An Introspective blog seeking to illuminate inspiration, growth, love, and beauty in the everyday journey.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Silence on the Brink of Extinction

“Seek out a tree, and let it teach you stillness” –Eckhart Tolle

I recently heard a poignant statement that “silence is an endangered species”. This declaration from Gordan Hempton, an acoustic ecologist, enthralled me. The idea that silence could be endangered was an entirely new perspective on modern life. And though this terminal prognosis may be questionable, it’s quite evident that the noise of our human population is only growing worse and has thoroughly overrun nature in favour of progress. In fact, the deliberate and intentional experience of silence is virtually absent and definitely antiquated in the vast majority of societal living. There is no doubt that we humans fill our lives with sound. We are continually plugged in to phones, tvs, radios, music, arguments, advertisements, and information. We are inundated. And though I’m fortunate to live near some wonderful natural places to escape the discordant racket of civilization, many are not as lucky, as the earth’s last wild and serene soundscapes are becoming fewer and fewer.

So, off to the woods I went. It’s amazing what you can hear in the natural world when you take the time to stop…and just listen. Several types of birds twittered around me in sporadic harmony. The river gushed and whooshed, leaves rustled above. How effortlessly nature can stun us into stillness— the rhythm and music of it, a quiet lullaby of sorts. A dog’s bark, the light whirl of wind. My own steady breath. And beyond all these things, the vast and beautiful chasm of silence—the peace of a mind temporarily without thought.

In my twenties I studied meditation at a Buddhist centre in Colorado. My week there is now a blurry memory of sitting painfully still for uncomfortable hours on end whilst beating myself up for the inability to train my wandering mind. I later learned that the goal isn’t to stop thoughts entirely. This is impossible. Instead, it is to create more space between thoughts, to allow thoughts to pass, and in the pausing, to sink into our own inner peace, a peace that thrives and pulsates in the present moment. Contrary to sitting meditation, some have found this peace and presence unwittingly whilst in a state of motion. Activities such as running, mountain biking, or sky diving, for example, can unconsciously plunk us into the present moment, as they call for a clear head and steady attention. And the pleasure we derive from these acts is not only physical, but is also psychological, and through escaping the mind, can be truly transformational.

Silence is certainly endangered. Most humans fear it. And like any other entity that is strange and threatening, we try to kill it rather than understand it. I am the first to admit that silence has often unnerved me. The practiced ease in which I can fill a lull in conversation has been born out of my own wrangled value that silence is to be eradicated and avoided. Yet I’m hoping to correct that. I’m striving to change my thoughts on the matter, and in fact, to pause my thinking as often as possible. As it turns out, our ever-turning mind and its propensity for relentless thought is the root of many forms of anxiety. This is because our minds are very seldom dealing with what is directly in front of us. Instead, we are often mired in the past or looking towards the future, one reality having already passed, and the other not yet even conceived. We are often grasping at intangible and illusory states of being. It’s no wonder that our minds spin round and round these uncontrollable events without a safe resting place. How much of my life have I spent wasting time and energy on a past I can’t change and a future I can’t control? And now I could waste more time worrying about that time wasted, or instead, I can sit here in the present moment, with my warm cup of tea, and these words as I type each…one…out…individually, and I can listen to the hum of the dishwasher and my giggling children upstairs and know that in this precise moment, this singular second in time, I am alive and I am content.

It's taken me decades to cultivate this awareness, that admittedly graces me less frequently than I’d prefer. Perhaps if I was raised in India or Thailand, the tools to cultivate inner quietude would be laid out before me as simply as my children’s bedtime routine. And, as I find value in my children’s growth and well-being enough to teach them how to brush their teeth, solve math problems, and resolve arguments, shouldn’t I also be equipping them with some tools for alleviating anxiety, for making space for peace and presence?

So off to the woods we went. And for a minute, I asked them to be quiet and listen to the sounds around them, to pause their chatter and truly listen. Eliana closed her eyes real tight and cocked her face to the sky and Elijah laughed. Even at their impressionable ages, embracing silence is a strange and new experience. It’ll take practice, but with time, perhaps they will come to seek that silence on their own, and instead of fearing it, they will trust it, knowing that it has the power to illuminate clearer pathways through their own minds.

0 notes

Text

UNTIL I LEAVE THIS WORLD

I wrote the following piece a couple of years ago, before the pandemic, having great hesitation to share it, as so many people avoid discussions about death and dying. To be clear, I'm talking about death in broad strokes here. Of course death due to severe illness or trauma is terribly upsetting. I mean more the inevitability of our own deaths. For reasons unknown--reasons that might reveal themselves in the future--I have always been fascinated by the reality of our passing from this world. It's a truth that we all must confront, but few care to look at it until they are forced to. I prefer to face it with eyes wide open, in the hopes that the awareness of life's fragility will bring more meaning, awe, and fullness to my time on this earth...

Fifteen years ago, I was buried alive. This is not a metaphor. I was living in Flagstaff, Arizona then, a nexus for the alternative, and stumbled upon an eccentric group in the desert who held watch while people dug their own graves and slept within them. Their idea was, if you could comprehend your own mortality, you could overcome all fear in order to live a meaningful life. I was invited by Ayana, a woman I secretly feared to be a witch; her sparkling blue eyes and mischievous smile scared and allured me in equal parts. Though the idea of being buried unnerved me, I had already begun to search for a deeper understanding of death, (a subject most individuals gladly avoided) and I couldn’t easily refuse the opportunity.

At the time, my experience with death was fragile. I’d recently lost my 57-year-old father to heart failure, and the devastating inevitability of life’s passing had become a visceral reality. My own future demise, however, was an illusion I had trouble imagining. I was still young and ignorant. I hadn’t yet met my husband or birthed my children. I hadn’t formed these intrinsic connections that death could easily threaten to strip from me. I hadn’t yet discovered the wrinkles—the daily aches and pains—that the body taunts us in reminder of its expiration. My understanding of the world was simply smaller.

‘Just come along’, Ayana said. ‘You haven’t lived until you’ve pretended to die’. I was understandably anxious about sleeping underground. I dreaded a surge of claustrophobia would rise within me and I’d be shouting for them to let me out. I imagined the bugs and the worms I would have to befriend. Yet there I was, standing awkwardly with a group of strangers, discussing which burial plot would be mine. And then, before I could protest, I lowered myself into the dirt, letting them slide the thick board over me. I could see the very last pink sliver of the setting sun and my mind held tight to its soft glow before all was black. Above me, the board shuttered as someone shovelled dirt upon it in rhythmic thuds.

I don’t remember ever smelling dirt before that day. It was only when it surrounded me, that the smell became overwhelming—fragrant and sharp all at once. Feeling around me, my arms couldn’t extend without touching its sticky wetness. What creatures had I disturbed in excavating this hole? I prayed they wouldn’t find their way into my clothes while I slept. The darkness was complete and the immobility stark. It was a maddening sensation and I ached to stretch and run. The luxuries of movement would have to wait. So, abandoning my body, I retreated inward for solace.

We weren’t offered any guidance for reflection while lying in our graves. Perhaps our guides knew the questions and answers would be personal to us all. My life’s events came back to me in short bursts as I drifted towards sleep. My family, my travels, relationships and worries all found me there. I dreamt of my father—the same reoccurring dream I’d had since he died. In my dreams, he was still alive. And I accepted this reality in the dreamworld, watching him move about as normal, until suddenly he would evaporate into mist, leaving me with the weight of his absence. That night, in the midst of a dream, I called out for my dad and saw the shape of his face form out of the clouds. I woke in the hard dirt, with an unbearable bladder, and fought to remove my bottoms enough to edge the puddle to one side. Feeling more animal than human, I steadily awaited release from my cage, the night a whirl of darkness and confinement.

