"The world will never starve for want of wonders, but only for want of wonder." --Chesterton

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

On Dried Flowers and Pressed Leaves

I return again and again to my commonplace book, the pocket-sized hardback volume of quotes I have collected, mixed with my occasional thoughts. There the words of Seneca, Thoreau, and others combine to form a treasure chest of inspiration and comfort.

I often find myself poring through books looking for more gems to add to the collection. Emerson says we are too civil to books, reading four or five hundred pages for a few golden lines. We have seen how reading in this way can be a waste of our lives. I am guilty of this myself. Yet when it comes to my commonplace books, I am not trying to justify digging through trash heaps for diamonds. Instead, I chase life, the beating, wild heart of life—and when I catch glimpses of it, I try to capture something of it, in order to remind myself in the future.

I am reading Thoreau’s journal tonight, and this jumps out at me, from February 6, 1841. Thoreau is frustrated that the thoughts come out so jumbled in his notebook, but he reflects:

“Nature strews her nuts and flowers broadcast, and never collects them into heaps… Shall I transplant the primrose by the river’s brim, to set it by its sister on the mountain? This was the soil it grew in, this the hour it bloomed in. If sun, wind, and rain came here to cherish and expand it, shall not we come here to pluck it? Shall we require it to grow in a conservatory for our convenience?”

It’s the reason I find myself drawn so much to the journals and letters of writers I admire. Their finished, crafted pieces are one kind of brilliance; but the fragments of their thought are often the most valuable -- haphazard and strewn like seed as they are.

Seneca, writing in Letter XXXIII to Lucilius, advises his friend against the urge to collect aphorisms in a meaningless way, to pluck flowers and bring them home before we ever look at them:

“You wish me to close these letters also, as I closed my former letters, with certain utterances taken from the chiefs of our school. But they did not interest themselves in choice extracts; the whole texture of their work is full of strength… Wherever you direct your gaze, you will meet with something that might stand out from the rest, if the context in which you read it were not equally notable… For a man, however, whose progress is definite, to chase after choice extracts and to prop his weakness by the best known and the briefest sayings and to depend upon his memory, is disgraceful; it is time for him to lean on himself. He should make such maxims and not memorize them… What have you yourself said?... Take command, and utter some word which posterity will remember… Knowing means making everything your own; it means not depending on the copy and not all the time glancing back at the master.”

A collection of dried flowers, pressed leaves, preserved insects—that is a better metaphor for my little book. As you flip, there are petals and stalks, and a fading hint of scent. There are memories of the river’s brim, and the mountain.

But they are only memories, only maxims. I will not write a polemic against collecting—I, who love collecting so much. But the goal should never be to live only among faded and dried husks. They hang on our walls and interlace the pages of our books not to replace nature, but to remind us of her, to pull us back out the door into life. This is what it means to live in the place where everything is music. The withered ferns and sun-dried leaves are invitations to return to the dance.

All photos courtesy of Katie @ http://witheredfern.tumblr.com

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to Quit Reading So Much

“I had better never see a book,” wrote Ralph Waldo Emerson, “than to be warped by its attraction clean out of my own orbit, and made a satellite instead of a system. The one thing in the world, of value, is the active soul.”

Why do we read? Why study the thoughts of another?

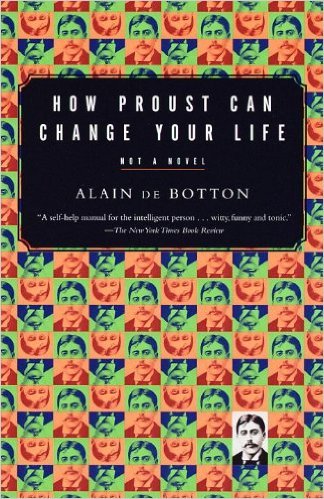

Marcel Proust weighs in: “There is no better way of coming to be aware of what one feels oneself than by trying to recreate in oneself what a master has felt. In this profound effort it is our thought itself that we bring out into the light, together with his.” Alain de Botton illuminates Proust by clarifying: “Not to pass the time, not out of detached curiosity, not out of a dispassionate wish to find out what Ruskin felt, but because, to repeat with italics, ‘there is no better way of coming to be aware of what one feels oneself than by trying to recreate in oneself what a master has felt.’”

If our goal is to cultivate our minds, the real value in books comes from their ability to make us think. In that process of interacting with a text, conversing with it, digesting it, we come to know ourselves better. Proust says, “We should read other people’s books in order to learn what we feel; it is our own thoughts we should be developing, even if it is another writer’s thoughts that help us do so.”

Yet Proust felt that this is where books stopped. As de Botton writes, “Books might open our eyes, sensitize us, enhance our powers of perception, but at a certain point they would stop, not by coincidence, not occasionally, not out of back luck, but inevitably, by definition, for the stark and simple reason that the author wasn’t us.” Proust:

“It is one of the great and wonderful characteristics of books (which allows us to see the role at once essential yet limited that reading may play in our spiritual lives) that for the author they may be called ‘Conclusions’ but for the reader ‘Incitements.’ We feel very strongly that our own wisdom begins where that of the author leaves off, and we would like him to provide us with answers when all he is able to do is provide us with desires… That is the value of reading, and also its inadequacy. To make it into a discipline is to give too large a role to what is only an incitement. Reading is on the threshold of the spiritual life; it can introduce us to it: it does not constitute it.

