researching queer women and rural space/ can be found knitting, baking, and thinking about Mary Oliver. hopeful academic in the making. autistic n overwhelmed easily

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

From No More Invisible Women Exhibition - Lesbian Herstory Archives both 1986-1997 "Women Get AIDS Too" poster by ACT UP Maxine Wolfe's "A BRIEF (and not complete) History of Women Focused Actions by ACT UP"

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Tessa Boffin, One of the Leading Lesbian Artists of the AIDS Crisis, Vanished From History

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

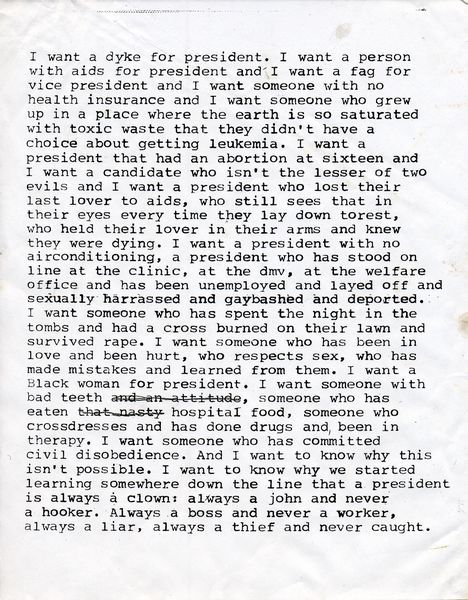

Zoe Leonard - 'I Want a President' (1992)

“I want a dyke for president…” form the opening lines for the battalion of critical incisiveness and queer radical spirit that is Zoe Leonard’s 1992 piece ‘I Want a President’. Surging forth into the American public realm following the fatal negligence of Reagan’s administration during the AIDS epidemic and the next presidential election run-up, ‘I Want A President’ dared to interrogate the fundamental denial of marginalised bodies, minds and experiences in the political arena. Constituting a poignant position in the broader visual languages of AIDS activism and queer resistance, ‘I Want A President’ broke ground in inspiring and furthering a critical modality of hope. Its impassioned sentences at once demand empathy and humanity from authoritative figures. Leonard’s statements queer the metrics of power that vehemently deny those outside of cis-heteropatriarchal society by providing currency in promoting otherwise silenced voices, and reestablishing their lived experiences as ethically fundamental in the articulation and implementation of policies that account for real citizens.

Functioning as a key catalyst for ‘I Want A President’, Leonard was inspired by the dynamism of fellow lesbian poet and artist Eileen Myles’ presidential bid in the 1991-1992 presidential election, alongside Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Ross Perot. Myles herself charged up by Bush’s lamentations of “the politically correct” (which implied an intended diminution of the voices of women, people of colour and LGBTQ+ critiquing hegemonic political assertions) in his commencement address galvanised an intellectual juncture that scrutinised the supposed impossibility of an openly female, openly queer president in the mainstream American consciousness. Acting in symbiosis to Myles’ work and presidential candidacy, Leonard was (and remains) a prominent and active member of queer activist collectives like Fierce Pussy, and her political praxis and astute artistic sensibilities informed the dissemination and distribution of ‘I Want A President’. Formerly intended to be a statement for an underground LGBTQ+ publication, the piece was printed as a Xerox document and circulated amongst Leonard’s friends, wider queer social circles and activist cohorts. It rapidly rumbled outwards into the wider public space, levying a challenge to the unfeeling political elite through progressive prose that illuminated the standpoints of those most denigrated in American ideology and dogma.

Spanning experiences of targeted violence, poverty, and disenfranchisement, the rhythmic structure of ‘I Want A President’ is arresting in its unflinching engagement with state-enabled trauma interwoven with empathic sentences expressing solidarity with those who continue to survive despite the odds. Grappling with legacies of lethal indifference in institutional engagement with the AIDS crisis, environmental damage bolstered by social inequalities, and sustained acts of gender-motivated attacks, Leonard’s calls and aspirations for a feeling, loving and reflexive leader remain tantamount in the contemporary era. The concluding lines “Always a boss and never a worker, always a liar, always a thief and never caught” is deeply evocative as a searing indictment against acts of blatant corruption and incitement of destructive community tensions by political elites able to evade culpability through immense social privileges. ‘I Want A President’ and its power lies in its calibration of empathy as a lightning rod for action, to make the yearning for difference not a mawkish instinct, but a place of generative resistance against political systems that seek to elicit apathy from sustained deprecation of those who fall outside of the power lines on the basis of race, gender, sexuality, class, ability and beyond.