Eventually, the dawn erupted, and I heard the board being lifted from above me. I carefully climbed up out of the dirt and stretched my arms into the sky, my muscles singing in relief for movement. The desert was alive with colour, the cacti standing tall and proud in the glow of the sun. I could feel Ayana’s gaze, her eyes full of questions. I wouldn’t share with her any epiphanies from my dark night, just the gentle reminder of the wonder of living. My dad will never again watch a sunrise, eat chocolate, hug his family, or let music fill him. Life is not an expectation, but a treasure. And now, in the company of my children, I appreciate this truth more than ever, as my kids’ growth mirrors my own ageing in the unforgiving crawl of time.

I had forgotten about my burial experience until recently when I was walking the dogs on a footpath that runs alongside the cemetery. The rain was pouring down heavily, and I passed an old man who exchanged a weather-weary sigh with me. He stopped then, and called out, pointing to the graves, ‘Darling!', he called out. 'At least we’re not on that side of the fence. We can be grateful of that!’ His words made me smile, pricking me with the reminder of death’s great wisdom. If we let it, death will remove its shadowy cloak to reveal a wise and constant teacher, whose lessons are those of gratitude, fearlessness and love, while there is still time to learn them.

1 note

·

View note

Text

To My Husband, Eleven Years On

These four thousand days

Of hearts intertwined

We buried our roots

in the other’s earth.

Oh, the blessed dirt,

the spilling of sweat,

the trading of cells

tucked snugly under nail.

I remember the fog

Of sleepless nights before you.

Until, like solid oak,

You unfurled your arms

to offer every gift

a tree has to bear.

And home you became,

both the walls and the air.

So now on your trunk

let us carve out our names,

and make from your bark

a map for our children.

As they too, one day

will be longing to root.

And knowing our tale,

may they find a home in love.

0 notes

Text

The Wisdom of Water

Today I walked alongside a river, and it spoke. Of course, it didn’t gurgle or spit words as I know them, but still, it had much to share. I watched it carefully, flowing steadily forward without looking back. I witnessed it dodge branches and climb over stones, and change course to avoid passing hurdles. It never complained about these surprising obstacles. I stood in marvel and it gently reminded me that it is born to flow, to take the shape of whatever it falls into. It is fearless and simple, and unafraid of change or loss. It accepts the path, wherever it leads, and trusts that time will unfold better seasons.

We are not as far removed from the nature of a river as we may think. Human beings, of course, are composed of great quantities of water. A new-born baby can be made of up to 75% water, while most adults are between 50-60 percent. The source of life itself is swirling within us, and in difficult times, it might be helpful to remember that, aided by the very nature of our watery structure, we have the muscle memory to flow and adapt with intuitive ease.

Many years ago I read a New York Times bestselling book called “The Hidden Messages in Water” by alternative Japanese researcher, Masaru Emoto. He was a pioneer in the study of water molecules, arguing that water is highly sensitive to human words, thoughts and sounds. He gathered this information through taking photographs of frozen water crystals before and after exposure to opposing stimuli. He found that when water was exposed to kind words, prayer, and soothing music, its molecular structure completely shifted in positive and spectacular ways to create beautiful patterns. And in the presence of unpleasant sounds, fears, or harsh negativity, these water molecules became disfigured, disconnected, or ugly in appearance. The photos of these crystals are breath-taking. Emoto’s research may not have been wholly endorsed by the scientific world, but his discovery that water could potentially have some form of consciousness is profound. And why shouldn’t it? Water is at the very core of our human physical foundation, with our brains and hearts alone composed of over 70% of this fascinating elixir, and we humans are unique in our ability to exercise conscious intelligence. What could this mean for us, taking into account all of this water within us? And how is our molecular structure affected, given the daily positive and negative impressions we are subject to? And furthermore, what is that voice inside us saying—that internal voice that’s completely inaudible to others, but often our loudest and most influential critic. Is it a voice of disapproval or one of encouragement? How we treat ourselves and others is a matter of great importance.

Like water, we have the ability to shift and evolve. We are malleable. We are not fixed beings. We can be like the river. We know how to flow. We have the vitality of water within us and we can call upon those properties when we need them most. Already, we have adapted greatly in life, and we will continue to. Human beings are simultaneously completely ordinary and utterly magical. As is water. The sheer fact that we are able to exist on this uncoincidentally water-covered Earth at all, is amazing. Thank you river, for sharing your wisdom.

#thisunfoldinglife#growth#lifeinspiration#reflectionsonlife#water#personalnarrative#loveandkindess#personalwriting

1 note

·

View note

Text

THE OAK TREE

The oak tree extends its long arms

up and out into space.

curious if beyond that great void

there are other trees too,

reaching with tips of branches

to grasp at knowing.

She longs to climb

into the sky's sweet embrace

where wind will cool,

sun will warm

and rain will wash away doubt.

And under nights whisper

she'll wonder again

upon each echo of the owl,

what mysteries

are just out of reach.

.

.

.

.

.

#thisunfoldinglife #growth #lifeinspiration #reflectionsonlife #meaningoflife #prosewriting #transatlanticwriting #personalnarrative #memoir #loveandkindness #ageing #cycleoflife #personalwriting #expat #enisehutchinson #poetry

0 notes

Text

We see life not as IT is, but as WE are: A vote for Optimism

A long-lost friend recently proclaimed me an optimist. Hmmm. Yes. I am, with little exception, an eternal optimist. In some poetic cosmic joke, I came into the world on April Fool’s Day. Like most youngsters, I was endearingly wet behind the ears, but in addition, I had a predilection towards gullibility that gave my birthday deeper meaning. I was the Naïve Nancy who could be easily conned into believing anything, simply for my sheer want to see the goodness in everyone. My compass for authenticity was faulty and immature and I believed such tall tales as 12-year-old local heart-throb Danny Jones wanting to kiss me, and my neighbour’s declaration that Michael Jackson came to his house for dinner. These foibles often resulted in dramatic shame—my pale little face quickly enflamed in the scarlet badge of embarrassment. Anyone else might have draped a protective cloak of cynicism around them, but for me, the weight of it never felt quite right. So, instead, I gathered enough wisdom to better measure and scrutinise life’s oppositions, and an optimist I remained.

Yet I must whisper this truth. The critics, cynics, and naysayers may have fingers poised in wagging disapproval. Positivity, I’m afraid, can sometimes be mistaken for weakness and ignorance. Some may think I have suffered no hardships. I can assure you I have. I have been to those dark places of anguish where everything is ugly and aching. Yet rather than sinking amid the storm, I’ve had to fight to become steadfast and buoyant. Rather than replaying the past like a heavy soundtrack to my life, I sought to choose a different tune. And I do believe it is a choice. Make no mistake, choosing to retain hope in the face of adversity is not an act of weakness. It can often be a measure of great strength.

Deaf and blind American author Helen Keller once said, “Optimism is the faith that leads to achievement. Nothing can be done without hope and confidence.” Keller, who at the tender age of 19 months old lost both her hearing and sight from an unknown illness, learned to forge her way through deadening darkness to thrive against all odds. Before she could even develop the vocabulary of a toddler, the ability to communicate her inner world was debilitated. Keller didn’t even know that words existed until the age of seven, when a teacher traced the letters w-a-t-e-r on her one hand, while running cold water on her other. Through great perseverance, she went on to become a prolific writer and political activist, as well as the first deaf-blind person to earn a Bachelor’s Degree. I gravitate to stories like these. Helen’s story could have been one of pain and anguish, a wallowing embittered soul with reason to blame and reject life itself. She chose differently. We all have this choice. Some fortunate souls instinctively lean towards hope, like stepping from shade into sunlight. Others need to consciously choose it again and again, knowing that in the choosing, they are shifting their very reality.

I once heard someone utter some extraordinary words, and I’ve never viewed the world the same again: We see life not as IT is, but as WE are. There’s a statement worthy of careful reflection. What a revolutionary concept! Life is not objective. It is subjective. And we, the perceivers, are a massive element in the orchestration of how our life unfolds. Our individual perspective and how we view the world around us, can literally affect the experiences we have. We are the lens and the filter through which our whole life is interpreted. We are the observers and the storytellers, and life responds to us based on our perceptions—our past and present, our tender worries, our fears and our dreams. All of these filters colour our outlook and, in turn, help to define our reality. If we anticipate struggle, it will find us. If we seek out kindness, it will surround us. The weighty truth of perspective becomes evident when a singular shared event can throw one person into despair and another into growth. These concepts, once thought to be the subject matter of only the spiritually inclined, are now finding their way into many fields. Even the entrepreneur knows that his own self-belief and the perception of his abilities, can either limit or expand his reality and consequent success.