“As long as reading is for us the instigator whose magic keys have opened the door to those dwelling-places deep within us that we would not have known how to enter, its role in our lives is salutary. It becomes dangerous on the other hand, when, instead of awakening us to the personal life of the mind, reading tends to take its place, when the truth no longer appears to us as an ideal which we can realise only by the intimate progress of our own thought and the efforts of our heart, but as something material, deposited between the leaves of books like a honey fully prepared by others and which we need only take the trouble to reach down from the shelves of libraries and then sample passively in a perfect repose of body and mind.”

What is the lesson here? Only you are responsible for your happiness.

We have seen that we are responsible for seeking our art that connects to us and renews our vision of the beauty around us. We have also seen that we are responsible for loving by regularly reawakening to the mystery of another human being. Here the same principle applies. Just as we cannot be passive in appreciating art, just as we cannot be passive in our role as a lover, so we cannot be passive when we read, but must take responsibility for our own education. A book offers us a clue to living: and we must take that clue and begin tracking, begin stalking, being following every sign and signal back to the source. That is what Proust is calling the spiritual life, and what Emerson refers to as the life of the active soul. If we are able to retrain our minds to sense the real magic of the person we love, of the art we see, of the books read—there, we will find the beginning of the spiritual life.

I have been reading a dusty old book by Arnold Bennett, the 19th century “sage writer” (to use John Holloway’s term), called How to Live on Twenty-Four Hours a Day. When it comes to “serious reading,” Arnold’s advice is to find the books which strain us: “Now in the cultivation of the mind one of the most important factors is precisely the feeling of strain, of difficulty, of a task which one part of you is anxious to achieve and another part of you is anxious to shirk…”

How do we find a strenuous work that is right? To take a piece of advice from Proust again here, “A fulfilled academic life would…require us to judge that the writers we were studying articulated in their books a sufficient range of our own concerns.” What does this mean? Surely Proust is not advocating only selecting books that already fit our interest perfectly. Part of the goal of reading is to expand the sphere of our thinking. However, we must actively seek out something which we can connect to. Just as Proust visited art museums and compared the faces in famous paintings to people that he knew, so we can begin to find familiarities in the far fields of literature. Finding the right sort of book for ourselves gets easier with practice. It does not require digesting whole books. Emerson says, “We are too civil to books. For a few golden sentences we will turn over and actually read a volume of 4 or 5 hundred pages.” Instead of devoting yourself to something that will not connect to your heart, learn to pay attention to the clues: When you see one book or author mentioned in another book that you love, follow the trail. Look at the Suggested Reading and the Bibliography of something you would read again with pleasure. Or, as I have always found is best with poetry, simply flip through the pages and stop at random, letting your eye flirt with words, catching tantalizing glimpses rather than reading whole passages. Emerson says, “Learn to divine books, to feel those that you want without wasting much time over them... The glance reveals what the gaze obscures.”

Once we have found a work that meets these needs—something that is sufficiently challenging, and which we can connect to, what further advice does Bennett give?

First, “define the direction and scope of your efforts. Choose a limited period, or a limited subject, or a single author... And during a given period, to be settled beforehand, confine yourself to your choice. There is much pleasure to be derived from being a specialist.” Here we find again the art of limitation as a way of helping us focus, like Fredrik Sjöberg with his hoverflies, or the narrator of Alain de Botton’s Kiss & Tell with his Isabel. Do not let yourself become overwhelmed with the scope of the tasks you assign yourself. Be gracious, and forgiving. Instead of burning out, carry your work around inside you, steadily.

Secondly, Bennett tells us, we must think as well as read: “I know too many people who read and read, and for all the good it does them they might just as well cut bread-and-butter. They take to reading as better men take to drink. They fly through the shires of literature on a motor-car, their sole object being motion. They will tell you how many books they have read in a year.”

We must not read only, but give half our reading time to “careful, fatiguing reflection (it is an awful bore at first)… This means that your pace will be slow. Never mind. Forget the goal; think only of the surrounding country; and after a period, perhaps when you least expect it, you will suddenly find yourself in a lovely town on a hill.”

The goal of listening to music isn’t to reach the end. The goal of dancing isn’t to finish. The goal of reading isn’t to have read a book; it is to pick up a scent, and begin to make our lives about following the trail.

Proust says, “To make [reading] into a discipline is to give too large a role to what is only an incitement. Reading is on the threshold of the spiritual life; it can introduce us to it: it does not constitute it.” We are told that Shams threw Rumi’s books into the fountain; and it was Rumi who wrote things like, “Break all the glasses and draw near to the glassblower,” and “Don’t worry about saving these songs… We have fallen into the place where everything is music.”

This, then, is not an advocacy of not reading. It is an advocacy of slowing down, of reading carefully, of caring more for quality than quantity, of forgetting about the pace and focusing on the comprehension, retention, and application.

And, finally, knowing when to toss the book, because we have become the best parts of it.

De Botton, Alain. How Proust Can Change Your Life. 1998. Vintage International edition, 1998. Vintage (Random House), New York. 208 p. $16.00

1 note

·

View note

Text

How to Be a Good Lover

When loving and being loved is such a central part of our lives, why can it be so difficult? When we have such a strong desire to be loved, why do we find, in ourselves and in others, an inability to be good lovers? According to Marcel Proust, the difficulty of loving well is the same difficulty we experience in every other aspect of our lives: the “general difficulty of maintaining an appreciative relationship with anything or anyone that [is] always around.”