‘I Want A President’ continues to have vibrant reverberations in contemporary political and queer counterculture. In 2016, it was erected under Manhattan’s High Line, a New York park built upon a disused elevated railway, proclaiming its moving and robust prose to a new public audience in the run-up to the 2016 election which devastatingly saw in the presidency of Donald Trump, reminding us all too much of what ‘I Want A President’ advocates against. Leonard’s powerful work continues to garner creative inspiration amongst queer artists, notably being read by queer rapper and artist Mykki Blanco, directed as part of a film by Adinah Dancyger in 2016, providing a reading that was passionate, imbued with immense political frustration that made its words all the more visceral in the face of Trump’s eventual inauguration. In 2018, the piece was reprinted with 100 copies and distributed in aid of the Treatment Action Group, a community-based think tank producing bold, advancing research into AIDS/HIV and other conditions in the pursuit of LGBTQ+, gender and racial liberation. The timelessness and transience of ‘I Want A President’ is made clear in its sustained relevance in the fluctuations in the national political milieu, demonstrating its significance as a queer cultural artefact that inspires fights for justice across multiple social intersections.

Leonard continues to enjoy a lustrous artistic career, and is now represented by the Hauser & Wirth gallery, where ‘I Want A President’ was celebrated and honoured for its cultural impact and staying power. Translating the piece’s deep insights and challenges against discriminatory political dominance in the British context, one can foster ‘I Want A President’ in expressing their disavowal of political acts devoid of empathy and basic human respect. Namely the state hatred of trans and genderqueer people in the name of political point-scoring, the loathsome class stigmatisation of current prime minister Rishi Sunak in his boasting of defunding what he deemed ‘deprived’ urban areas and the skyrocketing levels of financial precarity and homelessness under a fractious economic system. Leonard’s ruminations and desires in ‘I Want A President’ remain emblematic of the potency of queer activism and eternally vital, in demanding better representation, for politicians that care, that feel, that emote, that dare to think holistically beyond the sinister motivator of unbridled capitalistic power.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sapphic Women And The AIDS Crisis

(Content Warnings: Discussions of HIV/AIDS and the AIDS Epidemic, medical references, references to blood including a photo of someone giving blood, discussions of homophobia and transphobia)

Often discussions of the AIDS Epidemic are centered on gay men (particularly white gay men) and while there’s been more recognition for our POC and trans brothers and sisters who suffered and died during the epidemic I think it’s important to discuss those who helped. Today we’ll be talking about one of the most important groups to help those fighting HIV/AIDS: lesbians and the WLW community. I’ll include photos throughout as well.

Giving Blood

People infected with HIV/AIDS often required blood transfusions, including often times multiple transfusions over a long period due to persistent severe anemia. However due to the rampant spread of HIV, the fact that many people were not getting tested (or were unable to be tested), homophobia, transphobia, and early on an inability to test donated blood for HIV/AIDS gay men and transgender individuals were disallowed from donating blood. This was an extremely difficult situation for many queer people as they were left unable to help their friends, lovers, partners, and chosen family members. Additionally many cishet Americans did not want to donate blood only for it to be received by gay and trans individuals (as well as drug users). Enter:

The Blood Sisters

(Photo Description: a colour photo of a group of women standing around a blue sign. The sign says “Welcome Blood Sisters” and has a dark red heart with red beams around it. There are 5 women in front of the sign, 2 on either side, and one leaning of the top. The women range in age from approximately mid 20’s to 60+. They are all smiling)

The Blood Sisters were an organization of Sapphic women (often self identified lesbians) who came together in order to donate blood and hold blood drives, predominantly targeting lesbians and Sapphic communities, in order to help their community. The Blood Sisters organization was in San Diego however many other similar groups got together in order to donate blood and organize blood drives for those with HIV/AIDS. Because lesbians were considered to be a very low risk group in the spread of HIV/AIDS, and for some time it was believed they couldn’t spread it at all (more on that later), they were still allowed to donate blood. While these groups did face adversity they worked extremely hard to help the people in their communities struggling through the epidemic.

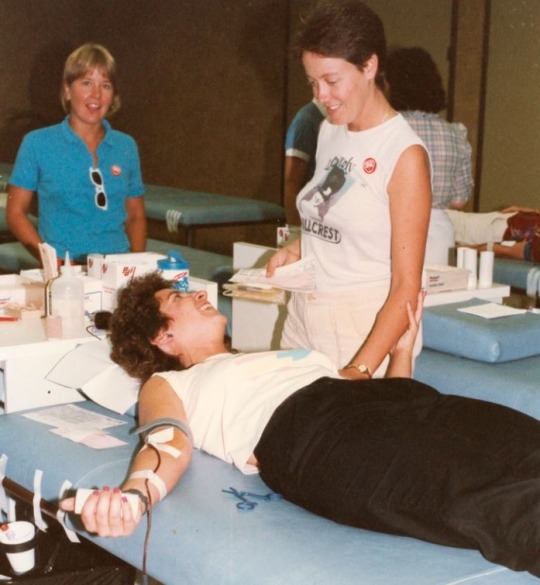

Photo of Lesbian Giving Blood

(Image Description: A colour photo of a woman lying on a medical table giving blood. She is being attended to by another woman who’s face can’t be seen. She has a tourniquet around her arm and she’s looking up at the other figure with a big smile. She has dark brown curly hair and is wearing dark high waisted pants and a white shirt with an unknown graphic. There are medical supplies in the background behind her head)

This photo was taken at one such lesbian blood drive.