The world will continually give us justification for worry and cause for anger. On a daily basis, it will throw us a dozen problems. Many of us can instantly name a handful of reasons why life, at the moment, is particularly hard. But how would clinging to these complaints serve us. Coddling our negativity may only thwart forward progress. Our mind will happily chew upon whatever fears, worries, and annoyances we place upon its plate. If we are what we eat, surely then, we are what we think. And now, with the current state of the world, our thoughts can circle more than ever like hungry vultures inside, ready to feast on any source of weakness within us. We can let our worries consume us, or we can learn to transform our thoughts into food we can actually use. There are thoughts that energise us and fuel us on our journey, and there are thoughts that will leave us sick and heavy. We, alone, are the caretakers of our heads and our hearts. A negative mind left alone to run rampant will be forever looking for difficulties. The brain, after all, is a problem-solving instrument. Perhaps it’s wise to guard our perspective, and wherever possible, let our minds rest upon trust and hope. We think our cynicism can protect us, but sometimes it is only a barrier to inner peace. Call me a fool, but I quite prefer being an optimist.

#positivity #finding hope #optimism #lifeissubjective

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Balance of Society is the Job of an Entire Community (or How I Became a Dog Walker)

Since the pandemic has rendered me temporarily unemployed, I’ve been thinking a lot about work. I imagine many of us in lockdown have begun to ponder our working lives. And if not, perhaps we should, considering our jobs take up nearly half of our waking hours. For some, this break from the workplace will shed valuable light on how much our jobs actually serve us, speaking not only financially, but physically and emotionally. Some will lose their jobs altogether. They will lose the businesses they’ve grown, and whatever positions they have worked tirelessly to achieve. For some, it will unlock new pathways to once-forgotten enterprises, interests and pursuits, while others may be forced to compromise their ideals for the necessary exchange of food and shelter. This virus has remarkably turned everything on its head. The solicitor has been declared unnecessary, while the supermarket cashier has never been more highly regarded for her service and perseverance. We have been urged to re-evaluate how essential our roles are, to not only us individually, but to society as a whole.

This extra time for contemplation may have a beneficial outcome for us all. Western society, in particular, is prime for a period of self-reflection and scrutiny. We are a judgmental lot and have become terribly fond of equating a person’s character with that of their job or career, as evidenced by the question we’ve all asked and answered more times than we can count: “What do you do?” The correct response is not: “I dance, hike, travel, garden”. The expected answer is “I’m a doctor, cashier, teacher, waiter” etc. This response is then followed by the enquirer’s practiced nod of recognition—that singular moment in which we are instantaneously categorised and defined. We are put in a box with many other doctors and cashiers, regardless of our portfolio of masterful oil paintings at home or our well-stamped passport. Now, the doctor, who has followed in the footsteps of his father, may swell with pride in sharing his esteemed rank. Yet what about less celebrated employees, like the window cleaner, or the road sweeper—how might they feel about being evaluated entirely on how they earn their living wage? As we are beginning to witness, there is great value in both the barista who whips up our coffee and the barber who cuts our hair. Perhaps we have forgotten that maintaining a society's balance is the job of an entire community.

Many years ago, I was quite happy to be defined by my job. After finishing college with a master’s degree in English Literature, I braved a move to New York City to begin a professional career in publishing. And in response to the all-important question, “What do you do?”, I was able to answer in a clear steady voice, “I’m an Assistant Editor at Random House Publishing in Times Square”. Granted, I was not a doctor, but where I came from, it was a career impressive enough to raise a few eyebrows. For a 22-year-old, I had an amazing salary, an apartment of my own, and I was always delighted to answer the big question upon meeting new friends and acquaintances.

Soon, however, the city began to wear on me. New York can bewilder and disarm a person of any character, and I didn’t belong there. I tried to camouflage myself within my surroundings, but I was a deer in a world of hunters. I felt attacked by the vapid superficialities of the corporate world and the hordes of people pressing upon me on streets and subways. I resented the necessity of carrying pepper spray when coming home late, and the constant clatter of a city always in motion. I found fleeting comfort in smoking cigarettes, drinking margaritas, and watching copious amounts of cable television. In an effort towards better health, I went for a jog, and from out of a car window, someone catapulted a raw egg at me. Flabbergasted, I stood at my kitchen sink, cleaning the yolk from my hair and cursing the city. I glanced at my fridge. I had placed a post card there a year ago, and now it was staring back at me. It was an image of Mexican Hat Rock —a stunning natural red rock formation that depicted a man in a sombrero. I had camped underneath that stone man on one magical trip to the Southwestern States and it was a marvel that he was still there along that lonely road in Southern Utah. I closed my eyes and dreamed myself in that wild patch of land, to hear the rushing of rivers over traffic, and to see that sheet of blue sky unmarred by glass and steel.

The promise of a different world beckoned. My life needed reinvention. I packed my Toyota Corolla, counted my savings, and set my compass westward. The path I had chosen was clearly not working out, and so I swerved, and in doing so, the road unveiled new frontiers. I didn’t know where I would land or what I would do when I got there, I just needed to go. It was perhaps my bravest moment. It marked the beginning of choosing freedom over fear, and I trusted my heart to steer the journey. Weeks later, I landed 2,300 miles away in Flagstaff, Arizona. In direct opposition to the nine to five rat-race, I filled my CV with an eclectic list of jobs including waitress, care-giver, receptionist, pet-sitter, office cleaner, jewellery designer, teacher, cashier, para-legal, and Grand Canyon tour guide. I began answering the big question with more accurate details: “I hike, write, play guitar, paint.” I spent my free time outside under the sun and found friends to share in the beauty of places like Mexican Hat.

Years later, I became a full-time mother, which granted me the most important job I’ll ever have. And as my babies grew, I started to panic about what to do next. I set my sights on returning to University for a degree in Counselling, yet I first needed to earn the money for tuition. While brainstorming funding possibilities with a friend, she suggested I become a dog walker. Her idea was a cosmic lightbulb and I put my full energy into creating a dog walking business. It’s funny how life never fails to surprise. What began as a means to fund an entirely different pursuit, soon became an entity of its own—a successful enterprise and a pleasure. I found peace and tranquillity in the outdoors, loyal companions in the dogs, and the freedom and independence of running my own business. Instead of being in locked in an office, I am out in the fresh air, roaming fields and forests with my dogs. Serendipity helped me carve out a path of my own, and I haven’t thought about counselling since. I am perfectly content exactly where I stand. There are some who can’t help but diminish what I do. When I answer their enquiries about my occupation, their expression belies a perceptible criticism or disapproval. Yet, I don’t take offense. After all, being a dog walker is what I do, not who I am. Instead, I secretly smile inside, knowing that in some great twist of fate, I’ve found a perfect profession that keeps me healthy, happy and balanced. I haven’t seen my dogs now in over seven weeks and I miss them immensely. If there was any part of me that took my job for granted, lockdown has abolished it. Being a counsellor would have saved me from picking my kids up at the school gate covered in muddy paws prints, but my mental stress and inner quietude surely would have been at risk. Some people will never question the work they do. For me, it has always been a matter for great reflection. And so, for my little role in this community, I am extraordinarily thankful.