Growing accustomed to things and taking them for granted is a theme in human life. Alain de Botton, in How Proust Can Change Your Life, offers the example of technology: The telephone was invented in 1876, and by 1900, there were 30,000 phones in France, and in that short time, this wonder of technology was taken for granted. We can see parallels in our own rapidly developing technological world. We have standards for what we can accomplish, what we are patient enough to endure, and what we consume our time with that were unthinkable even 20 years ago. Everyone now carries and takes for granted a cellular device that can browse a global information system—along with the unfathomably large number of other uses the device may have. We take for granted that our vehicles will operate, without needing to understand how. We take for granted that clean water will come from the tap when we turn it on, and we don’t have to think hard about where it came from or where it goes when it empties into the drain. We take for granted anything we put into a waste bin will disappear when the garbage truck comes. We take the electricity for granted, and the heat, and protection from the elements. There is nothing in our lives that we cannot accustom ourselves to and forget about. Our luxuries have become necessities for us, and we still find ways to be discontent. We have so far alienated ourselves from nature that many of us can’t imagine living, or desiring to continue life, without those luxuries.

Similarly, in love, according to Proust, we will forget over time what our lives were like without our partner, we will fail to imaginatively remember what we have been given, and so we will begin to take for granted the current state of affairs, perhaps even feel safe enough to resent it and daydream of something else. Alain de Botton sums it up memorably: “Afraid of losing her, we forget all others. Sure of keeping her, we compare her with those others whom at once we prefer to her.” Habit can have such a dulling effect. “When you come to live with a woman, you will soon cease to see anything of what made you love her,” says Proust. And as de Botton writes, “Having something physically present sets up far from ideal circumstances in which to notice it. Presence may in fact be the very element that encourages us to ignore or neglect it, because we feel we have done all the work simply in securing visual contact.”

In the book Kiss & Tell the narrator recognized that his lack of knowledge about his lover wasn’t due to not knowing her—it was the opposite. He had come to know her too well, and so had circumscribed her in his mind. As de Botton says in his book on Proust:

“If long acquaintance with a lover so often breeds boredom, breeds a sense of knowing a person too well, the problem may ironically be that we do not know him or her well enough. Whereas the initial novelty of the relationship could leave us in no doubt as to our ignorance, the subsequent reliable physical presence of the lover and the routines of communal life can delude us into thinking that we have achieved genuine, and dull, familiarity…”

How, then, can we combat this loss of vision? If learning to see things freshly could be aided by the ability to refresh our imaginations with art that is more pertinent to our lives, how does this translate into the realm of love? Once again, de Botton suggests it has everything to do with imagination, and with the continual effort to wake ourselves up, to choose not passive intake, but active cultivation of a sense of wonder. This means paying attention to the details, listening carefully, remembering, and celebrating, among other things. But in addition to trying to “count our blessings,” de Botton suggests that the other side of the same coin may be helpful for us as well: deprivation, or, imaginatively seeing our lives without what we have.

“Deprivation quickly drives us into a process of appreciation, which is not to say that we have to be deprived in order to appreciate things, but rather that we should learn a lesson from what we naturally do when we lack something, and apply it to conditions where we don’t.”

This is why Proust felt that jealousy, despite its negativity, could reunite lovers: it reminded them of the lives they had without each other, and drove them without choice into the imaginative state of loss, from where they could once again appreciate what they had been given. But of course jealousy does not always work this way. To protect ourselves from the pain of jealousy, we prefer to become detached, angry, possessive, threatening—anything to reduce our emotional vulnerability and lay claim to something we have taken to be our right.

Proust’s challenge is to use our imaginations even when things are well, to never allow ourselves to think we have possessed another, to long for them, recognizing that inevitably, we will not have them forever. It is another way of waking up. I don’t simply mean asking how sad we would be without our lover, but really stepping back and seeing them as an individual, someone we can never fully possess, and someone who, despite our existential aloneness, is there by choice to offer love and companionship during the time available. By imagining our lives without the blessings we have, the goal is not to pity the sad picture of ourselves without our lover, but to reawaken ourselves to the astounding value of what we have. The protagonist of G. K. Chesterton’s Manalive finds unique and inspiring ways to awaken himself time and time again to the value of his life, his property, and his lover. His secret? Imaginative games.

If you find joy in challenging yourself, think of this as a challenge to learn mastery over yourself, and each encounter as another test to see if you can become who you desire to be. You have a natural ability to acclimatize yourself to your circumstances, not just in love, but in all of life. Will you accept that and grow staid? Or will you use the power of your imagination to come to value what you have?

Finally, how much success in love will this effort bring us? Alain de Botton discusses some of these ideas in a chapter he calls “How to Be Happy in Love,” but I think more accurately we are talking about, “How to Be a Good Lover.” For learning to love another to our fullest capacity does not guarantee happiness or success. We still crave to be loved well too. No matter the extraordinary effort we put into loving, if that effort is not returned, we may not find the happiness we desire.

There are two elements we seek in a lover. The first is who they are as a person, independent of us. This is the person we fell in love with when they charmed us with knowledge of a book we love, or surprised us with musical talent, or thrilled us with compassion toward strangers. The second element is who they are as a lover, and this is the person we fell in love with when they remembered something personal about us that we didn’t expect them to, when they bought us an unexpected gift, when they put their jacket around our shoulders. This second part of a lover involves how they dedicate themselves to loving us, but also how they control their negative qualities, and how capable they are of realigning themselves toward the essentials when things get difficult (particularly in those unguarded moments when they are tired, weak, frustrated, anxious, out of sorts, etc.). A person may be extraordinary as a human being, and still not be able to give us the love we desire. We can dedicate ourselves selflessly to an amazing individual, and we may learn valuable lessons from that process of loving, but we may also suffer if our love is not returned in the capacity we need.