Lesbian Doctors, Nurses, and Medical Professionals

Unfortunately I don’t have any pictures to supplement this section.

One other way that lesbians and other sapphic women helped those suffering with HIV/AIDS was by providing medical care. Many doctors, nurses, and other medical professionals, as well as those in the death care industry, would not provide care to those affected with the virus. While this was in part due to lack of understanding about how the virus spread in the early days of the epidemic, the effect that homophobia and transphobia had on this problem can not be overstated. Many queer people who were infected could not receive adequate medical care and treatment because of this.

However, lesbians and sapphic women once again stepped in. Many lesbians who worked in the medical field worked long and hard hours to provide care to those who were infected. It is a near certainty that some sapphic women likely even entered the medical field in order to help those affected by the virus. While they may still have been fearful they were committed to helping the people in their community who were most heavily affected.

Finally for today we’re going to discuss:

Preventing the Spread in Lesbian Communities

For quite a while it was believed that lesbians could not catch nor transmit HIV/AIDS however, it became apparent that while they were a very low risk group there still wasn’t no risk. Because of this many lesbians dedicated themselves to providing education for other WLW. This spawned a new phrase as well.

“Low Risk Isn’t No Risk” Leaflet (1992)

(Image description: a leaflet with the header “Low Risk Isn’t No Risk” at the top. At the bottom it says “Lesbians: HIV and Safer Sex” in block letters. There is a cartoon of two women sitting at a table with their legs intertwined, one is a white women leaning back with her arms behind her head. She is sticking her tongue out. Her shirt reads “ Had the fantasy, got the girl, read the leaflet”. The other woman is a black woman, she had textured hair and her face is shaded in to indicate she’s blushing. She has a flustered expression and has a text bubble which reads “Funny isn’t it- how talking about doing it can be so much naughtier than actually doing it?!” Beside the cartoon are three sets of texts indicating the material inside which say “How do lesbians get HIV?” “What if you think you’ve been at risk?” And “What is lesbian safer sex?” Beneath that is a logo for the organization which published the leaflet, Switchboard, it is a black and pink anarchist flag which has the organization’s name and a phono number)

Looking at the history of the AIDS crisis can be depressing and difficult but it’s important we remember both those who suffered and died as well as those who helped bear that weight. Lesbians, WLW, and Sapphics provided many great services to help prevent the spread and help those who had it. Remember: we have always been here, we always will be here, and we will always lift each other up. You are important and you belong here. 🩷❤️🧡💛💚🩵💙💜

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

excerpt from the queer nation manifesto published by act up ny in june, 1990

407 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Vincent Gagliostro Enjoy AZT (ACT UP), 1989 - 1991

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Moral Majority, 1983.

“Homosexual diseases threaten American families.”

My antitheism wasn’t taught by someone. I was conditioned from a young age to hate religion.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The first safe-sex poster in response to the AIDs Epidemic, 1983

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Essex Hemphill, from Ceremonies: Prose and Poetry.

In the 1980s, the urgency of queerness shifted from visibility to survival. The quotation in the title of this series is spoken by poet Essex Hemphill in Marlon Riggs’s Tongues Untied. Hemphill highlights the newfound danger of being queer in the age of AIDS: “Now we think as we fuck. This nut might kill. This kiss could turn to stone.”