0 notes

Text

In the Darkest of Places, There Will Always Be Light: The Pandemic as Food for Thought

I used to love food shopping. I am a foodie, and shopping for groceries, like ogling restaurant menus, is a feast for the eyes and mind. Six weeks ago (before the apocalypse) my weekly shop was a pleasant, leisurely, almost creative affair. I happily left the kids at home and had no list or agenda, so I meandered through the aisles thinking simple thoughts. “Hmmm, I might try stuffed peppers for a change. Ooh, yes, I’ll get some chopped beef for the slow cooker.” I casually picked things up off the shelves, touched all sides of the trolley with wild abandon, and even stopped to hug a friend after a casual chat, before I carried on thinking about curry sauces and risotto, and animal shaped biscuits for the kids. It feels like a dream now in the wake of today’s shopping expedition—a challenging exercise in mental stamina and a gross display of social awkwardness. After waiting in line for thirty minutes with my husband’s old dust mask and make-shift rubber gloves, I was finally granted permission to enter the store. There would be no wandering, not with the systematically laid out arrows to follow. I had to stick to the path and the list. Toilet roll, bread, milk, eggs, wine. Only the essentials. I carefully wove around people, avoiding contact and conversation, my eyes glued to the list, and aimed to leave the store as quickly as possible. Then, the disinfection stage…car keys, door handles, food packaging, hands. What should have been an easy task took nearly three hours. I never thought I’d say it, but I hate shopping. Yet I will adapt, as I have, to everything during this crisis. As we all must. It’s remarkable how incredibly malleable we are as a human species. Though the road ahead will be longer and more arduous than any of us can imagine, we will adapt. And perhaps, dare I say, we may even flourish.

This pandemic is asking a lot from us. We are staring mortality right in the eyes and some of us have never before given it much thought. We are grounded at home, missing our friends and wider family, our haunts and activities, and are restricted in nearly every imaginable way. Our lives have been stripped back to utter simplicity and the purest of things are rising in stock. Fresh air has rarely been praised by so many mouths. Matters we once took for granted hold new pleasure and purpose: our daily dog walk, our bench in the back yard or garden, quality time with our families, reading and hobbies. Never before has the foundation of our very existence been called into question. Who are we? What are we doing here? In the absence of our usual noise, distractions, routines, and desires, we are given a mirror to reflect upon what truly serves our lives, and what derails it. What gives us balance and what brings us stress? If used wisely, this time could unveil a road map of new avenues for thought and action. What dormant parts of our minds and hearts might we find, what hidden doors to our creativity. What dreams have we placed high on the shelf, that are now begging for attention. Looking back on our lives, far less catastrophic events have catapulted our growth.

There is a quiet hum at the moment, while we all process this mess. Some of us are unfortunately too trampled by sorrow for reflection. They have lost loved ones to this terrible virus. Some are too mired at the front lines to pause for thought—they are our dear soldiers during this war. Some of us are too sad and shocked and unwilling to shift. But there are many of us who are having pure moments of discovery and insight, and are in turn, bestowing the world with positivity. I’ve never been more in awe of my fellow humans. Even in the darkest of places, there will always be light. The dark could not exist without relative opposition, and light bulbs are switching on everywhere. People are volunteering their time and efforts, fulfilling roles beyond imaging. They are singing and writing, performing and sharing, inventing, and launching new ideas and enterprises. They are creating in great swirls of energy and motion and inspiring others to follow their own breadcrumbs to passion and delight. People are bestowing great messages of love and hope, laughter and friendship, and necessary levity and comic relief. People are caring for their communities; they are supporting their elders and cobbling the ability to teach their young. I don’t know where I will be at the end of this pandemic, but something is brewing deep within me. This fiercely strange, scary and unusual time has great lessons to teach. My goals will shift and dreams reshape, and one day I will begin sentences with, “If not for the pandemic, I wouldn’t have….”

I will undoubtably not be the same person at the end of this.

I believe, we are all seeds waiting in the dirt for the storm to pass, eager to poke our little heads out of the earth to take in a big breath of sky and let that new sun shape us into taller, stronger, and more vibrant beings. And if the storm returns to cut us at the stem, we will rest for awhile and grow again. For that is what we do. Without any will of our own, our hearts beat without prompting. We grow and age whether we choose to stand still or move forward. In every hardship there is a lesson, and it is up to us individually to discover what this time is trying to teach us. It is up to us whether we close ourselves in fear or we muster the courage and hope to open our hearts enough to bloom.

0 notes

Text

Choosing Love Over Fear: The Transformation of the World

In December of 2012, the world was supposed to come to an end. The Mayans, who were a significantly advanced culture that collapsed in 900 A.D., left us their calendar which cryptically ended its 5,126-year-long cycle in 2012. Many believed that their calendar end was an apocalyptic prediction and a host of doomsday information infiltrated the web and media; some believed it would be a time for large scale transformation and rebirth. I was pregnant with my daughter for the majority of 2012 and I too worried about these shadowy forecasts. Of course the world didn't come to its conclusion then. It’s laughable those innocent fears now, based on almost nothing, when we are all staring a world-wide pandemic in the face.

Friday, I couldn’t stop crying. The thought of not hugging my friends, seeing my relatives, losing my business, watching people die and economies crash was just too overwhelming. The fears kept hitting me in giant tidal waves, knocking me down to drown in despair. I spoke with a friend who described the feeling as being in mourning. And like all those who experience loss, we agreed that relief comes from acceptance rather than resistance. But like a toddler, I wanted to throw a tantrum, and scream that someone’s taken away my teddy, my security blanket! The virus certainly woke the selfish beast in me when confronted with the realities of assuring survival. It's ignited negative behaviour everywhere, leaving people in a panic to fight over food and supplies, among other things. Like frightened children, we've been left alone, waiting for someone to scoop us up and relieve us of all this fear! This invisible criminal has left us feeling small, weak, and shamefully humbled.

But there are many who have chosen to choose love over fear. In the last week, we have witnessed millions of people coming together to support one another in profound and majestic ways. The outpourings of hope and comradery, the offerings of help, and the positivity even, the levity, is becoming contagious. We haven’t seen the worst of this pandemic, but hopefully we will see the best of humankind.

2020 may see humans symbolically embracing each other on such an unprecedented vast global scale. Perhaps the divisions between country and race can crumble enough to tear down walls we never thought we could demolish. Our care for each other is boundless. And our strength at this time is a collective force that is building with each individual rising up and surrendering to love rather than to fear.

And what does fear provide us with anyway? It immobilises us. It deceives us. It selfishly favours individuals over communities. When the panic finds its way into our beings, let us overcome it through gratitude. Let us eradicate it by singing all the things we are grateful for. If this virus has given us anything useful at all, it is the remembrance of what is truly important in this life. Virtues like connection, love, generosity, and empathy, are rising in value above anything material.

I am devastated by the people this pandemic has taken in death. I’m angry that it’s separating us from our loved ones, and systematically removing our freedom of will and motion. But we must be stronger than our sadness and anger, and choose love and hope whenever we begin to despair. The world as we know it is in transformation, but perhaps it is not an ending. It could very well be a beginning. People are shifting everywhere. People are connecting in magical ways, sharing and building, and exploring new directions. They are embracing valuable time with their families, reconnecting with drifted friends, spending time in nature and re-evaluating what nourishes their very existence. I’ve never been more impressed and awestruck by my fellow human beings. We are all passengers on an awakened global trajectory with a truly unknown destination. Where we land after this mess, is a scary thought. But I know in my heart, the new world can hold much more love and kindness than the old one. And so I’ll keep choosing love and gratitude over fear. And, as a friend, a sister, a mother, and a human, I’ll send out love to my global family in a way I never have before.

0 notes

Text

Gratitude Over Guilt (or How I Ended Up in the Doghouse)

Winter is hard in England. It goads the complaints out of us recklessly. Our sun, that golden sphere of warmth and hope, has disappeared in a shroud of cloud. The land is soggy and pulls us down before it holds us up, and the illusory promise of a brighter tomorrow teases but doesn’t deliver. Life’s monotonous routines feel more draining than ever in these greyer shades of day. And though I may be more optimistic than some, I’m not immune to the heaviness of the season. It’s a restless time, a time that raises internal questions that erupt erratically from within me. And this is how I ended up in the doghouse, when I declared to my husband: “I’m going to move into the woods or become a monk!”

