25 ~ Gradblr ~ Chemistry Graduate Student in Los Angeles ~ studying and research with a mental illness~

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

finding out that my group leader is actually one of the better ones at my institute while I'm working hard to apply to become a group leader bc i know I would be better than him is. hmm. an interesting place to be

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

having a freeze response to stress is so funny in the context of normal adult stressors. millions of years of evolution are trying to tell me that the email will not find me if i stay very still and do nothing

#overcame my freeze response for:#(a) writing and email to a new experimental collaborator and sending her my fellowship proposal#and (b) doing my fucking taxes#I owed $0 baybee#joys of being paid not-very-well overseas via a tax-free fellowship

142K notes

·

View notes

Text

Running into the issue that I’m good for the level that I’m at, but I want to be good compared to like. The leaders in the field. Which is a big standard to aspire to!! And stressful!! But goddamn, I *want* it.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Having a slightly time giving a PhD student advice because she’s always comparing herself to me, and she’s really good! But I have 3 years on her and am (by the evaluation of several people) exceptional. But I think she’s asking really good questions and doing all the things *I* did so I think she’ll be great, but I really need to figure out how to keep from discouraging her via comparison to where I am now

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's always so weird that like. Fully a third of job listings I see in machine learning are for biomedical research. And easily two thirds of postdocs. Massive, huge family of applications that seems completely absent from the public discourse. From the way people talk about it you'd think half the field works in image generation and nobody does medical research, but in reality only a tiny handful of people seem to be doing image generation, and everyone else is either doing language models or studying cancer and designing novel drugs

#oh yeah i use ML all the time in my work#in multiple ways!#it's really helpful for the stuff I do!#HOWEVER#very away for GIGO (garbage in garbage out)#and so many of the people I work with keep loving chapgpt#and using it to write a bunch of things#and i have to keep telling them that they're straight up not learning some skills that they need by doing that#like i know you don't want to write your paper!#but that's a really big part of science! the communicating it part!#and if you don't develop those skills you might as well not bother in science#so yeah.#i'm both pro and anti AI#well pro ML anti AI#even tho they're the same but not really in public perception

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Actually, (Biden HHS secretary) Xavier Beccera, going toe-to-toe with social media WAS your job. And you were bad at it.

“I can’t go toe to toe with social media,” Becerra said in a wide-ranging interview Wednesday, arguing that even a Cabinet secretary can be hemmed in. As examples, Becerra cited the lawsuits the Biden administration faced after urging social media companies to take down posts the White House considered disinformation. And he noted that officials can’t formally disclose many details about negotiations to lower prescription drug prices. “I don’t get to write whatever I want,” he said. The health secretary never mentioned Robert F. Kennedy Jr., but the longtime anti-vaccine activist’s shadow hung over Becerra’s answers. President-elect Donald Trump’s pick to run HHS has relentlessly criticized the agencies he soon may lead, amplified false claims about vaccines and offered alternatives to what he called government misinformation. Now, Kennedy, who has said he is not anti-vaccine, could occupy the office where Becerra was giving his exit interview.

Okay, I hear what he's saying, but here's something I've been saying since the first days of the last plague:

Effective public science education is a core part of the job of public health.

As soon as it became obvious that nobody in public health was doing public communication at all well, I started asking around. There's a first-rate college of Public Health just up the road from me; how many semesters of communication do they require to graduate with a masters degree in public health?

One. At the college sophomore level.

Yikes.

Y'know, my ex-wife was a technical writer, entered the field just as they were switching from hiring male engineers to female english majors, specifically because they found out that it was easier to teach engineering to english graduates than it was to teach engineers how to write coherently.

Public health administrators and staff don't need to be first-rate epidemiologists. They need to know enough about epidemiologists to understand what they're being told by the people in the actual contagious-disease labs and by the statisticians. What they do need to be is first-rate communicators. And they're just not. All the first-rate (and even more of the second-rate) communicators are on the anti-public-health side. May god have mercy on our souls, though mercy merit we none, because as a society we gotta fix this.

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

The thing about academia is that one day you’ll be doing complicated computational modeling of some system or another, and the next day you’ll be making stop-motion animation with PowerPoint

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think the reader's response to this post is probably going to either be "That's incredibly minor" or "Holy shit YES I'M ALSO PROUD", depending on people's personal experiences with academia, but:

Today I am incredibly proud of one of my students.

