Sports Marketing Expertise. Consulting. Sponsorship. Events. Cycling. Football.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Knights in White Lycra

Words by Susan Burton

Why a group of foreigners bicycle to Fukushima every year – and what this says about charitable giving in Japan

The Knights ride out from Tokyo on the Friday evening bullet train, their bicycles dismantled and stowed in the obligatory rinko carry-on bags. They overnight in Takasaki city in Gunma Prefecture and the following morning they rise early to begin their quest – to ride 500 kilometres in four days to the Aiikuen Children’s Home in Fukushima prefecture and to raise money for the 72 children who live there.

In the peloton this year there are 42 riders from 14 different countries, ranging in age from 23 to 63. Twenty-six are attempting the ride for the first time. They are grouped together in seven teams of six, by experience, ability and willingness to stop for lunch. Each group is led by an able, veteran Knight.

Rob Williams (53, works in finance) is the Knights’ spiritual leader. In 2012, he and a group of fellow British expatriates were slumped disconsolately in the Hobgoblin pub in Tokyo staring at their beer guts. They concluded that they either needed to stop drinking or take up some form of exercise. They chose cycling because, “Brits are good at sport that involves sitting down.” There was also a more serious side to their quest. Following the Great East Japan Earthquake and nuclear disaster in March 2011, several of them had made repeated trips into the disaster area delivering emergency aid and public donations. But a year on, many places still lacked even basic necessities. One of these was Minamisoma, a city 25 kilometres north of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. Minamisoma was partially destroyed by the tsunami and most of the surviving residents were forced to relocate outside the 30-kilometre mandated radiation evacuation zone. In April 2012, when the zone was reduced to 20 kilometres, some residents had been allowed to return but many still had no electricity, running water or medical facilities.

That evening in the Hobgoblin pub, Rob and his friends decided they would cycle to Minamisoma to raise money to supply the residents of the city’s temporary accommodation with food and drinking water. Later in a karaoke bar someone stood up and sang the Moody Blues song, and the Knights in White Lycra (KIWL) were born. Their motto: get fit and give back.

Rob is also one of the ride’s team leaders this year. His team are strictly A to B cyclists, speeding to their destination in the shortest possible time. For lunch he allows them eight minutes to grab rice balls and Pocari Sweat drinks from the local convenience store.

Andy Abbey’s group prefer to stop for a sit-down lunch at a café or roadside noodle bar. Andy (British, 47, works in management consultancy) joined the Knights in its second year. Hours after the earthquake, a Facebook page called Foreigner Volunteers (now Foreign Volunteers Japan) appeared calling for contributions and helpers. Their first donation was a case of baked beans. When they had filled six two-tonne trucks, Andy and several other foreigners drove north. Recalls Andy, “Everything was just flat. It was terrifying.” The tsunami had swept away houses, cars and people up to 5 kilometres inland and 200 kilometres all the way up the east coast of Japan. Compounding the catastrophe was the nuclear radiation which was spewing from three exploded reactors and spreading unchecked on the spring winds and coastal currents. “It was very obvious that this was an unmanageable situation,” says Andy. Some foreigners went north only once, too traumatised by what they had seen to go back. Andy made repeated trips to the disaster areas. But he wanted to do more. He’s now a member of the KIWL committee.

Miho Inosaki (Malaysian-Japanese, works in public relations) is in Andy’s group. At 23, she is the youngest and least experienced rider and one of only five women in the peloton. She first encountered the Knights when she was tasked by her company Custom Media, one of the Knights’ sponsors, with filming their annual promotional video. Before becoming a ‘Knightess’, she had never cycled before and she averages one crash every third time she gets in the saddle. Within five minutes of picking up her new bicycle for this year’s ride she collided with a motorcycle. (During the ride, she somersaults over her handlebars and hits her head on a fence post.)

Egon Boettcher (New Zealander, 48, works in banking) leads another group and plans the Knight’s route, a difficult task due to Japan’s mountainous terrain and the fact that the ride takes place during the rainy season. Japan also has the world’s highest incidence of earthquakes, but the Knights have been fortunate. Earthquakes tend to strike in areas Egon has just left. This year, a magnitude 6 rattles Niigata two days after the Knights’ departure.

