#you grotesque monster of a dialogue machine

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I've really moved on from this conversation, but it is common knowledge that colonised people do not always have their native names because of colonisation.

You don't have to be a historian to know this.

This is a current political reality affecting the lives of millions.

It is incredibly worrying to me that I have to tell you this.

This is common knowledge, and you have been wilfully ignorant if you're unaware.

Your friend didn't ask a question. He asked how the fuck he could work with a black character with that surname and that he had to make her mixed-race because of it.

He wasn't spoken to like a sod. He was told that was an ignorant thing to say and to use some critical thought.

I did, in fact, explain it. For all the good that did.

I can't believe I have to say this but, for anyone else reading this: it's okay to tell people they are ignorant of ongoing global history. especially when that ignorance is harmful to colonised peoples.

I'm genuinely curious why as a fandom we decided that Mary is black.

Her surname is McDonald, how tf can I work with a black character named MCDONALD???

Now I have to make her mixed and not fully Ethiopian, and all of this is because of whoever though it's a smart move.

#eva out!#tonight#we drink tea and read fic#absolutely my last word on the matter#hoo boy#did not think i would need to debate this#tumblr#you grotesque monster of a dialogue machine

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

thoughts on little goody two shoes

took me a while to get around to it, but i finally finished watching a playthrough of this game and all the endings! i wouldn't say it's a game i would want to play for myself, but it's definitely one i would recommend to anyone with an interest in the genre

spoilers for the game below

positives!!

the game is... a lot less scary than i thought it would be? even with the all the sacrifices and monsters everywhere, aside from some blood, there was nothing too grotesque. no jumpscares either! just running from creatures ^_^

honestly, for all the creepy shit going on, the game is just pretty wholesome? the reason elise does everything really isn't to get rich - she wants love and respect. she mentions that she feels worse after her grandmother passed, and wants to leave the village where she gets pushed around all the time. she just wants to be happy.

the conflict between ozzy (+ his followers) and walpurga is just really cool to me. i like the thought of two beings fighting over a person, and the specific situation this game presents is interesting. ozzy made elise for holle, but in walpurga's grove. her desperation to have a child makes her obsessed with claiming elise as her own, causing a conflict. not to mention ozzy's followers! i just love infighting between antagonists for some reason.

the artstyles are all so pretty! and they all blend together so seamlessly?? the 90s sprites for the dialogue, the pixel chibis for the gameplay, and the more detailed/painted look for the backgrounds!

the music!! it's all so good, and i just love the female vocals even if they're going la la la or ba ba ba ba! i've rewatched elise and rozenmarine's cutscenes multiple times now, and even though i muted the playthrough at times bc the bgm and sound effects were too creepy for me, i always turned it back on whenever a golden girl appeared. the mysterious yet calming music that plays whenever a girl speaks is definitely my favorite track!

i LOVE the minigames being structured like arcade machines. just. beloved <3

negatives...

FUCK that part of the thursday witching hour where you have to play in complete darkness. just fuck off. i know i sound dramatic but this is a "what were the devs thinking" bit for me. no one on earth would want to play that.

some comments of the playthrough said that the puzzles were a nightmare, especially for first time players. and i have to agree to some extent. all the puzzles that take place in the crow's section (the yellow castle/wheat field/maze) just feel exhausting, mainly the shaky bird trees and the saving apfel quest. at times it feels like a "you have to take damage to continue" segment

muffy :/ she's adorable, but she's only used for the suspicion mechanic and stealing your food. maybe it was just the playthough i watched, but food can be pretty costly along with buying regen supplies and oil. maybe she could've vouched for elise in a tense scene if the player helps her! that would've felt nice. also, the joke about elise constantly calling her the wrong name is just... really lazy humor

when it comes with the endings with the girlfriends (1-3 and 5-7), despite how the happy ones are very different, i don't feel like replaying the game to get them is worth it. honestly, the ending that intrigued me the most is ending 4 with father hans because it's so unique

as i said above, the game wouldn't be something that i would want to play for myself, but i would definitely share with others. i'm tempted to check out the original pocket mirror and the remake now!

#waba talk#games#lgts#OH#ALSO#JUST REMEMBERED#why does elise call her “rosmarine”#the voicelines don't even match up#was this mentioned somewhere. am i dumb#waba thoughts

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

sunflower (im on desktop lol)

Going to talk about some indie/lesser known games that I’ve played recently and think people should know about.

Probably the most well known is Hollow Knight. It is about a trying to save a fallen kingdom as a bug. Lots of cool lore and exploring is a must if you want to learn all the secrets. Definitely a game that will test you with its battles but definitely worth it!

Gris is by far one of the prettiest games I have seen. It is about the stages of grief with each one being represented by a color. There are achievements (which I love) which offer people an incentive to do more than just progress the story. Also no dialogue but a bit of singing.

Little Nightmares is probably another one that is fairly well known. It is a horror game were you play as a little girl trying to escape a floating island filled with deformed humans. There are some pretty grotesque visuals but it has such a cool atmosphere.

Iris Fall is a game where you use shadows and light to solve puzzles. There are over 20 puzzles that make up the whole game so the game length can vary based on how good your are at solving puzzles. This game really commits to the visuals. This is also another game with no dialogue so you have to figure out the story on your own.

Gleamlight is a short platformer where you play as a being made of stained glass. You fight monsters made of machines. One interesting thing is the health bars. You can steal health every time you hit a monster but they can also steal health back. This game is deceptively short but that’s not the whole game. So if you do decide to play it use a guide.

The most recent game I’ve finished. The Last Campfire is a puzzle game to help other lost embers pass on. There is voice acting and a variety of puzzles. Also the story is very realistic as you meet people who you will refuse your help as you try to bring them back from despair.

I love World’s End Club! But I don’t think it is for everyone. It is sidescrolling platformer for certain stages and visual novel for the rest. A lot happens in this game. There is a death game followed by the characters finding out about the end of the world. There are several instances of brainwashing. The main characters get superpowers. There’s a cult. Plus so much more. All the characters are great and it has full voice acting. It has a branching story too (even though there a limited number of choices). I haven’t finished it yet but it is so great.

This game is literally so cute!!!! It is a sidescrolling platformer interspersed with storybook scenes that explain the story. The Liar Princess is a wolf who accidentally blinds the Prince and goes to the Forest Witch to become a human in order to help the Prince get his sight back. She is the one that the player controls and is able to switch between her princess form and her wolf form. She guides the Blind Prince through the forest to the Witch. And she does this by holding his hand. She also collects flowers and gives them to the prince throughout their travels. This game also has achievements (a fair amount of them actually). The visuals are all this sketchy design which gives it a unique storybook feel. I love it.

Thanks for the ask!!

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Secret Diary Reviews... Crimes of the Future!

So, David Cronenberg must be old as fuck by now, but he hasn’t missed a beat. I just finished watching Crimes of the Future, his latest weird-ass masterwork and its… subtly brilliant. But before I explain why, I should probably explain who Cronenberg is for the benefit of the wet-behind-the-ears whipper-snappers among you who missed Videodrome and his other early efforts. To whit: Cronenberg is a master of body horror, a very specific subgenre that focuses on all the terrifying ways the human body can be distorted or spontaneously betray the person riding around in it. He’s known for creating horrifying, fleshly realisations of our most grotesquely biological nightmares and parading them on-screen so that we can all be grossed out and frightened by them. His work, while schlocky, is primal and taps into our innate fear of decay and bodily revolt. It’s often melded with the politics of the year or decade in which the film is made, too, so that the body becomes a metaphor for our societal condition. And it does all this without being a load of pretentious wank.