We had just finished watching a film about famine in Malawi, an African country we had both travelled to a decade ago. The shocking reminder of such poverty sat painfully within me. How dare I complain about the absence of wine and chocolate in the kitchen, or how badly our bathroom needs renovation—I had just watched a barren African village nearly starve to death from drought! I hadn't yet worked out how I would look after my young children in the forest, or if I was even allowed to be a monk, particularly a married one, but my impromptu proclamation was, in hindsight, a cry for perspective. My sweet husband doesn't often take my spontaneous assertions seriously, but I could tell from his face that I'd offended him. “Don’t you enjoy this life that you’ve created with us?” I assured him that I do, but my discomfort was inflamed. Surely, I can't live peacefully when there are suffering people everywhere?

And there is suffering everywhere. People just like us are victims of starvation, war, drugs, poverty, disease, homelessness, and suicide. And others are chained to their fears, money, greed, sadness and anger. These realities only touch me on a small scale in my tiny village in rural England. My experience is largely the life I've actively worked to nurture—a life blessed with a beautiful family, a steady job, and a comfortable home. Yet how can I go about my little life with all this struggle in the world?

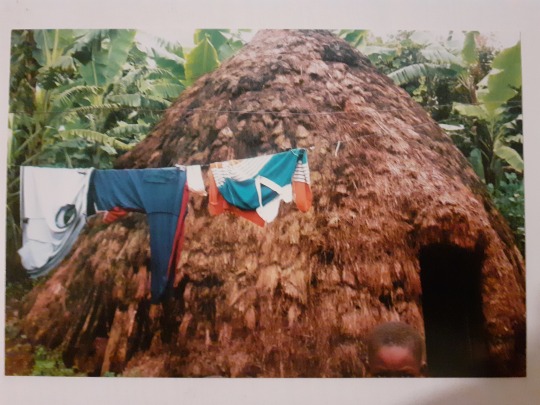

My thoughts return to 2011, when my husband and I backpacked (in our pre-children days) across Africa through Kenya, Tanzania and Malawi. It was a trip we had each craved well before our paths aligned. Africa dug its fists into our chests and ripped out whatever foolish illusions we had of the world. We witnessed entire families living out of straw huts, scarcity of food and water, and kids fighting for their education, walking several miles to a school with rudimentary facilities. We had a relatively simple life back home in The States, sharing a small one-bedroom apartment without cars, mobile phones or expensive possessions, but in Africa we were the utterly wealthy.

Along our travels, we took a ferry to Zanzibar, an island off the coast of Tanzania. The ferry was filled with local commuters, stuffed together in a heady swirl of heat. They carried nervous chickens and livestock, fresh fish and goods back and forth to the island. The women hauled large bundles upon their heads and the men dragged heavy carts loaded high above their sweat drenched faces. We hired a guide there named Rama to take us snorkelling. Rama was lovely. He was a true islander—a muscled mid-forties seaman in flip-flops and shorts. I remember innocently asking him: “Have you ever travelled outside of Tanzania?” He shook his head firmly, “No, of course not”. His answer jolted me. Of course not. I was immediately embarrassed by my question. Indeed, travel itself is a luxury. What disposable income might he have for travel. How could he justify such a selfish undertaking when his wages surely were needed for family, home and food.

Rama was part fish and dove straight down fifty feet to the bottom of the ocean without mask or fins to return moments later to report on the creatures beneath. At one point, he emerged from the water with a massive shell the size of a bowling ball. A slimy sea creature glistened from inside its intricate folds. He proudly presented it to us—a gift. We didn’t quite know what to do with it and declined, saying he could keep it himself. Rama beamed. “Thank you”, he said, holding the shell up with two hands, “tonight I make this into soup”.

Africa pulled from deep within us our guilt, fear, awe and gratitude, leaving us humbled and awake. We thought we’d never forget its lessons. Yet, like many Westerners amid our surroundings, it’s dangerously easy to become blissfully ignorant. Many of us are granted freedom from worry over the quality and abundance of our water, the nutritional value and variety of our food, and the safety of our homes. Our thoughts can rest more pleasantly on dinner plans for Saturday night, or our upcoming holiday. And though guilt can find us in these realisations, perhaps gratitude is a more effective emotion.

And so, Gratitude finds me now. And, as if I were the reverent monk, I repeat a little chant: “Thank you. Thank you. Thank you for all this before me”. And when I go upstairs tonight, to kiss my sleeping children, I'll thank God that they're resting safe and warm in a prosperous country. And I'll look into my dear husband's eyes and share our hopes for the future, knowing we have the ability to dream bigger than simple food and shelter. And I'll tell him that I'm not going anywhere, except further into gratitude.

0 notes

Text

Wonder: A Fountain of Youth For The Mind

My kids love to ask fabulous questions. Daily, I’m enlisted to field queries in a range of subjects from physics to technology and religion to science, and my children are only five and seven! Their first enquiries were quite simple, so their “all-knowing” mother had a quick response to nearly every one. But as my inquisitive children have grown, my ego has shrunk, and been swallowed and digested on repeat, as I’m forced to respond: “well kids, I just don’t know…let’s ask Google.” And though inventions like Google may be one of the culprits in my ever-decreasing knowledge bank, as all this touch-ready information discourages our brains from retaining information (like my husband’s phone number—the same one he’s had for the last nine years), our immediate access to information can open great windows to the mind.

Last year, on our relaxing sunny family holiday, my little girl asked me, “Mum, I wonder, how far away is the sun and the moon?” We were basking lazily on beach towels near the sea, and I gave her the best guess I could muster. Later that night, however, as the moon stared down at me, my daughter’s question beckoned, and I went online. I’ve never had a scientific brain, nor do I typically spend more than a few minutes scouting for the answer to any question, yet there on holiday, with an abundance of free time and a relaxed constitution, I quickly got absorbed in my research. Like a ravenous explorer, I spent several hours consumed in the study of light years and astronomical units, carefully mapping out the distance between earth and its celestial neighbours in order to some way wrap my mortal brain around it. I wish I could share my now forgotten findings, but know this…I was struck. I stepped outside underneath that blanket of sky and the awe of it all, the magic of this beautiful earth, that houses my small being, amongst a million other beings, on a great expanse of land, beside a bounty of water, floating in a sea of sky, of stars, and suns and moons, all existing in harmony, made me spin in wonder. And I thanked my kids for reminding me that all this is Wonderful.

I believe children are here to help us rekindle our wonder—our sheer awe and curiosity. Through their eyes, we can experience once again the magic and excitement of our first taste of lightening and rainbows, of sunsets and falling snow. In our adult drive to fluff our feathers and prove our abilities, we forget what happiness can lie in humility. In a state of wonder, there is little room for ego, for right and wrong, and rules and restrictions; we are given permission to be still and open, to enjoy the freedom and flexibility of thought. This is fertile ground for growth. And the benefits of growth shouldn’t be solely restricted to the young. Though our adult bodies have reached their physical maturity, our hearts and minds, like those of children, still have room to flourish. Engaging in curiosity and awe for the world around us can open the door to possibility and a pathway to imagination. It can bring forth answers to life’s most inspiring questions and can deliver us from complacency. The sheer joy of wonder is a fountain of youth for the mind.

Curious if anyone else had come to similar conclusions, I, once again, went online and stumbled upon something called the “Science of Awe”. Scientists and psychologists have recently begun to study the unique emotion of awe and the body’s physiological responses to it, and the benefits of awe are astounding. Not only can it grant us more happiness and better health, but it can inspire a higher drive towards communal sharing and caring, and help align us more peacefully within the present moment. Perhaps increasing our exposure to life’s vast and mysterious offerings will benefit us more than we ever thought. I still can’t remember exactly how far away the moon is, or how many light years it would take to find the sun, yet I can tell you the magnitude of such a thought, is alone, enough to pause my mind. Opportunities for awe are abounding. We don’t need to wait for thunderstorms or fireworks. If we simply step outside and be still, the sun, trees, and passing clouds, will whisper to us their secrets. The longer we can rest there in open wonder, the more potent the elixir.