Extraordinary people are individual and irreplaceable. But the quality of loving is more universal, and can be learned and developed with practice. And this is where Proust’s advice comes in. To him, imagination is the route to maintaining wonder, and helping us love to the greatest of our ability.

Thanks to Dana Ocker for the final two images. Visit DO Media Art @ domediaart.com

1 note

·

View note

Text

How to Open Your Eyes

Marcel Proust once wrote an essay on the philosophy of art which was never published, in which he consoled a young man who, whenever stricken with spleen or depression, was prone to traveling to extravagant places, or visiting the Louvre to look at paintings of palaces by Veronese, or harbor scenes by Claude, or princely lives by Van Dyck. Proust attempted to solve the young man’s problem by suggesting he visit the paintings of Jean-Baptiste Chardin. Chardin, in contrast to the other painters, chose simpler, more mundane objects: “bowls of fruit, jugs, coffeepots, loaves of bread, knives, glasses of wine, and slabs of meat.”

“These paintings,” writes Alain de Botton in his book How Proust Can Change Your Life, “were windows onto a world at once recognizably our own, yet uncommonly, wonderfully tempting.” This realignment of the young man’s aesthetic sense would teach him “that the kind of environment in which he lived could, for a fraction of the cost, have many of the charms he had previously associated only with palaces and the princely life. No longer would he feel painfully excluded from the aesthetic realm…” This is the method that a sensitive and kind-hearted Mole uses to revive his friend’s spirit when the River Rat has his heart broken with longing to travel to exotic places.

“Casually then, and with seeming indifference, the Mole turned his talk to the harvest that was being gathered in, the towering wagons and their straining teams, the growing ricks, and the large moon rising over bare acres dotted with sheaves. He talked of the reddening apples around, of the browning nuts, of jams and preserves and the distilling of cordials; till by easy stages such as these he reached midwinter, its hearty joys and its snug home life, and then he became simply lyrical.”

Recounting the beauties that the Rat had taken for granted by the simple fact of seeing them too often, Mole is able to create a longing in him for the things which he already possesses, and the Rat sits up and joins in, his dull eye brightening. How can we train ourselves to remember, day after day, the precious beauties of our life that we overlook because of habit? How can we learn to stop seeking happiness in the exotic, and see the exotic at our feet? How can we learn to stop the process of acquiring possessions to become happier, and instead learning that loving without possession, that heartbreaking work, is the only thing that can satisfy the deep longing of the heart?

***

But surely it’s not that simple. Are we not immediately drawn to some kinds of beauty and not others? We love flowers, not spiders. Isn’t there something to be said for the kind of beauty which draws us against our will, rather than the kind that takes patience and practice to see? Proust argues that “the immediacy with which aesthetic judgments arise should not fool us into assuming that their origins are entirely natural or their verdicts unalterable.” As much as we are drawn to beauty, we also learn what beauty is. It is a process of accumulation, and changes with experience. Artists teach us sensitivity to beauty where we might not have previously looked for it. Proust is “implying that our sense of beauty was not immobile, and could be sensitized by painters, who would, through their canvases, inculcate in us an appreciation of once neglected aesthetic qualities.”

This does not mean that the forms of beauty which are more natural to our inclinations are worth less—only that the hard-won sense of beauty that comes from the unexpected adds a certain intimate quality, in the same way that original expression can move us more than cliché. “Appreciating the beauty of crusty loaves does not preclude our interest in a chateau,” writes de Botton, “but failing to do so must call into question our overall capacity for appreciation.” This mode of appreciation “places the emphasis on a certain way of looking, as opposed to a mere process of acquiring or possessing.” Artists teach us how to appreciate more fully, to hone our sense of wonder, to actively engage in discovering and treasuring beauty in unexpected places—most often, ordinary and overlooked places.

This is the sense of wonder that I have written so much about, and which becomes the theme of so much of my writing. I don’t mean by “wonder” simply a passive emotional experience, but actively engaging with art and retraining the mind to be more sensitive to beauty. Wonder as I specially define it is a process in which we focus on learning how to see where one had not seen previously. “Beauty is something to be found, rather than passively encountered,” de Botton writes, and all of my favorite books, from Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek to G. K. Chesterton’s Manalive, confirm it.

***

So why do so many people miss it?

Alain de Botton tries to answer the question: “Why don’t we appreciate things more fully? The problem goes beyond inattention or laziness. It may also stem from insufficient exposure to images of beauty, which are close enough to our own world in order to guide and inspire us.”

Contemporary advertising finds great success in showing us desirable beauty which is disconnected from that which we already possess. The goal is for you to notice the more idealized life pictured, and purchase the items being advertised in order to move yourself closer to that life. Images are filtered and edited, and cropped from their context, in order to fit themselves more perfectly into our imagination, uncluttered with the difficulties of reality.

In The Romantic Movement, de Botton writes, “The magazine was an instrument of longing, but appeared moral in offering solutions to the human condition. Though it claimed to wish to satisfy its readers, the magazine had only performed its commercial—as opposed to literary—task when it left them miserable in the absence of a hundred items which would have to be bought. The magazine had to make Alice unhappy.”