And then, there’s Crimes of the Future, which is set up like a body horror film, but isn’t one. It’s got all the hallmarks of body-horror. People performing surgeries recreationally? Check. Gooey close-ups of human innards being toyed with in ways you’d prefer not to look at? Check. Sexual perversions centred on cutting into the human body being presented in the most disturbingly sensuous way possible? Big fucking check! Actually, I don’t recommend having this film playing on your laptop while other people are in the room trying to do their own thing (like I did, because I’m an idiot) as there are MULTIPLE scenes of naked, blood-covered men and women taking pleasure in having their bodies cut up and rearranged. It’s not the kind of imagery you want to inflict on your loved ones if they happen to walk past or glance screenwards at the wrong moment. But I digress. Crimes of the Future goes out of its way to look like a body horror… and then isn’t.

So what the fuck is it? Well, that’s not an easy question to answer with spoiling anything, but I’ll do my best. Our central character is an artistically-inclined chappie named Tenser whose body keeps growing new, seemingly extraneous organs that he really doesn’t want, referring to them as cancers and the product of a genetic syndrome. Throughout the course of the film, he encounters people who are growing new organs and have actively embraced them; people who have had surgery to change their bodies and both governmental and corporate organisations that want to control or limit the creation of new bodily systems because they believe that humanity should remain unchanged. Ably assisted by his lovely surgical assistant, Caprice (yes, the name struck me as a little on-the-nose as well), Tenser navigates this world of conflicting interests and ultimately… changes his mind.

And that’s it- the crux of the film; the point on which it pivots. It’s not about the horrors of the human body, but about accepting. It’s not about fearing fleshly change but embracing it. All the elements are there for Tenser to become a monster or have to survive one, but he doesn’t. All the elements are there for him and Caprice to end up violently at odds with one another, all their weird fetish-sex turning to hate and violence, but by the end of the movie, it’s obvious that they’re very much in love and who the fuck cares if they use a living Giger-esque nightmare machine to explore each other’s bodies? They’re not hurting anyone… except each other, and they seem pretty into it.

In short, Crimes of the Future is a film about self-acceptance and about learning to live in harmony with one’s own body and its changes. Is it a perfect film? No. A lot of the dialogue is just David Cronenberg announcing to the world ‘OKAY! I HAVE SOME THOUGHTS ABOUT [INSERT SUBJECT HERE]!’ Plus, the film drops a few too many plot-threads that might have been interesting if they’d been allowed to somewhere. But, though imperfect, Crimes of the Future is one of the most scintillating and worthwhile cinematic experiences I’ve had in a while. What’s more, taken in conjunction with the rest of Cronenberg’s oeuvre, it shows a rather heart-warming trajectory. In his early films, Cronenberg was expressing a fear and disgust for the human body, suggesting a deep distrust of his own. But with Crimes of the Future, Cronenberg seems to have finally accepted the divergences and unpredictability of the human body in general and, perhaps, his own in particular. It’s a deeply personal work that represents the end of a long, internal struggle for the director. I recommend it.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is Teen Wolf Lovecraftian?

Is Teen Wolf Lovecraftian?

Yes, very much so.

Why?

To understand if Teen Wolf is a Lovecraftian horror we need to start by defining our terms and providing comparisons. Lovecraft stories directly made into movies as a whole are just bad, and most video games too. However, using Lovecraftian ideas and tropes creates a successful narrative in most cases.

Several things define the Lovecraftian horror experience.

Isolation both mentally and physically

Lack of character information which is replaced by character reaction.

Lack of information about the world in which the protagonist finds themselves with a penalty for discovering that information.

The revelation that that which was formerly known is now revealed to be unknown and the consequences thereof

Fear of the unknown, specifically the previously thought known

Body Horror, specifically bodily transformation, from which there is no reversal

The insignificance of the subject in regards to the whole

These look specifically vague and you can apply them around a lot, and people do, but you might also notice a lack of tentacles there.

So before we turn this on Teen Wolf let’s present an example that you can understand the points in question

John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982)

A group of men in an Antarctic station inadvertantly let something other into their base.

Interestingly the least Lovecraftian thing in “The Thing” is the thing itself, and wasn’t that a fun sentence to write.

The Americans [as opposed to the late Norwegians] are already at breaking point, isolation - caused by the weather, their close proximity to each other, boredom and exhaustion have taken their toll, they are a brush fire just waiting for a spark, and that spark is the thing. It is not the spark because it’s hunting them down, because that seems almost incidental in it’s desire to just survive and hide despite it’s otherness, it’s the fact that any of them could BE the thing. I’m going to start calling it the alien - it sounds less like I’ve forgotten the word. This will probably cause problems when I move on to Alien (1979) in a minute.

Combined with that Carpenter uses long empty tracking shots (a technique he used in Halloween [1978] ) which creates a voyeuristic feeling which removes the safety of the base. The way that it works matches “The Strangers” (2008) which removes the feeling of being safe in your own home. The rich white affluent suburb with it’s white clapboard houses and wide green open spaces is invaded by “the shape” as he is called the in the credits, and those shots, in which nothing happen, makes the space unknown and terrifying for it. It removes the illusion of safety.

We know almost nothing about the men in the base, we become invested in them not because of what they are but who, they are charming, funny, tired, and very realistic but it becomes hard to remember their names because those things are ultimately irrelevant. Combined with the discovery of the space ship those men are irrelevant, what they undergo is irrelevant, no one is on the other end of the radio, they will not be saved and their deaths serve no purpose. They and their experience doesn’t matter.

In Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979) does the same thing, a random ship encounters something vast and unknowable and is infected, the Xenomorph then picks off the crew for no other reason than to continue it’s own species, it doesn’t choose them for any other reason than they are there. The robot’s betrayal makes them even more meaningless, any ship that encountered alien life would do, it just happened to be that one.

The presence of the Xenomorph makes the ship unknown, it could be anywhere. At first they think it’s something small and don’t learn otherwise until face to face with it. They have to use technology they don’t quite understand and can’t really use to find it in their own safe space. A safe space surrounded on all sides by absence - space itself. All the things on the ship which previously gave them safety, the machines that allow them to exist on the ship, are now dark places for it to hide.

In Dario Argento’s Suspiria (1977) - the only film not to have aliens - Suzy goes to a place that is grotesquely beautiful and just happens to be in the next room to the girl who is investigating it, when that girl goes missing she looks for her and discovers the old witch and kills her to save her own life.

Yet Suspiria, which might be the most Lovecraftian film of them all, has no exposition, most of the characters aren’t introduced, and the movie is mostly experiential, maggots rain from the ceiling, but we don’t know why, the witches are killing the girls in the academy but we don’t know why, instead we have a lurid oversaturated nightmare of a narrative where the dance academy swerves from mundane to brightly lit Roger Corman-esque interior design fantasy. It is a building that if Ludwig II took acid he might design using only primary colours, art nouveau doors, blood red walls and corridors that seem to ooze menace without doing anything, overlaid with Goblin’s infamous soundtrack. Combined with that the actors filmed the dialogue in their own language and English was dubbed over so the characters are not really communicating.

Suspiria is as close to reading Lovecraft (without the racism) as it is possible to get. And it does also feature body horror when Sarah is resurrected by the witches to act as a weapon, despite her slit throat and the pins in her eyes. It is a nightmare on film.

It is also not a film you watch. It’s a film you experience. [The remake is good but very different and not so Lovecraftian, although most of the characters are played by Tilda Swinton, it’s really squinting are you Tilda Swinton too?]

So having given defintions and examples of what it is - does Teen Wolf fit.

Isolation both mentally and physically

It is impossible for the characters in the know to leave the town, and even if they do then they must return.

We see Scott try to leave twice, once in Motel California and again in Ghosted. Both times they enter a phantasmagoric town which is certainly not the outside world. Other characters are taken by the Wild Hunt. Derek Hale manages to leave, but only after “evolution”.

His trips to Mexico are also phantasmagoric in that it is hard to say that they are not dreams, the Calavera stronghold for example uses a lot of dream logic and wonky camera angles giving the idea that it’s not real. La Iglesia does this as well.

Within the town there are those who know and those who do not. Those who know flock together but have to keep their secret from those who don’t. So Scott doesn’t tell his mother until season 2, Stiles doesn’t tell his Father until 3b, Lydia is still trying to tell her mother in s5.