In the interests of disguising identities, let's call them Ceri. Ceri is one of my third year undergrads (meaning their final year, for anyone unfamiliar with UK uni systems.) They transferred to us last year, and within two weeks I was giving them the contact info to get to Student Services and get themself screened for ADHD; they have some mental health struggles, but I clocked pretty quickly that they STRUGGLE with procrastination, and punctuality, and attending 9am lectures in particular. Naturally, as is the way of my people, it took them a further four months to remember to go to the screening. Lol. Lmao. Rofl, in fact.

But, they did it eventually! Their screening lit up like a Christmas tree at the ADHD section, and they got a free laptop and optional one week extensions and a study support worker named Claire. This has helped tremendously, and although mental health + until-then-unsupported ADHD meant their academic profile had slid sideways somewhat, with the new tools available and a couple of resits they passed the year and hit this year running.

Until, that is, the last fortnight.

Now, I take them for a Habitat Management module that has two assessments: an academic poster presentation before Christmas, and a site-specific management plan in May. Naturally this means we are at that happy point in the year for the poster presentations. I give out the briefs at the start of the year, so they've had them since October; I've also been periodically checking in with them all for weeks, to make sure they don't have any major burning questions. The poster presentation was to pick a species reintroduction project, pull the habitat feasibility study out of it, and then critique that study; Ceri chose to look at the hen harrier reintroductions proposed for the southern UK. All good.

Which brings us nicely to today! Ceri's presentation is scheduled for 2.30. At 11am-1pm, I am lecturing the first years on Biodiversity, while Ceri is learning about environmental impact assessment with a colleague I shall call Aeron. This means we are separately occupied during those same hours.

Nevertheless, Aeron messages me at about 12.

"I think Ceri needs to see you after your lecture," he writes. "They're panicking, I genuinely think they might cry. I'm worried. Are you free at 1?"

I say I am. At 1, I get lunch and sit in the common area; Ceri comes to see me. To my personal shame, imagine all of the following takes place while I stuff my face with potato.

Now: this part is going to be uncomfortably familiar to anyone who has ever tried higher education with ADHD, especially unmedicated. It certainly was for me. All I can say is, I never had the courage to take the step here that Ceri did.

"I have to confess," they said quietly, and Aeron was right, they were fighting back tears. "My mental health has been so, so bad for the last fortnight. I've left it way, way too late. I don't have anything to present."

"Nothing at all?" I asked.

"I've been researching," they said helplessly. "I found loads on the decline of the hen harrier. But it wasn't until last night that I finally found a habitat feasibility study to critique. Generally... I've been burying my head about it, and it just got later and later. I thought I should come in for Aeron's lecture, and I should at least tell you."

This part is a minor thing, right? But honestly, I remember being in the grip of that particular shame spiral. I never did manage to tell my lecturers to their faces. I just avoided. I honestly can't imagine having the courage it took them to come in and tell me this, rather than just staying home and avoiding me.

"I think..." they said hesitantly, "I know I can submit up to a week late, for a capped mark. I think I need to do that, and apply for extenuating circumstances. But then I'll have both Aeron's assignment and yours due at the same time."

Which meant they would crumble under the pressure and likely struggle to pass both; so me, being as noble and heroic as I unarguably am, stopped eating potato and said, "Let's make that plan B."

(It was good potato. I am a hero.)

So, we made plan A: I moved their timeslot to 4.30, giving them three and a half hours. The shining piece of luck in this whole thing was that this was the crunch time assignment - if it had been Aeron's, they'd have had to try and write a 3000 report in that time. But for me, all they had to write was an academic poster, and those things are light on words by design. We found them a Canva template, and then we quickly sketched out a recommended structure based on the brief: if it's habitat feasibility, look at food availability, nesting site availability, and mortality risks in the target release site. Bullet point each. Bullet point how well the study assessed each. Write a quick intro and conclusion. Take notes as you go, and present the poster itself at 4.30.

"You think I should try?" they asked doubtfully, looking like I'd just asked them to go mano-a-mano with a feral badger.

"If you run out of time, so be it," I said. "But your brain is trying to protect you from a non-existent tiger. That's why you've procrastinated - it's been horrible, and you've been shame spiralling, and your brain is trying to shield you from the negative experience; but it's the wrong type of help for this situation! So while you're sitting there working on it, hating life, every time your brain goes 'This is hopeless, I can't do it', you think right back 'Yes I can, it just sucks.' And you carry on. Good?"

"Good," they said. "I'm going to mainline coffee and hole up in the library. Enjoy your potato."

And then, of course, I had to go and watch the other students' presentations, so that was the end of me being any help at all. I spent all afternoon wondering if they were going to manage it, or if I would be getting a message at 4.25 telling me they'd failed, and would have to submit late and hope for an EC.