0 notes

Text

I Refuse To Be A Prisoner Of Fear

My five-year-old son recently asked me, “Mum, what’s your biggest fear?” Well…my own ageing, your health, the loss of my family, and living a mediocre life all sprung to mind as responses, but considering his age, I smiled and simply replied: “wasps”. I didn’t have to ask him what his biggest fear was. He’d been waking several nights in a row with a newfound fear of the dark. I could remember how palpable my own fear of the dark was as a child, and how I’d slowly come to terms with it. Living alone in the woods certainly helped towards this end. How simple now were his placid childhood fears. The years were waiting to magnify them to far more threatening proportions.

Fear touches us all. Some of us have no idea how truly powerful its hold upon us is, yet our very happiness depends on how diligently we guard ourselves against it, how earnestly we control it. Of course, we can’t ditch fear altogether; it has saved us from being trampled by cars when crossing the road, and has protected our babies from harm, yet it is not to be wholly trusted. Fear can be a spy and a criminal, an imposter who professes friendship in order to mask its deceit. It needs to be kept close and monitored, examined and probed, for the more we succumb to it, the more it will enchant us, promising safety at the expense of our own freedom. And, if we’re not vigilant, fear will surreptitiously erect its walls around us, imprisoning us in tall towers of our own unwitting construction. It is then, that it will grin deviously, pretending to protect us, while it is truly the warden of our cells.

Somewhere along the line, I said no. Actually, I shouted it: “NO!!!!!!” Remarkably, I discovered that every time I accepted bravery’s invitation, my little foe grew weaker, smaller, and more manageable with the light of truth upon it. I sought out human examples of bravery wherever I could, those fierce and courageous souls out there who refuse to let fear limit their path. They are the ones who move through life dodging fear’s bullets, accepting challenge, embracing growth, and overcoming worry. Their mere self-belief drives their success and life rewards them for their flexibility and resilience.

Brazilian writer, Paulo Coelho, is just one of these souls. After reading his book “The Pilgrimage”, in which he embarked on a 500-mile Spanish pilgrimage route that’s existed since the Middle Ages, I too wanted to go. Fear was delighted to offer a dozen reasons as to why I shouldn’t go to Spain. Fear’s argument: “You have no money! You will be alone. It is unsafe, irresponsible. What job will you return to? Won’t you be lonely? You can’t possibly walk every day for miles. This is foolish! You aren’t brave enough or strong enough. You aren’t one of those people who does incredible things”. I let Fear list all its worries and reasons, and after the onslaught, there remained a little voice inside me that said, “yes I am”. I knew I had to go. Embarking on the pilgrimage became a personal challenge to combat fear. I didn’t realise it at the time, but my decision to go would reshape my whole belief system around fear. I would tackle my worries surrounding scarcity, loneliness and strength, and ultimately gain the faith that I too was deserving of a remarkable and extraordinary existence. Having learned this, I am now better equipped to pass on these values to my children.

Our truths, our whispered hopes and dreams, ceaselessly follow us around, begging to be realised. Life has much more to offer us than worried stagnancy. Time will ignorantly press on, with the passing of each sun and moon, to etch deeper lines into our flesh—a visible road map of the joys and heartaches of our journey. And death will find us inevitably. Yet how we live before then, is our gift. Fear would have us frozen in position with each new sunrise—the same thoughts and anxieties trapping us day after day. Yet when the sun rises again, let it find us wiser, stronger, and diving further into our fears, rather than running from them. With every act of fortitude, we take a hammer to Fear’s walls, enough to reveal that big beautiful world that’s eagerly waiting for us to embrace it. The more we do what scares us, the bigger and braver we become, and life will, in turn, bestow onto us all the happiness and fulfilment we could ever dream of.

0 notes

Text

The Quest for Evidence of the Divine

When I was a little girl, I used to beg God for proof of his existence. Faith wasn’t enough. I needed solid undeniable evidence. “Dear God, if you exist, could you make the lights flicker?” Pause. “Dear God, can I hear you whisper?” Pause. “Dear God, can you make me pretty and brave and worthy of love?” Through the ages, my requests matured and the intervals between them lengthened, but I always privately prayed for some true sign of his or her presence in my world.

There was talk of God all around me. Over a decade of Catholic schooling impressed upon me the need for some supreme being to inform my journey. Catholicism, however, with its fire-and-brimstone instruction, can be a scary beast. It took many years to undo the fear of hell I’d imagined would result from my placid childhood sins. So, when I was 18, I left the Church to embark on an intense twelve-year search for spiritual meaning. I divorced religion, yet I still sought relationship with the divine, knowing its face and name would shift and change with my discoveries. I began with literature—looking to writers like Emerson and Whitman to show me the imprint of God in nature. I sought out psychics and reiki masters, seeking answers in energy fields. I studied manifestation, the principles of attracting and creating one’s own reality. I retreated to the mountains of Arizona to experience the psychedelic effects of the SAN Pedro cactus, meant to induce introspection and healing. I travelled to Northern Colorado to study at a Buddhist meditation centre, and I went to Spain to walk the 500-mile Camino De Santiago trail. For forty days, I walked alone, in pursuit of truth and inspiration, a pathway to myself and a higher power. I read every book I could get my hands on and talked about spirituality with whomever would listen. Eventually, to leave no stone unturned, I even revisited my old friend Jesus. I was a woman on a mission—a spiritual detective.

My quest was further fuelled when I heard other people’s stories—candid accounts of the divine dwelling just beyond our eyes and ears. One such story was shared by a dear friend of mine, who had a mystical experience while visiting the small town of Lourdes in France. Lourdes is home to a holy grotto where a fourteen-year-old peasant girl claimed she once saw the Virgin Mary. Now each year millions of pilgrims come to Lourdes to ask for healing from its presumably miraculous waters. My friend visited the grotto in the dead of winter, in the stillness of night, and from out of the darkness, appeared the bright twinkling of blue lights all around her. She described the grotto in its beautiful blue glow and reported that, even after, at random moments, the twinkling lights return to envelop her. When she revealed her experience, I was desperate to see this blue light appear out of nothingness. She was a witness to the supernal. She had her proof that the world we see before us has mysterious layers of which we cannot even perceive. Where was my proof? I didn’t know it at the time, but I was never meant to experience those lights. That was her gift—her confirmation. And I would find mine.

Though the bulk of my exploration hadn’t yet granted me empirical verification of the Divine, it left me with an open heart and a reverence for the magical orchestration of life. I was 31 and my journey had taken me into the depths of myself. I knew who I was. I was happy within myself, and though I didn’t have all the answers, the ones I did have all pointed to love. I think in the end, the simplest and most powerful truths rest in love’s hands.

And then one night, I had a dream—a dream so vivid, I can still visualise it eleven years later. I dreamed I was flying, soaring in the air over Zaire, an African country to which I’ve never been. Typically, in my dreams I take flight by slowly extending my arms out from my sides and pushing the air down beneath me until it lifts me off the ground, just above the trees. This time, I was wearing a harness of a sort, and I was aware that I’d humbled myself enough to accept the support. When I landed, I heard the gentle voice of a man behind me. He spoke: “You did very well. I’m proud of you.” I couldn’t see his face, but I could very clearly hear his distinctive British accent. “Come with me,” he said. “We’re going on a journey.” He gave me a small card and on it were the initials: “G.H.” I stared at the card and said out loud: “This is the man I am going to marry.” I looked up then and the room was filled with large colourful spheres of light. I smiled in appreciation, while children danced happily in front of the man, obscuring his face beyond recognition. Then I woke. I immediately wrote down every detail of my dream, carefully underlining the shocking specifics of this British man with the initials G.H. who I was supposed to marry?!