Characters unaware of the knowledge that others know are completely isolated, without anyone to go to, which usually ends in violence, often against themselves - the Chimera.

With as much as the main characters know it is clear that they know very little about the town, as shown by the family of wendigo who were part of the community.

2. Lack of character information which is replaced by character reaction.

We know almost nothing about any of the characters. We know how they react and how they interact, and how they change, but their histories are completely absent. This is as true of the main characters as it is the victims who only appear in one episode.

3. Lack of information about the world in which the protagonist finds themselves with a penalty for discovering that information.

People know nothing, research can present viable answers which are later proven wrong, characters guess in good faith and are wrong, characters lie, but ultimately they know very little about the world in which they’ve found themselves and those who do know often withhold or manipulate that information.

An easy example is Damnatio Memoriae in which Scott discovers what he believes to be the identity of the original Beast, a serial killer in France, who has nothing to do with the Beast at all. It’s a coincidence that the term has been applied. The knowledge is irrelevant and Scott is left with no more information about the Beast than he did at the start, then the person who does tell him, in Maid of Gevaudan, is Gerard and has every reason to lie, and that’s assuming his guess was correct.

The more characters know in Teen Wolf the more likely they are to end up in Eichen House, and Dr Fenris, in 6b, with the information he has, becomes a mass murderer.

4. The revelation that that which was formerly known is now revealed to be unknown and the consequences thereof

The town is a supernatural hotspot and the revelation of that is the entire plot. I think we can agree that that one certainly applies. Combined with that the use of “safe spaces” as battlegrounds, such as the school, the school bus, the sheriff’s station.

5. Fear of the unknown, specifically the previously thought known

Dr Fenris killed the monsters in his care, the Sheriff nearly has a nervous breakdown with the appearance of the chimera, the possession of Stiles and Scott’s reaction thereafter. These all very much apply, even Stiles fear when Scott attacks him in the locker room in pilot. The more people know the more scared they become.

Traditionally in horror the less people know the more they have to be scared of, but in Lovecraftian horror they know enough to fear it, but not much more, often the creature, by its very existence can induce fear (like the Anuk-Ite) because it is so outside the realms of what the human mind can comprehend.

6. Body Horror, specifically bodily transformation, from which there is no reversal

Werewolves. It is worth mentioning here however that there are anomalies in the transformations, almost all of the werewolves speak of pain during transformation, and Derek uses pain to help control it by overwhelming them with pain, but Scott does not. Just as the protagonist in “The Dunwich Horror” finds himself turned into a fishman there is an inevitability to the transformations in certain cases. Derek is on a path to his inevitable evolution. Scott’s natural evolution is subverted, this might be because he never transforms after his black eyed beast form in season 4. His fear of his transformation holds him back from his inevitable end form, yet there is no way he can be human again, no matter how much he wants it.

7. The insignificance of the subject in regards to the whole

Scott is not important because of who he is. He’s important because he happened to be the person in the wrong place at the wrong time. He is incidental to most of the story despite him being the focus character, the world doesn’t care about Scott McCall, it is interested in the True Alpha, but that could as easily be Chuck Norris. Scott isn’t even the true alpha by virtue but for reasons we do not know, Deucalion had no interest in it, Peter thought it was hilarious, Morell manipulated it to save her own life and Deaton worshipped it. Others use it as a target. When Scott says, “I’m a true alpha you don’t know what I’m capable of” it defines the character. Kincaid tells him he’s not as strong as a normal alpha. There are questions around his biting of Liam. Scott is not the Chosen One, he’s the one that was there and that’s ignoring his questionable behaviour and the very strong argument that he is a villain, and that his narrative was one of fallen messiah and not the hero’s journey.

Frodo was not the Chosen One, he was the guy who had the ring, and many of his successes are because of his party of companions, but Frodo’s quest, which he fails, is of world ending importance.

In Scott’s case, he again succeeds mostly because of his companions, though, unlike Frodo, he is unaware of this, he is not throwing the ring into Mount Doom to defeat Sauron, returning the ring to the jeweller because it needs resized, and might pick up some milk as well while he’s in the area.

So in conclusion is Teen Wolf Lovecraftian = yes

Does it fit the criteria laid out by works accepted to be Lovecraftian = yes

Does it follow the conventions of similar Lovecraftian works = yes

Is it the Lovecraftian conventions spread over such a large scope that cause so much dissatisfaction in the audience = yes

Almost every point in the list is something I’ve seen people complain about, we don’t know about this, we know nothing about that, that makes no sense, I think this episode would make more sense on hallucinogens etc

It is a well written Lovecraftian nightmare, it uses variant realities and isolation, suspicion and distrust well = but it tells us nothing, resolves very little and has a main character who could deliberately be replaced with a well meaning bag of sand.

But at least there were no tentacles.

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

120 Days of Overexposure - writing #7

About 120 Days of Sodom The famous title of the book written by 18th Century French writer Marquis De Sade refers to the events that took place in a four months period of time when four rich and noble libertines -lets say they are radical hedonists- locks themselves up in an isolated medieval type castle on top of a mountain surrounded by forests with a number of 36, mostly teenage victims of both genders and start performing their sadomasochist fantasies on them.

Now I haven’t read the whole book but I made some research on the time period and found out that the socio-political agenda -as it is an obvious statement- was more complicated than it looked. French Society and the common people of the time period in specific, rates as the highest society that knows how to read in Europe. But the interesting part is that the people were reading pornographic and comedic caricatures about the members of the Monarch and one other category that got the most attention was the erotic novels. Here it goes.

The Libertines are accompanied by four veteran prostitutes. They tell the stories of extreme sexual experiences they've been through with their former partners or customers in graphic detail and in a lustful way. These stories becomes the motivation point for the libertines to perform the same or worse sadomasochist acts on their victims. It's stated by the writer in the book, that the sensations produced by organs of hearing are the most erotic. Actually this is an interesting statement that I want to point out.

What is the nature of these most vile and suppressed desires that human beings possesses? Why they are needed ti be expressed in such savage and primitive ways? We as humankind developed ourselves parallel as we developed our civilizations thereby our culture and morals. But what are those leftovers on the plate that reflects our grotesque selves? Are we like some kind of steam machines that needs to be deflated time to time to work properly? These are the kind of questions wandering around in your head while reading the works of Marquis de Sade. When you look at the language he uses, you wonder how come this guy is any different than those erotic story writers on the adults sites of web? How come we see his name in every bookstore around the world on the shelf of "French Literature" and not necessarily "Erotic Fiction"? De Sade uses his paragraphs as a stop to hold and think what you've been exposed to in past pages of thirsty dialogue. No matter what you've thought or felt reading about the perverted actions of these libertines, you can always recall your intellectual and ethical self while reading the bedroom philosophy of De Sade.

Speaking of philosophy; I think we can agree on that if we properly introduce ourselves to the works of Marquis De Sade, we can easily discriminate his intellectual character from those only capable of providing enough blood pressure for their genitals and not their brains when it comes to subject of lust. I'd like to sympathize with the words of Slavoj Zizek. The Slovenian philosopher once said in an interview that he would like to live in a world where everyone doing whatever they want and living their life in an honest and authentic way. "Just be yourself but don't express yourself too much." He also stated."We are all monsters but I still do believe in proper manners." I'd like to finish with saying if we are talking about the works of one of the greatest controversial writers in history of literature, we should be thinking in the nature of self-judgment.

Can we be held responsible of our thoughts and desires as well as our actions? What is the red line between an innocent urge and deadliest sin? Will we be a mere listener of those prostitutes or become the ruthless torturers of our victims? How ca we overcome our handicapped nature through our human intelligence whilst accepting we're all animals? I dare you to think on those questions 'friendly reader' while reading the 120 Days of Sodom for the following pages are full of dreadful and unnerving events as amazing and exemplary they are. Just like life itself.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Disco Elysium (Review)

Gameplay (8/10) Monsters out, dialogues in

(+2) Innovative take on the RPG genre. The gameplay, skill tree, and level progression of DE is a very fresh take on the classic RPG formula. Instead of traditional combat where you reduce an enemy’s hit points to 0, you need to pass skill checks that are based on your invested skill levels. Instead of gaining exp and leveling up by fighting monsters in an action RPG, you converse with the citizens of Martinaise and interact with the objects scattered around the district. You gain skillpoints when you level up and you invest them in different areas in order to represent what kind of detective you want Harry to portray: The thinker, the psychic, the muscle, or the specialist. It doesn’t play like your standard RPG, but it is built on the same foundations of character customization (you can even dress up Harry in whatever way you want.)