What sort of art can we surround ourselves with in order to remind ourselves of the beauty of our own lives? Who can be our Chardin? For me, literature has served so often as a reminder of the value of my own life. Lately I’ve been appreciating the photography of my friend Dana Ocker, which I have included in this post. The photographs are a perfect example of how art can inspire us to see something we’ve overlooked so many times, and appreciate it anew because of the attention of the artist. There is a focus on particular details, on colors, on shapes. Metaphors suggest themselves, and will be unique to each person: looking at the image above, I’m struck by a sense of the two living trees standing together, contrasted with the lonely deadness of the tree beside. There is an attention to details here we might have overlooked; the photographs themselves are a practice in seeing. In fact, the entire movement toward art by the common person through the exchange of the internet opens up entire new realms of art to us that can remind us how to love what we had taken for granted.

But above and beyond the dependence on art to inspire us to see with fresh vision, we must resolve to practice if we wish to improve our capacity for appreciation. Like any other skill, sensitivity and awareness can develop with repetition and continual exposure. It comes down to a question of how much we can believe in the power of renewed vision to give us a deep and abiding happiness, and how much effort we are willing to invest to learn to see in this way.

Spring weather rolls in today. The temperatures rise, and the sun begins to appear earlier in the morning. Buds, evoking the qualities of resilience and patience, consider cracking with joy. Every year, spring is the time when people clean out their old lives, remind themselves of the important things, and begin to try again to live a better life. With a smile, I am listening as the robins and starlings at the top of the big oak sing with abandon.

All images courtesy of Dana Ocker. Visit Do Media Art @ domediaart.com

#Marcel Proust#Seeing#Art#Painting#Photography#Jean-Baptiste Chardin#The Wind in the Willows#Dana Ocker#Spring#Alain de Botton#How Proust Can Change Your Life#Beauty#Philosophy

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the Necessity of Limitations and the Joy of Collecting

In the summer of 2015, I took a trip to Hocking Hills, Ohio, a hidden Midwestern treasure. When you show people pictures of the incredible caves and waterfalls, they are understandably skeptical that such a place is found in Ohio. It is a wonderland of natural architecture. And it was here that I had a memorable first encounter. Descending a long staircase near one of the many waterfalls, I saw the people in front of me veer to one side, avoiding something on the wooden railing. The something is pictured above.

To the incredulity of my girlfriend and the others who passed us, I did not hesitate to approach and pick it up. Two large compound eyes, and a set of only two wings: this was not a wasp, but a fly. I sat down to let the creature continue its feast on beads of sweat, and thrilled at the fact that I had found my first hoverfly, a member of the family Syrphidae, a group of fantastic mimics. The humans veering to one side on the stairs were reacting exactly as they “should,” based on the evolutionary tactic of the family. These flies are harmless, and have no way to sting, but mimicry of more dangerous species allows them safety from predators.

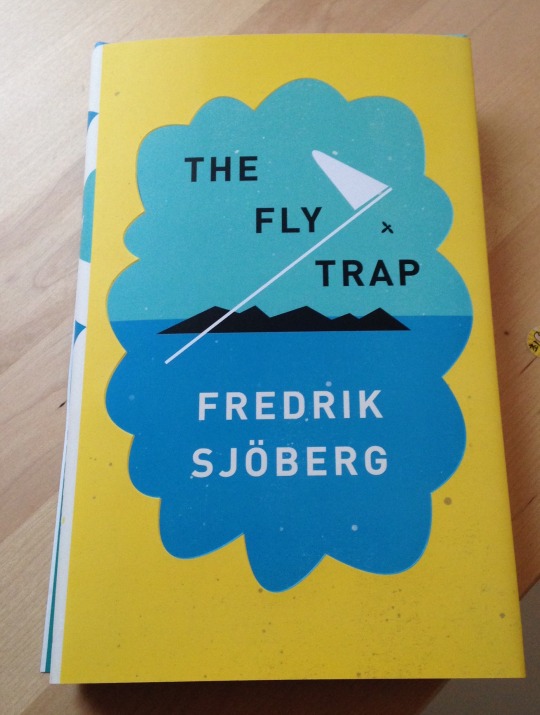

I fondly recalled this first hoverfly when reading the first book I finished in 2017, The Fly Trap, by the Swedish entomologist Fredrik Sjöberg, who specializes in these insects. Sjöberg’s book, though—to use a hackneyed phrase—is as much a book about hoverflies as Moby Dick is a book about whaling.

The Fly Trap is a personal memoir, a book by turns charming and heartbreaking. Sjöberg gives us the surface details of his life in such a way that we constantly hear something humming below. To read the book is to attune your senses just a little more to the metaphor and meaning underlying mundane circumstances. At first glance, the book is about a career spent loving and pursuing hoverflies; but underneath all of this, the author pours themes into his book. “Anyway, the hoverflies are only props,” he writes. “No, not only, but to some extent. Here and there, my story is about something else. Exactly what, I don’t know.”

We may each find our own list of themes that move us in the book. There is the theme of aimless travel as a way of trying to tame an overly romantic heart, and how often the author found himself “running away” from entomology, a profession he admits can be lonely, and one which doesn’t often appeal to the ladies. There is the theme of the value of slowness [“A theme granted me by nature. Which is probably just an unjustifiable simplification, a mental wild-goose chase, a poetic paraphrase meant to make a virtue of, or hide, a genetic inability to deal with choice.”]. There is the recurrent theme of how awkward our passions, so clearly vital to our own lives, can seem to others: he relates the embarrassing and often ridiculous encounters with strangers while out chasing and studying hoverflies.

