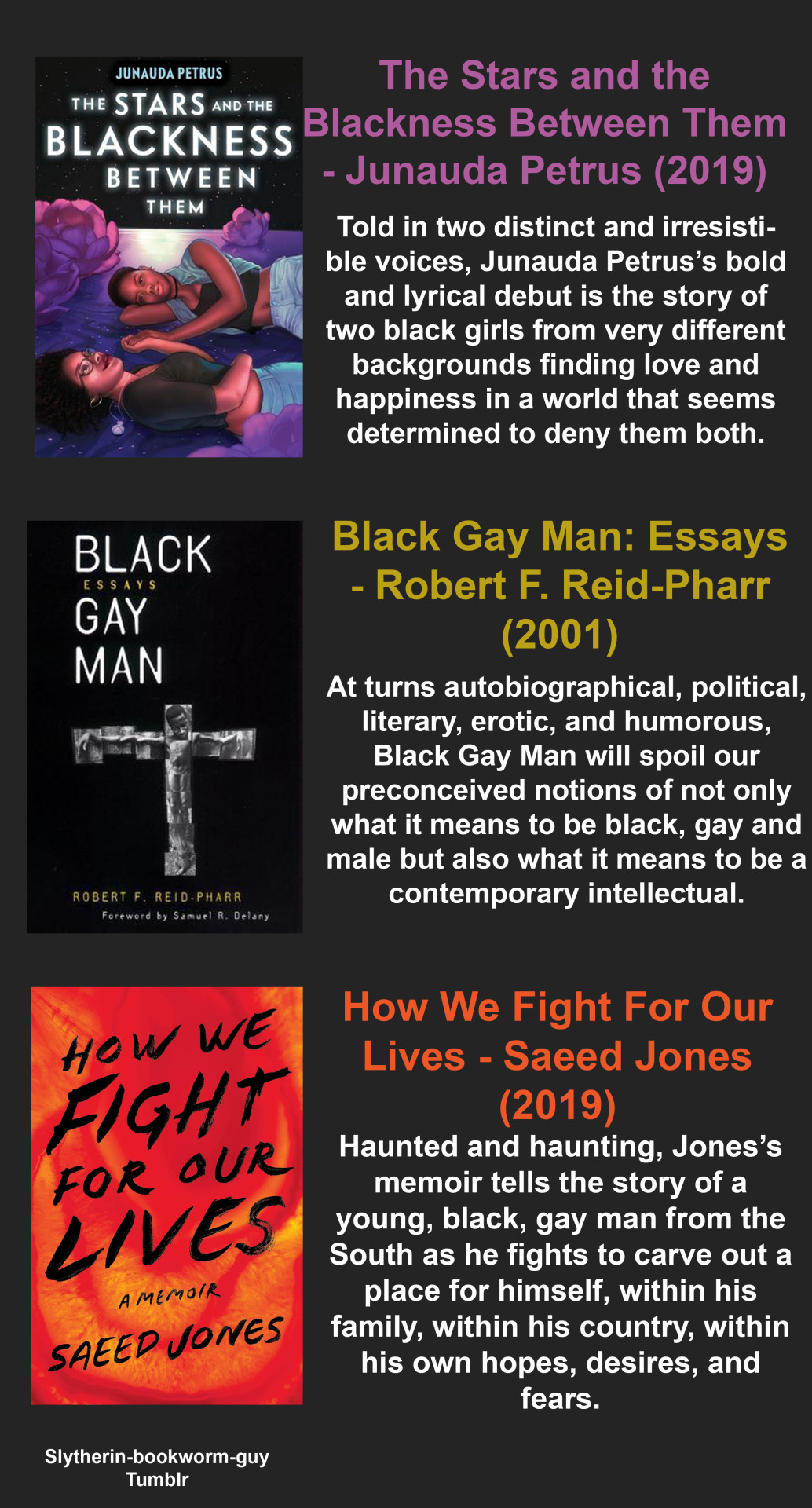

24 LGBT+ Books by Black Authors

I’m seeing a lot of the same books on my dash, so I spent a few hours researching some lesser-known books. These books fall across a variety of genres and age group.

Ways you can help

37K notes

·

View notes

Text

HOW TO DONATE TO BLM WHEN YOU HAVE NO MONEY

a black woman named zoe amira posted a video on youtube. this video is an hour long and filled with art and music from black creators. it has a ton of ads, and in result will rack up a ton of revenue. 100% of the ad revenue from the video will be dispersed between various blm organizations, including bail-out funds for protesters. it will be split between the following, dependent on necessity

brooklyn bail fund

minnesota freedom fund

atlanta action network

columbus freedom fund

louisville community bail fund

chicago bond

black visions collective

richmond community bail fund

the bail project inc

nw com bail fund

philadelphia bail fund

the korchhinski-parquet family gofundme

george floyd’s family gofundme

blacklivesmatter.com

reclaim the block

aclu

turn off your adblocker and put the video on repeat. do not skip ads. let it play on loop whether you’re listening or not. mute the tab if you need to focus elsewhere. but let. it. play.

youtube will donate to blm for you.

youtube

please, please reblog. for people who don’t have money to spare, this is incredibly important information to have.

265K notes

·

View notes