(+1) Failure is part of the game. To my knowledge, you’re not gonna be able to max out all skills so you have to focus on one area of expertise and leave out the rest. If you play as a logic-based detective you’ll probably be on the bottom end when it comes to physical prowess and hence fail a lot of the physical-based tasks. This however doesn’t necessarily mean a game over, as the game gives you many avenues to tackle a problem, some even require you to fail to get the more desirable outcome.

(=) There’s a lot of reading. A LOT. Disco Elysium is basically a more interactive version of a visual novel so 90% of the gameplay would be reading the many dialogues thrown your way. It’s the core gameplay loop of DE and the extensive amount of reading might turn people off or bore the people already playing it, while enticing the hardcore readers to get into it more.

Story (8/10) A journey of redemption or downward spiral

(+2) Decide Harry’s fate. You hold in your hands how Harry will deal with his situation. Will he become sober or stay an alcoholic? Will he solve the case or fail horribly? Will he do drugs or remain clean? Will you sleep in the inn or out on the street? Will you even remember your own name or how you look like or will it disappear into oblivion? All these different options mean that every playthrough of DE will be a unique experience depending on how you built Harry and the choices you make during interactions. If you’re not careful (or if you’re just purposefully diabolical), Harry may meet one of the game’s many game over screens depicted as newspaper headlines, or you may not see one at all throughout your playthrough if you’re really careful.

(+1) Lieutenant Kitsuragi. Enough said. The straight man to your crazy antics, Lieutenant Kim Kitsuragi is the down-to-earth partner you need to keep you grounded when your mind floats to strange dimensions. He almost feels like a character being played by another player online. He is patient and understanding when it comes to dealing with Harry’s personal problems, but also knows when to be strict when Harry is going too far with his unorthodox methods.

(+1) Intricate world-building. The world is wonderfully laid out to the player through dialogues and environment design. You can see the extensive damage Martinaise has sustained and you can realize that it was a previous warzone even without asking any of the townsfolk. Conversations with different people reveal all the political struggles Martinaise underwent and the world beyond and how the pale is consuming everything. You can choose to know more about the world at large or just let it slip by you and go on with your investigation. Regardless of which you choose, you’ll still come across very obvious signs of political unrest, corruption, drug trade, and general poverty all over the district which tells you that this is not just the generic town littered with NPCs and interactions, this is a town inhabited and shaped by the people living in it.

(=) Heavy political undertones. As mentioned in the previous statement, there’s a lot of political unrest going on in Martinaise aside from the Union’s strike. If you’re like me and don’t care that much about heavy political jargon, you might find this piece of the game quite undesirable. Nevertheless, you can choose to opt out of most political conversations and avoid all the confusing words they throw around here and there.

(-1) Underwhelming resolution. The ending was very lackluster to say the least. It all culminates in a final showdown with your police investigation unit where you present everything you’ve done throughout the game and depending on how you acted Lieutenant Kitsuragi will vouch for your actions. There’s no resolution as the game just ends after the conversation without knowing how it all went down for the characters after they’ve reported the case to their respective superiors. Not even a cliffhanger hint of a sequel. Arguably, this might tie into one of the game’s themes of not having closure but as a player it didn’t leave the best impression on me.

Visuals (9/10) Flamboyantly grotesque

(+3) Magnificent artwork. The crowning glory of Disco Elysium is the artwork. The drab watercolor-like aesthetic of the game reflects the game’s colorful and creative world plastered with grim filters of reality. It’s something that I think cannot be achieved by going for a hyperrealistic look where things appear as close as possible to real life counterparts, but rather through the lens of a rough and distorted perspective of an alcoholic detective with an abundance of internal struggles. It reminds you that there’s beauty in destruction, and destruction in beauty; as alluded to by one of the quotes found in-game. On top of that, the portraits for the thoughts are overwhelming in a mesmerizing way. Similar to how you just can’t understand what’s going on in an intricate stained glass art, or the thick black strokes of the inkwork on a tarot card, there’s just so much going on and it’s a lot to take in but you still get captivated by the imagery. You can take any still from any moment in the game and present it as a renaissance painting and I’d believe you just because the game’s artwork is that wonderfully made. Truly a testament to the talent of this generation’s artists.

(+1) War-torn Martinaise. This district has lots of stories to tell without even having a mouth to speak. The way Martinaise is presented is very organic. You can still see bullet holes and mortar damage from the war fought over the district many years ago, old arcade machines from a forgotten time litter the establishments, entire buildings with abandoned equipment of their former establishments, and repurposed infrastructures. This wasn’t just built as a place the player has to explore during their playthrough, this was a place with history and has lived way before the player step foot within its bounds.

Audio (7/10) It’s all in the voice

(+2) Superb voice acting. The voice acting gives life to the characters in Martinaise and it comes in all shapes and sizes. Every character has at least one voiced line so you can have an idea of how they sound like. Some of the more important characters have more than one voiced line, which reiterates their importance in the overall narrative. The character’s personalities and idiosyncrasies come alive in the voice acting, from the way they say certain words and their inflections, letting you know that Martinaise is home to more than one group of people as a result of the district’s history.

Final Score (8) Excellent This is Disco, baby

Disco Elysium is more than just a game, it is art first, a visual novel second, and an RPG third. The game accomplishes something more than to entertain you for the few hours you’ll pick it up. It also attempts to educate you on political discourse and warn you on the adverse effects of drug and alcohol abuse, all while being enveloped by the game’s captivating art style. You’ll find yourself appreciating the scenery more than a few times while you scour Martinaise looking for any sort of lead that’ll help you with your case.

(1-2) Terrible (3-4) Bad (5) Average (6-7) Good (8-9) Excellent (10) Masterpiece

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

WILD ARMS 2 - Golgotha Prison

The name is not subtle, but the reference itself is actually oddly superficial. At the end of the dungeon, Ashley is separated briefly from the party and Lilka and Brad are captured and tied to crosses, evoking the characters Dismus and Gestas, the thieves crucified during the same execution as the biblical christ. There is little reference to that actual narrative however, instead seeming to draw from the fact that the name Golgotha is taken to be an epithet to mean literally “A Place of Skulls,” which seems rather appropriate and obvious for an execution field.

Bookending the start and end of this dungeon, we fight the boss monster, Trask. First in a scripted “loss” and then in a solo match with Ashley’s new dark henshin hero form, the “Grotesque Black Knight,” Knightblazer.

“Trask” is yet another transliteration* issue that comes from the juggling between languages. It actually comes from the Tarrasque, another monster most readily identified from its appearance in the original Dungeons & Dragons Monster Manual, itself originally taken from semi-obscure French myth of Saint Martha of Bethany and the Tarasque of Tarascon.

*(I realize I use this word a lot and it might not be as common use to others. A “translation” lifts meaning between languages; a “transliteration” is to lift written characters between them. Example: “Left” in English translates to 左[the direction] or 残[what remains] but transliterates to レフト. Inversely 左 and 残 both translate back to English as “Left” but transliterate as “hidari” and “zan” respectively; and レフト transliterates back into English as “refuto.”)

Surprisingly, the Wild Arms 2 design (which would also go on to persist as the core design throughout the rest of the Wild Arms series) is based more on the original myth than the D&D representations tend to be: While the end product looks nothing like the depictions of the Tarasque of myth, it retains the spiked turtle shell, the prominent dual horns, poisonous quality, and fins on its head here account for being “half fish.”