In previous years, the Knights had started their quest in Nihonbashi in central Tokyo but with heavily congested streets and numerous traffic lights it took more than three hours to clear the metropolis. Now they take the train and begin in another prefecture. This also enables them to vary the journey every year and to make it a challenge worth sponsoring. Tokyo is only 300 kilometres from the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, a distance that has been imprinted on every Tokyo resident’s mind since the plant’s meltdown. (By comparison, Chernobyl is over 2,000 kilometres from London.)

On the first day, the Knights cycle from Takasaki to Yuzawa in Niigata prefecture, a distance of 55 kilometres in 27-degree Celsius heat under a sun unobstructed by a single cloud. The journey takes them through the Japanese countryside in early summer, past flooded rice fields sprouting green shoots and to a height of 1,200 metres, in sight of mountains from which the snow has yet to melt.

They spend the first night in the town of Yuzawa, in a mountainous region of Niigata prefecture known as ‘snow country’. Their lodgings, a resort called Twin Towers, is a complex of privately-owned apartments developed during the economic boom in the 1980s. More than two decades into an economic recession, many of the owners are unable to sell and now rent out the rooms to cover exorbitant maintenance charges. There are few guests in green season. Andy appears to have the 11th floor to himself. Egon rattles round a duplex penthouse that he learns was refurbished for the Emperor and Empress during the 1998 winter Olympics in nearby Nagano (but they never stayed there). “We never saw a soul who wasn’t with us,” says Egon. “It was like the Shining.”

On the second day, they pedal further north to Niigata city on the Sea of Japan along routes lined with lush spring greenery and across wide bridges spanning streams that will swell into torrents in a matter of hours. With the rainy season approaching, a searing heat reflects off the tarmacked roads and a thick, stifling humidity envelops the riders.

Rainy season arrives on the morning of the third day, bringing 50-kmh head and cross winds. Three riders are blown off their bikes on the 150-kilometre journey to Aizu Wakamatsu, where the riders ease their aching limbs in the steaming onsen (volcanic hot spring). In case of accidents, injuries and punctures, the riders are followed by two support cars. Padded cycle shorts and ‘bum butter’ are essential on the road. But a soak in a hot spring eases the muscles at the end of the day. And that’s one good thing about having so few women on the ride, notes Miho. There’s always plenty of room in the women’s onsen.

On the fourth and final day, the winds have blown themselves out but the rain continues to trickle down the backs of windcheaters and seep into microfibre shoes. The morning begins with a long climb to a plateau on which sits Lake Inawashiro, the fourth-largest lake in Japan, also known as the Heavenly Mirror Lake because of the glass-like clearness of the water. The sun reappears just as the riders reach the Aiikuen Children’s Home which is situated south of Fukushima city and, gallingly for the exhausted riders, at the summit of one of the ride’s steepest hills. As they round the final bend, the excited children are waiting to greet them, waving flags of the Knights’ home countries and stretching out their hands for high fives. “It was just a wonderful moment,” says Miho later. “Just this overwhelming feeling of emotion where you went, ‘Oh my god, that’s why we do it.’” The riders dismount and the children, aged from 2 to 18, rush up. They want to know all about the Knights’ road bicycles. One little boy tries on Andy’s cycling helmet. “He decided I was his best friend and would show me the children’s home,” Andy recalls. The riders are led by the children into the gymnasium where they sit cross-legged on the floor to listen to a speech of thanks.

Aiikuen was founded in 1893 by Uryū Iwako (1829-1897), an orphaned daughter from a merchant family who dedicated her life to the improvement of living conditions for ordinary people. Situated 49 kilometres away from Daiichi, the orphanage is outside the evacuation zone. But because it stands on a hill facing the plant, when the reactors blew, its seven hectares of thickly-forested grounds – sports field, campsite and lawn – were coated in caesium-137. The prefectural government paid to have Aiikuen cleaned, hosing down the modern concrete buildings, removing grass and chopping down trees. But hotspots remained and for several years after the disaster Aiikuen staff (like many parents in the Tohoku region) limited the children’s outdoor playtime. They also tested food for contamination and regularly checked the children’s health. The immediate danger may have passed but Aiikuen still needs more support, which the government is slow to provide.