Most significant to me, he composes a thematic ode to limitation. Using the metaphor of islands—for Sjöberg lives and studies his hoverflies on a Swedish isle—he celebrates the things that compress and contain us, thereby giving us the energy to live more fully. Referring to the window of time one has after planning an important trip, but before departure, Sjöberg writes:

“When the days are numbered, everything seems clearer, as if the time between preparation and departure possessed a particular magic. The endless stretch of time on the other side always struck me as evasive and treacherous. But the very limited period between now and then held a liberating peace and quiet. This allotment of time was an island. And the island became, later, a measurable moment. For a long time, this discovery was the only truly unclouded dividend that I took from my travels.”

Sjöberg finds island everywhere. He writes of the “irrepressible urge of curious boys to explore islands, even where islands don’t exist. Or, to be more exact, where islands are not to be discovered without the creative imagination that characterizes artists and good scientists.” It is the mind of an artist and scientist which elevates limitation to an art. While some may want to devote their lives to covering as vast and broad a selection of interests as possible, to drink in as much of the world as one can, the author is praising the study of minutiae, of counting every species of hoverfly, not in the world, but on his Swedish isle. The limitation brings a new glow to what we pursue, in the same way that a greater feeling of accomplishment can come from setting manageable goals, a way to avoid the feeling of being overwhelmed by the immensity of the tasks we have to accomplish.

Sjöberg is a hopeless romantic—and one of the most charming kinds, for instead of constantly laying his heart out for the reader, he flirts with us, only offering glimpses of a tender heart in the midst of longer, staid passages. How many times have I fallen into a mood of hypersensitivity to the emotional life, and wandered into a bookstore at night, where there are pools of light over books whose covers I brush with my fingertips, hoping that some author might befriend me in the way Sjöberg has? Sjöberg, in what seems a similar mood, finds pleasure in pursuing the lives of ordinary people. He chooses in the Fly Trap to focus on the Swedish entomologist who invented the Malaise trap for catching insects: René Edmond Malaise. He confesses a desire to chronicle the lives of underdogs, and in treating Malaise as a heroic figure, his task is similar to Alain de Botton’s narrator in Kiss & Tell: to make an epic of ordinary life, to see metaphor in the actions of another, and to see one’s own life projected onto theirs. This is another way of returning to The Fly Trap’s theme of limitation: to choose not the most famous of culturally significant of figures, but to show the curiosity and strangeness of the life of a forgotten man. Not only does this allow Sjöberg to do much research in an area where biographers aren’t profuse, but it also allows him to dedicate himself more fully to the more limiting constraints of studying a man whose biographical details are more scant. Just look choosing to study something as specific as hoverflies, he chooses to study a specific man’s life. There is sadness and beauty in the way the author follows Malaise through all of the details he uncovers: his ups and downs, his entomological success, his mysterious travels, and even his later crackpot theories about the island of Atlantis. To read Sjöberg’s pursuit of Malaise is almost like reading a detective novel; there is an energy and pace to the uncovering of Malaise’s life, and I forgot more than once that Sjöberg was studying an actual, historical person.

Returning to another theme we’ve talked about in regards to Alain de Botton’s The Romantic Movement, The Fly Trap celebrates the art of collecting. Using the term “buttonology” to refer to the exhaustive collection that someone with this near-manic hobby desires, the author writes: “The idea is to be exhaustive, to include everything. In this way, the buttonologist differs from the mapmaker, whom he resembles and can easily be confused with. But the person who makes maps can never include everything in his picture of reality, which remains a simplification no matter what scale he chooses. Both attempt to capture something and to preserve it. And yet they are very different.” Sjöberg speculates uneasily that perhaps the buttonologist is an erstwhile mapmaker on his way to madness.

The desire to collect exhaustively is present in some minds more than others, but seems to be a somewhat universal human trait. How many hours have been plagued by the anal-retentive desire to perfect a collection? I’ll be more direct: How many hours have I spent poring through my collection of books, hoping to perfect it as a symbolic representation of who I am? How many hours have I spent collecting leaves, as though the trees themselves could not be seen if I did not press their leaves into my notebook? Sjöberg speculates on what motivates collectors and completionists to go to the lengths that they do: “The German-American psychoanalyst Werner Muensterberger has pointed out that many collectors collect to escape the dreadful depressions that constantly pursue them… in a form of fetishism that does indeed allay anxiety.” However, Sjöberg draws a line between artificial and natural objects, and says that natural objects are not fetishes in the same way: “One reason is that they can seldom be purchased for money. In addition, they almost always lack cultural provenance.” To collect leaves, then, is to Sjöberg a healthier obsession, and, we might add, one which also serves to connect us more viscerally to surrounding nature, arguably something every human being needs for a sense of well-being. It’s simply a task of learning when to use the energy of collecting, and when to let go and remind ourselves of a more fundamental sense of being.

In celebrating limitation, in choosing a single biography to focus on, in choosing a single family of insects to study, in choosing to find islands in all of the circumstances of life, Sjöberg is also writing about control. “In exercising control over something, however insignificant and apparently meaningless, there is a peaceful euphoria, however ephemeral and fleeting,” he writes. His book is also about the tension between his sensitive heart and the control he tries to gain over it. Perhaps sensitive and emotionally-driven people are more likely to collect as a means to focusing energy into something constructive (no matter how practically useless the collection, or how futile the goal of collecting exhaustively), a means of curbing excess of heartache and finding purpose, and so positivity.