Also of note is that the title card identifies it as a “Dragonoid” and it has various metallic and machine-like features. These details are neat because it positions it as being not-quite a dragon, to work around a fact that will pop up much later: That dragons in Filgaia are extinct. And also to play into the fact that Dragons in Wild Arms are semi-mechanical lifeforms.

In any case, our scripted loss to Trask the first time around ends with the team knocked out and imprisoned in what appears to be a disused execution ground and associated holding cells. In our escape we run into monsters fitting the theme, who appear to be natural inhabitants, rather than guards put in place by the Odessa terrorist soldiers who are actually holding us here.

First up is the Wight, a classic undead warrior monster generally taken from D&D, but with a little more behind it than you might expect. The term Wight in English lore actually traces back quite far as an archaic term with little to no real association with monsters. The real intersection with name and subject comes from an early English translation of the Nordic Grettis Saga; In it the zombie-like creatures now better known as Draugr were referred to as apturgangr (lit.”againwalker”) but were translated as Barrow-wight. (lit.”[burial-]mound person”)

This may seem an odd choice, but the translation came at the hands of the eminent bookman William Morris. I say “bookman” because he was not just a prolific author of prose and poetry, but a pioneer of the revival of the British textile and printing industry. He and his wife, Jane Burden, did extensive arts, craft and design work in book and print design, book binding, and wall paper all stemming from the intricate design of modular and tiled printing blocks and stamps. Oh and he translated various works of epic poetry and myth into English, including old Roman epics, French knightly romances, and of course Norse sagas. (all of which he wrote and published what was basically fanfiction of, btw)

His seemingly erroneous “translation” of the Barrow-wight came as an attempt to reflect a comparable agedness to the name: Rather than translating from old Norse into modern English, he chose what he thought a suitable old English equivalent; “Barrow” referring to pre-christian Anglo-Saxon burial mounds, and “Wight” meaning “thing” or “creature” but often used disparagingly to refer to a person. The nuance there is actually quite clever, as the old Wight referred pretty exclusively to those living, even if it didn’t specify by definition, and that uncertainty or contradictory kind of implication uniquely fits a description of the undead.

This term would be picked up by J.R.R. Tolkein for use in Middle-Earth, retaining their lore and function from Norse legend to describe undead warriors. And from there you can follow the usual chain of influence to D&D, where the shortened term Wight really solidified itself as synonymous with the undead, and eventually down to Game of Thrones, where George R.R. Martin cleverly brings the whole thing back around to old risen bodies of northern warriors, not unlike the Draugr of Norse myth.

Anyway in Wild Arms 2 we get some sorta death yeti ¯\_(ツ)_/��

Next up is the Ghoul, which I think we all know is a pretty generic term in modern parlance, but it’s specific origins date back to pre-Islamic Arabia. It entered into English via translations of the original French translation of 1001 Arabian Nights, where it appears in one story as a monster lurking about the cemetery devouring corpses.

The Ghoul identity as a corpse eater quickly broadened into flesh eaters, and the association with lurking about graves in turn marked them as undead themselves until eventually the term became loosely applied to any variety of undead, including the thrall of vampires, supplanting the flesh of the dead with blood of the living and achieving a truly far removed meaning. Even in modern Arabic the term now broadly applies to any number of fantasy monsters.

And so long as we’re dabbling in pop culture transplants; the Arabaian word Ghul is in fact the same used in the name of the Batman villain, R’as al-Ghul, whose name/title has always been erroneously translated as “Head of The Demon.“

I have no idea why it’s a chicken with a mohawk but i love it

And finally the Bone Drake. I don’t know that this one actually has any real specific lineage...

“Drake” is generally a synonym for dragon, although there is some case of fantasy semantics where different settings will try to define distinct body types of dragons each with their own name, in which case Drakes are often either dragons which simply don’t exceed a certain size (generally no bigger than a non-magical animal such as a dog or a horse) or a wingless variation of whatever the setting’s prototypical dragon might be. I don’t know for certain, but I think this distinction in modern fantasy started with Tolkien’s wingless fire breathing dragon, Glaurung, and its offspring who were referred to as fire-drakes.

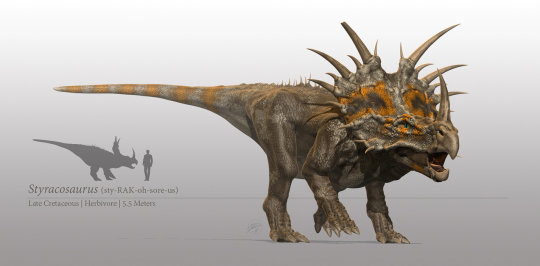

In any case, the specific term “Bone Drake” Doesn’t seem to appear with any visibility prior to Wild Arms 2, which leads me to believe it was just their name for a generic bone dragon-like creature. It does make for an interesting companion, aesthetically, to Trask being here, although there don’t seem to be any implications that Trask lives in this dungeon at all. Other than just being an obvious combination of cool fantasy things, it may also be pulled from Dungeon & Dragons’ Dracolich/Night Dragon; an undead (often skeletal) dragon raised from the dead, often by their own necromantic spells, hence the term “Lich.” For whatever reason they are oddly reminiscent of shield crested dinosaurs like the Triceratops or Styracosaurus.

The attack Rhodon Breath doesn’t tell me anything either. I think it’s just meant as “Rose Breath,” translating the “Rhodon” bit pretty literally, and references the smell of roses being present as a funeral, or else the palor of the faded pink color also called “Rose Breath.” There is some apocryphal reference to a Rhodon but of no significance that I can tell.

Clearly the theme here is death and the undead, and with some small stretch on part of the Wight, we could even say skulls all befitting Golgotha’s “Place of Skulls” epithet. It’s a really neat way to build this dungeon, albeit a little on the nose. But I really like the idea that the dungeon appears to be abandoned and now haunted by all these reanimated corpses and bones before the villains arrive to use it for their plans. Oddly there isn’t much of a martyrdom theme here, although we’ll get plenty of that a little later once we recruit our second magic user, summoner, christ figure, and perfect beautiful boy, Tim Rhymless to the team...

Anyway we get out, we fight Trask for real. Ashley turns into a saturday morning superhero. Trask gets solo’d. And we all just kinda move along without asking too many questions... Although the game dialogue describes this new form as a “grotesque black knight” the sprite work, 3D model, and even original character art don’t really convey much in the way of “grotesque” but in the context of the tokusatsu, henshin hero elements it’s not too hard to imagine that the design was meant to evoke a similar aesthetic to gruesome suit heroes like Guyver, Kamen Rider Shin, and Devilman. I do love the gill/tendon-like organic vent structure in the pauldrons that stay. And although it’s not visible in any of these images, but the D-Arts model has an exposed segment of vertebrae between the shoulders; that along with the teeth(?)/ribs on the open chest panels really helps bring out more of the “grotesque” quality of the design.

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Floods: Lost ...its structural integrity somewhere back there

Colin Thompson has been a great illustrator for children’s books, and occasionally a very neat author. But don’t let that cloud your judgement, because this novel is exactly as bad as it looks. The illustrations here certainly aren’t his best work, but lately they have been his only work, as his art style has morphed into this flat, computer-generated collage of photos and gritty rubber humans.

By the time it was over, this book put into me more than four instances of something in the narrative being overpowered, at least one pretty big continuity error, numerous typos, and even that thing the author sometimes does where he uses the wrong name to address a character. It also, of course, had the usual Belgian racism, because Colin Thompson still hates Belgian people for some reason.

If you’re not familiar with The Floods, it’s a gross children’s novel series about these morally dubious witches and wizards - a family - who do gross and sometimes epic shit, with very few reality-limitations put in place. I’ve been following it for quite some time.

Within the first two pages of the main story of Lost, Colin Thompson abruptly establishes that two of the main characters - and I’ll get back to you on how “main characters” is a weird concept in this series - got married and had a kid, who not only was very developed for a baby, but could literally talk in every word of the English language within a month of birth. Which is something that I expect by the next book to become another thing Colin Thompson completely forgets.