At the time, I was working reception at The Grand Canyon Youth Hostel in Arizona, so the likelihood of bumping into a few Brits was a possibility, so I kept my eyes open. For two weeks, I scoured the hostel in expectation. And when G.H. didn’t appear, I let it go. Perhaps it was just a dream. And then, a week later, on Thanksgiving Day, I somehow caught the attention of a British traveller at the hostel. He was eager to engage, but I wasn’t interested. This guy, with his Beatles haircut and happy grin, wasn’t like the depressed lumberjacks I typically went for. His interest was keen however, and after I rebuffed a few of his invitations, he said, “Come on—You give me a chance and I promise it’ll end up in marriage.” I laughed and he left the reception area. I was taken aback by his confidence, wondering what normal man speaks of marriage with someone he hardly knows? All of a sudden, my dream came back to me. I’d forgotten about the mysterious man with the British accent. I quickly checked the guest registry, searching for his name, and there in front of me were the words: Garry Hutchinson. G.H.

I waited for him to return, my heart in my chest. And when he did, we sat together, and I told him of my dream. The words tumbled out of me, swirling around us, and he smiled, “I suppose you should to give me a chance now?” We fell in love rapidly, diving deeply into one another, our hearts fusing into an entirely new organ. It was clear from the beginning that our partnership would only magnify and multiply our happiness and individual growth. It’s funny how I couldn’t see that when I first saw him. The dream was my compass. Some mystical force of goodness brought me direction, knowing I wouldn’t recognise love if it stood right before me.

Now, after nearly ten years of marriage, I sometimes take for granted the marvellous circumstances that brought Garry and I together. But when I do remember, I’m grateful for my shiny nugget of proof that there are sacred, intangible, and divine forces amongst us. I don’t talk about God much anymore. God, after-all, is a word with a thousand meanings on a thousand tongues. Instead, I love with great depth and length. And in seeking love, and its sisters—kindness, empathy, generosity—I can see evidence of the divine in everything. My church is now any place where bliss can find me—a leisurely bike ride at dusk, lying beneath leafy trees, dancing with my husband, and reading bedtime stories to my children, feeling the pleasant weight of their little heads upon my shoulders. And with my kids, in their marvelling at rainbows, fresh snow, and starry skies, I’m continually reminded that it’s a truly magical world.

#lifeanddeath#meaningoflife#whatarewedoinghere#introspectivewriting#thisunfoldinglifeblog#howifoundmysoulmate#findinglove#magicoflife#spirituality

0 notes

Text

The Stories We Leave Behind

We have a little bedtime tradition in our house called “story in the head”. This practice has been invented by my inquisitive son Elijah. After the picture books, when he’s snuggled beneath blankets under the breath of “good nights”, he asks for one last story in the head. Upon his first requests, we made up quick tales about his favourite subjects: super-heroes and ninja battles. But soon, Elijah wished to hear real stories about us—what we did when we were children—what he was like as a baby. “Tell me a story in the head”, he’d say, “about when you were a little girl”. I’d share with him how I came to be adopted when I was an infant, about the zip-line my brothers and I made out in the woods behind our house, and how I broke my nose with a tennis racket at fifteen. At first, I struggled to pull up my memories. Yet with some careful prodding, I found that, one by one, strange little snippets of moments, to life changing prepubescent events, came flooding back into recollection. His questions were often thoughtful and perceptive. “Before I was born, did you know you had a boy in your belly?” and “Did you want to have only two children?” His husky little five-year-old voice would continue, “And, mummy, is your daddy now in Heaven?” Elijah, we soon discovered, has a true affinity for history. He is now our family record keeper, and delights in recounting his parents’ pre-child backpacking adventures in Africa and our wedding day when that February snowstorm almost buried our wedding chapel.

I am a record keeper too. When I received my first journal at ten, my love of pen and paper was sealed, and I documented everything. Even at an early age, I understood the alchemy of harnessing my history—my swirling thoughts and feelings—to capture them safely onto paper. Writing was my release, and letting the words spill candidly onto the page provided an objective lens for my life’s joys and struggles.

This practice was well in place when my father died of heart failure before I turned thirty. I purged my sadness onto paper and wrote tirelessly for months until there were no more tears or words. But where were my father’s words? In his death, he took with him hundreds of stories that would never again be told. Unlike my son, I didn’t think to ask my dad who he was before I was born. I should have probed him about his own father dying when he was a teenager, about his panic of being drafted into the Vietnam War. I could have used his insights on property and his thoughts on parenting. What were his greatest fears and happiest triumphs?

The harsh finality of his passing left us with a void, scrambling to share stories and hold onto memories. His death exposed my delusions about the graciousness of time, and suddenly, life was infused with a sense of urgency. My thoughts began to rest on my birth mother, the stranger who grew me inside her. So, with my mother’s blessing, I began my search for the once eighteen-year-old woman who was too young to keep me. She was a sprawling blank page, and my child-like imagination envisioned us kindred spirits who would share our love for travel, art, and psychology. I craved connection and eagerly waited for word of her whereabouts.

Several months later, I received a letter from the adoption agency. I stared for ages unblinking at the cold black words: Birth Mother Deceased. Devoid of any tact or reassurance, it declared unequivocally that I was too late. I found an address for her sister, and in our correspondence, I discovered that my mother battled mental illness and throat cancer to die of a heart attack at the age of forty. Of the photos I saw of her, few captured her smile. There are images I wish I could now forget—the frail skinny woman with missing teeth—the scarf tied conspicuously around her neck to conceal a tracheotomy. I was twenty-two years old when she died. Happily consumed with graduate school and planning a move to New York City, I thought there would always be time. Perhaps life spared me in this foolish fantasy, as our meeting might have left me more empty than full.

A few years later, when I became pregnant with my first child, Eliana, I thought often about my biological mother. I had more time in my mother’s womb than in her arms, and so that period fascinated me. Informed perhaps by some morbid fear, I recorded every miraculous sensation of my little girl growing within me. Someday, I’ll pass that journal onto Eliana. What I would have given to have an equal account from the woman who birthed me, some acknowledgement of my small place in her short life.

And so, I’ll continue writing, hoping that when I go, I’ll leave behind abounding words and stories for my family’s safe keeping. Which reminds me…for tonight’s “story in the head”, I must tell Elijah about when he was wrapped up in my womb. I was only three months pregnant, with no visible bump, and his twelve-month-old sister placed her hands on my belly, gently rubbing it and smiling up at me. She knew. I don’t know how she could have, but she knew I was growing her a brother. Elijah will like that story.

0 notes

Text

How I Came To Live in the Woods

Two years ago, my husband and I bought our dream house. This lovely seventies fixer-upper has robbed us of every last pound, consumed months of our time, and has signed us up for another decade of sweaty evenings and weekends spent painting, repairing, and renovating. We sometimes stop, paintbrush in hand, and ask each other, “any regrets?” Well…no—but we both pine for simpler times.

I look around and marvel at this big house and everything we’ve accumulated since our move to England. We arrived eight years ago with only a few suitcases and a handful of hopes. Unlike normal people, we didn’t ship our furniture and household goods from America. Instead, we had a massive yard sale and sold the rest on Craig’s List. I said goodbye to my sewing machine, guitar, bike, and camping equipment. We had to rebuy everything from brooms to blankets, dishes to clocks, silverware to shoes. It’s amazing how long it takes to rebuild your collection of stuff, especially when money is scarce.

Yet all this didn’t faze me. I was already well versed in the art of minimalism. When I was twenty-eight, all my worldly possessions resided inside the boot of my car. They would remain there for two years, while I tried out life as a vagabond. When you’re young, the promise of adventure can outweigh all fear. When it’s just you—no partner, no kids—just you and the great big sky, there are more chances you can take.

It all started after reading Brazilian writer Paulo Coelho’s book, “The Pilgrimage”, which sparked my desire to embark on a solo journey to Northern Spain to walk a 500-mile pilgrimage route that’s existed since the Middle Ages. Looking back, my decision to walk this ancient path set into motion a new trajectory for my life that wouldn’t be altered for several years. Walking the path for forty days, with nothing in my backpack but my journal, clothes, food, and water, certainly perfected my predilection for a minimal existence, but it was truly the time before and after the pilgrimage, that tested my resolve to embrace the unconventional life.