Screen Slate, Now We Think as We Fuck: Queer Liberation to Activism

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

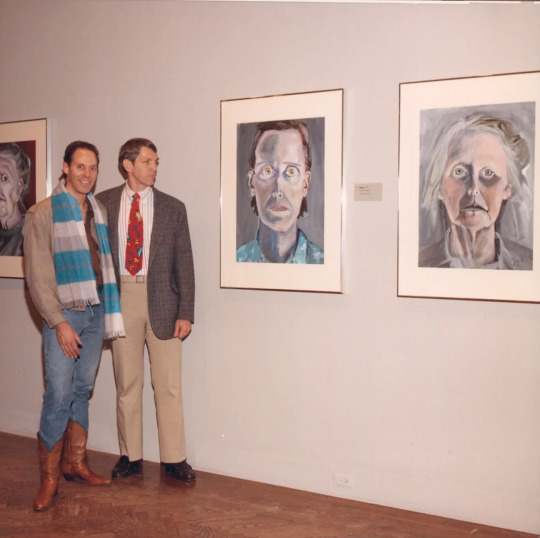

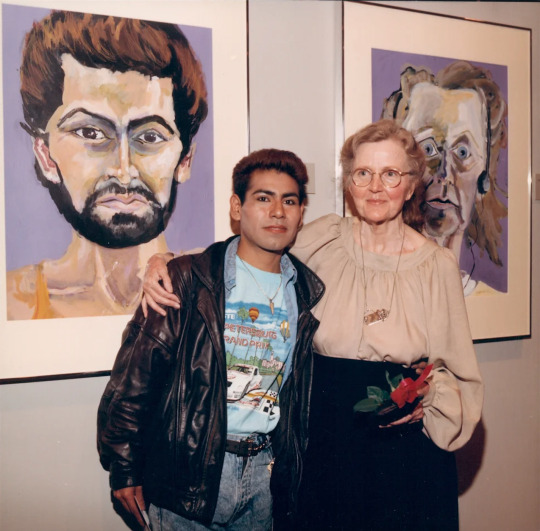

Artist Jackie Kirk with the subjects of her one-woman show, The Face of AIDS, that showed at the Legion of Honor Museum in San Francisco in 1991.

Virtually unknown at the time, she was among the first to artistically address the AIDS crisis, specifically in the Bay Area.

“What made the series unique is that Kirk painted a self-portrait after each time she painted a dying AIDS victim. They hung side by side in the gallery to reflect what she felt while staring into the eyes of a dying man.”

“Perhaps some people may approach this show with fear,” she wrote in her artist’s statement for the historic show. “They may think it is about death. It is not. I am painting courage and strength. It is, above all, about life.”

Jackie painted and created prolifically throughout her life; she passed away on June 25, 2021. (credit) (credit)

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

“I hope the nurse is sexy”

A queer icon i find people don’t talk about enough is Gia Carangi, this is a page from her diary during her finally days in hospital as she was dying of aids in 1986.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

"I’ve spoken about this a lot — it was at the height of the AIDS epidemic, so, late ‘80s. It was a terrible time for all of us. We were watching our friends die. The women’s community was sort of having to be strong and develop a voice out of that grief. We were really partying hard and having to demonstrate constantly. One of the reasons I was interested in photographing sex was, for one thing, no one ever talked about lesbian sex in the mainstream press. So we wanted to communicate and develop a language and educate each other. It was also a time when you had to graphically talk about sex. People were dying because they were having sex, and the government, the doctors — no one was telling us anything. We were learning new things every day, and we had to communicate it. It became necessary to be very graphic."

- Photographer Phyllis Christopher in an interview for her book Dark Room, 2022

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Puerto Rican photographer and Visual AIDS member Luis Carle took this photograph of Sylvia Rivera at the Saturday Rally before New York’s Gay Pride in 2000. Rivera is pictured with her partner Julia Murray, on the right, and by fellow activist Christina Hayworth, on the left. The placard at their feet reads “Respect TRANS, PEOPLE/MEN!,” stating Rivera’s lifelong cause of fighting for transgender civil rights.”

314 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who were the lesbian blood sisters?

“Suddenly, the hospitals were full of lesbians who were volunteering. Volunteering to go into those rooms and help my friends who were dying. I remember being so moved by them because gay men hadn’t been too kind to lesbians. We’d call them ‘fish’ and make fun of the butch dykes in the bars – and yet, there they were.”

In the 80s, the AIDS crisis was devastating the world of GLBT people - as the acronym read at the time. Gay men were banned from donating blood, which was desperately needed by patients dying from AIDS. The fear around HIV was so great that doctors and nurses refused to even enter the rooms of AIDS patients. These patients were often abandoned by their families in their dying days. There was a crisis was in the GLBT community, and so lesbians stepped in.

Lesbians organized blood drives in order to give blood to AIDS patients who desperately needed it. These blood drives attracted dozens, if not hundreds of lesbians at a time who all donated their blood. They called themselves the Blood Sisters, and they organized regular blood drives for at least 4 years. HIV patients needed frequent blood transfusions due to anemia induced from the virus, and so lesbians provided this blood.

In addition to blood drives, lesbians also took place as physical caretakers for gay men with AIDS, who were often abandoned by their families and even nursing staff who refused to go into their rooms. Lesbians held hands, fed, and took care of them.

In order to honor the efforts of lesbians during the AIDS crisis, the GLBT acronym was changed to LGBT, with lesbians deliberately at the front. Lesbians were a crucial part of the fight against AIDS, and this change would immortalize it in our community.

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

Penguin Classics was so insane for this cover. Didn't know they had it in them

13K notes

·

View notes