The book is about two women, Edna and Maldegard, keeping themselves occupied by traveling all over the country of Transylvania Waters and giving streets, towns, and mountains their own names. Because there weren’t any before. Which concerns me. I don’t recall the third-book-prequel having no names for anything, and I hope I just didn’t notice. In short, they’re mapping Transylvania Waters for the first time.

One thing I’m quite grateful for is that sometimes Colin Thomspon does designate things that The Floods are incapable of. The list is short, but the things that are on it really help. One of them is this thing in The Floods: Lost where Winchflat is super powerful at creating technology and can make a machine for anything, but there’s a really bizarre shack in the middle of a courtyard that he can’t penetrate or even use X-rays to look into. It’s one of the more Douglas Adamsian parts of CT’s bibliography. One time a paper booklet in a library told me that if you’re looking for more authors like Douglas Adams, try Eoin Colfer or Colin Thompson. The way I see it is more “Eoin Colfer is the poor man’s Douglas Adams, and Colin Thompson is the very poor man’s Eoin Colfer. Colin Thompson is also a very rich man’s surreal weirdo and therefore quite often worth it”.

Colin Thompson has a serious problem with “show, don’t tell”. I know that sounds crazy, because of how this is a book and “that’s how books work”, but I assure you that Colin Thompson still manages to abuse saying what happened instead of describing events like they’re actually happening. The last four Colin Thompson novels I read felt like almost the entire thing was a timelapse of seasons passing, and things end up being incredibly dialogue-driven.

100 pages of saying what happened later, interesting events in the story start to happen. There seem to be a number of villains in this sequel, and an asshole shapeshifter who’s in the form of a house, with a downright cannibalistic monster wife of his who he wants freed from prison, is the first one to make an appearance.

I don’t want to spoil how they take this man down, but it’s partly redundancies in writing and partly some pretty funny ideas that didn’t end up fully-fledged in my opinion. It sounds like a spoiler that I reveal he’s disguised as a house, but don’t worry, the book makes it incredibly obvious before telling the audience the reveal about four paragraphs later.

While that’s going on, there’s this subplot about how Mordonna and Nerlin, the parents, are trying to set up parliament in Transylvania Waters, to give the illusion to tourists that the country is a democracy or something. They live as kings and queens in a castle, and it’s not, but that will become clearer soon.

For some reason, CT goes ahead and chooses nerds as the acceptable target for narrator’s abuse, and the minor characters for the role of trying to set up a political party of the people.

Colin Thompson makes a pretty good point about how parliament sucks, especially when he says it’s because one party spends 3 or 6 years doing one thing, and then somebody else gets voted in and spends the same amount of time doing the opposite, but I don’t think the scene where Mordonna’s seven grotesque children suddenly walk in and get rollcalled just to form a bigger political party - The Royal Party - than the nerds’ one so that the nerds don’t get to have any say, sets a better precedent for the future. These characters? Well, the Floods are a pretty established large family, but they only used to get the spotlight. Nowadays, Colin Thompson always pushes his original main characters out of the spotlight, and other characters become “main” characters, purely as a freak accident. The book doesn’t give a single line to Valla or Merlinmary.

After the shapeshifter thing is resolved, the next villains are all Winchflat’s fault. Using a bunch of bones they found, this overpowered joke of a scientist character uses his cloning machines to bring fossilized creatures back from the extinction of time. Somehow, they are developed and aware enough to function in this new world quite quickly, not going into shock from the changes made to the world or having to relearn the alphabet.

First, Winchflat brings back an intelligent chicken, who starts a conversation with Winchflat. Of course this means Colin Thompson is gonna throw down that Ethel reference, because he sure loves his Chicken Named Ethel. He also brought back a whole bunch of regular chickens, oddly enough.

Basically, the chicken Ethel has delusions of grandeur and wants to be the rightful leader of everything in sight. This is a pretty funny prospect, but if the joke was handled right, it would still be spoiled by the overdose of characters-finding-it-funny-themselves-and-laughing. So I guess it wasn’t handled right then...

Naturally, the chicken gets totally dominated by The Floods, because of course it did. That’s how it works. Winchflat’s next mistake is to bring a four headed accountant - homo calculus - back to life, which actually ends up being a lot scarier than one would expect.

Good Stuff, Bad Stuff

This book isn’t perfect, but there’s at least one thing in there that considerably had an effect on me when I read it. I’ve already said a lot of bad stuff about this book. There is good stuff in it. I will tell you that thing.

As it turns out, that four-headed accountant from the pre-historic ages that Winchflat reanimated wasn’t just a joke about how “accountants suck” but actually something quite sinister, even bringing up a few dark implications about how the world used to be.

The creature’s name is Fiscal Matters, or just Fiscal. He has four bald heads, a cut moustache on each one, and pairs of glasses. Kinda looks like a caveman. His complusion is to count things, regardless of the value of what he’s counting. All homo calculus do that, and earlier on it’s said that many species went extinct because this behaviour bored them to death.

Winchflat talks to Fiscal for a bit, and then some pretty scary revelations happen. First, Fiscal thinks Winchflat is a servant to him, because apparently in the past, all witches and wizards were servants to his race. You can only wonder what kind of batshit insane forces were powerful enough to subdue the race that Winchflat comes from, but anyway...

Fiscal, second, wants Winchflat to open the strange room in the middle of the courtyard. You know, the weird one that Winchflat can’t open. Winchflat tells him about that, but then Fiscal says “I know how to open it.” So whatever’s in that crazy fucking shed, Fiscal knows what it is and wants to get in. It’s made worse by the fact that Fiscal Matters is getting increasingly aggressive with his “servant”.

The last one is that inside the weird room is a thing called The Ark of the Incontinent. The book never reveals exactly what it is, what it looks like, or how it got its name, but Fiscal wants to go in there so he can contact the rest of his species in outer space. They’re still alive and out there.

The resolution to this arc is pretty anticlimactic, but still unsettling. Basically, after Winchflat tells Fiscal to stay there and not open the door so he can walk away and consult his family, he gets back to find Fiscal counting stones on the shack. Counting how many stones are in the wall is the only way to access The Ark of the Incontinent, and Fiscal can’t, because the amount of stones changed over time and there’s no longer as many in the wall as there are supposed to be.

By the end of the book, Fiscal is still there. He’s still counting, and still hasn’t got into the shack. The Flood family just leaves him to his own devices, and feels perfectly secure about letting somebody with membership of an advanced, dangerous race keep trying to open the one doorway to contacting that race and unleashing war on the planet. Mordonna messes with Fiscal by changing the amount of stones in the walls randomly every now and then, but I think you can imagine how eventually that might turn out to be a bad idea. The probability involved sounds very dangerously high to me.

Lost

Guys... I don’t know. I have been reading this book series for a very long time, and wonder sometimes why I put so much effort into it. I always tell myself “this book will be the last one I read” but it never sticks. I guess I just still think there’s something in there that’s entertaining for me, and maybe there is. I don’t know if I want to continue reading until the very last book or not.

Bottom line is, it’s SBIG. SBIG at best, really. You read what I said up there, you know what’s wrong with it. And I think previous Floods books were better. But lately, as I finished reading this book, I’ve felt more interested in reading the next one. Colin Thompson finally gave continuity nods to things like The Knights Intolerant, which is a really big step forward for this series and means future books might have something I want to read. Read the book if you must, but I’ve been down the path of reading a sequel book before reading its pre-books. It doesn’t go well.

Your alternative is to read 9 big-text-novels until your quest to read the comedically-bad Lost pays off, but I think you have to be a pretty big Colin Thompson fanperson to want to do that. You either read one book in the middle and feel confused, or you read all of them in order and feel disappointed.

You know, fuck it. I’ve been told that books will set you free, and my eyesight and quota-for-consuming-fiction aren’t getting any better - I should just borrow the next book. I should borrow The Floods 11 and do something with my time that involves entering a weird and fantastical story. No more days of nothing but videogames, browser feeds and let’s plays...