I was desperate to get to Spain. I had travelled the length and breadth of The States, but outside of a quick hop to London, I hadn’t properly travelled overseas. I didn’t have any form of savings to purchase a plane ticket or even feed myself for the two months I’d be gone, yet still, I couldn’t ignore the pull to go. I had a sharp distaste for fear and regret, and a stronger desire to be the bold protagonist in my own life story, so I needed to find a way.

I was living at the time in Flagstaff, Arizona. This high-desert mountain town boasts turquoise blue skies and perpetual sunshine to beckon everyone outdoors. At 7,000 feet above sea level, it’s cooler than its neighbouring desert towns, and yields deep winter snows that will never meet the cacti of the south. Flagstaff’s natural beauty draws an alternative collection of hikers, skiers, hippies, and transients. The cost of living is high, but the desire to be there great, and so many people find whatever means they can to stay. I had heard about a few odd souls who camped in the surrounding national forest for weeks at a time. I would be one of them. It was the most feasible means of funding my travels. I was renting an apartment then, with a kindred friend, Marike. Partial to avoiding conformity, she too, knew the value in travel and adventure, and so she wasn’t hard to convince. Together, we gave up our apartment to head for the woods. I quickly sold my furniture, giving away everything that wouldn’t fit inside my small Toyota. All I had left were my books, photos, clothing and gear.

Marike and I set up our first camp in a clearing of aspens and pines a mile down a long dirt lane. It was close enough to make the morning trek to work, yet far enough from the main road to ease our minds about cops or potential serial killers. My tent was narrow and thin, but sufficient. We’d forage for firewood, heat cans of soup on the stove at night and pour water for each other to wash up in the morning. Every other day, we’d pay to shower at the local hostel. Being April, the snow still fell, and so the coldest nights would find us curled up in the car beneath heaps of blankets, where sleep was fickle and fragmented. It was challenging, uncomfortable, and at times scary, but also exhilarating. The difficulties were dotted with starry skies, deep conversations, and the perpetual fresh mountain air that magically invigorated us despite it all. I felt raw and alive, my eyes open and senses heightened. My inner strength was blossoming, and my fears grew smaller, giving way to a confidence that began to permeate all aspects of my life.

Soon after, I left for Spain. Walking the pilgrimage was an epic alter reality that inspired and stimulated me daily. The path had brought many wonders and gifts—among them, a thirst for freedom, both internal and external. I felt tethered to nothing and life’s possibilities seemed boundless. The journey had liberated me from nearly all my money and material possessions, so when I returned to Flagstaff, I wasn’t ready to buy furniture, pay rent, and adopt a normal life. So, I returned to the woods. Marike had left for other adventures, and I was on my own, uncertain of how long I’d be there.

I was a vulnerable single woman alone in the forest, but through either ignorance or grace, I felt protected. I enjoyed the town and the trails by day and spent time with friends in the evening. I’d often find my way to the local bookstore before bed. Their late hours gave me a pseudo living room to read and write before driving back to the forest. On my way to the woods, I’d roll down the window to inhale the sweet smell of wood smoke escaping from well-lit houses, where people sprawled happily on couches, glasses of wine in hand. The line between liberating and lonely began to blur as winter closed in, but still, I was in a pleasant state of surrender. I believed life would shepherd me to extraordinary things, and magically it did.

At a random party, in a place I had never been, I met a married couple, Vickie and Bruce, who were soon to sail around the coast of Mexico for three months. I foolishly disregarded them as a wealthy privileged pair whom I’d have nothing in common with. Yet as our conversation grew, I quickly realised that they were making sacrifices to pursue their dreams, the same as I. And, when they asked me to look after their pets and home while they were away, I was humbled with euphoric gratitude. It was a blessed encounter that, not only granted me a home during the cold winter months but brought me a lasting friendship. For this couple, who were once two strangers, became dear friends. And their home became a haven of warmth and stability, to write, relax, and even grieve when my father unexpectedly died months after. And, two years later, when I met my husband, Vickie presided over our wedding.

Vickie and Bruce went on several long jaunts to Mexico, in which I was always happy to look after their home and pets. And in between, I found several other house-sitting jobs. I stayed in homes with hot tubs and hammocks, along rivers and among mountains. The most remote dwellings were quiet and wild, and I’d spy elk, coyote, and bear. Some were affluent, and afforded me weeks of luxury, soaking in big baths, lounging on plush furniture and dining in stylish kitchens. Others were more rustic. One January, I looked after a cat in a converted camper van on the edge of town. Without any electricity or water, the camper had only a small built-in wood burner to shield me from the worst of the winter cold. In three feet of snow, I’d chop logs into kindling and fall asleep to a roaring fire that demanded to be rebuilt several hours later, yanking me from sleep to action.

When one job finished, another would harmoniously begin. I only occasionally camped in the woods in the interims. Everything seemed to fall into place to facilitate this unconventional existence. It gave me courage, trust, confidence, and the precious gift of time. In escaping from the rat race, I bought myself time—to simply be—a luxury I have so little of now. It’s hard to believe I lived like that for two years. But in my wandering spell, I’d somehow cultivated true peace within myself. And even now, in life’s most constricting moments, my soul still wanders free because of it.

My vagabond days eventually proved their limitations, and I began to crave a place of my own. With great resistance, I exchanged my car—which brought me such freedom—for an apartment, where I acquired a rescue cat, a collection of mismatched furniture, and soon after, my husband.

I look around now at all this stuff—sofas and beds, tables and toys. I never thought I’d accumulate so much. Yet instead of weighing me down, it pleasantly anchors me. I think children need rooms and toys to call their own. As do I. And from the comfort of my couch, I now enjoy the smell of wine and wood-smoke from my own chimney. Someday I might don my backpack again and set off on another pilgrimage. Maybe I’ll even find a quiet spot in the forest to dwell for a while. But first, this house needs work and love, and as it’s filled to the brim, there is no more room for regret.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Novelty of the Home Swap

I am sitting in a strange woman’s kitchen in a small village called Bradley, in North Yorkshire, England. 100 miles away, this woman—who I know only by name and occupation—is at my home. We have swapped houses. Several years ago, I didn’t know that home swapping existed, but now, on our family’s fifth swap, I can firmly vouch for its credibility. So, while a woman and her husband, whom I’ve never met, sit at my sea-green kitchen table, I sit at theirs, indulging in the chocolate cake they’ve left me, and gathering clues about who this family is that lives here.

Their house is delightful. An old mill conversion, criss-crossed by large wooden beams and geometric ceilings, the fifteen-foot windows let light flow in from all directions. There are bounteous photos of mountains. Which, I suppose, is why they’ve chosen our house, to walk straight out the door and into the fells. Around me, there is evidence of children—two girls between the ages of ten and thirteen. I spy a card on the windowsill. Inside it reads…”Happy Stepmother’s Day…we love you”. They like antiques—an ancient rotary telephone, iron weighing scales, and china tea sets—and bunting; they are infatuated with bunting. Plentiful strings of handmade fabric flags adorn every window, carrying words like “love” and “home”. Over their kitchen counter hangs their motto: “Food, friends, family and fizz”. I make a mental note to leave them a bottle of Prosecco, and envision them in my kitchen, peering at the large photograph of my kids at two and three sitting in barrels of flowers in Tuscany. We scout the area—the parks, canals and castle—and at night we retire to their luxurious bed. Like sleeping inside a warm French baguette, it is pure layers of feathery comfort. I jab my husband in the middle of the night—"We have to get a better bed!”

At breakfast, Daddy puffs his chest and calls out his favourite question: “Is everybody happy?!” The kids raise their hands and quickly stand in their chairs, reaching their arms up high, singing “I am! I am!” They gobble up their cereal and happily explore the house, finding exciting games that could only be spawned by this setting. My husband notices the damaged laminate flooring in the kitchen, and the damp in the bathroom, his senses on alert from our own renovations. I’m happy he won’t be getting out his tools. Have the couple spotted our impending projects—the avocado green toilet or our painted 1970′s doors? What stories do our belongings tell? Will they like our up-cycled furniture and my colourfully abstract painting that hangs over the wood burner? Have they picked up my husband’s guitars or his travel guides?