Finally, there is a sudden, heartrending beauty to many of the passages in The Fly Trap. “Purple loosestrife sways in the light sea breeze. The heavy smell of seaweed. Arctic terns!” exclaims a man in love. Or, in closing, take this heartfelt reverie on the color of maple blossoms in the spring:

“The colour alone puts me in a good mood. Maple blossoms are greenish yellow, and the tender leaves a yellowish green—and not the other way around. From a distance, the mix of these two tones creates a third so beautiful that the language lacks a word to describe it. As we all know, greenery deepens in colour as summer comes on, but the blooming of the maples is when it all begins, when everything is at its brightest and best. Just a week, maybe two, and then the alders burst into lead in deadly earnest. I wish so profoundly that everyone knew. ‘Maples blossoming.’ Those two words on answering machines would be enough. Everyone would get the message. They’d see the colour, sense its nuance, understand. Know then that everything flies, absolutely everything. A thousand commentaries. An entire apparatus of footnotes.”

(Credit to Dana Ocker for the 3rd and 7th images. http://www.domediaart.com )

Sjöberg, Fredrik. The Fly Trap. 2004. Translated by Thomas Zeal, 2014. Vintage Book edition August 2016. Vintage (Penguin Random House LLC), New York. 278 p. $17.00

1 note

·

View note

Text

On Learning the Life of Another

What is the most we can understand another human being? What is the greatest depth to which we can penetrate, the most empathy we can feel? Most humans, Alain de Botton reflects, disregard the rich layers of the lives of their fellows—“their chronologies and earliest snaps, their letters and diaries, the locations of their youth and maturity, their school bench and wedding parties.” What if we dedicated ourselves to really learning the life of another?

Kiss & Tell (1995), the third book published by Alain de Botton, is, along with The Romantic Movement, part of the early writing which he has since disavowed. But the book is a cache of inspiring thought, and one which shouldn’t be overlooked. Similar in style to his first two books, this is what I’ve called an “expositional novel,” a book of ideas using the format of storytelling as a base from which to leap into speculation.

Accused of a lack of self-awareness while at the same time being self-obsessed and blind to others, the narrator of Kiss & Tell responds to the criticism as a challenge, and comes up with the idea of writing a biography about a total stranger. Flouting many of the conventions of biography, he does not a famous or culturally significant person, but an ordinary woman he meets at a party named Isabel. Instead of eliminating himself and writing an impersonal biography, the narrator includes his own thoughts and impressions, one of the most valuable aspects of the book, and one which he says has been missing since Boswell—a noble biographical tradition which he would like to see regain popularity. Reflecting on Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle, he concludes that an honest biography must arise from the relationship between author and subject.

Beginning in a conventionally linear fashion with a description of Isabel’s childhood, the narrator pauses, feeling the dishonesty of this approach, and instead breaks into dialogue of early conversations he has with her, in the manner of a novel. Privileging “the early dates over the early years,” he chooses to write about his first dates with Isabel, and allows her past to rise naturally to the surface of the present. There cannot be, he asserts, a definitive biography of Isabel or of anyone, but only a series of perspectives, impressions, and memories. Instead of aiming toward the impossible goal of definition, the narrator celebrates subjectivity and imperfection—and this is the deeply valuable merit of De Botton’s approach.

In a wise and memorable passage, the narrator reflects that “it is not ignorance which damages the clarity of our portraits, but the accumulation of knowledge. It is the length of time we spend with others which muddies our schemas…” It is our familiarity, and our rapid acclimatization to another, which blinds us to what is unique and wonderful about them. The narrator describes this as “the paradox that the more one has a chance to talk to someone, the less one in fact will… By virtue of sharing a life, the upheaval of a grand enquiry may be avoided. Knowledge implies a degree of possession… Moreover, the longer one has known someone, the more shameful it is not to have grasped things about them.” In addition to this, the desire for love also blinds us to the freshness of vision we may need to really see a person and listen well to who they are: “We never misunderstand people as extravagantly as in our emotional life, for never are we more committed to a person’s aptness that when we have fallen in love with them, never do we seek to forget with such vehemence their more inconvenient evils.”

An analogy is offered of “cracking open a novel and at once forming an idea of the characters.” To read a novel well, we must not leave it on the shelf and assume its contents; we must not project our own desires onto its contents and assume we have understood it; we must not rush through it, hoping to glean the most pertinent information in a flurry. Instead, to really get to know the characters of a novel takes time and patience.

___

In biographies, there is often much information which even the subject of the biography may not have been aware of. For example, what if instead of designing a family tree including all of Isabel’s relatives, the narrator could instead construct a family tree from her memories of her family, and the details and memories associated with those family members? In other words, there might be some question marks on the tree, some misremembered names, and some associative details that have stuck most in Isabel’s mind. If we really want to understand a person, part of that task, the narrator suggests, is seeing the objective facts of their life through the subjective lens. Here again, the imperfection of the record is celebrated, as it brings with it the more genuine and personal account of a life.