#Colin Thompson#The Floods#The Floods Lost#talking about a book#full version of this post (in the notes) has amusing pictures from inside the book

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Slasher Fic

These days, when you hear "horror," the slasher is one of the first things that probably comes to mind. That's most likely because slasher films absolutely dominated during the 1980s, when many of us were growing up and forming our opinions about the world, and then made a strong resurgence in the 1990s when the younger half of a generation as doing the same thing.

There are a ton of slasher franchises that pop immediately to mind, each centering on an iconic killer: Michael Myers, Jason Voorhees, Freddy Krueger, Ghostface, etc.

But the slasher genre has, primarily, been confined to the silver screen. You just don't see as many novels in the same vein.

Oh, undoubtedly you find novels about serial killers -- but they tend to be police procedurals and cop thrillers, not the same classic "teenagers getting chopped into pieces" format as we're accustomed to in the movies. What's up with that?

Well. Some thoughts.

What is a Slasher Fic?

Slashers are stories about serial killers who go on murder sprees and wipe out a number of victims one-by-one, often all of them members of the same social group. The most traditional format involves a group of teenagers who are mowed down systematically by a killer while the authorities are useless to intervene. There is generally a moral element wherein the victims "deserve" to die for various on-screen transgressions, whether it's being Too Stupid To Live (tm) or having premarital sex (a classic, but now largely outdated, plot device).

You survive a serial killer, these narratives suggest, through moral superiority rather than force or skill.

And that makes sense, in a way, if you consider that these Hollywood serial killers are really not very much like real serial killers at all. They are the personification of our baser instincts, our animalistic nature: unstoppable killing machines that seem to feel nothing, either physically or emotionally, and whose desire for destruction is relentless. They are all of the worst parts of our nature, and so it makes sense that defeating them would require calling upon the best parts of our nature.

So Why Are There So Few Slasher Novels?

I suspect that part of the reason you don't see the book equivalent of Halloween very often is that, from a technical standpoint, many of the things we find most satisfying about slasher films do not translate very well to print.

The first issue is the violence. Slashers depend on gore and jump-scares; they live firmly in the "shock" camp. Which, as we know, is one of the hardest to write. Seeing someone killed in some particularly gruesome way affects the brain differently than imagining them being killed that way. You can still write the blood and gore, but it won't be quite the same. It's much easier to pull off over-the-top, campy, gleeful-dark-giggles-inducing fountains of blood on the screen than on the page, because you have absolute control over what it looks like. Your reader, on the other hand, will supply the details themselves with their own imaginations, which makes your job a little harder. Not impossible! But harder.

The second issue is narrative structure. Traditionally, novels are told from a single perspective, or at least a single perspective at any given time. Their strength is the ability to get into the head of a character and feel what they feel. Film, by contrast, provides a third party objective view, where the camera serves as a voyeur. That creates tension by putting us one step ahead of the victims at any given time.

In other words, it's a lot harder to shout "He's BEHIND YOU!" to characters in a book.

Therefore, a slasher novel would need to have a more distant omniscient narrator rather than a close-third or close-first person perspective.

But what about first person from the POV of the killer, I hear you asking, and to that I say: Excellent, it can be done, but what you get will not be a horror story in the classic sense. By putting is in the head of the killer, we will inevitably sympathize with him, which makes him not scary. He might be doing awful, grotesque things, but we won't be afraid of him because if we're in his head we know he's not standing right behind us.

To be afraid, we need to be in a position of sympathizing with the victim, and feeling what they're feeling. Otherwise, you're looking at a thriller or a crime novel or a mystery or anything else that's not horror.

(Which is fine, of course, but this is How to Write Horror and not How to Write Gory Thrillers, which would need to be a book of its own)

Okay, Okay, So Does That Mean I Can't Write a Slasher Novel?

Nope! This totally does not mean that.

But you just said....!

I know. I totally did. But just because something is difficult does not mean that it can't be done! There are quite a few young adult authors in particular who have written some classic played-straight slasher novels.

The trick to writing an effective slasher:

- Create a cast of characters who draw strongly on archetypes, but give them a little twist that makes them likable and unique. You want to do this because you'll have a large cast, by necessity (you need a lot of bodies to hit the floor), and you want those characters to be instantly relatable.

- Write from the perspective of your "final girl." You can deviate from this POV sometimes to provide a bit of drama (breaking away to see the killer in action elsewhere, for example) but most of your narrative space is going to be spent on watching the main character encounter the mutilated bodies of her friends and running from danger.

- Add an element of mystery. A slasher plot can feel a little thin. Bump up the cerebral horror by including a mentally engaging subplot or mystery to solve -- such as, perhaps, the killer's identity, or what he wants with the main character. You'll see this pop up time and again in most (but not all) slasher films: what seems to be a random attack turns out not to be so random after all, because the killer is actually deeply entwined in the Final Girl's life in some way. Unraveling that mystery puts some meat on the bones of the narrative.

And of course, remember to keep in mind the other tips and tricks we've discussed already in terms of building suspense, writing gore, handling shock, etc.

Some Required Reading to Get You Started:

I Know What You Did Last Summer by Lois Duncan (it's a child of its times, and has some really painful dialogue, but it's interesting to study alongside the film)

Some of R.L. Stine's Fear Street books are good. For our purposes, I'd recommend starting with Lights Out, The Prom Queen, and Silent Night. The Cheerleader series is pretty good too.

Some of Christopher Pike's novels are in the same vein. Try out Chain Letter, Slumber Party, and Weekend

Survive the Night by Danielle Vega is not strictly a slasher (the monster is an actual monster and not a serial killer) but the format is essentially the same, and it's worth studying.

The above are all young adult novels, because that's what happens when you're writing about teenagers getting carved up. Compare and contrast with these essential slasher-fic movies:

Nightmare on Elm Street

Halloween

Friday the 13th

Scream

Urban Legend

I'm probably missing some recommendations, so toss them in the comments!

81 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Uncanny Inhumans #19 Review

spoilers spoilers spoilers spoilers spoilers spoilers spoilers spoilers spoilers

The penultimate issue of Uncanny Inhumans and a continuation of the IvX tie-in from the creative team of Charles Soule, Ario Anindito, Kim Jacinto and Java Tartaglia (with another awesome cover from Fraizer Irving). Full recap and review following the jump.

There’s nothing good ol’ Maximus loves more than chaos. And with his fellow Inhumans embroiled in a war with The X-Men, Max has found the perfect opportunity to stir the pot and sew further mayhem. It’s not yet entirely clear what the mad prince has up his sleeve, but it’s certain to entail a good deal of hurt feelings and and property damage.

Utilizing Lineage’s powers to commune with the sentience of ancient Inhumans, Maximus has learned the secrets of engineering artificial Terrigen Crystals. It is the shortage of Terrigen, coupled with the fact that The Terrigen Cloud has proven poisonous to Mutants, that has led to the Inhuman/Mutant war. Maximus’ plot to create a new source of Terrigen may, in concept, bring about an end to the conflict… at least that is what he has told Triton in recruiting the banished Inhuman into his schemes. What exactly Maximus has in mind, his ulterior motives, however, remain to be seen.

The issue begins off the coast of Vietnam where the unlikely team of Max, Triton, Lineage and The Unspoken begin their venture to collect the various components and ingredients necessary for engineering Terrigen Crystals.

Maximus presents it all as some sort of heroic journey, yet the endeavor does not seem to have anything to do with heroism. Triton is there because he seeks redemption for his crimes; The Unspoken is seeking Terrigen because of the awesome powers it endows in him; Lineage is merely looking for the opportunity to stab Maximus in the back and seize power; and Maximus appears to be simply interested in it all for kicks.

Plunging far into the depths of the South China Sea, the team comes across a gapping maw on the seafloor that is actually a mouth leading to hidden kingdom of undersea creatures. Triton and the others have to fight off an army of these monstrous crustaceans as they proceed further on.