Nationwide, only ten per cent of approximately 30,000 children in care are orphans. The rest have been removed from neglected or abusive homes or given up by families who are unable to care for them financially. Fostering and adoption remain rare in Japan because parents must give legal permission for their child to be cared for by someone else and for cultural reasons – predominantly loss of face – they are unlikely to agree to this. Adoption is registered on the koseki (the family register) which is a publicly available document, and the stigma of having an adoption in the family bloodline (suggesting an unplanned pregnancy or a lack of financial stability) can affect job and marriage prospects. Less than ten per cent of children in welfare are fostered or adopted. Most remain within the welfare system long-term (just under half live in children’s homes for more than five years), sometimes with little or no parental contact. They are termed ‘throwaway children’, trapped in a legal limbo until they must leave at 17 or 18.

The attitude of some Japanese towards marginalised and disadvantaged groups is not always sympathetic, and the needs of children in care homes is not an issue that many Japanese wish to look at too closely. Says Andy, “I think there’s a blanket assumption here that the government takes care of everything. That’s good in some respects because generally the government kind of does but when something goes wrong – and the Tohoku earthquake was a perfect example – the government literally couldn’t take care of everything. No government could take care of that. It was impossible.” This is why KIWL has focused its money-raising efforts on children’s charities, in particular grassroots organisations for whom even a small amount of money can make a big difference.

In the gymnasium, the children present the Knights with certificates of appreciation printed by Aiikuen’s Digital Citizenship Club on its laser printer. With little or no parental support, a university education is impossible for young people coming out of the care system and they risk falling into low level work in factories or the sex industry. One goal of Aiikuen is to educate the children in skills that may enable them to find fulfilling jobs when they leave, particularly in the technology industry. During the ceremony, word arrives that the Knights’ cycle ride has raised just over ten million Yen (£75,000) for YouMeWe, the charity which supports the home. It will help to pay for more computing equipment and training in digital skills such as coding and video editing.

Most of the ten million Yen comes from corporate sponsorship. The Knights’ major sponsors are the international companies for which many of the riders work. This year, alongside the Knights’ logo (a plumed helmet and a shield depicting linked hands) there are 26 sponsor names on the riders’ jackets including Netflix, World Family, Land Rover, Boyd & Moore Executive Search and Allied Pickfords, companies which reflect the transient nature of expatriate life in Japan. In western countries, sponsoring someone to do a sporting challenge is a recognised way of raising money for charity. Egon’s first sponsored event at age 8 was cycling round and round a school track on a Raleigh bicycle. But in Japan there is no concept of the sponsored event. When Miho asked friends to sponsor her they were confused. “I got questions like, ‘Why would I pay you to do sports?’” In Japan, charitable giving more commonly takes the form of volunteering in the local community and doing chores – such as managing rubbish collections, street cleaning and watching over elderly residents – for your neighbourhood association. “It’s not that there’s no charitable spirit,” says Andy. “It’s just expressed in a different way.” 3/11 was a disaster on an unprecedented scale and many Japanese reacted immediately, collecting donations from friends and neighbours and forming residents’ groups to travel to the disaster area to provide volunteer labour. But paying foreigners to bicycle there was perplexing. Toru Akiyama, one of the five Japanese riders and at 63 the group’s oldest Knight, had to work hard for the money he raised from friends and colleagues. “He had to explain individually, this is what a sponsored event is,” says Miho. One result of the Fukushima disaster is that the number of charities seems to be increasing along with a shift in understanding about the many ways that donations can be raised. The 500-kilometre sponsored ride is not the only sporting challenge the Knights take on. There are marathons, pub quizzes, golf, futsal and even motorcycling. Once a year Andy organises a walk around the Imperial Palace and gives participants a KIWL t-shirt in return for a donation. “And for Japanese people that’s much more manageable psychologically than sponsoring Egon to ride 500 kilometres,” admits Rob.

In the days after the disaster, it was noticed by the Japanese media that some foreigners (known as ‘gaijin’ in Japanese) were attempting to leave, heading straight to Narita airport which was – ironically – marginally closer to the nuclear power plant. They were termed ‘flyjin’ and accused of ditching Japan in its time of need. In fact, just as many Japanese fled to southern parts of Japan where they had relatives. Most foreigners didn’t have that option. And many, like Andy and other future Knights, were driving in the opposite direction, right into the disaster area and risking their health, if not their lives, in the process. Andy says he never breached the 30-kilometre evacuation zone around the power plant. He drove around it. Nevertheless, he and the others were aware of the implications of a sudden rainfall or a change in the direction of the wind. Andy also took the iodine tablets the British embassy were offering. “He snorted them recreationally,” jokes Egon. The Knights are a good-humoured bunch but there is no denying the dangers present during those first weeks. While tourism (particularly foreign tourism) to the Tohoku region has since recovered, it should not be forgotten that the half-life of caesium-137 is 35 years. Wandering in the Aiikuen grounds after the ceremony the Knights come across a large radiation monitoring station. A nearby golf course appears deserted.