And Tumblrs

Tumblrs

Let me FUCKING tell you

They turned up at 4.15, fifteen minutes early, wearing a mask of grim, harrowed determination and fuelled by spite and coffee, and they pulled up that poster and started presenting and yes, okay, I'll admit their actual delivery was dramatically unpolished and yes, they forgot to include the taxanomic name for the hen harrier on the poster and yes, fine, I admit that there were more than a few awkward moments where they lost their place in their hastily scribbled notebook but LET ME FUCKING TELL YOU -

They smashed it. It was well-critiqued, it had a map, it had full citations, it had a section on the hen harrier's specific ecology and role in the ecosystem, it had notes on their specific conservation measures. They described case studies they'd read about elsewhere. They answered the questions we threw at them with competence and depth. There was analysis. All that background research they'd done came right to the fore. They were even within the time limit by 15 seconds.

You would never have known they'd produced it in three hours, from a quivering and terrified mess fighting the bodily urge to dehydrate via tear ducts. After they left, the second marker and I looked at each other and went "So that was a 2:1, right?"

I caught up with Aeron downstairs and he was beaming. Apparently Ceri had seen him on their way out, and had gone over to talk to him. Aeron said the difference between the Ceri of this morning and the Ceri of then was like two different people; in four hours, they'd gone from their voice literally breaking as they admitted the problem, ashamed and broken, to being relaxed and happy and smiling.

"I reckon I've passed," they apparently told Aeron, pleased. "Maybe even a 2:2. There's things I wish I'd had the time to do better, but I'll be happy if I passed."

They won't know until late January what they got, because we're not allowed to release marks until 20 term days after hand-in, and the Christmas holidays are about to hit. But I'm really hoping I can be there when they're released.

But mostly, I'm just... insanely proud of them. I cannot tell you how happy I am. And I know, I know, obviously this is not a practice I would want to see them do regularly, or indeed ever again, and it only worked because they were fucking lucky with the assignment format, but like... when life is just punching you in the face, and you hit a breaking point... isn't it nice? That just this once, you pull off a miracle, and it's fixed? The disaster you thought was about to ruin you is gone? To get that relief?

Anyway. Super super proud today.

#do i want to be a professor to help other neurodivergent students make it through/into academia actually???#have to decide#research or research+teaching... hmm

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

lol just realized that between us, me and my parents account for more than half of people who have published scientific papers with our specific (pretty rare) last name. Wild! Soz to Sven and Mathias

#lmao#I’m hoping to end up being the most prolific one tho#let’s gooooo#also just got my first paper in my postdoc published#yaaaaay

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

VERY funny to me to get paper reviews back where like the whole second reviewer was just nit-picking italicizing of variables, and if the figure legend of the SI figures had the correct letters in subscript

#lmao#actually these are some really positive reviews which is very nice to finally get#annoying that the persnicketyness and attention to detail that I moved to Germany for#and have since complained about#is leading me to do better science

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The continuing release of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere is a major driver of global warming and climate change with increased extreme weather events. Researchers at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU) have now presented a method for effectively converting carbon dioxide into ethanol, which is then available as a sustainable raw material for chemical applications. "We can remove the greenhouse gas CO₂ from the environment and reintroduce it into a sustainable carbon cycle," explained Professor Carsten Streb from the JGU Department of Chemistry. His research group has shown how carbon dioxide can be converted to ethanol by means of electrocatalysis.

Continue Reading.

955 notes

·

View notes

Text

you know what else fucks me up about the US election? one of the things that has left me reeling in bewilderment and grief this month?

I'm a scientist, y'all.

That means that I am, like most American research scientists, a federal contractor. (Possibly employee. It's confusing, and it fucks with my taxes being a postdoctoral researcher.) I get paid because someone, in the long run ideally me, makes a really, really detailed pitch to one of several federal grant agencies that the nation would really be missing out if I couldn't follow up on these thoughts and find concrete evidence about whether or not I'm right.

Currently, my personal salary is dependent on a whole department of scientists convincing one of the largest and most powerful granting agencies that they have a program that is really good at training scientists that can think deeply about the priorities of the agency. Those priorities are defined by the guy who runs the agency, and he gets to hire whatever qualified people he wants. That guy? The Presidential Administration picks that one. That's how federal agencies get staffed: the President's administration nominates them.

All of the heads of these agencies are personally nominated by the president and their administration. They are people of enormous power whose job is to administer million-dollar grants to the scientists competing urgently for limited funds. A million dollars often doesn't go farther than a couple of years when it's intended to pay for absolutely everything to do with a particular pitch, including salaries of your trainees, all materials, travel expenses, promoting the work among other researchers, all of it—so most smart American researchers are working fervently on grants all the time.