The Unspoken grows increasingly bemused by the situation. It’s not only that the affair has ruined his six thousand dollar Ferragamo loafers, but Maximus’ continued disrespect rankles The Unspoken as an effrontery to his status as royalty. He reminds Maximus that he had been the King of The Inhumans and demands that he be treated as such. Maximus is unmoved by the threat, yet acknowledges that he is quite aware that The Unspoken is indeed a king.

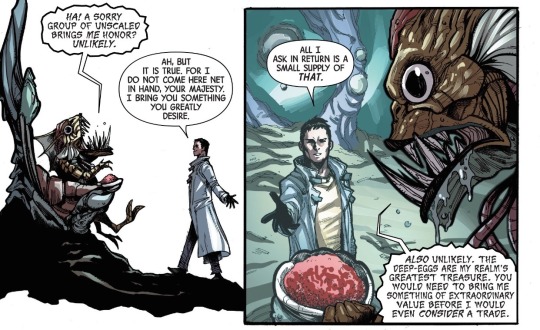

The team makes it further into this strange realm and eventually come across the court of the creatures’ queen. It turns out that the roe this queen produces, her eggs, are a key ingredient in creating Terrigen and Maximus has come to bargain for a cache of this roe.

The Queen (who oddly enough speaks English) is suspicious of Maximus’ intentions. What could he possibly have to offer that would incline her to trade away her precious roe? Well, it proves that Max does indeed have something she wants... something every queen needs, a king. Maximus offers The Unspoken, a true king, as the queen consort in exchange for the roe.

It’s not clear if Maximus is using his psychic powers for manipulation, but the queen accepts his offer. What is clear, however, is that Max very much has to use his powers to coerce The Unspoken to accept the bargain as well…

The Unspoken is left behind to a fate befitting his lousy character and the others leave with their prize in toe.

The ‘heroic journey’ continues on, taking them all over the globe as Maximus collects more of the rare components needed to create Terrigen. It turns out that a good third of these ingredients are unnecessary and Maximus has had the squad collect them simply to keep them guessing and maintain his being the only one who knows the recipe for Terrigen.

They end up in Mumbai, where Maximus procures the final ingredient. They are met there by Banyan, an Inhuman villain Maximus had reached out to in the previous issue. Max has instructed Banyan to make preparations, assemble some sort of machine that can be used to combine the ingredients they’ve collected and transfer it all into Terrigen.

Maximus asks Banyan for word of the Inhuman/X-Men War and Banyan replies that it has been waging on worse than ever. “Excellent,” Maximus says. “For you see, my friends, it is times of greatest adversity that gives rise to the greatest of heroes.”

He then goes on to add, “for example…” At which point the scene shifts back to the shores of the South China Sea where a large prawn-like monster arises from the depths and makes its way to land…

And it’s with this bizarre, unexpected and unexplained turn that the issue comes to an end with the promise of being concluded in the next (and final) installment of The Uncanny Inhumans.

Well, that was different… A fun albeit silly ride. And the silliness of it all leads me to believe this arc will not have a significant impact on the overarching storyline of IvX; that rather it’ll be self-contained and not a central element to the conclusion and resolution of the Inhuman/X-Men War. But that’s not to say it isn’t worth reading. Writer, Charles Soule, really excels at scripting Maximus; offering the character an irreverent and manic charm that is terrific fun to read. And there are a number of especially funny scenes… though it is Lineage who gets the best line of dialogue.

Laughs aside, I’m growing increasingly concerned over Triton’s fate as this chapter of the Inhumans mythos comes to an end. His quest for redemption has a strong tragic air to it, offering credence to the notion that he may be heading toward some sort of heroic, self-sacrifice in order to finally redeem himself.

I kind of hope this is the last we see of The Unspoken. He never clicked for me as a satisfactory villain for The Inhumans. The fate that befalls him in this issue, married off to the grotesque prawn queen, is rather befitting and I kind of hope this proves to be his ultimate fate (although I doubt it).

Really no idea what to make of the last scene. Has the Crustacea Kingdom sent some sort of monster to bedevil the land-living world? Is this related to the Monsters Unleashed event? Is it all a promotion for the restaurant chain, Red Lobster’s never-ending shrimp offer? Time will tell…

It’s mere speculation, but I wonder if the undercurrent of Maximus’ yammering on about the ‘hero’s journey’ is something of a commentary of how The Inhumans have ended up in this terrible conflict with The X-Men. The prevailing theory among many fans and readers is that The Inhumans have been tethered to the X-Men as a means to further propel The Inhumans into the spotlight. In truth, however, the event hasn’t done The Inhumans a whole lot of favors... it’s hard to not see them as the bad guys in IvX. I’m as big of a fan of The Inhumans as it gets and even I cannot really root for them it their victory would entail the demise of the entire Mutant race.

Maximus states, “times of greatest adversity that gives rise to the greatest of heroes,” and it seems as though there may be some meta-commentary to the line. Heroism in the face of adversity has been the guiding principle of the X-Men tales... and the stories has had to manufacture a near endless stream of backs-against-the-wall threats to keep this thematic moving forward. The Terrigen Cloud proving deadly to The Mutants was a retcon that kind of came out of nowhere. It offered up the latest in a long list of adversities needed maintain the X-Men’s constant thematic of being on the edge of extinction. And it’s kind of a pain in the ass because Uncanny Inhumans was trucking along just fine prior to getting tangled up in the whole ordeal of IvX. The cool stories and evolving plot-lines that Soule had been building all got sort of hijacked by this need to provide the X-Men with their latest extinction-level adversity.

The Inhumans will never be as popular as The X-Men. They are simply too weird to garner such a mainstream appeal. If there ever was a secret plot at Marvel to replace The X-Men with the Inhumans, the conspiracy has surely has been abandoned by now. The X-Men will get a whole new initiative following IvX... a large scale relaunch of their various titles that should put to rest the ridiculous notion that Marvel has been secretly trying to kill the X-franchise.

And The Inhumans will be getting a relaunch as well (albeit a considerably smaller one). Uncanny Inhumans will end and be replaced by The Royals. As sad as I am to see Uncanny Inhumans end, The Royals is looking like it’s going to be quite good. Furthermore, it appears as though the effort to make the Royal Inhumans into more standard-fare superheroes will be loosened and the squad will be allowed to re-embrace it’s more fitting science fiction roots.

As for the X-men, hopefully their ResurrXion titles will be good. And hopefully the franchise’s overarching thematic will evolve and innovate. The constant need of ‘great adversity so to give rise to great heroism’ has been overused and become stale. If not, then I feel sorry for the fans of the next group who gets caught up in the X-Men’s orbit... the next sacrificial lamb offered up to provide an extinction-level threat.

right... that went a little darker and more cantankerous than I had intended...

Anyways, the weird cliffhanger ending notwithstanding, Uncanny Inhumans #19 is a madcap romp and very fun read. The art by Ario Anindito, Kim Jacinto and Java Tartaglia is extremely well done.

Definitely recommended. Three out of Five Lockjaws.

#Inhumans#Uncanny Inhumans#IvX#Spoilers#Charles Soule#Ario Anindito#Kim Jacinto#Java Tartaglia#review

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Doctor Who Reviews by a Female Doctor, Season 6, p. 2

The Doctor’s Wife: “Bigger on the inside” has been a feature of the TARDIS since the show began, but in this gorgeous episode Neil Gaiman manages to make it look like the show’s creators invented the concept with this story in mind. A love story between a man and a time-space machine has plenty of potential to go awry, but it’s achingly beautiful here, and it brings out the very best in Smith’s Doctor.

I’m not especially enamored of the planet that the Doctor, Amy, and Rory land on, or of House as a villain, because disembodied voices don’t make for great antagonists even when they make cool special effects happen on the TARDIS. (I do like the name, though—it’s appropriate to have a villain named House in an episode that features an attack on the Doctor’s home.) While the eerie atmosphere is very nicely done, both on the planet itself and on the Ponds’ frightening dash through the TARDIS, when thinking back on this episode I mostly forget everything that isn’t centered on the Doctor and the TARDIS in human form.