Later, the narrator also reflects on how memories and stories change depending on present circumstances. A very different autobiographical tale is woven when one is happy and when one is sad. It is notable that even from the subjective point of view, the details of the story will move and sway in the ocean of present experience. Despite the fact that “prompting someone to remember their past is akin to forcing them to sneeze at gun-point,” the patience of the narrator’s approach, and his increasingly close relationship with his subject, allows him to catch her in unguarded moments, like the scene where she lies awake sleepless remembering her past relationships, and due to the loose connection between the narrator and his subject, these shared tales of love and mishap are fascinating, and keep them up late well into the morning.

Finding that much of the intimate lives of subjects are left out of biographies, the narrator structures his story around the events which most consume Isabel’s life. He includes in this list the food Isabel likes and the songs she listens to, which serve as Proustian involuntary memory triggers for her. Instead of getting frustrated with the time she spends doing her makeup, he asks her to show him what she does, and, with delight, she gives a step-by-step explanation of the techniques she uses.

Kiss & Tell is a book of experiments. When we meet others for the first time, or find them again after weeks apart, we can see them with fresh vision, and we have a chance at recognizing their irreplaceable qualities. So with the vigor of a wind of fresh air, the narrator plunges wholeheartedly into really trying to see another’s life, chasing the ideal of “understanding a human being as fully as one person could hope to understand another, submerging myself in a life other than my own, seeing the world through new eyes…” The book is a collection of ways to go about that process. It is a valuable lesson in attention, in remembering, and in loving.

It might do us good to practice the art of dedicating ourselves to the life of another in the way of a biographer, but without distancing ourselves or needlessly eliminating ourselves from the equation. Listen with everything you have, watch closely, notice the details, taste the life of another human being.

(Images 1, 4, and 5 courtesy of Dana Ocker at DO Media: domediaart.com)

De Botton, Alain. Kiss & Tell. 1996. Reissue edition 1997. Picador, New York. 288 p. $17.00

1 note

·

View note

Text

On Our Past Lovers, and the Tension Between Collecting Everything and Starting Over

Where does our experience go? When relationships end and life situations change, what happens to the discarded skins of who we were? Alain de Botton writes,

“To go to bed with another is in some way to collide with the memories and habits of all those they have ever slept with. Our way of making love embodies the mnemonic of our sexual history, a kiss is an enriched model of past kisses, our behaviour in the bedroom filled with traces of past bedrooms in which we have slept.”

This is from his forgotten second book The Romantic Movement: Sex, Shopping, and the Novel (1994), what I might call an expositional novel, a book chock full of ideas about relationships and the psychology of how we love. While telling the story of the relationship between Alice and Eric, De Botton finds many narrative cues to leap into psychological and philosophical speculation. Showcasing a broad range of cultural and literary references that speak to and enlighten one another, he has created a kind of encyclopedia of love.

De Botton suggests that we carry past lovers into every area of our lives, regardless of how aware of them we are. It might be in a tic we have picked up, or the phrasing of certain sentences; the way we kiss, or the things we find funny. The past clings to us.

“Though a sexual history may have been desirable from a purely mechanical point of view, it revealed a psychological complexity. To have a sexual history did not only imply one had made love to a succession of people, it also suggested one had either rejected or been rejected by these same bedroom companions. A more melancholy way of looking at the history of sexual technique was to read it as a history of disappointment. There was hence a curious tension in the proceedings: on the one hand, the lovers appeared to be reinventing the world through their passion; on the other, their gestures carried evidence of a past from which they had had to keep travelling.”

Many of us assure ourselves that no experience is wasted, and that it is choice, not failure, which leads us on to new experience. Many of us revolt against this view of history, and choose to view each new encounter as a recreation of ourselves, as a deliberate choice to draw a line between past experiences and now.

“The energy of Alice’s love making symbolized a revolt against such history, she wanted to forget other kisses and nights which had begun like this, energetic and intense, before ending in recriminations, he declaring he couldn’t commit, she disgusted by the look of his vacant face behind the morning paper.

“How great the longing seems to be that ‘there should have been nothing or no one before I arrived here,’ a relic of the [virgin] Berkeleyan fantasy that ‘perhaps I invented a world, perhaps the world was born along with me, and I am its creator.’ Nietzsche famously complained that the most common oversight of philosophers was to ignore the historical dimension of subjects, and even outside the academy, there are countless cruel examples of revolutionaries who have wished to start the world at the year zero. A deep ambivalence seems to reside in the approach to history—on the one hand, a desire to preserve everything [encyclopedism], on the other, the desire to start everything anew [revolution].”

And here De Botton opens up a tension which is live and electric—that between preservation and revolution. Are you the kind of person who likes to save everything—the collector, the pack-rat, the encyclopedist? Or do you prefer the opposite—to rid yourself of the old, to be a revolutionary?

I find both desires so prevalent in me, and their opposition has produced much energy. I cherish the feeling of psychological renewal that comes from cleaning out the old and starting anew, in beginning new notebooks, in marking dates on the calendars as fresh starts. Yet I have tried to detail in writing the experiences of my life, supplementing this with pictures, videos, and sound files—scrapping together an encyclopedia of my life--and I take pleasure from its completeness. I am also an avid collector, and this desire to collect has often been at war with the opposing desire to have less.

I believe it is possible to celebrate newness and revolution, and also to see the continuity of our lives, to celebrate the many lovers who have inspired and helped create our kiss, the many lives whose influence helped us become the people we are today. It is possible to take creative energy from the tension between our desire to collect and our desire to regularly renew ourselves. There is value for living in both becoming a new person, and in seeing the unity of the thread of our lives.

2 notes

·

View notes