The next director of the NIH will be a Trump appointee, if he notices and thinks to appoint one. NSF, too; that's the group that funds your ecology and your astroscience and your experimental mathematics and physics and chemistry, the stuff that doesn't have industry funding and industry priorities. USDA. DOE, that's who does a lot of the climate change mitigation and renewable energy source research, they'll just be lucky if they can do anything again because Trump nigh gutted them last time.

Right now, I am working on the very tail end of a grant's funding and I am scurrying to make sure I stay employed. So I'm thinking very closely about federal agency priorities, okay? And I'm thinking that the funding climate for science is going to get a lot fucking leaner. I'm seeing what the American people think of scientists, and about whether my job is worth doing. It's been a lean twelve years in this gig, okay? Every time the federal government gets fucked up, that impacts my job, it means that I have to hustle even harder to get grants in that let me support myself—and, if I have any trainees, their budding careers as well!—to patch over the lean times as much as we can.

So I've been reeling this week thinking about how funding agency priorities are going to change. I work on sex differences in motivation, so let me tell you, the politics reading this one for my next pitch are going to be fun. I'm working on a submission for an explicitly DEI-oriented five year grant with a cycle ending in February, so that's going to be an exercise in hoping that the agency employees at the middle levels (the ones that know how to get things done which can't be replaced immediately with yes men) can buffer the decisions of those big bosses long enough to let that program continue to exist a little while longer.

Ah, Christ, he promised Health & Human Services (which houses the NIH) to RFK, didn't he? We'll see how that pans out.

I keep seeing people calling for more governmental shutdowns on the left now, and it makes me want to scream. The government being gridlocked means the funding that researchers like me need doesn't come, okay? When the DOE can't say fucking "climate change," when the USDA hemorrhages its workers when the agency is dragged halfway across the country, when I watch a major Texan House rep stake his career on trying to destroy the NSF, I think: this is what you people think of us. I think: how little scientists are valued as public workers. I think: how little

This is why I described voting as harm reduction. Even if two candidates are "the same" on one thing you care about, they probably aren't the same level of bad on everything. Your job is to figure out what that person would do in this job. It's not about a fucking tribalist horse race. A vote is your opinion on a job interview, you fucks. We have to work with this person.

Anyway, I'm probably going to go back to shaking quietly in despair for a little longer and then pick myself up and hit the grind again. If I'm fast, I might still get the grant in this miserable climate if I run, and I might get to actually keep on what I'm trying to do, which is bring research on sex differences, neurodivergence and energy balance as informed by non-binary gender perspectives and disability theory to neuroscience.

Fuck.

577 notes

·

View notes

Text

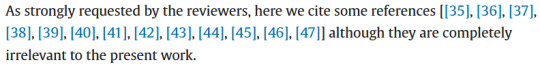

[As strongly requested by the reviewers, here we cite some references [[35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47]] although they are completely irrelevant to the present work.]

Yang et al. (2024)

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

I had a really nice seminar today about communicating in science as a woman, and it was just so nice to discuss all of the toxic behavior in our institute, and then did a lot of workshopping about useful strategies to deal with typical sexist experiences

#it was also nice just to discuss this with women across different institutes and levels of seniority (masters student to group leader)#esp since i'm interviewing to be a (junior) group leader next week#(!!!)#and I want to think about ways I can be an effective leader#and also protect and prepare my future students from the bullshit that is academia#and also let them enjoy academia the way that I've been able to

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

omg i'm crying, the postdoc i work with just told me that he wished that i had been his phd supervisor because not only do i discuss science with him, but i tell him how to improve and be better and that he's excited for me to become a supervisor and mentor so many people 😭😭😭

#ugh i love validation#put in an application to become a group leader last week#will see how it goes etc#but it's just nice to really solidify that not only am i a really good scientist#but i'm also a fab mentor and a good manager or other people's projects#i'm so excited for the next stage ngl#i really hope it happens sooner rather than later

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

feedback from my academic supervisor has me doubting if I should try and continue working with him as a group leader

#i think the app will be submitted today#unless he got mad about the work and pulled the plug on that#which would be a uniquely shitty thing for him to do#but i'm just like#do i want to work with this guy for another 4.5 years??#constantly seeking approval and constantly being told that I'm not up to scratch??#or should i just say fuckit and apply for professorships in the UK/US after extending my postdoc another year?#basically anywhere that isn't with this guy?#i should really milk him for glory#bc he's a golden boy#fuck i hate this

3 notes

·

View notes