The Knights’ first sponsored ride, from Tokyo to Minamisoma in 2013, was abandoned when for the first time in ten years the region was hit by a blizzard. The highway was closed and several of the riders suffered hypothermic symptoms. Six of the original ten Knights returned two months later to finish the ride. That year they raised 2.7 million Yen (£20,000). Year on year they have doubled the number of riders and consequently the amount raised. In subsequent years, they have cycled to and on behalf of several different children’s charities in the Tohoku area. By riding to the charitable organisation the Knights can see first-hand where their money is going, which Rob observes has a greater impact on the riders. There are tears and, when the Knights move on to a new charity, some riders continue their support for a place they have visited. For two years, the Knights rode for Place to Grow (a charity supporting children and their families in Minamisanriku, a town that was 95 per cent destroyed by the tsunami). Andy and Egon continue to act as cycling Santas for them, delivering gifts to the children at Christmas. The Knights’ support for Mirai no Mori (a charity which offers American summer camps to disadvantaged children) has been maintained by BNP Paribas, a KIWL sponsor.

KIWL is a small group with a big impact. They have raised 62.3 million Yen (£469,000) since they first came together to “get fit and give back.” Says Miho, “The beautiful scenery, the challenge, the camaraderie, the drinking are all very nice bonuses but nothing really compares. Even the sensation of knowing that you’ve cycled 500 kilometres doesn’t come close to what you feel when you see all those kids look so excited to see you.” And Rob Williams has achieved another goal. ‘Fat Rob’ (as the others jokingly call him) has lost 10 kilogrammes since that drunken evening in the Hobgoblin.

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

tumblr

.@brumottistar does his stunts in the Dubai desert in “La Datcha” style by tinkoff_team http://bit.ly/1mvJzdQ

77 notes

·

View notes

Photo

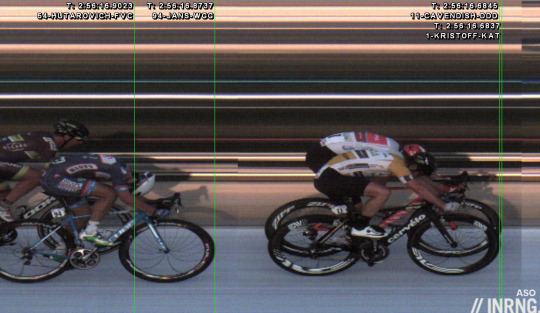

The photo finish of Stage 5 of the Tour of Qatar. Alexander Kristoff wins by 0.0008 of a second.

Photo thanks to ©QCF/Paumer.

45 notes

·

View notes

Photo

by @cycleexif: There’s a special @colnagoworld Master up on Cycle EXIF today. If you think the engraved @campagnolosrl Athena cranks are nice, check out the matching Delta brakes and @busymanbicycles leatherwork. Head to Cycle EXIF now for the full story. January 18, 2016 at 01:23PM http://bit.ly/1nfCJuf

140 notes

·

View notes

Video

tumblr

She’s a bit fresh!! -2.7°!! 😱😱#welcometofrance #facebalaklava #slurredspeech #toocoldtotalkproperly 😂🇫🇷❄️⛄️ @ash666 by nettieedmo http://ift.tt/1D1xmE0Vive le Vélo

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sky rider looks one way and drifts the other… while Ag2r’s Blel Kadri has his head down.

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#rockhopperipa with #bourbon and #southerncomfort and #maplewhiskey #beercocktail #gettingthere (at Jasper Brewing Co.)

0 notes

Photo

#stout #float obscenely good (at Jasper Brewing Co.)

0 notes

Photo

Hold on tight! Haha...roadie hands 1 hour after MTB ride. (at Jasper Source For Sports)

0 notes